Foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

WAR OF 1812

The history of one's country begins in the heart.

|

|

War of 1812 |

Congress was summoned a month early by President Madison in November 1811. The demands for war were strident and compelling. The biggest booster for war, was the Kentuckian, Henry Clay, Speaker of the House of Representatives, who hammered away for hostilities, telling the members of Congress, "The conquest of Canada is in your power." He summoned up the spirit of 1776, declaring, "I cannot subscribe to British slavery upon the water." while hypocritically ignoring the fact that as many as 25% of his fellow Americans were slaves (By this time the population comprised 2.5 million, most of whom were of British descent and 6 hundred thousand blacks, nearly all from Africa.) He later claimed that the object of the war was to bring redress of injuries and Canada was the instrument by which redress would be obtained. Andrew Jackson joined in, the hullabuloo, by harkening back to Harrison's battle at Tippecanoe. "The blood of our murdered heroes must be avenged," he bellowed, conveniently ignoring the fact that Harrison had provoked the attack on the Natives. The frontier press shrieked, "The scalping knife and tomahawk of the British savages is again devastating our frontiers."

During this period of high tension and histrionics, one of the few voices of reason and restraint was John Randolf of Virginia, who left the Republican party to form a peace party called Quids. He opposed war and argued its real purpose was "a scuffle and a scramble for plunder." It was, he said, nothing but a cover for land grab. "One word like a whip-poor-will cried one monotonous tone: Canada, Canada, Canada."

Little provision was made for a naval increase, but the regular army was more than tripled in size and supplemented by 50,000 volunteers. Warlike speeches in Congress left little doubt about their intended employment - the invasion of Canada

Declaration of War

United States of America and Their Territories.

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That war be and the same is hereby declared to exist between the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and the dependencies thereof, and the United States of America and their territories; and that the President of the United States is hereby authorized to use the whole land and naval force of the United States to carry the same into effect, and to issue to private armed vessels of the United States commissions or letters of marque and general reprisal in such form as he shall think proper, and under the seal of the United States, against the vessels, goods, and effects of the government of the said United Kingdom.

When on June 19th, 1812 President James Madison proclaimed that a state of war existed between the United States and Great Britain, he issued a challenge to all American citizens to re-create the spirit of 1776 through the sword for the War of 1812 was a revival of the American Revolution. A common belief in England then, was that Madison's motive for war was to help Napoleon, and his "stab in the back" was timed to accomplish this.

Madison, the smallest president, was five feet four and tipped the scales at a hundred pounds. He wore only black suits which made him look smaller and thinner. He suffered from a nervous ailment known as epileptoidal hysteria, during which he experienced strange seizures and suddenly appeared frozen into immobility. These probably represented what is called a "conversion reaction," whereby the individual's frustrations are relieved by becoming rigidly immobile. Madison had brown hair, pale blue eyes and a weak and trembly voice, that could not be easily heard. One noticed his nose immediately, because it had once been frost-bitten and was permanently scarred. He was bright, had a good mind and was well educated. He was also meticulous,kept detailed records, but found it difficult to make decisions. Jefferson thought he would make a good president because he believed he would keep the peace. Thomas could not have been more wrong.

|

|

James Madison |

Hatred of Britain, a basic influence shaping American foreign policy, was fostered by a perceived British arrogance the former colonials found hard to endure. No longer would their ships suffer the indignity of being boarded and having citizens seized to staff British vessels. It mattered not to the Americans that Britain was in a life or death struggle with Napoleon. Britain naturally used any means at all to keep, "the knife at the throat of Napoleon." This included rounding up deserters, real or imagined, from ships suspected of harbouring its runaways.

A rebel priority in the Revolutionary War was the capture of Canada. They had unfinished business with 'Old Mother' England and many of them welcomed Madison's decision to finish finally what the revolution had only begun. Because Britain's presence on the North American continent was deeply resented war between the United States and the Great Britain resulted in open season on Canada, the northern bastion of all the King's men. It was the evil empire of the time, the source of all that was bad.

The people of Upper and Lower Canada were innocent bystanders caught up in a war between Great Britain and the United States. As a British colony they had little choice but to accept the consequences of British foreign policy, however, they harboured no hostility towards their neighbours to the south and found it difficult to conceive of how Americans could have any real grievance against them. Many of them were after all of American origin, linked to the republic by family ties and trade and commerce. While time had not completely eliminated the Loyalists' anti-American sentiment, it would have moderated it even more had not both countries for a second time become involved in war.

On paper at least the United States of America held all the right cards. It had seven and a half million Americans versus Canada's six hundred thousand inhabitants. Britain's main preoccupation was war against France. The mother country's life-and-death struggle with Napoleon claimed most of its military might and the little left over was scattered thinly here and there in the sparcely populated colony. Many of Canada's settlers were fresh from the States and their loyalty would likely be to their invading countrymen. Few Americans doubted the task would take long. Thomas Jefferson, who regarded Britain as "rotten to the core, greedy and corrupt," charged that she was "seeking by brute force and devious diplomacy to secure permanent domination of the sea and a monopoly on the trade of the world." Maintaining that the United States would easily strip Britain of her North American possessions, he boasted,

In His Own Words"The acquisition of Canada this year, as far as the neighbourhood of Quebec, will be a mere matter of marching, and will give us experience for the attack of Halifax the next and the final expulsion of England from the American continent."

