foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

INSUBORDINATE SUBORDINATES

History deceives with whispering ambition.

|

|

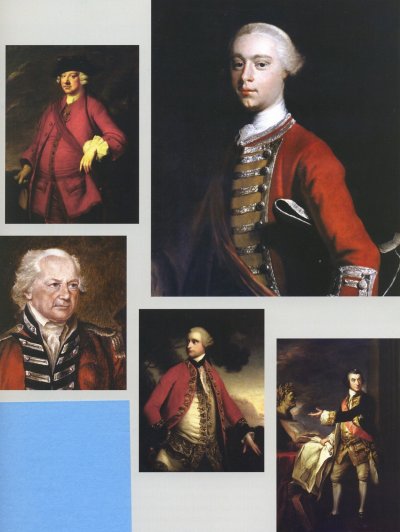

The Cast of Characters |

When Major-General James Wolfe was appointed to his command "up the river," he asked to name his own brigadiers. Lord Ligonier hesitated and Wolfe indicated that unless he had "the assistance of such officers as I should name, His Lordship would do me a great kindness to appoint some other person to the chief direction." This polite but brazen ultimatum undoubtedly came as a shock to Ligonier, but fearing Wolfe would protest directly to Pitt he compromised and allowed Wolfe to choose two of the three brigadiers. Wolfe selected Robert Monckton, James Murray and Ralph Burton, the latter a special friend. Ligonier approved the first two but selected the third himself. He chose the eldest son of a viscount, the Honourable George Townshend, a difficult individual whose appointment contained the seeds of discord to come.

|

|

Monkton-Murray-Townshend |

The three aristocratic brigadiers were all older than Wolfe. They were competent but also ambitious, arrogant and obstinate. All superior to Wolfe by birth and breeding, they resented serving under a general from a lower class. Townshend believed he was as good if not a better officer than Wolfe. Their touchy personalities combined with Wolfe's irritable, ill-natured moods aggravated by his persistent infirmities caused tense, stressful relationships. Their caustic interaction was wearing on Wolfe and the irritation and frustration left a lasting impression of him and them that was less than laudatory.

While Monckton and Murray were appointed to the expedition on Wolfe's own insistence his prickly relationships with them were not conducive of a fine chain of command. Monckton had a soft, kind face, a double chin and heavy-lidded eyes. Wolfe felt confident that he would do as he was told. Wolfe's aide - whose views were doubtless coloured by Wolfe's own opinions - had some harsh things to write about the two officers. He described Monckton as being "of a dull capacity and may properly be called Fat-Headed - timid and utterly unqualified. A month of his command would be sufficient to ruin that excellent army." Monckton, who was senior among the brigadiers, was an impulsive, rash, fearless individual who when he later became governor of New York refused to fight the Americans during the Revolution.

|

|

Brigadier the Hon. Robert Monkton |

James Murray was hard-working, ambitious, astute and eager to achieve fame and glory. He had a little face with large eyes and an angular brow, a long sharp nose and Punch-like chin. Buthe was a capable officer and Wolfe knew he would carry out his orders to the letter. Wolfe's aide's opinion of James Murray was even worse. He condemned him as "the deadly nightshade - the poison of a camp. Envy and Ambition are the only springs that work him. The more brilliant and excellent any character is the more his Envy is excited and the more he detracts.... Mr Wolfe was the means of his being Brigadier General in return he was the very bellows of Sedition and Discord and would have been the first Partisan to arraign Mr Wolfe's conduct had the campaign miscarried in hopes to succeed the command." Murray was a good hater and rarely missed an opportunity to ridicule his leader. He was baffled by Wolfe's popularity with the British people and his intense dislike of Wolfe lasted long after the death of the great general. Fifteen years later he was still trying to belittle Wolfe and

In His Own Words

"knocking my obstinate Scotch head against the admiration and reverence of the English mob for Wolfe's memory."

