Foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

History is the chronicle of famous men.

TECUMSEH

'Shooting Star'

Tecumseh watched the eagles

In summer o'er the plain

And heard them cry "if Freedom die,"

Ye shall have lived in vain.

For the charismatic Shawnee chieftain, Tecumseh, Shooting Star, was a fitting soubriquet. He flashed forth onto the northwest frontier pledging to protect Native traditions and territory for he knew once their land was lost, their freedom would follow. His opposition to the sale of land stemmed from his belief that no Native, regardless of the tribe, had a right to sell or give away land without the consent of all Aboriginals. Tecumseh was described by one writer as "the ideal of an Indian chief: stately and commanding, yet tense, lithe, observant and always ready to spring." Nevertheless, he walked with a limp resulting from a wound he received in a previous battle. Known as a skilled and fearless warrior Tecumseh was held in high esteem by friend and foe like.

|

|

Tecumseh {Painting by Benson John Lossing; no contemporary portrait of the great chief is known to exist.} |

Isaac Brock said of him

In His Own Words

"A more sagacious or more gallant warrior does not exist."

He was speaking of one of the continent's unforgettable sachems, perhaps the most lauded Aboriginal leader in North American history.

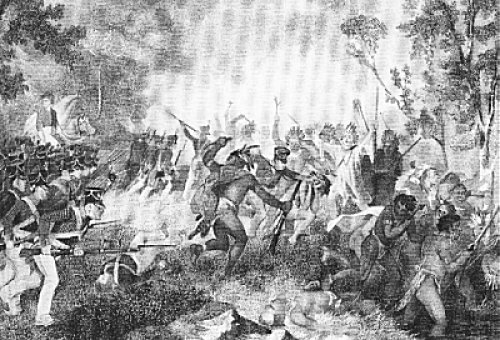

Tecumseh, "He Who Walks Over Water," was born at the Piqua village about five miles west of present-day Springfield, Ohio in 1768. A small hamlet called West Boston now occupies the site of Piqua. This was the ancient Piqua, the seat of the Piqua clan of the Shawnees, a name which signifies "a man formed out of the ashes." Tecumseh first battled as a brave in 1788 against Kentucky soldiers and grew to manhood during the chronic border fighting at the end of the eighteenth century. The young Shawnee scout was with the Aboriginal army led by Little Turtle and Blue Jacket that defeated an American force under Major General Arthur St. Clair in 1791. Said to be the best organized Aboriginal army ever assembled, the braves began their attack at dawn with the blended war cries of one thousand warriors. The battle ended three hours later with the complete destruction of St. Clair's forces. Tecumseh fought in numerous other frontier skirmishes with Americans, notably against General Anthony Wayne's army at Fallen Timbers where the tribes were soundly defeated.

|

|

Battle of Fallen Timbers |

Over time Tecumseh developed into an unmatched fearless fighter, a relentless but merciful foe. During a period of widespread violence and great brutality Tecumseh unfailingly brought into battle a rare humanity that never forgot the power of mercy.

"A daring, bold-looking fellow," Tecumseh was a man of intelligence, courage and character and quickly acquired a reputation as a stand-firm chief concerned more for people than for things. No portrait was ever made of the handsome, charismatic Tecumseh who was described by a British colonel as ,"being in appearance and noble bearing, one of the finest-looking men I have ever seen." He was five feet ten inches in height, but seemed taller because he walked proudly erect with a graceful, athletic stride. With skin the colour of light copper, he had an oval face and handsome and expressive features. He had a straight nose, a finely formed, expressive mouth and black, piercing eyes that gave him an exceptionally wild and impressive appearance. At a time when most Natives had adopted the clothing of whitemen, Tecumseh was a buckskin-clad, ostrich-plumed diplomat with an extraordinary gift of speech. He could speak English, but on public occasions he always used his native tongue. While silent of habit, when his anger was aroused he never failed to amaze American and British officials with his fiery, forceful fluency. "His eloquence was nervous, concise, impressive, figurative and sarcastic. Being of a taciturn habit of speech his words were few but always to the purpose."