Jefferson was president in 1803 when the United States doubled its size by acquiring Louisiana by purchase from Napoleon. This vast area which eventually formed all or part of fifteen states comprised forested midlands which gave way to open prairies and then arid plains. In this newly acquired territory there was a long history in which many Aboriginal tribes possessed reasonably defined areas and the relatively few whites there had co-existed peacefully with the tribes. Jefferson's plan was to remove all Natives living east of the Mississippi and Missouri and resettle them to the west of the Mississippi to make room for American settlements.

|

|

Thomas Jefferson |

This plan was stymied by Britain's close association with the Aboriginals. Whatever other reasons Madison gave for going to war the conflict was largely about land. The very existence of the Canadian colonies restricted America's growth and dimmed its destiny to control of the whole continent. The essential sticking point was ownership of the vast territories bordering the Great Lakes. Americans were goaded by what they saw as too cozy a relationship between the British and the Native tribes whose menacing presence augured death and destruction for settlers streaming into the traditionl lands of the Aboriginals.

Rightly or wrongly westerners believed that British policy was responsible for the troubles with the Aboriginals and the solution was simple: Canada simply had to be seized, if possible by peaceful means but failing that by force of arms. As far as the Americans were concerned Canada was not a party to the conflict, she was the prize. America had set its sights on Canada

The Nova Scotia Royal Gazette announced that "the madness which for many years pervaded the European continent has at length reached this hemisphere." The stunned and stupefied reaction of Upper Canada's Legislative Assembly was that the declaration of war "appeared to be an act of such astonishing folly and desperation as to be altogether incredible. That a government professing to be the friend of man and the great supporter of his liberty and independence should light the torch of war exhibited a degree of madness altogether incomprehensible."

The impact of this war on Canada's history is far more important than the bloody battles that were fought on land and lakes. It goes to the very roots of Canadian life for no other event was so great a factor in shaping our nation. For two and a half years Canadians of both races fought against an invader determined to seize their soil. The enemy invaded their shores, carried off their animals, burned their houses, destroyed their towns and forced their young men to fight and fall in battle. Canadian anguish was more awful because the invaders were blood of their blood and flesh of their flesh. This war, which more than anything else confirmed the determination of Canadians not to be Americans, explains the existence on both sides of the border of two English-speaking peoples. It forged a new nation.

Isaac Brock was the figure of fortune in this war. His energy, foresight, and military skill were worth battalions to the British. Even before the commencement of the conflict, Isaac Brock had warned Upper Canadians to be wary. In February 1812 some four months prior to Madison's declaration of war, Brock issued a proclamation declaring that sundry persons had recently entered the province "with seditious intent and to endeavour to alienate the minds of his Majesty's subjects." He suspected that the Americans would trust more to treachery than to force and in addition to deploying spies everywhere would attempt with lies and hollow promises of freedom and liberty to deceive Canadians. All things are fair in war and any method would be used to undermine the king's colonies.

Spying was a two-way street, however, and in 1808 an undercover expedition was sent to the United States by the governor of Nova Scotia. When its members returned they reported "It was amusing to hear the Americans talk of the ease with which they can possess themselves of the British provinces. No man of either party seems to imagine there would be any difficulty in effecting the project, that is, capturing British North America." Andrew Jackson said it would be a military promenade. An American visitor to Upper Canada in 1810 said that based on his inquiries, if 5000 American soldiers were sent to the colony with a proclamation of independence for Canada "a great mass of the people would gladly join the American government." It was widely believed by American leaders that many if not all of the late Loyalists, that is, Americans who had come to Canada solely for the free land, would prefer Congress over King. To these more recent arrivals the war would be one of liberation freeing them finally from Britain's heavy yoke.

|

|

Andrew Jackson |

|

|

Andrew Jackson |

Henry Clay confidently declared, "It is absurd to suppose we will not succeed. We have Canada as much under our command as Great Britain has the ocean and the way to conquer her on the ocean is to drive her from the land. I am not for stopping at Quebec or anywhere else, but I would take the whole continent from her and ask her no favours. I wish never to see peace until we do. God has given us the power and the means. We are to blame if we do not use them. The conquest of Canada is in your power. I trust I shall not be considered presumptuous when I state what I verily believe: that the militia of Kentucky are alone competent to place Montreal and Upper Canada at the feet of Congress." [See Below *]

|

|

Henry Clay |

One enthusiastic entrepreneur offered to take on the job and capture Canada by contract. "I will raise a company and take it within six weeks." The American Secretary of War really got caught up in the bombastic bravado, threw caution to the winds and boldly vowed, "We can take Canada without soldiers." Emboldened by such boasts another confident congressman asserted, "The Falls of Niagara itself could be resisted with as much success as the American people when roused into action." Shortly after the war got underway the Speaker of the House of Representatives, Henry Clay, solemnly pledged that he would never consent to any treaty of peace that did not include the cession of Canada.[**]

Henry Clay and those who shared his militant views were dubbed War Hawks by Randolf scorned the War Hawks' "cant of patriotism" charging that if war came, it was because of American aggression. "Agrarian greed not maritime right urges this war.