|

|

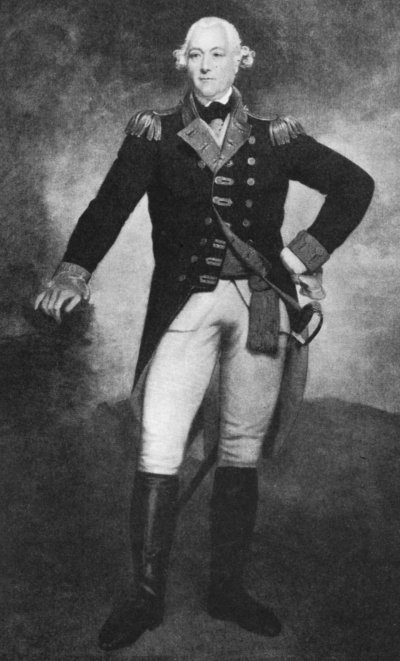

Brigadier the Hon.James Murray |

James Murray, the fifth son of Lord Elibank and the junior brigadier, was a hot-headed, impetuous individual who had wider military experience than any senior officer. He even served in the ranks to the disgust of his family. He had served earlier with Wolfe with whom he had quarrelled violently. Wolfe spoke of him as "my old antagonist," but he had fought so well at Louisbourg that Wolfe forgave him. Murray never forgave Wolfe, alive or dead; he was too stubborn for that. He was a man of passionate and fearless courage of whom a close colleague gave this character description. "He is fiery, proud of his strength, decided in his ideas and eager to distinguish himself. He is to be feared when opposed and becomes easily inflamed. Too great an opinion of one's strength often leaves little opportunity for reflection and consideration and frequently gives reason for subsequent regret." Still he could be relied upon to do his duty, while at the same time claiming more that his fair share of credit.

After the surrender of Quebec, Murray was left in command. In April 1760 the Chevalier de Levis, who was Montcalm's second in command, pulled together 7000 troops to retake Quebec. On the 27th of April he assembled 3800 troops on a battlefield at St. Foy. Murray failed to learn from Montcalm for he marched 3866 troops out to meet Levis on the field of battle. This time the British were routed and pursued to the gates of Quebec. Reinforcements from France never came, however, and when further resistance was deemed futile, Levis ordered his regiments to burn their colours to avoid dishonour. What remained of the French and Canadian regulars stacked their arms. Canada had finally been conquered.

Murray became the second English governor of Canada and in this position he did everything in his power to ease the suffering of the people of New France at the end of a devastating war. He became very popular with French Canadians, but was hated by the English merchants, whom Murray described as "inferior representatives of their nation." Nevertheless their constant complaints regarding his actions resulted in Murray's recall to England and although he was cleared of all accusations he declined to return to Canada.

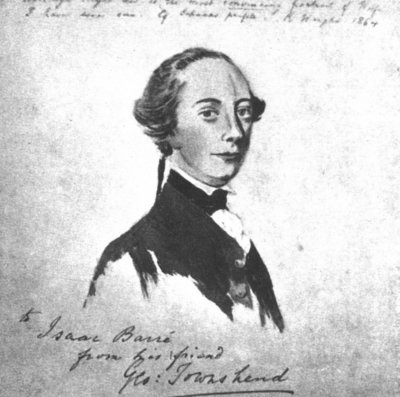

Finally there was George Townshend. He was heir to three centuries of courtly splendor and military glory. He saw no necessity to prove himself in battle, improve himself by studying books or by taking dancing lessons. Vain, arrogant, satirical and self-seeking, he stood in awe of no man and would do his duty as the Townshends always had. He was ready to go to war, but on his own terms. Superior to Wolfe in both birth and years, Townshend was proud, clever, aloof, quarrelsome, pompous and maliciously witty. His portrait portrays his character. His heavy-lidded, languid, contemptuous, mocking eyes gave the impression of a person both worldly and self-indulgent. His appointment had not been of Wolfe's own choosing. Wolfe disliked and distrusted him from the beginning, but was in no position to raise objections. His letter of welcome was suitably ingratiating, but it did contain a barbed reference to Townshend's lack of experience which the brigadier greatly resented.