Tecumseh had a great grasp of history and exhibited an astonishing knowledge of treaties that had been negotiated over the years. He knew details of hundreds of them and was able to cite chapter and verse to prove that most had been violated by white men. There was never a single voice raised to challenge his facts. Tecumseh's speeches, which could go on for hours, were described as a cascade of historical events passionately recounted along with sharp reasoning and soaring poetry. "We are made miserable by the white people who are never satisfied and are always encroaching on our land. They have driven us from the great salt water, forced us over the mountains and would shortly push us into the lakes. We are determined to go no further. The only way to stop this is for all red men to unite in claiming a common right in the soil. No one tribe has a right to sell even to one another much less to strangers who demand all and will take no less." After pausing Tecumseh cried out, "Sell a country! Why not sell the air, the clouds, the great sea as well as the earth? Did not the Great Spirit make them all for the use of his children?"

By the Royal Proclamation of 1763 Britain recognized Native land ownership. However, in the 1783 treaty that ended the American Revolution, Britain casually conceded the territory south of the Great Lakes to the United States, a cession that was uncalled for since the British and their Native allies had during the revolution won the frontier campaigns and controlled most of the region covered by the 1763 proclamation. It was feared by the British that when Aboriginals living in this territory learned they had been abandoned to the Americans who refused to recognize their ownership of the land, that they would avenge their loss by destroying the infant settlements of United Empire Loyalists along the north shores of the Great Lakes and the St.Lawrence River.

To forestall their outraged retribution Britain attempted to bring peace to the area by attempting to engineer an agreement between the tribes and the United States. In order to achieve this goal Britain violated the terms of the Treaty of Paris and retained control of the Western Posts all of which were located on American territory. This permitted Indian Department agents to maintain close contact with the Natives and attempt to ease tensions between them and American settlers relentlessly overrunning the west.

The Americans saw only duplicity in Britain's retention of the western posts, charging their reconciliation with the Aboriginals was simply an excuse to "supply them liberally with everything they stood in want of" including arms and ammunition. Americans suspected the British were not only arming but also instigating Native raids on American frontier settlements. Despite these sudden, savage depradations, the white enterlopers continued to flock to the fertile lands of the west and their continuing incursions served to solidity the ties of the tribes on the Upper Mississippi and Great Lakes with the British.

As beaded belts of wampum [*] conveying ceremonial messages of war were circulating from tibe to tribe the Americans correctly concluded that "A spirit is prevailing that is by no means pacific."

|

|

Wampum |

Native warriors were inspired by the Shawnee Lalawethika or The Prophet, Tecumseh's brother, who urged them to go back to their old customs and teachings, stop inter-tribal warfare and return to the clothing, implements, weapons and food of their ancestors. Tecumseh, perhaps the greatest orator of his time, hoped to form an Indian confederacy from Florida and Lake Erie and become its leader. "Where today are the Pequot, the Narraganset, the Mohican, the Pokanoket and many other once powerful tribes of our people? They have vanished before the avarice and oppression of the white man as snow before the summer sun." Then he asked the question: "Will we let ourselves be destroyed in our turn without a struggle, give up our homes, our country bequeathed to us by the Great Spirit, the graves of our dead and everything that is dear and sacred to us? I know you will cry with me, 'Never! Never!'"

As Tecumseh watched the land on which his people had lived for thousands of years traded away by a few tribes for trinkets, he assumed the role of a trans-tribal leader and undertook the creation of a pan-Indian alliance determined to stand together and resist the white onslaught. Rumours quickly spread about Tecumseh's determination to forge a 'pan-Indian confederacy,' a union fanned by the flames of anger and animosity felt by the Aboriginals towards the Americans. Tecumseh dedicated his life to defending the property of his people by preventing the sale of land by any tribe.

