foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

BENEDICT ARNOLD & HIS FOIL, JOHN ANDRE

History promises no final truths.

Benedict Arnold is to most Americans a fiend most foul, a dastardly traitor. However, Arnold might very well have become one of the great heroes of the American Revolution for his valor and vision were critical to the American victory at Saratoga, New York. In fact, one American historian, George Neumann, has written that "without Benedict Arnold in the first three years of the war, we would probably have lost the Revolution."

|

|

Benedict Arnold leading the charge at Saratoga. |

Instead, the name of this turncoat who save America is synonymous with villianous treachery for he almost succeeded in delivering West Point and Washington himself into the hands of the British.

|

|

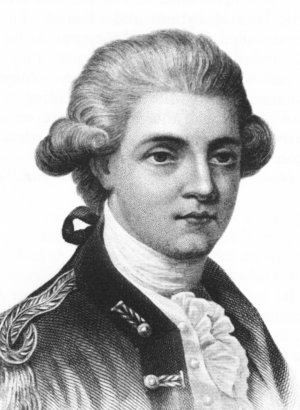

Benedict Arnold |

Arnold was born in Norwich, Connecticut on January 14th 1741, a sixth generation New Englander. He was tall for his time, five foot nine and powerfully built. He was strikingly handsome, had a ready smile, a dark complexion, a distinctive nose, a prominent chin and intense, piercing blue eyes that could quickly turn from cordial to cold. The name 'Arnold' was highly esteemed, and had long been respected throughout the 13 Colonies. The fifth Arnold to bear the name, Benedict continued the Arnold tradition of meritorious service to his country. He was an excellent rider, a dead shot, a fair sailor and the captain of a crack militia unit. He was also vain, bright and inventive. During the American Revolution Major General Arnold was a bold, fearless, daring army commander, the "fire and sword" of the American effort at the second battle of Saratoga. Arnold once said that "his courage was acquired and that he was a coward till he was 15 year of age."

In December 1775 in a futile American assault on Quebec, Arnold was shot in the leg below the knee. He was carried out of the line of fire by his fervent followers in whom he inspired love and loyalty. On another occasion in defiance of orders to remain where he was, Arnold displayed his fiery temperament and military mastery by leading three regiments into battle like an avenging scourge. In 1777 Benedict Arnold is credited with contributing greatly to the defeat of Lieutenant General John Burgoyne at the tide-turning 2nd Battle of Saratoga.

Burgoyne, who had boasted his redcoats would rout the "Rabble in Arms," was forced to eat his words and to declare abjectly to his conqueror, General Horato Gates, "The caprice of war has made me your prisoner." Because of this strategic American victory the French government decided that the 13 Colonies might very well be able to defeat the best of British manhood. As a result France, the only country with a navy capable of challenging the British fleet, committed money and men to America's cause. This support made possible America's ultimate victory over Great Britain. Arnold, who was wounded a second time in the same leg, whispered hoarsely, "I wish it had been my heart."

Known as the 'Fox,' Arnold was impulsive, stubborn, sensitive and proud. He was also clever, fast and elusive and always ensured he was familiar with the terrain on which he was going to fight. He had great stamina and struck fast when least expected. The French called him "the Hannibal of the North" Desperate for fame and fortune, Benedict stopped at nothing to further his own interests. He agonized over any real or imagined insult to his character, brooding until he could avenge the slight in some way which he did on one occasion by fighting a duel. His motto was Sibi Totique - For Himself and for Everybody.

Whatever the personal faults of the stocky, handsome, braggart, Arnold was acknowledged during the revolutionary war by British and American leaders - he did after all serve both sides - to be a general of the highest calibre. He had a messianic following among soldiers, whom he led, never followed, shouting over his shoulder with his powerful voice as they advanced into battle, "Come on boys."

|

General George Washington held Arnold in the highest esteem and might have said of him as Lincoln said of Ulysses S. Grant during the American Civil War, "He fights." Arnold was the kind of officer who made a difference. His tactics like his martial prose were clear and direct - a swift counterattack.

