foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

JOHN BUTLER

History deals with the world man has fashioned for himself.

Sir Guy Carleton described him as "very modest and shy." American historians saw another side to this Loyalist leader whom they labelled "diabolically wicked and cruel." He and his son, Walter were so feared it was said there was more rejoicing among the Yankee rebels of the Mohawk valley at the death of Butler's eldest son than at the surrender of British General Lord Cornwallis at Yorktown. The object of this bitter and understandably biased hatred was John Butler the renowned leader of Butler's Rangers and the scourge of the rebels.

|

|

John Butler & Sir Guy Carleton |

On land purchased from the Mississaugas corpulent old Colonel John Butler chose a princely 24,000 hectares at Two Mile Creek not far from Navy Hall which he named Butlersbury after the lost and lamented property he once owned on the Mohawk River in the colony of New York. Butler became the pillar of the small community he founded and fostered where the waters of the Niagara River meld with those of Lake Ontario.

The squire of Butlersbury was baptized in New London, Connecticut on April 28th, 1728. His father, Walter, a proud Irishman descended from the Dukes of Ormonde, was a captain in his Majesty's forces and commander of Fort Hunter on the Mohawk River in New York. Walter was determined to provide a suitable inheritance for his five year old son, John.

In 1742 Captain Butler brought his family to Mohawk Valley, where he became a close friend of hawk-nosed Sir William Johnson, Superintendent of Indians. Johnson, a tall, strong person, had ambition, energy, and a very an active mind. In addition he had a remarkable influence over his neighbours, the Natives of the Five Nations. John received his early education about the Aboriginals from Sir William who became so impressed with the boy's

|

|

Sir William Johnson |

diplomatic and linguistic abilities he used him as an interpreter at meetings with the Iroquois. It was not long before John became Sir William's lieutenant and during the Seven Years' War he rose to the rank of captain. He was present at Fort Niagara in July, 1759 when Sir William accepted the surrender of the French post which was situated right across the river from Butler's future settlement and ultimate resting place.

In 1763 at the end of the Seven Year's War, Butler continued his work with the Indian department and settled with his wife Catherine, their two sons and three daughters near the site of Fonda, New York. The Butler's rambling two-storey home called Butlersbury, overlooked the Mohawk River and the five thousand acre estate he had inherited from his father Walter.

The estate was all that remained of Walter's 86 thousand acres, huge holdings referred to as `rum-treaty' property which Walter had acquired at a merry, three-day "feast of brotherhood." Walter's invitation to this party, which was written on wampum, had been forwarded to him by the local Native chiefs. During the course of their revelling, several sachems signed over to Walter this great parcel of land in exchange for various gifts and promises of more to come. The chiefs sealed the deal by drawing their clan symbols on the bottom of Butler's parchment document. This contract had been officially approved earlier by New York's Governor Cosby, whose compensation for his kind approval was a kickback of 14 thousand acres.

John retired for a time from the Indian department in order to devote himself to his wheat crop and his harvest of hardwood lumber logged from a forest tract of three thousand acres. During this period, John was appointed justice of the peace and later when Tryon County was established he became justice of the Court of Quarter Sessions. He was also commissioned lieutenant-colonel of a militia regiment.

John Butler was described by an acquaintance as below middle height and somewhat corpulent, but active none the less. His perpetually worried look reflected a driving ambition. He spoke very quickly, often repeating his words when he was tense. He was a man of courage, force and firmness who drove himself and others in a relentless determination to succeed. He was politically astute and very ambitious, his carefully calculated actions always influenced by his own or his family's ultimate fortunes.

When the American Revolution began, Butler along with other Loyalists including his sons, Thomas and Walter, joined the British forces in Canada. John's handsome elder son, Walter, became a law clerk in Albany. John's wife Catherine and their daughters chose to remain at Butlersbury, New York where Catherine believed they would be safe.However, within a short time Butlersbury was plundered by the rebels and Catherine was taken "in custody" by the Provincial Congress in lieu of "Butler's bail bond." Mrs. Butler and the children were interned under house arrest at Albany in 1776 and only released on a prisoner exchange in June 1781.