Townshend was not a professional soldier and his only discernable qualifications for the position were his political connections and his powerful, influential friends. Wolfe's aide-de-camp (ADC) dismissed him as being of "a feeble inconstant mind, his line of life not directed by any first principles and he is exceedingly subject to very high and very low spirits." Townshend had, the young officer wrote, "a great deal of humour, well stain'd with bawdy." The best he could find to say of him was that he "may be esteemed an excellent Tavern acquaintance."

|

|

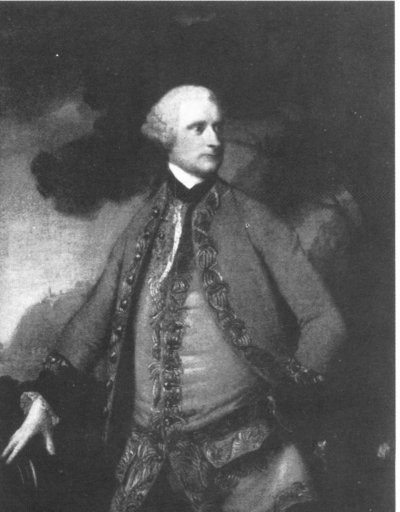

Brigadier the Hon.George Townshend |

|

|

George Marquis Townshend (Because of Wolfe's death and Monckton's serious wound, Townshend assumed chief command and the town surrendered to him.) |

|

|

Townshend |

Townshend was three years older than James. He was bitter at what he considered to have been unjust treatment in the past and extremely sensitive. Doubtless, Wolfe did not treat him with sufficient tact and this provoked trouble - especially since he was vain enough to consider himself to be the better general. He confided his resentment to his journal. "When I had built some elaborate breastworks overlooking the Montmorency, for example, the next morning, the General having gone early to rest in the evening, I reported to him what I had done and in the evening he went round and disapproved of it, saying I had indeed made myself secure for I had made a fortress; that small redoubts were better than lines; that the men could not man these lines, nor sally out as they pleased.... The next day I perceived with my glass an officer with an escort very much answering the description of M. Montcalm examining our camp from the same spot. I acquainted the General with this, who rather laughed at it and at my expectation of any annoyance from that part.... Whilst I was directing the work, I heard the General had set out for the Point of Orleans, thence to pass over to the Point of Levis leaving me, the first officer in the camp, not only without orders but also even ignorant of his departure or time of return."

Disagreements between these two men may have occurred with some regularity. One of these occasions was referred by Wolfe in his diary when he recorded that there was

In His Own Words

"some difference of opinion upon a point termed slight & insignificant & the Commander in Chief is threatened with Parliamentary Inquiry into his Conduct for not consulting an inferior Officer & seeming to disregard his Sentiments." The reason for this is not known but Townshend is the only brigadier who would have felt he could threaten Parliamentary action.

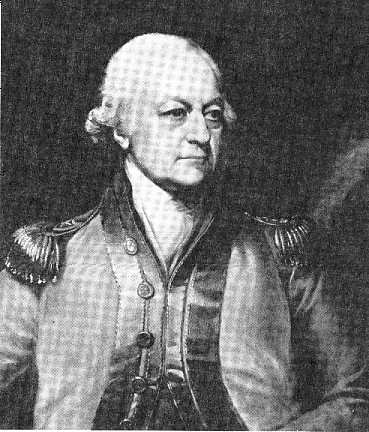

Townshend, who was second in seniority, was an arrogant heir to a viscountcy who became a marquis and a field marshal. When Wolfe was killed it was Townshend who succeeded to command and because Monckton had been seriously wounded, Townshend accepted the capitulation of Quebec. Shortly thereafter Townshend returned to England. Some suggested his unseemly haste was an unsuccessful attempt to reap glory from the glittering victory.

