foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

THE CLASH OF CROWNS

Great Britain and France are the closest of allies now, but for countless years they were the best of enemies and fought each other bitterly for any number of reasons. One of their conficts resulted initally from relatively minor clashes in North America.

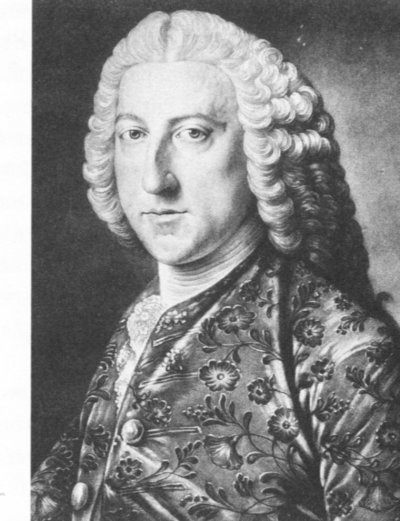

In the middle of the eighteenth century, the French controlled vast areas of the eastern American continent that stretched from the mouth of the St. Lawrence River across the region of the Great Lakes, down the courses of the Ohio and the Mississippi Rivers, as far as the outlet of the latter mighty river into the Gulf of Mexico. French forts along this frontier barred the western expansion of the English colonists. The colonies of the English king, George II, which were confined to the Atlantic coast, greatly outnumbered the colonists of France's King Louis XV.

|

|

George II |

|

|

George III |

|

|

Louis XV |

The rivalry, that eventually ranged over North America, Europe and India and lasted from 1756-63, was called the, Seven Years' War.

History records the fall of frowning battlements.

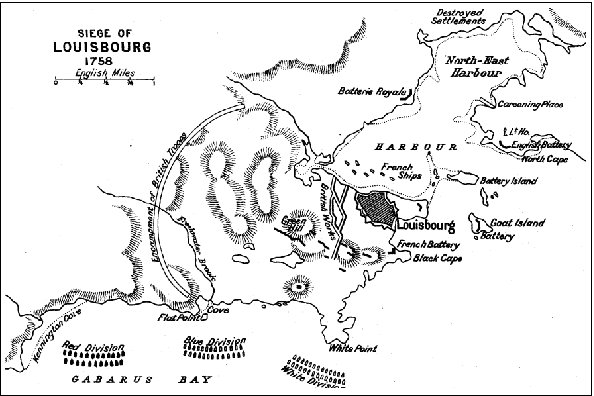

Fall of Lousibourg

|

|

Map of Louisbourg |

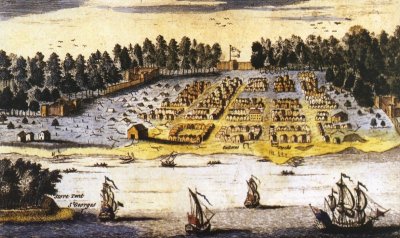

The beginning of the fall of France's North American continental empire was directly related to the loss of Louisbourg, the Dunkirk of America.

Louisbourg was acclaimeded as the strongest fortress in America, a walled city without a peer in the new world. It was an elaborate, fortified, garrison town, created to maintain the French Atlantic fleet, protect the French fishery and serve as a focus for future settlement. Its great fortress was located on a narrow ridge of moorland and marsh, the sea itself serving as a moat. On the landward side, there was a ditch eighty feet in width and stone walls, with their four great bastions rising thiry feet into the air. The harbour was guarded by batteries on one of the islands as well as on shore. Inside the town, some five hundred regular soldiers, together with the militia, provided a stout defence, at least on paper.

Situated on the fog-infested rocky southeast shore of Ile Royale, the enormous bastion and the fleet it sustained, guarded the Gulf of St. Lawrence - key to the gateway to the heartland of the continent. The citadel served as a shield for New France and a sword against New England. Because of its seeming invincibility, it was known as the Gibraltar of North America. However, it was only as strong as brick and stone could make it. Its towers and battlements, rising against the murky background of rough terrain and swampland, were according to one historian, "an incongruous expression of artificial grandeur." Behind its imposing exterior, there were serious weaknessess. Its batteries were located poorly in places, it attracted few settlers and it never became a thriving commercial centre.

This drear, deserted, barren land, where some four or five thousand lived, was thoroughly hated. It was hated by the French government for its drain on their resources. It was hated by the British government because it cut into their overseas communications. It was hated by American colonists because it was an ever-present menace to their grand plans for the future. It was hated as well by those who manned the fortress. Its harshness was felt most keenly by the soldiers who lived in cold, overcrowded barracks and subsisted on inadequate rations of fish and bread. The posting was not popular with French officers either, because the frigid winter months made it a depressingly desolate base. Life, however, was made bearable by its officers, wealthy merchants and royal officials, with fine dinners, garrison balls, games at the gambling table and the occasional duel. In the summer when the air was clear and the rolling surf sparkled in the warm sunlight, life was good.