Tecumseh's nemesis was William Henry Harrison, general of the "17 Fires." whose skill as a negotiator was legendary. He engineered a series of land deals with various Native tribes by promising aid against their traditional enemies in exchange for land, then he promised competing tribes rights to the same land. His tactics were duplicitous but effective because in his view, the means justified the ends: ownership of what he called "one of the fairest portions of the globe." His thirteen treaties had secured no less than sixty million acres of what was probably then the richest land in the world. His best bargain was the Treaty of Fort Wayne involving the Delaware, Miami, Kickapoo and Potawatomi tribes and three million acres, bought for about one-third of a penny and acre. One tribe was conspicuously absent from this tribal giveaway: the Shawnee, whose principal chief, Tecumseh, had declared that Native lands were the common property of all Aboriginal peoples and no longer to be simply signed away by a mere tribal chief.

|

|

William Henry Harrison |

When Harrison heard of Tecumseh's declaration, he arranged a meeting with him. Through an interpreter he said to Tecumseh, "Your father requests you to sit by his side." "My father!" snorted a derisive Tecumseh, "The Great Spirit is my father! The earth is my mother and on her bosom I will recline." Legendary tales grow up around great men and their meetings, and one is told about this conference. Both men sat beside each other on a bench and as they talked, Tecumseh gradually edged closer to Harrison causing him to move away. Finally when he reached the edge of the bench Harrison protested. Tecumseh laughed and said, "Now you know how we Indians feel." It was reported that on another occasion when Harrison and Tecumseh met Tecumseh refused to join Harrison on the platform explaining, "The earth is the most proper place for the Indians." This meeting ended bitterly when Tecumseh and his followers stormed out after Harrison disputed that the Indians were one nation and owned the land in common. After all, said Harrison, "had not the Great Spirit given them different tongues?"

|

|

William Henry Harrison |

Worried Americans reported that "Indian prophets have been industriously employed attemting to seduce the Kickapoos, Saukeys, and other bands residing on the Mississippi and Illinois Rivers to war agains the frontiers of this country." Tecumseh travelled further afield to forge his confederacy. Following his meeting with Harrison, Tecumseh took to the road and eventually travelled from the Great Lakes to Tallahassee, Florida then west of the Mississippi River, one of his diplomatic missions covering 4,800 kilometres in six months. His message was always the same: tribes must unite, take up the cause and repel the expanding white presence. He met with varying degrees of success. On one occasion Tecumseh led a force of three thousand warriors into battle, the largest known mass of American Aboriginal fighting men ever assembled in one place.

In 1808 Tecumseh and his brother The Prophet founded a religious community called Prophetstown on the Wabash River where it joins the Tippecanoe River in Indiana, where Natives from the tribes of the Delawares, Whyandots, Ojibwas, Kickapoos and Ottawas came to live live together, insulated from the corrupting influence of 'white' America. Here they developed the concept of a permanent state, co-existing with but separate from the United States by a fixed boundary. Tecumseh hoped by demonstrating the unity and strength of their own culture, Aboriginal Americans could persuade the 'whites' to accept them as equals. It became clear that the United States was not prepared to do so and in 1809, Governor Harrison duped a number of chiefs into 'selling' three million acres in return for trade goods worth $7000 and an annuity of $1750. An enraged Tecumseh decided an alliance of Aboriginal tribes would have to halt the white flood by force.

Both Tecumseh and his brother, the Prophet Tenskwatawa, travelled among the tribes attempting to stir them up against the encroaching white man. "O Shawnee braves, O Potawatomi men, O Miami Panthers, O Ottawa foxes, O Miami lynxes, O Kickapoo beavers, O Winnebago wolves, lift up your hatchets, raise your knives, sight your rifles. Have no fears, your lives are charmed. Stand up to the foe. Fall upon him. Wound, rend, tear and flay his scalp and leave him to the wolves and buzzards." They listened spellbound to the compelling oratory of Tenskwatawa and Tecumtha.

