Foreward | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

BRADDOCK'S DEBACLE

History is like that - very chancy.

The Americans believed their future dominion over all of the North American continent - what Thomas Jefferson termed "an empire of liberty" and others later called "manifest destiny" - required that they break the shackles that bound them to Britain's economic and military will. That decision meant war. Who was to rally the rebels?

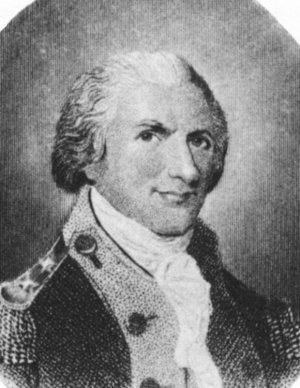

The Seven Years' War provided miltary training for some colonial officers, one of whom was George Washington. Washington served under Major General Edward Braddock when he led a combined force of redcoats and colonial militiamen against the French at Fort Duquesne.

|

|

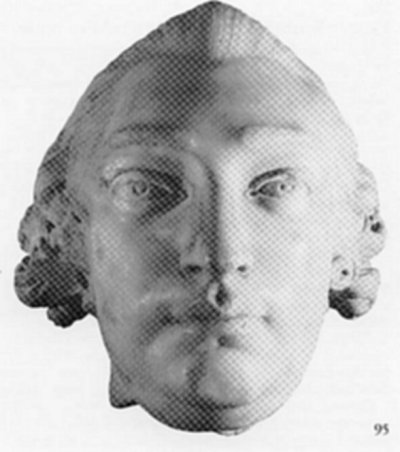

Braddock |

Notwithstanding the pretenses of peace being elaborately maintained in Britain and France, both countries were preparing for war. The French were feverishly building warships and assembling troops for service in Canada, while the British were amassing an army under General Major General Edward Braddock for dispatch to Virginia.

On December 22, 1754 HMS Norwichand Centurian slipped their moorings at Spithead and tacked west to Virginia. Braddock was aboard the Norwich as it ploughed through the waves of the wild and boisterous sea. Braddock's orders were flexible: drive the Canadians and the French regulars from their encroachments in Ohio; take Fort Niagara; seize Crown Point and destroy Fort Beausejour. As commander-in-chief, Braddock commanded a combined force of colonial and regular units, his army comprising the mightiest force ever assembled up to then in America.

Braddock with two battalions totalling 1,000 redcoats arrived in Virginia in February 1755. Although not prepared to pay taxes to the king, nor take proper measures to protect themselves, the colonists wildly welcomed the redcoats and their distinguished officer, whose mere presence, they believed, would frighten off the French and remove that persistent danger. A single volley from the sovereign's soldiers would suffice to send the French back to the confines of Canada.

Braddock, a bull-dog type of general, was a stocky, burly, ruddy-faced, obstinate and fearless model Guards officer. He was "desperate in his fortune, brutal in his behaviour and obstinate in his sentiments, but intrepid and courageous." The general himself had few illusions. Just before he left England, he spoke with an actress friend who recorded his comments. "The general told me he would see me no more. He was going with a handful of men to conquer a whole nation and to do this they must cut their way through unknown woods." Producing a map he told her, "We are sent like sacrifices to the altar." Although stubborn and stolid, Braddock faced the fate he expected undaunted.

Braddock was appalled by Pennsylvania's lack of magazines and storehouses. "The jealousy of the people and the disunion of many colonies are such that I almost despair of succeeding." Ostensibly the colonies were to pay for the troops, but the ministry conceded they would not likely do so. Braddock was told in secret instructions to forward his bills to the paymaster in London. True to form the colonies found a variety of ways to dodge their responsibilities. The bills were sent home. Braddock quickly learned about the realities of politics in America. Normally, he issued orders and saw them obeyed, but he learned that life in the colonies was different. Bickering, prevarication and petty jealousies were the norm and obedience to any order was rare. Money promised never came. Wagons and teams to pull them never appeared. He received a mere tenth of the 2500 horses and two hundred wagons he required. Provisions if they arrived were late and always less than promised.

Washington, who joined Braddock at Frederick, Maryland, was nursing a gripe. As commander in chief, Braddock had the King's authority to grant royal commissions, but only up to the rank of captain. A sycophantic Washington begged for a royal commission. He wanted to be a colonel and refused a captaincy as being beneath his dignity. He resigned in a huff and returned to Mount Vernon. Braddock needed Washington's knowledge of the country to be crossed and he devised a clever way around the question of rank. His aide informed Washington that "General Braddock will be very glad of your company in his family by which all inconveniences of that sort, that is, rank restrictions, will be obviated." Braddock's solution: to give Washington a place, albeit unofficial, on his staff as colonel. A molified Washington returned to Frederick to join his new 'family.'

|

|

George Washington |

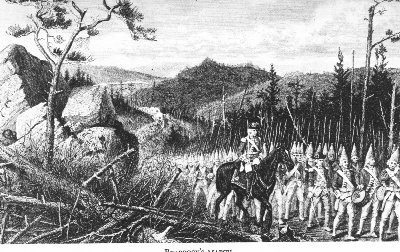

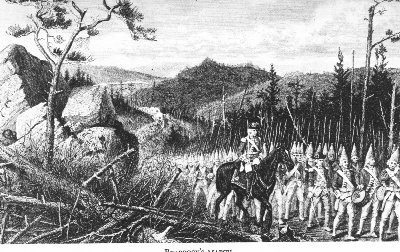

After supplementing his forces with the best of the blue-coated Virginians, Braddock prepared to depart with 1500 regulars, provincials and a powerful artillery train for Fort Duquesne at the forks of the Ohio. Drums rolled and bugles blared as the expedition assembled in spit and polish parade ground formation. Discipline was everything to Braddock who never saw any further than the tactics he'd been taught: discipline, fire power, simultaneous volleys and unquestioning abedience to the bellowed orders of an officer. With cannons, cattle and wagons hurriedly commandeered by Benjamin Franklin, the axemen prepared to hack their way through the Alleghenies and the Monongahela. The impressive force lacked little but leadership The foe they faced were Native warriors and regulars, infantry units raised for guard duty in the naval ports of France and for service in the colonies. The officer corps were Canadians. All other ranks were occupied by the regulars came from France. They were trained in drill manoeuvres of the European style warfare, but were also great guerilla fighters who could travel long distances, live off the land and strike swiftly and vanish before their victims could counterattack. Great mobility, deadly marksmanship, skillful use of surprise and forest cover and a high morale stemming from a tradition of victory gave them the superiority they were about to display. Braddock had been cautioned by Benjamin Franklin that fighting in the forests of America was not like fighting on the battlefields of Europe and urged him to avoid "ambuscades." Braddock was contemptuous of forest guerilla fighters and bristled at this advice. He responded disdainfully, "They may indeed be a formidable enemy to the raw, American militia, but upon the king's regular and disciplined troops it is impossible that they will make any impression." He believed the ponderous, massed military movements of trained troops would overcome all obstacles and scoffed when told he'd be lucky to see the enemy. Washington concerned by Braddock's brusque dismissal of this sage advice and wondered at a leader who refused to listen to those who knew the forest and the fighters it could conceal. Washington had joined the expedition to acquire military doctrine at the fountainhead, but his leader was clueless of the sort of battle they were about to fight and hautily derisive of the wise warning he was given. Braddock was so certain of his victories, said one Canadian writer contemptuously, that he expected "to have breakfast at La Belle Riviere, dinner at Niagara and supper at Montreal." Braddock's March

