foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

LOYALISTS, PATRIOTS & TOM PAINE

History is an argument without end.

In times of political conflict, loyalty to one person may be treason to another. No where was this clash of convictions more clearly demonstrated than in the reactions of colonial Americans to the revolutionary writings of a man named Thomas Paine.

|

Now Boys!

Born in Thetford, England and lived for a time in Lewes, [*] the free thinker, Tom Paine, went to the New World and with his pen changed the course of Western democracy. Paine was born on January 29, 1737 in a little market town some seventy miles northeast of London. A Norfolk Quaker, he grew up on a bare hill known as 'The Wilderness' facing the local gallows. While he attended a grammar school for seven years, he was almost self-educated, learning the basics of language and establishing the foundations of his literary skills. Thomas, a bright boy, was dismayed when his father withdrew him from school at thirteen to become an apprentice in the craft of making stays for corsets from whalebone, a series of stiff keratinous plates in the mouths of baleen whales used to strain plankton from seawater.

The following verse was written by Tom at the age of eight. It gives an early indication of the droll humour and simple, direct, down-to-earth language that in years to come permeated his militant pronouncements.

Epitaph to a Crow

Here lies the body of John Crow

Who once was high but now is low.

Ye brother Crows take warning all

For as you rise, so must you fall.

|

|

Statue of Thomas Paine in Thetford, England |

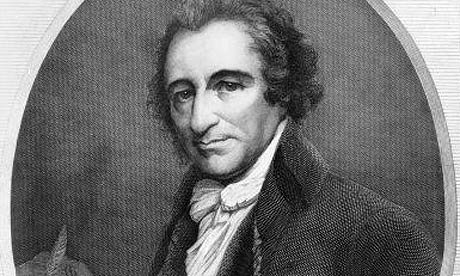

A portrait of Paine hangs in London's National Portrait Gallery. The painter, George Romney, was a fine artist and his portrait completed in 1772, provides insight into the character of the man. It depicts an individual in his forties with a ruddy complexion and a high forehead, thick and wavy, dark hair streaked with grey. His long, sharp, hooked nose was said to be pockmarked. His twisted mouth evinces a disdainful, maybe even mocking impression. It is said that his dark, striking, wide set, watchful eyes beneath heavy eyebrows revealed a man bent on a mission to agitate and incite others. A good place to start was his great contempt for governments that rested on hereditary privilege. This anger and resentment at the special few, fostered his fierce feeling that life for all should be based on individual merit, not ascribed social rank that set limits on an individual's achievement.

|

|

Thomas Paine |

Paine was a poor, disgruntled, ne'er-do-well Englishman, who failed at everything he tried. He stirred up trouble against his employer, attempted to organize his fellow workers and dared speak out for better wages ad working conditions. While agitating in England Paine met Benjamin Franklin who gave him a letter of introduction to friends in Philadelphia in which Franklin called Paine an "ingenious,worthy young man." Arriving in the 13 Colonies in November 1774 just prior to the outbreak of the American Revolution, Paine became a jounalist and launched a broadside against slavery. He became a pamphleteer, a propagandist, a person of pen and paper who wrote articles dealing with various controversial subjects. Paine, for whom life was either a daring adventure or nothing, was very mistakenly dismissed by Prime Minister William Pitt as an "unskilled rider,"

In the early stages of colonial unrest, Americans held powerful feelings of solidarity with the British Empire. If properly handled, they might have been "led by a thread and governed by a reed" for while they disliked the ministry, they esteemed the nation. During the 1st Continental Congress, John Adams said the delegates, who were "awash with burgundy at the elegant supper on the opening eve of the Congress," had toasted the union of Britain and the Colonies. Later Congress was reluctant despite its military preparations to break the line with Britain. It took a stranger, who had been in America only two years, to shatter the silence of restraint, awe and caution.

