foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

Wolfe vs Montcalm

History is written by successful soldiers.

"Battles are won by slaughter and manoeuvre. The greater the general the more he contributes in manoeuvre, the less he demands in slaughter. Nearly all the battles which are regarded as masterpieces of the military art have been battles of manoeuvre in which very often the enemy has found himself defeated by some novel expedient or device, some queer, swift, unexpected thrust or strategem. In such battles the losses of the victors have been small." Winston Churchill

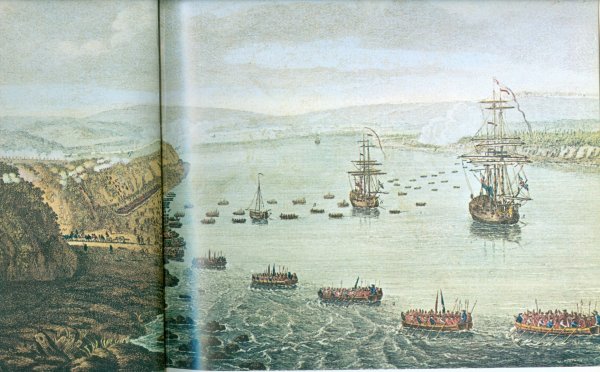

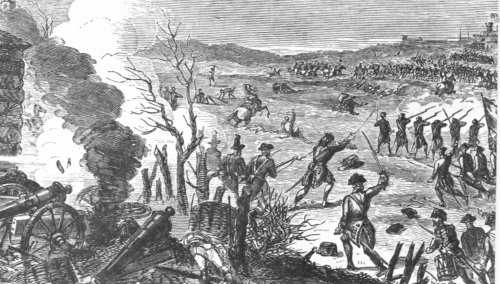

At 1:30 a.m. Redcoats in rowboats approached the cliff. By dawn 5000 men were on the Plains of Abraham prepared for battle. By noon that day, it was all over.

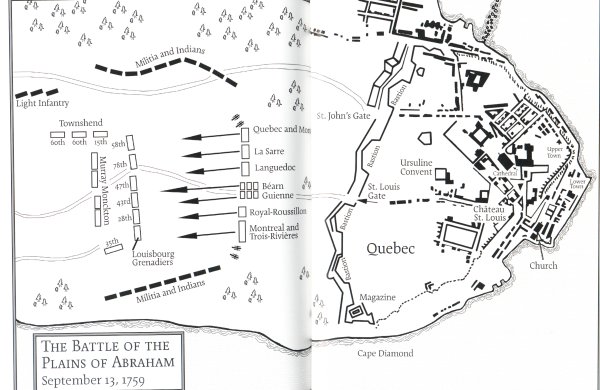

Wolfe had avoided the high ground immediately outside the fortress and arrayed his troops on the flat Plains of Abraham. Meanwhile Montcalm's men occupied the high ground.

In those brief moments before combat commenced, the autumn air was hushed and the battlefield bedecked with the colourful costumes of soldiers waiting for the word. Misfortune beckoned Montcalm and he obeyed the summons. The silence was broken by his barked command: "Marchez." Trumpets blared, drums rolled and standards snapped in the wind as white-coated regulars and a motely mix of grey-clad militia made their move down from the highground to face the British forces standing like stone statues on the level battlefield. The iron will of the redcoated regulars was unnerving to the motely mix of the French forces rapidly approaching.

|

|

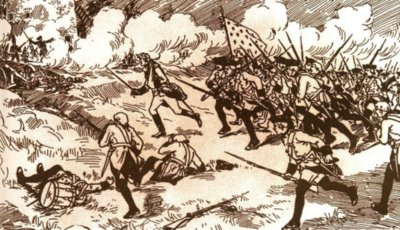

The Plains of Abraham, September 13, 1759 |

|

|

The 'Decisive Day' - September 13, 1759. |

|

|

|

The opposing forces were about the same size, but Wolfe's men were more than a match for te combination of white-coated French regulars, Canadian militia and aboriginals. Led by their gallant commander in a grimly balanced life and death contest, the French regiments in measured movements left their lofty heights and advanced in column across the plain towards the long line of British soldiers. A Canadian militiaman afterwards remembered Montcalm "waving his sword as if to excite us to do our duty." The troops surged forward firing volleys at Wolfe's magnificently motionless men. [See Below *]

|

All the while French ranks were being riddled by the rapid fire of grape shot from two British field pieces that had been dragged up the heights. Montcalm's forces included a good many Canadians who could fight effectively in their own way, - keep down, crawl across the battlefield, take aim, and fire. They found the European custom of combat idiodic and had little desire to stand and face the fire required in a stand-up battle. As was their custom after firing, the Canadians dropped to the ground to reload, a tactic that became distracting, disconcerting and disorienting to the French regulars, who depended on close formation for effective fire control.

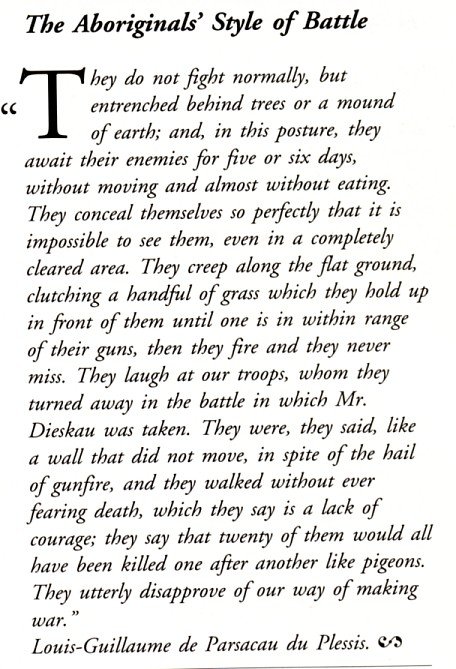

There were no warriors with Wolfe, but Montcalm could count on 1000 braves who were among those firing the first shots of the battle. According to one British soldier, Aboriginals "were on our left flank and rear and along the face of the hill below our right. where bushes afforded them all the advantages they could hope for." As the two armies closed for the clash, the Iroquois braves and the colonials inflicted a steady, accurate fire upon the British. "The enemy," wrote one British officer, "lined the bushes in their front with Indians and Canadians and I dare say had placed most of their best marksmen there, who kept up a very galling though irregular fire upon our whole line." Normally serving as scouts and skirmishers, the braves applied in combat their hunting skills of concealment, surprise and speedy dispersal. The wily warriors "who come like foxes in the woods, attack like lions and flee like birds" were effective extras in battle, their menacing presence alone serving to unnerve those facing their savage terror.

|

|

In this kind of conflict an army had to be kept focussed with the greatest possible force concentrated on the field of battle. Montcalm's forces failed to follow this fundamental military principle. Disoriented by the militia movements they began to break formation and fire wildly at will, their white ranks growing more disorganized as they advanced. They shot in ragged bursts of smoke in an undisciplined attempt to panic the scarlet figures before closing to confront that mute wall of redcoats in a life and death-struggle to decide the fate of half of America. According one modern historian,[**] it was not just a conflict for a continent but the turning point in the entire history of the world.

|

|

|

British troops possessed the most precious quality in war: le calme dans la colere. (calm during anger) With cool composure the seven red-coated battalions stood facing the French in unflinching fortitude, seemingly more intent on the orders to come than on the French forces advancing wildly towards them. As he awaited the assault of the Montcalm's fractious forces, Wolfe's thoughts might have mirrored Napoleon's military maxim: "Never interfere with the enemy when he is in the process of destroying himself."