Arnold loved luxury and was perpetually short of the kind of money he needed to indulge his extravagant lifestyle. Because he was not fully recovered from injuries received at Saratoga, Washington appointed him military governor of Philadelphia where he enjoyed a lavish lifestyle, living well beyond his means and revelling in the town's social life. He rode about in a splendid carriage with liveried attendants, employing troops as servants and labourers and spending money he did not have on horses and house-parties at Mount Pleasant, his large home on the Schuylkill where he entertained guests with known loyalist leanings. He married an exceptionally attractive nineteen-year-old named Margaret Shippen, his second wife. Some attribute his treason to greed, while others say Arnold succumbed to the blandishments of his beautiful Tory wife from a prominent Loyalist family.

|

|

Only authentic portrait of Benedict Arnold drawn in Philadelphia when Arnold was military governor. |

Arnold was reprimanded for abusing his authority and using his office for private gain. A court-martial was held on four charges. He was acquitted of two of the four charges and the other two were sustained in part. He was censured by President Washington but received no more formal punishment. Arnold's pride was shattered by a blow from which he never completely recovered. His ambition, pride and hot temper made him many enemies some of whom were members of the Continental Congress. In February 1777 Congress promoted five brigadier generals to major generals not including Arnold despite him being number one in line for promotion. All were inferior to Arnold in seniority, experience and ability. After protests he eventually received his promotion but his seniority was not restored. News that Arnold had been ignored and humilitated infuriated Washington who had not been consulted.

By dint of Arnold's persevering solicitation and his former valuable services, Washington assigned him to command the garrison at West Point on the Hudson River, "the Rockyest Mountainest Place" he had ever seen. Washington regarded the fortress as the lynchpin of the Hudson corridor and a most strategic location.

Arnold never forgot nor forgave and still embittered by criticism he thought was undeserved and enraged by the lack of recognition for his military genius, he became obsessed by a passion to avenge his shattered pride. What better way to seek revenge than by betraying those who had betrayed him. He decided to offer his services and West Point to the British.

Arnold's defection rocked the rebels to the core. "Treason, treason, treason!" wrote Washington's chief of intelligence. "We are all astonishment - each peeping at his next neighbour to see if any treason was hanging about him." It was shattering to learn that America's most gifted combat leader had become a spy for the British. His vainglory and vengeful nature had converted his fighting fame into instant infamy and he was burned in effigy throughout the colonies. Said the devastated Washington, "Arnold wanted feeling and was so hackneyed in villainy that he lost all sense of honour and shame." He vowed to avenge Arnold's treachery and issued secret orders authorizing the assassination of the general he had so admired.

Washington, who had considered Arnold one of his most effective officers, had said of him, "His presence will be of infinite service." This was certainly was true as far as the British were concerned, for by the end of 1780 Arnold had donned the scarlet coat and become commander of a British force in the heart of Virginia.

|

Arnold defended his defection by ascribing his actions to principle, claiming he had changed his mind about rebelling against his sovereign. "Well I think I have made a mistake," To assuage his guilt he claimed that he detected a cooling off of America's ardor for war and said he perceived a willingness in the colonies to come to some sort of negotiated settlement with Britain. While this was treasonous talk, in point of fact every American revolting against King George III was committing treason. Arnold simply did it twice.

Negotiations for the British capture of the American bastion of West Point were carried on by John Andre, the aide-de-camp and spy chief of General Sir Henry Clinton, commander-in-chief of the withdrawal from Philadelphis. Arnold was to be paid 20,000 pounds for the fort and if he failed to deliver the fortress, 10,000 pounds. This substantial bribe was to "create the most notorious traitor in American history."

In British correspondence at the time, Arnold was referred to as 'Monk,' a reference British officers immediately understood for Monk was a Scottish general who had betrayed the British army. The secret service aided by Loyalist sentiment played a key role in the revolution. Invisible ink, notes left in trees and in hollow bullets and templates made to fit over coded letters were some of the devices used by spies to transmit secret information. Spies were everywhere. All commanders relied on them and the intelligence they received just before battle concerning the latest reports on the enemy's strength and location.

