foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

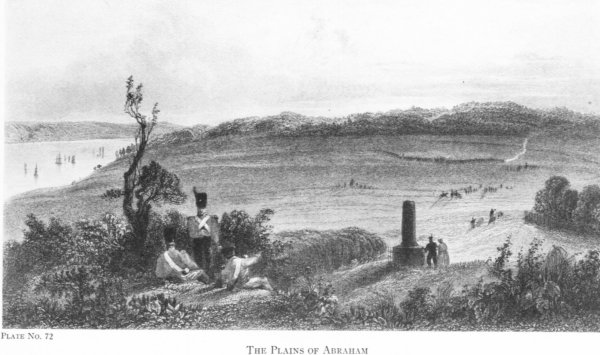

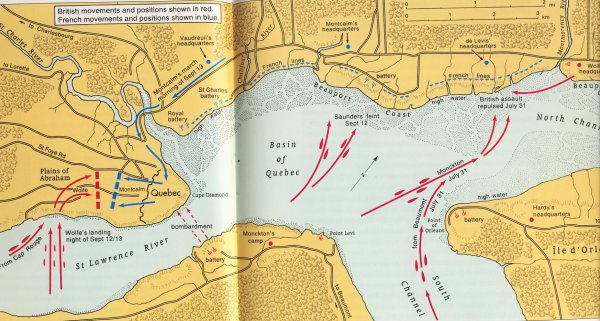

ABRAHAM MARTIN'S FARM

History is an argument without end.

|

|

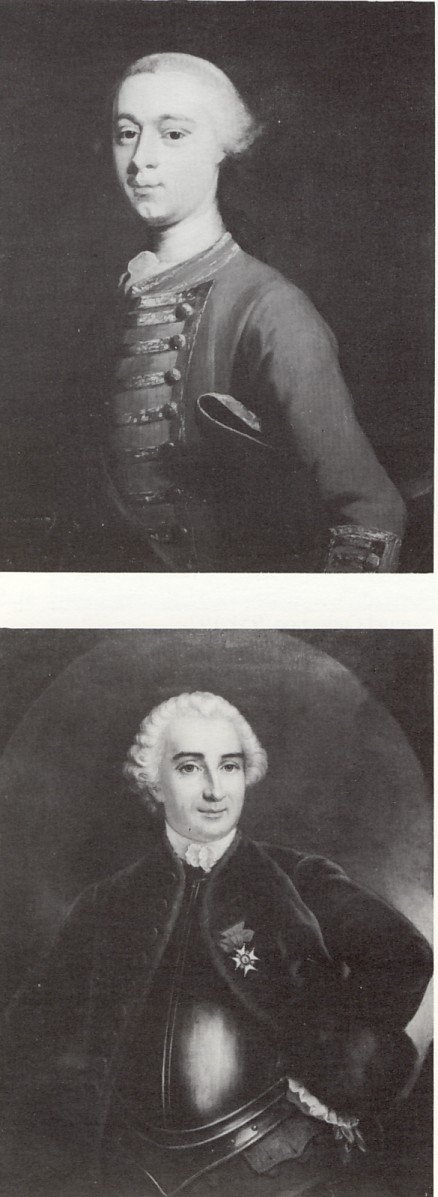

The Protagonists: |

|

In the tense times during that grim, deadly struggle, the hour demanded daring, skill, and imagination. A great commander may be epoch-making by the decision he makes and the direction he gives the forces at his disposal. Wolfe was such a leader. His intellect, energy and efficiency won the confidence of those he served and those he led. His will, one might even say his whim, made a profound difference in history. By dawn on that overcast day Wolfe had 4400 men on the Plains of Abraham, a thousand yards from the citadel's walls. They were drawn up along the crest of the heights. While Wolfe had successfully achieved a critical part of the perilous endeavour, his forces faced imminent danger. If overwhelmed by a combined attack by the Quebec garrison on one side and the French forces to the west on the other, retreat would be impossible.

Now that he was close to combat Wolfe's audacious spirit prevailed over doubt and discomfort. He pondered his good fortune. The last few hours had in themselves been a lifetime. So much had happened faultlessly. One could conceive a plan, run through it over and over again, studying and revising the minutest detail only to have a trifling mistake convert it all into chaos. On this occasion the execution was flawless; almost too good to be true. Motivated by the belief that a few good men of resolution could accomplish miracles against a surprised and shocked enemy, Wolfe proceeded to implement his "desperate plan."

