foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

RIPE FOR MISCHIEF

History is someone's memories of momentous events..

Throughout history great events have often resulted from trifling causes. A classic example of this is the 13 Colonies where relatively minor grievances led to mighty consequences: two new nations.

In fact, in none of the 13 Colonies had there been an overwhelming passion for independence. In some the advocates of overthrow were actually in the minority. When fifty-six delegates representing 12 colonies (Georgia was not represented) gathered at the first Continental Congress at Carpenter's Hall in Philadelphia on September 10th, 1774, those in attendance were described as being one third Whig,(the up-setters), one third Tory (the stand-patters), and the rest mongrel, (the do-nothings), that is, "those who did not stand up to be counted but worked both sides of the street," cheering whichever side seemed to be winning.

|

|

Carpenter's Hall |

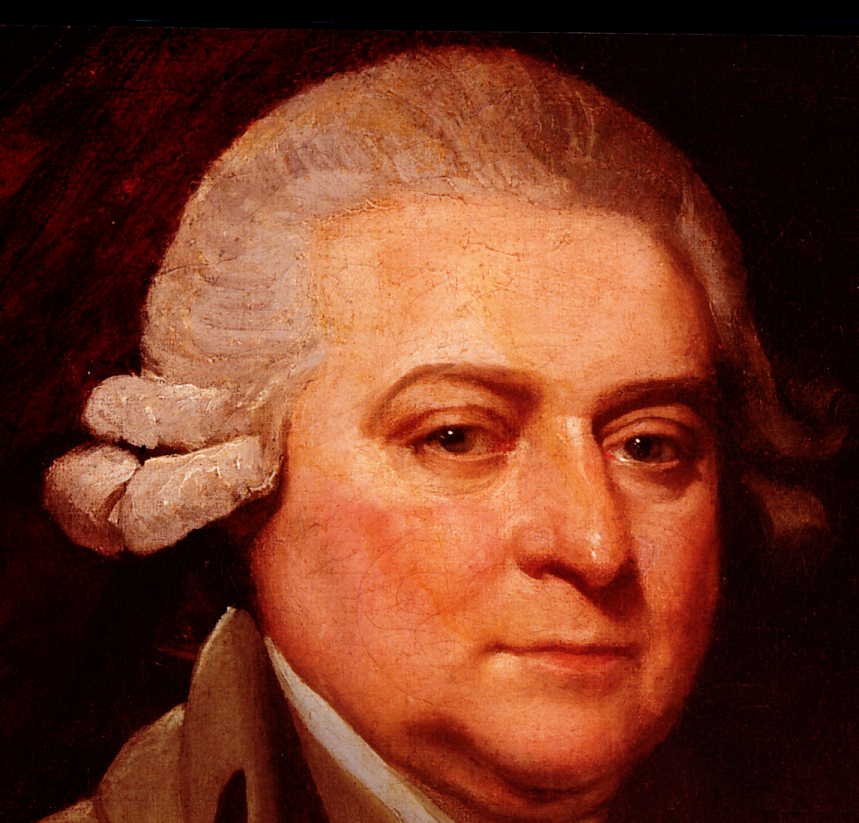

John Adams, one of the most influential and respected of those present, declared: "There is no man among us who would not be happy to see accommodation with Britain." They were largely "champions of national unity," and firm believers in a united British Empire. The patriot cause initially found supporters in all classes and economic groups including those who later became Loyalists. When push finally came to shove, the patriots' position was that of John Adams: "Swim or sink, lie or die, survive or perish with my country is my unalterable determination."

|

|

John Adams |

At the outset of the revolution, perhaps a quarter of the population remained loyal in sentiment to the British throne. More would have declared their support for the crown had they not been intimidated by the "liberty mobs," - the Sons of Liberty or as their victims labelled them, the Sons of Violence. The colonies had a tradition of street brawling that involved mobs motivated by violence and these hordes of hoodlums transformed themselves into the Sons of Liberty or more likely to Loyalists, Sons of Damnation. Gangs that had hitherto contented themselves with baiting and brawling became shock troops for agitators like Samuel Adams. Rival gangs competed for the support of the street.