Prior to leaving on his extraordinary journey to forge an Aboriginal alliance, Tecumseh cautioned his brother The Prophet not to confront the American military in his absence. Harrison, however, was growing increasingly alarmed by Tecumseh's success in uniting the tribes and decided it was time to advance against the Natives and destroy Tippecanoe, a plan he believed to be of great strategic importance. Harrison had been ordered by the president to maintain the peace, so he decided to camp his army of a thousand regulars and militia contemptuously close to Prophet's Town, hoping either to intimidate the Natives into submission or to provoke them into making the first hostile move. The Prophet, angered by the Americans' contemptuously close location to Prophetstown and ambitious to prove his leadership, decided to catch the Americans off guard by leading a surprise attack on Harrison and his forces camped overnight at Tippacanoe Creek. He assured his followers that because of his magic, the white men would be as harmless as sand and their bullets soft as rain. They then left on that rarity in Indian warfare, a night attack. In a fine rain at four in the morning on November 7, 1811, one of Harrison's sentries noticed something stirring in the darkness. He fired one shot before he was killed and the camp awakened by terrifying shouts and a fusilade of musketry tearing into the tents of the soldiers. The ferocious Battle of Tippecanoe had begun. Despite being surprised by the Aboriginal assault, Harrison and his soldiers kept their calm and held their line. As daybreak dawned, Harrison's forces at point of bayonet scattered the Natives warriors who were too demoralized even to return to their village.

|

|

Battle of Tippecanoe |

The disastrous defeat of the Natives resulted in the destruction of their settlement. The Americans entered Prophetstown, took what supplies they could carry then burned the town and started for home. Torched too was the Prophet's authority as a sachem and he drifted west and dropped into obscurity. Harrison's success was a powerful psychological victory for the Americans. President Madison deeply lamented the loss of so many lives by American forces whose "dauntless spirit and fortitude were victoriously displayed by every description of the troops and the firmness which distinguished their commander required the utmost exertions of valor and discipline." Subsequently, treaties were signed by the Americans and the Natives which resulted "in the extinguishment of their titles to the land."

Years later Americans looked back on the triumph at Tippecanoe as a great victory for Harrison the hero. He reminded voters in the presidential campaign of 1840 of his conquest and rode to victory on the slogan Tippecanoe and Tyler Too! John Tyler was Harrison's running mate. [See Below **]

|

|

William Henry Harrison |

The Americans continued to see Britain as the "instigator of the Indians,"and were convinced the West would be safe only when the British were driven out of Canada. In addition to this very real cause of concern, Madison informed the legislators of Britain's continuing harassment of American ships by "violating the American flag on the great hightway of nations and seizing and carrying off persons sailing under it." To eliminate these threats once and for all, Madison called on members of the legislature to assemble "sooner than a separation from your homes would otherwise be required in order to consider great and weighty matters claiming the consideration of Congress." The United States declared war on June 18th, 1812 and set out to capture Canada.

When Tecumseh returned to Tippecanoe, he found "great destruction and havoc - the fruits of our labour destroyed." The devastation of his home filled him with grief and rage. "I stood upon the ashes of my own home where my wigwam sent its fire up to the Great Spirit and there summoned the spirits of the braves" He vowed revenge and what better way to achieve it than join with the ranks of the redcoats in their war with the Long Knives. Tecumseh's dream of a permanent place for the Aboriginals marched with British imperial might, not because he supported Britain's policies but to use their cannons to further the cause of his own crusade: the prevention of the further flow of Americans into the Northwest.

Tecumseh first met Brock at Amherstburg, where Brock had gone with his force de frappe to confront Hull. Brock was in his office when the Shawnee chief entered and stood studying the British general. Brock was a big man, an impressive six feet three inches tall and obviously a person of some physical strength. Blond and blue-eyed, he wore a scarlet coat with white breeches, his long legs shod in shiny, black Hessian riding boots. His appearance was in sharp contrast to that of the copper-skinned Aborigine standing before him clad in buckskin with a lone eagle feather in his lustrous black hair.

|

|

Tecumseh & Brock |

Their meeting recalled the famous line from Rudyard Kipling's poem, The Ballad of East and West.

For there is neither East nor West

Nor border nor breed nor birth,

When two strong men stand face to face

Though they come from the ends of the earth.