The War Hawks said national honour demanded a fight which if successful would conquer Canada, end the Aboriginal menace on the western frontier and throw open the plains and prairies for settlement. Natives were so riled by the frenzy of Americans to occupy the western prairie, they filled the mouths of any they killed with earth to signify their insatiable demand for ever more Aboriginal land. Land hungry frontiersmen of the old North West coveted the fine, fertile, wooded peninsula of Upper Canada into which several thousand American immigrants had already penetrated.

Despite the fact that these newly-arrived American settlers were reasonably contented under the "British yoke," the War Hawks expected them to "rise as one man" and rally to the colours once they saw the Stars and Stripes fluttering in the breeze.

Americans swaggered into the War of 1812 totally unprepared for the scrappy fight a few soldiers north of the border would give them. In spite of being sparsely populated and divided by language and governments, Canada was not prepared simply to roll over, play dead and pass into the possession of the United States. Canadian repudiation of the republic was to be reflected in the fine military feats of locally raised militiamen and the small garrison of British regulars under the inspiring leadership of "a first-rate red-coated general."

|

|

Isaac Brock |

When mild-mannered James Madison signed the declaration of war he set loose the Sons of Liberty who immediately mobilized for mayhem. These anti-British rabble-rousers stormed through the streets, wreaking vengeance and unlawful excesses on any suspected Tory supporters of Britain. The mob violence they unleashed included assault, theft and the destruction of whatever they did not steal.

On the eve of the War of 1812 Upper Canada still lacked a sense of community. The new American settlers were not yet Canadians, were largely indifferent to politics and were preoccupied instead with their own world of "stumps, seeds and sows." Non-Loyalist Americans in Upper Canada found themselves in a difficult situation at the start of the war. Those entering Upper Canada after the Revolutionary War never expected another conflict with Canada. Many had family connections in the states near the border so the conflict became a kind of civil war with relatives and family on both sides ofthe border enrolling in their respective militias. Few expected war to happen and when it did there was panic.

Hull's proclamation, which declared he had come to free them from tyranny, was considered by Americans as ludicrous because they could have retired across the line at any time. Now a proclamation made it treasonous for anyone to attempt to cross the border and those who might have wanted to return to the states found that not only were they unable to do so, but they were placed under arms in Upper Canada. Most had decided that if Hull invaded Upper Canada and they were ordered by British authorities to march against him they would not do so. But they also decided that "not a man would join Hull to fight against the King." Some soon discovered, however, that they had little choice in the matter. An American on the Canadian side recorded seeing "waggons daily coming in from the backwoods loaded with men, women and children, many of whom were in a very distressed state; they begged for permission to cross to the United States from where many had recently come. Instead they were immediately made militiamen, their horses were confiscated and they were employed in the service of the government."

Angry reactions to the war were not confined to one side of the border. At Queenston on April 17th an outraged young citizen showed his contempt for Congress by firing his gun across the Niagara River at no one in particular. The difference was that lawlessness was not allowed in Upper Canada. The youth was immediately apprehended and committed for trial while two Upper Canadian magistrates hastily tendered apologies to the citizens of Lewiston for this untoward incident.

Five days later at Fort George, a vigilant Isaac Brock, a soldier of sound military insight and professional skill with a corporal's guard of sixteen hundred regulars, reported seeing some three hundred men in plain clothes patrolling the shore on the American side of the river. He suspected the United States' government entertained hopes of an incident occurring on the frontier that would provoke a quarrel. He cautioned all troops to prevent any pretext for retaliation. Brock assigned members of the militia to patrol the river and established a method to sending messages across the peninsula using warning beacons, signals that could be seen from one beacon to another using smoke and fire. An order was issued on the 2nd of October directing one-third of the troops at Fort George "to sleep in their clothes fully accoutred and ready to turn out a moment's notice." On the sixth another order required the whole of the regular troops and the militia to be under arms by the first break of day and not to be dismissed until full daylight. Brock also ordered troops known as the Niagara Dragoons to be prepared at a moment's notice to ride like the wind with military messages. Although he had little in the way of military resources Brock endeavoured to make the most of what he had by mounting cannons strategically along the river.

|

Despite the scarcity of military might Brock's earliest problems were psychological. "A full belief possesses the people that this province must inevitably succumb." He expected a majority of Upper Canadians would be cautious combatants, hesitant to take up any arms at all, since many were recent arrivals from the republic who would be loath to fight their former neighbours.

