foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

LE COMTE DE PUISAYE

History reveals pieces of the puzzle that legend ignores.

Of all the names on all the historical markers that extend along the Niagara River Recreation Trail perhaps the one which creates most curiosity commemorates a refugee from the French Revolution. All that remains of his presence in this province is his gracious house on the Parkway. Constructed in the French style with massive walls, high roof and dormer windows, the house is now a historic site.

|

|

Le Comte De Puisaye |

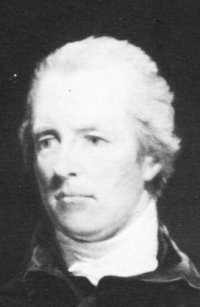

Le Comte Joseph-Genevieve de Puisaye was a French Royalist forced to flee from France during the French Revolution. Son of a marquis and a descendant of an ancient, noble family the Count, as he was called, was a tall, handsome, graceful individual whose polished, eloquent speech was enlivened by wit and sardonic humour. He was energetic and brave and had a passionate, aristocratic arrogance that alienated many. Elected to France's Estates-General in 1789 Puisaye favoured a constitutional monarchy and the preservation of the French monarchical society. He was appalled by the savage excesses in the revolutionaries and joined the counter-revolutionary movement. He became one of the most attractive figures in the resistance. Forced to flee France Puisaye escaped to England where he was enthusiastically received.

Impressive in dispute as well as appearance the Count proposed to the British government that it fund a royalist, seaborne invasion of France which he declared he was willing to lead. He stated that its success would spark a general insurrection, overturn the revolutionary republic and return the monarch to his magnificence. All he needed were three things: men, money and materials.

|

|

William Pitt the Younger |

Prime Minister William Pitt thought him a "clear and sensible man" and was greatly taken with his proposal. Henry Dundas, Minister of War, was much less impressed and labelled Puisaye's plan "an adventure." Pitt's views prevailed and de Puisaye's plan was backed with ships and supplies. However, Pitt refused to incluce British soldiers. Clearly he had reservations about the outcome of the invasion with good reason.

On June 8, 1795 Puisaye took on board approximately 3500 men wearing British uniforms. He counted on about fifteen thousand men but they did not appear. Many of the emigrants were secretly hostile about cooperating with the British and called "the man Pitt" their 'black animal' and refused to serve. Others were supposed to join them in France and increase the military manpower of the royal army to ten thousand men.

The the sovereign's supporters landed on Quiberon peninsula in southern Brittany. They hoped the peasant armies of Brittany would welcome them and march on Paris with them. They attempted to set up a base from which it was hoped an uprising would be fomented that would fan out through the rest of the country and result in massive support for the sovereign.

|

|

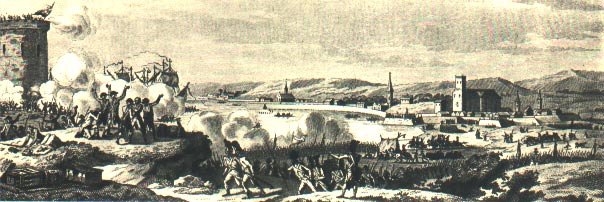

Quiberon |

Instead the assault was a farce and failed miserably. They wasted time in Quiberon while the republican forces closed in on them. They let themselves be trapped on the narrow peninsula, unable even to deploy in fighting formation. There the republicans got in among them and massacred them. Thousands of the Bourbon king's followers either drowned or surrendered and were promptly shot. Puisaye fled to England supposedly to save official correspondence, but some suggested he was motivated more by cowardice than correspondence. The routed royalists sought safety and refuge in Britain.

|

|

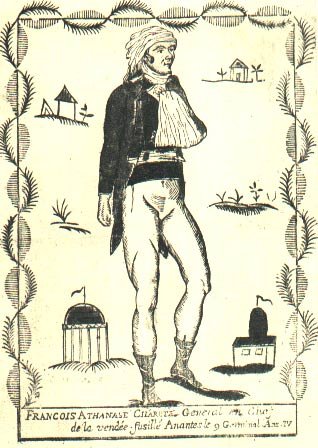

French Fiasco> |

Before long these French emigres as they were called became a heavy financial charge on the public purse and on private charities. Once again Puisaye proposed a possible solution. He petitioned for the establishment of a French military colony in Upper Canada where

In His Own Words"the air was less impure than that of Europe."

It was hoped the emigres would become self-supporting colonists and help defend British North America from the contaminating influence of republican principles that were seeping up from the south. These French 'Loyalists' were to be settled in Upper Canada on the same terms as the Loyalists who had fled from the American colonies.

On the 22nd of November 1798, the Executive Council of Upper Canada appropriated the townships of Uxbridge, Gwillimbury, part of Whitchurch and one unnamed township in the rear of Whitby. These lands were to be reserved for refugees "whose character and behaviour appear to entitle them to the King's beneficence because they endeavoured to maintain the cause of the late King of France against his ferocious oppressors just as American Loyalists had supported their sovereign against the swindling transactions of the American Revolution with its bitter fruits."