The blond British general and the dark-skinned prince of the wilderness became as brothers. Brock's decision to attack Fort Detroit despite opposition from his officers was a bold one. Tecumseh was impressed and exclaimed in delight, "This is a man." The following day Brock addressed his troops and the thousand Natives of various tribes. He had come across the great salt lake (Atlantic Ocean) at the request of their great father to help them, and with their assistance he would drive the Americans from Fort Detroit. Tecumseh responded that they were steadfast in their friendship and were ready now to shed their last drop of blood in their great father's service. Seeing Tecumseh surrounded by his fiery and indomitable warriors, all united by his leadership alone, Brock realized the powerful personality of his new and very valuable ally.

Hull yielded not to the strength of the British forces, but to his perception of their strength. The war of liberation Hull had launched became a comedy of errors and in the presence of Brock's redcoats and the Aboriginal braves whose wild war-cry would soon strike terror in the heart of Hull, he folded. Tecumseh's warriors contributed greatly to Hull's fears of the force he faced, and Brock played on this fear in his masterful message to the American commander in which Brock said that while he did not propose to "join in a war of extermination," the Natives might very well be "beyond control the moment the contest commences." Brock's daring decision to confront the powerful force and fort resulted in an amazing victory, and both before and subsequent the surrender, the Natives' conduct was beyond reproach.

During the winter of 1812-13 Tecumseh and some 1200 warriors joined forces with 900 regulars and militia under the recently promoted haughty, hefty, red-faced Brigadier General Henry Procter. Their assaults on two American forts proved unsuccessful and by the end of July morale among them flagged as a result of the heavy casualties they had suffered. The situation on the Detroit frontier worsened with the defeat of a British fleet at the Battle of Put-in-Bay on Lake Erie in September. The Natives marvelled at the roar of the guns and watched intently as the heavy smoke of battle drifted over the lake.When the thunder of the cannons had ceased and the smoke that obscurred the sky had cleared they eagerly asked who had won. Fearing the warriors might leave if they learned of the British defeat, Procter said the British vessels had beaten the Americans. He knew the worst had happened for his life-line with Niagara was cut. Lacking supplies and fearing an attack at any time by Harrison, Procter's forces at Detroit prepared to withdraw. As they set fire to the fort and threw broken guns, cannon balls and garbage into the well, Tecumseh looked on with alarm.

|

|

Henry Procter |

Despite Tecumseh's pleas to stand and fight, Procter was determined to retreat. Tecumseh,infuriated at Procter's seeming fear of fighting delivered with fiercesome glare his last powerful speech.

In His Own Words

Father, listen to your children. You have them now all before you. You always told us you would not draw your foot off British ground, but now you are drawing back and we are sorry to see our father doing so without seeing the enemy. We must compare our father's conduct to a fat dog that carries its tail on its back, but when fearful drops it between its legs and runs off. You have the arms and ammunition our great father sent for his red children. If you intend to retreat give them to us and you may go and welcome. Our lives are in the hands of the Great Spirit. We are determined to defend our lands and if it is His will, we wish to leave our bones upon them."

|

|

Tecumseh & Procter |

Procter did not share Tecumseh's fervor to fight nor his pledge to abandon his bones on hallowed Native ground, but he was fearful of risking a rupture with the Aboriginals. Despite this real concern Procter believed retreat was in their best interest and he prepared to do so. His plan was to withdraw up the Thames valley and in so doing extend Harrison's lines of communication and keep his own forces well away from Lake Erie. What the British could not carry they burned. When stores and equipment were loaded on every craft that would float, the ships set sail across Lake St. Clair for the River Thanes. Procter retreated overland in a cart up the valley of the Thames towards Lake Ontario. An angry and disgusted Tecumseh followed the fleeing British forces.

