foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

LOOKING LITTLE LIKE A HERO

History reveals the truth of the human spirit.

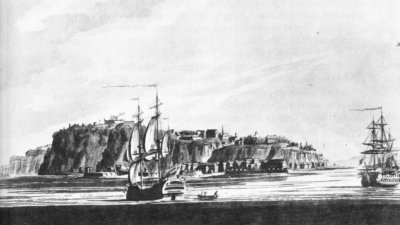

A Site Formed by Nature For Command

|

Quebec with the Plains of Abraham upper left.

|

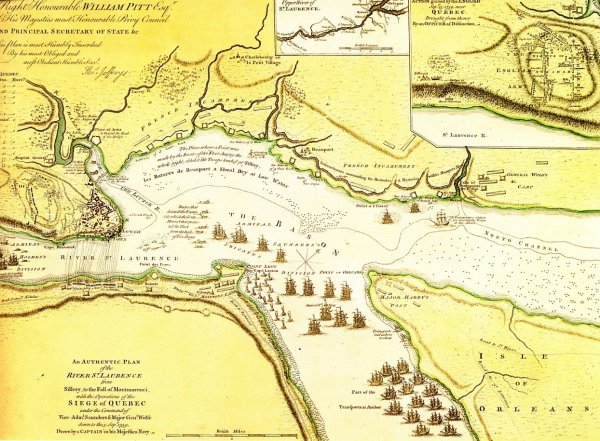

The Fleet Approaches

The British plan in North America for 1759 was to attack Canada on three fronts. One part of the army would advance up the Hudson Valley and along Lake Champlain, while the other part crossed Lake Ontario and descended the St Lawarence, the two converging on the French capital Montreal and tying down the defending forces. Meanwhile a seaborne expedition coming up the St. Lawrence would tackle the dangerous navigation and heavy fortifications of Quebec.

A deadly peril approached from the sea. The residents of Quebec were stunned by news that a great enemy fleet was fast approaching and from the town atop the heights they anxiously awaited its arrival. The gigantic armada of one hundred and forty-one ships bearing thousands "armed and trained for destruction" arrived on in May,1759. Its appearance was the most astounding sight. The awesome flotilla sailed into the mouth of the river, its vessels stretching as far as the eye could see on the horizon.

|

The oak-hulled leviathans of war filled the vast basin below Quebec and the sight their billowing sails and waving standards sent a thrill of horror through Canadians huddling behind the great walled fortress. Never before had they seen such an array of naval might and the silent scene before them spawned intense apprehension in all as they watched and waited for the storm to break.

"Everyone was stupefied at an enterprise that seemed so bold" for it was commonly believed that danger lurked in the depths of the mighty St. Lawrence River making it the colony's first line of defence. This belief stemmed in large part from a legend. It was said a ghost ship laden with red-coated soldiers appeared through the fog on dark days at the mouth of the St. Lawrence. It creaked towards the shore at Pointe aux Anglais on Egg Island, lurched on the rocks and vanished in the gloom leaving in the air the faint cries of lost men. Eight English ships were wrecked there and 900 men drowned when a British fleet was shattered in the year 17ll on its way to attack Quebec.

From that time on the myth materialized that no hostile fleet could master the treacherous river. The little settlement's chief safeguard lay in the ominous currents of the river. Fear of the water was widespread for according to Wolfe, the British sailors' dread of navigating the mighty river was "inconceivably great." It was all precarious but as the river narrowed navigation became ever more hazardous. Hidden by high tides, rough water and heavy fog the perilous reefs and treacherous currents would wreak havoc on any water-borne invasion force bold enough to brave the dangerous channel. As far as navigational hazards are concerned this stretch can have few equals in the world. It is confusing and highly menacing maze of rocks and shoals and shifting sandbars, a navigator's nightmare if ever there was one. Unless, that is, it is not accurately buoyed. The French had naturally removed every last buoy.

One of the ships, Pembroke, carried two men whose destiny was closely connected with Canada's. The ship's captain, John Simcoe, father of John Graves Simcoe, Upper Canada's first lieutenant-governor, had died en route to Quebec and was buried at sea.

The other was Captain James Cook, the ship's master, who subsequently circumnavigated the world three times. He became the greatest combination of seaman, explorer, navigator and cartographer the world ever knew then or since.

|

|

Captain James Cook |

If fell largely to Cook to re-chart and re-buoy the perilous passage. The arduous task took several weeks, a duty made more daunting because it had to be undertaken under the range of French cannons. For this reason much of the work was done at night. The French frequently used the darkness to float out from shore in canoes and cut away buoys which then had to be replaced after fresh soundings were taken.

Fear was not one-sided for notwithstanding the habitants' belief that the foggy river would deter any attacker there was always the chance some ships might make it through.

|

|

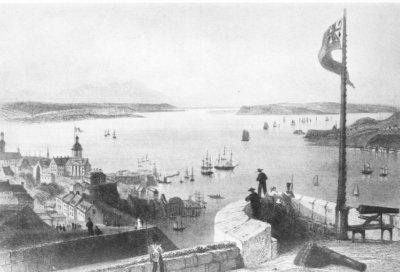

Quebec & The English Fleet |

In late June all was ready. For a whole week the great convoy dared the dangers of the passage below the island of Orleans without incident, the coloured flags in the sounding boats fluttering in the breeze. The perils of the river yielded tamely to the skills of British seamen whose neat navigation resulted largely from the competence of Cook and the care he had taken to sound out the channel and chart its tortuous waters. Canadian onlookers were dumbfounded as they watched the mighty armada sail with perfect impunity through the formidable stretch of water known as Traverse where heretofore the French had risked only a single vessel with great apprehension.

|

It was one of the greatest feats of navigation ever performed by any convoy under any circumstances. Safe and secure enough when there were plenty of aids to assist, navigation on the St. Lawrence was anything but effortless for the armada. It cruised with consummate skill through practically unknown waters and without one wreck. An English captain commented contemptuously, "Why the River Thames presented more of a challenge."

