Foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

SHEAFFE & QUEENSTON HEIGHTS

History is a pattern of timeless moments.

In his History of the English Speaking Peoples, Winston Churchill referred to Brock as "the ablest British commander" of the War of 1812. In August of 1943 when he took a break from his meeting in Quebec with Mackenzie King and Delano Roosevelt, Churchill visited Queenston Heights where he viewed the site of Brock's great success. He was familiar with the details of the war and talked about the assault on the Heights and its heroes. On examining the hill and the circumstances under which the Hero of Upper Canada died, Churchill described Brock's precipitate attack on the Americans atop the Heights as an "impulsive dash up the slope."

|

|

Young Winston & Old Winston Churchill |

As he gazed upon the magnificent monument to Brock, Churchill inquired where the memorial was to the real victor of the battle, Major-General Roger Hale Sheaffe. When told there wasn't one, Churchill mused, "Perhaps because he wasn't killed." Whether dead or alive Sheaffe in the minds of most Upper Canadians never merited a monument.

In the 1760's Roger Hale was the King's representative Collector of Taxation in Boston Massachusetts and his deputy was a William Sheaffe. William's admiration for his superior was such that in 1763 he named his seventh child Roger Hale, the first Roger Sheaffe. During the War of Independence, Lord Percy, the leader of the British forces in Boston, resided in the boarding house owned by Susanna Sheaffe, the widow of the recently deceased William. Lord Percy was so struck by the qualities and the leadership potential of young Roger, that he funded his education in a military academy in the United Kingdom. Lord Percy became a life-long friend and benefactor of young Roger, purchasing his many regimental commissions.

Sheaffe began his military career as an ensign and advanced to lieutenant in the 5th of Foot. The regiment was stationed in Ireland from 1781 until 1787 when it was sent to Canada. Sheaffe served at Detroit and at Fort Niagara under Lieutenant Governor John Graves Simcoe who considered him a "Gentleman of great discretion incapable of any intemperate or uncivil conduct."

|

|

Roger Hale Sheaffe |

In 1802 Sheaffe came to Canada with the 49th Regiment as a lieutenant colonel. By 1811 as major general he was ordered by Prevost to assist Brock at Niagara. The two men appear to have had little in common. Brock did not share Simcoe's whole-hearted admiration for Sheaffe. In a letter home Brock commented, "General Sheaffe has lately been sent to me. There never was an individual so miserably off for the necessary assistance." While he did not elaborate on this remark it is believed Brock was referring to Sheaffe's lack of leadership capabilities. The near-mutiny at Fort George while Sheaffe was in commanded confirmed Brock's assessment because it was attributed by the men who initiated it to Sheaffe's "extreme rigour."

In his assessment of Sheaffe's competence as an officer, Brock acknowledged that "no man understands the duties of his profession better" and stated that Sheaffe had "shewn great zeal, judgement and capacity." Nevertheless, Brock found him to possess "little knowledge of mankind." His martinet behaviour combined with his"rude manner of speaking and disagreeable way" with the troops led in many instances to his being inconsiderate and injudicious.

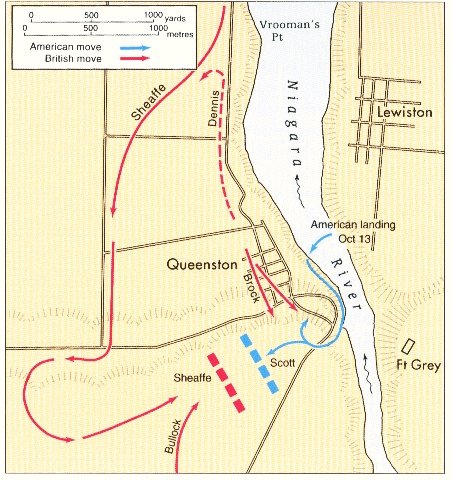

The Americans chose to initiate the assault on the Niagara peninsula from Lewiston to Queenston. At the point of their attack the river is about 250 yards wide. The current is strong at that location but a skillful boatman could make the crossing in about fifteen minutes. Plans called for thirty boats each carrying 20 ment to make the crossing, but only twelve were actually available to ferry the force of some four thousand across the river.