Montcalm in turn might have taken note of Napoleon's advice to generals : "The first quality of a general in chief is to have a cool head which receives exact impressions of things, which never gets heated which never allows itself to be dazzled by good or bad news. Napoleon "The French, who were less than a hundred and fifty yards apart, quickened the pace. As each British soldier fell in the face of the French musket fire, his place was quickly filled by another. One redcoat recalled afterwards how sick he felt. A friend had been shot in the stomach and lay groaning beside him on the ground and he could do nothing. To the French the men in the motionless red line seemed insensible to the fusillade they faced. The first quality of a general in chief is to have a cool head which receives exact impressions of things, which never gets heated which never allows itself to be dazzled by good or bad news. Napoleon

|

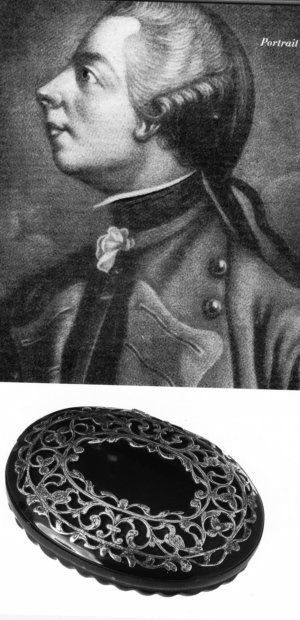

The confrontation Wolfe coveted had finally come. In the thick of combat the ailing general became a superlative soldier. Animated by the prospect of action, the tall, gawky commander was easy to identify. As though determined to die on this rolling plain, Wolfe walked up and down before his troops while French fire riddled the ranks. He was impeccably dressed in an immaculate new scarlet coat with gilt buttons, its long skirts tucked back to reveal the inner lining of blue satin. Beneath he wore a white ruffled shirt and an embroidered waistcoat girdled by a sword belt of gold thread. During the early part of the battle Wolfe wore a cloak to ward off the early morning chill. His face under the silk-edged tricorne hat was as white as the knee breeches over which were drawn gaiters that reached to mid-thigh gartered below the knee. Win, lose or draw one should look one's best. Wolfe carried a short, straight, cross-hilted sword without a guard. Known as a hanger [***] it was more suitable for travel in boats and in rough bush country than the longer parade sword.

|

|

Wolfe's Cloak |

Wolfe seemed happy, confident and anxious to fight. Earlier he had written to his mother. "As I rise in rank people will expect some considerable performances and I shall be induced in support of an ill-gotten reputation to be lavish of my life and shall probably meet that fate which is the ordinary effect of such conduct. I am ready to die gracefully and properly when the time comes."

|

A leader's charismatic power is not mere fantasy. "Radiant and elated beyond description" Wolfe's lanky figure was front and centre. He walked up and down the ranks, indifferent to danger, ignoring the sharp-shooters and exploding shells, talking to the men and nodding to the officers. He stood once more on the battlefield, excited and unafraid. All that was best in the man was there to be seen and admired. A soldier who afterwards proudly wrote that he "was standing at this precise moment of time within four feet of the General," described how happy Wolfe looked. "He was surveying the enemy with a radiant countenance joyful beyond description."

One of his captains was shot through the lungs and on recovering consciousness he saw the General standing at his side. Wolfe pressed his hand, told him not to despair, praised his bravery and promised him a promotion. He sent an aide-de-camp to Monckton to remind him to keep that promise should Wolfe himself fall. This was one of the reasons his men worshipped him. They trusted him with their lives and would have followed him anywhere.

The greater the general the more dependant he is on manoeuvre and less on loss of life. Battles that were masterpieces of military art were battles of manoeuvre in which the enemy was defeated by some novel tactic or device, some unexpected, unusual, swift thrust or stratagem. Nothing in war is more unnerving than the unexpected. In such battles losses of the winner were small.

Nevertheless, soldiers who fought under Wolfe were warned not to be in love with his life for Wolfe brooked no faintheartedness on the field of battle. When he commanded the 20th Foot at Canterbury in 1755 he warned,

In His Own Words

"A soldier who quits his rank or offers to flag is instantly to be put to death by the officer who commands that platoon. A soldier does not deserve to live who won't fight for his king and his country." Anyone who wavered was to be run through by the officer or non-commissioned officer behind him.[****]

|

|

Wolfe Among His Men [**********] |

Success on the battlefield depended on two things: firepower and discipline. Without drill there was no discipline; without discipline there was no cohesion; without cohesion, no success. Wolfe had both. His men were well trained and well armed. Each soldier carried a "Brown Bess," a more effective firearm than the French weapon. Lighter than the French musket it weighed eleven pounds two ounces and had a barrel three and a half feet long and an effective range of 75 yards. Each iron ball weighed one and a third ounces.

Sergeants moved among the men checking each weapon and ammunition - sufficient powder, ball and paper for twenty-four rounds. Each cartridge was wrapped in paper with 4.5 drams of black powder. Once every thing had been inspected orders were barked out. "Handle cartridge" This required the soldier to pull a cartridge from the pouch and bite it open with his powder-blackened teeth. "Prime" required the soldier to pour a little powder into the pan and the rest down the barrel. On the command "load,"two balls with wadding that prevented the balls from rolling out were inserted into the barrel. These charges were rammed home with a ramrod which was then replaced in its loop under the musket barrel. A bayonet was fixed to each gun. There was plenty of time. "Not a shot now, mind till they've come to forty paces." When three French cannons began to rake his ranks Wolfe ordered the men to lie down.

As the French came into range Wolfe ordered the redcoats to rise. They stood holding the tools of their trade: muskets and fixed bayonets. The first rank dropped to one knee and both ranks levelled their weapons each of which was loaded with double balls. When the French had advanced to within forty yards, the command was shouted, "Fire." Wolfe gave the order and it was repeated simultaneously all down the line. Rifles thundered to life, their combined cannonade described by one observer as the most precise ever fired on the field of battle.

The opening volley, which sounded to Montcalm and his men like a single shot, was devastating. A deep gash appeared in the French ranks. Through the thick smoke that enveloped the enemy British soldiers could hear screams of pain as bullets thudded into the phantom fighters. The shattering double volley of several thousand musket balls at close range was devastating in its precision and effect. Dense cloud of smoke shrouded the French soldieres from sight and when it cleared nearly every man in the French front rank had fallen like wheat before a sickle.

|

|

Redcoat Fusilade Fragments French Advance |

The redcoats reloaded and through the clearing smoke and chaos of bodies made their counterattack. They advanced twenty paces and fired again, the combined boom of their Besses echoing like thunder. As the white smoke slowly drifted away they could see the pandemonium they had caused. Bodies littered the landscape while other soldiers were kneeling or sitting moaning and groaning in their pain. The confused mass of dead, dying and wounded was incapable of further resistance. Beyond remnants of the regiments were wavering in the face of these booming barrages. Confused and terrified the French scattered before them.

Military historians say the shock effect of battle is rarely produced by physical conduct. Shock is communicated more by the soldier's mind than his body. Firmness and resolution will surmount any difficulty. An example of this was cited by a French officer who recalled a previous battle when "the British were completely beaten and the day was ours but they did not know it and would not run." An army's fighting esprit is not broken because its ranks are sparse or its troops are trounced, but because the soldiers are convinced that further resistance is useless. History recounts cases of regiments being routed while still possessing a 2 to 1 numerical superiority. They were not beaten; they simply believed they were beaten.

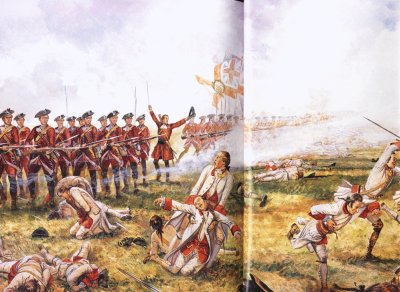

With the field littered with crumpled white coats, the soil soaking up their blood and confusion reigning round about it seemed to surviving soldiers that all was lost. Doubt and indecision swept their ranks. No sooner had they lost their order than they lost their resolve. In the midst of the mayhem fear rode their shoulders and panic ruled their ranks. Panic alone did not break their lines. Their force was not cohesive; they were not disciplined to act together, not focussed into one fighting machine. Subsequent British volleys completely shattered the French assault causing the troops to fragment into a formless mass. On the order 'Advance' the spirited, haughty, bold, bellicose redcoats charged forward with sword, claymore and bayonet brandished to complete the defeat.