Arnold was a traitor. John Andre, Arnold's foil, was a spy. Andre, who used the fictitious name, John Anderson, was multi-lingual, a keen artist and a keeper of diaries. Like many British officers he was a devotee of amateur theatricals. With his good-looks and easy manner, he enchanted men as well as women.

|

|

Major John Andre |

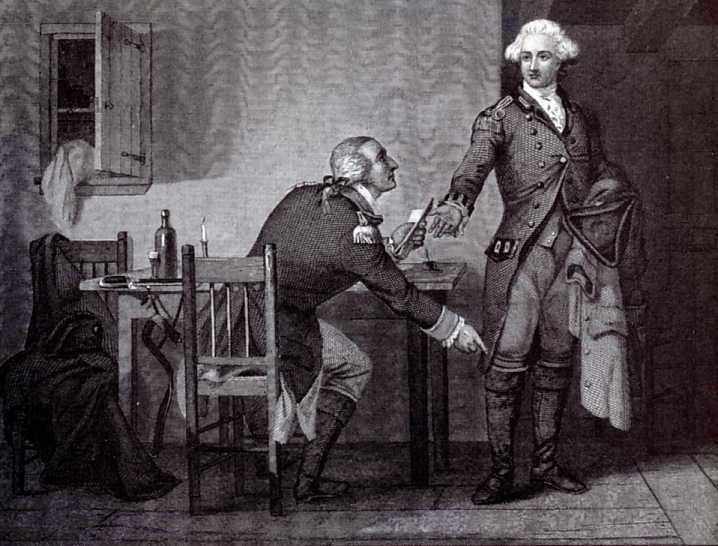

Andre resplendent in his scarlet uniform, walked up the gangplank of Royal Navy sloop-of-war Vulture and sailed up the Hudson River to learn all he could about West Point's defences preparatory to an attack on it by British forces. On the night of September 21, he came ashore from the "Vulture" anchored in the Hudson just south of West Point. He met with Arnold, accepted a sheaf of documents outlining the state of the garrison and the arrangements which had been made for its defence. Andre spent the night at the house of Joshua Hett Smith some miles within the American lines. He knew it was dangerous but it was too late to go back. He heard a cannonade in the direction of the Vulture The ship, under fire from American batteries, was forced to drop downriver as a result of which Andre had to cross overland through American-held territory.

|

|

Arch Conspirators: Benedict Arnold and John Andre |

On Saturday morning Andre removed the gold-embroidered uniform of senior British officer and donned a plain, crimson great-coat lent him by Smith, a loyalist collaborator. Stuffing Arnold's secret instructions into his white, silk stockings, he set off to find a road back to New York and his headquarters.

Chance played a central role in his revelation. It was pure fate that on his way he encountered three 'bushmen' in patriot dress, if, in fact, they were patriots. The three stopped the passing traveller in New York's uneasy neutral territory. Like other skinners they were not out for glory or cause but booty. All who passed their way were fair game for plunder. If Andre had had any money on him at the time, he might very well have passed on to Clinton's headquarters with all the papers on his person and Arnold's pass in his pockets. The three highwaymen were more interested in lucre than liberty and would have freed him for cold, hard cash.

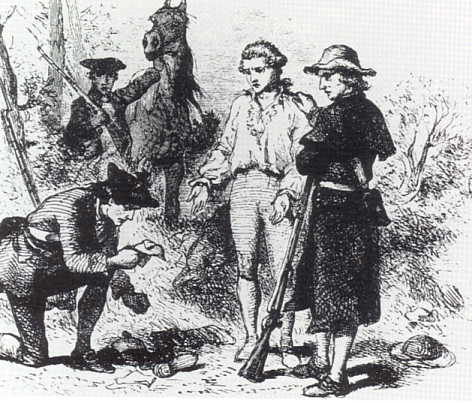

Andre greeted them with the ill-advised query, "Of what party are you?" They cleverly replied, "Yours." Andre relaxed and told them he was with the British army. With these words he placed the noose about his own neck. They searched him, discovered the incriminating documents in his boots and the signed pass given him by Arnold. The incriminating papers were send to Washington who ordered a Court of Inquiry.

|

|

John Andre Undone |

|

|

Frisked and found flatfooted with the goods. |

|

|

Damaging Documents from Benedict in the Boots of Major Andre |

|

|

Caught by militiamen with materials from Benedict Arnold |

The Court before which Andre was arraigned and examined consisted of fourteen general officers. Andre was convicted of spying and sentenced to death by hanging. Washington approved the sentence and ordered that it take place the next day at 12 noon. Major John André became one of the most famous prisoners of the Revolutionary War. A favourite of General Clinton, the handsome young major was also popular with the "high society" of Philadelphia which the British occupied until June 1778. Intelligent and witty, he was noted for the elaborate entertainments he wrote and designed for parties. Appeals were made for his life from friend and foe alike but the sentence stood.