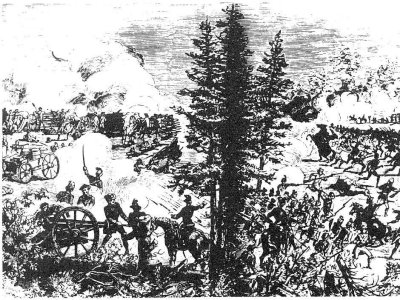

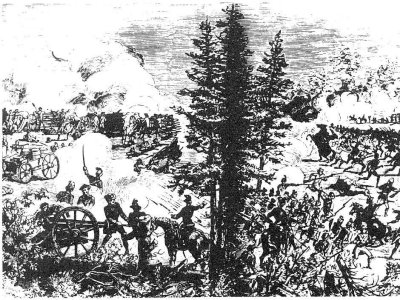

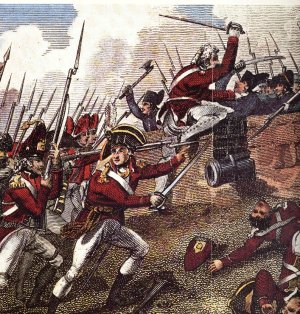

Braddock's men made a flashy show of brilliant scarlet and bright steel as they marched towards Duquesne in two-file formation in order to impress the French with a sense of their irresistable strength. The movement of the fine force through the wild, primevil forest was agonizingly slow. In the lead were companies of axemen cutting out a 12-foot wide road along which the four-mile long columns snaked. The wonder is they moved at all for the roadway had to be hacked through forests and blasted across rock ledges. Corduroyed roads were constructed through swamps and bridges were built over streams to accommodate a herd of cattle and straining horses hauling creaking supply wagons and large, lurching gunwagons containing 8-inch howitzers (each required a team of seven horses), four 12-pounders (each required a team of five horses), fifteen mortars and six 6-pounders over the makeshift mountain trail. On June 8th Braddock wrote, "I have a hundred and ten Miles to march thro' an uninhabited wilderness over steep, rocky Mountains and almost impassable Morasses." The trek was an extraordinary military feat and despite its tragic ending, Braddock's march to Fort Duquesne was a monumental achievement in military logistics. The French knew of Braddock's approach and were fearful that a force of its size would overwhelm the defences of the fort. The only possibility for a successful resistance lay in marching to meet and engage the enemy in the forest before they reached the Ohio River. Augmenting the small French force were some 800 Natives from various tribes who had sought refuge from the Europeans in this very region about to become their battlefield. One of the warriors, a Delaware, commented that Braddock's army was advancing in very close order and that the Indians would soon surround them, "take to the trees and shoot um all down like pigeons." On the morning of the 9th the French and their Aboriginal allies drew powder and shot and marched off to pick off the 'pigeons.' The British saw no scouts. In fact, they rarely saw the sky and the only fighting was with the forces of nature until the little army crossed the Monongahela River 10 miles from the French fort. On July 8, 1755 the sylvan silence was broken by blood-curdling screams and for the first time ever, British soldiers heard the paralyzing war hoops of the Iroquois warriors. A young lieutenant made notes of the nightmare. "I cannot describe the horrors of the scene; no pen could do it. The yell of the Indians is fresh in my ears, the terrible sound will haunt me till the hour of my death." From the flanks Native and French fighters bushwhacked the bewildered redcoats, whose scarlet uniforms bedazzled but did blend in with the surrounding country. The soldiers made tantalizing targets as they sought frantically to find shelter from the unseen snipers. Since there was no visible foe to fire at the British shot ineffectually at puffs of smoke and the phantom fighters were invulnerable to their fusillades. Some Virginians took cover behind trees and logs fighting as their foes fought. Maddened at this manoeuvre which offended his conception of courage, Braddock cursed, threatened and ordered them back into line. Bellowing with sword in hand, he rode up and down the ranks beating with the flat of his weapon any of the stunned and bewildered men who attempted to take cover from the carnage. As British soldiers fell fast and their officers fell faster, discipline collapsed and the ranks were reduced to a milling mass of frightened, frantically bewildered men. The British army became a complete and utter shambles. Ceasing to advance the beleaguered force became an enormous target whose soldiers fired off their twenty-four rounds of ammunition "in the most confused manner, some in the air, some in the ground." The few surviving officers lost complete control of their men and were unable to organize an effective counterattack. As the slaughter became more than flesh and blood could stand, the ranks quivered, wavered and broke, melting into a shapeless scarlet mass. Retreat turned to rout as most of the survivors fled in a blind panic. The few who remained fought with fierce tenacity, but "had only death" before them. They knew the terror of the tomahawk. Walked right into a French and Indian ambush.

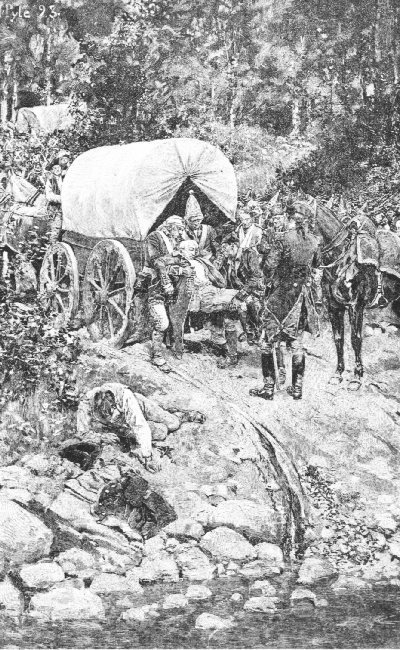

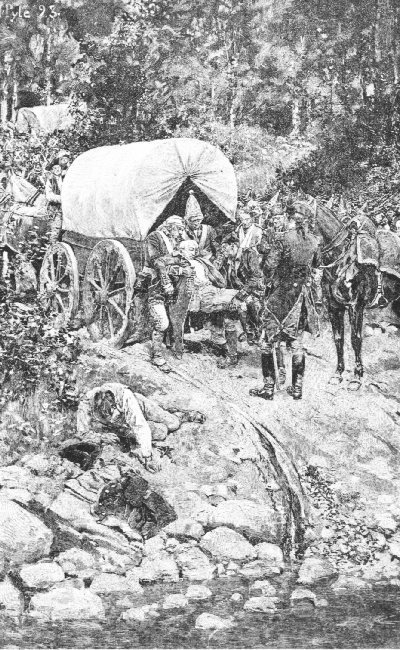

Bradddock, who was in the heat of the action the whole time, exposed himself at every poin. He had four horses killed under him as for nearly an hour and a half he rode amid the disintegrating ranks. By mid-afternoon with nearly three-quarters of his troops wounded or dead, he gave the order to withdraw. As drums sounded the signal, the men lost little time in retreating down the road. No sooner had Braddock mounted the fifth horse, than he was shot through the right arm, the missle passing into his lungs. The wound was mortal. As he was carried to the rear, he kept moaning, "Who would have thought it?" He died later muttering, "We shall know better know how to deal with them another time." The victory and the defeat were decisive. The three hours of mass murder took a terrible toll on the redcoats. Loss of British life was immense. Four hundred and fifty-six killed and 520 wounded out of a force of 1469. French-Aboriginal losses totalled 22 killed and 16 wounded out of 891. The British frontier remained at the Alleghanies and the French continued to occupy the whole of the Ohio Valley. The Death of General Braddock

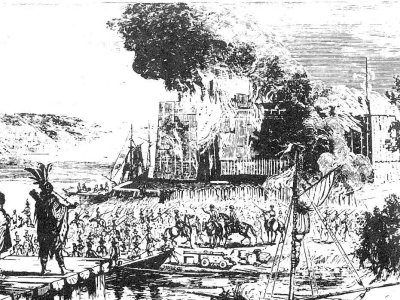

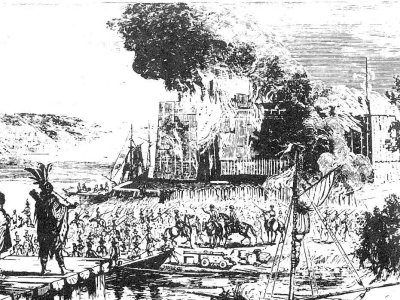

It was a terrible trouncing. British commanders had much to learn about fighting in North America. It was their first and most difficult lesson. They found it hard to change and harder still to accept advice from mere militiamen. Washington, the only member of Braddock's staff not killed or wounded, rode all night to bring word of the disaster back to that part of Braddock's force waiting with the wagons some distance from the fiasco. Washington, who survived the hail of bullets in Braddock's debacle, vowed to be better prepared in a similar situation next time. It never dawned on him that the next time the foe he'd be firing at would be the British. When he did face them across the battlefield, he remembered the rout of the redcoats that shattered the myth of their invincibility. Three years later following the French defeat at Louisbourg, the redcoats and colonials including Washington launched another assault on Fort Duquesne. A different route resulted in another tough march along a hacked-out road through woods, over swamps and up precipitous hills. On November 5 after an exhausting trek in mud and torrential rain, a council of war was called. It was decided that the expedition should proceed no further that year. Shortly thereafter an unbelievable report was received that the French and their Native allies were abandoning Fort Duquesne. The French could no longer mainain this advanced position because the British had captured Fort Frontenac. The British force decided to attack the weakened garrison and on November 24 as they approached the bastion, a great explosion rent the sky. The French had destroyed Fort Duquesne. Fort Duquesne - Its evacuation and destruction.

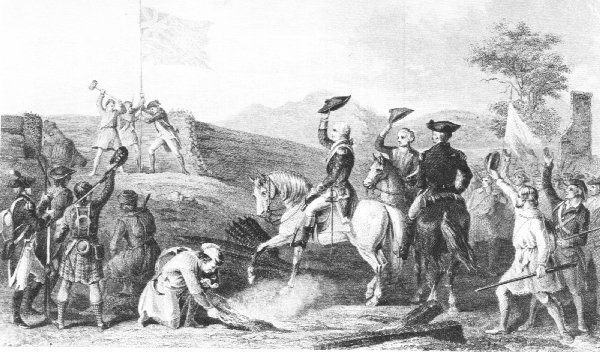

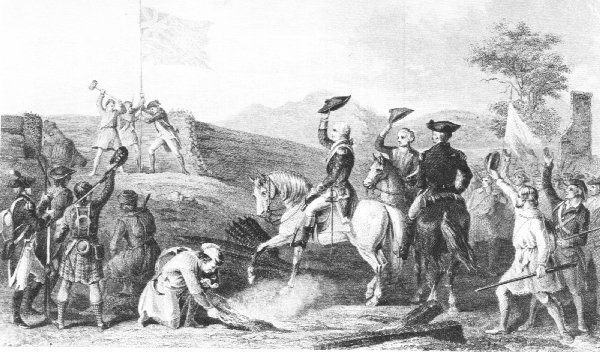

A day later the British reached the ruins which they renamed Fort Pitt, the present site of Pittsburg. The middle American colonies sang songs of praise for the French forces that terrorized the frontier had at last been defeated and driven out. Washington was heralded as a hero. A Presbyerian minister's comments at the time were prophetic. George Washington Raising the British Flag at Fort Duquesne (renamed Fort Pitt)