After the superb feat of pilotage up the St. Lawrence, 8500 Regular troops and six companies of Rangers landed on the Isle of Orleans, the big island in the middle of the St. Lawrence River that is more than twenty miles long and five miles wide. The Marquis de Vaudreuil was horrified. "The enemy," he wrote to the Minister of Marine in Paris, "has passed sixty ships of war where we hardly dared risk a vessel of a hundred tons.">

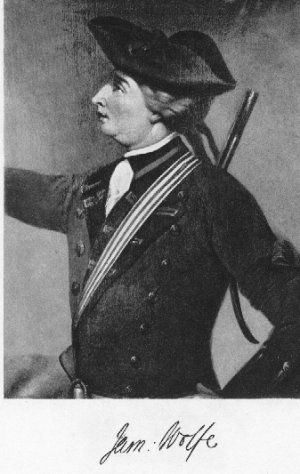

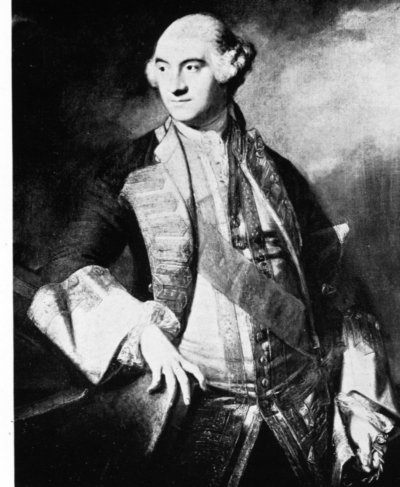

The British naval armada entered the river in June with 20 ships of the line and many smaller escorting 8000 men under James Wolfe on the deck of the Richmond. The thin, ailing, anaemic, young commander was wracked with pain and green at the gills from the stormy, sea-sickening voyage. The 32-year old fiery major general had been lauded for his Louisbourg performance as a first-class regimental commander. His fortunes there had won him a high reputation in the eyes of William Pitt and in the hearts of those who were to follow him to the Heights of Abraham. While frail of body Wolfe was fearless in action and his heroics on the field of battle won him the loyalty and love of the men he commandeded. Ambitious and covetous of reputation, Wolfe with a strike force that included some of the best units in the British army was untried as a general. He was a tactical rather than a strategic genius, a brilliant opportunist rather than a planner of campaigns.

|

|

Atop The Rock an Impregnable Quebec |

Gazing skyward at the white city and its citadel on the heights high above, Wolfe's heart skipped a beat as he surveyed the site formed by nature for command. Quebec's citadel sat secure like a medieval fortress atop the tip of a rocky peninsula that jutted out into the St. Lawrence where the river widens into a great estuary some 700 miles from the Altantic. The citadel sat on a triangular site high on the rock that plunged some three hundred feet to the river below. Wolfe was fascinated with the fortress whose seizure would be difficult if not impossible. His bulging, blue eyes blazed with fervent fire and wonder as he studied his military objective. Nature had surely bolted and barred its doors and if good fortune awaited him on this mission, it was well camouflaged. Despite having punctured the Louisbourg myth of invincibility, Wolfe was not prepared to try a direct assault on Quebec's defences. He decided against a head-on attack on the legendary citadel bristling with cannons. Even as he considered the challenge Wolfe was conscious of the possibility of landing a foce above the city. In a letter to his uncle written while at Louisbourg, Wolfe wondered at the possibility of stealing "a detachment up the river St. Lawrence and landing them three, four, five miles above the town." While he thought this was a good option, he was not at all certain they would be able to get past Quebec.

|

|

|

Montcalm gazed from the citidel at the invasion force stretching before him as far as the eye could see. His confidence was unshaken by the sight of so many warships. "Let them amuse themselves," he said derisively. Although Montcalm did not know it the man who was his match had arrived. History has linked the names of Wolfe and Montcalm in ever-lasting union. Wolfe, the younger by fifteen years, his tall spare form wasted by disease, stood in marked contrast with that of his smaller but more vigorous rival. "Two months from now they will be gone," declared Montcalm. Destiny decided otherwise.

Although physically different yet the two men were alike. Both were well versed in military science, both skilled and tactful leaders. Genius was pitted against genius. Montcalm defended while Wolfe attacked "the cautious, wily old fox."

|

|

The Citadel of Quebec |

|

Montcalm's pitiful naval force was powerless to challenge the English fleet, but the ships tugging at their anchors in the stream presented an inviting target for another tactic - fireships which had been used for centuries. After dark on June 28th, French sailors prepared the firebug fleet. They crammed seven vessels with combustibles of all types, stuffing cannon with powder and shot and plugging the muzzles with wadding. Bundles of hay and dry timber were stacked below decks. Powder kegs and barrels of tar and pitch were placed strategically about the ship. When the tide ebbed these "infernal ships" were towed into the current where the sails were unfurled. Volunteers fastened the ships' wheels to ensure a steady course while below others set fuses and kindled fires then leapt over the side into waiting boats to be rowed to safety. Flames licked along the wooden deck and then soared to the sky as these crewless, ghostly galleon incendiaries glided toward the waiting British vessels.

|

|

French Fireships |

Admiral Sir George Saunders, a bulky man with intense, bulging eyes and a great square face was a model leader of the silent service. He wrote little, said less and carried out orders with dogged reliability. This old seadog - he had joined the navy as a King's Letter boy of fourteen - had expected the fireboat gambit and prepared his crew to respond. Marine drummers sounded the alarm and called all hands to stations. Some seamen heaved on anchor cables to move the ships to safety, while others climbed over the bulwarks with long pikes preparing to fend off fiery craft. Not a single British ship was suffered from the flames that flared from the fire ships drifting harmlessly downstream or were stranded on the shore. Vaudreuil and Montcalm watched the failed fireworks from across the river. The governor was furious. Montcalm was sardonic. In his journal the next day Montcalm wrote a note about "our dear (expensive) fireships" from which he had expected little.