|

|

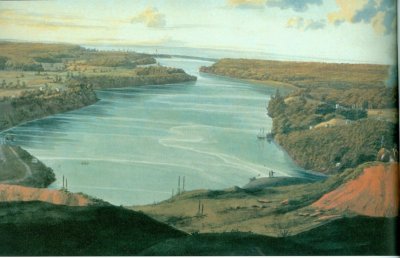

View of Niagara [1812 No. 1] |

This view of the Niagara River is from Queenston Heights looking north to Lake Ontario. The village of Queenston is below the heights to the left. Lewiston, New York, is on the right. In October 1812 American assault craft departed from the American shoreline located almost directly below where to British infanrtymen are sitting on the right.

|

|

American Invasion at Queenston failed when reinforcements refused to cross the Niagara River. [U.S. National Archives] |

Twelve boats loaded largely with recently recruited regulars started across the two hundred & fifty yards of the forebidding Niagara River in the early hours of the morning of October 13, 1812. It was dark and fierce winds lashed the huddled men with a driving rain. Some two hundred were able to make shore before they were noted by a Canadian sentry who raised the alarm. Two companies of the 49th Regiment and detachments of the militia from York and Lincoln counties - about three hundred in all - commenced firing at the landing party while artillery opened up on the boats still crossing the river. The rapid fire put the American leader, Colonel Solomon Van Rensselaer and "fifty or more Americans out of action." Lewiston batteries comprising 24 cannons opened up and they were answered by the single British gun on the heights and the big cannon at Vrooman's Point a mile down stream.

Brock had retired in his uniform in the early morning hours after dispatching orders to the district militia to prepare to meet the crisis he knew was coming. Around half-past three he was awakened by the distant rumble of cannon fire from the direction of Queenston. He suspected it was a feint for he fully expected the main assault would be at Fort George. He ordered Major General Roger Hale Sheaffe, his second-in-command, to begin bombarding the the Americans at Fort Niagara and to be prepared to depart for Queenston when called.

Brock then sprang to the saddle and galloped away to the Heights. Greeted on his arrival by a hearty cheer from the men of his own old regiment, the light and grenadier companies of the 49th, Brock spurred forward straight up the slope to the single eighteen-pounder on the edge of the terrace overlooking the river. He dismounted and looked below where American boats were crossing. Noting the premature bursting of a shell from the eighteen-pounder he ordered the use of a longer fuse. As he did so he heard hollering from the heights above and turned in time to see American troops advancing straight for the battery. Quickly spiking the cannon the detachment and Brock hurriedly led their horses down the slope into Queenston.

After dispatching word to Sheaffe to hasten to the heights with half the garrison troops and the flying artillery, Brock with a detachment of the 49th threw caution to the winds and charged up the hill to retake the captured cannon. He died there on the slope his sublime leadership lost on a fire-fight.

|

|

Fanciful Depiction of Brock at the Battle of Queenston Heights |

Sheaffe's reinforcements comprising some 380 men of the 41st Regiment, two companies totalling 300 of the York Militia and a number of Native warriors approached along Concession Road No. 2 a little used back trail to Queenston. They arrived at Vrooman's Point around 11 a.m. where Sheaffe found a handful of troops and heartsick news. Brock was dead and Americans were entrenched on the Heights.

Unlike Brock Sheaffe decided not to chance a charge up the wet, muddy hill, considering it suicidal in the face of a force of well-trained defenders. Instead he swung his column west where they trekked through field and forest behind Queenston towards the village of St. David's. It was a circuitous route but by ascending the heights using a narrow path two miles west of Queenston, Sheaffe was able to gain access to the high ground unopposed. As soon as his men reached the crest of the escarpment Sheaffe led them eastward. When they reached a field adjoining the road that led to Niagara Falls they were joined by fresh forces from Fort Chippawa including a grenadier company of the 41st Regiment under Captain Bullock.