The scene was now a classic and intense killing contest amid screams, blood and gore of battle. As it reached close-quarters range the last volley was fired by both sides just a dozen yards before the bayonet charge. . Military men say before attacking with the bayonet it is expected that half the enemy has been brought to the ground. In close combat British soldiers were "the very devil." Preceded always by preparatory lusty cheers which on every occasion indicated an attack, the order was given "Charge." With bayonets fixed and claymores brandished, a rampart of redcoats surged forward through the smothering, acrid gun smoke to grapple hand to hand with death. With slow steps and terrible outcry they advanced upon the enemy prepared "to hack about them until blood crimsoned the brightness of their swords and all were either dead, worn out or victorious."

|

|

Charge |

The 78th Regiment of Foot, known as the famous Fraser's Highlanders, had the tartan wraps, broadswords and pipers that had been at Culloden where some of them had fought for the Catholic Bonnie Prince Charlie. Now they were being commanded by a man who had fought against them at that bloody battle. Wolfe had suggested recruiting the Highlanders as mercenaries, noting their ferocity and fearlessness. The Highlanders, who were the fire and sword of the regiments, brought glory to Scotland that day and ever since they have marched in the vanguard of the British army. Captain Gordon Skelly, a naval officer who took part in the conflict recorded in his handwritten account that "the whole line of the enemy soon gave way, ours pushing on with their bayonets till they took to their heels and were pursued with great slaughter to the walls of the town." They fled for their lives - a mob of panic stricken men pursued "within musket shot of the walls, scarce looking behind until they got within them." "Never was a rout more complete than that of our army,"recorded one French soldier. A journal kept by the French military discloses this surprising admission. "The rout was total only among the regulars; the Canadians accustomed to fall back Indian fashion and to turn afterwards on the enemy with more confidence than before, rallied in some places and under cover of the brushwood by which they were surrounded forced divers corps to give way, but at last they were obliged to yield to the superiority of numbers."

An 18 year old Quebec militiaman later recalled this incident.

In His Own Words

"I can remember the Scotch Highlanders flying wildly after us with streaming plaids, bonnets, and large swords - like so many infuriated demons - over the brow of the hill. In their path was a wood in which we had some Indians and sharpshooters who bowled over the Scottish Savages in fine style."

At the head of the 'Scottish Savages' was Major-General James Wolfe. Cool, composed, instantly recognizable, Wolfe's spindly frame towered above the ranks as he pointed his sword, shouted commands and urged the men onward. A premonition Wolfe had prior to the battle warned it would be his last. Now as he recklessly exposed himself to the French fire he was unmindful of his rapidly approaching rendezvous with death.

The effectiveness of an attack varies in direct proportion to the conviction of victory it can instill. "Don't tell me about physical condition," said Wolfe, " a good spirit will carry a man through anything." Wolfe had a gift for leadership, a soldierly sense of duty and great moral as well as physical courage. With that spirit he inspired and infused faith in his fighting men.

A Canadian sharpshooter hit him first on the right wrist severing a tendon. It was a trifling wound and he wrapped it with his handkerchief, thrust his hand into his pocket, picked up his sword with the other hand and pressed on. He advanced to some rising ground on the right of the line and ordered a soldier named James Henderson to secure it with a few men and "Maintain it to the last extremity." A moment later he was hit again, but still kept his feet.

Henderson wrote an account of the scene to a relative in England. His letter survives, heavily creased and stained as a result of many unfoldings. "And then the Genl came to me and took his Post by me. But Oh! how can I tell, my dear Sir. Tears flow from my eyes as I write. The Great, ever memorable Man whose lose can never by enough regretted was scarce a moment with me till he received his Fatal Wound. When the Generl received the Shot full in the chest, I caut hold of him and helped him off the field. He walked about a hundred yards and then begged I would let sit down which I did. Then I opened his Breast and found his shirt full of blood at which he smiled and when he seen the distress I was in, My Dear, said he, Don't grive for me. I shall be happy in a few minutes. Take care of yourself as I see you are Wounded. But tell me how Goes the Battle. Just then came some officers who told him the French had given ground and our troops are pursuing them to the Walls of the Town. He was lying in my arms expirin. At this news he raised himself up and Smiled in my face. Now, said he, I die contented. From that instant the smile never left his Face till he Died."

|

Another contemporary version of Wolfe's final moments recounted that being asked if he would have a surgeon he replied, "It is needless; it is all over with me." For a few brief moments his consciousness seemed to come and go. He closed his eyes and appeared to be in a coma, his breathing laboured and shallow. Blood flowed freely from his wounds and the handkerchief around his wrist was as scarlet as his coat. The men about him watched helplessly in stricken silence until one of them moved to a low ridge from which he could see the battle. Suddenly, he cried out, "They run! See how they run!" Wolfe opened his eyes and attempted to rise. "Who runs?" "The enemy, Sir, Egad they give way everywhere." Turning on his side Wolfe said, "Now God be praised, I will die in peace" He had fulfilled the task destiny had assigned him. Wolfe's victory is one of the grand scenes of British imperial history, a rare battle that really did turn the tables.

When the gun smoke cleared on the fighting field that day it revealled the rout of a ruined army. Inside every army is a crowd struggling to get out and in the face of fire and steel the French forces dispersed like wisps of vapor in the morning sun. A British officer described it this way. "We advanced, they took the hint and ran away" [*****]leaving the battlefield covered with the stooped stubble of their dead and dying. The field of battle presented a frightful and most destressing spectacle. The groans of the wounded and the shrieks of the doomed were heard on every side.

British troops should have been celebrating their victory but as the news spread that their commander was mortally wounded, "our joy at this success was inexpressly damped by the loss of one of our greatest heroes." Wolfe had tirelessly paced the lines and with his familiar lean figure and bright scarlet coat was a prime target for French snipers. It is clear from letters of the troops that they loved and respected Wolfe. Having cared for his men he was loved by them and many wept unashamedly on learning of his death.

The brigadiers on the other hand had not given undivided loyalty to their commander.Their behaviour is open to censure. A commander less headstrong and less inclined to lose his temper might have found them more loyal and supportive. On the other hand a weaker leader might have been broken by their jealous disloyalty.

|

For James Wolfe, the youngest major-general in the British Army, the paths of glory had led directly to the grave. Wolfe loved these lines and quoted them to himself again and again. [******] As time dripped out its last scarlet minutes, "his valiant spirit fled." He was thirty-two years old. If he had escaped from the French musketry he would have succumbed to the galloping consumption that was already eating him away. He died as he had wished: directing his men in the hour of victory. "Nothing except a battle lost can be half so melancholy as a battle won," wrote the Duke of Wellington about the dead and dying strewn across the field of Waterloo.

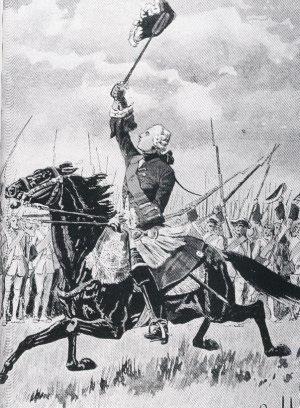

Montcalm in a vain attempt to rally his men had pressed forward fearlessly into the hail of fire. Brave Canadian snipers covered the retreat as best they could but Montcalm's offensive had petered out in mud and blood.

|

|

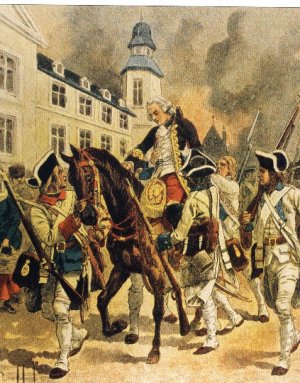

Rally Round, Men! |

Hit twice himself in close succession, the second shot passing through his body, Montcalm reeled in his saddle and would have fallen but for two grenadiers who sprang to his side to keep him mounted.

|

|

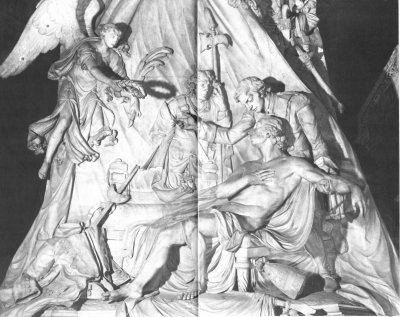

Montcalm Fatally Wounded |

|

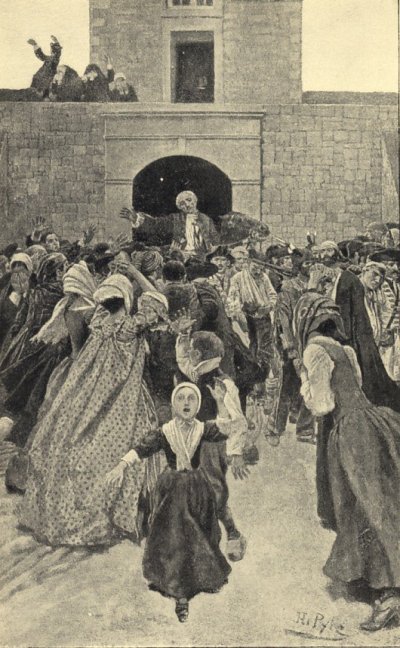

He was led back on his horse to the city through St. Louis Gate to a surgeon's house. Seeing him pass pale and covered with blood anxious onlookers cried out, "The marquis is killed." "It is nothing! It is nothing! Do not distress yourselves for me my good friends."

|

|

Woe and wailing for the Badly Wounded Montcalm |

|

An officer provided this account of Montcalm's death. When his wound was dressed, he asked the doctors what his chances were. Informed that his wounds were mortal and he had only hours to live, Montcalm responded, "I am happy I shall not live to see the surrender of Quebec." He dictated the following letter of capitulation to the British commander.

