foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

MARQUIS - MAN ON THE ROCK

History is the chronicle of famous men.

|

|

Montcalm |

The adage "war is the grave of the Montcalms" is as old as France itself. Members of this illustrious French family had fought for king and country since the time of the Crusades. Louis Joseph, Canada's Marquis de Montcalm, was no exception. He was an aristocrat of distinguished lineage and a soldier of great experience. His ancestors like those of Wolfe had won renown on the field of conflict. The battle-tried Montcalm is considered by some historians as one of the greatest field generals of the Seven Years' War.

Montcalm was a leap year baby born at the chateau of Candiac near Nimes, France on the 29th of February, 1712. Initially, he had many difficulties in school. He found it hard to concentrate and frequently rebelled against the harsh system of discipline. Montcalm's despairing private tutor considered the young Montcalm "too opinionated." The boy's inability to learn grammar and his extremely poor penmanship caused his frustrated master to exclaim in anguish, "He has great need of docility, industry and willingness to take advice. What will become of him?" Things were to improve. Thanks to a good memory, bright intelligence and hard work Montcalm began to excel in his schoolwork and he made rapid progress in the study of Latin, Greek and history. He promised his father that he would be "a man of honour, brave and a good Christian." He never disappointed his father.

|

In 1727, the year of Wolfe's birth, Montcalm joined his father's regiment as an ensign and six years later underwent his baptism of fire. His bravery on this occasion did not belie the bravery of his ancestors. The death of his father brought the young officer back to the paternal chateau, dear Candiac, now his own property. He married Angelique-Louise Talon du Boulay who by a strange coincidence had relations in Canada. Her grand uncle was the famous Intendant Jean Talon, who founded the royal administration in Quebec. They had ten children of whom six survived: two boys and four girls. Montcalm was a family man and loved the companionship of his wife and children. He was distraught to learn of the death of one of his daughters while he was in Canada. He never did find out which of the girls it was.

|

|

Candiac, the home of the Montcalms in Provence |

When conflict commenced between France and Britain in 1755 a French commander was required in New France. Because war threatened in Europe and offered opportunities for rapid promotion and instant fame, senior military men were reluctant to leave the country. As a result lower echelon officers were selected for military leadership roles in the distant colonies, one of whom was Montcalm.

On March 14, 1756 Marquis de Montcalm descended the grand staircase of the palace of Versailles where he had just received his final orders from King Louis XV. He was assigned to service in Canada with the rank of major-general but with command over troupes de terre (land forces)only. His commission clearly stated that he was to be subordinate to the Marquis de Vaudreuil who was given overall command of all military forces.

The voyage was a rough one. In a letter to his wife Montcalm wrote, "I have been fortunate in not being ill nor at all incommoded by the heavy gale we had. I must tell you of our pleasures which were fishing for cod and eating it. The taste is exquisite. My health is as good as it has been for a long time.>" Montcalm found Quebec to be different in many ways. It was a young society compared to the old world he had left. Nature was wild and ruggedly beautiful compared to the soft, sunny, smiling landscapes of France. The limited area within the walls of Quebec swarmed with soldiers, militiamen and Natives.

The three palaces of the governor, the indendant and the bishop were visible reminders of the triple power radiating throughout Quebec.Montcalm sent a messenger to M. de Vaudreuil to notify him of his arrival. Their first meeting did not foreshadow the hostility which arose between the two men with such disatrous conseqences for the colony. Vaudreuil, a tall, impressive man, was as proud of his person as of his origin - Quebec. During their conversation he eyed the small sprightly individual whose piercing eyes and short vehement words indicated a domineering force and strong will power. Montcalm was as yet unaware of the animosity inspired by his words, but instead flattered himself that his military superiority would ensure his ready acceptance with good grace by the governor.

In Montcalm Canada gained one of France's ablest and most ambitious soldiers. His gallantry, chivalry and impressive appearance won him devoted admirers. Historian Francis Parkman described Montcalm as " a man small in stature with a lively countenance, a keen eye and in moments of animation of rapid, vehement utterance and nervous gesticulation." He was also vain, opinionated and stubborn and quick to fly into a rage at the slightest provocation, but equally quick to bring his emotions under control.