The 1799 Gazetteer informed its readers that "lands have been appropriated as a refuge for some French Royalists and their settlement has commenced." Named "Windham" in honour of the British secretary of war who befriended the emigres, the settlement was to be situated half-way between French-speaking settlements in Lower Canada and those on the Detroit River. The French Loyalists were to be located fifteen miles north of York so that these well-armed Frenchmen could protect the capital from a northern attack. At the same time they would be near enough to be kept under close scrutiny by British authorities in York. Members of the Executive Council wanted to ensure that "all their movements could be subjected to the immediate inspection and control of the Administration." The French emigres were to be closely watched by a nervous natives at York who had real reservations about so many well-armed Frenchmen in their midst.

Led by Lieutenant-General le comte de Puisaye forty persons set sail for Canada in the summer of 1798. It was expected they would form the vanguard of an anticipated flood of refugees from France to Upper Canada. Ironically their safe passage to sanctuary in Canada was threatened by privateers, pirating vessels owned by fellow Frenchmen roaming the seas in search of British vessels to raid and rob.

|

The French Loyalists arrived safely at Quebec on the 7th of October and immediately commenced preparations for their trip to Upper Canada. There were accusations that prior to their departure the emigres had been "tampered" with by French Canadians who attempted to dissuade them from going to Upper Canada by warning them against going to "that sickly, bad country" and pressured them to relocate in Lower Canada. They were after all French and French Lower Canada was the rightful place for them. The emigres haughtily dismissed these appeals. This was explained by the British minister Mr. Windham who described them as "a purer description of French Loyalists than the common mass of French emigrants." They were reluctant to mix with the masses of la belle province whose principles and conduct they did not know.

Because of the lateness of the year the emigres' trip to York was expected to be long and difficult in cold, raw, wet weather. Fortunately for the French newcomers fresh winds and the finest fall weather imaginable prevailed and they arrived without mishap at Kingston where they spent the winter at the military fort whose commander was ordered to "afford them every assistance in his power." Puisaye proceeded on to York where he arrived on the 18th of November. He immediately attempted to acquire an alternate location and his persistent requests for better land and bigger grants became an increasing source of irritation to the governors with whom he dealt. Puisaye himself received 5000 acres but he was dissatisfied with the site of the proposed settlement and attempted unsuccessfully to negotiate with Joseph Brant for a shoreline tract in the area of Burlington Bay.

Some members of the Legislative Council were unwilling "to sanction putting arms into the hands of Foreigners with whom they are so little acquainted." However because British officials in London supported this course of action they were armed albeit reluctantly. Local apprehension about arming the emigres was increased when Puisaye promised to establish a military corps of some 1000 French Royalists in the very heart "du haut Canada."

By May 1799 there was growing official concern that the French settlers "did not seem united." Puisaye was criticized for leaving his followers "to shift for themselves," while he spent most of his time on property he purchased from an American Loyalist on the river road some three miles south of Newark. Here he oversaw the building of a home and the development of his farm while he dabbled in trade and composed his memoirs.

It would have been difficult to find settlers less suited to life as pioneers. All including a marquis, a count and several viscounts were aristocrats who expected to find estates where the manual labour would be performed by others. The back-breaking labour of eking out a living was not for them. Its members lacked the muscle, motivation, skills and stamina needed for frontier farming and as a result their ill-starred settlement was destined from the beginning to fail.

|

|

Comte de Puisaye's Home, Niagara Parkway> |

After felling a few trees they looked at their blisters and abandoned the project. The hardship, privation and isolation sapped their strength and morale and by 1802 only sixteen of the original emigres remained at Windham. In 1814 with the great news that France had become a monarchy again many of the French settlers gave away their farms or left them as they were and "with all the eagerness of children long away from home" they hurried home to La Belle France. A few others settled in Lower Canada. One committed suicide because a young lady with whom he was infatuated in the extreme had discarded him. Over the next few years the colony continued to decline as the anticipated influx of new French settlers failed to occur. For the most part De Puisaye's people flitted "like satin butterflies across the bleak setting of early York and Yonge Street." Their place was taken by individuals with immense capacity for work and proven competence as farmers.

Puisaye returned to England in May 1802 supposedly in search of more financial aid. He decided to remain there and marry his housekeeper who had served him throughout the years at Niagara. He lived out his life on a farm 15 miles north of London "amid my chickens and cows." He published a six-volume historical narrative of his adventures in which he defended his failures and grandiose ambitions by disparaging the work and worth of others. His memoirs provoked considerable criticism in pamphlets and periodicals published at the time. On September 13th 1827, Puisaye died after a long, painful illness at Hammersmith in the environs of London. It was said of him that he left a small number of friends and a larger number of enemies.

Copyright © 2013 Website Administrator