"Sir - Being obliged to surrender Quebec to your arms I have the honour to recommend our sick and wounded to Your Excellency's kindness and ask the execution of the exchange treaty agreed upon by His Most Christian Majesty and His Britannic Majesty. I beg Your Excellency to rest assured of the highest esteem and respectful consideration with which I have the honour to be, Your most humble and obedient servant, Montcalm."

After writing a message to each member of his family and saying his final farewells, he passed the night in prayer. On the 14th of September at five in the morning just as dawn was broke over the battered city of Quebec the great marquis died under the hammer of defeat. He was forty-seven. No coffin-maker could be found so an old servant of the Ursuline nuns nailed together a crude box into which the Marquis's body was laid. The burial took place at 9 that night, the rustic coffin followed by a forlorn procession of garrison officers, despondent women and confused, frightened children. By torch light Montcalm was interred under the floor in the chapel of the Ursuline convent. He lay in his soldier's grave before the humble altar of the Ursulines asleep in peace among his triumphant foe. His grave was excavated by a bursting British shell.

Montcalm's funeral was also the the funeral of the ancient regime of New France for both were buried that night. Thanks to his all-too-human blunder the engagement that lasted barely ten minutes had brought Montcalm's and France's fortunes in the new world to a shuddering halt.

"What a scene ! An army in the night dragging itself up a precipice by stumps of trees to assault a town and attack an enemy strongly entrenched and double in numbers." So wrote an English writer on learning of the battle at Quebec. News of Wolfe's victory was received in England with mixed emotions. Tears marred the merrymaking for the dauntless hero had fallen in the hour of his triumph. The young conqueror - he was only 32 - was lauded to the skies. Bonfires blazed throughout the country, the sole exception being Blackheath, where Wolfe's mother mourned the death of her famous son. Fellow citizens respected her grief and refrained from public rejoicing. A family friend wrote that Wolfe was to be lamented but not pitied. "Compassion is due only to his mother and his intended bride Katharine Lowther."

In a letter to his mother Wolfe had said his utmost desire and ambition was to look steadily upon danger and his greatest happiness would be to see her happy. He never lived to see his mother happy if "that suffering soul could ever have been capable of contentment. Henrietta was a stern mother but she loved her son and watched over his health and interests with jealous devotion. Even the knowledge of her son'e immortality could not console her. His death plunged her into darkness and she shut herself up in her house and refused to see anyone. Katherine Lowther wrote to her but she never replied. Katherine gave away Wolfe's picture and destroyed his letters and gifts. She married the Duke of Bolton six year later and lived for fifty years after Wolfe's death.

|

|

Katherine Lowther< [A portrait of Katherine Lowther "from an original pastel in the possession of Lord Londsdale." BR> |

One of Wolfe's bequests involved Miss Lowther's picture which he had carried to Canada. "I desire that Miss Lowther's Picture may be set in Jewels to the amount of five hundred Guineas and return'd to her." Mrs. Wolfe herself paid for the setting of Katherine Lowther's minature in diamonds. It was returned to her and today is displayed in Lowther Castle.

|

|

Lowther Castle |

General Wolfe's victory at Quebec is one of the grand scenes of British imperial history. It was one of the few battles that really did turn the tables. News from the four winds had brought Britain tidings of fortresses taken and battles won but none was more celebrated than Quebec's fall to Wolfe's offensive. It climaxed a "glorious year" of military miracles. The year 1759 "rained victories and wore church bells threadbare" pealing for the triumphs. "Victories come tumbling over each other from distant parts of the globe. The Romans took 300 years conquering the world. We subdued it in three campaigns." Wolfe's capture of Quebec was the brightest star in a year of victories, and is still recalled in the naval march, Heart of Oak, first heard in David Garrick's play, Harlequin's Invasion, in which Garrick sang to enraptured audiences,

Come cheer up my boys

'tis to glory we steer

To add something more to this wonderful year…

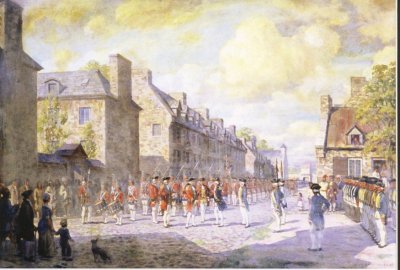

After Wolfe was killed and his second-in-command was seriously wounded British leadership unexpectedly fell to Viscount George Townshend. In one letter sent to then-British secretary of state William Pitt in England, Townshend described the battle in detail. In another dispatch he declared the outcome. "Quebec is taken after a single and complete victory over the French." Townshend also explained why he did not pursue the retreating French, contending it "was not my business to risk ye fruit of so glorious a day and to abandon so commanding a situation." Townshend apparently took pains to justify why he let most of the French army escape and granted lenient surrender terms to obtain a swift capitulation. Townshend's report on the battle also stated, "The enemy line the bushes in their front with 1500 Indians and Canadians and daresay most of their best marksmen which kept up a very hot though irregular fire upon our whole line."[*********]

Quebec had fallen but the British had a long, harsh winter ahead before Canada was indisputably in their hands. Townshend had returned to England (so his enemies said) to claim the honours of the victory. Monckton departed for New York to recover from his wound. Murray was left in an almost impossible position. When fall arrived bringing "frost and sleet," Murray prepared his troops for the severe winter behind the walls of Quebec City, much of which was heavily damaged. Murray's chief problem was to keep his men alive for scurvy was rampant. In September Murray commanded seven thousand men. By March 1760 only four thousand eight hundred were fit for duty. Over a thousand had died and the remainder were hospitalized.

|

|

British Soldiers Drawing Wood, Quebec 1760 |

|

|

Quebec City 1760 |

General Amherst assumed overall command of the British invading force after Wolfe's death. While Amherst had an unbroken record of successes, he was a solid rather than a brilliant officer. He never conducted a battle and his style was slow and heavy as the campaign of 1759 amply showed. He was a cautious, lethargic man who afforded Wolfe little help and was slow to come to the assistance of Murray who was left in charge of Quebec after the Battle of the Plains of Abraham. However, Amherst, whose manner was described as being "grave, formal and cold," was an excellent organizer who left nothing to chance as far as supplies and transport were concerned.

|

|

Jeffrey Amherst |

In Montreal meanwhile Brigadier General Francois de Levis, Montcalm's second in command, was laying plans for a spring offensive to retake Quebec. He knew chances of success were slim and that their only hope was to strike before English ships arrived with reinforcements. In April 1760 Levis engaged Murray in battle. Murray's forces totalled some 3600 against French forces numbering 7000. Murray had a stronger position until he decided to do as Montcalm had done and fight outside the walls. Anxious to outshine Wolfe with "our little army in the habit of beating the enemy," he decided to charge Levis.

|

|

General James Murray |

The drums rolled and the redcoats advanced. The plains were treacherous with snow, ice and slush which took its toll on the attackers. Precious cannon became mired in the mud and soldiers slipped and slid, falling and dropping their muskets in the wet, messy mixture. Levis's forces fell back enticing Murray's men into the knee-deep snow, all the while deadly Canadian snipers fired from behind the trees at the redcoated-targets mired the snowy depths. During the hour-long battle Murray had two horses shot from under him. When the artillery became "bogged down in deep pits of snow," Murray sounded retreat and the British retired within the fortifications with the French in hot pursuit. So ended the second battle of Quebec. Murray's mistake proved that history could repeat itself. In London the events in Quebec caused annoyance rather than shock. Canada had been conquered and now there was this annoying news that what Wolfe had won might be undone.

|

|

Murray Driven Back to Quebec |

Amherst, who was on his way from the west to attack Montreal, moved his army so slowly he was of little help in rescuing Murray from his predicament. Within the walls there was no fresh food, only tough salt pork. Scurvy swept through the garrison. Several men were shot or hanged for robbery. Men caught trying to desert were given a thousand lashes, the beat of the drum and screams of the victim pierced the grim silence of the frozen town. The British were down to a two week supply of ammunition. Both sides knew that the flag of the first ship up the river would determine the winner.

|

|

Francois de Levis |

On the morning of May 9 Murray was informed that a ship was coming round the point of the island. When it hove into view it carried "les trois couleurs anglaises." It was the British frigate Lowestoft. The English on the walls went wild. Murray and his men cheered and cheered from the ramparts. "The gladness of the garrison is not to be experienced. Officers and men mounted the parapets in the face of the enemy and huzzaed with their hats in the air for nearly an hour."