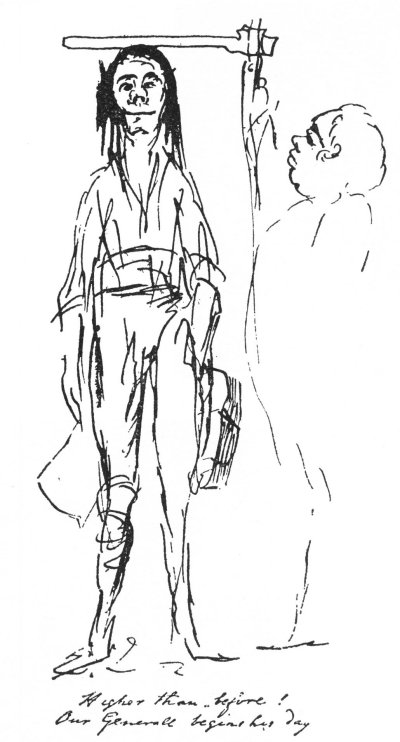

Townshend was a talented artist and a caricaturist and delighted in mocking and viciously exaggerating the physical flaws of those around him. Caricature, a cruel art, delighted the haughty, mocking aristocrat who spent much of his time drawing caricatures of his superiors and others. Wolfe was one of his favourite subjects and both before and after the campaign on the Plains of Abraham, Townshend belittled Wolfe whom he labelled "a fiery-headed fellow fit only for fighting." In a letter to his wife, Townshend wrote, "General Wolfe's health has been very bad and in my opinion his Generalship is not a bit better."

|

|

Caricature by Townshend showing Wolfe's friend and adjutant measuring the general: "Higher than before! Our general begins his day." |

|

|

Another of Townshend's caricatures of Wolfe |

|

|

Two Caricatures of Wolfe by Townshend Drawn Before Quebec, 1759 |

|

|

A War Captain Ready For War & Carrying A Scalp [by George Townshend] |

Townshend used any opportunity to ridicule his commander. When Wolfe wrote a masterly account of the British siege of Quebec, Townshend said it was so good it could not have been written by Wolfe, but must have been written by his brother, George Townshend, who was one of Wolfe's aides-de-camp. Later when George Townshend's own official account was published it was found to be much less impressive than Wolfe's. A fellow officer stalked up to Townshend and asked, "Look here Charles, if your brother wrote Wolfe's account, who on earth wrote your brother's?"

Townshend saw everything in a farcical light, most especially his pale and gangling general, a splendid subject for his pen. Wolfe was aware of Townshends' critical caricatures and suffered them in silence, but the barbs bothered him greatly. Wolfe's dislike of Townshend was greatly increased when Wolfe happened to see one of Townshend's insulting cartoons in the officers' mess. Asked to entertain his fellow officers with his famous caricatures, Townshend drew a derisive picture of Wolfe, an amusing but insulting cartoon that lampooned Wolfe's leadership before the big battle. He caricatured Wolfe's scrawny figure and sharply pointed profile. When it was passed around, it caused roars of laughter. One officer thought Wolfe might share the humour and showed it to him. Wolfe was not amused; his face turned a deathly pale and as he crumpled the paper and put it into his pocket, he said, looking directly at Townshend with a bleak smile,

In His Own Words

"If we live, this shall be inquired into."

Townshend's drawings, while clever and comical, were also spitefully disrespectful and insubordinate to his commander-in-chief. Wolfe said, "I neither ask for nor expect any form of favour, but I have no intention of submitting to any ill-usage whatsoever."

The talented Townshend could also produce more serious works. He is said to have drawn a very convincing and one of the better portraits of Wolfe, a head-and-shoulder study painted in water colours by the normally biting brigadier. The gentle humour about the mouth and the observant and worried eyes suggest a sympathy, perhaps even affection, with his subject. While Townshend shared Murray's hostility towards Wolf, time softened Townshend's sentiments and in later years he persuaded Murray to forget about attacking the memory of the dauntless hero.

|

|

Major General James Wolfe (from a water-colour by George Townshend made during the Quebec campaign in 1759 |

Wolfe's relationship with Monckton is not as well known. Wolfe's frustration at Monckton's failure to find a French weakness prompted Wolfe to order harsh measures against the vulnerable Canadian settlements. Monckton, who disagreed with Wolfe's severe orders, delayed implementing some of the more violent ones. When he did finally execute Wolfe's instructions, he lessened the severity of the more brutal commands. For a time tensions were strained between the two men, but later Wolfe commended Monckton's "infinite spirit" and "great services." In a codicil added to his will which he had made in June, 1759, Wolfe left his clothes and weapons to Monckton. Wolfe left his silver to Admiral Saunders and his books and papers to Sir Guy Carleton.