The Americans believed their future dominion over all of the North American continent - what Thomas Jefferson termed "an empire of liberty" and others later called "manifest destiny" - required that they break the shackles that bound them to Britain's economic and military will. That decision meant war. Who was to rally the rebels? The Seven Years' War provided miltary training for some colonial officers, one of whom was George Washington. Washington served under Major General Edward Braddock when he led a combined force of redcoats and colonial militiamen against the French at Fort Duquesne. Braddock

Notwithstanding the pretenses of peace being elaborately maintained in Britain and France, both countries were preparing for war. The French were feverishly building warships and assembling troops for service in Canada, while the British were amassing an army under General Major General Edward Braddock for dispatch to Virginia. On December 22, 1754 HMS Norwichand Centurian slipped their moorings at Spithead and tacked west to Virginia. Braddock was aboard the Norwich as it ploughed through the waves of the wild and boisterous sea. Braddock's orders were flexible: drive the Canadians and the French regulars from their encroachments in Ohio; take Fort Niagara; seize Crown Point and destroy Fort Beausejour. As commander-in-chief, Braddock commanded a combined force of colonial and regular units, his army comprising the mightiest force ever assembled up to then in America. Braddock with two battalions totalling 1,000 redcoats arrived in Virginia in February 1755. Although not prepared to pay taxes to the king, nor take proper measures to protect themselves, the colonists wildly welcomed the redcoats and their distinguished officer, whose mere presence, they believed, would frighten off the French and remove that persistent danger. A single volley from the sovereign's soldiers would suffice to send the French back to the confines of Canada. Braddock, a bull-dog type of general, was a stocky, burly, ruddy-faced, obstinate and fearless model Guards officer. He was "desperate in his fortune, brutal in his behaviour and obstinate in his sentiments, but intrepid and courageous." The general himself had few illusions. Just before he left England, he spoke with an actress friend who recorded his comments. "The general told me he would see me no more. He was going with a handful of men to conquer a whole nation and to do this they must cut their way through unknown woods." Producing a map he told her, "We are sent like sacrifices to the altar." Although stubborn and stolid, Braddock faced the fate he expected undaunted. Braddock was appalled by Pennsylvania's lack of magazines and storehouses. "The jealousy of the people and the disunion of many colonies are such that I almost despair of succeeding." Ostensibly the colonies were to pay for the troops, but the ministry conceded they would not likely do so. Braddock was told in secret instructions to forward his bills to the paymaster in London. True to form the colonies found a variety of ways to dodge their responsibilities. The bills were sent home. Braddock quickly learned about the realities of politics in America. Normally, he issued orders and saw them obeyed, but he learned that life in the colonies was different. Bickering, prevarication and petty jealousies were the norm and obedience to any order was rare. Money promised never came. Wagons and teams to pull them never appeared. He received a mere tenth of the 2500 horses and two hundred wagons he required. Provisions if they arrived were late and always less than promised. Washington, who joined Braddock at Frederick, Maryland, was nursing a gripe. As commander in chief, Braddock had the King's authority to grant royal commissions, but only up to the rank of captain. A sycophantic Washington begged for a royal commission. He wanted to be a colonel and refused a captaincy as being beneath his dignity. He resigned in a huff and returned to Mount Vernon. Braddock needed Washington's knowledge of the country to be crossed and he devised a clever way around the question of rank. His aide informed Washington that "General Braddock will be very glad of your company in his family by which all inconveniences of that sort, that is, rank restrictions, will be obviated." Braddock's solution: to give Washington a place, albeit unofficial, on his staff as colonel. A molified Washington returned to Frederick to join his new 'family.' George Washington

After supplementing his forces with the best of the blue-coated Virginians, Braddock prepared to depart with 1500 regulars, provincials and a powerful artillery train for Fort Duquesne at the forks of the Ohio. Drums rolled and bugles blared as the expedition assembled in spit and polish parade ground formation. Discipline was everything to Braddock who never saw any further than the tactics he'd been taught: discipline, fire power, simultaneous volleys and unquestioning abedience to the bellowed orders of an officer. With cannons, cattle and wagons hurriedly commandeered by Benjamin Franklin, the axemen prepared to hack their way through the Alleghenies and the Monongahela. The impressive force lacked little but leadership The foe they faced were Native warriors and regulars, infantry units raised for guard duty in the naval ports of France and for service in the colonies. The officer corps were Canadians. All other ranks were occupied by the regulars came from France. They were trained in drill manoeuvres of the European style warfare, but were also great guerilla fighters who could travel long distances, live off the land and strike swiftly and vanish before their victims could counterattack. Great mobility, deadly marksmanship, skillful use of surprise and forest cover and a high morale stemming from a tradition of victory gave them the superiority they were about to display. Braddock had been cautioned by Benjamin Franklin that fighting in the forests of America was not like fighting on the battlefields of Europe and urged him to avoid "ambuscades." Braddock was contemptuous of forest guerilla fighters and bristled at this advice. He responded disdainfully, "They may indeed be a formidable enemy to the raw, American militia, but upon the king's regular and disciplined troops it is impossible that they will make any impression." He believed the ponderous, massed military movements of trained troops would overcome all obstacles and scoffed when told he'd be lucky to see the enemy. Washington concerned by Braddock's brusque dismissal of this sage advice and wondered at a leader who refused to listen to those who knew the forest and the fighters it could conceal. Washington had joined the expedition to acquire military doctrine at the fountainhead, but his leader was clueless of the sort of battle they were about to fight and hautily derisive of the wise warning he was given. Braddock was so certain of his victories, said one Canadian writer contemptuously, that he expected "to have breakfast at La Belle Riviere, dinner at Niagara and supper at Montreal." Braddock's March

Braddock's men made a flashy show of brilliant scarlet and bright steel as they marched towards Duquesne in two-file formation in order to impress the French with a sense of their irresistable strength. The movement of the fine force through the wild, primevil forest was agonizingly slow. In the lead were companies of axemen cutting out a 12-foot wide road along which the four-mile long columns snaked. The wonder is they moved at all for the roadway had to be hacked through forests and blasted across rock ledges. Corduroyed roads were constructed through swamps and bridges were built over streams to accommodate a herd of cattle and straining horses hauling creaking supply wagons and large, lurching gunwagons containing 8-inch howitzers (each required a team of seven horses), four 12-pounders (each required a team of five horses), fifteen mortars and six 6-pounders over the makeshift mountain trail. On June 8th Braddock wrote, "I have a hundred and ten Miles to march thro' an uninhabited wilderness over steep, rocky Mountains and almost impassable Morasses." The trek was an extraordinary military feat and despite its tragic ending, Braddock's march to Fort Duquesne was a monumental achievement in military logistics. The French knew of Braddock's approach and were fearful that a force of its size would overwhelm the defences of the fort. The only possibility for a successful resistance lay in marching to meet and engage the enemy in the forest before they reached the Ohio River. Augmenting the small French force were some 800 Natives from various tribes who had sought refuge from the Europeans in this very region about to become their battlefield. One of the warriors, a Delaware, commented that Braddock's army was advancing in very close order and that the Indians would soon surround them, "take to the trees and shoot um all down like pigeons." On the morning of the 9th the French and their Aboriginal allies drew powder and shot and marched off to pick off the 'pigeons.' The British saw no scouts. In fact, they rarely saw the sky and the only fighting was with the forces of nature until the little army crossed the Monongahela River 10 miles from the French fort. On July 8, 1755 the sylvan silence was broken by blood-curdling screams and for the first time ever, British soldiers heard the paralyzing war hoops of the Iroquois warriors. A young lieutenant made notes of the nightmare. "I cannot describe the horrors of the scene; no pen could do it. The yell of the Indians is fresh in my ears, the terrible sound will haunt me till the hour of my death." From the flanks Native and French fighters bushwhacked the bewildered redcoats, whose scarlet uniforms bedazzled but did blend in with the surrounding country. The soldiers made tantalizing targets as they sought frantically to find shelter from the unseen snipers. Since there was no visible foe to fire at the British shot ineffectually at puffs of smoke and the phantom fighters were invulnerable to their fusillades. Some Virginians took cover behind trees and logs fighting as their foes fought. Maddened at this manoeuvre which offended his conception of courage, Braddock cursed, threatened and ordered them back into line. Bellowing with sword in hand, he rode up and down the ranks beating with the flat of his weapon any of the stunned and bewildered men who attempted to take cover from the carnage. As British soldiers fell fast and their officers fell faster, discipline collapsed and the ranks were reduced to a milling mass of frightened, frantically bewildered men. The British army became a complete and utter shambles. Ceasing to advance the beleaguered force became an enormous target whose soldiers fired off their twenty-four rounds of ammunition "in the most confused manner, some in the air, some in the ground." The few surviving officers lost complete control of their men and were unable to organize an effective counterattack. As the slaughter became more than flesh and blood could stand, the ranks quivered, wavered and broke, melting into a shapeless scarlet mass. Retreat turned to rout as most of the survivors fled in a blind panic. The few who remained fought with fierce tenacity, but "had only death" before them. They knew the terror of the tomahawk. Walked right into a French and Indian ambush.