|

|

Admiral Sir George Saunders |

With 8000 regulars and 500 colonials, Wolfe landed at the Ile d'Orleans just downstream from Quebec on 26-27 of June and began a three month duel with Montcalm. Though an outstanding regimental officer, Wolfe soon showed himself to be a neurotic and vacillating general. The technique of brutal devastation which he learned in Scotland in 1746 stiffened the Canadians' resistance and he wasted the short season in a series of ill-managed frontal assaults. Wolfe tried several avenues of attack only to be parried by Montcalm. Wolfe had no intention of implementing "a hearts and minds policy" with the French Canadians. Believing that cannons always spoke the best language, he sought to eliminate civilian resistance by cannonading non-military targets and disrupting the movement of supplies. Despite the laws of war which forbade civilians from participating in military operations, cooperation with the military was encouraged by the French military. Wolfe was aware of some civilian involvement and he proceeded to inform inhabitants of the dreadful consequences they faced if they chose to fight alongside the French military.

In a proclamation issued on the 28th of June Wolfe gave them fair warning.

"The formidable sea and land armament, which the people of Canada, now behold in the heart of their country, is intended by the king, my master, to check the insolence of France, to revenge the insults offered to the British colonies, and totally to deprive the French of their most valuable settlement in North America. For these purposes is the formidable army under my command intended. The King of Great Britain wages no war with the industrious peasant, the sacred orders of religion, or the defenceless women and children. To these in their distressful circumstances, his Royal clemency offers protection. I expect the Canadians will take no part in the great contest between the two crowns. But if by vain obstinacy and misguided valour, Canadians presume to appear in arms, they must expect the most fatal consequences: their habitations destroyed, their sacred temples exposed to an exasperated soldiery, their harvest utterly ruined. Should you suffer yourselves to be deluded by any imaginary prospect of our want of success, should you refuse those terms and persist in opposition, then surely will the law of nations justify the waste of war and the miserable Canadians will perish by the most dismal want and famine. Britain stretches out her powerful yet merciful hand. Let the wisdom of the people of Canada show itself."

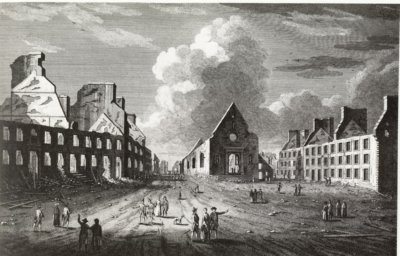

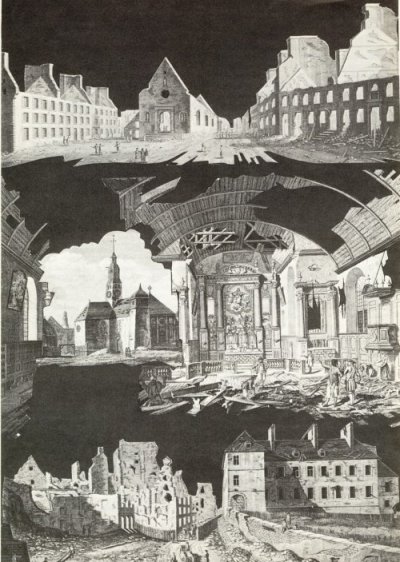

The British settled in to wear down Quebec by bombarding civilian targets in the city, disrupting supplies and spreading terror. Wolfe hoped by terrorizing the inhabitants he would convince Canadians of the futility of resisting the fury of the British assault. His orders were to wreak havoc and heartbreak and he did so by directing a merciless artillery barrage at the town. The stunning detonations of the cannonade created great suffering and destruction to the Upper Town including setting fire to the cathedral.

|

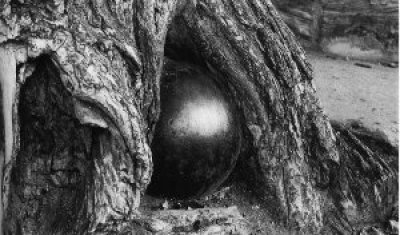

{This cannonball encased within a living tree in the city may have been shot from one of the English ships in the river below or from one of the field guns the British dragged up the cliffs and used during the Battle of the Plains of Abraham.}

The British fired some 40,000 cannonballs into Quebec during the siege, reducing much of the town to ruins. One writer [See Below *] labelled Wolfe "a borderline war criminal" whose inhumanity included "a death-hail of cannon fire heaped upon Quebec."

|

|

Quebec's Lower Town was in Ruins (R.Short, 1760, NAC) |

|

|

Bombardment of Quebec (R.Short, 1760, NAC) |

|

|

Quebec in Ruins |

Wolfe employed the tactic of laying waste the countryside, "burning houses, felling fruit trees, cutting wheat" along an eighty kilometre stretch on the south shore east of Quebec, converting "the agreeable prospect of a delightful country of windmills, water-mills, barns and farmhouses to a smoldering wasteland of rubble and ruins. Wolfe's army fired every farm in the district. Throughout the blazing countryside harassed and hungry inhabitants smoldered as they smothered in the smoke of Wolfe's terrible vengeance.

Wolfe ravaged the countryside in the hope that Montcalm would become so enraged he would rally to the rescue of his tormented countrymen. Night after night the residents of Quebec saw the glow of burning villages. Wolfe attempted justify his depradations on the population in retaliation for attacks on sentries and foraging parties by local militia. He promised to leave "famine and desolation" in his wake in order to "teach these Scoundrels to make war in a more gentlemanlike manner." No doubt these punitive raids resulted also from frustration over his failure to capture Quebec. "He vowed to do the maximum damage to city and countryside and he was a good as his word."