|

|

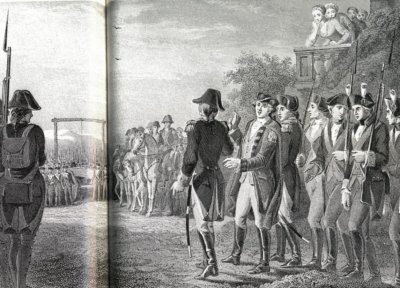

Trial of Major John Andre |

When Lieutenant Colonel John Graves Simcoe, a good friend of Andre, learned of his detention, Simcoe offered to attempt to rescue him with a corps of Queen's Rangers. The offer was not approved. It was believed at the time that General Clinton had offered to exchange American prisoners for Andre, but Simcoe said no such offer was ever made. Amongst papers found pertaining to this incident was a note supposedly in the hand-writing of Hamilton, Washington's secretary. It stated: "The only way to save Andre was to give up Arnold." There was disbelief and disgust in England over the execution of Andre who it was believed should not have been executed as a spy.

Andre was to be hanged at Tappan near the boundary between New York and New Jersey. He petitioned Washington to "adapt the mode of death to the feelings of a man of honour" and allow him to die like a soldier. Washington refused his request to be shot. In a last letter to a friend, Andre confided, "I could not think an attempt to put down a civil war a crime." One of his visitors, Washingon's chief of intelligence, Colonel Webb, exclaimed, "By heavens I never saw a man whom I so sincerely pitied. He seemed to be as cheerful as if he were going to an assembly." The day before his execution on 2nd October 1780, he sketched himself at a writing desk.

|

|

John Andre's sketch of himself the day before he was hanged. |

On his last day Andre cheerfully consumed the breakfast which Washington had sent him from his own table. Dressed in his regimentals and boots, he walked to his execution arm in arm with two young American officers who had become his friends, bowing as he passed the senior officers who had sentenced him to hang. The sight of the scaffold and rope he turned sharply, stumbled and looked down for a moment but quickly reovered his composure. Asked why this unexpected show of emotion, he replied, "I am reconciled to my death, but I detest the mode."

|

|

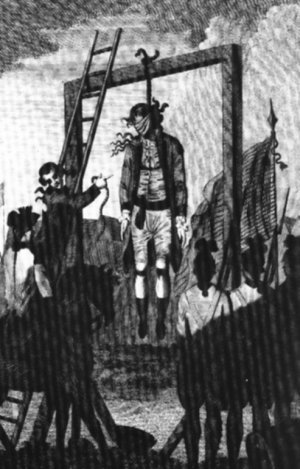

Turning sharply at the sight of the gallows he said, "I detest the mode." (11) |

The sound of the drums, Andre said, as he climbed onto the cart that transported him to kingdom come, was more musical than he had imaginged. He waved off the executioner and opened his shirt collar, slipped the noose over his head and securely placed the knot under his chin. He then tied a silk handkerchief over his eyes. When asked if he wished to make a statement, he said simply, " I pray you bear me witness that I meet my fate like a brave man." While awaiting the drop he was heard to murmur, "It will be but a momentary pang." When the wagon on which he stood was withdrawn he fell and was brought up sharply.

|

|

The Execution of Major John Andre |

A large crowd attended the execution and five hundred soldiers held back the throng of men, women and children who wept and moaned as they watched his body sway for a full half hour before it was still. All were impressed by his fortitude and bearing in the face of his fate. Even American soldiers regretted that he had to die the death of a traitor. His remains were placed in an ordinary coffin and interred at the foot of the gallows, the spot consecrated "by the tears of hundreds." Thus died the accomplished Major Andre in the bloom of life, the pride of the royal army, the valued friend of Sir Henry Clinton and the hero of all England. When Washington announced his death to Congress, he said he had met his fate like a brave man.

|

|

Self-portrait of John Andre |

The Ballad of Major Andre was written soon after his death. Sung to the tune 'Bonny Boy' it contained eleven verses two of which follow.

"Andre was executed, he look'd both meek and mild;Around on the spectators most pleasantly he smiled;

It moved each eye to pity, and every heart there bled,

And everyone wished him releas'd and Arnold hung instead. He was man of honour, in Britain he was born,

To die upon the gallows most highly he did scorn;

And now his life has reached its end, so young and blooming still,

In Tappan's quiet countryside, he sleeps upon the hill."