Bradddock, who was in the heat of the action the whole time, exposed himself at every poin. He had four horses killed under him as for nearly an hour and a half he rode amid the disintegrating ranks. By mid-afternoon with nearly three-quarters of his troops wounded or dead, he gave the order to withdraw. As drums sounded the signal, the men lost little time in retreating down the road. No sooner had Braddock mounted the fifth horse, than he was shot through the right arm, the missle passing into his lungs. The wound was mortal. As he was carried to the rear, he kept moaning, "Who would have thought it?" He died later muttering, "We shall know better know how to deal with them another time." The victory and the defeat were decisive. The three hours of mass murder took a terrible toll on the redcoats. Loss of British life was immense. Four hundred and fifty-six killed and 520 wounded out of a force of 1469. French-Aboriginal losses totalled 22 killed and 16 wounded out of 891. The British frontier remained at the Alleghanies and the French continued to occupy the whole of the Ohio Valley. The Death of General Braddock

It was a terrible trouncing. British commanders had much to learn about fighting in North America. It was their first and most difficult lesson. They found it hard to change and harder still to accept advice from mere militiamen. Washington, the only member of Braddock's staff not killed or wounded, rode all night to bring word of the disaster back to that part of Braddock's force waiting with the wagons some distance from the fiasco. Washington, who survived the hail of bullets in Braddock's debacle, vowed to be better prepared in a similar situation next time. It never dawned on him that the next time the foe he'd be firing at would be the British. When he did face them across the battlefield, he remembered the rout of the redcoats that shattered the myth of their invincibility. Three years later following the French defeat at Louisbourg, the redcoats and colonials including Washington launched another assault on Fort Duquesne. A different route resulted in another tough march along a hacked-out road through woods, over swamps and up precipitous hills. On November 5 after an exhausting trek in mud and torrential rain, a council of war was called. It was decided that the expedition should proceed no further that year. Shortly thereafter an unbelievable report was received that the French and their Native allies were abandoning Fort Duquesne. The French could no longer mainain this advanced position because the British had captured Fort Frontenac. The British force decided to attack the weakened garrison and on November 24 as they approached the bastion, a great explosion rent the sky. The French had destroyed Fort Duquesne. Fort Duquesne - Its evacuation and destruction.

A day later the British reached the ruins which they renamed Fort Pitt, the present site of Pittsburg. The middle American colonies sang songs of praise for the French forces that terrorized the frontier had at last been defeated and driven out. Washington was heralded as a hero. A Presbyerian minister's comments at the time were prophetic. George Washington Raising the British Flag at Fort Duquesne (renamed Fort Pitt)

Fast forward twenty years to 1775. The 13 Colonies had decided upon independence and prepared themselves for the conflict to come with Mother England. The Second Continental Congress faced an important decision: who was to lead the American army against Britain's military might? The focus fell on George Washington. Despite one member from Washington's own colony of Virginia, who declared that while he was a decent chap, Washington was no warrior and had lost every big battle he had ever been in, the Second Continental Congress on the 15th of June, 1775, appointed Washington "General and Commander in Chief of the Army of the United Colonies" on the 15th of June, 1775. Washington formally took command on 3 July 1775 and set out to create a fighting force out of fractious, unruly recruits. He described his soldiers as "a mixed multitude of people ... under very little discipline, order or government." Admiral Lord Richard Howe

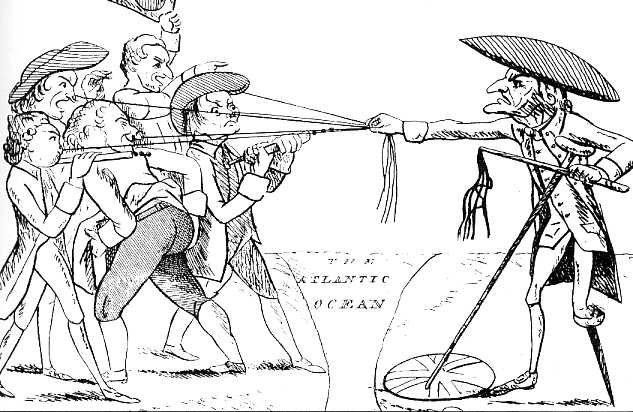

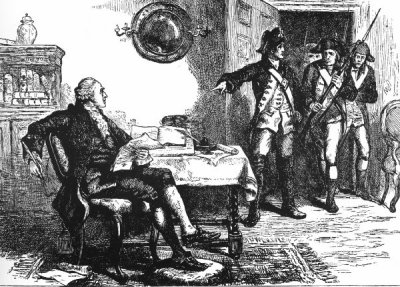

Incensed by such silliness, Howe declared, "We strove as far as decency and honour could permit to avert bloodshed and yet it seems beneath the head of a banditti of rebels to treat with a representative of the king because it is impossible to give all the titles the poor creature requires." When the British finally yielded and addressed the letter to 'General' Washington, a triumphant Washington asserted that very act represented recognition of the illegal rebel government and its independence. Angry Old England trying to restrain the rebelling colonists - 1776

Once war began there were some in and out of the British parliament who openly supported the success of the colonies. Some of them resented a war with 'other Englishmen' whose cause they considered to be just. Others saw support for the rebels as a way of limiting the growing power of the king. They opposed the war which the sovereign supported because they objected to George III's persistent efforts to increase the authority of the crown. Because the king's power was indefinite, George considered it infinite. British opponents of the American conflict saw this as a way of restricting the sovereign's power. A few actually believed the American cause would ultimately prevail and openly declared this early in the conflict. One of the most distinguished of these latter outspoken individuals was William Pitt the Elder, the great Earl of Chatham. William Pitt the Elder (Lord Chatham)

In November 1777 Pitt rose in the House of Lords and appalled the other peers with his declaration. Four years later in January 1781, William Pitt's son, William Pitt the Younger, took his seat in the House of Commons and in his second speech to the House, he too denounced the war with America William Pitt the Younger

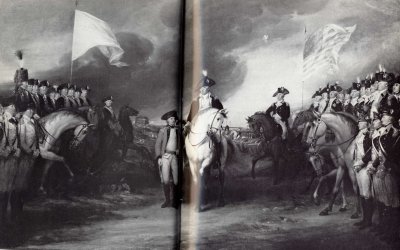

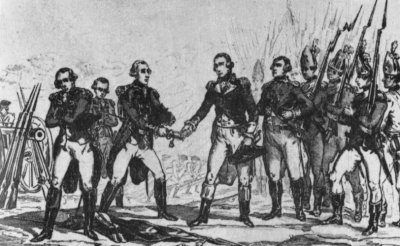

The great British parliamentarian, Edmund Burke, also opposed the war and argued eloquently for understanding and compromise at this critical time. On March 22, 1775 he urged his fellow Members of Parliament to remove the Americans' causes of complaint. Then he spoke the words that resound in history. Two hundred and one years later on the occasion of the bicentennial of American independence, Queen Elizabeth II recognized the failure of Britain's leaders to listen and learn from Pitt and Burke. At Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on July 6, 1976, she said, It was, indeed, "a government of little minds," but it was not only lacklustre leadership by British politicians that accounted for the loss of the colonies. The sovereign's stubborn predecessor, George III, was the principle figure in the fiasco, since in the final analysis he called the shots. The full extent to which the king actively directed the repressive policies on the colonies became clear many decades later when the archives at Windsor Castle were opened. Notwithstanding this imperial ineptitude, Britain's colonial catastrophe was directly due to the incompetence of the British commanders in the field - Howe, Gage, Clinton, Cornwallis and Burgoyne. It is the fate of generals that their heroics or blunders determine the outcome of wars and British generals committed their fair share of the latter. General Thomas Gage dilly-dallied and gave George Washington time to build a U.S. fighting force. William Howe sacrificed 1,054 men to gain useless Bunker's [Breed's] Hill. On two other occasions he travelled by long sea voyages when direct overland attacks might have turned the tide. Gentleman Johnny Burgoyne paraded his overburdened army pointlessly through dense wilderness before being forced to surrender his entire force at Saratoga. Charles Cornwallis repeatedly let Washington elude him before finally shamefully surrendering to him at Yorktown. The Surrender of Cornwallis [British Brigadier Charles O'Hara on foot left of centre; Cornwallis pleaded illness and did not appear. French officers on left; American's on right. Since O'Hara was Br. second in command, Washington delegated his second in command, Major General Ben Lincoln on white horse, to preside.]

