foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

IN COMMAND UP THE RIVER

History is determined by the choices people make.

Wolfe was intrigued by the new world and set down his thoughts on the future of America in a letter to his mother. "This will some time hence be a vast empire, the seat of power and learning. They have all the materials ready. Nature has refused them nothing and there will grow a people out of our little spot (England) that will fill this vast space and divide this great portion of the Globe with the Spaniards who are possessed of the other half." Wolfe himself was to do as much as anyone towards the fulfillment of his prophecy.

|

|

Admiral Lord Richard Howe |

the cornerstone would probably have been laid of this high Fabrick." A year later Wolfe was the lay the great stone himself.

Following their capture of Lousisboug, Wolfe urged an attack on Quebec but Boscawem and Amherst decided that should wait until the following year. Frustrated by the delay and worn and weakened by the strenuous campaign, Wolfe returned to England on the Namur and after a fast but miserable passage of a month, Wolfe, seasick as usual, arrived at Portsmouth on November 1, 1758. He was summoned to an interview with Lord Ligonier, Britain's commander-in-chief and during their discussions of the Quebec campaign to come, Wolfe indicated that although he wanted to be involved, he asked to be excused from taking the chief direction of such a weighty exercise. Nevertheless, it was his fervent wish

In His Own Words

"to go up the River" (St. Lawrence)

|

|

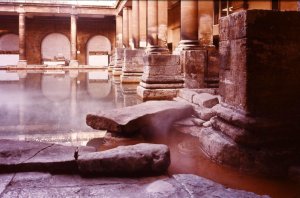

Bath In The 18th Century |

|

|

Bath |

|

|

Bath |

Following Wolfe's return from Louisbourg he spent some time at the resort at Bath in an attempt to restore his unstable health. At Bath he lodged at Queens Square "to be more at leisure, more in the air and nearer the country." Here and elsewhere he received an enthusiastic welcome for his originality and his daring and intrepid risk-running made him very popular with the public. He found his praises in everyone's mouth.

|

|

Wolfe in 1758 at Bath. In his left hand is a plan of Louisbourg. |

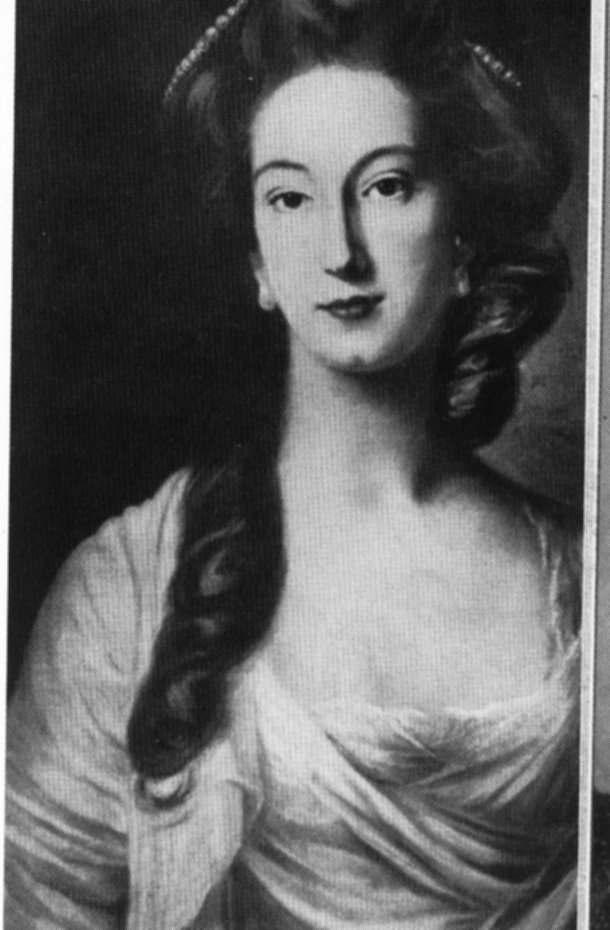

Wolfe's stated reason for going to Bath was his poor health, but it must have improved somewhat by finding there Miss Katherine Lowther, a young woman with large, dreamy eyes and long lustrous hair. Wolfe had met her there previously.