In a bitter letter to Paris Levis claimed that "one single frigate" from France would have given him Quebec and saved Canada for another year. Levis did not attend the surrender ceremonies. He was busy burning the colours of his regiment and depriving the English generals of the trophies which meant so much to a military man. The English had taken the city but it was a desolate prize. "Quebec is nothing but a shapeless mass of ruins. Confusion, disorder, pillage reign even among the inhabitants... each searches for his possessions and not finding his own seizes those of other people. English and French, all is chaos alike."

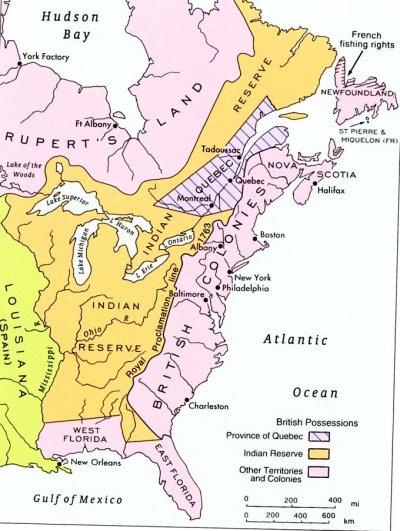

THE PINCERS CLOSE

Vaudreuil had no choice. Caught between Amherst advancing along the lower lakes and General James Murray coming up from Quebec, he could look for no further help from France. The text of Vaudreuil's capitulation ran to 55 articles. He asked for certain privileges for the Canadians: freedom of worship; freedom to enjoy their property; and the right of all to remain unmolested in their homes. This last was no mere formality for the expulsion of the Acadians must have been in the thoughts of every Canadian. All this Amherst granted. Two other requests followed: that no Canadian or Acadian should be obliged to take up arms against the French king and that Canadians should continue to enjoy their customary law. To these requests Amherst made a terse reply. "They become Subjects of the King." No other response could have been made in the circumstances.

Articles of Capitulation Between His Excellency General Amherst, Commander in Chief of His Britannic Majesty's Troops and His Excellency The Marquis De Vaudreuil, Governor and Lieutenant General for the King in Canada

|

|

Vaudreuil and Amherst |

Article I "Twenty-four hours after the signing of the present capitulation, the English general shall cause the troops of his Britainic majesty to take possession of the gates of the town of Montreal and the English garrison shall not come into the palce till after the French troops have evacuated it. Immediately after the signing of the present capitulation, the king's troops shall take possession of the gates and shall post the guards necessary to preserve good order in the town."Vaudreuil was fortunate to escape unharmed for earlier an Englishman had said of him, "Had he falled into our hands our men were determined to scalp him, he having been the chief and blackest author of the cruelties exercised on our countrymen."

By the 55 articles of capitulation "done in the camp before Montreal the 8th of September, 1760" by Vaudreuil and Amherst, Britain received half a continent: Canada as well as all the lands and waters to the west that Champlain had dreamed of and that the great explorers had seen but never settled. Canada passed into the possession of the British crown conquered by Wolfe on the Plains of Abraham and by Murray's stubborn defence of Quebec. /p>

|

|

Fench Surrender at Montreal 1760 |

|

|

France Surrenders to England (In the background Quebec is portrayed.)(NAC) |

|

|

Treaty of Paris 1763 |

Wolfe was not buried on the field of honour nor even in the country he conquered. His body was carried off the field in a cloak that is now preserved in the Tower of London and according to the ship's log, he was taken aboard HMS Lowestoft. "At 11.00 a.m.was brought on board the corpse of General Wolfe." The body was removed to Point Levy where it was embalmed. Late in October as the fleet set sail for England, cannons on the ramparts of Quebec responded to the naval salute of the departing ships.

|

On board the Royal William lay the body of General James Wolfe. It was attended by Captain Thomas Bell, an aide-de-camp, who said he, "accompanied our noble master to the Grave."

The body arrived at Portsmouth on November 18th. "Saturday morning at seven o'clock, his Majesty's ship the Royal William fired two signal guns for the removal of the remains of the ever to be lamented General Wolfe. At eight o'clock, the body was lowered out of the ship into a twelve-oared barge, towed by two twelve-oared barges and attended by 12 twelve-oared barges to the bottom of the point in a train of gloomy, silent pomp, suitable to the melancholy occasion, grief shutting the lips of the fourteen barges' crew. Minute guns were fired from the ships at Spithead from the time of the body's leaving the ship to its being landed at the point which was one hour. A troop marched to the bottom of the point to receive th gallant remains. Bells were muffled and rung in dismal solemn concert with the march as minute guns were fired at the entrance of the corpse. Although many thousands were assembled for the occasion, not the least disturbance happened. Nothing was heard but moans and murmurings broken by accents of praise for their dead hero. Wolfe was interred privately in the family vault at St.Alfege church Greenwich on the following Tuesday between seven and eight o'clock at night beside his father who had died in March of the same year." Wolfe's mother was subsequently buried there in September, 1764.

There is a statue of Wolfe in Greenwich Park on the hill near the Observatory. It was unveiled in 1930 by the Marquis of Montcalm. During the World War II the monument's white plinth was pitted by a bomb blast.

In the Westerham church the following epitaph was chiselled on a monument.

Whilst George in sorrow bows his laurell'd head

And bids the Artist grace the Soldier dead,

We raise no sculptured trophy to thy name

Brave youth! the fairest in the list of fame:

Proud of thy birth, we boast th' auspicious year,

Struck with they fall, we shed a general tear;

With humble grief inscribe one artless stone,

And from thy matchless honours date our own.

As a result of a miscalculation in his will, [*******] Wolfe bequeathed some 2000 pounds more than his estate contained. Demands were made that the government make up the difference but it never did. All Wolfe's other legacies were included by Mrs. Wolfe in her own will. When the George III learned of the taking of Quebec, he said to Pitt, "All your plans have succeeded. Quebec is certainly a great acquisition but 'tis bought too dear. Wolfe is an irreparable loss, such an head, such an heart, such a temper and such an arm are not easily to be found again." While the king lauded Wolfe and Pitt praised him in Parliament neither was prepared despite various appeals for funds by Wolfe's mother to put money where their mouth was. George III ignored her pleas; his father, George II would immediately have remembered her son's services.

On November 22nd, 1759 it was announced that "The thanks of the Honourable House of Commons will be given to all the Officers that were at the taking of Quebec. And it has also been unanimously resolved that a monument be erected to te memory of the late General Wolfe." Despite this committment many felt the government was slow in honouring Wolfe. Although enormous amounts had been voted by Parliament to commanding generals in comparable victories, Wolfe received just the thanks and the promise of a monument from the House. It was only after public pressure was exerted that funds were voted for what some consider a pretentious edifice finally unveiled in 1773 in Westminster Abby.In the report sent to England by the brigadiers, no valediction of any sort was directed to the memory of the dead leader as had been done when Nelson fell at Trafalgar. The tribute on that occasion moved the whole nation and even caused verbose George III to pause in respectful silence. This glaring omission was rectified by some unknown scribe who provided the following tender tribute.