While Murray, Monckton and Townshend reviewed the troops to ensure all was in order, Wolfe searched for a suitable site for the fight. Accompanied by this ADCs (aides de camp), who were his means of conveying orders, Wolfe made a reconnaissance towards the city to decide on the best location to set up. He needed open ground for deployment. It was there in front of him between, a tract of land not more than a thousand yards from the western walls of the fortress. It was ideal for his regulars and with its contours afforded some cover. It was a mile wide, fairly flat and studded here and there with corn stalks and bushes. To his right was the river; that flank was secure. In the distance the fort of Quebec itself was dark and low on the horizon. To his left across a rolling plain a line of trees marked the edge of the wilderness. That flank was the danger zone. The woods and shrub gave cover for Canadiens and Natives, exactly the kind of terrain they were best suited for and they lost no time in taking advantage of it, beginning at an early hour to harrass the redcoats.

|

|

Abraham Martin (portrayed by artist Charles Huot in 1908) |

The land had belonged to Abraham Martin, a navigator known as the king's pilot who knew the river waters well for he had frequently fished there and in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. In 1635 in return for his services, Martin had been granted 12 acres on the outskirts of Quebec and ten years later received an additional 20 acres as a gift. In 1667 Abraham sold the land to the Ursulines religious order. Chance had chosen this rustic spot, this peaceful patch of a farmer's field which became that day a giant stage on which the fortunes of war would decide the fate of two nations. At the same time Wolfe selected the site of the most famous battle in Canadian history, he decided also on the date of his death.

|

|

The Plains of Abraham |

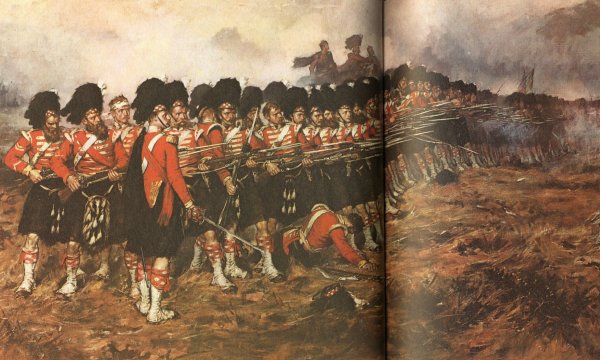

There at right angles to the river, Wolfe formed his troops into the classic 18th century line of battle across the mile width of the plain facing the city, two riflemen deep in what must have been the thinnest red lines in British military history.[*] Earlier British practice was to form soldiers into ranks three men deep. In this instance they were two men deep, the rear rank a pace behind the front. Wolfe's two-deep formation permitted the rear rank to fire over the shoulders of the men in front.It became the famed 'thin red line' of British military history. The fact not the phrase was Wolfe's.

What Wolfe lacked as a military planner, he more than made up for as a regimental field officer. Military morale results from a combination of belief in a cause, good training, trust in leadership, pride in unit, a sense of being treated fairly, belonging to a group and not letting one's buddies down, and officers who attempt to ensure that the aims of the group are congruent with those of the army. The troops admired Wolfe's own serene oonfidence which quickly spread to the troops. He displayed spirit, dash, discipline and determination. Their training and morale were excellent and Wolfe's impressive sense of authority was reassuring to the men he led. That was the beauty of soldiering with Wolfe: a man knew where he stood. He treated the common soldier as an individual with a mind, and supplied facts to keep it busy. Soldiers divided their officers into two groups: those who led and those who followed. Wolfe, a natural leader of men, was always in the forefront.

The seasoned soldiers, tough, flexible shock-troops of the empire, stood motionless not a mile from the main town gate, their red ranks at ease with rifle butts grounded at the boot. At long last after the weary journey to Canada they were poised and ready to fight the French on their own terms. If they maintained fire discipline, what Wolfe had preached all his professional life, the result of the encounter would be swift and decisive. Townshend commanded the left flank, Murray the centre and Monckton the right. Wolfe posted himself at the front of the Louisbourg Grenadiers on the right flank.

|

|

Four of the battalions wore the uniform common to the army's regular line regiments. One company in each battalion known as the Grenadier Company was composed of the tallest, strongest men. Originally they had been chosen to throw an explosive device called a grenade, a small iron bomb with an ignited fuse. The brimless hats they wore, which permitted easier throwing, became high, conical, yellow caps with a tufe at the peak.

|

They were decorated in front with a crown and the royal monogram G.R. Beneath it and immediately above the brow was the figure of a running white horse on a red background. Although this type of grenade bomb became obsolete in 1774, the grenadiers remained as a picked corps of fine fighting men. Wolfe grouped the grenadier companies of the various regiments into one separate battalion.