Any hope of motivating Montcalm to rush to the rescue of his brutally subjugated citizens was to no avail. He simply watched the wanton savaging of Canadians as they suffered death and devastation. He had no intention of exiting the citadel to end it. British soldiers were ordered to respect churches as long as the French did not use them for defensive operations. It was the civilian population not the army that suffered for the bombardment served no military purpose whatsoever. Throughout July and August, Wolfe sought without success to find an effective means of invading Quebec. Shielded by its rugged, towering cliffs the city withstood siege by land and water. British attacks east of the city suffered bloody defeats and Wolfe's persistent probings along the north shore failed to find any weakness.

Following his costly defeat after an ill-conceived attack at Montmorency, Wolfe sent a force of some 1600 men to destroy "the Buildings and Harvest of the enemy on the South Shore." The officer in charge reported, "that we marched fifty-two miles and in that distance we burnt nine hundred and ninety-eight good buildings, two Sloops, two Schooners, ten Shallops, several Batteaus and small crafts and took fifteen prisoners." The scorched-earth campaign yielded nothing but defiant derision from the destitute inhabitants.

|

Wolfe failed to find a way into the fortress guarded by guns and barricaded by nature's bulwark. Each time he thought he had found a flaw in French fortifications, he was disappointed. With the summer nearly gone and winter freeze-up about to forestall further shipments of supplies from England, the occupation of Quebec seemed as remote as ever. British troops were on short rations and more than a thousand were sick with dysentery and scurvy. An exasperated Wolfe informed Pitt that he was up against, "the strongest country in the world." To a colleague Wolfe confided, "Beyond the month of September I cannot go."

|

To make matters worse, Wolfe's recurring sickness returned towards the end of August and for several weeks he lay desperately ill in the upper chamber of the two-storey stone farmhouse at Montmorency he used as his headquarters. There are many theories about the ill health of James Wolfe. The most common is that he was suffering from consumption from which his brother Ned had died. Others believe he was suffering from rheumatic fever of which high temperature, aching joints and abdominal pains are all symptoms. It has also been suggested that the real causes were psychological and not physical. His best known recorded periods of illness coincided with periods of personal stress. In this last instance, his first real independent command was going horribly wrong and his relations with his brigadiers were at a very low ebb. He lacked the rare gift of a general: that of holding onto his brigadiers. In fact, relations with some were so bad Wolfe subsequently destroyed parts of his journal in which he had recorded "a careful account of the officers's ignoble conduct towards him in case there was a Parliamentary enquiry." He had good reason to be distressed, so distressed, in fact, that he despondently referred to "my plan of quitting the service which I am determined to do the first opportunity."

|

Gaunt with pain, his face drawn and haggard, Wolfe looked little like a hero. His driving spirit was sadly supported by a fragile frame unequal to the demands he made on it. Fatigued and frustrated by his repeated infirmities, Wolfe became despondent. His fevered mind was totally absorbed with the capture of Quebec, but the nagging sickness clouded his thinking and judgement. In the dark, muggy nights of despair and recrimination, Wolfe on his farmhouse cot must have felt he had nothing left but his spirit. He was preoccupied with his bodily woes, the lonely, self-importance of his first command and the certainty that glory or ruination was almost at hand.

Wolfe was distressed by the disagreements that marred relations between him and his three brigadiers. They resented the secretive and haughty manner with which he treated them and believed his tactics were inept. One historian called Wolfe a "Hamlet-like figure" - a good soldier but one who had enormous difficutly making up his mind. He began to mount what can only be called a confusion of orders. His brigadiers tried to follow as best they could, but the daily snarl of troop and ship movements became a joke among the ranks. Sometimes two conflicting orders arrived at the same time. Tempers flared in the confusion and vexed and angered his commanders. This was Wolfe's first independent command and he could not decide where to attack. After several weeks of indecision, he attacked at Montmorency just east of Quebec. Although the savage assaults caused a great deal of suffering for Canadians, none of Wolfe's stratagems worked.

With summer slipping away and failure staring him in the face, a frustrated and enfeebled Wolfe held a conference with his senior officers and then followed it up with a written request. "That the public service may not suffer by the general's indisposition, he directed the brigadiers to consult and consider the best method of attacking the enemy." This necessity must have been a bitter blow to Wolfe, since the brigadiers had made no secret of their crticism of his conduct of the campaign. Up until then Wolfe had made his own plans, kept his own counsel and taken full responsibility for his actions. Now he needed their help.

The brigadiers responded with a carefully developed strategy in which they recommended "directing operations above the Town" so that they could establish themselves "betwixt Montcalm and his provisions." Their plan was sound and much to their amazement the general accepted it.

|

Wolfe explained his action in a final dispatch to Pitt. "I begged the brigadiers to consider among themselves what was fittest to be done. Their sentiments were unanimous that (as the easterly winds begin to blow and ships can pass the town in the night with provisions and artillery) we should endeavour, by conveying a considerable corps up the river, to draw the French into action. I agreed to the proposal and we are now with about 3600 men waiting an opportunity to attack them when and wherever they can best be got at. The weather has been extremely unfavourable for a day or two so we have been inactive." This dispatch was written on a dreary, drizzly Sunday four days before Wolfe fell on the field of battle. Driven by the whip of frustration and dismay, Wolfe's concluding words reflected his depressed state of mind.

In His Own Words

"My constitution is entirely shattered without the consolation of having done any significant service to the state and without any prospect of it." The letter caused general consternation in London where more had been expected of Wolfe.

The passage of British ships up and down the river in front of Quebec bothered and bewildered French observers. When Wolfe broke camp at Montmorency on September 3, his departure began ten puzzling and perplexing days for Montcalm. Where had Wolfe gone? What was he doing? Where would he strike next? Montcalm never walked out nor rode out nor took a moment's recreation without the nightmare of Wolfe's whereabouts occupying his every thought.