Meanwhile on the other side of the Niagara River the Americans were nervously noting the buzz of activity taking place in the Canadian colony. One observer, who was doubtless receiving information from informants, reported, "New troops are arriving from the Lower Province constantly and the quality of military stores, etc. arriving is astonishing. Vast quantities of arms and ammunition are passing up the country, no doubt to arm the Indians around the Upper Lakes. One third of the militia of the Upper Province are formed into companies called Flankers, and are well armed and regularly trained one day a week. A volunteer troop of horse has lately been raised and have drawn their sabres and pistols. The noted Isaac Swayze has received a captain's commission for the flying artillery of which they have a number of pieces. They are repairing Fort George and building a new fort at York. They are using every argument and persuasion to induce the Indians to join them and I understand the Mohawks have already volunteered their services."

In his message to Congress on 1st of June, 1812, President Madison read his long list of lamentations, charging Britain with a series of hostile acts that "violated the American flag on the great highway of nations." He grouped his accusations under five headings, the first four of which pertained to maritime quarrels about which the United States had complained for some time. Marine disputes were intensified by a British Order in Council passed on January 7th, 1807, which prohibited neutral nations from trading with France and her allies and ordered the capture of any ships failing to comply with British regulations. The Orders were Britain's response to France's Berlin Decrees which closed European ports to British ships and authorized the seizure of any vessel dealing with Britain.

As the largest neutral trading nation involved the United States was caught in the economic crossfire and suffered more than most other countries. British ships blocked American trade by hovering off shore and harassing commercial ships entering and leaving American harbours. Britain's position was simply: "If you are not for me, you must be against me." Her relations with the United States were described at the time as being "negatively friendly."

While the hassling and harassing of America's vessels off its very shores was an affront to its sovereignty, a far more humiliating indignity was being suffered by American citizens. Britain was habitually short of men to man His Majesty's ships. British sailors worked long hours at hard labour, were paid very little and were subjected to the harsh discipline of the cat-o'-nine-tails. Desertion was widespread and British ships' crews were maintained largely by press gangs which searched for and seized any able-bodied men they could find to force them into military service. Some of those who were impressed protested that they were American citizens, but Britain simply ignored America's naturalization laws and asserted that any English-speaking person who was not an inhabitant of the United States on or before the date of its independence was an Englishman. The official position was once a British subject, always a British subject. No allowance was made for the transference of citizenship to the United States. British cruisers arbitrarily stopped and searched American vessels for deserters. The British were surprised at the American demand that they stop impressing seaman to serve on His Majesty's ships. This was an "ancient and accustomed practice of impressing seamen from ships of a foreign state" and Britain had no intention of abandoning it.

One flagrant and particularly inflammatory incident known as the Chesapeake Affair occurred in June, 1807, when the U.S. frigate Chesapeake was forced to surrender to search by H.M.S. Leopard off the coast of Virginia. In an act of supreme arrogance, the British fired without warning on the U.S. frigate inflicting casualties and then boarded and removed one English deserter and three Americans who had served in the English navy. The event aroused war fervor in the United States until Britain offered reparations and tempers cooled. Thomas Jefferson, president at the time, charged the British dragged thousands of American citizens on board British ships of war and forced them"under the severities of British discipline to risk their lives in distant and deadly climes."

® |

|

HMS Leopard Fires Upon USS Chesapeake |

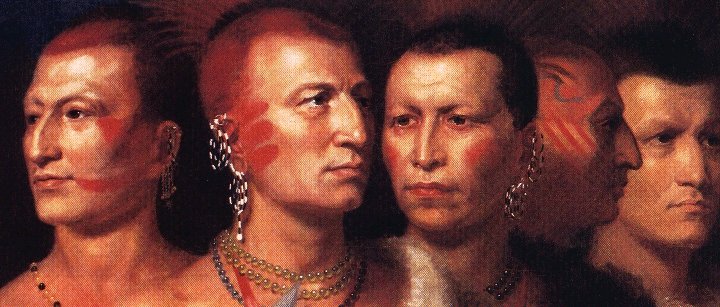

The other great fear and frustation of Americans was the Native nations who were engaged in a war of attrition against the endless encroachment of American settlers on their lands. Madison's fifth accusation dealt with this ongoing warfare against the allied tribes on the western frontier. Their close contact with British traders and garrisons greatly spurred the suspicion and hatred Americans felt towards the British. Madison blamed the frontier fighting on Aboriginal gullibility and European rascality. He charged that Native warriors under ,Tecumseh, a Shawnee chieftain and a truly great Indian, had worked for years to build a confederatin of Indian tribes to confront the Americans on equal terms and halt its acquisition of Indian lands. He and his followers were considered "willing tools in the hands of England." Tecumseh and his dream marched with British imperial strategy to establish a "neutral Indian state."

It was charged by the Americans that the British were instigating and arming Aboriginal warriors to oppose American settlement. There was little truth in these charges. Brock in the spring of 1811 issued clear orders to his officers stationed on the frontier. "I am decidedly of the opinion that upon every principle of policy, our interests would lead us to use all our endeavours to prevent a rupture between the Indians and the Americans."