As acting superintendent of the Six Nations, Colonel Butler was assigned the task of keeping the Native warriors out of the war and loyal to Britain. Operating from his base at Fort Niagara, Butler was successful not only in maintaining the British-Native alliance but in establishing a network of Aboriginal agents from the various tribes that stretched from the Mohawk to the Mississippi River. Intelligence information received from these agents was very useful to the British government and to Loyalists fleeing into Canada. When Britain decided to use the Natives offensively it was Butler who persuaded large numbers of them to participate with the King's forces in raiding expeditions against the Continentals. Skilled in field and forest, they fought ruthlessly with bayonet and scalping knife providing the stuff of legend as well as history. After they acquired firearms they applied the techniques of the hunt directly to warfare using concealment, harassment, ambush and dispersion with devastating effect. "They come like foxes in the woods. They attack like lions. They flee like birds." European armies lurched into disaster lured into the forests where their firepower was limited if not neutralized.

Aboriginal warriors forced tactical changes on European armies fighting in the trackless forests of the new world and wiser British commanders gradually adopted Aboriginal tactics. In September of 1777, Sir Guy Carleton approved the formation of a regiment of Loyalist Rangers to carry out frontier raids under Colonel John Butler. Mustered initially at Fort Niagara, the rangers wore fringed hunting shirts of green linen, leggings of buckskin or linen, moccasins and forage caps. When issued with parade dress their coatees were dark green cloth, faced with dark red, the officers uniforms of better quality material. The bucket-shaped forage caps were leather and engraved with 'G.R,' encircled by 'Butler's Rangers.'

|

|

|

Butler's Ranger in Parade Dress |

By March of 1778 Butler's Rangers had a complement of 300 men eager to avenge the mayhem the Americans were causing among the Loyalists. Together with Native sachems who willing took to the war path the Rangers carried out furtive forays over lonely forest trails throughout the valleys of New York and Pennsylvania. They carried out guerilla-type raids on horseback, hiding, striking hard and vanishing in country they knew like the back of their hands. Condemned by the Americans as murderous treachery the backwoods warfare conducted throughout the Mohawk valley by John Butler and Joseph Brant was hard and often heroic. Operating over great distances in all kinds of weather and conditions the furtive forces were in constant danger of interception and reprisal by marauding American militiamen.

The Rangers' mission was clear: "Seek out and destroy." Their hit-and-run raids wreaked havoc and great hardship on the Continental cause. The tough, resourceful Loyalist leaders and their Iroquois allies conducted devastating forays which while not sufficient to change the course of the war drew off rebel troops from more critical offensives, and diverted supplies from the Continental army. Even General Washington confessed that their assaults "threatened alarming consequences" for the American cause. Homes were burned, crops were destroyed and inhabitants of the countryside supporting Congress were terrorized. The reputation of the raiding parties was such that during the war one community with a population of 10,000 declined to 3500 as its fearful citizens sought safety elsewhere.

Loyalists' raids grew more severe as reports reached Butler and his men of the savage actions of Committees of Safety, cruel rebel inquisitors who used any means to force the betrayal of"Tory spies" and wring out confessions of British plans. Fort Niagara was the principal base from which John Butler, his son, Walter and Chief Joseph Brant rode the whirlwind as they launched incursions into the frontier settlements. The important impact of all these raids resulted in Congress diverting thousands of regular soldiers to fight these roving bands on the frontier. This eventually resulted in a defeat for Butler near Elmira, New York and the devastation of all Native villages in the Finger Lakes region of New York State. In spite of this the raids continued without letup from the Hudson River to Kentucky.

One of Butler's objectives was the rescue of Loyalist refugee families who had forsaken their homes in the Mohawk valley for the sanctuary and safety of the British fort. Hundreds of women, the elderly and children had been left to the "untender" mercies of the rebels and the Rangers expended every effort to rescue them. These raids infuriated Americans for generations after the war and earned John Butler and his son, Walter, reputations as "devils of Niagara." The "infamous Walter N. Butler" became a dark, mysterious, omen of evil who according to his opponents rode through the countryside wreaking havoc and heartbreak.

Walter, a well-educated young lawyer was devoted to friends and family. This sturdy, audacious, far-sighted young man believed whole-heartedly in his cause. He cried out angrily against this characterization in a famous letter written after the raid on Wyoming in Pennsylvania, where it was charged atrocities were committed.

In His Own Words"We deny any cruelties to have been committed here by whites or Indians.So far to the contrary not a man, woman or child was hurt after the rebels capitulated. Should you call it inhumanity to kill men in arms in the field we in that case plead guilty."