|

|

Katherine Lowther |

Her father was a former governor of Barbados and her brother, Sir James Lowther, was very wealthy. Katherine was thought to be 'a good catch'. Wolfe had fallen deeply in love with her and while it was certainly not Wolfe's wealth that attracted her, Katherine fell in love with him. She was beautiful and he was a hero about whom the family could hardly object when he had promise of becoming a world-renowned general. Her family approved of her sudden romance with Britain's latest celebrity. The young couple became engaged and Wolfe divided the remainder of his time in England between courting Katherine and preparing for his departure for Quebec.

|

|

Katherine Lowther |

Of Wolfe's leave-taking from Katherine Lowther nothing is known. Some time in January he asked her to marry him and was accepted. Before he left England she gave him her portrait in miniature small enough to fit into a locket her lover carried with him. She also gave him a lock of her hair and a copy of Gray's Elegy in a Country Churchyard. Wolfe sat for a large portrait wearing a wig, no hat, a white shirt with a black neck tie and a crimson coat. Wolfe's choice did not meet with parental approval and little was said of his love for Katherine.

|

|

James Wolf |

Wolfe's mother, Henrietta, was a rather domineering and possessive parent. She disapproved strongly of Wolfe's first love, a young lady named Elizabeth Lawson, believing her son could do better financially by marrying a wealthier woman. Wolfe had an explosive temper and this incident resulted in a coolness developing for a short time between him and his mother. Mrs. Wolfe also opposed her son's involvement with Miss Lowther. What she had against a young woman who belonged to one of the most influential families in the north of England was never discovered. The hostility was strong and bitter and was made moreso by the fact that her son disregarded her objections.

|

|

Elizabeth Lawson |

In the early stages of the British-French conflict called the Seven Year's War, things had gone badly for Britain. In the midst of the nation's crisis a man named Pitt answered the call of his country. William Pitt the Elder was obsessed with delusions of grandeur and even called mad by some, but there raged within him a clarity of purpose and a driven sense of duty. Unmindful of any modesty, he forthrightly declared, "I am sure I can save this country and that nobody else can." He who was nothing if not decisive and set about putting British money where his mouth was.

Frequently in pain from gout, Pitt often arrived at the House of Commons with his legs swathed in flannel and his arm dangling in a sling. Despite his physical failings, his eyes flashed with fire, as he held the House entranced with a marvelous voice, so rich and clear, that even when it sank to a whisper, it could be heard in the remotest benches. When he thundered forth with its fullest strength, the sound shook the chamber and could be heard through the lobbies and down the staircases of Westminster Hall.

|

|

William Pitt the Elder |

Physically Pitt was short, slight and habitually bore a grim, determined expression. He had "a little head, the eye of a hawk and a long acquisitive nose." He was very dignified, utterly devoid of a sense of humour and so imperious a person, he never permitted his secretaries to sit in his presence. He was ostentacious and rudely contemptuous of ordinary politicians, who found him a difficult person to like. Secretive, sensitive, bossy, domineering and distrustful, he was considered by those with whom he worked, "a bad colleague." He was a good father, who delighted in the merriment of his children and loved to relax with them hunting butterflies. He called the comments of their nurse about the children "little-great things" that were far more interesting than the "great-little things of the restless world."

Success in every great conflict can often be attributed to one dominating personality. During this period in Great Britain's history North America, that person was Pitt. His vision and imagination were contagious and his eloquence compelling. His fiery speeches made him one of the great orators of all time. Renewed confidence swept through the country and the heart of the nation beat with a new vitality when Pitt assumed direction of the war with France. In this unrivalled war leader, there actually was a strain of madness and later life Pitt became manic depressive. Fortunately for Britain in her hour of need, Pitt was certainly sane when called upon by his country, to confront France and eliminate her as a great colonial power.

It was Pitt who picked the men that mattered, and he saw in Wolfe a tactician and daring combat commander who could move fast and strike hard. When Wolfe returned to England after the Louisbourg campaign, Pitt was disappointed, for he wanted him to remain in America over the winter, so there would be no delay in launching the Quebec campaign. When Wolfe learned of Pitt's dismay, he dashed off a note to assure him that he had been unaware of Pitt's plans and confirmed that he had "no objection to serving in America and particularly in the river St. Lawrence."