Louisbourg was named in honour of France's Sun King, Louis XIV. Louis ascended the throne in 1643 when he was 5 years old and ruled until his death at the age of 77 in 1715. Called by some a "high-heeled, periwigged megalomaniac," who seldom stepped down from his lofty pedestal, Louis was christened the Sun King to honour his greatness. He was only five foot five, but his power and personality made him appear much larger. He had excellent manners and never failed to doff his hat to the women he met, whether high or low born. His mind was not as good as his manners. In fact, he had nothing more than good sense, but he had that in abundance and he was every hour a king.

|

|

The Sun King |

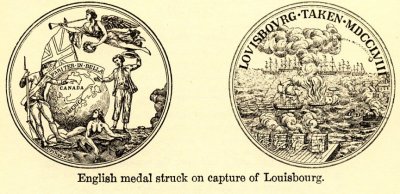

Construction of the fortress was commemorated with a medal bearing the inscription "Louisbourg founded and fortified, 1720." On the obverse side, there was the profile of Louis XV, great-grandson of the Sun King, who succeeded to the throne because his grandfather, father and older brother all died within the period of one year before old Louis XIV passed away.

|

|

Louisbourg Medal (1) |

|

|

Louis XV (5) |

Louis XV was ten years old when work began on the fortress and thirty-five before it was finished. Over the years of its construction, the fortification emerged from the sea mists like some looming monster. When its brooding hulk came into view, all who saw it marvelled at the mammoth bastion, whose ten-foot thick walls rose some thirty feet high behind a steep ditch. While well protected by men, muskets and cannons, the stronghold's first line of defence was the pounding surf on the savage seashore, the menacing moat with which nature had endowed her.

The structure, every brick of which was shipped from France, exhausted the efforts and the energies of numerous engineers and thousands of labourers. It consumed countless livres from the French treasury, the price in today's values amounting to 50 million dollars. Such was the colossal cost of the enormous structure, that Louis XIV "the best informed man in his kingdom," said he expected at any moment to see its towers and turrets appearing over the western horizon.

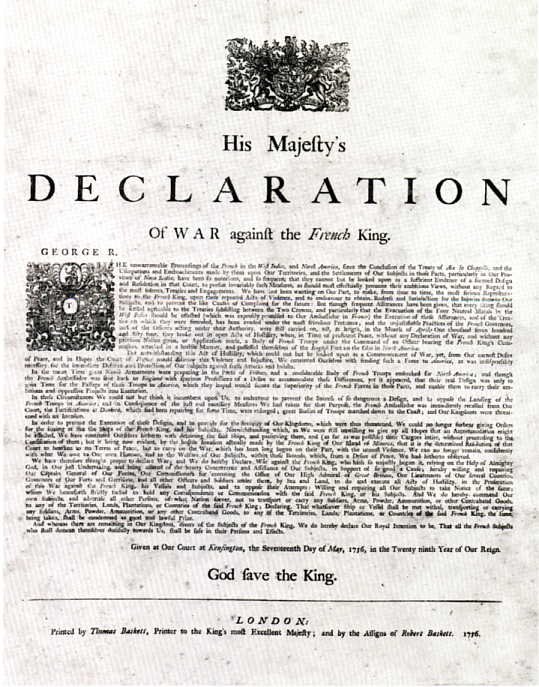

For a long period, dense black clouds hung over England, for its military endeavors abroad were stained by ill-luck and incapacity. During the undeclared war, which had been in effect for two years, Britain was frequently the loser. On May 17 1756, George II finally issued a formal declaration of war against France. The provocative words of the declaration made Britain's views very clear.

|

|

Declaration of the Seven Years' War War 1756-1763 |

"The unwarrantable proceedings of the French in the West Indies and North America since the conclusion of the Treaty of Aix la Chappelle and the usurpations and encroachments made by them upon our Territories and the settlements of our Subjects in those parts, particularly in our Province of Nova Scotia, have been so notorious and so frequent, that they cannot but be looked upon as sufficient evidence of a formed Design to promote their ambitious Views without any regard to the most solemn treaties and Engagements."

By the time this war ended, France would have lost most of her colonial empire.

In the initial stages of this conflict between France and Great Britain, known as the Seven Years' War, the war had been barren of satisfactory results for Britain. It had yielded only a succession of failures and defeats. Britain was frequently bested because of poor generalship, quarrelling colonies and a weak government in London. Disaster followed upon disaster as the drums rolled a dirge of defeats: Fort Necessity; Monongahela the border scourge, Crown Point; Oswego; and the destruction of Fort William Henry. The drumbeat of military routs and retreats, was like a death rattle. The reversals staggered Britain and her future prospects augured little but more gloom and doom. The clouds that hung over the country were dense, black and filled with foreboding.