Walter was killed at West Canada Creek, New York, in 1781. There was great rejoicing in New York at this news since Walter had become the embodiment in people's minds of the horrors of civil war - roving bands of Tories and Natives prowling the valley causing death and destruction. American public opinion fixed on him as the fiend and made him a party to every midnight murder during the long years of the war. Despite John offering a large sum of money to any man who would deliver Walter's remains to Canada no one ever did. They were never found and opinions vary as to the whereabouts of Walter's body. Some say it was carried away by wolves while others contend it was secretly conveyed to St. George's Church in Schenectady where it was buried "under the third pew from the front in the right aisle."

A later rector of St. George's Church made up the following jingle.

Beneath the pew in which you sit,

They say that Walter Butler's buried.

In such a fix, across the Styx,

I wonder who his soul has ferried?

And so the ages yet unborn

Shall sing your fame in song and story,

How ages gone you sat upon

A Revolutionary Tory.

John Butler's interests were wide and never confined merely to the military. Even during the thick of fighting his mind was on money. He endeavoured to gain a monopoly on trade with the Loyalists living at Fort Niagara and to improve his relationship with the Indian department in order to monopolize barter trade with local Aboriginal tribes. Butler obtained permission early in the war to construct accommodation on the west side of the river for "distressed families" who had fled from the fighting on the frontier. To encourage farming near Fort Niagara Governor Haldimand authorized soldiers to settle in that vicinity. Ranger private Peter Secord was the first soldier to do so.

Butler requested approval to settle Rangers of "advancing in age." Haldimand approved division of land into lots for settlement providing it was understood that the land remained the "sole property" of the Crown. The offer was accepted and Butler reported regularly on the growth of settlement at Niagara. On August 25, 1783 he reported that 236 acres of the Niagara riverbank had been cleared and planted. Crops were expected to total 206 bushels of wheat, 46 bushels of oats, 925 bushels of corn and 632 bushels of potatoes. Livestock in the area totalled 49 horses, 42 cows, 30 sheep and 103 hogs. When the settlers pressed for sole ownership of their farms Butler supported their petitions for permanent possession of the land. This was finally authorized under the Royal Instructions of July, 1783.

Butler's Rangers were mustered for the last time and disbanded on 24 June, 1784. By the time of the first large influx of Loyalists into the Niagara region, Butler and his Rangers were well established there and their contribution to the area was already significant.

Butler was responsible for negotiations on behalf of the Crown with the Mississauga Aborigines for the purchase of additional land for settlement. The Missisaugas were originally a northern people of the Ojibwa or Chippewa tribes. Both names are forms of the same word which signifies "People whose moccasins have puckered seams". They had settled in the region sometime before the Seven Years' War. Negotiations dragged on for a lengthy period until finally at a Great Council Fire at Niagara on May 22nd, 1784 Butler addressed the assembled chiefs of the Missisauga [People of the large river mouth] tribe.

In His Own Words"Children, since I have already explained every circumstance as clear as light to you I expect your immediate answer."

The 'circumstance' to which Butler referred was the proposed purchase by the British government of an extensive "tract of country" owned by the Missisaugas located between Lakes Ontario, Erie and Huron. The grand council meeting had been preceded by snail-like negotiations that had taken place over many months pertaining to the various terms and conditions of the sale. Finally the objections of a few dissident Missisauga chiefs were overruled, and the details satisfactorily settled.

Council proceedings were brought to a close by Pokquan, a Missisauga chief. Before the assemblage which included Six Nations people Butler, his advisors and a number of other Missisauga sachems, Pokquan rose and with great dignity declared, "Father, we are willing to transfer our right of soil and property." Much of the land in question extended six miles deep on each side of the Grand River, stretching from the mouth of the river on Lake Erie back to its source.

|

|

Thayendanegea, Joseph Brant |

Turning to the great Mohawk warrior and chief of the Six Nations, Joseph Brant, Pokquan said

In His Own Words"This land is to be transferred to Thayendanegea and our Brethren in the hope they will always live in friendship."

Britain purchased the land and immediately transferred it to the Six Nations people as gift to their faithful Native ally for supporting the British against the Americans. It was to provide "a Fertile and Happy Retreat" where the Six Nations could settle, hunt and live in fellowship with the Missisauga "as Brethren ought to do."