Montcalm was skilled and courageous in battle and his many triumphs in the field accustomed him to celebrating successes. Early in his Canadian career Montcalm using bold enterprise and skilful tactics and following a four-day siege the white flag was raised at the British fort at Oswego. Hated Oswego was laid in ashes. This victory gave France undisputed command of Lake Ontario and her communications with the west were safe. The stunning defeat of Anglo-American forces opened up the frontier of New York to invasion and thereafter fear of French raids in force haunted the English colonies.

In a letter to his wife, Montcalm was particularly critical of his red allies. "You would not believe it but the men always carry to war, along with their tomahawk and gun, a mirror to daub their faces with various colours and arrange feathers on thier heads and rings in their ears and noses. They think it great beauty to cut the rim of the ear and stretch it till it reaches the shoulder. One needs the patience of an angel to get on with them." What the Aboriginal warriors thought of the French was not recorded.

Despite being volatile and often unpredictable, the native braves were very valuable allies, not least for the terror they inspired in those who opposed them. What could be done against an invisible foe who struck and then vanished as quick as lightning. According to one French leader, "they must be sent home satisfied at any cost." No one dared offend their wavering tribes because without warning they might very well decide to join the English.

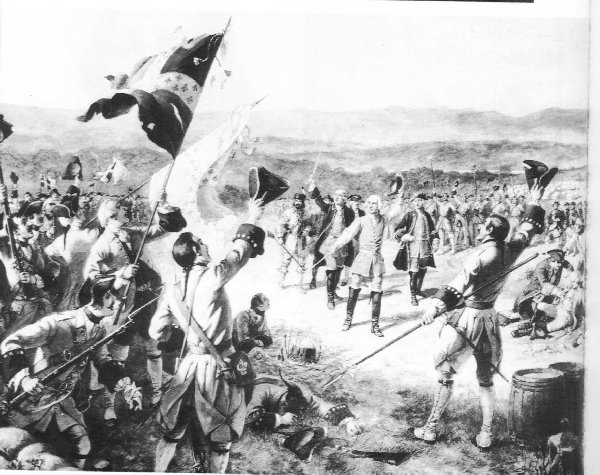

Montcalm knew this better than most. In 1757 on the first of August at two in the afternoon, Montcalm with a force of some seven thousand men and more than sixteen hundred Indian allies set out for Fort William Henry at the head of Lake George. Prior to the assault on the fort, Montcalm addressed chiefs and the host of warriors before him all decked with ceremonial paint, scalp-locks, eagle plumes and horns of the buffalo. Edged about this fearsome force were the white uniforms of officers of France.

|

|

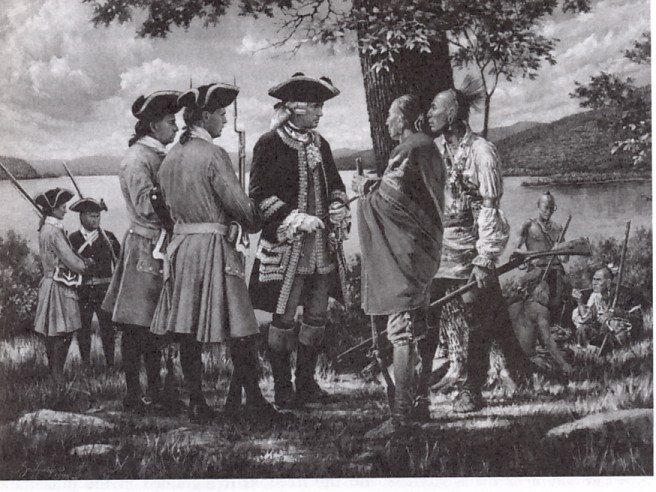

Montcalm Meets Indian Chiefs |

"Children, I am delighted to see you all joined in this good work. So long as you remain one, the English cannot resist you. The great King has sent me to protect and defend you; but above all he has charged me to make you happy and unconquerable by establishing among you the union which ought to prevail among brothers, children of one father, the great Onontio." He then held out a great wampum belt of six thousand beads. "Take this sacred pledge of his word. The union of the beads of which it is made is the sign of your united strength. By it I bind you all together so that none of you can separate from the rest till the English are defeated and their fort destroyed."