The line regiments wore white wigs and stiff, black, three-cornered hats with black cockades on the side like a badge. All had white knee breeches and stiff pipe-clayed belts and gaiters. The long gaiters that came over the knees were also white. Their long-tailed red coats were turned back to reveal yellow, buff or blue facings. The Fraser Highlanders had lofty, tam-o-shanter-type Scotch bonnets with a curly feather on the left side.

|

|

Highlanders' Thin Red Line |

|

|

A Highlander |

Their scarlet coats were faced with yellow. The Fraser plaid that hung from the shoulder caught up loopwise on both hips. Their kilts were short and un-pleated. They wore red and white diced hose and buckled brogues. Each was armed with a basket-hilted sword as well as a musket. In addition to the usual infantry weapons, the men carried stiff black leather pouches in front of their belts containing the latest type of grenade - small cannon balls or bombs with fuses attached which they lit and threw as they surged forward.

|

|

A Dragoon, Light Squadron 1757 (left) & A Grenadier, Regiment of Foot 1759 |

|

"Come, each death-dealing dog who dares venture his neck,

Come follow the hero who goes to Quebec.

Ye that love fighting shall soon have enough,

Wolfe commands us my boys, we shall soon give them Hot Stuff."

Montcalm meanwhile was unaware of Wolfe's threat to his position. He had passed a troubled night. It was six-thirty in the morning before he learned of the magnitude of what had transpired earlier. A messanger galloped up with news of the English landing. At first he refused to believe it, supposing the assault above the town to be a feint by a few hundred men. Discrediting reports that enemy troops in force had reached the height, he galloped to a crest of land to see for himself. As the astonishing sight greeted his disbelieving eyes dread darkened his features.

Where a scant eight hours before one saw nothing but an empty farmer's field, there not a mile distant stood thousands of British soldiers, their scarlet uniforms like bright beacons in the mist. A long, thin, red gash stretched across the plains, their rifles at the ready. Redcoats stood motionless beneath a grey sky, ready, it seemed, for a review. As the Highlanders pipers produced their first dirge-like skirls, the force across the field gave every indication, they were more than ready for white regiments to come.

Montcalm had failed the first military maxim: taking measures to ensure against surprise. "C'est serieux," he said to an aide. "They are where they have no business to be. After dispatching orders to bring up every French regular and most of the militia, he turned and without a word prepared to confront the crisis. It never occurred to him that moving fast - initiating the attack - could very well put him at a disadvantage. By doing so, he limited his options. Better to have waited for Wolfe make the first move. By initiating the assault, Montcalm awarded Wolfe yet another critical advantage. The first was allowing him to land his forces unopposed in the night.

The critical elements in war are speed and adaptability. Great leaders must be able to adapt to the changing circumstances. Montcalm failed this fundamental. Impatient to a fault he saw no necessity to adhere to defensive warfare. In his destructively self-defeating pride he made a disastrous decision. Instead of remaining behind the massive walls of his fortress he summoned his soldiers to prepare to confront the British on the field of battle. He was allowing his strategy to be made by Wolfe.

We often give our rivals the means of our own destruction. Aesop

Within the walls of the city citizens were awakened by the breathless cry, "The English are at the gates." French forces thronged through the narrow streets, pouring forth from the city with flags flying and drums beating. By nine o'clock in the morning Montcalm had some 4500 men mustered on the high plateau west of the town in front of the walled city. His army comprised battalions of white-uniformed regulars in black hats and gaiters and grey-clad throngs of Canadian militiamen.

|

|

French Soldiers Assembling |

While the ranks of his regulars were swelled by incorporating militiamen, the training and tactics of the latter made the increase in numbers a doubtful blessing. Before them stretched the open plain, a virtual parade ground on which a pitched battle calling for a highly disciplined fighting force was to be fought. Montcalm's motley mix - which also included Native warriors wild in their war-paint - failed to qualify. Previous successes of the brave militiamen had inspired Montcalm with too much confidence in their capability. Armed solely with hunting guns without bayonets, the Canadians lost their superiority on the open field.

!-- *********** TABLE FOR GRAPHIC without COMMENT****************************** --> |

As with all tragic heroes Montcalm did not take his fatal step without being given a warning alarm. An orderly from Vaudreuil arrived and handed Montcalm a note entreating him not to precipitate an attack.

|

"The success which the English have already gained in forcing our posts should be the ultimate source of their defeat but it is in our interest not to be over hasty. They should be attacked simultaneously by our army and the fifteen hundred men from the city. In this way they will be completely surrounded and their defeat would be inevitable." Montcalm scorned this sound advice.

By nine o'clock Montcalm had formed his French and colonial forces between the citadel and the crest of rising ground beyond which waited Wolfe and his silent soldiers. Montcalm held a brief council of war with his commanders, but knowing he was resolved to attack none dared oppose him.

In His Own Words

"We cannot avoid the issue. The enemy is entrenching and already has two cannon. If we give him time to make good his position we can never attack him with the few troops we have."