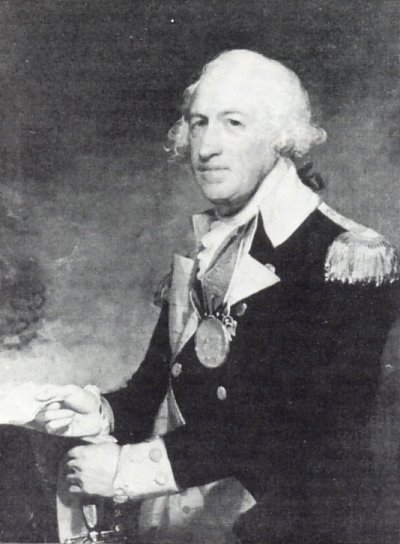

Lieutenant General John Burgoyne was a man of many talents, but he has the misfortune to be remembered during the American Revolution chiefly for his surrender at Saratogo which led to the loss of the colonies. While he dubbed the rebels "rabble in arms" and "a preposterous parade," he was not unsympathetic towards their plight. In fact, his sentiments towards them might even be described as friendly and although he fought them without a twinge of misgiving, his heart was never fully in the fight. In a long laboured letter he confessed this lack of enthusiam to his sovereign. Notwithstanding Burgoyne's amiable attitude towards the Americans, the king approved his command of a major offensive against them planned by the general himself. George III was delighted with Burgoyne and his strategic plan and ordered Lord George Germain, Secretary of the Colonies, to see that it was carried out. "Meticulous instructions insulting in their minuteness" were forwarded by Germain to Sir Guy Carleton, governor of Quebec, who claimed credit for the strategy which Burgoyne adopted as his own of separating New England from the other colonies. Carleton had expected to be placed in command of the enterprise. Instead he was replaced as commander of the 1777 campaign by his deputy, Burgoyne. Carleton was bitter about his replacement and informed Germain that "since you have taken the conduct of the war entirely out of my hands," he would resign. Despite King George's animosity towards Carelton for having once disparaged "the alien Hanoverian dynasty" from which George had sprung, the king refused to accept his resignation. He was ordered to provide every assistance necessary to mount, launch and sustain Burgoyne. Carelton, still burning from being bypassed, courtly complained that he could not spare the troops and did little to bolster Burgoyne. Sir Guy Carleton is one of the great figures in the history of the Canada. The Seven Years' War opened the path of advancement for him. He rose from lieutenant to acting brigadier general and was wounded on the Plains of Abraham. Wounded twice before the war ended, he was named Governor of Quebec in 1768. His influence in shaping the country's future destiny was greater than that of any other individual of his time. His instinctive judgements were quick, but shrewd, clear, firm and far-sighted. He foresaw the discontent of the British colonies to the south and believed France would become not their enemy but their ally, friend and protector. He said Canada would be invaluable in that instance and would support British interests on this continent. He was disappointed to discover, however, that when war came, the Canadians chose not to become involved. He was also near-sighted when he opposed representative government. Carleton never compromised and was contemptuous of any who questioned his authoriity or opposed his will. Carleton was an able officer who had distinguished himself in battle. When Wolfe insisted on Carleton's appointment to his staff, the King refused and only grudgingly agreed after Pitt pleaded although the king was sure no good would come of it. The King was habitually wrong. Carleton served Wolfe as quartermaster general at Quebec with great skill, was wounded during the battle. He was willed by his commander all of Wolfe's books and papers.

As governor general of Canada, Sir Guy Carleton fought and defeated an American force dispatched by Washington and led by Brigadier General Richard Montgomery and Benedict Arnold to take Canada and make it the fourteenth state. Heroic rendering of the Death of Montgomery. (It was painted nine years after his death at dawn during a snowstorm.)

"Sir," said the letter from General George Washington, "you are entrusted with a command of utmost consequence to the interests and liberties of America." These words were addressed the whirlwind warrior of energy, Benedict Arnold. With a thousand men, Arnold set out to conquer Canada. Awaiting him with a melancholy mask of resolve was Sir Guy Carleton. Ice had set in and if Canada was to survive he would have to fight them with the few forces available. It would all be decided at Quebec. Carleton fought with the little he had and then bided his time behind the walls of Quebec until America's chance had come and gone. In May the ice of the St. Lawrence melted and ships arrived from England with a major field army. The Americans fell back from Quebec and then Montreal in a retreat that became a rout. Later as Lord Dorchester, Carleton continued his long and dedicated service to this country. A major architect of Canada, he was not a man who won friends or influenced people easily. He was too grave, too inflexible, too sure of his own virtue, too pompous. As a result he attracted little thanks and less recognition for the great contributions he made to Canada. Sir Guy Carleton

Lieutenant General John Burgoyne

Bearing the sovereign's seal of approval, sprightly, handsome, jaunty Johnny Burgoyne arrived at Quebec on 6 May, 1777 aboard the frigate Apollo. When he learned that the British garrison in Boston was being besieged by Americans, he declared to his cheering troops, "What! Ten thousand peasants kept five thousand King's troops shut up? Well let us get in and we'll soon find elbow room." Burgoyne's bravado was the subject of deprecating humour at home in England. Swaggering even on paper, Burgoyne bragged in letters home about his successes before he had achieved them. "Have you read of General Burgoyne's boast in which he almost promises to cross America in a hop, step and a jump." They howled at home at his pomp. Despite his pomposity, Burgoyne was popular with his troops. Generals are exalted persons and Gentleman Johnny, as he was referred to with affection by his soldiers, was the most exalted of all. He treated his men like human beings unlike some other officers who were indifferent to them and their welfare. Burgoyne had courage and "shunned no danger, his presence and conduct animating the troops who greatly loved the general." At fifty four he had a brilliant military career behind him as a light dragoon officer dashing about the open plains. His confidence was unbounded. He bet a colleague that he would be home victorious from America by Christmas Day, 1777. The government was looking for action and Burgoyne planned to deliver it. British strategy was to divide and conquer. The plan to detach New England from the rest of the colonies was claimed by Burgoyne and he was delegated by the king to command the operation. It was designed to split the rebellious colonies in two down the natural fault line of the Montreal-New York waterline. Burgoyne proposed a two-fisted attack from Canada into the upper Hudson Valley. His blow from the north attacking down the Hudson River from Canada was to be perfectly time with a right fist from General Sir William Howe punching up the Hudson River from New York City using the British fleet.

General Sir William Howe

Burgoyne's troops were to cut out the American forces waiting at Ticonderoga and with the head of the rattlesnake severed, the body would then die. The rebellious colonies would be split in half thus ending the revolution. Burgoyne's magnificent army - the finest-equipped foreign force ever to invade the United States - had everything in its favour when it began its march: excellent leaders, high morale and a large body of Aboriginal scouts. The enemy presented a confused and ill-organized opposition, "a preposterous parade of military arrangement" lacking both men and supplies. To the sound of martial music from brass bands, fifes and rolling drums, the Grand Army of Burgoyne departed up Lake Champlain by boat and by land on the 20th of June 1777. Gentleman Johnny lived and travelled in style. Twenty-six wagons were allocated for the baggage of Burgoyne and his senior staff: tents, camp beds, blankets, cooking stoves, dinner china, silver plate and crystal, wines, champagne, personal supplies and uniforms. At times they covered as little as a mile a day. Social notes kept on the commander recorded that "General Burgoyne was very merry and spent many an evening singing and drinking." Burgoyne's luxurious living never tarnished his reputation with the troops. The popular commander possessed a winning manner in his person and appearance."which causes him to be idolized by the army." On every occasion he was "the soldier's friend," knowing so very well that success depended on the spirit of the troops under his command. Burgoyne's army comprised some seven thousand troops consisting of seven British regiments, four batteries and "the hireling sword," seven German regiments wearing huge headgear, great boots that came up to the thighs and heavy sabres. Canadian militia in buckskin and homespun and Native warriors in war paint brought Burgoyne's forces to a total of 8000 officers and men. Burgoyne cautioned his Native allies that only military men were to be attacked and all civilians no matter how curt and crusty were not to be harmed. Lieutenant General John Burgoyne

Burgoyne Addressing Native Warriors

As a military man Burgoyne had experienced more than his share of good fortune. A horse had been shot from under him, his waistcoat had been ripped by a rifle ball and he had been forced to remove his hat to rearrange a plume severed by a finely aimed shot. Nicknamed 'General Swagger,' Burgoyne's luxurious equipment alone required numerous carts to carry his personal supplies. Unfortunately, this London fashion plate who was so preoccupied with his appearance and creature comforts was unequal to the task he had undertaken despite accurately predicting the difficulties he would face. "Burgoyne indicated the purely military difficulties of the advance so clearly that a wiser man might well have hesitated to incur them." 'General Swagger': Gentleman Johnny Burgoyne [1722-1792]

On July 1st Fort Ticonderoga, from the Aboriginal word Cheonderoga meaning clashing waters, came into view. The walls of the stark, grey foreboding fort were softened somewhat by green growth and shaded by the shadows of the forest. The water's edge was guarded by a tangle of undergrowth and an abatis - a rampart of felled trees whose sharpened boughs pointing outwards. The fort was fortified by some 2000 Americans soldiers commanded by Major General Arthur St. Clair, a tall, quiet Scot in his forties with blue-grey eyes and light chestnut hair. Arthur St. Clair