However, Brock's policy was not motivated by the principle of preventing either Indian or American death and destruction. He feared a forthcoming war with the United States and knew Britain needed the support of the Indians if it had any chance of surviving the coming conflict. It was necessary to prevent the loss of Indian life in strife they could not win and foster a web of military alliances with the various tribes whose warriors would side with Britain in any conflict to come.

Settlers whose relentless quest for evermore land was "a transcontinental juggernaut called westward expansion". Ploughs and axes were relentlewss driving the tribes further and further across the great great forests and plains. The relationship of Aboriginals and the colonists formed a complex phase of American history, one marked by avarice and unprovoked ruthlessness of colonists against the Native people.

|

Americans felt they had to eliminate the British influence in the uncharted areas between the United States and the Rockies which impeded their drive to populate the continent. This could only be accomplished through the sword. However, support for Madison's War was not unanimous throughout the United States. Americans in the New England States ignored the conflict and carried on business with Britain as usual. Madison accused British secret agents of trying to get these eastern states to sever their association with the American union, action he described as "a mode of warfare distinguished by the deformity of its features and the depravity of its character. This war is the last resort of an injured nation." "We are going to fight," said Andrew Jackson, [***] "to remedy the hurt national pride we are suffering on the high seas by fighting fiercely on land to eliminate all opposition to our seizure of ever-more of the frontier forest and prairie land inhabited by scattered Native tribes."

On June 4th, 1812 the House of Representatives approved the declaration of war by a vote of 79 to 49. A Congressman named Josiah Quincy described the invasion of Canada as "a cruel, wanton, senseless and wicked attack upon an unoffending people, bound to us by ties of blood and good neighbourhood undertaken by young politicians with their pin feathers yet unshed to whom reason justice and pity were nothing and revenge everything." The bill was sent to the Senate where it was debated for twelve days before being approved on June 17th by a vote of 19 to 13.It was forwarded to President Madison who signed it into law and declared war on Great Britain on June 18th. As of that date a state of war existed between the United States of America and Great Britain. Although Canada was not mentioned in the declaration, it was the field on which the battles would be fought. On the 23rd of July Britain's Orders in Council were formally cancelled, action the the U.S. considered too little too late. Madison had decided that Canada was "a rogue's harbour" and had to be eliminated. Britain did not formally declare war on the United States until January 9th, 1813.

With a population of some six hundred thousand people in pioneer settlements dotting half a continent, the vast wilderness called Canada was defended by a few thousand troops. The United States with a population of 7.5 million, made the war a contest between David and Goliath in which Canada was the prize, a pawn between two big players. One of the reasons why the British were able to block the American invasions was their control when hostilities began of the Great Lakes. The land around the lakes was essentially a trackless wilderness, small villages, towns and forts tied together by a poorly developed system of roads. The most effective means of travel was by shallow draught schooners or sloops or countless smaller craft that plied the lakes and rivers.

War had been declared against Great Britain and the serious fighting would have to be done by her soldiers. Despite this the conflict as far as British leaders were concerned was considered a backwoods clash in a minor conflict, the bulk of Britain's military might being fully occupied fighting France in Europe. Britain's gigantic struggle with Napoleon consumed most of her material and human resources and Canada's cause had to make do with the little that was left over which was not much. If it had been otherwise perhaps the outcome of War of 1812-14 might have been different.

|

In 1812 British forces in the Canadas numbered 5600 regulars and fencibles of which 1200 were stationed in small, widely scattered garrisons in Upper Canada where much of the fighting was expected to take place. British settlements in the maritime provinces were relatively free from conflict largely as a result of the presence of the British fleet at the Halifax naval base and the violent opposition to the war that existed in neighbouring New England states.

According to Anglican Bishop John Strachan, one of Upper Canada's leading citizens, incompetent British military leadership nearly lost Canada to the Americans. Strachan was particularly critical of the "weakness and imbecility" of the British commander-in-chief, Lord Prevost."

Strachan stated this in no uncertain words on October 13th, 1813.

In His Own Words

"Our Commander-in-chief has produced all our defeats. If this country falls he only is to blame. Never was a country lost so shamefully as this one has been or will be. Not the smallest vigor has been displayed, there is no campaign plan, everything is left to chance and all our movements are directed not by us but by our enemy. General Prevost appears not only ignorant of the art of war but destitute of common sense."

|

|

John Strachan |

The forty-five year old Prevost was born in New Jersey, the eldest son of a Swiss-born army officer. As a young man Prevost joined his father's regiment, the 60th Foot, also known as the "Royal Americans." In 1803 he was created a baronet and promoted the major-general. The same year he was appointed governor of Nova Scotia and in 1813 governor of Canada and commander of all British forces in North America.

Prevost, a cautious, conciliatory Swiss was appointed with a mandate to mobilize. Cautioned to move slowly and avoid alarming the Americans, Prevost was to some extent hampered in his conduct of the war by the cautious instructions of the Home authorities preoccupied with the struggle Europe. A well-meaning official, Prevost was more effective as a politician than a military leader. He had none of the instinct that seizes the occasion and "strikes quick and hard and extorts success." The tactic of "this tiny, light, gossamer man"was defensive, the strategy promoted by London whose preoccupation was the safeguarding of Quebec, the only permanent fortress in the Canadas.