Wolfe's stay at Bath was interrupted on January 5, 1759, when he was summoned on a misty evening to Pitt's country home, Hayes just outside London. Wolfe was astonished to be told that he had been selected to lead the assault on Quebec. Wolfe's reserved response was that while he had not sought the top job, the prime minister could

In Pitt's Own Words

"dispose of my slight carcass as he pleases. I am to willing to undertake anything within the reach and compass of my skill and cunning."

It was said of Pitt that no one departed from his presence without leaving a braver man. Wolfe, who was no exception, declared it was, "not his part to choose but to obey."

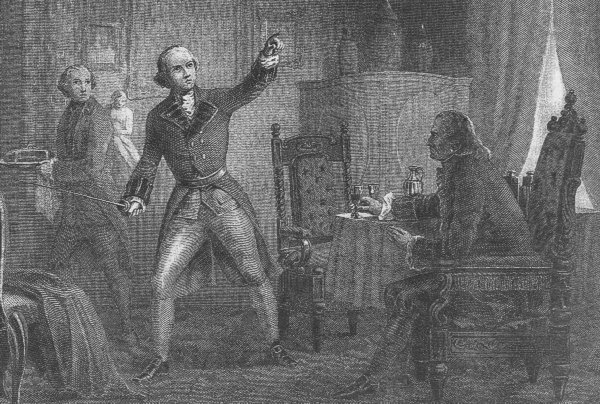

Before departing for Halifax, Wolfe dined one foggy February evening with Pitt and his brother-in-law, Lord Temple. An bizarre incident occurred at the dinner, which has given great trouble to Wolfe's biographers. According to Temple, late in the evening, Wolfe "broke forth into a strain of gasconade and bravado. He drew his sword, rapped the table with it and flourished it around the room, all the while talking of the mighty things which that sword was to achieve." His two companions looked on in amazement.

|

|

En Garde |

Then without a word, Wolfe turned and left the room. Pitt, lifting up his eyes and arms exclaimed in astonishment, "Good Lord, to think I have entrusted the fate of the country and the administration to such hands." Some historians doubt this ever happened, while others suggest this uncharacteristic outburst resulted from too much wine, for Wolfe, who was a teetotaller, very rarely touched a drop. [*]

It was not long after this episode, that the Duke of Newcastle was dumbfounded when he learned Wolfe's promotion and that the prominent appointment was based on competence alone. In a fit of pique, Newcastle told George II that not only was Wolfe too young to command such an important expedition, he was also deemed demented. According to legend, the old king is supposed to have growled in reply, "Mad is he, then I hope he will bite some of my other generals." When news of the French defeat on the Plains of Abraham reached England, the king was undoubtedly delighted that the victory had vindicated his choice of commander.

|

|

George II |

Even though military service in America was not eagerly sought by senior British officers, Pitt assumed a real risk by appointing a mere colonel to command what was going to be a major mission. Despite Wolfe's meagre military experience as a senior officer, who had neither ever planned nor carried out an independent campaign, his recently won reputation at Louisbourg made him a prominent and popular choice. Wolfe himself had his doubts. In a letter to his father's younger brother, Uncle Walter, informing him of Pitt's decision, Wolfe wrote, "I am to act a greater part in this business than I wished or desired. The backwardness of some of the older officers has in some measures forced the government to come down so low. I shall do my best and leave the rest to fortune as perforce we must, when there are not the most commanding abilities."

James Wolfe's "accustomed place was at the cannon's mouth" and this time he placed there by Pitt, who personally recommended him to King George II for "the command in the River."