'Fort Ticonderoga Restored

Fort Ticonderoga was dominated by a steep, 750-foot,conical craig known by various names - Rattlesnake Hill, Sugerloaf Hill and Mount Defiance. The fort's defenders believed the hill was impossible to climb let alone fortify, its steep, forested height accessible, they said, solely by goats. One of Burgoyne's engineers saw in the summit a way to fire on the fort. "Where a goat can go a man can go, and where a man can go he can drag a gun." They set about to prove his point and devised a route on which to drag to the crest two twelve-pounders. The distance to the fort was about a mile, a long way for even the biggest cannon. Because of the height, however, they could lob shells at the fort and even if the balls did little damage the psychological effect would be unnerving. On the morning of July 5th the rising sun flashed suspiciouly from the top of Sugarloaf. This alerted the Americans who subsequently saw redcoats moving about on the summit. St. Clair took one look and said, "We must away from this because our situation has become desperate." His officers supported his decision unanimously and abandoning their boast to hold the post to the last, the Americans left under cover of darkness. They stole away in the night, leaving behind in their haste cannons, ammunition, a large quantity of stores and their whole stock of live cattle. The British walked into the deserted base on July 6. This capture without cannons brought great joy to the English and blackest despair to the Americans. The British had pulled off a master plan by scaling the steep mountain that overlooked Ticonderoga permitting its unexpected capture. Ticonderoga, an important post because it was the back gate to the Atlantic colonies, was taken without a fight. It opened a corridor for Burgoyne and his invading army from Canada and should have permitted them to push south to New York City, slicing the rebel army in half and isolating New England, an over-arching objective of British war policy. Burgoyne reported to Prime Minister Lord North that his capture of Ticonderoga had been accomplished "while never menacing and without cannon firing on his part." The rapid withdrawal of the American forces increased Burgoyne's unwarranted contempt for the oolonists. When word reached England of Burgoyne's triumph at Ticonderoga, George III ran to his wife, Queen Charlotte, shouting, The first round had been won at Ticonderoga by Burgoyne, but blunders awaited. Certain of his destiny, he envisioned a sweeping victory and the highest honours for himself. With this favourable future awaiting him, Burgoyne designed his downfall by plunging into the swampy wilderness south of Lake Champlain instead of taking the easier roundabout route by Lake George. He would have been wiser to load his troops, artillery and baggage onto boats and float safely down to Fort George and on to the Hudson River. He chose instead to press on through virgin forests he himself thought "impassable." Clouds of buzzing, biting black flies savaged the exhausted soldiers perspiring profusely in their waist coats, tight breeches, high-buttoned gaiters and heavy, long-tailed blue and scarlet uniforms. With backs bent by their sixty pound burdens of musket, bayonet, canteen and cartridges, the Grand Army, some sickened by the bite of malarial mosquitoes, undulated like a giant serpent through the heavy, humid undergrowth, slipping and sliding in the mud as they made their way through land alive with slithering, poisonous snakes. Burgoyne's Route to Ruin

Burgoyne carried too much of some things and not enough of others. He had too many howitzers, mortars and cannons for a country without roads. The constant necessity of finding fresh horses and forage for this large train of guns, ammunition tumbrels and carts placed a severe strain on his transportation system. He had so little food his forces were on half rations. They found no local sustenance and support for "the liberating army" for any Loyalist sympathizers had been routed by the rebels who then burned their crops and farms and fled. Any Americans who remained were fervently antagonistic, their hostile attitude heightened by their hatred of the Hessian troops. "The bulk of the countryside is undoubtedly with Congress and is the most active and rebellious race in the continent. It hangs like a gathering cloud upon my left. Wherever the King's forces appeared, American militia numbering three to four thousand assemble within 24 hours. They bring with them their subsistence and as soon as the alarm is over they leave taking the cattle and corn with them." Initially contemptuous of the colonial clods who opposed him, Burgoyne revised his opinion as time wore on. "Each rebel soldier is his own general who will turn every tree and bush into a kind of temporary fortress from whence when he hath fired his shot will skip to the next." Burgoyne faced the problem of supplying his large force from a base 130 kilometres away across the terrible terrain through which he was travelling. Had he chosen to move without his heavy guns and burdensome baggage, there was no force between him and Lake Champlain that could have conquered him. He chose, however, to lumber along in pursuit of his fleetfooted foe whose flight ended when the Americans had enticed Burgoyne two hundred miles from his base. Then they turned to confront him. Lord George Germain

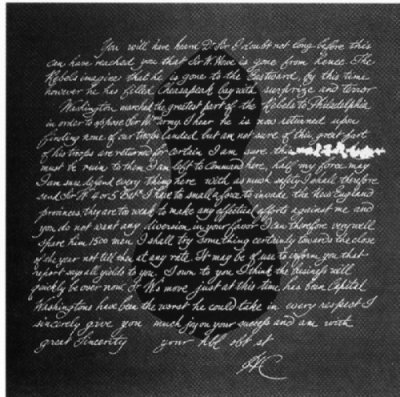

Where was Howe? Lord Germain, an arrogant, hot-tempered, obstinate man who did not like Burgoyne, had promised Burgoyne he would write to Howe to acquaint him with his role in the plan. Whether or not this happened is open to question. One source says Germain neglected to write this letter. Another says it was sent but arrived too late. Still another indicates that Howe received the message, but decided while he was awaiting the rendevous with Burgoyne to attack Philadelphia. Although Howe held Burgoyne's destiny in his hands, he decided to sail in the opposite direction where he forced Washington's retreat. Howe's victory resulted in a flanking party of the 33rd Regiment taking "horse, arms, colours [*] and drums" of the rebel colonel of the Delaware Militia. If Howe as some said did not receive the letter, Germain was criminally negligent. Of this flagrant failure to notify Howe, one historian wrote:"Never was there a finer example of the art of organizing disaster. If Germain did inform Howe and if Howe had come up the Hudson to unite his powerful army with that of Burgoyne's, success might have been theirs and they could have shared the glory of winning the American Revolution. Howe boasted of his own "very important and brilliant success," while disparaging word that Burgoyne's situation was very critical. Howe declared, "the Americans are ever ready to propagate the most direct falsehoods upon every occasion." Prior to leaving to attack Philadelphia, Howe wrote to his second in command, Sir Henry Clinton, , "If you can make any diversion in favour of General Burgoyne's approaching Albancy, I need not point out the utility of such a measure." Clinton accepted this as a permissive, casual suggestion and took no action. He later wrote to a fellow officer, "I have not heard from Howe for six weeks and have no orders to co-operate with Burgoyne." Despite this, however, on September 10 Burgoyne received a letter from Clinton whom Howe had left in command in New York with a small force. Clinton's letter was coded in such a way that it could be understood only if the receiver knew that the real message was enclosed within an hour glass shape in the centre of the page. Clinton's message indicated that he had received some reinforcements and would shortly start up the Hudson to meet Burgoyne. His forces were weak, however, and he was unable to force his way far enough up the Hudson to meet with Burgoyne. Coded Letter within the hour glass from Clinton to Burgoyne

As soon as Washington realized that there would be no meeting of Burgoyne and Howe, he seized the chance to strike. "Now, let all New England rise and crush Burgoyne." Burgoyne's army clashed with the American force of some 7000 led by Major General Horatio Gates at a place called Saratoga. The battle became an intense seesaw conflict with the advantage veering back and forth between the two forces. Major General Horatio Gates

The sabre, pike, bayonet and rifle butt were in full play as men fell under the blows or were cut down. The British assault was savage but losses were heavy and those who survived were exhausted, hungry and disheartened. The bushes and brambles of the wilderness had reduced their uniforms, the pride of the regulars, to tatters. Their food was salt pork and flour and even that was running out. Soon their rations were reduced by one-third. The grass in the meadows was very soon eaten by their horses and their was no more forage to be had. Many horses died of starvation. The 8000 rank and file with whom Burgoyne had appeared before Ticonderoga had now become 5000. Even this number was continually sapped by desertions. It was easy enough to disappear into the forest. Every man in camp must have known the invasion had been cancelled and that even retreat was hardly possible. To these discouraged men, The Americans gave no rest. Burgoyne described the continual torment."It was the plan of the enemy to harass the army by constant alarms and their superiority of numbers enabled them to attempt it without fatigue to themselves. I do not believe that either officer or soldier slept duing that interval without his clothes, or that any general officer or commander of a regiment passed a single night without being upon his legs occasionally at different hours and constantly an hour befor daylight." Benedict Arnold detected that Burgoyne's centre was weakening and demanded that 'Granny' Gates, with whom he was constantly clashing, release reinforcements so Arnold could take advantage of the situation. Gates agreed to release a brigade, but ordered Arnold not to return to the battle. Disregarding Gates's order, the fiery comet of the battlefield that all soldiers looked to dashed onto the battlefield. Arnold, whose enemies referred to him as a "horse jockey" rode extremely well. When he rode before his regiment cheers filled the air and at the head of his troops he became the real hero of Saratoga. Later he was wounded and suffered a badly broken leg when his horse fell on him. He refused amputation and survived the wound. Arnold's leg was lauded by Americans, while the rest of him suffered as a synonym for traitor most foul. Burgoyne meanwhile faced overwhelming odds while desperately awaiting word from Clinton. He hurled his men against the Americans in a wild, frenzied but futile fight. Benedict Arnold at Saratoga