Then the hour found the man. Brilliant William Pitt, the Elder, became the self-styled "saviour of the British Empire." Bill, who liked his booze alot,was known as a "three-bottle man," when most of the other lords, were "two-bottle men." Pitt did his own thing, (fais ce que voudra). He was a superb orator. He made his reputation in the House of Commons as the " People's Tribune," for he who had the confidence of the great mass of the labouring classes in Britain.

|

|

William Pitt the Elder (1708-1778) |

|

|

William Pitt in Parliament |

Pitt was incorruptible in a corrupt age. He shattered all tradition, while serving as Paymaster of the Forces, by never partaking of public money for which he was responsible. Such honest integrity was most unusual, when corruption in government was common. Golden-voiced, but scorning gold, Pitt's honesty, integrity and inspirational utterances, earned him the enviable sobriquet, Great Commoner. Great but certainly far from common, Pitt became the true founder of the vast British Empire, upon which, it was could be said, until World War II,"the sun never set."

Initially, Pitt served only as Secretary of State, but because of his intellectual power and overpowering personality, the reins of authoriity fell into his hands and he was practically prime minister. Granted the powers he needed, he assumed total responsibility for management of the war. For the next four years, this complex and perplexing figure, towered supreme in British history. Vowing to end the humiliating thrashings England was suffering at the hands of French forces, Pitt employed men and treasure without measure to ensure the total destruction of the French Gibraltar.

|

|

William Pitt, the Elder |

It was towards America that Pitt initially turned. It was natural that his primary focus would be on the great fortress - Louisbourg. It commanded the Gulf of St. Lawrence and no expedition against Quebec - Pitt's ultimate objective - would be safe with this huge bastion in French hands. Should France decide to become aggressive in America, Louisbourg would be the base from which attacks would be launched on the British colonies.

Pitt's policy was to keep France, which recognized Pitt as its most dangerous adversary, busy in Europe fighting the Prussians while he ripped from her grasp the great colonial empire, smashing forever the power of the French in North America. To do the job he dispatched 23,000 regulars. Because Pitt could engage the confidence of British subjects in the New World as he did his countrymen in England, he was able to supplement the redcoats with men from the America. To oppose this impressive British force France grudgingly sent out only 7,000 troops.

Frederick the Great, King of Prussia, whom Pitt was generously funding to fight the French in Europe, said of Pitt,

In His Own Words

"England has taken a long time to produce a great man for this contest, but here is one at last. He is a lofty spirit, a mind capable of vast designs, of steadfastness in carrying them out, and of inflexible fidelity to his own opinions because he believed them to be for the good of his country, which he loves."

|

|

Frederick the Great, King of Prussia |

Pitt became the cornerstone of the cabinet. No man knew more of men and he neither feared nor flattered any flesh. Behind his great intellectual powers was burning enthusiasm, a fierce, forceful intensity of will. He swayed the opposition with a look or contemptuous wave of his hand and quieted criticism from fellow ministers by threatening to resign. He made no attempt to consult or conciliate, but overwhelmed his colleagues with energy, vision, deft decisions and a sure sense of selecting the right man for the task. He astonished his subordinates with his detailed knowledge of minor matters, and his all-inclusive understanding of the broad scope of the war. For four years he was supreme. " He inspired the nation. The ardour of his soul had set the whole kingdom on fire. It inflamed every soldier who dragged a cannon up the heights of Quebec. He imparted the commanders he selected with his own impetuous, adventurous and defying character." Officers and soldiers alike knew that with Pitt in command failure might be forgiven, but wavering never would. Such was the spirit of Pitt.

The idol of England, the terror of France and the admiration of the civilized world, Pitt resolved to make England pre-eminent. This fiery, forceful, resourceful leader dedicated himself to that end with fanatical zeal. Determined to command and conquer and never count the cost in blood or gold, he lavishly looted the Treasury to recruit additional regiments. Using new naval plans he completely re-built and re-organized Britain's mighty waterborne bastion - its great fleet.

|

The frequent appearance of French privateers off the New England coast helped convince the normally divided and difficult American colonies to cooperate with Britain in its fight with France. So too did the promise of liberal compensation to those colonies agreeing to contribute troops. "As a bounty and encouragement to them" to carry on the struggle, the British government distributed some hundred and twenty thousand pounds among ten of the colonies.

|

Pitt assumed direct control over every important detail of the struggle. His crowning virtue as a minister of war was his practice of controlling operations everywhere without interfering with them anywhere. His persistence, restless energy and resolve eventually won the day. Holding history in his hands, he presided over the elimination of France as a colonial power in North America and in so doing captured a continent.

The magnificent fortress of Louisbourg looked impregnable with its three gates, its eight bastions and its two miles of stone and mortor walls over thirty feet high with embrasures for 148 guns. It was ideally located and boasted a fine harbour. Perched on a promontory it commanded a view of the Atlantic and of Cape Breton Island. Any ship navigating the half-mile passage to the large harbour faced sixty-nine guns mounted on the island Battery and the Royal Battery. In the New World there was never another like it nor would there ever be again. Throughout the civilized world men spoke in wonder about the great fortress on the Canadian shore.