To select the right man to command an expeditionary force, the government often chose a comparatively junior officer and endowed him with a temporary rank. Wolfe's commission designated him commander-in-chief of the land forces for the offensive against Quebec, for which the king assigned him the rank of major-general. In order to soften this perceived slight to the more senior officers, the king informed Wolfe he would hold this rank, "in America only." Later in secret instructions to Wolfe, the king directed that at the conclusion of the Quebec campaign, Wolfe was to place himself, "as brigadier-general in North America," under the command of General Amherst. |

|

James Wolfe |

At that time, military appointments were based largely on favouritism, politics or pelf - not ability. One's rank depended on whom one knew, not what one knew. Contrary to this well-established custom, Wolfe's commission was awarded solely on the basis of his superior ability, as demonstrated under fire. This fact and the selection of such a junior officer for such a prestigious assignment, provoked bitter jealousy among the older officers and angry criticism from within the ministry and the military.

|

Wolfe was born in Westerham, Kent, on the 2 January 1727, to Lieutenant General Edward Wolfe and Henrietta Thompson. The elder Wolfe, a large-featured, bluff, powerful person, rose to his important position in the army through his own ability, despite not having wealth and influence. Henrietta, who was 20 years younger than her husband, was tall and slender and considered by some to be a beauty. Her portraits depict her as a commanding figure, with dark hair drawn back from an oval face and beneath her pointed nose, a withdrawn chin. She had fine eyes and a good complexion.

|

|

James Wolfe's Father |

|

|

Henrietta Wolfe, James's Mother |

Wolfe's childhood home was a gabled red-brick Tudor house of 16th-17th century origin, called Spiers. Known today as Quebec House, it is maintained by the state as a historic site. The low-ceilinged, panelled rooms contain memorabilia relating to his family and career and in the Tudor stable block house, there is an exhibition about the Battle of Quebec. James decided from an early age, that he would take up, "the profession of arms." He was destined to be a soldier, because fighting was in the family. His father had fought under the great Duke of Marlborough and his great-grandfather, grandfather, uncle and only brother, George, were also military men.

|

|

James Wolfe's Birthplace at Westerham |

In 1741 at the age of 14 Wolfe, received his first commission as second lieutenant in the marines. It arrived in a large, brown envelope marked: "On His Majesty's Service." On the very spot where Wolfe received word of the appointment, his friends later erected a stone monument bearing the words:

"This spot so sacred will forever claim

A proud alliance with its hero's name."

Though Wolfe appearance was plain in the extreme, he possessed not only ability and force of character, but the energy and magnetism of a born leader. This was of vital importance at that time because the commander-in-chief not only planned the attack, he led and inspired his troops by being front and centre on the field of battle.

Wolfe was characterized by his coolness and courage under fire and he was found wherever England's wars took her troops. In every engagement he distinguished himself and his rise through the ranks was rapid. When fighting the French at age sixteen, his horse was shot from under him, when it took a musket ball in the body. His gallant behaviour on this occasion, received the official thanks of the commander-in-chief. He fought at the savage, Battle of Culloden [***] and at the age of twenty-two, became a lieutenant-colonel of the 20th Regiment with full command and the responsibilty.

|

|

Battle of Culloden (1746) by David Morier [****] |

Wolfe described himself as the, "military parent" of the whole regiment. He took his parental duties very seriously, by studying the needs of each man and taking wide-ranging interest in the welfare of the common soldier. No detail escaped his notice and no concern of the men was too trivial for his attention. He encouraged the men to participate in sports, hunting and fishing and without one act of inhumanity, he fostered great regularity and exactness of discipline into his corps.

He worried that he might become the type of officer who was,

In His Own Words,

"a mere ruffian, proud, insolent, intolerable."

,/p>

To ensure this did not happen, Wolfe developed a passion for self-improvement. While other officers "lolled on pleasure's downy lap," he cultivated self-improvement and the arts of war. In his early twenties, he hired a tutor in mathematics, one in Latin and another in French, and spent hours slaving away at his studies. In a letter to his mother, he reviewed his daily routine. "I am up at seven and fully employed till twelve. I don my dress uniform and visit, then dine at two. Later I ride, fence, dance and have a master teach me French." Military tactics, higher mathematics and French, were his chief interests and he was anxious to go to the Continent and study engineering and artillery.

|

|

Portrail of James Wolfe by Brigadier George Townshend, 1759 [McCord Museum, Montreal] |

Wolfe was filled with excitement and pleasure at his appointment. Here at last was the opportunity he had been waiting for - an army to command, a campaign to organize, an enemy to defeat. All day long during January he wrote letters, studied maps and manuals, drew sketches and diagrams and studied French dispatches that had been stolen from a French ship. Among the letters, was one to his mother.