Burgoyne's courage was never in question. According to one of his sergeant's, he "behaved with great personal bravery, he shunned no danger; his presence and conduct animated the troops; he delivered his orders with precision and coolness and in the heat, fury and danger of the fight maintained the true characteristics of a soldier - serenity, fortitude and intrepidity." Out-numbered, out-fought and finally out of fortune, Burgoyne on the morning of the 13th of October called a general council of all his officers. He accepted full blame for their situation and reviewed their options. "Would surrender on advantageous terms be disgraceful?" he asked. The answer was a unanimous "No." Was such a capitulation necessary? To this question all officers pledged their loyalty to "do or die." After hearing out their homage to him, Burgoyne decided to prevent the carnage to come by exhibiting sanity, good judgment and great commonsense. He entered into negotiations with Major General Horatio Gates and asked for "a cessation of arms." There was plenty of bravery and gallantry to go around on both sides. Early in the morning of the 14th, a drummer in a yellow coat marched boldly out, tightened the soggy head of his drum and beat out the parly. Negotiations were long and difficult. Astonishingly, Gage agreed to all Burgoyne's terms including his demand that nowhere in the Articles of Agreement should the word 'capitulation' appear, the word 'convention' to be used instead. Loyalists were to be respected and considered British subjects and sent back to Canada. Officers were to retain their small arms and their baggage was not to be searched. A very decisive event in history ended on this bizarrely courteous note. Gates wrote exaltantly to his wife: "If Old England is not by this lesson taught humility, she is bent on her ruin." Burgoyne, however, showed no humility, admitted to no errors and declared that if all his troops had been British, he would have fought his way through. Ceremonies were set at Saratoga for Friday, Oct. 17, 1777. British and German soldiers formed ranks, and to the crisp, clear orders shouted on that fine, fall day, they grounded the tools of their trade and as prisoners of war, 4693 men marched into a long period of captivity in Cambridge, Massachusetts. John Burgoyne appeared immactulately dressed in full ceremonial uniform, "having bestowed so much care on his whole toilet that he looked more like a man of fashion than a warrior." When the two generals approached to within a sword's length, they reined up and halted. Presenting his sword to Gates, Burgoyne raised his plumed hat gracefully and said, "The fortune of war has made me your prisoner." Gates replied, "I shall always be ready to bear testimony that it has not been through any fault of your excellency." Gates returned Burgoyne's sword and invited Burgoyne to a drink of rum and water along with a meal served on two planks laid across beef barrels of ham, beef, goose and boiled mutton, the two laughing all the while at various witticisms. At the end when Burgoyne was asked to propose a toast, he stood and with glass in hand after a moment's pause declared, 'George Washington'. In return Gates rose and toasted 'King George III'. Gates was generous in his praise of Burgoyne, subsequently writing to him, "If courage, perseverance and a faithful attachment to your prince could have prevailed, I might have been your prisoner." Burgoyne's Surrender

Burgoyne's Surrender

Major General Horatio Gates

In His Own Words

"I may point out to the public heroic young Colonel Washington, whom I cannot but hope Providence has hitherto preserved in so single a manner for some important service to his country."

In His Own Words

"I may point out to the public heroic young Colonel Washington, whom I cannot but hope Providence has hitherto preserved in so single a manner for some important service to his country."

In His Own Words

"My Lords, you cannot conquer America. You may swell every expense, pile and accumulate every assistance you can buy or borrow, traffic and barter with every little pitiful German prince that sells or sends his subjects to the shambles, but your efforts are forever vain, doubly so from this mercenary aid on which you rely, for it irritates to an incurable resentment in the minds of your enemies. If I were an American, as I am an Englishman, while a foreign troop landed in my country I never would lay down my arms, never, never, never. I rejoice that America has resisted." Pitt urged Britain to show prudence and good temper and the Americans would reciprocate.

Be to her faults a little blind.

Be to her virtures very kind.

In His Own Words

"as most accursed, wicked, barbarous, cruel, unnatural, unjust and diabolical."

In His Own Words

"Magnanimity in politics is not seldom the truest wisdom; a great Empire and little minds go ill together." Unfortunately, he had the voice but not the votes.

In Her Own Words

"We lost the American colonies because we lacked the statesmanship to know the time and the manner of yielding what it is impossible to keep."

In His Own Words

"I have beaten all the Americans."

The precipitate evacuation of Ticonderoga, that famous fortress which bulked so large in the imagination of the Americans, had caused astonishment and spread dismay throughout the country. A committee of the Congress was appointed to look into the conduct of the commander at the time of the surrendering of Ticonderoga.

Each party scorn'd for to give way, we fought like Britons bold,

Until the leaves with blood were stain'd our General then did cry,

It is diamond, cut diamond, fight on until we die."

Which they had burnt as they had done all houses on their road,

The sixteenth of October was forc'd to capitulate,

Burgoyne and all his army there were our prisoners made."

Everyone was waiting to learn the result of Burgoyne's brilliant victory and when news of his catastrophic surrender on Oct. 18, 1777 reached England on December 11, 1777, the government "were in a state of great distraction." The defeat radiated shock waves in London and in Paris and resulted in the British thinking of getting out of the war and the French of getting in. King George in order "to disguise his concern affected to laugh," and this bizarre behaviour was considered by those present to be so offensive that the prime minister attempted to stop him. It was "Dreadful news indeed." In the House of Commons Edmund Burke was appalled.

In His Own Words

"A whole army compelled to lay down their arms and receive the laws from their enemies is a matter so new that I doubt if another such instance can be found in the annals of our history."

Lord Chatham's earlier warnings about the futility of the American war had come true. On learning of Burgoyne's defeat, he staggered into the House of Lords and lashed the government for bringing "ruin to our door." He thundered warnings about the French preparations for war and recommended to the King "an immediate cessation of hostilities and the commencement of a treat to restore peace and liberty in America."Meanwhile in the House of Commons members reacted with shock and sadness at Burgoyne's defeat. Lor Germain acknowledged the "melancholy event though the recital must give me pain." Edmund Burke commented critically that "a whole army compelled to lay down their arms and receive laws - surrender terms - from the enemy was something new in the kingdom's history." "Dreadful news indeed," said the great historian Edward Gibbon, who had been elected in 1774 as a supporter of Lord North.

The Commons called for an investigation into how Burgoyne's campaign had collapsed. To the ministry's embarrassment Burgoyne himself on formal parole from his prisoner-of-war status by act of Congress arrived in England to take part in the what he expected would be caustic debates about his "warm skirmishes." Since to the king Congress was an illegal body, Burgoyne was still considered to be a prisoner of war and as such was refused admission to the royal presence. On May 26, 1778, Burgoyne, who was Member of Parliament, appeared dramatically in the House of Commons to defend himself. He never had to, however, for the motion for a committee of inquiry into Burgoyne's conduct, which was seconded by Burgoyne himself, was rejected by a vote of 144 to 96. On April 3, 1779 Congress directed Washington to recall Burgoyne and other senior officers on parole. Burgoyne appealled to his friends, and Burke wrote Ben Franklin to seek his release. Franklin replied that Congress was willing to exchange Burgoyne for Henry Laurens who was then jailed in the Tower of London. Laurens, who was ultimately exchanged for Corwallis, subsequently joined Franklin and other in settling the peace treaty which ended the American Revolution.

|

|

Edmund Burke |

The Saratoga surrender changed the whole course of the war. Framce was burning for revenge and when it began to appear that the colonies might just be able to prevail over Britain, French leaders decided to form an alliance with the revolutionaries. The French dreamed of recapturing Quebec and decided to do all in their power to make the break between Britain and her colonies irreversible. Power on the battle field resulted in power at the bargaining table. Following the British defeat at Saratoga, Benjamin Franklin informed the French foreign minister: "We have the honour to acquaint your Excelleny with advice of the total reduction of the force under General Burgoyne." After a full year of deflecting American requests for an alliance, Louis XVI two days after receiving Franklin's letter invited the Americans a gilt-edged paper to re-submit their request for a formal alliance. By 1780 Britain was virtually at war with the world. France, Holland and Spain were committed enemies and Russia, Prussia, Denmark and Sweden were leagued against Britain in "armed neutrality."

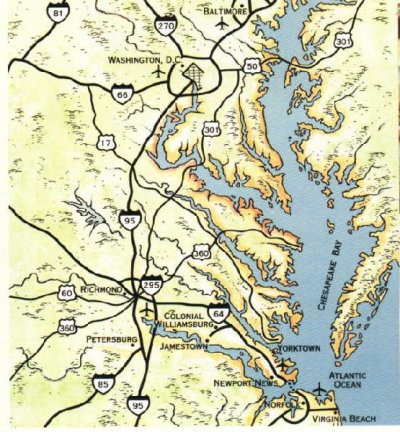

The defeat Lord Chatham had predicted came four years later. Lord Charles Cornwallis, whose army was still undefeated, was fortifying a post at Yorktown on the shore of Chesapeake Bay. As long as the British navy was master of the sea and could supply his needs, Cornwallis was able to defy his enemies. However, the French fleet under the Count de Grasse, a giant of a man who referred to six-foot three Washington as Mon Petit general, met and defeated the British fleet driving it back to New York. As a result the French now controlled the Chesapeake and immediately implemented a sea blockade of Yorktown while Washington's army barricaded Yorktown by land.

|

|

Yorktown |

It was not long before Cornwallis, whose forces who were without food and being battered unmercifully by fifty-two French cannons, was forced to report, "We cannot hope to make a very long resistance." .

|

|

Lord Charles Cornwallis |

In a letter to Cornwallis, General Washington declared that he wanted to stop "the useless effusion of blood." After only two weeks of feeble resistance, Cornwallis realized there was no hope for his army. As the sick and wounded multiplied by the hour, Corwallis asked his officers should they "Fight to the last man?" They said the men had done all that could be expected of them. "Surrender!" Cornwallis nodded assent. Deciding "it would be wanton and inhuman to sacrifice the lives of this small body of gallant soldiers," Cornwallis ordered a drummer - accompanied by an officer with a flag of truce - to mount the parapet and beat to "parley." On October 17, 1781, four years exactly after Burgoyne's surrender at Saratoga, Cornwallis sent the following letter to Washington.