The remains of Major JOHN ANDRÉ were on the 10th of August 1821, removed from his grave in Tappan, New York, by JAMES BUCHANAN ESQr His Majesty's Consul at New York, Andre's skull had come apart from his fractured neck-joints and a nearby peach tree, whose roots had wound themselves around it "like a net," had to be destroyed in order to release the skull. His remains were transported back to England for burial near his monument in the nave of the hallowed Hall of British Heroes - Westminster Abby. Under instructions from His Royal Highness The DUKE of YORK and with the permission of the Dean and Chapter, he was finally deposited in a Grave contiguous to this Monument on the 28th of November 1821.

|

|

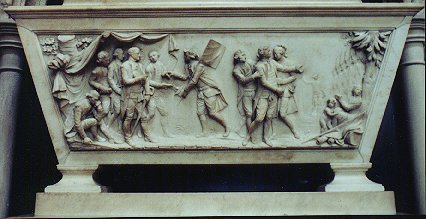

Monument to John Andre in Westminster Abby |

The monument of Major John André, executed as a spy by the Americans in 1780, was designed by Robert Adam and carried out by Peter Mathias Van Gelder. Erected at the expense of King George III, it shows a mourning figure of Britannia with a lion, seated on the top of a sarcophagus lamenting the fate of Andre. On the front of this is a relief showing George Washington in a tent receiving a petition and Major André being led away to execution.

. |

|

Sarcophagus of Monument to John Andre |

On the sarcophagus is a representation of Washington and his officers in his tent at the moment when he received the report of the court of inquiry; at the same time a messenger has arrived with the letter of André to Washington asking for a soldier's death. On the right is a guard of Continental soldiers, and a tree on which André was executed. Two men are preparing the prisoner for execution, while at the foot of the tree sit Mercy and Innocence.

The inscription reads: SACRED to the MEMORY of MAJOR JOHN ANDRÉ, who raised by his Merit at an early period of Life to the rank of Adjutant General of the British Forces in America, and employed in an important but hazardous Enterprise, fell a Sacrifice to his Zeal for his King and Country on the 2nd of October AD 1780 Aged 29, universally Beloved and esteemed by the Army in which he served and lamented even by his FOES. His gracious Sovereign KING GEORGE the Third has caused this Monument to be erected.

Meanwhile Benedict Arnold's plot to betray his country was discovered and the rogue barely escaped capture by fleeing on the British frigate Vulture, an exploit Thomas Paine described as "one vulture receiving another." In return for his defection, Arnold was awarded the rank of a British brigadier general. At his own request, he was authorized to raise a Loyalist battalion in which his three sons received commissions as lieutenants. During the war they received salaries and afterwards were given lifelong, half-pay pensions. Arnold was paid the equivalent in today's currency of $200,000 together with a pension, the two totalling something over $400,000.

Benedict Arnold, a pre-eminent traitor, was rewarded by Great Britain for his contributions to the cause of the Crown. Part of the payment for his perfidy involved a grant of land in Canada where he planned and carried out a nightmare march in an unsuccessful attempt to capture the country the Continental Congress hoped would become "the 14th American state." The grant of land was located deep in the heart of Ontario. As a half-pay officer of a Loyalist regiment, he was entitled to apply for Crown lands and he did so early in 1794. When he and his sons petitioned for land in Upper Canada, their applications were set aside until they could decide whether they intended to reside within the colony, a basic condition of any land grant. Two of his sons did become settlers in Upper Canada, but Arnold disdained residency in the rough. He had no intentions, he said, of venturing into "that inhospitable wilderness." [**] Nevertheless, Arnold pressed for payment in land for past services and sacrifices "in support of the Government."