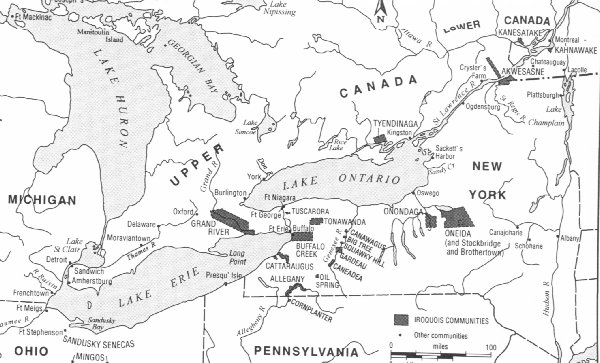

Accompanying Bullock's forces were some 150 Mohawk warrors led by Chiefs John Norton and John Brant, son of Joseph Brant, the gallant Mohawk chieftain who had died at the age of sixty-five on November 24, 1807. The combined British and Aboriginal forces numbered 1000 rank and file half being regular troops. Chief Norton proved to be one of the best friends the British had in the Grand River settlement whose residents were divided over whether or not they should be free to sell their land. Some opposed this wanting instead to maintain their traditional way of life without large numbers of whites living among them. This group, which was strongly encouraged by Iroquois still residing in the United States, chose to remain neutral. Shortly after British military successes at Mackinac and Detroit some three hundred of the Grand's four hundred warriors took to the field in support of the redcoats. Most of these Natives wanted outright ownership of their with freedom to sell it to the highest bidder if they chose. Led by Norton they supported the British from the beginning of the conflict.

|

|

John Norton |

|

|

Iroquois World in 1812 |

Norton had met Brock on 6 September 1812 at Fort George and following his briefing he sent word to the Grand River for the rest of the chiefs and warriors to assemble at the fort with all possible speed because Brock thought the American attack was imminent. Prior to going to war the warrior ritual required them to demonstrate their decision to take up the tomahawk and join the British. The chief stuck his hatchet in a war pole and the warriors, dressed and painted for battle formed around, each man giving the chief a piece of wood painted red as a symbol of his committment to the coming battle. Songs were sung, war drums beaten and the war dance followed. The dance was physically and emotionally draining. An observer said that during the dance Norton's "whole appearance was instantly changed," his normally mild and humane demeanour taking on "a most savage and terrific look."

The real Battle of Queenston Heights began at 3 o'clock on the afternoon of Wednesday, October 13th, 1812. General Sheaffe had gained access to the heights unseen by the Americans who were astounded and taken completely by surprise at the sudden appearance of the red wave of British and Canadian soldiers with bayonets gleaming in the bright October sunlight. All the while the wail of whooping warriors painted black and red added to their panic. If the war paint failed to serve its purpose and petrify the soldiers, they were frozen by the horrible howls and shrieks the wailing warriors made when they attacked. The savage sound that deafened the ear and horrified the heart frequently made even the bravest drop his weapon and flee. Soldiers heard no orders, felt no shame and retained no sensibility but the dread of a terrible death. Many were shattered forever by the shock of contact and conflict with Native warriors.

|

|

Battle of Queenston Heights |

A party of Aboriginal warriors under John Brant skirmished ahead, harassing and impeding with hit and run raids any American attempt to consolidate their defences, their frenzied, fearsome, battle cries demoralizing the tired and terrified invaders and causing one to comment after that he "thought hell had broken loose and let her dogs of war upon us." He expected at any moment to become "a cold Yankee" as the soldiers said. The terrifying war whoop of the Indians echoed far and wide and American militiamen across the river could not be prevailed upon to come to the support of their regulars.

Slowly and deliberately Sheaffe positioned his troops in an extended line of advance, deploying them on three sides of the American position. The main body on the right was composed of troops of the 41st Regiment, and flank companies of the Niagara militia. They had two 3-pounder field pieces which they had dragged up the hill. The left flank included the Light company of the 41st Regiment under Adjutant McIntyre, supported by militiamen, Mohawk braves and a company of African-Canadian soldiers under Captain Runchey. The Light Company of the 49th along with men of the York and Lincoln militia formed the centre.

Contact with the American invaders occurred around 4 p.m. The first to meet them were Indian attackers whose ferocity quickly routed the riflemen causing one to comment after that he "thought hell had broken loose and let her dogs of war upon us." He expected at any moment to become "a cold Yankee" as the soldiers said. The terrifying war whoop of the Indians echoed far and wide and American militiamen across the river could not be prevailed upon to come to the support of their regulars.