Underneath a Hero lies

Wolfe the Young, the Brave, the Wise:

No Tombstone need his Worth proclaim

Quebec forever shall record his Fame;

Quebec forever shall with Wonder tell

How great beneath her Walls, her Conqueror fell.

|

|

Westminster Abbey - House of Worship, Home of Heroes |

|

|

Wolfe's monument in Westminster Abbey |

|

|

|

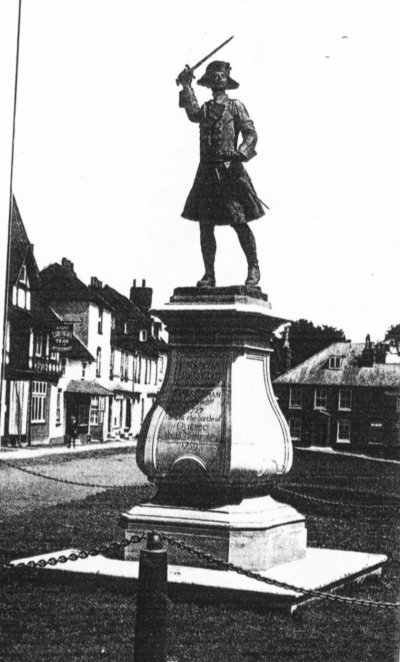

Wolfe in Westerham |

|

|

Wolfe in Westerham |

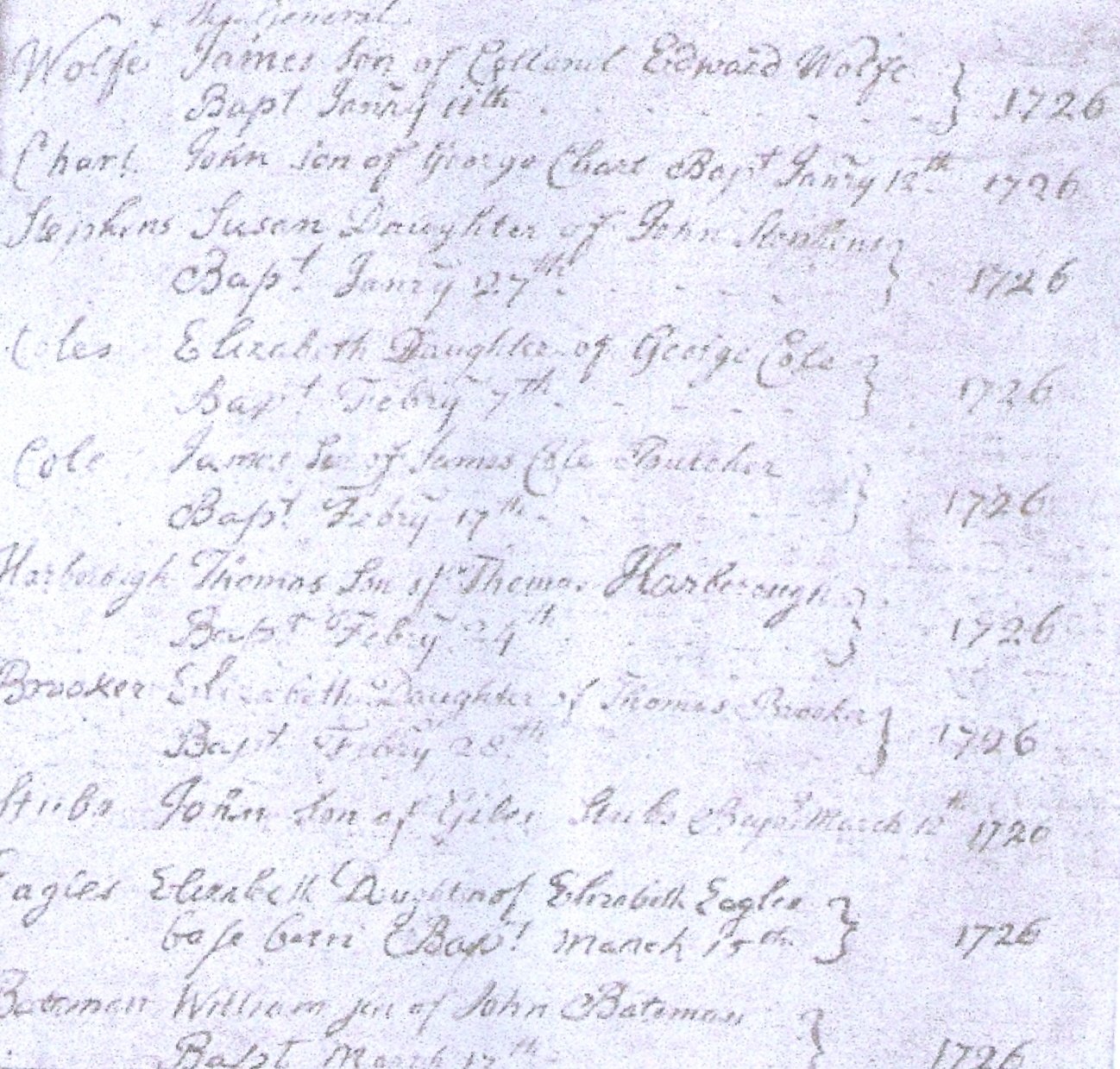

Some in the parish of Westerham in Kent erected a plain monument to the late General Wolfe. The table of statuary marble with white letters inlaid in a ground of black marble was executed by Mr. Lovel near Cavendish-square.

James

Son of Col. Edward Wolfe and Henrietta (his wife)

Was born in this Parish, January the 2nd, MDCCXXVII

|

|

Wolfe's Baptismal Certificate |

>

And Died in America, September the 13th, MDCCLIX

Whilst George in Sorrow bows his Laurel'D head,

And bids the artist grace the soldier dead:

We raise no sculptur'd trophy to thy name,

Proud of thy birth, we boast th' auspicious Year,

Struck with thy fall, We shed a general tear:

With humble grief inscribe one artless stone,

And from they Matchless Honours Date Our Own.

DECUS NOSTRUM (Our Glory)

|

|

A Youthful James Wolfe |

Westerham, Wolfe's birthplace, did not forget its famous son. His former home where he spent his childhood is known as Quebec House, a National Trust property. General Wolfe spent his first eleven years in this gabled, red-brick, 17th century house. The low-ceilinged, panelled rooms contain memorabilia relating to his family and career and the Tudor stable block houses an exhibition about the Battle of Quebec. The drawing room contains William & Mary and Queen Anne pieces. Mementoes include Wolfe's travelling canteen which gives a glimpse of the comforts enjoyed by an officer on campaign in the mid-18th century. Clearly the finer things in life were not entirely discarded, as the canteen contains a cruet and glass decanters as well as more mundane objects. The finely quilted dressing gown in which Wolfe's body was returned to England from Quebec is also kept at the house.

An annual dinner honouring Wolfe's birth is held at Quebec House in November as the weather in early January (his birthday is the 2nd) is often inclement. The private dinner is presided over by the President of The Wolfe Society Squerreys Court, Westerham, Kent, UK. An impressive statue of Westerham's distinguished son is situated prominently in the town square. Wolfe shares this honour with another of Westerham's illustrious citizens, Winston Churchill, whose pugnacious pose graces the same square.

|

|

Quebec House in Westerham |

Nor did France fail to honour her illustrious son, Montcalm. When Louis XIV and his ministers learned of the loss of Quebec they refused to blame the French army or Montcalm and quickly compensated his widow with a pension. Years later even the Revolutionaries respected his name. In those fateful days during the French Revolution when chaos wracked the country and the guillotine ran red with the blood of aristocrats, the republican leaders quickly eliminated the payment of any largess to all lords but one - Montcalm. This was a remarkable tribute to the man and his memory.

|

|

|

Peace on the Plains of Abraham |

|

|

The Plains of Abraham Today |

In a moving ceremony in September 2001 two hundred and forty-two years after Montcalm was mortally wounded on the Plains of Abraham, the great general was removed from his solitary grave and reburied among his troops. The remains of the Marquis de Montcalm were relocated from the isolation of the convent to a place of honour among the troops he commanded in one of Canada's most pivotal battles. The cemetery of the Quebec General Hospital is where hundreds of soldiers - both British and Montcalm's French troops - were buried in a mass grave. Montcalm's simple brown casket covered with a white French flag was borne on a carriage drawn through historic Old Quebec. It was accompanied by a military honour guard dressed in period uniforms and carrying regimental flags for each of the units commanded by Montcalm. A number of dignitaries also marched in the two-block-long procession to the cemetery which contains more than 1,000 French and British soldiers who died in the battle on Sept. 13, 1759. Granite markers will be erected at the location to memorialize the location. A military chaplain commented, "Finally Montcalm has joined the troops with whom he rightfully belongs."

|

Montcalm's remains - comprising only a skull and a leg bone - were placed in a grey stone crypt with a plaque commemorating him. Members of the Montcalm family including Guy Bertrand Marquis de Montcalm and his wife attended the ceremony. "We're enchanted and proud to come and commemorate this," said Montcalm, a direct descendant of the general who flew over from France for the occasion. "But what's extraordinary is that we're commemorating the memory of a loser. It was General James Wolfe that won. I think we should do the same for him."