The French intelligence network was practically non-existent and from the time Wolfe left Montmorency until he appeared atop the Plains of Abraham, Montcalm was clueless as to his location and intentions. There were few British deserters to leak military information and this coupled with Wolfe's habit of keeping his own counsel meant little was known about his plans.

|

It is a military adage that "time spent on reconnaissance is never wasted." While Montcalm's information sources were inadequate and unreliable, Wolfe had access to many 'tongues' for interrogation and he made skilled use of his excellent intelligence services. He made it a priority to be concerned about what he could not see - what was on the other side of the hill. Wolfe's own scouting parties were facilitated by Vaudreuil's loose talk and the many French deserters who were eager to reveal what they knew or claimed they knew.

By the end of September Wolfe's sickness began to subside. When word of this reached the troops, it bolstered the morale of the men whose mood mirrored their commander's health. Before long Wolfe walked among them rekindling their ardor and conveying cheer he could not share. The very sight of him "put heart into us all."

It is said there are three modes of leadership:

(1) Inspiration It is the rational appeal that attracts and inspires those to whom it is made. It can be false and if it is true it is rare.

(2) Demonstration This involves honestly sharing all one's reasons for acting and explaining where they came from and from where they will lead.

(3) Flattery This approach either fools both the leader and the followers or deceives no one.

Wolfe firmly believed that a strong spirit would carry a man through anything and he managed to motivate his men with this conviction. He led from the front and by example, saying 'come on,' not 'go on.' He never asked his regulars to do anything he would not do himself. He inspired them with his driving energy and fearlessness, and endeared them with his constant concern for their welfare. Wolfe had long since learned that "Experience shows me that pushing on smartly is the road to success."

Wolfe conveyed this simple request to his doctors.

In His Own Words

"Make me up so that I am without pain for a few days and able to do my duty. That is all that I want."

In a letter to his mother Wolfe confided, "All that I wish for myself is that I may at all times be ready and firm to meet that fate we cannot shun, and die gracefully and properly when the hour comes. My utmost desire and ambition is to look steadily upon danger."

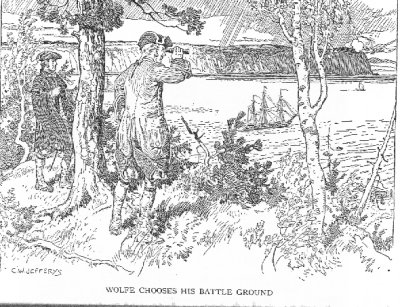

While Wolfe accepted the recommendation of his brigadiers that they attack above the town, he did not agree with their proposed location. Disguised as British regulars, Wolfe and his three brigadier stumped along the south shore looking through telescopes for a landing site opposite. Everywhere the bluffs looked formiddable. They surveyed every nook and cranny on the north shore but saw nothing of note. On September 10th the rain stopped, the sun rose radiant behind the hills and once again Wolfe scanned the shore with his telescope for a possible landing site. His perseverance paid off for less than two miles above Quebec he spotted a cove on the beach from which a narrow path wound its way through a woody precipice to the plateau. For most of the 30 miles between Quebec and Trois Rivieres the river bank was low and unguarded but Wolfe overruled his brigadiers and insisted on an extraordinarily dangerous and needless alterative: to land by night just above the city. Sea officers thought it unlikely they could find the precise landing spont on a swift current in the dark. Great skill and luck put the troop ashore at the right place. Wolfe's choice of this isolated, slippery slope to the heights was one of those quiet moments of chance that turn subsequent events on their head.

The spot, Anse au Foulon, was soon to be known as Wolfe's Cove. Inspired by a striking mixture of audacity and calculation, Wolfe believed the location which appeared to be lightly guarded with only a few white tents visible might be the site from which his men could ascend to the heights. [**] His brigadiers had suggested a more easily accessible and less risky landing further up the river. Wolfe realized the ascent of a number of soldiers at this point was perilous and would call for perfect timing and complete surprise. Despite daunting doubts he was intrigued with the idea. It was a real risk but in war there is often only one favourable moment and the great talent of the commander consists of seizing it. The site was dangerous and presented real problems, but Wolfe had made his decision. This was the place. It was a hazardous gambit to attempt: ascending a narrow trail leading up the cliffs from the river to the Plains of Abraham just southwest of the city. It was so rough that the French thought it impassable and left it lightly guarded.

|

Wolfe had frequently sought fortune in his career and lady luck had not let him down. Why should this time be any different? Fate favoured Wolfe once more. A nun later explained to her superior that a miserable deserter had provided the British with valuable intelligence. A convoy of badly needed provisions was to be sent down river to Montcalm who said, "I tremble lest they be taken and their loss undo us completely for we have only provisions enough for a few days." Ironically, this boatload of French provisions served to safeguard the British assault for if Wolfe's boats preceded these supply vessels, the redcoats might just manage to escape detection. Wolfe decided to run the risk and proceed with the landing at Anse au Foulon.

While Montcalm never mentioned his opponent by name, Wolfe made several references to his adversary in a letter to his mother. "The wary old fellow avoids an action, doubtful of the behaviour of his army, safe in the citadel high above the river in an impregnable entrenchment. I cannot getting at Montcalm without spilling a torrent of blood and perhaps to little purpose." Later as he pondered his risky plan Wolfe could not help but envy Montcalm, "the old fox"whom fortune seemed to favour.

In war one sees only one's own troubles; those of the enemy are not visible. Montcalm had more than his share of problems. He was completely deceived as to his enemy's real intentions. He was exhausted and his body ached from sitting in the saddle so long, repeatedly riding from post to post to ensure all was ready to repel any assault. He never relaxed his vigilance. He lived literally on his nerves. In a letter to another officer dated September 2nd, Montcalm wrote,

In His Own Words

The night is dark; it rains and our troops are in their tents with clothes on ready for an alarm. I am booted and my horse is saddled which is my ordinary manner at night. I wish you were here for I cannot be everywhere, though I multiply myself as well as I can. I have not been undressed since the 23rd of June."