Tom Paine had no time for such tameness. Talk of conciliation with Britain was sickly and Paine's voice was soon to change the course of modern history. After the Battle of Lexington in April ,1775, Paine felt the need to challenge and change the world. He had a strong, radical, restless mind and quickly aligned himself with the cause of the rebels/patriots. Although his writing was dashed off and un-revised, it was filled with flaming phrases that set society afire and dominated and directed American thinking. Not only the message, but the modernist style of Commons Sense ensured its wide reading. Paine was the most prominent political thinker and writer during the revolutionary struggle against the British. It was said of him that "His conversation has much life. He has genius in his eyes." The brilliance of his quill made him a literary lion. Notwithstanding his lionization, this gadfly of government was often lampooned and it was in this spirit that the author of the "Life of Thomas Paine," released in 1793, printed on its front page this warning to all and sundry:

"Fear and improve," Paine pertly cries,

"I come to make the nations wise."

|

Paine's thoughts were razor sharp and his quill was quick and militant. He published a series of 16 pamphlets in seven years under the title The Crisis. The most sensational by far was Common Sense published on January 10th, 1776. "Turned upon the world like an orphan to shift by itself," it set America afire. The provocative publication, which defined arguments for the justice of the revolutionary cause, was the most effective pamphlet of the American Revolution. Almost over night the tiny booklet sold half a million copies and was reprinted in every colony. Pain's crisp, lean, lightening-quick sentences hammered out political points of view an audience of ordinary folk like him understood. But Paine was no ordinary person. Paine believed that liberty was connected with prose and that those who were unfriendly to citizens' liberty wrapped their power in pompous or meaningless phrases. He solved all problems by neglecting complexities. He invented a stirring style to capture the attention and secure the trust of audiences and "put it in language as plain as the alphabet" He tried to communicate complications simply and the power of such writing burned the page.

According to Thomas Jefferson, "No writer has exceeded Paine in ease and familiarity of style, in perspicacity of experience, happiness of elucidation and in simple and unassuming language." Paine's contribution to the public's awareness of the revolutionary struggle for Independence was to prove as great as George Washington on the battlefield or Ben Franklin on the diplomatic front.

Another of Paine's works The Rights of Man became the colossal best-seller of the 18th century. In it he declared, "the rights of man including their natural equality and individual liberties are God-given at birth and since they precede all forms of government they cannot be surrendered to those governments." He was praised with a song that was sung to the tune of God Save the King.

"God Save the Rights of man

Let despots if they can

Them overthrow..."

Paine kept nothing from his writings, donating all proceeds from the sale of his books to the revolutionary cause. Addressing his books to a mass audience unfamiliar with legal niceties, formal learning and complex rhetoric, Paine strove for simplicity and his words whipped up the wind and touched off a tornado that swirled through the colonies.

|

Common Sense was written for the common man and it became a best seller because it expressed in popular language that people understood, thought and felt. It represented the cry of a crusader, an "apostle of freedom," who used his pen to incite people to revolution. To say that it touched off a frenzy grossly understates its status. One hundred and fifty thousand copies were in circulation by spring. Paine's simple prose and sharp images aroused the passions and the powers of masses. "The period of debate is closed," declared Paine. It was time for Americans to fight for their freedom from two ancient tyrannies: monarchy and aristocracy. "All men being originally equal no one by an accident of birth has the right to set up his family in perpetual preference over all others." Washington said the "unanswerable tract" worked a magnificent change in the minds of men and women. It thrilled and terrified all who read it.

To those who advocated reconciliation with Mother England, Paine commented: "To be always running three or four thousand miles with a petition or a plea and then waiting four or five months for an answer was folly and childishness." It was, he claimed, a simple matter of common sense that an island could not rule a continent. Paine thought the sea ought to be England's boundary. When Ethan Allen, a frontier rowdy who led a band of ruffians called the Green Mountain Boys, was captured and imprisoned in England, his British captors tried to convince him of the futility of the revolution. His response was, "Consider you are but an island and your power has been continued longer than your humanity." The British knew this. They simply did not have the numbers needed and always had to seek the support of others to impose their will on those they sought to rule.

Memorable expressions flowed from Paine's pen.

* Not a place upon earth can be so happy as America.

* The birthday of a new world is at hand.

* The sun never shone on a cause of greater worth.

* If there ever was a just war, it is this one.