Americans had to contend with the conundrum indicated by one citizen, Hector St. John de Crevecoeur. " If I attach myself to the mother country, which is three thousand miles from me, I become what is alled an enemy to my own region; if I follow the rest of my countrymen, I become opposed to our ancient masters .... How should I unravel an argument in which reason herself has given way to brutality and bloodshed?"

|

|

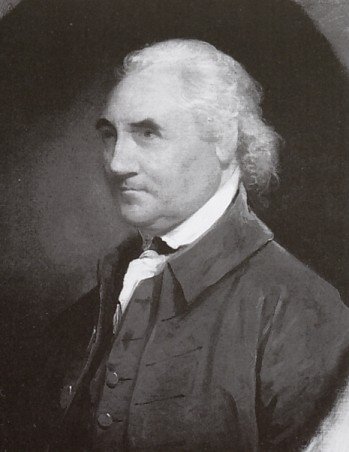

Isaac Barre |

The name Sons of Liberty originated with an Englishman, Isaac Barre, one of parliament's most outspoken members. Barre admonished the British government to "Keep your hands out of the pockets of Americans and they will be obedient subjects." He belaboured fellow members with fiery speeches in support of the Americans. In response to the assertion that the colonies were children planted by a nurturing mother country, Barre, a veteran of the Battle of Quebec, responded that "your oppressions planted them in America. They fled from your Tyranny to a then uncultivated and inhospitable country and yet actuated by Principles of true English liberty they met all those hardships with pleasure." All the mother country did, he railed, was to send officials to spy on them and cause "the blood of those Sons of Liberty to recoil within them."

When word of his speech reached the colonies it was comparable to a cattle prod to the colonists.The name Sons of Liberty caught on and was widely heard throughout the United States. Sons of Liberty chapters sprang up and they pledged to stop by violence any attempt to put the Stamp Act into effect. Before long Sons of Liberty organizations were everywhere. German speaking inhabitants concerned about the mob action were heard to say,"Gegen Demokraten, Helfen nur Soldaten" (Against democrats the only remedy is soldiers.) Rebel crowds converted that to, Gegen soldate, Helfen nur Democraten. (Against soldiers the only remedy is democrats.) The Sons of Liberty included workers of various sorts but they were never the leaders. They were mostly professionals or merchants.

The revolution was propagated at the grass roots level in part through vigilantism and varities of terror. Those who failed to follow fell afoul of local Revolutionary Committees for uttering the wrong words in the wrong places, for not celebrating the right victories enthusiastically enough or in some cases simply because they were disliked by their neighbours. The Sons of Liberty became self-appointed enforcers who appealed to patriotism to justify their barbarous behaviour and lawless rampages. Sons of Liberty, the radical extremists of the Whigs, created the terror which all mobs incite when they overthrow authority and take the law into their own hands. The brutish mobs included rabble from the docks and city slums who bristled with envy and hatred at anyone with wealth. They resented any Loyalists who lived in elegant homes, wore fancy clothes and jewellery or used walking sticks. Little was left to the imagination when these types were loosed on wealthy Loyalists.

Well might Loyalists declare of the Sons of Liberty,

"The Cry was for Liberty-Lord, what a Fuss!

But pray how much liberty left they for us?"

|

|

A Loyalist Terrorized by Sons of Liberty |

|

|

Tarring & Feathering A Loyalist |

Loyalists called these Sons of Liberty "self-constituted committees, conventions and assemblies." With breath-taking suddenness these local committees became lawless mobs, roaming the countryside to intimidate Tories, imposing by fear and force conformity with the wishes of Congress. When silence or support for Congress was not immediately forthcoming from their victims, mobs instantly judged them to be Loyalists and seized their lands along with any possessions they could find. The frightened owners fled for their lives with whatever they could carry.