"Dear Madam [it began as always]

The formality of taking leave should be as much as possible avoided, therefore, I pray this method of offering my good wishes and duty to my father and to you. I shall carry this business through with the best of my abilities. The rest, you know, is in the hands of Providence, to whose care, I hope your good life and conduct will recommend your son. Saunders talks of sailing on Thursday if the wind comes fair. I heartily wish you health and happiness, the the easy enjoyment of the many good things that have fallen to your share.

My best duty to the General.

I am, dear Madam,

Your obedient and affectionate son,

Jam. Wolfe

London, Mon. morn."

Wolfe thought of nothing but the conquest of Canada, and the chance for fame, perhaps, immortality. "Those who perish in their duty and in the service of their country, die honourably."[**] While Wolfe led his troops with complete lack of regard for his own life, which he often risked needlessly, he showed great concern for his men and this earned him their undying loyalty. Early in his career he ordered his officers to,

In His Own Words

"Attend to the looks of the men, and if any are thinner or paler than usual, determine the reasons and take proper means to restore them."

Some officers scoffed at their new major's methods, but his policies were well proven on the Plains of Abraham. Wolfe trained his men to such a state of efficiency, that they became a 'show regiment' of the army, paraded out whenever a distinguished personage wanted to see the British Infantry at its best.

|

|

James Wolfe |

Wolfe's army was to consist almost entirely of regular troops, including ten battalions of regulars who had served for some time in North America. A substantial number of men from the American colonies were also included. As with most British officers, Wolfe was not interested in having Americans included. He dismissed them "as the worst soldiers in the universe," complaining that they were too influenced by "the Pow-wow, paint and howl." This negative conception of colonial troops reflected their lack of training and discipline, for unlike regulars who had experienced months if not years of service, they enlisted for a single campaign rather than for many years of service. Training and discipline were to ensure the ranks would not break in battle. European combat called for two close armies to discharge musket fire directly at each other. Firing and reloading under combat conditions required nerve. Speed of fire was important and a well-trained soldier could fire up to five shots a minute. A poorly trined soldier might flounder and flee. In such circumstances, colonials often looked like sorry soldiers indeed. The madness of standing still and facing fire from a few feet away was not for them. Colonials were more likely masters of the woods, who fought skirmishes effectively.

Despite Wolfe's distinguished reputation he did not cut a imposing form. He was thin, clumsy and chinless and with his incongruous face and figure he resembled more a sissy than a soldier.. Wolfe had a pale complexion, a receding chin and forehead, an upturned nose and irresolute mouth. He had flaming red hair, and in contrast to the custom of the time, Wolfe never wore a wig. He preferred tying his own hair in a pigtail fastened with a ribbon or a buckle. He was tall, gaunt and awkward, with narrow shoulders, a slender body and long limbs that exaggerated his lanky, six-foot-three-inch frame. Like Pitt, he was chronically sick, forever fighting his own weakness. His hero's heart was encased in a frail frame, because he had inherited the rheumatoid condition of his father. Wolfe, who had a habit of picking nervously at his cuffs with his long, tapering fingers, was reserved, stubborn, easily angered and often acted or responded impetuously without thinking.

In His Own Words

"It is my misfortune to catch fire on a sudden, to answer letters the moment I receive them. The next day, perhaps, would have carried more moderation with it. Every ill turn through my whole life has been caused by this haste and quick resentment. It proceeds from pride."

Wolfe was a sickly boy whose mother dosed him regularly with her own recipe for consumption, made from green garden snails and sliced earthworms. Little wonder he remained sick. With his younger brother Edward - Ned - he raced through their old house, with its winding staircase and hidden doors leading to secret passages. In the evenings by the huge fireplace, he heard stirring stories about war told by brandy-smelling colonels with grim faces. His life was determined for him. He would be a soldier and die for his country in the most glorious manner conceivable. His forecast became fact - he became the hero he hoped would be his fate.

|

|

Wolfe was Not an imposing figure. |

Like Pitt Wolfe had a vision of his destiny. He would lead masses of soldiers, brilliant red figures marching in perfect formation towards ordered death and regimental glory. Wolfe's military genius and determination made him ambitious, while his wretched health, dread of the sea and longing for a life at home held him back. He was a martyr to seasickness and a man with an endless run of illness. He loved flowers and his dogs and carefully arranged for their care in his absence, "especially my friend Caesar who has great merit and much good humour." Wolfe loved children and when he became engaged to Katherine Lowther his fondest wish was to marry and watch with her as their children grew up in a snug little cottage in peaceful Westerham. When he departed to capture Quebec he abandoned these dreams for there was little likelihood he would ever see her again. He left with a lock of her hair in a miniature portrait of her around his neck.