* Now is the seed-time of faith and honour.

* Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered.

* Character is easier kept than recovered.

* When planning for posterity, remember that virtue is not hereditary.

* It is not the affair of a city, a county, a province or a kingdom, but a continent.

* It is not the concern of a day, but of all posterity to the end of time.

* Oh ye that love mankind, dare to oppose not only tyranny but the tyrant.

* The cause of America is the cause of mankind.

Paine's plain, powerful prose caught many colonists up in a surge of patriotic emotion. "Independence," a word only whispered before now sprang easily and often to the minds and the lips of a great many people. Independence suddenly became supreme largely because Paine's words caused such a great stirring of patriotic emotion. His writing's "sublime aphorisms, exhortations and jeremiads" thrilled and horrified the masses and united most Americans in common hatred and fear of outside oppressors as well as inside dissenters.

Even Washington's woebegone warriors, whose energies were ebbing and fortunes flagging, were inspired by Paine's words to renew their fight for independence. Washington had another of Paine's essays, The Crisis, read to his soldiers. Its opening words worked magic on the men."These are the times that try men's souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will in this crisis, shrink from the service of his country; but he that stands it NOW, deserves the love and thanks of every man and woman." Washington called his words "flaming arguments, unanswerable reasons for separation."

While Paine believed that liberty entailed the right to tell others what they did not want to hear and believed in the principle that public authorities should be regarded as public property, he was most selective with his warrior words when it came to Washington. A bitter exchange over Washington's future broke out after the low point in the patriots' cause occurred at Valley Forge. Doubts were expressed about Washington's competence as commander and his replacement by Horatio Gates. was recommended. This was known as the Conway Cabal. Paine never mentioned the plots that existed to relieve Washington of his command, although he too had doubts about Washington's worth as a military leader. Nevertheless, Paine urged his acceptance "despite his want of military judgement."

Paine'e opinion of Washington waxed hot and cold. It appeared to boil over on the latter's retirement, when Paine said he prayed for Washington's imminent death and wondered, "whether the world will be puzzled to decide whether you are an apostate or an imposter, whether you have abandoned good principles or whether you ever had any." Paine was not alone in his denunciation of Washington. Editorials described him a "a tyrannical monster" and his farewell address "the ravings of a sick mind."

|

|

George Washington |

Paine's masterly appeal to the "simple voice of nature and of reason" became the soldiers' battle-cry. Kings owed their power to the people, said Paine, and when they became arbitrary, they could and should be swept away. Since previous, peaceful American protests had not been effective in resolving their grievances with mother England, the course of action was now clear. "'TIS TIME TO PART," bellowed Paine from the printed page.

American rebels gloried in the wonder and the wisdom of this man. >Another American, leader, John Adams, said that without Paine's pen, Washington's sword would have been raised in vain. Thomas Jefferson praised Paine's contribution to the American cause.

Paine very cleverly focused all his fury on one man: King George III. He quickly converted the king from the "Glorious George" of after-dinner toasts, to "the sullen-tempered Pharaoh," whom Paine labelled the "Royal Brute" of Britain. Paine said the monarchy supposed the body politic should be ordered hierarchically, so that every lesser unit should know its place beneath a ruler whose sanctity and power were inviolable. It was, said Paine, "something kept behind a curtain, about which there is a great deal of bustle and fuss and a wonderful aura of seeming solemnity, but if by accident the curtain happens to be opened and the company see what it really is, they all burst into laughter."

A large section of the American Declaration of Independence was devoted to the condemnation of the king as a tyrant. To the rebels/patriots, George III was the personification of all villainy, a disgrace to human nature, a fiend in human disguise. Historians disagree over the question of how far George III himself was responsible for the revolution's tumultuous events. While his ministers had to accept their share of the blame for what happened, George's arbitrary attitude and stubborn, petulant posturing drove the American colonists to rebel and perhaps even extended the length of the war.

When Paine, this "citizen of the world" declared "These are the times that try men's souls," his resounding words cut through the constitutional wrangles and stirred the emotions of Patriots and Loyalists alike but in completely contrasting ways.