One Loyalist verse writer ridiculed their attempt at phony respectability.

"From garrets, cellars, rushing through the street,

The new-born statesmen in committee meet."

These roving gangs, the enforcement arm of the movement, struck with frenzied violence. They sought to dignify their dirty work by declaring they were liberty associations and parish committees. All whose only crime was continued loyalty to the government de jure were sifted out by persecution and driven as penniless exiles from their homes by acts of democratic tyranny. Fleeing like the Pilgrim Fathers and the Huguenots before them these proud people helped to create a new country.

|

|

Loyalist Fights Looters |

The Sons of Liberty assembled around what they called liberty trees or poles where they "pledged their fortunes and sacred honours in the cause of liberty." Wherever they discovered that the local government was not actively supporting Congress, they issued semi-official decrees of authority and insolently summoned officials to Liberty Trees to explain their lack of action against Loyalists. The original Liberty Tree was an elm tree growing at the intersection of Washington and Essex Streets in Boston. Sons of Liberty met under its bows until British soldiers dispersed them and converted the tree into 14 cords of firewood.

|

Whenever a mob was needed to stir up enthusiasm or frighten British observers, one could quickly be produced. Wielding broadaxes, these "cudgel crowds" raged around town, wreaking havoc by breaking into magnificent Loyalists' homes to steal, smash and burn what they could not carry or scatter to the winds.While some American officials joined in the public outcry against this destruction, privately they often aided and abetted the brawlers. No one in authority dared to interfere with the mobs, who had a green light to ignore, override or bypass the constraints of legality.

One observer recorded this occurrence.

In His Own Words

"The Loyalist departed a few minutes before the mob entered. They took possession of his house and destroyed, carried away, or cast into the street everything that was in it. Then they demolished every part of it except the walls, even beginning to break away the brickwork. The damage was estimated at 2500 pounds. The town was for the whole night under the awe of this mob. Among the many spectators standing by watching this destruction were magistrates along with field officers of the militia. Nobody dared to oppose or contradict the mob."

This flagrant contempt for the law applied even to the Chief Justice of Massachusetts, who was fearful of attending his brother's funeral because of a chanting mob yelling at his gravesite. In his diary the justice wrote, "Never did cannibals thirst stronger for human blood."

|

They instilled the fear of sudden death into the hearts of lukewarm Loyalists who were the targets of the rebels' vengeful actions. Tories responded sarcastically" "You find these pretended enemies of oppression the most unrelenting of oppressors." Samuel Johnson voiced the same sentiment when he declared, "Why is it that we hear the loudest yelps for liberty from the drivers of negroes?"

A number of able individuals supported efforts to find a middle road between submission and revolution, but they soon discovered they were fighting relentless fate. There was little room for compromise and those who sought to achieve it found only "enmity from both sides and no gratitude from either." With Redcoats at the ready and Minutemen organizing, drilling, and stock-piling arms, a confrontation was inevitable. The American Revolution was the work of a minority of revolutionaries, radicals who were able to convince or coerce an undecided and indecisive majority to support a position from which they could not withdraw later.

Tory supporters - poets, pamphleteers and editors - quickly went on the offensive. They opposed the radical movement and appealed in print to history to halt what they said would go against traditions and cut ancient ties that were inherited from the past. Loyalist leaders admitted there were grievances to be remedied, but they believed relations between the colonies and mother England could be resolved with conciliation and compromise on both sides. Cures, they said, would not come from riot and revolution. Loyalists claimed that the havoc and upheaval sweeping the country were the work of a few crafty individuals, revolutionaries who played on the passions and the ignorance of the mob. Loyalist writers ridiculed these advocates of anarchy.

|

"Here anarchy before a gaping crowd

Proclaims the people's majesty aloud.

The blust'rer, the poltroon, the vile, the weak,

Who fight for Congress, or in Congress speak.

For one lawful ruler, many tyrants we've got,

Who force young and old to their wars to be shot."