Prevost's order of the day was "forbearance until hostilities are more decidedly marked." In a communication to Brock dated July 10, 1812 a harried Prevost declared his policy. "I consider it prudent and politic to avoid any measure which can have a tendency to unite the people of the United States. The Government of the United States, resting on public opinion for all its measures, is liable to sudden and violent changes. We must adapt our measures to the impulse of those with influence over the public mind." He recommended a policy which would "promote the dwindling away of such a force (the American army) by its own ineffectiveness." He wisely confirmed Brock's appointment as temporary administrator of Upper Canada.

|

|

Sir George Prevost |

|

|

Anne Prevost |

Prevost's eighteen year old daughter, Anne Elinor, kept a diary throughout the war and recorded that when the province was called to arms her mother was "tortured with anxiety." She was undoubtedly apprehensive for the sake of her husband beecause of the consternation the coming conflict would cause him. Her concerns proved to be well founded for George worried his way through the war and regularly reminded his superiors of his difficulties. In a letter to Lord Bathurst dated 14th August, 1814 Prevost decried American naval supremacy.

In His Own Words"The naval ascendancy possessed by the enemy on Lake Ontario enables him to perform in two days what our troops going from Kingston to Niagara require from 16 to 20 days of severe marching to accomplish. Their men arrive fresh, whilst ours are fatigued with exhausted equipment."

In another letter dated November 21st, 1814 Prevost described a situation that was potentially very serious."A body of 1500 mounted Kentuckians with rifles, tomahawks and scalping knives reached the Grand River on their way to Fort Erie. Their passage was disputed by a party composed of Indians and members of the 103rd Regiment. Both the American advance and then their retreat were marked by plunder and devastation which could have led to the ruin of the whole country lying in their line of march."

Two offensives conducted by Prevost, first at Sackett's Harbour and later at Plattsburg, ended humiliatingly. Ordered to take Plattsburg in September 1814 Prevost invaded the United States with an army of close to 15,000 of Wellington's splendid peninsular veterans. He stopped short of the lightly-defended town unable to bring himself to order the final assault. Instead he goaded his Lake Champlain fleet commander, Captain George Downie, into attacking the American Navy anchored in Plattsburg Bay. The battle ended in disaster for the British. The Americans, fighting in the manner and place of their own choosing, destroyed the British fleet.

Prevost had promised Downie a simultaneous land attack but didnít order the assault until the naval battle was almost over. As soon as he learned the British fleet had lost Prevost ordered a general retreat. He withdrew against the advice of his senior officers who felt Plattsburg was still within easy grasp. Frustrated officers complained bitterly about serving under "such a Goose as our little nincompoop." Prevost was recalled in 1815 because of criticisms of his military judgement. Before his court martial could be convened he died of an unspecified illness, perhaps its name was despair.

Isaac Brock was an man of destiny, a military officer who believed the best defence was offence and fortunately for Canada he was given freedom to follow his own best judgment. In a letter to Brock Prevost stated he would "not attempt to prescribe specific rules for your guidance. They must be directed by your discretion and the circumstances." Directed they were for Brock's astonishing victory at Detroit [****] gave hope to the weak-hearted and faint-spirited and inspired Canadians to believe their giant foe could be fought successfully.

|

|

Vessel Bombarding Detroit |

Strachan had only praise for the lower-ranked officers. As for the men of the Upper Canadian militia, Strachan said they were equal to anything, but were wasted by sickness and by being "frittered away attempting to defend too many points." He lauded General Isaac Brock's "invaluable qualities," particularly his willingness to "carry the war" into the United States.

To a considerable extent Canada's survival resulted from the bungling of American commanders. They had the advantage of choosing when and where to strike, but selected the wrong places. If a determined attack had been made on Montreal and all traffic in British men and materials stopped from moving up the St. Lawrence River, an American victory might well have been prompt and decisive.

When the war was not won as quickly as many Americans thought it should have been, the papers had a field day finding fault with their leaders. One editor eagerly criticized the conduct of the war with a bit of doggerel.

The nation pillag'd of its fame,

Is sunk in infamy and shame.

Six months are past and yet the foe,

Laughs at our force and scorns the blow.

How vulnerable was Upper Canada? Troops fighting on the Niagara frontier were fed with flour from England and pork and beef from Cork, Ireland. Not only provisions but every kind of military and naval stores, every bolt of canvas, every rope yarn as well as guns, shot, cables, anchors, and all the necessitites required to supply a large squadron, arm forts, and provide arms for the militia had to be brought from Montreal to Kingston, a distance of nearly 200 miles by land in winter and in summer by flat-bottomed boats which had to be towed up the rapids and sail up the river exposed to the shot of the enemy without any protection. Had the Americans stationed four field guns with a corps of riflemen on the banks of the St. Lawrence, they could have cut off supplies without risking one man. If they had done so with any kind of spirit, Upper Canadians would have had to abandon their homes as well as Kingston and the fleet on lake Ontario. They would have been forced to confine themselves to the defence of that part of the Lower Province that came within the range of their own empire, that is, the sea, which Britain controlled.