In his eagerness to engage the best of Britain's military leaders Pitt ignored traditions and seniority and promoted younger, first-class military men over more senior officers. Pitt knew an incompetent general could ruin a good plan so on land and sea he placed his personally selected officers in positions of authority. Colonel Jeffery Amherst, an energetic and resolute soldier, was given the rank of major general and placed in over-all command. In Amherst Pitt had chosen a logistical genius, a methodical, very cautious, some said overly-cautious, general, but two things stood out in his favour. He avoided any disasters by knowing how to feed, supply and move an army and he was very generous in his praise of his brilliant brigadier, James Wolfe.

|

|

Jeffrey Amherst |

James Wolfe, conspicuous by a dashing gallantry, did not escape the eye of Pitt. Ardent, head-long and devoid of fear, Wolfe was rash, almost fanatical in his devotion to military duty and reckless of life when the glory of England was at stake.

|

|

Major General James Wolfe |

Pitt found a capable admiral in the Hon. Edward Boscawen.

|

|

Edward Boscawen |

In 1748 the British made plans to build a comparable fortress to neutralize the menace of Louisbourg. The location they chose was on Chebucto Bay on a hill overlooking the harbour now known as Citadel Hill. It was naamed Halifax after the Earl of Halifax who had suggested its construction. Settlers from England rather than the 13 Colonies were enticed to travel to the fortified town by offers of free transportation, free food for a year and military protection. Lieutenant Colonel Edward Cornwallis was appointed governor of Nova Scotia and with 2576 settlers set sail for Halifax in 1749.

|

|

Halifax Under Construction 1749 (Charles Jeffreys) |

|

|

Halifax Harbour from a map published in England in 1750. |

In 1755 Halifax bristled with British arms for its finest military leaders were enjoying a leisurely meal at the Great Pontiac Hotel before setting off to fight the French. At this grand hotel overlooking the city's harbour General Amherst and his officers lauded the coming assault on Louisbourg. Forty-seven guests were served by fifteen attendants and entertained by ten musicians. Enjoying fine foods and the juice of the grape Pitt's men made merry before launching their attack on the great French fortress.

|

|

Lord Jeffery Amherst |

|

In their midst was a man named Wolfe, a slight, pale, melancholy young man of thirty-one who had been plucked from the ranks of the obscure young lieutenant colonels to be third brigadier under General Jeffrey Amherest in Pitt's planned assault on Louisbourg. Wolfe had seen war. He had learned his cruel craft in a bloody school that included slaughtering rebellious Scots at their Highland uprising in 1745. He was to put that brutal training to good use in the coming war with France.

Wolfe, the self-confessed "worst mariner on the whole ship" had land in Halifax from the Princess Amelia on May 8. It had taken him some time to recover from the eleven-week voyage from England to Halifax. On occasion the seas ran high and the winds were wild and on other days the sea was serene. In a letter to a friend, Wolfe confided, "From Christopher Columbus's time to our days there has never been a more extraordinary voyage. The continual opposition of contrary winds, calms and currents baffled all our skill and wore out all our patience." The fleet had sailed from Spithead on February 14.

|

|

Life Portrait of James Wolfe, circa 1750-55 |

Admiral Edward Boscawen's fleet consisted of 23 ships of 50 guns and over, mounting in all 1684 guns and was supported by 18 frigates.

|

|

A British Frigate |

Amherst, whose army numbered 12,000, was assisted by various brigadiers one of whom was Wolfe. Wolfe's magnetic personality and professional ambition gave him predominance in council as well as in execution of projects, a prominence neither his experience nor seniority entitled him.

There had been signs of the enemy since the first signs of spring. Sails were seen hovering on the distant sea, appearing and disappearing in the gales and mist as the ships cruised off the mouth of the harbour. On May 28, 1758 the Boscawen's fleet was ordered to sail and the guns to fire. The convoy left for Lousibourg and five days later the southeastern horizon was white with a cloud of canvass. Boscawen sailed into Gabarus Bay. The sea was rough but in the afternoon, Amherst, Lawrence and Wolfe with a number of naval officers reconnoitred the shore in boats, coasting for miles and approaching as near as the French batteries would permit.