Diaries of the time record Tory taunts that were shouted in the heated disputes which took place in taverns, where rebels were given such nicknames as "John Presbyter, Will Democrack, and Nathan Smuggle." Rebels returned the taunts, cursing King George and his underlings.

|

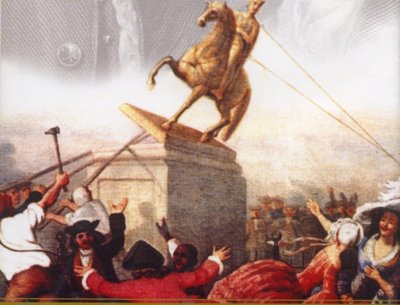

|

Down With George III |

The Congress faced a real dilemma. How could the British principle of parliamentary supremacy be preserved in the face of demands by many for what virtually amounted to self-rule? The first American flag raised by George Washington in 1775 "carried 13 stripes (6 white and 7 red) to mark the union of the colonies, but it still displayed the Union Jack in the canton as a symbol of union with Great Britain." The majority in the colonies wished to preserve local autonomy and at the same time remain loyal to the king. Independence and the birth of a new nation were not part of the original plan.

The Conservatives wished only to assert their rights and this group initially included a large number of businessmen some of whom later developed Loyalist leanings. However, despite the fact that these merchants might prefer king over Congress, it was no easy matter for them to pack up a business and move elsewhere, so for many of them pragmatism, not loyalty won out. When the radicals rejected the supremacy of Parliament and pressed for independence many of the consevative businessmen decided to do what was practical. When independence was declared they supported the rebels, simply opting to go along in order to get along.

Tories severely criticized Washington for his support of the revolution.

"Thou has supported an atrocious cause

Against thy king, thy country and the laws;

Committed perjury, encouraged lies,

Forced conscience, broken the most sacred ties.

Pastures no more hear the lowing kine,

The towns are desolate, all is thine."

George Washington, who became immortal through the magic power of patriotism, was attacked by the Tories as "the head of ragged ranks. Hunger and itch are with him and all the lice of Egypt in the train of this great captain of the western Goths and Huns." There was never anything ragged about Washington, who was always impeccably dressed and delighted in wearing silver buckles, scarlet cloth adorned by gold lace and ruffled shirts. "Whatever goods you send me," he wrote to his London agent, "let them be fashionable." Washington often complained that his clothes fitted him poorly, but this was hardly surprising since he was a big fellow and his tailor was three thousand miles away. During his early service as president, there was widespread public criticism of"Washington's royal manners" and his shameful neglect of the old soldiers. Washington was also criticized for his receptions, which were described as "monarchical parades."

When he toured the new republic set-piece procedures were always followed. Washington rode into each town on his white parade steed, Prescott, with a leopard skin cloth and gold-rimmed saddle accompanied by his dog, Cornwallis. He mounted the horse at the edge of each town in order to make his entrance like that accorded to the heroic mythology surrounding his military career. He appeared, fumed one newspaper, like a canonized American saint, a demigod "perfumed by the incense of addresses."

|

|

George Washington |

It was said that Americans were so deferential to Washington that he might very well have been dubbed St. Washington. However, not everyone saw him as a saint. The belief by some in his presidential infallibility was ridiculed and called a mirage. "Americans had spoiled their president as a too indulgent parent spoils a child." How long would so many "suffer themselves to be awed by one man?" Tom Paine was hightly critical of Washington in one of his letters. For daring to dash so great a personage, Paine's reputation was badly damaged in America. After all it was said, Paine was a mere English commoner while Washington was the Father of his country. One of the Founding Fathers, John Adams, worried that Washington was too much of a god in America.

|

|

Tom Paine |

A military colleague of Washington, General Horatio Gates, who triumphed over Burgoyne at Saratoga, was contemptuous of Washington and questioned the legitimacy of his rank as a general.

|

|

General Horatio Gates |

Washington justified it with the words: "I cannot conceive any more honourable than that which flows from the uncorrupted choice of a brave and free people - the purest source and original fountaiin of all power." Gage's stunning victory did result in a whispering campaign against Washington that had simmered just below the surface ever since the debacle at Fort Washington where General Howe defeated an American force under Washington. However, criticism of Washington took the form of whispers because of his peerless status as His Excellency which raised him above all political squabbles.