The actual differences that divided the Tory Americans (Loyalists) from the Rebel Americans (Patriots) were minor and mainly ideological, and even these were slight and subtle. Both were like-minded on a good many matters. Both groups claimed the rights of Englishmen. Both protested against taxation without consultation. Both believed that a bond should exist between a ruler and those ruled. Both believed that tyrants should not be tolerated. Nor were there any sharp social, economic or cultural divisions between the two groups.

|

Jonathon and George

Given these common characteristics, it is instructive to examine their uncommonly different reactions to the ringing words of Paine's Common Sense. Rebels cheered and shared its sentiments; Loyalists laughed and ridiculed its recommendations.

|

Plaudits President Kudos King

|

Bust to Bullets

Common Sense had an extraordinary impact on Americans. In New York, a leaden statue of George III was melted down and moulded by the women of Litchfield, Connecticut into 42,000 bullets to fire at the British. To the rebels, Paine became the heavy artillery, the Voice of the Revolution. He rallied the wavering and gave strength to those who agreed that "nothing but independence could save America from ruin." Paine's words carried the cause of independence forward at a breathless pace and his services to the American cause were beyond measure.

What did Paine's pamphlet mean to the Tories, the Americans who chose to remain loyal to old King George? To these Loyalists, Paine was a dangerous demagogue doing untold mischief. They christened him "our hireling author, a true son of Grub Street," whose mission was to mislead and inflame the ignorant multitudes by exaggerating grievances and by outrageously magnifying the majesty and power of the people. The patriots' plea for liberty sounded hollow to the Tories they terrorized. The Loyalists' lamented,

"The Cry was for Liberty-Lord, what a Fuss!

But pray how much liberty left they for us?"

Initially, Paine was charitable towards the opponents of independence, believing them more "mistaken than criminal." Later he became more insistent."Who is for independence and who is not? Those who oppose must expect the more rigid fate of the jail or the gibbet." Supporters of the king were tools of a miserable tyrant. Paine was contemptuous of the Tories and mocked their contribution to the British cause. "General Lord Howe is as much deceived by you (Loyalists) as the American cause is injured by you. He expects you will all take up arms and flock to his standard with muskets on your shoulders. Your opinions are of no use to him unless you support him personally for 'tis soldiers not tories that he wants." Loyalists were American tory sympathizers whom Paine berated as cowards driven by "servile slavish, self-interested fear." Paine's watchword for treachery became the name Tory, a derisive epithet for anyone who opposed the revolution.

Unlike their revolting brothers, the Loyalists sought reason not riot. They believed that no matter what their complaints and criticisms of Britain were, they were better off personally and politically under a sovereign than they would be under the menace of mob rule. "If we are to be slaves, let it be to the lion and not to the lousy vermin of New England."

Upper Canada's first Lieutenant-Governor, John Graves Simcoe, had fought in the American revolutionary war and had seen at first hand what the frenzy for reform had done to British settlements in the 13 Colonies. He was determined to keep this "disease" out of his colony. He supported the view that Paine and all other inflammatory types were like a foul epidemic, which led inevitably to disorder, destruction and rebellion. Such miscreants had to be opposed by stern measures in the new colony, something that in the case of the 13 Colonies had unfortunately been delayed too long.

Two nations were nurtured by the American Revolution: the United States of America and Canada. It is interesting to note that today, their national characteristics tend to reflect their feelings they had towards Paine and his long ago preachings. The Patriots who became Americans eagerly espoused Paine's emotional messages to abandon former friends and the past with all its traces of petitions and dependence and to seek instead a bold, new future founded on the rights of the individual and their eternal quest for "life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness." The Loyalists decried this lofty litany, perceiving along with Samuel Johnson only hypocrisy in the rebels' cry for freedom. "Why is it that we hear the loudest yelps for liberty from the drivers' of slaves?"

The 'Loyalists' who became Canadians scorned Paine's call for confrontation and separation. They wanted to preserve peace and were determined to maintain the connection with their king and empire. Revered American words and phrases like "liberty," "democracy" and "we the people," had neither meaning nor merit in Canada, where the imperial tradition with all its ritual, pomp and ceremony was highly esteemed and thought worth preserving, even if this meant some few limitations on the rights and freedoms of the individual. This after all was a reasonable price to pay for the stability and tranquility that came with, "peace, order and good government."