In 1797 Arnold applied for a grant to his family of 50,000 acres. When told this was excessive he revised his request the following year to 5,000 acres for himself and 1200 each for his wife, his sister and his five sons.The British government was undecided as to whether or not to grant his request and turned for advice to Upper Canada's first lieutenant-governor, John Graves Simcoe. Simcoe had known Arnold as enemy and ally during the revolution and held him in the hightest contempt. Simoce's response was that Arnold was "a character extremely obnoxious to the original Loyalists of America," and cautioned that granting land to a non-resident would create a dangerous precedent. However, Arnold had powerful interests in England. When Brigadier General Arnold of the British army made his first appearance at the court in London, he was "ushered into the Royal presence on the arm of Sir Guy Carleton," ironically the very man who defeated Arnold when he attacked Quebec with troops that according to Washington, "came not to plunder but to protect." Arnold's amiable enterprise culminated disastrously on New Year's Eve. in the icy wilderness outside Quebec.

|

|

Sir Guy Carleton |

Arnold received his petition on the 29th of October 1799, a land grant of 13,400 acres "on the usual terms and conditions, that of residence alone excepted." The land allowance granted by an order in council was made "in consequence of Arnold's late gallant and meritorious services." Not only was Simcoe's advice not taken, insult was added to injury when Arnold was granted land in York county's townships of Gwillimbury East and Gwillimbury North, the name Gwillim being Mrs. Simcoe's maiden name. After Arnold's death monies from the sale of these properties were used by his widow to pay off Arnold's considerable debts.

|

|

Mrs. Benedict Arnold and Son, Edward Shippen Arnold |

Considered the greatest, most notorious of all the loyalists, Benedict Arnold sailed for England in 1783 never to return to the States. Arnold's last years were miserable for his health was broken by frustration and rage, as well as by gout and dropsy. Shortly after his 60th birthday at 6:30 a.m. on Sunday, June 14, 1801, he died "without a groan," unwept, unhonoured and unsung. Britain welcomed the defection but not the defector and Arnold was buried without military honours in a crypt in the small copper-spired Church of St. Mary's in London. A century later during renovations to the church, it was said that Arnold's body was disinterred and accidently reburied with hundreds of others in an unmarked grave. Undoubtedly, the British government was more than grateful that no monument, no marker, nothing in Britain bears the name of this infamous traitor.

Had Arnold died during the battle of Saratoga he would have gone down in history as one of America's most celebrated soldiers.

|

|

Arnold at Battle of Bemis Heights |

Instead he lived and became that country's most detested traitor. The American dichotomy of feeling for Benedict Arnold, hero, patriot and traitor, was best expressed by an American officer whom Arnold captured. "What would be my fate, if I should be taken prisoner by the Americans?" the former patriot asked. The officer is supposed to have replied,

In His Own Words,

"They will cut off that leg of yours wounded at Quebec and Saratoga and bury it with all the honors of war. Then they will hang the rest of you on a gallows!" There is, in fact, a statue honouring the leg of Benedict Arnold. On Bemis Heights battlefield at Saratoga.

"To the most brilliant soldier in the Continental Army, an unbalanced personality."

|

Whatever Benedict Arnold's strengths were and he had many, he retains in the popular mind of America the epithet of "villain most foul."

"The evil that men do lives after them, The good is oft' interred with their bones."[*] Died This Day, Benedict Arnold, Globe & Mail, June 20, 2006

Soldier born at Norwich Conn. on Jan 14, 1741 or 1742. After being apprenticed to an apothecary, he preferred the excitement of military life and joined a New York militia during the Seven Years War and fought for the British Army against France. When the U.S. War of Independence erupted, he switched sides, formed a small army of militia and took Fort Ticonderoga. Promoted to General, he was part of a disastrous, ill-planned invasion of Canada but distinguished himself through acts of cunning and bravery. The revolutionary cause began to lose its appeal when the Continental Congress voted to join an alliance with France, which he hated. In the previous war, he had suffered at the hands of the French. He was passed over for promotion and also felt wrongly accused of corruption. Put in charge of the garrison at West Point, N.Y., he planned to turn the fort over to the British but the plot was exposed and he fled to England. He was rewarded with 6,315 Br Pounds and a pension. In 1786, he settled in Saint John. He remained only five years and left under a cloud. In 1798 he was awarded a large grant of land in Upper Canada but never again left England.

[*] While Benedict Arnold, the famous Revolutionary War General, never came to Canada, his granddaughter did. Margaret McEwan of Windsor was awarded a gold watch for her kindness in aiding German travellers on the Great Western Railway who suffered from the cholera epidemic of July 1854. She is buried at St. John’s Cemetery, Sandwich. ["Loyalist Trails" UELAC Newsletter 2007-21 May 27, 2007]

Copyright © 2013 Website Administrator