The French fortress was astir early, its defenders anxious to get a glimpse of this dread demolishing armada heralded by white clouds of canvas. As usual along this rugged coast, rain, fog and running surf made it impossible to venture close to shore immediately. For a time the great flotilla was hidden behind a curtain of dense fog and for two days the vessels tugged at their anchor cables in the bay. Then a light Atlantic sea breeze withdrew the misty drapes and revealed the mighty fleet closing for the death-grip on its quarry.

|

|

|

Besieged Louisbourg |

|

|

British Fleet Entering the Harbour of Louisbourg |

|

|

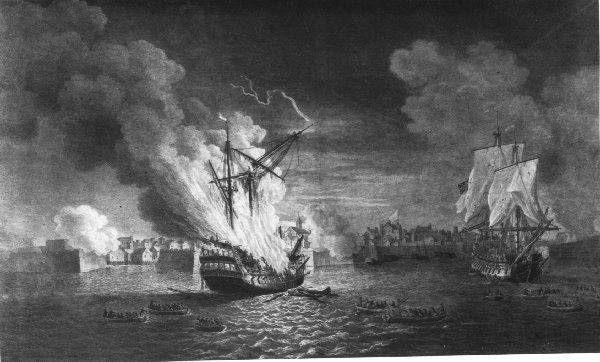

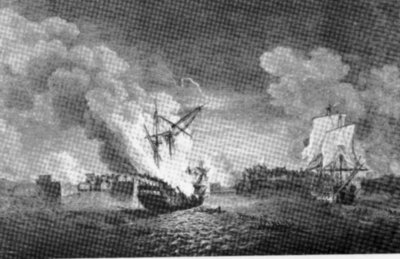

Royal Navy Capture and Destroy French Warships Guarding Louisbourg. [No.21] |

The Governor of Louisbourg, Augustin de Boschenry de Drucour, a gallant and experienced officer, had decided to man the shore defences in order to meet and master the enemy on the beaches. Trenches had been dug and batteries erected at Cormorant Cove, the likeliest spot for the assault. Wolfe waited on the Neptune ready to lead the Grenadiers, Highlanders and Light Infantry to spearhead the assault. At 4:00 a.m. under cover of a naval bombardment, three assault brigades designated with red, white and blue flags assailed the rugged coastline. Facing a storm of French grape and musket fire, the attackers also fought fog and the pounding surf that masked beneath its foaming might treacherous rocks. As English and French ships answered cannonade with cannonade, British soldiers climbed over the sides and crammed into the landing craft and set off to assault the beaches.

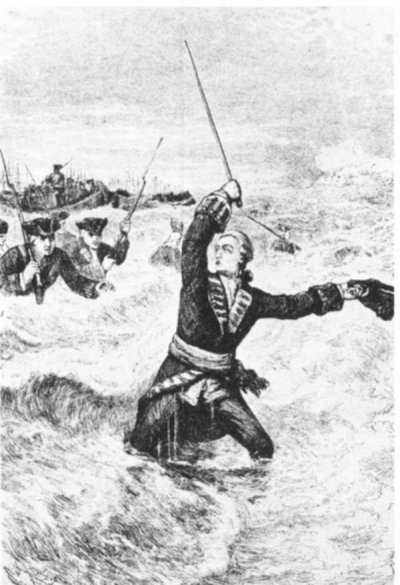

The French in trenches were provided with spare loaded muskets. They wisely held their fire until the boats were close in shore and then poured such a deadly fire on them it appeared landing would be impossible. It looked as if Wolfe's first experience in command was to be a disastrous failure. Despite his eagerness and the courage of his men his advance seemed decisively checked. He waved and shouted but it was impossible to know whether he was urging his men on or ordering a retreat. Wolfe was a bold and daring man but no rash one. Retreat it was and his boats turned to the open. Then came the break. Three boats to the right of Wolfe's forces drifted or rowed towards the east and there found themselves sheltered from fire by a ridge. Nearby was a small space of sand among the rocks on shore and they landed on it. Wolfe saw three boats ground ashore and decided to press home the advantage. In the face of a deadly rain of grape shot and merciless musket fire from nearly 1000 French soldiers that peppered the water they rowed ashore.

|

|

Attack on the French Fleet at Louisbourg |

|

|

Well Executed Amphibious Assault on Louisbourg. |

If fame does, in fact, sometimes lack a fine sense of justice in choosing her favourites, she made no mistake in her choice of Wolfe. The cane flourished above his red head, pointed to the inlet, lifted again and swept forward. The great commander had instantly recognized and seized the opportunity. His column swung inshore before him, the flashing oars churning up the water. His attack was a direct frontal one on an impregnable position. His red-flagged spearhead column, the smallest in numbers but stoutest in Highlanders and grenadiers, earned accolades that day for its daring. In showers of spray and plumes of smoke boats splintered and overturned hurling men into the sea. Others became entangled and smashed on the rocks, their approach made hazardous by jagged rocks and a boiling surf. Some were shattered by cannon shot while others turned over in the surf throwing redcoats into the angry sea where they gulped and gasped and sank in their heavy uniforms. Others held out oars and threw ropes to the spluttering, choking soldiers, peppered by French sharp-shooters as they tried to pull them back on board only to be washed off their feet by the cascading water thrown up by the exploding shells. Wolfe stood miraculously upright as cannon shot thumped past him and smashed the flagstaff.

|

|

Wolfe Wades Ashore |

|

|

Follow me, Men! |

Despite the swampings the attackers poured ashore. Men leaped into the water and those who kept their feet waded in while those who fell were drowned or crushed by the heaving boats. Wolfe with his long, lank, red locks tied neatly behind his head leaped knee-deep into the surf armed only with his cane, waded ashore and clambered up the twenty-foot crag. With three months of seasick agony behind him he was triumphantly back on shore sniffing blood and gunpowder.