What was Tom Paine's legacy to Upper Canada? "Because Loyalists were driven from their lands by those who boasted in extravagant terms of democracy and liberty as cures for all the ills of society, Loyalists who came to Canada loathed the very idea of democracy and for years to come, recoiled in horror at the mere mention of republicanism, the term itself synonymous with traitor.

Fortune flung Paine twice into the furnace of revolutions for they drew him like a magnet. "My country," wrote Paine, "is the world and my religion is to do good." His goodness almost got him guillotined when he visited France, where a revolution was raging. Initially, Paine was given a hero's welcome, made an honorary citizen and elected deputy for Calais to the National Assembly. However, his opposition to the decapitation of King Louis XVII infuriated the French republicans. As a result, Paine became demonized as an enemy of the state and was imprisoned where he languished for nearly a year. Despite his pleas to America for help, he received none from officials in Washington who denied Paine's claim that he was an American citizen. He was finally released at the request of James Monroe, the American ambassador to France. On his return to the United States, Paine castigated President Washington for leaving him imprisoned in France for 10 months and not recognizing him as an American citizen. About this there was great equivocation. Paine called Washington "a sort of non-describable, chameleon-coloured thing called prudence, a substitute for principle and so nearly allied to hypocrisy, that it easily slides into it."

|

|

Statue of Thomas Paine in Paris, France |

Paine lived in penury and his sorry state was finally recognized by the very man he so maligned. In 1784, George Washington sent a letter to James Madison in which Washington sought assistance for this man whose works had meant so much to the creation of the new country. Washington wrote, "Sir, can nothing be done in our Assembly for poor Paine? Must the merits and services of Common Sense [Paine's nickname] continue to glide down the stream of time un-rewarded by this country? His writings certainly have had a powerful effect upon the public mind. Ought they not now then meet an adequate return? He is poor and chagrined if not altogether in despair of relief. New York has done something for him."

In that very year, Paine was given a 300-acre farm confiscated from a Tory by the state of New York. Here amidst a few hogs and cows, Paine returned to Nature, living so frugal an existence that he dried tea leaves to recycle them for further use. Paine wrote another book, which was not well received. It made an impact that was personal but not positive. Titled the Age of Reason and published in 1794, it was a harsh criticism of the Bible and of traditional religion. Paine argued that nature itself was God's only real revelation to humanity. He dismissed Christianity as false, dismissed the Bible as false and condemned many traditional Christian doctrines as fundamentally immoral. This publication was was widely criticized and resulted in Paine's widespread unpopularity. He was shunned by officials and his former fervent supporters in the new republic fell away from him in droves. John Adams said he was "a better hand at pulling down than building."

Despite the wonder of his words and their critcal importance to the revolution, Paine was maligned and mistreated by those he had served so well. He was never revered and unlike other American heroes that included Washington, Franklin, Adams and Jefferson, Paine was not transformed into a Founding Father. Despite having contributed all the monies received for his writings to the revolutionary cause, Paine received no financial assistance when he was destitute. The nation he nurtured ignored his pleas. When he petitioned for financial assistance from the government to which he had given so much, the Committee of Claims replied, "That Mr. Paine rendered great and eminent services to the U.S. during their struggle for liberty and independence cannot be doubted by any person acquainted with his labours in the cause" However, whether or not he deserved compensation for his great contribution to the country, they were not prepared to say and so offered nothing.

Sensing at the age of 72 that his hour glass had been turned for the last time, Paine in 1809 requested a plot in a Quaker church cemetery and was turned down. Unwept, unhonoured and unsung, Paine was buried in a corner of his farm in New Rochelle. Ten years later an English radical named William Cobbett disinterred Paine's casket with the intention of reburying it in England as a symbol of democratic reform. A movement was launched to erect a monument to the man who wrote the Rights of Man, but the plan fell through. Somehow Paine's remains disappeared and were never found.