Quebec's Premier Bernard Landry paid tribute to Montcalm and the 500,000 soldiers who died in the seven-year war fought between 1755 and 1762. He described the conflict as "truly the first world war. [********] We commemorate a war which brutally changed the course of our collective destiny and the entire North American continent.", Landry said that in remembering the slain soldiers and their leader, particularly in the troubling weeks that followed the terrorist attacks in the United States, the world must rededicate itself to peace.

The cemetery where Montcalm's remains now lie was designated a national historic site in 1999. The relocation of Montcalm's bones from the private crypt in the chapel of the Ursulines of Quebec convent was spearheaded by a Montreal historian, aided by the Quebec national capital commission and municipal authorities. The historic move was completed by September to mark the anniversary of Montcalm's death.

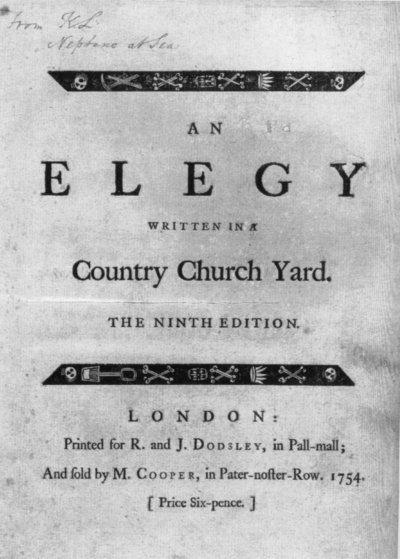

[*] The advantage of the two-man deep line over the French column permitted more muskets to be used thus maximizing the firepower. The British also practised with real ammunition and this ensured more accuracy and greater efficiency in battle. British muskets fired higher-calibre balls giving them more stopping power per shot. [**] 1759: The Year Britain Became Master of The World by Frank McLynn [***] The hanger Wolfe carried into battle that day is preserved in an English military museum. [****] There are no recorded instances of British officers applying this deadly driving force. [*****] When the Duke of Wellington was once asked by a woman whether British soldiers ever ran away, he answered, " Madam, all soldiers run away." [******] Thomas Gray's Elegy Written In A Country Churchyard.This is a popular 18th century poem about mortality, which Wolfe liked because it matched his own morose, moody nature. In the small, leather-bound volume his fiancee Katherine Lowther had given him that spring before he set sail for Canada, Wolfe had underlined the following lines.

The boast of heraldry, the pomp of power,

And all that beauty and wealth e'er gave,

Await alike the inevitable hour,

The paths of glory lead but to the grave.

|

|

Copy of Gray's Elegy Given to Wolfe by Katharine Lowther |

On the top left hand corner of the book, Wolfe had also written:

From K.L. Neptune at Sea

Legend has it that as he and his troops floated downstream towards Wolfe's Cove, Wolfe softly recited this verse to his officers. He is supposed to have said: "I would rather be the author of that piece than take Quebec." While this lends a romantic touch to the tale, there is understandably a great deal of doubt about the truth of this anecdote despite it having been carefully researched by a historian. He declared its truth had been proved "as conclusively as human testimony can prove anything." While Wolfe might very well, as he drifted along, mused on the military laurels that death and glory could bring, most historians scoff at the very thought that a commander would recite poetry in the face of the daring, dangerous mission about to be carried out almost under the eyes of the enemy.

"The anecdote has been traced to John Robison, a young man who sailed with Wolfe, but did not take part in the fighting. Robison, was an esteemed professor of philosophy at Edinburgh University, where he became acquainted with the novelist, Sir Walter Scott. One one occasion he regaled Scott with a version of the story of Wolfe and Gray's Elegy. Scott, who rarely let facts get in the way of a good story, spread the yarn far and wide and it was soon picked up by historians eager to glorify Wolfe's death as noble self-sacrifice in the larger cause of painting the globe pink." [Quoted from The Museum Called Canada, 25 Rooms of Wonder, by Charlotte Gray, publisher Random HOuse of Canada, 2004

Wolfe underlined another line in the poem:

A youth to fortune and to fame unknown.

In the margin beside this line, Wolfe queried: "Yet were he on this score less happy?"Wolfe wrote no other remarks in the book on the coming battle, although he could have since only six of the thirty-three cream-coloured vellum pages are occupied by the poem.

Miss Lowther later married a duke and became the Duchess of Bolton.

According to an article in the London Times on 15 January, 1913, this book was found in Paris with the following inscription therein.

"Given to my mother, Mrs. J. Ewing, by her mistress, the late Duchess of Bolton, as having belonged to the celebrated General Wolfe."

On the title page is a further inscription:

"From K.L. Neptune at Sea."

Facsimile of Wolfe's Will

-I desire that Miss Lowther's Picture may be set in Jewels to the amount of five Hundred Guineas and return'd to her.

- I leave to Col. Oughton, Col.Carleton, Col. Howe, & Col. Ward a thousand pounds each.

- I desire Admiral Saunders to accept of my light service of Plate in remembrance of his Guest.

- My Camp Equipage, Kitchen Furniture, Table Linnen, Wine & provisions, I leave to the Officer who succeeds me in the Command.

- All my Books and Papers both here and in England, I leave. to Col. Carleton.

- I leave Major Barre, Capt. Delaune, Capt. Smyth, Capt. Bell, Capt. Lesslie & Capt. Calwall each a hundred Guineas, and my swords & rings in remembrance of their Friend.

- My Servant Francois shall have one half of my Cloaths & Linnen here, and the three Foot-men shall divide the rest amongst them.

- All the Servants shall be paid their year's Wages, and their board Wages till they arrive in England or till they engage with other Masters, or enter into some other profession. Besides this, I leave fifty Guineas to Francois, twenty to Ambrose, and ten each to the others.

- Every thing over and above these Legacies, I leave to my good mother entirely at her Disposal. JAM.Wolfe

Witesses-

Will Delaune

Tho Belle

|

|

Wolfe's Tobacco Box |

[********]

The fighting on the Plains of Abraham was one battle in the Seven Years War. (1756-63) The war, which Churchill called the first world war, was fought around the world between France, Austria, Russia, Saxony, Sweden and Spain against Prussia, Britain and Hanover. Under the Treaty of Paris in 1763, France gave Canada to Britain, but got back the islands of St-Pierre and Miquelon. These tiny islands,which are still French territory, are south of Newfoundland.

[*********]CBC on Sunday, December 11, 2005Canadian History Up For Grabs

It was reported by the that the Plains of Abraham letters are up for auction. A piece of Canadian history goes on the auction block at Christie's in New York this Thursday They are Townshend's letters about the British victory over the French during the 1759 battle on the Plains of Abraham. On its website the auction house says Townshend apparently took pains to justify why he let most of the French army escape and granted lenient surrender terms to obtain a swift capitulation.

[**********] Globe and Mail, May 25, 2007Wolfe the Dauntless Hero

Wolfe is Canada's most mythologized man and the 250-year old painting that triggered General James Wolfe's transformation into a national icon has emerged from obscurity in Britain to be sold next month at auction. Long thought lost, the small oil portrait shows the ill-fated victor of the Plains of Abraham striking a heroic pose while his troops scramble up the cliffs outside Quebec City to vanquish General Montcalm and seize Canada for the British. Painted within months of his death, it was soon being re-produced in magazines, posters and books, fueling a cottage industry of printed memorials to the fallen general throughtout the British Empire.... It is considered one of the few known images to have captured Wolfe's true appearance around 1759, since is was believed to have been based on an eyewitness sketch by Hervey Smyth, the general's aide de camp in Canada. It is expected to draw bids of up to $175,000, because its value is enhanced by its important early provenance' among descendants of Lieut.Col. Henry Fletcher, who fought at Wolfe's side in Canada.

|

|

James Wolfe |

Fast foward 250 years to 2009.