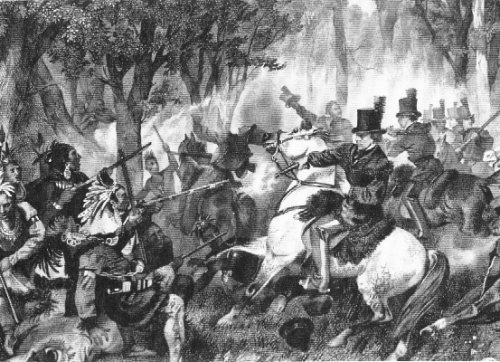

On the 5th October 1813, the pursuing American army caught up with Procter at present day Thamesville. While awaiting the start of the shooting, Tecumseh talked with a few of his chief warriors. One asked, "Father, what are we to do? Shall we fight the Americans?" Tecumseh replied,"Yes, my son, We will be in their smoke before sunset. My body will remain on the field of battle." He then set aside his anger and despair and for the last time shook Procter's hand, saying simply, "Father, have a big heart." Even as bugle blasts rang through the forest announcing the coming of the American cavalry, Tecumseh was moving among his men to motivate and sustain. Dressed in deer skin and wearing a handkerchief fashioned into a turban in which was placed a fine white ostrich feather, he could be seen shaking hands with each British officer as he passed. "He made some remark in Shawnee," one of them remembered, "which was sufficiently understood by the expressive signs accompanying his comment and then passed away forever from our view."

Harrison's horsemen charged the thin red lines at a gallop, and the shock of the mounted menon the tired and hungry soldiers was swift and overwhelming. They breeched the British ranks, cutting down all opposition with sabres and trampling men under foot.

|

|

Cut by the Cavalry |

Once through the red ranks, they turned about and the redcoats found themselves fired on from both sides. It was all over in a few minutes. Demoralized by hunger, fatigue and lack of supplies, the British broke and ran. General Procter, whose leadership was less than inspired, decided to quit the field of battle. Mounting an excellent charger and accompanied by his personal staff, Procter sought safety in flight to the east.

As Tecumseh and some five hundred braves prepared to face their fate at the hands of 3000 Americans, all eyes followed the familiar figure in his tanned buckskin. In his belt was his silver-mounted tomahawk and his knife in its leather case. About his head a handkerchief rolled like a turban in which was a white feather. The Natives had lain silent until Colonel Johnson's cavalry had advanced to within range. Then Tecumseh's loud war-cry rang out the signal for battle. Above the clamour of the frenzied hand-to-hand combat, Tecumseh roared out his challenge. A few saw him, blood on his face, defending his heroic but hopeless vision to the last. Tecumseh's keen eye singled out the leader and he rushed to strike him down, his tomahawk gleaming above his head. Before he could send it on its deadly flight, there was a flash and a bang. The colonel fired the fatal shot. Tecumseh's tomahawk dropped harmlessly to the ground and in the forty-fourth year of his life, the noblest of the red warriors fell dead on the spot. Stilled was the war cry and silver eloquence that had urged his followers to fight. Tecumseh was no more.

|

|

Death of Tecumseh |

No funeral oration was uttered over his grave. No totem marks his resting place. To this day no one knows what his followers did with his body. The red man's secret was jealously guarded. With the death of Tecumseh, the last hope of Native unity in the West vanished and effective Aboriginal resistance south of the lakes ceased. Of Tecumseh's confederacy nothing remained. His arch-rival, Harrison, described his fallen foe as "one of those uncommon geniuses which spring up occasionally to produce revolutions." The revolution of the tragic hero "ever merciful and magnanimous" had been crushed. "His loyalty was not to Canada nor to the British in Canada, but to a dream of a pan-Indian movement that would secure for his people the land necessary for them to continue their way of life."

Gloom, silence and solitude rest on the spot

Where the hopes of the red men perished.

But the fame of the hero who fell shall not

By the virtuous, cease to be cherished.

|

|

Inauguration of Harrison |

[*]Wampum the part-mystical, part-monetary strings of beads recognized as a medium of trade and diplomacy by Native Americans.

[**]Harrison's satisfaction was short-lived. At his inauguration in Washington on March 4, 1841, President William Henry Harrison declined the offer of a closed carriage and rode on horseback to the Capitol, braving cold temperatures. After speaking for more than an hour, one of the longest inauguration speeches in U.S. history, he rode back to the White House, catching a chill that eventually turned to pneumonia. He died on April 4th, 1841, one month after taking office, the first president to die in office. Tyler finished his term.Copyright © 2010 W. R. Wilson