American forces were squandered on isolated attacks in non-strategic locations. According to one historian they fought at the extremities and failed to find the beating heart and stop it. Americans also suffered from a fixed and false assumption about the loyalty of Canadians. Bellicose American westerners, the biggest backers of the war, believed most Upper Canadians would flock to their side, for the bulk of the newly arrived residents in the western part of Upper Canada were Americans who had come to Canada for free land, not loyalty.

In 1812 at least one-third of all inhabitants of Upper Canada had been born in the United States or were descendants of Americans. Nevertheless, most served their adopted country loyally and obeyed the call to arms and the militia. Some historians also credit our survival to the loyalty of French Canadians who refused to join the Americans. A popular song of the time, The Noble Lads of Canada reflected Upper Canadian patriotism.

Oh, now the time has come, my boys, to cross the Yankee line,

We remember they were rebels once, and conquered old Burgoyne;

We'll subdue these mighty democrats, and pull their dwellings down,

And have the States inhabited. by subjects of the Crown.

Canada survived because it was better prepared for war. Britain provided the essentials for its defence - a naval force on the Great Lakes and adequate regulars led by skillful and energetic professional officers like Isaac Brock. His early offensive victories against a foe many felt could not be beaten served to stiffen the spines and lift the spirits of doubting Canadians. At this most critical time of Canada's existence, Brock's vision and valour altered the course of history. "The appearance of one dominating individual in a critical position at a decisive moment has often altered the course of events for years, even generations." [*****]

The War of 1812 was a conflict of contradictions. It was declared after a primary cause had been removed. One of the major participants, Great Britain, considered it a side-show, a minor distraction from the primary struggle in which Britain was engaged in Europe. For many Americans it was a bare-faced aggression, incompetently directed and stained by cowardice and stupidity. American pride was salved solely by their unexpected victories at sea and on the lakes. The war failed to settle the major causes mentioned in declaration of war. One of the bloodiest campaigns, the Battle of New Orleans, took place after the peace treaty had been signed by both parties, but not formally approved by the legislatures. Canadians saw it as a successful defence of their independence and they wrote of it with pride. Both sides declared they had won the war. The fact remains that the Americans attempted but failed to conquer Canada. They invaded Canada and were repulsed.

Canadian and American tradition glorifies victories achieved during the war, while British tradition barely recognizes the conflict at all. The truth about the war was often distorted or ignored by historians, who were under public pressure to emphasize and sentimentalize their country's role in the conflict in order to promote national pride. History was recruited to serve patriotism and it became a recital of heroes and victories. American military men were very adept at producing under trying circumstances the apt and memorable phrase, a "golden statement" which was quoted thereafter by an adoring press and public. "We have met the enemy and they are ours." "Don't shoot till you see the whites of their eyes." "Don't give up the ship." In the latter case the crew of the Chesapeake were ,in fact, forced to abandon the ship after action that lasted less than fifteen minutes. The warning by the Greek writer, Lucian, that "a historian among his books should forget his nationality" was largely ignored by historians of this conflict.

When details of the peace treaty reached the United States, Americans were astounded to discover that it contained no clauses forbidding the seizure by Britain of American sailors, no restrictions on British support for frontier Aboriginals and no restraints on British interference with American commerce on the high seas. These primary causes of the conflict were unresolved. Newspapers were quick to criticize a treaty, that failed to mention the major causes of the conflict. Despite this the cessation of hostilities was widely welcomed, for "it pleased God to restore peace to this bleeding land." Although the United States achieved none of its avowed aims for going to war, popular legend there soon converted defeat into an illusion of victory. This was bolstered by the one-sided win of General Jackson at New Orleans. This victory after the peace treaty had been signed confirmed in the eyes of Americans their country's triumph and it served as the clinching climax to their celebrations.

In Upper Canada the Niagara district, in particular, suffered severely from the war. An American gave this view of Upper Canada in 1813. "All the schools are broken up and no preaching is heard in all the land. All is gloomy - all is war and misery." A traveller to the area described what he saw in 1815. "Everywhere I saw devastation, homes in ashes, fields trampled and laid waste, forts demolished, forests burned and blackened, truly a pitiful sight." The Town of Niagara had been burned to the round as had the village of St. Davids. All was devastated. The countryside was a wasteland, the cattle carried away and buildings burnt by the enemy. A traveller in the western district in 1816 wrote: "I was sensibly struck with the devastation which had been made by the late war: beautiful farms, formerly in high cultivation now lay in waste; houses entirely evacuated and forsaken; provisions of all kinds very scarce; and where once peace and plenty abounded, poverty and destruction now stalked over the land."