The Americans were stranded on the Heights with their backs to the river, the Queenston defenders on their right and Norton's warriors and Sheaffe's forces fast approaching from the front. A fire fight ensued and "small arms were discharged, the whizzing of balls and the yells from all quarters exceeded description." Sheaffe's whole line fired a single musket volley, then "infuriated at the loss of their beloved general," the troops fixed bayonets and charged at the invaders poised on the precipice of the river bank. As the Native warriors closed in on the left flank, guns at Vrooman's Point pounded the enemy's right flank. Stunned to extra ferocity by one fierce desire that steeled every heart. Sheaffe's men with blows and bloodshed jabbed and stabbed in savage rage.

Panic seized some of the American soldiers who turned and broke for the brink of the cliff, flinging themselves in their fear over the edge and tumbling to the rocks below. Others scrambled down the steep sides frantically fighting their fall by clutching at bushes and brambles lining the banks. Those who made it down began to swim across, but they were harried by sharpshooters taking pot shots at them with good effect. Others tossed down their arms and sought to surrender, while Indians rushed about finishing off any unfortunates.

The sights and sounds of battle and returning wounded soldiers dampened the ardour of the American militiamen waiting on the other side, who earlier had been eager to launch the conquest of Canada. Their reaction to the fierce fighting and its bloody effects resulted in their refusal to move to the waiting boats."Neither reason, order, persuasion nor shame had any effect." They would not leave Lewiston. It amounted to mutiny, but they defended their lack of courage by saying they had not enlisted to serve outside New York.

Meanwhile the battle raged on the Heights, the besieged attackers cut up and captured. After the short, sharp engagement, the American commander, Winfield Scott, waved a white cloth on a sword point to surrender. He decided the fight was finished. Finally the bugle sounded and peace reigned over riot. Under a flag of truce, some 950 officers and privates surrendered unconditionally. By 4:00 p.m. the battle was over. American casualties numbered 90 killed, 100 wounded; British losses totalled 16 killed, 69 wounded. The incalculable worth of the Aboriginal warriors had ensured a victory.

The American President James Madison, who decried another American defeat at the hands of smaller British forces, attempted to consol himself by indicating quite correctly that Brock's loss had made the British victory a pyrrhic one.

In His Own Words"Our loss has been considerable and is deeply to be lamented. That of the enemy will be more felt, as it includes among the killed the commanding general, who was also the governor of the Province."

Later the American militia were parolled, but the regulars were rounded up and sent to Quebec, a most unpleasant experience as Scott later recalled.

A militia officer described Sheaffe's conduct throughout the contest as "cool though determined and vigorous." Using a masterful manoeuvre Sheaffe had routed the invaders and captured nearly 1000 of their number with insignificant British losses. Sheaffe's satisfaction at his success was short-lived, for while he won the battle, he lost the advantage. To the consternation of his colleagues, Sheaffe agreed to a cease-fire just when his victory had made the Americans vulnerable. His detractors charged that Brock would have harried the Americans home, captured Fort Niagara and carried the war to America's heartland.

Sheaffe was always eclipsed by Brock and his victory at Queenston is the supreme example of this. Brock's name and fame are forever associated with the battle which Sheaffe won with sound, highly intelligent tactics. Sheaffe failed to exemplify the truism that great men are not made by propaganda, but grow out of their actions. Exultation at Sheaffe's impressive victory was muted by the melancholy mood that pervaded the province at the loss of its beloved leader. It is said that history has accoustical deadspots, places where the whole tune can't be heard. Surely this is one of those places, for instead of heralding the hero of this victory, reporters bemoaned Brock's death. They referred to the spot where he fell as, "classic ground" and to his name as >"imperishable." Brock's demise "stifled celebration." The "easily won victory" was paltry payment for the premature death of their Chief who died "in the pride of manhood and noon-tide of his career." Brock's simple patriotism was infectious and his ability, eagerness and energy commanded respect - even from his enemies.