"Sir,I have this moment been honoured with your Excellency's letter dated this day.The time limited for sending my answer will not admit of entering into the detail of Articles, but the basis of my proposals will be that the Garrisons of York and Gloucester shall be prisoners of War with the customary honours and for the convenience of the individuals which I have the honour to command that the British shall be sent to Britain and the Germans to Germany under engagement not to serve against France, America or their Allies until released or regularly exchanged. That all Arms and publick stores shall be delivered up to you, but that the usual indulgence of side arms to Officers and of retaining private property shall be granted to Officers & Soldiers and that the interests of several individuals in Civil Capacities & connected with us shall be attended to. If Your Excellency thinks that a continuance of the suspension of hostilities will be necessary to transmit your answer I shall have no objection to the hour that you propose. I have the honor to be your most obedient & most humble servant." (signed) Cornwallis

Simcoe's Queen's Rangers were among those surrendering and Simcoe asked Cornwallis to permit his largely Loyalist Rangers to quietly depart before the capitulation because he knew they would be treated as traitors and dealt with harshly by the American patriots. When Loyalist militiamen were captured by the American military, they were treated as traitors and subject to imprisonment or even execution. Britain on the other hand insisted on treating all patriot prisoners as prisoners of war and as such they were entitled to the courtesies of exchange and parole. A callous Cornwall refused Simcoe's request, declaring that all British soldiers would be treated equally. The Loyalists stood by in a rage while they saw men who had robbed and ravaged their homes paroled to freedom. One Loyalist writer commented, "In this war only those who are loyal are treated as rebels."

Simcoe kept tight rein on his emotions whenever he described the surrender at Yorktown in which his intrepid Queen's Rangers were included although they were not surrounded as was the main British force. The Queen's Rangers was an elite outfit which under Simcoe' command exercised a series of gallant, skilful, and successful enterprises against the enemy without a single reverse. They killed or captured twice their own number. Yorktown was the intrepid little unit's first defeat. They were few in number but an elite outfit which under Simcoe's command carried out a series of gallant, skilful and successful enterprises against the enemy without a single reverse. They killed or captured twice their own number and Yorktown was the intrepid little unit's first defeat.

At 10 a.m. on the 17th of October the guns fell silent, the only sound the British drummer boy beating a 'parley'. An American officer recorded, "I thought I never heard a drum equal to it. It was the most delightful music to us all." Talks were opened and two days later at noon on October 19th 1781 agreement was reached. The event was recorded in the diary of an American soldier. "Had the pleasure of seeing a British drummer mount the parapet and beat a parley and immediately an officer holding a white handkerchief made his appearance outside their works. The drummer accompanied him beating all the while. Our batteries ceased firing and an officer from our lines ran and met the other and tied a handkerchief over his eyes. The British drummer was then sent back and the officer conducted to a house in the rear of our lines."

On October 20th Cornwallis capitulated. When Corwallis learned that Washington would be taking his surrender, a mortified Cornwallis exhibited shameful military protocol by opting out of Britain's abject surrender to what he had earlier described as "an inferior foe." Claiming he was too ill to attend the ceremony, he dispatched Brigadier-General Charles O'Hara to carry out the distasteful duty.

With a roll of drums the British appeared, their colour guard carrying furled flags and their bands playing The World Turned Upside Down, an unmilitary, melancholy but most appropriate tune. They were led by O'Hara stiffly erect in his saddle, an extravagant-looking figure in enormous jack boots with double rows of curls hanging about his temples. As George Washington watched from his great bay horse, O'Hara tried to surrender his sword to Washington who anticipating what he was about to do said, "Never from such a good hand." O'Hara then gave it to General Benjamin Lincoln who had been delegated by Washington to receive it. The Americans and their French allies formed two lines. The French soldiers, resplendent in white broadcloth uniforms, "displayed a martial and noble appearance. The Americans, few of whom were dressed in uniforms, stood proudly erect beaming with satisfaction." Between their lines broken-hearted British soldiers wearing for the occasion newly issued red coats marched dejectedly.

|

|

Cornwallis Surrender |

|

|

Cornwallis Surrender |

|

|

Cornwallis Surrender |

In a nearby field a squadron of French hussars formed a circle within which the scarlet-coated British and Hessians brilliant in blue and green piled their arms. The Hessians stacked their guns neatly. The British, some of whom were weeping, moved along slowly flinging their arms angrily to the ground in a disorderly crash. All the while the several British bands brought the American Revolution to a close. The tune was doubly appropriate because it was first performed on a London stage in one of John Burgoyne's comic operas.

The World Turned Upside Down.

"If ponies rode men and flowers found the bees;

And grass ate cows and cats were chased by mice,

And if summer followed spring 'stead of the other way around;

All the world would be upside down."

An American fife and drum band played Yankee Doodle Dandee, the song that had been transformed from a British taunt to a rousing rebel anthem. Washington, who found no ringing words to celebrate his emotions on this momentous occasion, uttered only a few clichés about "a glorious event" and "an important success." Some 7241 British and German soldiers guarded by the militia were marched off to prison camps in Virginia and Maryland. Cornwallis and his principal officers were promptly paroled and allowed to leave for New York. Prior to departing they dined for several days at the tables of Washington, Rochambeau and other American and French officers.

News of the surrender was quickly dispatched throughout the country by the fastest horsemen. Before long night watchmen walking the streets cried out the time and the news. "Past three o'clock and Cornwallis is taken." The victory was hailed with rowdy rejoicing and exuberant celebrations swept the colonies. Incredulous Loyalists found it hard to believe and wondered and worried about the future that faced them. An immediate concern was the preservation through the night of their property from the uproarious rebels. They accomplished this by illuminating their windows to give the impression that they too were celebrating the American victory. Mobs roamed the streets looking for any unlighted Loyalists' lodgings which they promptly ransacked and robbed. One Loyalist recorded his relief. "We were fortunate not to see the furniture cut up and goods stolen nor been beat nor pistols pointed at our breasts."

Jubilant American citizens were permitted three hours in which to "illuminate on the Glorious Occasion."The following handbill authorizing the people to celebrate by lighting bonfires was issued at General Washington's order.

Illumination

Colonel Tilghman, Aide de Camp to his Excellency General Washington, having brought official accounts of the SURRENDER of Lord Cornwallis and the Garrisons of York and Gloucester, those Citizens who choose to ILLUMINATE on the GLORIOUS OCCASION, will do it this evening at Six and extinguish their lights at Nine o'clock. Decorum and harmony are earnestly recommended to every Citizen and a general discountenance to the least appearance of riot. (October 24, 1781)

|

|

Illumination |

Although substantial British and Hessian forces still remained in the field, Cornwallis's capitulation was decisive. The defeat broke the resolve of the British to continue the war and convinced them that the effort to overcome the Americans was too difficult and too expensive to continue. In a huge country with a populace so committed to their cause, the expense of supporting a great army 3000 miles away was becoming an intolerable financial burden to an already debt-ridden treasury.

When news of the capitulation of Cornwallis reached England, it hit Prime Minister Lord North "like a ball in the breast." The distraught politician paced about his room exclaiming in tormented tones,"O Lord! It is all over!" King George was also stunned by the news but vowed to carry on the war "though the mode of it may require alteration."

|

|

Lord North |

Throughout England public meetings demanded peace and Parliament reflected this desire. Lord North wrote to George III informing him that both royal policy toward America and his attempt to establish the supremacy of the king over Parliament must cease. "Your Majesty is well apprized that in this country the Prince on the throne cannot with prudence oppose the deliberate resolution of the House of Commons. Parliament has uttered their sentiments and their sentiments, whether just or erroneous, must ultimately prevail. Your Majesty can lose no honour if you yield."

Yield he did. Five and a half months after Yorktown Parliament on March 4, 1782 started procedures to recognize the victory of "the revolting colonies." The debacle later forced Lord North to resign.In March, 1782 Parliament authorized a subdued sovereign to seek peace with the colonies. The House of Commons declared "it would consider as enemies of his Majesty and the Country all those who should advise or attempt the further prosecution of offensive war on the Continent of North America for the purpose of reducing the revolted Colonies to obedience by force." England asked for terms.

Burgoyne attempted to defend his defeat. He said had he not been ordered to meet with Howe, he would have returned to Fort Edward where he would have been secure "until some event happened to assist him." He felt bound, however, to plod onward to "force a junction with Sir William Howe."

|

|

Cartoon depicting the 13 Colonies dumping Great Britain |

Even before the muskets were muzzled and Cornwallis had capitulated, the American Congress had appointed the members of its five-man negotiating committee and instructed them to proceed to Paris and prepare to negotiate peace terms with Great Britain. The new nation to be named the United States of America entrusted its fate to five men: John Adams, John Jay, Benjamin Franklin, Henry Laurens and Thomas Jefferson. The directions given by Congress to this committee in June, 1781 were broad but not deep. They were to demand independence and sovereignty. As far as anything else was concerned, they were told to trust to their own wit, wisdom and sound judgment. They were given only one specific direction: "to undertake nothing in the negotiations for peace or truce without the French knowledge and concurrence." This deference to a foreign power was in recognition of the critical part France had played in America's victory over Great Britain. John Adams and John Jay, were appalled at being shackled to France, while Ben Franklin was pleased and felt French involvement "well and judiciously placed." Despite his warm words regarding "the generous and noble manner in which the French supported America," Franklin lost no opportunity to negotiate behind their back.