As soon as he had gathered a few hundred men around him, Wolfe ordered them to fix bayonets because their muskets and powder were soaked. Then the charismatic commander led a charge across a short spit of land that divided them from the French emplacements. With the view obscured by the smoke from their guns, the French never saw what was happening until they found themselves facing Wolfe's bayonets. Only then did they realize that the British had established a bridgehead. Fearful of being cut off they panicked and fled without spiking their guns, chased all the while by the exultant British. Slashing a gash in the French line the redcoats rolled back the whitecoats who sought safety behind the fortress walls.

|

|

A Whitecoat - Soldier of Le Regiment de la Reine, 1759 |

|

|

A Redcoat - British Artilleryman, 1759 |

Wolfe's orders always reflected the care and anxiety he showed for the welfare of his troops and his even-handed, considerate manner motivated the men. His fearlessness in the face of action inspired them. He was fair in assigning duties and quick to reward with rum and fresh fish those who worked with a will. Wolfe's reputation spread from his detachment throughout the army and even among the French. Monkton, another brigadier, recorded this in his journal. "Wolfe was the most vigorous to animate the execution of the attack and began it with the same bravery, activity and judgement the whole army have been witness to."

Battling heavy fog and high waves the amphibious task force burst upon the invincible bastion. Once the big guns were ashore and set up there was no question as to the result. It was only a matter of time. The siege was a typical European operation - the first of its kind in America. Guns of old antagonists confronted each other, flaming and thundering at ranges that narrowed from a mile or so to a few hundred yards. Weight of metal at first favoured the defenders but that did not last long. Closer and closer the big British guns drew on all sides, the ramparts of the fort flattened by cannon balls fired from two hundred yards. It might take all summer but the fort would be reduced to rubble. Meanwhile sustained red hot shot from mortors and cannons rained down upon soldiers and civilians alike, the tongues of flame from fire bombs called carcasses lighting the sky before falling on the terrified defenders defenceless in the face of such a conflagration.

|

Louisbourg was alight with the glow of flames by night and white clouds of smoke by day. A Frenchman's diary recorded this despairing entry. "Not a house in the whole place has been spared the force of their cannonade firing the buildings faster than fire crews can put them out. Between yesterday morning and seven o'clock tonight from a thousand to twelve hundred shells have fallen inside the town, while at lest forty cannons have been firing incessantly as well." In additon to the pounding of the siege guns, exploding mortor shells savaged the population, the hollow, cast iron shells filled with exploding charges that scattered iron fragment in all directions. As the enemy drew nearer they added to the frenzy with fiery incendiary projectiles that torched what was left of the town. The cries of the injured and dying, of bellowed orders and the crashing and splintering of exploding missles against the walls comprised a hellish cacophony. For civilians and soldiers alike it was a terrifying time and as night settled over the ruins and the rubble the town took on a grim aspect.

|

Drucour battled back as best he could but he was outnumbered four to one. Even his wife, Madame Brocour, a woman of heroic spirit, walked the Louisbourg ramparts daily in full view of the enemy. She also shouldered arms and fired cannons, her very presence in their midst motivating the men to greater effort. General Amherst was duly impressed and sent her two pineapples freshly received from the Azores with an appropriately gallant note. Madame replied with a crate of champagne which prompted more pineapples and some butter. Old world gallantries could not save the fortress being bombarded relentlessly by British batteries.

On one day alone a single artillery unit of six guns blitzed the fort with 600 cannon balls. The assault silenced the French artillery so effectively a British officer commented, "The French cannons seemed more like minute guns at a funeral than a defence." By the 23rd of July British General Jeffrey Amherst said the defenders were reduced to firing "all sorts of old Iron Nails on every occasion." One eyewitness recorded that the shelling caused the surgeon to tremble as he amputated a limb. "Cries of 'Gare la bombe!' resulted in him leaving his patient in the midst of the operation lest the surgeon share his fate." Inexorably as the crash of cannon and the rattle of musketry rose to a crescendo the iron rings around Louisbourg tightened like the crushing jaws of a giant vise.