Wolfe' persistent poor health often caused him to become deeply depressed. This sometimes clouded his judgement and led to passionate outbursts. He freely admitted he was "in very bad shape with the gravel and rheumatism, but I had much rather die than decline any kind of service." Those who knew him declared that "nothing but the clear, piercing, azure-blue eyes bespoke the spirit within." This was no normal British general. It was said of him that he faced death with "gallant despair" knowing his time was short in any case.

During the last two weeks of May in 1759, Louisbourg was a beehive of military activity. Wolfe's 9000 redcoats along with the 18,000 sailors and marines who manned Admiral Saunder's mighty armada were preparing for the contest to come in New France. Wolfe drilled his soldiers, each day having the men practice the demanding task of climbing down rope ladders on the sides rolling ships into flat-bottomed boats tossing about on the waves, then battling the pounding surf that savaged the shore nine days out of every ten, they assaulted the rocky beaches. Shore landings were practised again and again until the soldiers and sailors had mastered the drill. Signal officers and semaphore men memorized and rehearsed dozens of flag combinations used to send orders. Gun captains put their batteries through endless rounds of practice.

|

|

Departure for Quebec |

Finally with the training finished, landing barges were hoisted up and the ships made ready to depart. The time had come to strike at the very hear of New France. The "Admiral proposed sailing on the first fair wind." With drums beating, bugles blaring and flags wafting in the wind, regiment after regiment marched down to the beach to board. "Our troops are good," declared Wolfe, "and if valour can make amends for the want of numbers we shall probably succeed."

All ranks were in the highest spirits knowing that they were the picked force chosen for the decisive work of a major campaign. Excitement was high. Great things were expected at Quebec.On June 4th, 1759 three guns were fired from the fortress. The signal to weigh anchor and make sail shot up the halyard on the flagship Neptune. Within the hour great clouds of canvas caught the wind and with white sails billowing in the brisk breeze, one hundred and forty-one ships left Louisbourg. The fleet, which represented a quarter of the Royal Navy, was the greatest flotilla ever to sail across the sea. The hills about the harbour echoed to the cheers of the men who thronged the decks while in comfortable cabins below officers sipped wine and toasted the king and his colours."The British flag on every French fort, port and garrison in America."

|

It was said that the first article of an Englishman's political and military creed must be, "That he believeth in the sea." When your country is an island that is a pretty sound suggestion. Britain's navy, which for centuries was the mainstay of its defence and major means of offence, was called on to conquer once again. The formidable invasion force was dispatched to Quebec to drive France from the continent forever. It included three ships-of-the-line - the great wooden-walls of England. One was Admiral Saunders' ninety-gun Neptune, a towering three-decker castle of wood and sail containing a crew of 750 men. There were 22 smaller ships-of-the-line, each armed with fifty cannons as well as assorted frigates and sloops. In total the fleet had a fire power of some two thousand guns. The convoy also contained 119 transport supply and ordinance vessels along with fire-ships and bomb-ketches. The field artillery contained a pair of 8-inch howitzers and the biggest brass and iron cannons of the time.

Wolfe assumed they would be successful and assured his superiors the coming conflict would be a conquest. "Great sufficiency of Provisions & a numerous Artillery is provided and from the known Valour of the troops the Nation expects success. These Battalions have acquired reputations in the Louisbourg campaign & it is not doubted but they will be careful to preserve it. From this confidence the General has assured the Secretary-of-State in his letters that whatever may be the event of this Campaign, His Majesty & the Country will have reason to be satisfied with the Army under his Command. The General means to carry the Business thro' with as little loss as possible & with the highest regard to the safety and preservation of the Troops; to that end he expects that the men work cheerfully and diligently without the least unsoldierly murmurs of complaints & that his few but necessary orders will be strictly obeyed."