This vivid description of an early morning raid indicates how the war affected one homestead. "On the morning of 15th of May, 1814, as my mother and I were at breakfast, the dogs made an unusual barking. I went to the door and discovered the cause. The hillside was covered with American soldiers. They had landed at Patterson's Creek, burned the Mills and village of Port Dover and then marched to Ryerse. Two men stepped from the ranks, selected some large chips, came into the room where we were standing and took coals from the hearth without speaking. My mother knew what they were going to do. She went outside and asked to see the commanding officer. She entreated him to spare her property because she was a widow with a young family. He said he regretted that his orders were to burn, but he would spare the house. All other buildings were to be torched. Very soon we saw a column of smoke arise from every building and what at early morn had been a peaceful, prosperous homestead at noon was only smouldering ruins."

Remembrance of incidents like the above burned deeply into the hearts of many inhabitants of the province creating an anti-American prejudice that lasted for years. Multiply this tragedy by hundreds of other such incidents and it is not hard to see on what foundation the Province of Ontario was built. From the close of the War of 1812 can be dated the strong feeling of British allegiance which was so characteristic of the province of Ontario. History texts of the time highlighted two facts in connection between the United States and Canada: the coming of the Loyalists following the American Revolution and the fighting of the War of 1812. Both strengthened the sense of British allegiance. It is little wonder that in Upper Canada when the war ended and word of peace finally arrived,"Our forefather's hearts lept with joy as they thanked Great God for that inestimable blessing of peace."

One Canadian historian commented that "All Canada gained from the War of 1812 was the right to remain British." Surely this after all was exactly what Canadians wanted. Canada taught her enemy the lesson they most needed to learn: Canada was not for sale or to be invaded with impunity. Americans finally realized a basic fact of North American sovereignty: that Canada was in the British Empire for keeps. The war acted as a screening process, straining out the most disaffected and leaving a community largely convinced of or converted to a vociferous provincial patriotism.

The War of 1812 became enshrined in memory, and the source of the Tory myth in Upper Canada. Prominent Upper Canadian Conservatives like John Strachan and John Beverley Robinson emphasized that we had learned these lessons from the war: beware the danger of American-style radicalism; recognize the virtue of commitment to British values; and admit the right of men like them to rule because they had saved the province from the Yankees. This became the rationale for the rights claimed by the Tory oligarchy, the Family Compact.

The Upper Canada Preserved medal was struck by the Loyal and Patriotic Society of Upper Canada for "extraordinary instances of personal courage and fidelity in defence of the Province" during the War of 1812. The medal depicts the British lion protecting the Canadian beaver from a hovering American eagle. Flowing between them is the Niagara River. The inscription is: Upper Canada Preserved. The medal was never awarded because the war ended and the list of those entitled to receive it turned out to be too long for the society's limited budget.

|

"The tendency among some to disparage the 'little' war of 1812 and its glow in past tradition ignores the fact that the very creation of heroes and legends out of the conflict reveals the impact that it has made on popular consciousness. Has Canada since World War II found a military hero equal to General Brock?"

Bitter memories smouldered long after the war was over and ex-militiamen oft recalled the conflict and their courage with songs such as this.

Our sires took the country when Wolfe did command:

Though Brock you have murder'd, we will keep all our land!

We will make you repent so heinous a deed:

The Royal Canadians will make your heart bleed!

We will cook in molasses your punkin and pork,

For the booty of Dearborn, and the plunder of York!

We will conquer our foes and tread on their toes,

With God Save the King, and bad luck to his foes!

"The Maple Leaf Forever."

"At Queenston Heights and Lundy's Lane,

Our brave fathers side by side,

For freedom, homes and loved ones dear,

Firmly stoood and nobly died;

And those dear rights which they maintained,

We swear to yield them never,

Our watchword ever more shall be,

The Maple Lead forever."

|

|

Veterans of the War of 1812 |

Taken in 1861, this photo is of surviving Canadian veterans of the War of 1812. Men who may have seen Brock and Tecumseh, these courageous survivors of the conflict inspired the belief that the Canadian militia made a signifcant contribution to the cause. No doubt they did in conjunction with our Native allies and the British Red Coats. Their combined efforts made possible the creation of the Dominion of Canada, which came into being six years after this photograph was taken. [The War of 1812 by Victor Suthren.]

. [*] Ironically 50 years later in 1862, Henry Clay's son, James, who supported the Confederate States in the American Civil War, sought refuge in Niagara from officials of the United States who were attempting to arrest him for rebellion. Fortunately for Clay and hundreds like him, the United States had failed in its earlier attempt to capture Canada. [**] Clay was more than happy to hasten to Ghent to negotiate a peace treaty that settled none of the causes that led to war he and his followers were largely responsible for starting. [***] Andrew Jackson (1767-1845) victorious American leader at the Battle of New Orleans and 7th president of the United States. [****] The Military General Service Medal, 1793-1814, issued in 1848 was given to all including Aboriginals who took part in the capture of Detroit. It is surprising that the military engagements at Queenston, Miami and along the Niagara peninsula, which were classified as battle honours, were not deemed worth of bars to the General Service Medal. [*****]David Lloyd George, Prime Minister of Great BritainCopyright © 2011 W. R. Wilson