. The Federalists considered the wooden-toothed president as sacred, seeing Washington as a crtically important hero without whom the republic would not survive. It was all part of the "mythic tale of our nation's founding." The president had become an iconic figure in the United States, the embodiment of the public's values. Thus began the insatiable appetite among Americans for information about their president who was expected to be "an uncommon common man," of the people but not like them. John Adams disagreed with this glorification and suggested that "we allow a certain citizen (i.e. Washington) to be wise, virtuous and good without thinking of him as a Diety or savior." Writers were told to provide a portrait of the man, not a marble statue.

While there never seemed to be any shortage of those willing to serve as Sons of Liberty, the availability of soldiers to look down the gun barrel of a British Redcoat was another matter. There were only a handful of patriots ready to hang together or separately. Despite the existence of a large reservoir of men of fighting age, Americans never really rallied enthusiastically to revolutionary recruiting posters such as this one.

"Wanted: All Brave, Healthy, Able Bodied and Well Disposed Young Men to serve under General Washington in the defence of the Liberties and Independence of the United States. Their reward will be a truly liberal and generous bounty of Twelve dollars plus the opportunity to spend a few happy years in viewing the different parts of this beautiful continent and returning with pockets full of money and a head covered with laurels."

The popular image of patriots flocking to fight the British never did reflect reality. Inflamed by passions and stirred by patriotism, men will "fly hastily and cheerfully to arms." But soldiers will not serve on selflessly come what may once the first emotions have subsided. Year after year Washington's regiments were at least one-third below their required numbers and the availability of sufficient officers also posed problems. "Love of country," wrote Washington, "and belief in the cause were noble sentiments, but even among officers, those who acted upon principles of disinterestedness were no more than a drop in the bucket." He was contemptuous of the militia.

"To place any dependence on militia is assuredly resting on a broken staff. Men just dragged from the tender scenes of domestic life unaccustomed to the din of arms totally unacquainted with every kind of military skill which being followed by a want of confidence in themselves when opposed by troops regularly trained, disciplined and appointed, superior in knowledge and superior in arms makes them timid and ready to fly at their own shadows."

Among Washington's warriors who did don the uniform, their behaviour left a great deal to be desired. Stealing was rampant and Washington demanded harsher punishments in order to check the "lust for plunder and widespread drunkenness." He was authorized by Congress to offer new recruits 20 acre parcels of land and the number of lashes for drunkenness and neglect of duty was increased from 23 to 100. Mutiny and desertion also plagued Washington's forces and he petitioned Congress to permit flogging sentences of 500 lashes. Americans, said the British, were becoming "bloodybacks" too. In addition to the shortage of soldiers, equipment, weaponry and financing were difficult to come by.

British officers with their aristocratic, autocratic background initially displayed contempt for their backwoods adversary. They considered the colonial foe their social inferiors and this haughty, condescending attitude created greater resentment among the rebels, their infuriated anger turning to loathing of the British for their arrogance. Contempt was mutual for early on Yankee backwoodsmen had lost their dread of the redcoats. Ben Franklin said the patriots had never been in awe of the British regulars for they had taken note of their defeat Britain's General Braddock in 1755.

In Franklin's Own Words

"This gave us the first suspicion that our exalted ideas of the prowess of British redcoats had not been well founded."