What a magnificent and stirring sight the mighty fleet made, a kaleidoscope of movement and markings as the dazzling array of flags and pennants fluttered and shimmered in the summer breeze. Great excitement and the explosive sight of military might thrilled everyone with feelings of confidence and anticipation. By noon on the 6th the last of the mainsails had melted into the horizon and vanished into the immense spaces of the sea. Their destination: the key to all Canada - the Citadel of Quebec. The armada, whose swelling sails flecked the sea, sought not just to impede the power of France in America but to eradicate it. Stretching fifty miles along the coasts of the gulf and the river this immense flotilla made its way to the fortress on a rock called Quebec where a man named Montcalm awaited the showdown he was sure would come.

While France sent little in the way of aid to their soon-to-be-besieged colony, its Minister of War expected a miracle from Montcalm. He had written to the general in February 1759. "I am confident that you will not disappoint me and that for the glory of the nation, the good of the state and your own preservation you will go to the utmost extremity rather than submit to conditions as shameful as those imposed at Louisbourg the memory of which you will wipe out."

|

|

James Wolfe |

The last privately owned portrait of James Wolfe, the British military general who conquered the French on the Plains of Abraham, is now in Canadian hands. Bonhams says an unnamed Canadian collector bought the portrait for about $635,000 at its auction of old master paintings in London earlier this week. It had been expected to fetch between $126,000 and $190,000 and was sold by a British family who acquired it around 1850. Bonhams believes it has never been owned by a Canadian before.Bonhams describes it as a posthumous depiction of Wolfe as a young man at the Siege of Quebec in 1759 and appears to be the only version to depict Quebec.The auction house dates the work to between 1760 and 1780 and attributes it to Joseph Highmore, a British painter also believed to be responsible for a portrait of Wolfe in the National Archives of Canada. Wolfe led the British assault on Quebec in 1759, culminating in the Battle of the Plains of Abraham where he was mortally wounded. His victory proved to be a deciding moment in the conflict between France and Britain. “It was particularly exciting to handle a portrait of such historical importance,” Andrew Mckenzie, head of Bonhams Old Master Paintings Department, said in a release. “Among my early schoolboy memories is being taught about Wolfe's celebrated victory at Quebec. Rarely does one have the opportunity to sell a major portrait of such a momentous historical figure.”

[*] This anecdote was first mentioned in print by Lord Mahon in his, History of England, published nearly one hundred years later. He heard the account from a friend, Thomas Grenville, who died in 1846 at the age of 92. Grenville claimed to have been told the story by Temple. The truth of tale is challenged, because Pitt's brother-in-law, Temple, was known to be an accomplished and malicious liar. Doubtless, the tale was made taller in the telling. [**] "The desire for glory clings even to the best of men longer than any other passion." Tacitus [***] Culloden: The bloody and lopsided encounter at Culloden has been called the most emotive episode in British history. Earlier on the redcoats stealed themselves for the first taste of action. Undergoing their baptism of fire and enveloped in dense clouds of smoke from the ignition of black power weapons, many turned tail and ran at the first sight of the broadswords and tartans. Later, however, their harrying of the rebel Highlanders in the heartland was brutal and ugly. In the confused mele, their retreat escalated into rout as the human and equine avalanche descended on them. The lanky 15-year old Wolf, now resplendent in scarlet coat, yellow facings and the gold lace of an ensign, was 'Hangman Hawley's' young, brusque henchman. Like all British officers, Wolfe was notoriously touchy about his reputation. [****]"After 1688 when James VII of Scotland and II of England was replaced by his daughter, Mary II and her husband William of Orange, many who refused to swear allegiance to William and Mary were tried for treason and "attainded." Some were executed and some sent into exile. They were punished by Acts of Attainder - losing their rights and property. This process continued after the Jacobite rebellions of 1715 and 1745. The blood of many of the rebels was deemed "corrupt," they had their property confiscated and were exiled to North America as indentured servants. Now the Scottish Parliament is taking steps to have the stigma associated with support of the Stuart cause removed. It has been asked to back a petition that demands the Westminster Parliament overturn the Acts of Attainder and clear the names of Jacobite family descendants and remove this "historical discrimination." [National Post 15 August 2009]Copyright © 2013 Website Administrator