The river side of the Plains was protected by an escarpment seemingly impossible to scale. Montcalm persisted in the belief that the cliff was inaccessible. He felt he had little to fear from the heights, for while one or two men might find a break in the cliffs and climb the narrow path to the Plains of Abraham, no army ever could.

In His Own Words

"It is not to be supposed that the enemies have wings so they can in the same night, disembark, climb the obstructed acclivity and scale the walls."

Montcalm's conversation which was always animated acquired an emotional tone as night came on. He felt a presentment of approaching danger for which he could not account. He saw peril everywhere and told Vaudreuil, "A hundred men posted there will be able to stop an army." He ordered a battalion to guard the heights, but Vaudreuil thought this madness and promptly countermanded the order and reassigned the troops. An alert sentry posted on the cliffs reported seeing British military on the opposite shore attentively surveying the heights. Once more Montcalm reacted and ordered a squad to the heights only to have the order rescinded by Vaudreuil who agreed to review the defences at Anse au Foulon the next day - September 13th.

Wolfe's brigadiers did not share his confidence and they decided to submit a request for specific directions. All three signed the memorandum to Wolfe.

In Their Own Words

"Sir, As we do not think ourselves sufficiently informed of the several facts which may fall to our share in the execution of the descent you intend tomorrow, we must beg leave to request from you as distinct orders as the nature of the thing will admit of, particularly to the place or places we are to attack. This circumstance (perhaps very decisive) we cannot learn from the public orders, neither may it be in the power of the naval officer who leads the Troops to instruct us. As we should be very sorry, no less for the public than our own sakes, to commit any mistakes, we are persuaded you will see the necessity of this application."

Wolfe treated each according to his status. Monckton, as second-in-command, was given a reasonably full explanation which included the name of the landing place. Nevertheless, he was chided by the reminder, "It is not a usual thing to point out in the public orders the direct spot of our attack, nor for any inferior officers not charged with a particular duty to ask instructions upon that point." Monckton must have thought this unjust and very nearly insulting. The second-in-command of any army might expect to be told more than was considered fit to be published in 'public orders.' As for the remark about 'inferior officers,' Wolfe was treating him as if he were a subaltern.

Townshend received even shorter shrift. "General Monckton is charged with the first landing and attack at the Foulon. If he succeeds you will be pleased to give directions that the troops afloat be set on shore with the utmost expedition as they are under your Command and when 3,600 men now in the Fleet are landed, I have no manner of doubt but that we are able to fight and beat the French Army in which I know you will give your best assistance."

Murray received no individual reply at all.

Wolfe's general response was brusque.In His Own Words "I had the honour to inform you today that it is my duty to attack the French Army. To the best of my knowledge and abilities I have fixed upon that spot where we are most likely to succeed. If I am mistaken I am sorry for it and must be answerable to His Majesty and the public for the consequences."

An unknown junior staff officer gave the following account of what occurred at this time.

In His Own Words"The 11th orders were given to prepare for landing and attacking the enemy. Wolfe's orders were extremely detailed as to the order of regiments and the distribution of boats but gave no landing place. Mr. Wolfe rec'd a letter signed by each of the Brigadiers setting forth that they did no know where they were to land and attack the enemy. On the 12th Mr. Monckton came aboard the Sutherlandin the morning. After he had gone, Mr. Wolfe said to his own family that the Brigadiers had brought him to the river and now flinch'd. He did not hesitate to say that two of them were cowards and one a Villain."

Wolfe on the 12th of September 1759 on board the flagship Sutherland issued his last general orders - a call to battle. Written in his elegant handwriting the orders are still preserved on the fading, brittle pages of the aging orders book at the National Army Museum in Chelsea, England.

|

In His Own Words

"The Enemy's Forces are now divided, there is great scarcity of Provisions in their Camp, & universal discontent among the Canadians.¨ A vigorous blow struck by the Army at this juncture may determine the fate of Canada. Troops will land where the Enemy seems least to expect it. The Officers & Men will remember what their Country expects from them, and what a determined body of Soldiers are capable of doing against five weak Battalions mingled with a disorderly Peasantry. Soldiers must be attentive and obedient to their Officers & the Officers resolute in the execution of their duty."

The men cheered as this Nelsonian flourish in the last two sentences was read out to them. Wolfe's continuing concern for the men's welfare was evident for the orders ended with the comforting words, "The ships with the Blankets, Tents and Necessaries will soon be up."

The watchword was Coventry which was probably suggested by the saying 'Sent to Coventry' which meant condemned to silence, an apt phrase for the work to come.

Having completed all his orders Wolfe confided to an old friend, John Jervis, that he expected to die in the forthcoming battle. Taking from his waistcoat a medallion in which he had a portrait of his financee, Katherine Lowther, he gave it to Jervis to give to her should his fears be fulfilled.

|

The spirit of the army matched that of their chief whose restless energy became contagious. Wolfe captured and kept the confidence and affectionate loyalty of his soldiers. They loved and admired him and also trusted their officers. In the words of a sergeant named John Johnson, "We have seen them tried and they are sterling." The redcoats had no fears about following their leaders.

Wolfe dressed for battle. His servant, Francois, had laid out on his bunk the new scarlet coat with its blue lining, white facings and gold trim, a snowy fresh shirt with lace jabot and cuffs, warm waistcoat and white breeches and stockings. His boots were brilliantly polished. The belt for the small hanger sword he seldom wore was pipe-clayed to perfection. Wolfe dressed and inspected his face in a small mirror noting the blotches and thin lines of pain around the two bright eyes. Spirit! If a man had spirit he could conquer all. He held out his left arm so Francois could tie on the black band he wore in memory of his father. He donned the heavy gray greatcoat, grasped his stick and strode out on deck. Fortune or failure awaited.