Despite Franklin's bravado, there was every expectation that Britain, the mighty 'Goliath', would quickly quiet the anorexic David. But Britain's armed forces were not in 1775 what they had been in 1759 when it seemed nothing could stand against them. By 1775 the whole world was against 'Goliath' - France, Spain, the Dutch - thus the conflict spread to other continents and all became fair game and fighting provided fresh sites for death and defeat.

|

|

Benjamin Franklin |

|

British derision and disdain of the American military changed to grudging respect when it was discovered American soldiers could fight effectively and successfully, both in hit-and-run raids and stand-and-fight battles. The American army's ability to bounce back after suffering a defeat kept the revolutionary cause alive.

In the early stages of the American Revolution, British civil and military officials fully expected that the majority of American colonists would rise up and overwhelm their few, misguided, rebel countrymen. It was never doubted that supporters of the sovereign would easily overcome the asinine revolutionaries described by one British general as "a few artful folks" whose folly and foolish talk of liberty and democracy would soon be settled by the British regulars. British officers talked of triumph before the fighting had even begun. Loyalist Americans, the other side of the rebel coin, were also certain their sovereign would quickly subdue the rebel's ragtag army. Loyalist complacency in the early stages of the revolution was no match, however, for rebel dedication and desperation. Even in colonies where support for the sovereign was strongest like New York and the Carolinas, the Loyalist cause was a losing one and Loyalists never really understood why this was so.

Not only did the British military fail to win over the hearts and minds of Americans, they mishandled completely the Loyalist element of the population. Neither Loyalists nor Native warriors proved crucial factors in the conduct of the war simply because they were never used effectively by the British to crush colonial resistance. As one historian observed, "The British were never fully clear as to what the Loyalists' role should be and accordingly the Tories were alternately ignored or courted." With supportive leadership from British officers in the early stages, Loyalists might well have thrown off the tyranny of the new Congress. If the British military had made serious efforts to protect, organize and train Loyalists at the start of the struggle, the outcome might have been different. But they failed from the first to make the most of the force that was theirs for the asking.

Initially, large numbers of Loyalists were anxious and able to fight but they were given little opportunity to do so. There were few military commands to join and minimal effort was expended by the British military to recruit them into organized fighting forces of their own. They were not even offered commissions in the regular army. Colonials were treated largely with indifference and in some cases scorn by British officers who were skeptical of the fighting effectiveness of armed civilians. The Loyalists who did fight had difficulty getting adequate equipment. Capable, clever Loyalists who would have been especially useful because they knew the ways of the country were ignored, while "coxcombs, fools and blackguards" of the regular service received every favour.

Britain's small military establishment compelled Britain to enlist support from other quarters. Faced with a poor enlistment rate for what many considered an unpopular war, Britain chose to bolster its fighting forces with hired killers - German mercenaries. The British government paid outrageous rates for the "hireling sword" from Hesse and Hanover.

|

However, their commitment to the cause lacked the passion and the patriotism of the beleaguered Loyalists. In fact, the brutish behaviour of some of the blue-coated "German boors and rascals" stirred enduring resentment in the colonies. Dressed in the cumbersome German uniform of the time with heavy sabres, huge head gear and great boots that came up to the thighs - outlandish equipment for warfare in America - the Hessians became much-hated by Americans who came in contact with them.

|

|

Cartoon of Hessian Soldier |

British commanders and politicians were never able to make up their minds whether to seek to conciliate the rebels and go softly with them or let loose the dogs of war against them as they would against any other country. "No greater mistake - and there were many mistakes - was made by English ministers in their conduct of the war than their excessive reliance upon a split in American ranks and upon active, large-scale aid from the Loyalists." When the British military finally discovered that the much-maligned American soldiers could fight, they belatedly sought support from the Loyalists and expected it to materialize on command. They had, however, turned to them too late. When large numbers of Loyalists failed to respond immediately to this latter-day call to the colours, British officers became embittered and resentful and their correspondence reflected rancour and recrimination.