Jealousy motivated much of the ill-feeling the brigadiers felt towards Wolfe. Extraordinary acclaim and glory were bestowed upon their illustrious commander and they believed him unworthy of it. They thought they should have shared the same fame. Their disdain towards Wolfe was undoubtedly caused too by their resentment of Wolfe's aloof manner and his refusal to take them into his confidence. "Every step he takes is wholly his own; he asks no one's opinion and wants no advice." Wolfe's opinion of the brigadiers' loyalty was demonstrated by the fact that he did not tell them until the night of the assault the actual spot he had chosen. From that hour until his death at 10:35 the next morning, the authorship and the execution of the plan and the battle were Wolfe's alone. The brigadiers' resentment undoubtedly stemmed from frustration at their believing the door to their ambitions seemed bolted and barred by Wolfe's secretiveness.

The brigadiers were also exasperated by Wolfe's indecisiveness. "Within five hours we received at the general's request, three different orders which were then contradicted immediately that we received them to the amazement of all concerned." Perhaps this was part of Wolfe's strategy of keeping the enemy guessing. Whatever the reason, the brigadiers, finally in frustration requested in a letter that he give them "distinct orders about the place or places we are to attack."

Monckton was the least embittered of Wolfe's brigadiers and the only one who agreed to being included in Benjamin's West's famous, but factually faulty painting, The Death of Wolfe. [*] Monckton recovered from a chest wound and returned to England as a lieutenant general where he was appointed Governor of Portsmouth which he represented in Parliament. He never married and died in 1782 aged fifty-six.

Townshend inherited his family's great estates and became master at Raynham, fourth viscount and later Marquess Townshend. He was Lord Lieutenant of Ireland for five years. In 1773 he fought a duel and killed his opponent. He was later proclaimed a full general and then a field marshal. He was contacted by Murray who said he intended to publish his theory that Wolfe never intended to fight a general action. Murray said he unable to understand why the "English mob had so much admiration and reverence for Mr. Wolfe's memory." Townshend told him to forget his theory and to forget Quebec as Townshend said he had. Townshend died aged 83 in 1807.

|

|

Townshend in later life. |

In his five years as Governor of Canada, Murray became very fond of Canada and its people whom he called "perhaps the bravest and best race upon the Globe." He treated them so well, in fact, that newly-arrived English merchants complained that he discriminated against his own countrymen. Murray was ordered home to England where he faced a parliamentary inquiry. He was exonerated but never returned to Canada. He became a full general and died in 1794 at the age of seventy-two. He never changed his opinions about Wolfe, the Canadians or anything else.

Thus out of three brigadiers, Wolfe got one who sneered at him and openly despised him and one who hated him quietly and steadily. While they were all sons of peers, they knew that social rank and the quality of blood to be shed were not as important in North America as they would have been on the fashionable battlefields of Europe, where one allowed the enemy the courtesy of firing first. North America was a middle-class place: ideal for the likes of a Wolfe, but below the level of a Townshend.

[*]Wolfe died with only four aides in attendance. Samuel Holland, a surveyor after whom Holland Landing north of Toronto is named, was present during the Battle of the Plains of Abraham. Holland returned to Wolfe's side from a dangerous engineering operation, only to find him dying. Wolfe must have been on friendly terms with Holland for he gave him a pair of dueling pistols. The gift brought only heartbreak to Holland for his 19-year old son was killed later fighting a duel. Holland made the following comment regarding the painting. "In the battle of September 13, I lost my protector (Wolfe) while holding his wounded hand at the time he expired. For reasons best known to Mr. West, the painter, I was not included amongst the group represented. Others exhibited in that painting were never in the battle." Holland's statement conflicts with other information indicating that Moncton was the only brigadier willing to be depicted in West's painting as one of those clustered about Wolfe when "his valiant spirit fled." |

|

Death of Wolfe |

This very popular painting became a symbol of British global growth and power. Although the setting, scenery and attendants were completely symbolic, the painting, which made West a wealthy man, was reproduced or adapted many times. West made six monumental paintings of the famous death scene, the first of which was completed in 1771.

Copyright © 2013 Website Administrator