foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

THE DUKE'S DIARY

History holds a mirror up to the dusty documents of the past.

The Aboriginals gave John Graves Simcoe the name Deyonguhokrawen meaning "One whose door is always open." It is said he never refused an audience to anyone. According to the chief justice, William Osgoode, Simcoe had "a benevolent heart without much discrimination." His manner "was simple, plain and obliging," which was not a bad qualification for a post in which friendly personal relations were of real importance. Simcoe did bristle with animosities but these were usually directed towards people at a distance and generally toward his superiors.

Among the numerous guests who shared the Simcoes' hospitality during their sojourn in Upper Canada none was more observant of the Simcoes, the province's people or its various communities than the Duc de La Rochefoucauld-Liancourt, a French nobleman. A confidant of the ill-fated Louis XVI, the Duke was forced to flee France following the decapitation of his king. After residing in England for a time the Duke sailed to North America to begin a tour of the United States and Upper Canada. He entered the province at Fort Erie on June 20th, 1795. Two days later he and his five companions were greeted at Newark by Lieutenant-Governor Simcoe.

The Governor had been forewarned of the duke's visit by the British ambassador to the United States who requested that he be shown every consideration. A personal passport was prepared for him which directed commanders of all British posts in the province "to suffer the bearer to prosecute his journey without hindrance or molestation." Although the Duke and his entourage dutifully demurred when Simcoe offered them accommodation in his humble abode the Governor would not hear of them residing elsewhere. He declared emphatically that they must "remain with him, sleep in his house, and consider themselves as at home." And so they did remain in Upper Canada from the 20th of June until the 22nd of July. Mrs. Simcoe understood the necessity of playing the happy hostess to the Frenchmen for her husband had been directed to pay every attention to the needs of his special guests. Nevertheless she was less than pleased with their foreign visitors whom she declared were

In Her Own Words"perfectly democratic and dirty. I dislike them all."

Elizabeth was able to hide her hostility towards them and the duke was none the wiser. The Duke left us a detailed diary of the things he saw and heard during his stay and his notes indicated he was delighted with Mrs. Simcoe whom he described as a handsome, amiable person who fulfilled all the duties of mother and wife with the "most scrupulous exactness." He noted that she assisted her husband in many ways including using her talents as an artist to draw maps and plans. While she was bashful and spoke little he declared she was a woman of much sense.

Rochefoucauld was also impressed with Simcoe whom he considered to be just, active, enlightened, frank and brave, a leader who had the "confidence of the country." He believed the Governor possessed all the qualities needed for one of his station. With his manner and methods, said the duke, the Governor was able to keep all the old friends of the King while neglecting nothing that would procure him new ones. The duke was impressed with Simcoe's friendly, sympathetic reception of new settlers from the United States, people he considered errant children whom the Governor always eagerly welcomed back to the fold of "their Old Father," by whom Simcoe meant King George III. The duke was quick to detect their feigned fondness for the 'Old Father,' noting that they professed attachment to the British monarch plainly for the purpose of getting a ticket for possession of land.

The duke did feel that Simcoe was somewhat extreme in his dislike of the United States which "he too loudly professes." According to the duke this included bragging about the number of homes he had destroyed during the Revolution a claim which Simcoe later denied making.

Rochefoucauld duke observed that in his private life Simcoe was simple, plain and obliging. He inhabited a miserable, wooden house that was formerly occupied by commissaries. His guard consisted of four soldiers who came every morning and returned to the fort every night. His servants were all privates in the Queen's Rangers. Simcoe lived in a noble and hospitable manner without pride or pretense.

The duke visited the "inflammable air outlet" above Niagara Falls which is known today as the Burning Spring. He described it as a "sulphurous spring" and speculated about its possible medicinal powers. The duke noted that even though medical treatment was available to the Native people they usually placed more faith in the 'draughts' they prepared themselves.

On the whole the duke thought the houses in Newark were fine structures particularly the home of David William Smith, attorney-general, whose size, elegance and "French-kitchen garden" made it much more distinguished than the others. The French visitor was unimpressed with York. he declared that its inhabitants were not of "the fairest character." He commented on the scarcity of schools and noted that the few there were taught only reading and writing for a dollar a month.

The duke sought permission to visit Lower Canada. Britain was at war with France and Lord Dorchester feared visitors from France might stir up strife in the French-speaking province, so he refused Rochefoucauld's Affronted by what he considered a diplomatic slight and rude rebuff, the duke left Kingston for Oswego in a huff on July 22nd.

In 1799 Rochefoucauld was allowed to return to France, where he resumed an active role in education, benevolence and reform. He subsequently published several volumes of his journeys in North America and died at the age of 80 in 1827.

The Duke's mother, Marie de la Rochefoucauld, was also known as Mille de La Roche-Guyon, La Roche-Guyon being the name of a picturesque village northwest of Paris on the Seine River where she had a manor. Fast forward to early 1944 World War II and the `Desert Fox,' Field Marshal Erwin Rommel. While Rommel supervised the construction of the Atlantic Wall, he located his command post at La Roche-Guyon and his luxurious headquarters was none other than the opulent manor which had belonged to the venerable La Rochefoucauld family. Rommel insisted that the family share the chateau with him and they proceeded to do so. Rommel's study was located in the lofty ducal hall. Smelling of dusty books and centuries of wax polishings the hall was draped with priceless tapestries and hung with precious oil paintings.

Rommel laboured at an inlaid Renaissance desk across which over the three centuries numerous historic papers must have passed. Undoubtedly among those dusty documents was the diary of the Duke de La Rochefoucauld-Liancourt containing the account of the travels he had made long ago and far away in that primitive little province of Upper Canada.

|

|

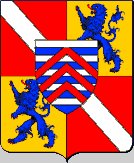

Rochefoucauld's Family Crest |

Copyright © 2013 Website Administrator