General Clinton was assured that thousands of Loyalists were eager to join him, but he was soon to be profoundly disappointed.In His Own Words

"It is clear to me that there does not exist a number of friends of the Government [the Loyalists] sufficient to defend themselves when the troops are withdrawn."

|

|

General Henry Clinton |

Another incensed general was even more skeptical. "Fatal infatuation!" cried General O'Hara

|

, "When will the Government see these Loyalists through the proper medium? I am persuaded never." Despite Lord Cornwallis's generally more favourable attitude towards the Loyalists, he too was brutally blunt in his criticism of their contributions. "Our Loyalists friends hereabouts are so timid and stupid as to be useless."

|

|

General Lord Charles Cornwallis |

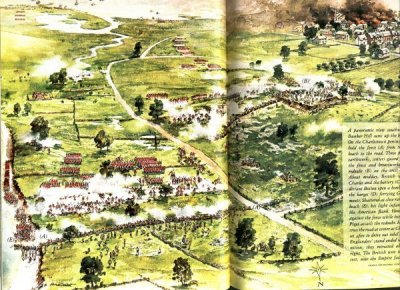

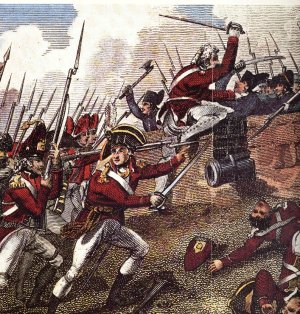

It was not the Loyalists who lacked intelligence. If the British commander at the Battle of Breed's (Bunker) Hill had taken the advice of the Loyalist leaders, that fiasco resulting in the tragic loss of so many red-coated regulars could have been prevented. Instead General Thomas Gage fed them into a cauldron of fire and they won the hill at fearful cost. The number of British dead exceeded more than 30 per cent of those engaged making it

|

|

General Thomas Gage |

one of the bloodiest battles known to history. British casualties from 3500 men totalled 1054. American losses equalled 100 dead and 267 wounded. The battle lasted an hour and a half.

|

|

Bunker Hill Panorama |

|

|

Charge at Bunker Hill |

|

|

Breed's Hill: Britain's Pyrrhic Victory |

In another case the early successes of British general John Burgoyne were due in no small measure to his wise use of Loyalist auxiliaries such as Butler's Rangers of New York. If the British had supplied the Loyalists with effective leadership Britain might never have lost its first empire. Mismanagement and muddling on the part of the British was an important element in determining the outcome of the war.

On the other hand some argued that the British placed "a naive and fantastic reliance on the Loyalists." While there were Loyalists who criticized British officers, particularly Howe and Clinton, for not supporting and making vigorous use of them, there were others who complained about the Loyalists' lassitude. "Howe is as much deceived by you [Loyalists] as the American cause is injured by you. He expects you will all take up arms and flock to his standard with muskets on your shoulders. Your opinions are of no use to him unless you support him personally for 'tis soldiers and not tories that he wants."

According to another argument Britain faced a fatal dilemma. Committing fully to the Loyalists would have meant pushing civil war to the extremes and seeking to obliterate the rebels. While many horrors and atrocities did occur, the behaviour of the British army was considered mild compared to its conduct in European wars. The country was not systematically ravaged because the British cause was not to utterly crush the Americans, it was to defeat the American army and conciliate the population. Turning the Loyalists loose on their brethren would have meant all-out savage warfare and considerably less likelihood of conciliation. This presupposes foolishly that Loyalists would have lost control of themselves and run amok among their brethren slaying all in their path.

The American triumph at Saratoga was a major turning point because this victory convinced the French that perhaps the ragtag rebels might just have a chance of actually defeating mother England. Anxious to be in on the kill if this occurred, the French decided to join the fray. With the help of French finances and French naval and military might, the Americans eventually prevailed. Before their independence was achieved, however, a savage war raged between rebel and royalist, a war more brutal and vicious by virtue of the fact that the Loyalists and the patriots pitted against them were often former friends or even members of the same families.

This rebel rhyme said it all.

Tories with their brats and wives,

Should flee to save their wretched lives.

Copyright © 2013 Website Administrator