The regiments were formed into three brigades; each man carried his musket, food and rum for two days. After eating their supper the troops climbed quietly into flatboats at nine o'clock. The ships were scattered over a long stretch of the river and to assemble the boats in darkness was a delicate operation. Twenty-four Scots light infantry volunteers were selected to lead the desperate mission about which even the senior officers knew very little. The soldiers were told simply that their assignment "involved climbing." They formed the regiment's 'Forlorn Hope,'[****] the name given a select group of courageous men sent ahead of the main body of men to accomplish a difficult and dangerous mission.

There was no shortage of volunteers to undertake the dangerous ascent. A terse note by one of them records, "fine weather, the night calm, and silence over all." This storming party was led by William DeLaune, a captain whom Wolfe held in high esteem. "If any of us survive," said DeLaune, "we may be recommended to the general for bravery." In his will Wolfe left Delaune and five other officers "each a hundred guineas to buy swords and rings in remembrance of their Friend."

For the next five hours they sat silently in full uniform on hard wooden boards, back to back, four men across with packs at their feet. Sailors trained to row the boats squeezed fore and aft in each vessel. Absolute silence was essential and the men were ordered to say nothing. Near two o'clock on the morning of the 13th, a fresh east wind arose and the tide, the army's unwitting ally, began to ebb. Major-General James Wolfe clambered down a ladder on the starboard side of the 50-gun flagship, HMS Sutherland, and settled his long, painfully-thin frame into the stern of the crowded, flat-bottomed boat. At the appointed signal - two lanterns raised to the maintop shrouds of the Sutherland - the boats cast off and with the precision of a parade-ground movement they formed into line, eased silently into the current and disappeared into the blackness of the chilly night on their trip to the trail. It was a journey into history. The next few hours would decide who would rule North America.

|

|

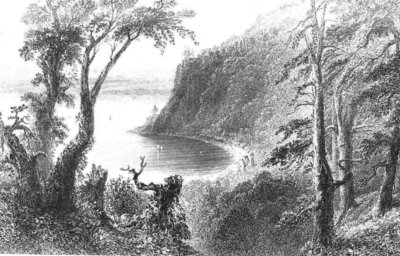

View of Wolfe's Cove - The path up which Wolfe's army climbed lies in the gully at the foot of the picture. The buildings on the right were not standing in 1759. |

|

|

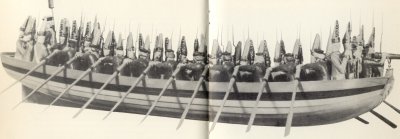

Model of Invasion Barge used by Wolfe to carry assault force to the cliffs below Quebec [26] |

|

|

Wolfe's way to History |

This is a model of the 30 vessels used to transport Wolfe's warriors with their rifles upright to the Plains of Abraham. The boat crew rowed as a coxswain, accompanied by a piper and a drummer, steered from the stern. These boats were widely used by the British navy when amphibious warfare was involved to get troops across lakes, rivers, or onto a coastline, as ships moored off the coastline bombarded battlements ashore. The boats, broken down in kit form and nestled inside each other were transported by ships to shore where they were reconstructed for use.

|

There was no moon to disclose their presence. Wolfe, sick, nervous and afraid - not of death, but of defeat - had but eight hours left to live. He reflected on his perilous plan. Failure to scale the heights would result in appalling disaster and defeat. The loss of half a continent rested on the success of this precarious assault. Audacity, cleverness and originality were the needs of the hour.

|

|

Quebec Assault Drawn by an Aide of General James Wolfe |

|

One military historian said of warfare, "No human activity is so continuously or universally bound up with chance." It was a difficult and dangerous amphibious operation. Some 1800 troops had to be conducted in boats almost fifty kilometres downstream in a strong current in complete secrecy, then landed on a thin strip of beach. Early morning mists intensified the blackness enshrouding the convoy of thirty batteaux bearing the shadowy figures sitting silently in the flat-bottomed boats. There was no straining at the muffled oars for a three-knot current lent strength to the oarsmen as they moved effortlessly and soundlessly down the St. Lawrence River. .Hugging the shore they coasted cautiously along the narrow stretch of water for two hours before the tide began to ease them towards the shore. Suddenly a wall of rock and trees loomed up before them. Out of the night came a challenge from a French sentry: "Qui vive?" As quickly as the question came, the reply was given, "France, vive le roi." History held its breath.

The sentry knew French provision ships were due in the area and fearful too much talking would alert the British to their presence, he allowed the boats to proceed without seeking the password. [*****] A French officer said later he heard boats being rowed back and forth and reported this to a superior who did not pass on the information.

The choice of Anse au Foulon as the landing place presented an extreme challenge but with risk and peril on every side vision and imagination were needed. The troops had to land on a narrow beach in a current of four knots on the ebbing tide, an extremely difficult task. Before them rose a 60 metre high bluff of rocks, small trees and bushes, its side scared by a trail that zigzagged up to the heights. Nothing less than the destruction of Montcalm's army could justify the rashness of this enterprise.

|

|

The Taking of Quebec (Imagine it's Dark) [25] |

One of Wolfe's junior staff officers provided this account of the action.

In His Own Words

"The boats fell down about half an hour after three, and arrived at the Foulon half after four without striking with oars merely by the force of the Tide which was 9 mile. How with the Light Infantry gain'd the Heights with little loss, the enemy had a hundred men to Guard the Foulon which were soon dispersed. Mr. Wolfe was Highly Pleased with the measures Col. Howe had taken to gain the Heights.

Muffled orders were followed by splashes and scraping sounds as the boats grounded on the shingle of Foulon. Wolfe's pessimistic pronouncement upon landing did not auger well for the enterprise.

In His Own Words

"I don't think we can by any possible means get up here; It might indeed be a forlorn hope, but we must use our best endeavour."