|

|

Montcalm Leading his troops |

French cannon bombarded Fort William Henry and before long much of its rampart was battered down. British cannons and mortars had all been burst or disabled by French fire. The fort's walls had already been breached and an all-out assault was imminent. Finally a white flag was raised, a drum beat and an officer on horseback followed by a few redcoats was led to the tent of Montcalm. It was agreed the English troops would march out with all the honours of war. Before signing the capitulation, Montcalm called the Indian chiefs to council and asked them to agree to the terms and promise to prevent their young warriors from any kind of disorder. They agreed fully. Unfortunately, they were unable to fulfill their agreement and in the melee that followed, many British prisoners were killed after surrendering.

In July 1758 the British commander, Major-General James Abercrombie, an elderly man unwell in mind and body, was given command of an expedition of 6000 British regulars and 9000 colonial troops, the largest single army ever assembled in America. Their objective was the capture of Fort Carillon [See Below *] on Lake Champlain. Montcalm commanded the French garrison about to be assaulted by the overwhelmingly superior British force. The Battle of Carillon is believed by some historians to be a classic example of tactical military incompetence. Abercrombie, confident of a quick victory, ignored several viable military options such as trying to flank the breastworks, waiting for artillery reinforcements or bypassing the fort entirely. Instead on the urging of his engineers he decided in favor of an unsuccessful frontal as

|

Prior to the commencement of the battle, Montcalm doffed his military jacket in the suffocating heat, remarking to his men as he did so, "We will have a warm time of it today, my friends." They did, indeed, for the British were out-generalled at every turn and decisively defeated by Montcalm's strategy. His 3600 white-uniformed regulars coolly cut down the assaulting redcoats, who were foolishly fed into the French mincing machine by their incompetent commander.

|

|

Montcalm Celebrating Success with His Soldiers[23] |

Montcalm's plump face, small stature, delicate manner and bubbling speech deceived the homespun Canadian Governor Vaudreuil, but an Aboriginal chief saw his true capacity. "We wanted to see this famous man who tramples the English underfoot. We thought we would find him so tall his head would be lost in the clouds. But you are a little man my father. It is when we look into your eyes that we see the greatness of the pine tree and the fire of the eagle."

Montcalm's striking success was celebrated in Paris with prayers of thanksgiving, fireworks, free wine and dancing in the streets. His name and fame spread throughout the army. Young officers competed to join his forces in the field and when volunteers from the ranks were called to serve under him, every single soldier stepped forward.

|

Despite Montcalm's successes in the field little money and fewer troops were forthcoming from France. Besieged by superior British forces it was not long his position became untenable. While French forces, munitions and rations were increasingly in short supply, there was no deficiency in the flow from Britain. Montcalm's pleas to Paris for reinforcements to keep pace with those pouring into Canada from Britain were in vain. Instead he received decorations and dispatch bags full of advice but fresh fighting forces were limited to a token 300-600 troops.

|

Montcalm quickly realized that he was dealing with an enemy superior in men and money and mighty on land and on the water. Strong British offensives compelled the French to fall back from their outlying locations and gradually concentrate their troops in the heart of the colony - the fortified town of Quebec. In the quiet moments at his lodging, he soothed himself by writing of his contempt for the Governor and the ridiculousness of the situation. Vehicles are lacking for work on the fortifications, but not for carrying materials for making a casement for Madame Pean (Bigot's lady friend). No matter how tragic the end of all this may be, one cannot help laughing."

|

Through no fault of his own, Montcalm was ill-prepared to face the forces of a tough adversary about to assault the Rock. Time was on Montcalm's side, however, and he prudently decided sit tight and undertake no initiatives, wisely deciding to await Wolfe's attack behind the walls of his fortress. Here supported by officers and men inspired by his leadership, Montcalm prepared to make his stand. The bastion of Quebec was believed to be impregnable. History's boot was poised and about to stamp down.

[*] The following year the fort was captured by the British and renamed Fort Ticonderoga.Copyright © 2013 Website Administrator