The defenders fought fiercely but denied food and ammunition by the blockade defeat was inevitable. One after another French guns fell silent, knocked out by direct hits or silenced by the lack of ammunition. Weakened by scurvy, want of fresh meat and mute muzzle-loaders the ramparts were overrun. With little in the way of weapons but soldiers' breasts, the French asked for terms. Despite the easy aspect of pineapples and wine, Amherst's terms were tough. Faced with the demand for complete surrender within an hour, Drucour sought better conditions. The terms stood and the siege persisted. A second entreaty for terms brought a sterner retort: Complete surrender, yes or no, in half an hour. Amherst's demands enraged Drucour whose defiant reply was that he would fight on to the end.

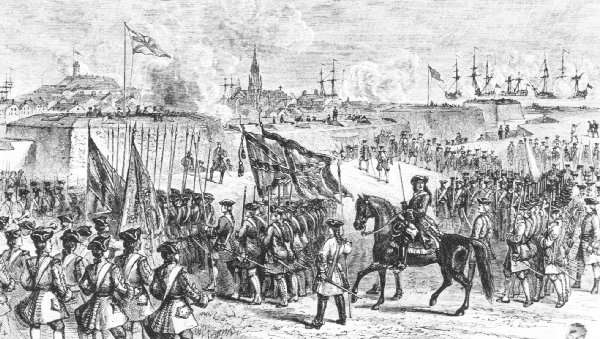

Saner heads were to prevail. Pressed by the beleaguered inhabitants to spare them more death and destruction, Drocour relented and dispatched a second messenger after the first bawling loudly as he raced, "We accept! We accept!" With the declaration "We accept the surrender terms," the dauntless defenders watched despairingly as for the last time the golden lilies of the fleurs-de-lis fluttering proudly atop the battered bastion was hauled down and replaced by the white flag of capitulation. The fort's defences broken, "the whole was a dismal scene of total destruction." When three companies of grenadiers took possession of the Dauphin Gate, the French garrison drawn up on the Esplanade flung down their muskets "and marched from the ground with tears of rage." Drucour and his lady dined with Amherst on board HMS Terrible.

The governor's gallant defence lasted from 7 June to 26 July. It gained time and maintained Montreal and Quebec for another season. |

General Amherst had complete cooperation with Admiral Boscawen from the landings onward. The assault on Louisbourg was an amphibious operation requiring the well-coordinated conduct of warfare where land and sea met. To launch a military operation from the sea required expertise that was more than simply the sum of military and naval skills. The tough, successful, amphibious offensive was the result of perfect co-ordination and co-operation between blue-coated marines and red-coated regulars. The joint navy-army attack by sea and land had defeated the French garrison.

|

|

Royal Navy Commander 1756 |

In Wolfe's Own Words

"the Admiral and the General carried on the public service with great harmony, industry and union."

With the loss of only 195 British lives the star-shaped stronghold had fallen after a forty-six day siege. The impregnable citadel yielded to Amherst's army on the 26th of July, 1758. Its surrender severed the lines of communication between France and her St. Lawrence possessions and opened the sea lanes to New France. The single sword held over British transatlantic shipping was now sheathed. The keystone of the arch of French power in America had been shattered. The terms of capitulation required the French to yield the whole of Louisbourg, Cape Breton and the Isle St. Jean now known as Prince Edward Island along with all the public property they contained. The British demands included the following note.

Sir:

We have the honour to send Your Excellency the signed articles of Capitulation. The Lieutenant Colonel has spoken on behalf of the people of the town. We have no intention of molesting them and shall give them all the protection in our power. Your Excellency will kindly sign the duplicate of the terms and send it back to us. It only remains for us to assure Your Excellency that we shall seize every opportunity of convincing you that we are, with the most perfect consideration, Your Excellency's most Obedient Servants.

E. Boscawen, Admiral

J. Amherst, Commander In Chief

|

|

The Surrender of Louisbourg |

The ardent and indomitable Wolfe had been the life of the siege. His action was decisive and Louisbourg's fall was attributed largely to him. News of his lustre as a leader enraptured the British public and attracted the attention of government officials. He was an unlikely hero. Ashore he was often a virtual invalid, while at sea every surge of the ship made him miserable. To a friend before the battle he confided

In His Own Words

"I have thrown myself into the American war, though I strongly suspect the sea passage threatens my life, and my constitution will no doubt be ruined."

Despite his fears and infirmities Wolfe's fervour as a fighter was extraordinary. He had given spirit to the siege with bold offensives guided standing in the stern of a barge scanning the shore for suitable landing locations. It was his leap into the surf among his men, his appreciation of their every effort and his tireless activity that made the red-coated regulars almost invincible. Despite harsh comments of associates and some unattractive aspects of his character, Wolfe was a great leader and the results at Louisbourg were due in no small measure to his inspirational presence.

Wolfe himself was critical of the operation. He condemned the engineers as "ignorant and inexperienced" and called the overall conduct of the assault "slow and cautious." Given the vastly superior British forces, he believed they should have achieved success sooner.

In His Own Words

"Our attempt to land where we did was rash and injudicious, our success unexpected (by me) and undeserved. There was no prodigious exertion of courage in the affair. Our proceedings were as slow and tedious as the undertaking was ill-advised and desperate."