Daring was the only path to victory and the last few hours had been in themselves a lifetime. So much had happened and everything had gone faultlessly. It was possible to conceive a plan, run through it over and over again studying and revising the smallest detail but even then something could go wrong - a small thing, a trifling mistake - which could convert the operation into chaos. Not this time. It was almost too good to be true.

The curtain of night that had helped by hiding the boats now increased the hazard of climbing a wooded, unexplored cliff face made slippery by the previous days of rain. Weighted down with heavy packs, the men of the Forlorn Hope jumped ashore, scrambled up the greasy, perilous pitch scattering stones and mud as they clutched wildly at brambles and brushes to assist their ascent to the plateau. On reaching the top they moved cautiously towards the faint, flickering lights coming from a small cluster of tents. Awakened by the noise, French guards within roused themselves and staggered into the darkness only to find themselves face to face with fixed bayonets. Scattered fire from the pickets rang out and a brief skirmish followed. Taken completely by surprise the few French defenders offered little resistance and were quickly routed. The way was open for the army to follow.

A junior staff officer of Wolfe's left this record of the action.In His Own Words

"The General stopped further debarkation of the troops until the first were well established above, saying if the Post was to be carry'd there were enough ashore for that Purpose, if they were repuls'd a greater number would breed confusion."

Vice Admiral Charles Saunders provided this description of the moment. "Considering the darkness of the night and the rapidity of the current, this was a very critical operation and very properly and successfully conducted. When General Wolfe and the troops with him had landed, the difficutly of gaining the top of the hill is scarce credible. It was very steep in its ascent and high and had no pathwhere two could go a-breast. But they were obliged to pull themselves up by the stumps and boughs of tres that covered the declivity."

|

|

Wolfe Leads the Night Attack On Quebec [27] |

|

|

|

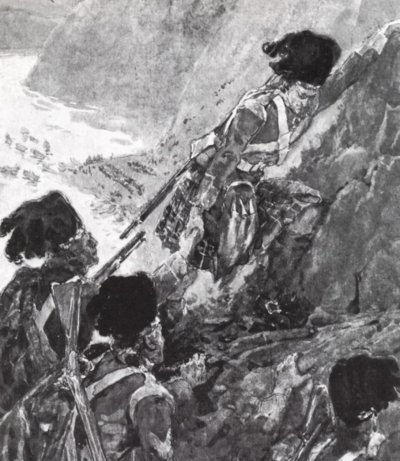

Up, Up, Up the 175-foot Cliffs Go the Highlanders |

|

|

Heave Ho The Highlanders |

When Wolfe heard the gunfire his heart sank for he feared his plan had failed. A triumphant cry from the Highlanders told him all was well. The remaining troops lept from the boats and with muskets strung with the packs at their backs they puffed up the path in a steady stream. Stimulated by the excitement of the assault, Wolfe climbed out of the boat and began his ascent. Weakened by blood-letting and the feverish illness that still dogged him, he dragged his diseased body up the slope. Around him the cliff face was crawling with confused, stumbling, straining soldiers, some of whom twisted their ankles and dropped their weapons. Wolfe's determination was close to frenzy. The going was steep and rough but by grabbing at bushes, clawing at loose earth and occasionally being supported by his soldiers, he reached the top.[***] This small success seemed to revive him. The prospect of battle made him forget himself and his physical distress.

|

In the grey morning light of the dreary, rainy day, the scarlet file wound its way up the incline to the tableland at the top. By dawn the last sweating soldiers had hauled himself up to the summit where the redcoats quickly established a bridgehead. Although the tide had carried them a little past their intended landing place, the combined army and naval operation was "a professional triumph." The plains lay before Wolfe. Buoyed by the priceless treasure of surprise, Wolfe prepared for the supreme issue at stake and formed up his army undisturbed for as yet the plains before him were open and undefended. The French were nowhere to be seen. Through a combination of skill and luck Wolfe had accomplished the feat and by the next morning he had 4800 troops on the plains.

|

|

Wolfe Climbing the Heights In Daylight and Dignity by R.Caton Woodville |

[*] McLynn, Frank, 1759: The Year Britain Became Master of The World 2004

[**] Some writers believe this version of Wolfe suddenly spying with his little eye the site that made his success possible a little too simplistic. They propose another explanation: Treachery! If Quebec were destroyed by the British, incriminating records that would expose the skullduggery of the French officials would be lost or ruined. Montcalm himself suggested as much when he said: "Everybody appears to be in a hurry to make his fortune before the colony is lost, an event many perhaps desire as an impenetrable veil over their conduct." Bigot and his thieving accomplices had every reason to fear for their future should inquiries in France reveal their criminal acts. French defeat would mean the destruction of all documentation, thus conveniently eliminating all evidence of their evil doing. Perhaps, therefore, one of culprits decided to facilitate the French downfall by informing Wolfe of the Anse du Foulon. It was Vaudreuil himself who quickly countermanded Montcalm's order to fortify the heights. Perhaps as one nun suggested Wolfe was informed by a French prisoner or deserter. No one knows for certain. [***] Wolfe's landing place has long since disappeared under a modern ocean terminal. The actual cliff he climbed is still there. Countless numbers of history's 'heroes' delight in scrambling up in the wake of Wolfe, dreaming, no doubt, that they are the dauntless victor. [****] 'Forlorn Hope' has nothing to do with 'forlorn' or 'hope.' It is a corruption of the Dutch verloren hoop meaning 'lost company' or 'lost troop'. The emphasis is on 'lost' because of the danger involved in their risky assignment, they may never be seen again. [*****] British passwords or what were then called paroles or countersigns were changed daily and applied to the whole force. They were often the names of cities, e.g. London, in order to make it easier for the men to remember them. Officers had to ensure that all troops were informed each time the countersign was changed. Any general who wished to check on whether his orders were being passed on to the soldiers could simply do so by asking a private soldier what the parole was.