By ten o'clock the rain had slackened and spears of sunlight pierced the gloom. Some saw this as an omen. Shards of sunlight shimmered on the sabres and flashed on the bayonets of the wall of red-coated regulars standing coolly confident a quarter mile distant. In their centre the multi-coloured uniforms of the Highlanders stood out in bold relief as did the nasal notes of the droning bagpipes that screamed defiance. Wolfe when told the pipes inspired the men declared, "Let them play like the devil."

Crisis led to a climax. The destiny of North America hung in the balance. Fearing further delay Montcalm prepared for a frontal assault in a frantic attempt to drive the redcoats into the river. Within hours the fate of Quebec was to be decided. The French commander was dressed in his finest green and gold-embroidered coat open to reveal a polished cuirass, [**] his cavalry breastplate and the Grand Cross of St. Louis glittering on his chest. Towering alone and aloft Montcalm was honoured by the personal devotion of his men. He spoke briefly to his troops standing shoulder to shoulder as they thought, perhaps, of the leave they'd been promised and now might never have. Instead they waited filled with panic or pleasure, excitement or dread for the order to advance and kill or be killed. Montcalm's words filled them with ardour: they were anxious to attack.

|

|

Montcalm's Cuirass |

An eighteen year old Canadien recalled the scene in his old age.

In His Own Words"Montcalm rode a black horse along the front of our lines brandishing his sword as if to excite us to do our duty. He wore a coat with wide sleeves which fell back as he raised his arm and showed the white linen of the wristband."

|

From head to foot, Montcalm in the midst of his men looked every bit the hero astride the jet-black charger, appearing as if man and horse were one. Montcalm never appeared more noble to the troops he always inspired with the martial manner they so admired.

|

|

Montcalm on his Charger |

Up went his sword. It was a general's duty to flaunt himself before his men and with sabre held high, Montcalm played the role to perfection. "Are you ready, my children?" They responded with a deep-throated bellow. The psychology of a regiment on the verge of a charge included excitement, expectation, pumping adrenalin and a keeness and care not to be seen to be dragging back. Such esprit de corps prizes power and process over contemplation and meditation. The flapping flags and fife and drums were described as unsurpassed and inspired discipline and pride. It was an exhilarating sound and sight for Frenchmen and a daunting outlook for forces awaiting the full fury of the regiment.

At this critical moment, both Montcalm and Wolfe might very well have prayed with William Shakespeare's Henry V before his attack on the French at Agincourt in 1415.

Oh God of battles! Steel my soldiers' hearts

Possess them not with fear; take from them now

The sense of reckoning, if the opposed numbers

Pluck their hearts from them. Not today, Oh Lord!

Up went the sword and so began the great Marquis's intemperate attack. The eight, six-deep battlaions stepped off together at the slow march with shouldered arms. Drums beat the pas de charge, an ominous, impetuous pounding - ta rum-dum, ta rum-dum, ta rum-dum, rum-a-dum, rum-dum! With flags high and a mighty war cry, French regulars moved off in a measured stride, flanked by Canadian militiamen, while war-whooping warriors on either side of their ranks, flitted as was their fashion into and out of the bushes. Ta rum-dum! The drums beat faster. Ta rum-dum, ta rum-dum. With their blood up and their heads down, raging men with a deep roar, swept across the plains.

The Canadian colonials had earlier been described as surpassing all the troops of the universe, owing to their skill as marksmen. On such passed occasions, they had enjoyed the benefits of a nearby woods in which to disappear, re-load, reappear and fire. Fighting a set piece battle on a flat open field was something else again. This fact that was about to be made tragically clear. Maintaining martial order may sound simple to achieve, but in the heat of battle with communications hard to hear and adrenaline flowing through the fighters' veins, it was extremely difficult to ensure. At 130 yards, the militia opened fire, then, as was their custom, they threw themselves down to re-load. Before long this distracting and disrupting procedure, began to cause the regulars' lines to lose cohesion. Ahead the red wall watched and waited with unflinching courage.

[*]Deploying foot soldiers in elongated formations to maximize their firepower left them terribly vulnerable to the volleys. A thin line of men staked everything on their ability to perform a prescribed ritual, while being subjected to fire from opposing infantry and cannonballs careering through their ranks. Confronting this fierce assault on their senses, the infantrymen could decide to fight or to flee. They had only their discipline and training to hold them to the horrors they faced. Once a line was breached or flanked, the whole could crumble.[**]Montcalm wore this piece of body armour as he rode his black horse into his final battle on the morning of September 13, 1759. Although of little value in the age of firearms, French officers wore them as a mark of rank and status. Status failed to stop bullets.

Copyright © 2013 Website Administrator