Instead of grateful thanks, there was widespread grieving throughout both provinces. The Heights of Queenston had been "rendered more memorable"by Brock's death than by by Sheaffe's success. Canadians would gladly have "foregone the triumph," if they could have restored him to their midst. Sheaffe's fine victory was lost in the veil of tears shed by a sincerely saddened public. The massive mourning that took place at Brock's death exemplified the fact that a great leader's charismatic power is not mere phantasm. The qualities associated with decency, kindness, sensitivity, compassion, honesty and empathy are impressive resources.

"Joy's bursting shout in overwhelming grief was drowned,

The sounds of triumph died on every tongue."

For many years the only marker that mentioned Sheaffe's name in the extended area of Queenston was a small stone located a mile and a half west of Queenston on the south side of York Road where the British troops led by Sheaffe ascended the Heights and then moved eastward to confront the Americans. The stone marker says simply:

"Sheaffe's Path to Victory

October 13th, 1812"

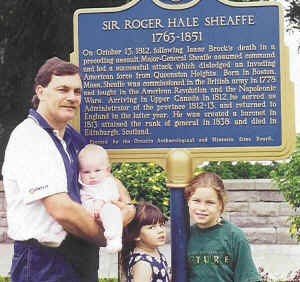

Time has modified this omission. Just inside the entrance to Queenston Heights Restaurant there is an impressive bronze sculpture of a mounted Major General Roger Hale Sheaffe, 1763-1851. Outside nearby a bronze plaque dedicated to Sheaffe's victory was erected by the Ontario Archeological and Historic Sites Board in 1959. Predictably Sheaffe's provincial plaque stands in the shadow of Brock's magnificent monument.

|

|

Roger Hale Sheaffe Provincial Plaque |

"Sir Roger Hale Sheaffe

1763-1851

On October 13, 1812 following Isaac Brock's death in a fool-hardy hop up the Heights, Major-General Sheaffe assumed command. Wisely deciding not to follow in the footsteps of his superior, he led a successful counter-attack, which dislodged the invading force from Queenston Heights.

Few mortals could measure up to Brock's reputation among soldiers and civilians alike and Sheaffe was never in the running. He was found wanting in whatever he did. Happiness over his triumph on the Heights of Queenston was greatly dampened by the death of Brock, whose loss to the many who loved him almost outweighed the worth of the victory. When the Americans invaded York and Sheaffe made what military men argue was a reasonable tactical decision to fall back to fight another day, he was widely criticized and charged with failing to utilize fully the forces at his command. In so doing they said he exposed the province's capital to capture. Regularly declining to take risks, Sheaffe's military manner reflected his cautious personality. To the local population of York, his decision to fall back to Kingston was akin to cowardice. He lost all credence in the colony and subsequently was ordered to take up a command in Quebec. Even there he was criticized for "indifferent service," and was recalled to England.

Born in Boston Mass. Sheaffe was commissioned in the British army in 1778 and fought in the American revolution and the Napoleonic wars. Arriving in Upper Canada in 1812 he served as administrator of the province 1812-13 and returned to England in the latter year. While Canadians had reservations about Sheaffe's military capability, the British government saw merit in the man and recognized his service in Canada. He was created a baronet in 1813, an honour higher than that accorded Brock. Brock's knighthood died with its recipient; Sheaffe's baronet was hereditary and passed on to the eldest son. Roger Hale Sheaffe was raised to the rank of lieutenant general in 1821 and to general in 1838. He died in 1851 at his home at 36 Melville Street in Edinburgh, Scotland having outlived most of his contemporaries.

The war which began with much gusto and gloating had been nothing but a bust for the Americans. At the end of 1812 after six months of war, their achievements on land were nonexistent. A few American soldiers occupied Canadian soil, but as prisoners. Attempts to invade had backfired, resulting in the loss of Detroit and Mackinac and a resounding defeat at Queenston. Winter descended and froze any further attempts at invasion. The new year that brought naval and military reinforcements from Britain would augur ill for any improvement in the American position, unless leaders and a more committed military were forthcoming.