On August 8 Boscawen and Amherst penned a letter to Pitt stating that an operation against Quebec was now "not practicable" and that "the most that can be done up the River St. Lawrence is to send a fleet of ships and three battalions to destroy the settlements at Miramichi, Gaspe and other places."

Impatient Wolfe resented the fact that instead of leading his men against Quebec, he was force to spend his time "gathering strawberries and other wild fruits of the country with seeming indifference about what is going one in other parts of the world."In London after lengthy deliberation at the highest levels the death-warrant of the French fortress was signed. Pitt and George II decided that "the Fortress and all fortifications of the Town of Louisbourg, together with all the works and Defences of the Harbour to be effectually and entirely demolished and razed and all the materials thoroughly destroyed." Louisbourg was to be levelled because Britain had its naval base at Halifax and it was feared should France regain its strength it would strive to recapture Louisbourg because it meant so much to her trade and her sea power.

Hundreds of skilled sappers and miners were dispatched to Louisbourg in the summer of 1760. Infantrymen aided them and work went forward every day except Sunday and the King's birthday. Miners, sailors and sappers laboured for months using thousands of kilograms of blasting powder to systematically demolish the bastion. Barrel after barrel of powder was placed in 45 chambers dug below the walls and fuses laid. At sunrise on the appointed day, charges were detonated. A succession of roaring explosions smote the sky, surpassing the bombarments of the siege in din and destructive effect. The last mine was blasted on October 17th tumbling the great fortress in utter ruins, its walls overthrown, its moat filled with debris.

By the end of October, 1760 the great citadel, the pride of Louisbourg, had been laid low, converted into a pile of rubble beneath which were buried France's colonial aspirations. Only a few stones and ruined casemates remained as a monument to the great fortress whose fall carried with it the pillars of French power in North America. Men in their hundreds toiled for months with lever, spade and gun powder to destroy it, but the remains of its vast defences told their tale of human valour and human hardship for years after. The officer in charge of the demolition, was a Royal Navy Captain named John Byron, a name made famous by his grandson, George Gordon, who became the celebrated English poet, Lord Byron.

The fortress that would never fall fell. Sic transit gloria Ludovicoburgi. Some bemoaned its vanished glory but the fidgety finger of history "having writ, moved on."

|

Within three weeks of the French surrender of Louisbourg, dispatches with details of the successful assault had reached England. The British victory was received with frenzied rejoicing. Defeats, disasters and exasperating fiascos had been the norm since the war began, but now at last there was a real victory won by the army and navy together and won over the greatest of all rivals - France. "Let joy be unconfined."The country erupted in joyous celebrations. The streets echoed with triumph and blazed with illuminatiions. Loyal addresses poured in from every quarter.

|

King George stood on the palace steps to receive the eleven captured colours and then attended by the whole court celebrated thanksgiving service at St. Paul's Cathedral.

|

William Pitt's wife, Lady Hester, was overjoyed by an event that was

In Her Own Words

"so happy and glorious for my loved England and happy and glorious for my most beloved and admired Husband."

The victory was commemorated with distinctive medals and Parliament passed a special vote of thanks to the senior officers, whose modest reply was simple and sincere. "We are happy to have done our duty."

|

|

|

|

As second in command Wolfe did not share in these honours, but the hero's name was on every lip. His conspicuous leadership led to a punning toast that circulated around Louisbourg. "Here's to the heart of a Wolfe."

|

In Halifax bells pealed, bonfires blazed and cannons boomed from ship and shore. At a grand, state ball in the colony's newly opened Government House, Wolfe, who everyone said was destined for great things, joined in the revelry, singing, drinking and dancing the night away with laughter and lovely ladies. "No sleep till morn when youth and pleasure meet, To chase the glowing hours with flying feet."

|

The summer of 1958 saw the celebration of the two hundredth anniversary of the seond siege of Louisbourg. The Bicentenary Committee wore period costumes of France, Britain and the colonies. Natives appeared with wigwams and birthbark canoes. Divers recovered from the bottom of the harbour a cannon of the French 74-gun ship of the line, Le Prudent, burned during the British night raid.

|

|

Le Prudent - The British set fire to Le Prudent |

A troop landing was made in Kensington Cove where Wolfe's men had won their beachhead. ,/p>

In 1961, Prime Minister John Diefenbaker authorized the rebuilding of Fortress Louisbourg and over the next two decades, workers transformed the weeds, rubble and stone ruins into the impressive historical and interpretive site it is today. Fortunately, the documentation required for this, the largest restoration project ever carried out in Canada, was available on the three-quarters of a million pages, that spelled out everthing about the fort and its contents in the minutest detail. Now the old capital of Isle Royale is back!

|

|

Louisbourg Restored |

Copyright © 2013 Website Administrator