On the 250th anniversary of the great battle, the decision was made to herald this important event in our nation's history by re-enacting on the Plains of Abraham for us the most significant battle during the Seven Years' War. Despite the passage of two and a half centuries, it quickly became evident that feelings are still fresh and tempers still taught about this event so central to the creation of this country. The proposal to don the white and the red and redo the fight on the same field where the conflict was fought that September day in 1759, has been met with outrage and anger by some who still see shame in the outcome. Those wishing to highlight the history on the Heights, decry the bitter behaviour that they believe lingers long after it should have disappeared. The raucous rejection by a few of this replay, represents for many, a lamentable loss of an opportunity to highlight the history that makes us who we are.

OTTAWA, Feb. 25, 2009

The man at the centre of a controversy regarding a cancelled re-enactment of a 250-year-old battle between British and French troops in Quebec City received a rude welcome as he appeared Wednesday at parliamentary hearings. The Bloc Québécois greeted André Juneau, chairman of the National Battlefields commission, with calls for his resignation. Bloc heritage critic Carole Lavalée said Mr. Juneau showed poor judgment in organizing a re-enactment of the 1759 Battle of the Plains of Abraham -- which sparked anger from Quebec nationalists. She also expressed concerns about money the commission received from the former Liberal government as a part of its sponsorship program to promote Canadian unity. "I sincerely believe what we're seeing today is the debris left over from the sponsorship scandal," said Lavalee.

Liberals and New Democrats also criticized Mr. Juneau for organizing the re-enactment."It wasn't the idea of the century," said Liberal MP Pablo Rodriguez. But Mr. Juneau, who is a volunteer, insisted the federal agency never intended to "celebrate" the battle. " "I don't need to give my resignation," he told the House of Commons heritage committee. He added the commission received more than 150 threats of violence or disruptions that forced him to cancel the summer event, marking the French defeat. But said criticism and lack of support from politicians, including Quebec Premier Jean Charest, were also an important factor in the decision.

The Bloc also criticized Mr. Juneau over a guided tour program his agency offers for elementary school field trips to the Plains of Abraham. But Mr. Juneau accused the Bloc of playing politics on the backs of children, noting the educational program was in place through co-operation with the Quebec government since 1992, serving nearly 200,000 students. The Parti Québécois was in power in Quebec from 1994 to 2003.

At times, the parliamentary committee meeting erupted into a free-for-all of shouting between Bloc and Conservative MPs, who accused each other of feeding into the controversy. Conservative MP Pierre Poilievre singled out the Bloc for running advertising in a newspaper that "made racist declarations." The PQ and the Bloc have both distanced themselves from the Quebec nationalist newspaper in question, le Québécois.

Following the meeting, Mr. Juneau said he would be prepared to resign if the government asks him to do so, but Mr. Poilievre said the agency's chairman should not be forced to leave because of threats of violence made by other people.

CBCWednesday, February 25, 2009 | Plains of Abraham boss willing to resign over battle flap

The federal bureaucrat responsible for the Plains of Abraham says he's prepared to resign over a battle re-enactment controversy, but only if the government asks him to leave. Andre Juneau said Wednesday he will not quit as head of the National Battlefields Commission just because sovereigntist politicians are asking him to. Juneau was forced to cancel a planned summer re-enactment of the 1759 Plains of Abraham battle at Quebec City, which led to the fall of New France.

The embattled battlefield boss received a grilling at a House of Commons committee Wednesday where Bloc Québécois MPs asked for his resignation. He replied he would resign at the request of Heritage Minister James Moore, but not at the Bloc's behest. "I won't resign because the Bloc is asking for it," Juneau said after the committee hearing. "I've written to the minister. If the minister asks me to leave for reasons he judges appropriate, it will be my pleasure to reply, 'yes,' to his request."

Moore's office confirmed it received the letter but a spokeswoman for the minister said Juneau's dismissal "hasn't been discussed." Juneau said it wasn't just the public outcry and threats of violence that prompted the cancellation, but also the realization that politicians weren't willing to stick up for the event. Juneau said that he received 150 threatening letters over the planned re-enactment and that he turned them over to the Quebec City police. The police deemed two of the alleged threats serious enough to warrant an investigation. Juneau said the police could not have ensured the safety of visiting participants, especially as they wandered around Quebec City tourist attractions away from the re-enactment site.

While the controversy brewed, a variety of federalist politicians, including Premier Jean Charest and some cabinet ministers in Ottawa, declared they would steer clear of the event. Juneau said that lack of political support made the cancellation inevitable. He said the emotional wounds from the conquest of New France appeared wide open for some people, even after 250 years. "It's fresher than we thought," Juneau said. "But not for everybody. Not for a majority of people. A lot of people are pretty happy with what they are, as French-speaking Canadians." The federalist parties did not call for Juneau's resignation.

However, New Democrat MP Tom Mulcair called it an error in judgment for the federal government to get involved in re-enacting the event, one commonly seen by francophone Quebecers as a historic tragedy. The Conservatives appeared particularly eager to lay blame for the debacle at the feet of the Bloc Québécois. They noted that the Bloc and its provincial cousin, the Parti Québécois, are the biggest advertisers in a sovereigntist newsletter that raised the prospect of violence if the event went ahead. Conservative MP Pierre Poilievre made the link repeatedly, accusing the Bloc Quebécois again and again of "financing" a newspaper that endorses violence and racism. The accusation had Bloc MPs leaping to their feet and sputtering in rage at Poilievre's attack, with one of them swearing loudly enough to be heard from the back corner of the committee room.

The EconomistFeb 26th 2009

Fighting old battles

A 250-year-old defeat still rankles

THE Battle of the Plains of Abraham was brief and not all that bloody, but it was historic. On September 13th 1759, France's loss of its colonial territories in North America was set in motion when British redcoats scaled cliffs protecting Quebec City and defeated troops and militia loyal to Louis XV. A modern-day battle over the battle, which concluded on February 17th, lasted somewhat longer and ended very differently. It flared up over plans to mark the battle's 250th anniversary with a re-enactment, and ended with Quebec separatists crying victory and Canada's federal government beating a hasty retreat. The re-enactment was to have been the centrepiece of a summer-long commemoration of 1759's events. But to some Quebeckers commemoration sounded like celebration. "Dancing on the graves of our ancestors," was how the Réseau de Résistance du Québécois (RRQ), a group of sovereigntist hardliners, described it. They demanded the re-enactment's cancellation. For several weeks debate raged. The re-enactment was an exercise to pay tribute to the fallen and educate the living about one of Canada's most important episodes, said its supporters. These included 2,000 or so mostly American "re-enacters", the federal government and Quebec City's mayor, who was loth to lose millions of dollars in tourist spending.

Opponents, and most of the French-language press, cursed the proposed re-enactment as a "repugnant federalist propaganda operation". When it reached a point where its organisers were receiving threats-including having "our bayonets shoved up our butts", according to their leader-the National Battlefields Commission, which administers the Plains of Abraham, cancelled the mock battle and other activities planned for the summer. Or, as the Gazette, Quebec's only English daily, wrote, it "cravenly surrendered the field". If there was an edifying component to the brouhaha, it lay in displaying the different light in which the Conquest, as it is known, is seen by those on opposite sides of the Quebec independence debate. For many sovereigntists it was the beginning of domination by the wretched English, and of the struggle for cultural survival. Federalists, however, both Francophone and Anglophone, argue that after the Conquest the French of New France got rights they could only dream of under the exploitative, authoritarian ancien régime. Whatever the case, the re-enactment was probably doomed from the moment in mid-January when the RRQ pledged "to go on the warpath" against it". Support for Quebec's sovereignty spikes whenever it is felt that English Canada is taking it for granted or not respecting it. Wise federal politicians are thus wary of anything that may rile Quebec sensitivities. Nevertheless, a few cabinet ministers took opposing positions on the re-enactment

.Quebec's premier, Jean Charest, was shrewd enough not to get involved. He simply announced that he would not attend. This is a decision Generals Wolfe and Montcalm, the commanders of the British and French forces in 1759, should probably also have made; both died of wounds suffered on the Plains of Abraham.

Copyright © 2013 Website Administrator