This bit of doggeral describes the sad fate that found this historic giant whose winged words inspired a revolution.Poor Tom Paine! There he lies:

Nobody laughs and nobody cries.

Where has he gone and how he fares

Nobody knows and nobody cares.

|

|

Statue of Thomas Paine in Morristown, New Jersey |

|

|

Statue of Thomas Paine in New Rochelle, New York |

More than any other public figure of the 18th century, Paine's words from a distant world resound in our world like a trumpet blast. When it shall be in any country that, "My poor are happy, neither ignorance nor distress are found among them, my streets are empty of beggars, the aged are not in want, taxes are not oppressive and rational wonder is my friend, then may that country boast of its constitution and its government." This view of life is a veritable vision to which all modern, enlightened, caring countries should aspire.

[*] Thomas Paine gets his own festival in Lewes, this sometimes home of the massively influential agitator honoured with lectures, debates and folk dancing. Maev Kennedy, guardian.co.uk, Thursday 2 July 2009 |

|

Paine, Thomas |

There's something in the water in Lewes, and probably in the beer as well. The beautiful East Sussex town is stuffed with historic buildings and museums, dear little tea rooms and shops selling flowery dresses and posh chocolates. It looks true blue Tory to its flint foundations: in fact it's been a hotbed of seething anarchy, rebellion, and downright stroppiness since records began.

This weekend, the town begins its first 10-day celebration of one of its most celebrated borrowed sons, Thomas Paine, a lifelong member of the awkward squad. The author of The Rights of Man, which influenced the French revolution, Common Sense which influenced the American revolution, and The Age of Reason which argued against organised religion and outraged anyone he had missed out before, lived in the town for six formative years from 1768.

He lodged over a tobacco shop at Bull House on the main street, now headquarters of the Sussex Archaeological Society and open for the first time for public tours this summer. He married his landlord's daughter (though as with almost everyone he became close to, they soon fell out and separated) and joined with relish in the flourishing intellectual life of the town.

The Lewes spirit Paine found, of debate and furious dissent, will be celebrated in events over the next 10 days.

There will be very serious lectures and seminars on the grandest themes ever to furrow brows: freedom, democracy and the rights of man, organised by bodies such as the wonderfully named Sussex Centre for Intellectual History.

Alcohol also figured in Paine's life, of course, and the festival launches with a Fourth of July Red White and Blue ball on Saturday night, with English, French and American folk dancing, admission just £7 in the town's own currency, Lewes Pounds, £8 for unfortunates from anywhere else. There will be performances of RV Morse's play Only Free Men, previously seen in Brighton and Tehran. The script was sent to Iran as part of an Arts Council scheme, and performed to great acclaim in a Farsi translation last year.

A new mummer's play will be performed in the streets of the town. Written by Mike Turner, it deals not with the doctor, the devil and St George, but with Paine's time in Lewes, including his first major publication, a polemic slightly more specific than the rights of man: the rights of customs officers. Taxmen were no more universally beloved then than now, and The Case of the Officer of Excise was a complete failure.

However, like many of Paine's life's works, the pamphlet refuses to die. During the festival the writer and printer Peter Chasseaud, a leading light of the town's Headstrong Club, descendant of the debating society that Paine joined in the White Hart Inn, will be demonstrating the cheap portable wooden press which made it possible even for impoverished intellectuals to publish and distribute provocative pamphlets. He will be reprinting copies of The Case of the Officer of Excise.

The festival has been created on a shoestring by Paul Myles, a quantity surveyor turned arts entrepreneur and lecturer on child psychology. He has co-authored Thomas Paine in Lewes, a book launching at the festival with a wealth of original research.

Paine died in New York in 1809. Just six people attended his funeral, but his fame has grown steadily since. Lewes glowed with borrowed pride when Barack Obama quoted from Paine's pamphlet The Crisis, which begins with that line borrowed time beyond number by politicians and journalists, "These are the times that try men's souls" in his inaugural address.

Obama has been invited to Bull House and the festival: they haven't heard back yet, but in a town like Lewes you never know.

Copyright © 2013 Website Administrator