|

|

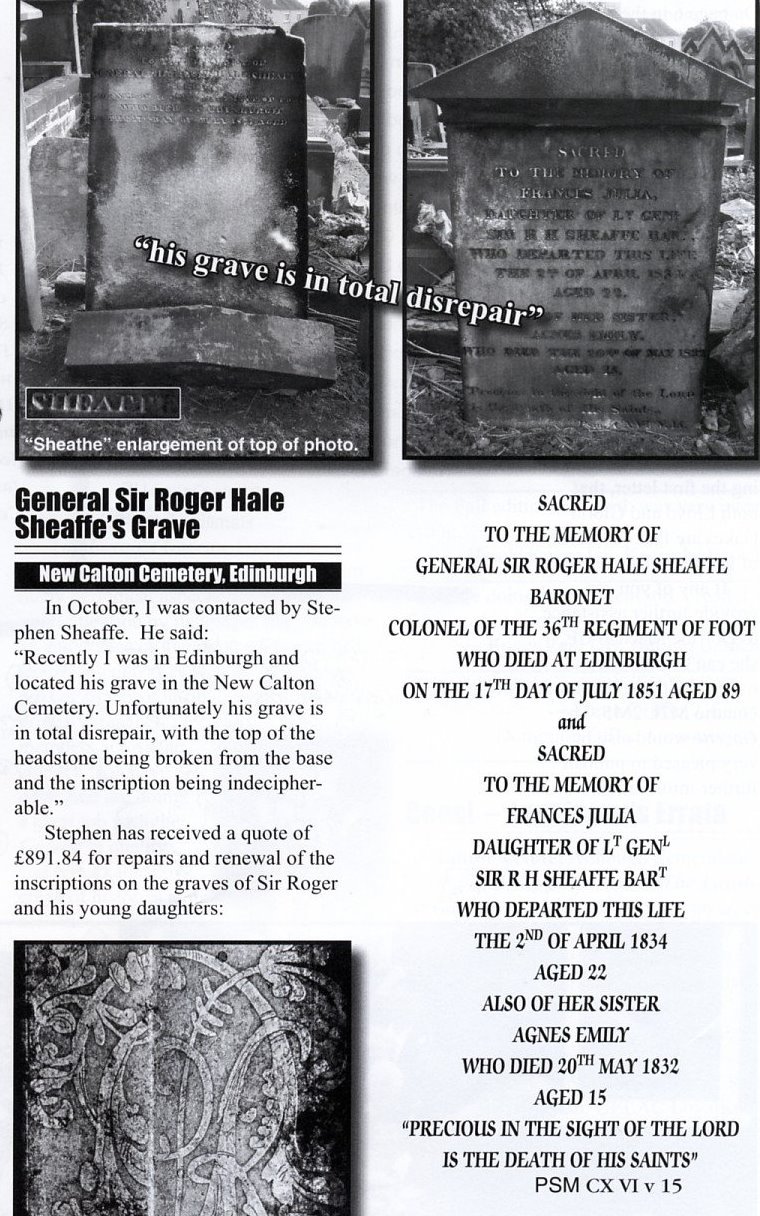

Sheaffe's Tombstone |

Some historians say the Battle of Queenston Heights has a significance out of all proportion to its military importance. Nevertheless, this crisis and the death of Isaac Brock during it, created a hallowed military memory and a national hero that significantly contributed to the creation of a nation by widening and enriching its history.

>Mr. Stephen Sheaffe, a descendant of William Sheaffe, Sir Roger Hale Sheaffe's brother, forwarded the following information regarding his famous ancestor."I am interested in all things history and especially family history. About 18 years ago

I wrote a family history book and it contained this information concerning Roger and his younger brother William Sheaffe.

Roger and William were both born in Boston. Their father, William, was the deputy collector of taxation for the British prior to the uprising by the rebels. (Should they be called freedom fighters?). Roger became a General in the British Army and his fame was made in the war of 1812. Younger brother William went to Ireland, married young, had 4 children and died young.

In fact, Uncle Roger reared William's children in Scotland. The son William and daughter Susanna immigrated to Australia. I am descended from Roger Hale Sheaffe's younger brother William - though Roger reared William's children.

William had 4 children: Roger, William, Susanna and John and the only son to have children was William (in the next generation). Susannah married W. Perry and she died at age 30 on Norfolk Island. Her son went on to become the Earl of Limmerick.

Roger Hale Sheaffe and Margaret had 6 children: three died as babies and three later. They all predeceased their parents. Margaret survived Roger and I believe she died somewhere near or even at Bath."

Copyright © 2010 W. R. Wilson