The remainder of the property which was purchased at a cost to the British taxpayer of 1180 pounds was to be for the use of the "King's people," prominent among whom were John Butler and his Rangers. Governor Haldimand declared In His Own Words"It is my intention to settle such part of Colonel Butler's Rangers on the tract of land purchased from the Messessague Indians opposite to Fort Niagara."

Butler's stature a colonel of the Rangers during the Revolutionary war and as chief negotiator with the Natives was never fully recognized in the ranking he received in the little settlement he founded at Niagara. In 1786 Haldimand had considered appointing him superintendent of the Northern Indian Department but he decided not to because Butler was "deficient in Education and the liberal sentiments." While Butler was certainly a personage of importance his ongoing rivalry with Sir John Johnson, son of Sir William Johnson, and trusted adviser to Governor Dorchester prevented Butler from gaining any really important power in the new society on the shore of the Niagara River.

Butler's rank and military exploits failed to be as significant as he might have hoped for unlike the hierarchical chain of command in the regular army where esprit de corps fostered a sense of solidarity and subordination, service in a guerilla-type organization like Butler's Rangers never really built a basis for allegiance and lasting loyalty. As reported by one army officer to Haldimand, "The Rangers' Corps was devoid of military discipline its officers having scarcely the most distant idea of such matters." Daring not discipline mattered most among men who fought with the stealth and cunning of wolves.

In addition Butler's behaviour throughout the campaigns failed to win him the support and allegiance of the men he led. His leadership left no legacy of respect or affection among those he commanded because he unfailingly focussed his efforts on advancing his own or his family's interests at the expense of subordinate officers. Butler's attempts to monopolize the Loyalist trade for himself and his merchant friends was remembered with anger by officers and men alike as was the biased selection of his sons and other favourites for promotion.

Appointments to local offices in the little settlement were made by the government in Quebec and Butler was shocked to learn that the really important ones did not go to him or his men. Instead of the military officers assuming the leadership positions in the growing community, civilian merchants filled most of these roles. Butler was extremely disappointed to be omitted from the list of candidates that had been prepared by Sir John Johnson for seats on the Executive and the Legislative Councils.

While Butler never did achieve provincial prominence his prestige ensured that he was not excluded completely from management matters in the new colony. He was appointed justice of the court of common pleas and later lieutenant-colonel of the Lincoln county militia. While the latter position had great potential for power Butler's lack of contacts and close colleagues restricted his exercise of any real authority. When Butler was prevented by Johnson from advancing in the Indian department he tried to increase his family's fortunes by trading illegally with the Natives and by speculating on Iroquois lands in New York state. When these endeavours failed he turned to farming and milling, where he experienced little success.

Butler's growing infirmities threatened his position with Indian Affairs. In a letter to Dorchester in October 1795 Simcoe informed him that "Colonel Butler is so deaf he scarcely can interpret or speak in public Councils." In response Dorchester directed "that should Butler's age and infirmities not permit him to conduct Native business at Niagara with precision and regularity he must be prevailed upon to retire." The situation solved itself. Simcoe reported to Dorchester in April, 1796 "Colonel Butler is so seriously indisposed that there is little probability of his surviving his disorder." Butler died about nine in the evening on the 13th of May, 1796 at the age of 71. He was laid to rest in Butler's Burying Ground, now a historic site with a plaque in memory of his rangers.

|

|

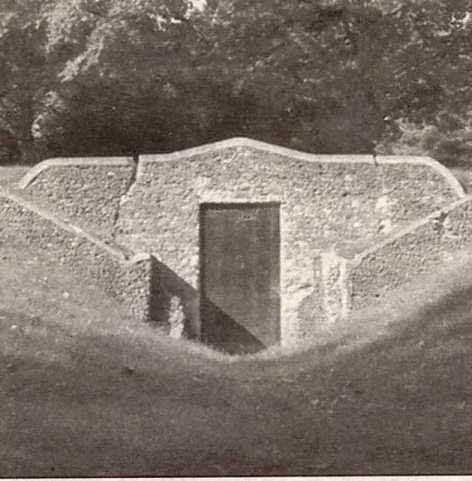

The Stone Crypt of Lieutenant Colonel John Butler [located at the end of the street that bears his name in NOTL] |

There is a brief mention of his burial in Mrs. Simcoe's diary: "Sunday, 15th Whitsunday, Col. Butler buried (His Majesty's Commissioner for Indian Affairs)" No blast from a bugler in a green coat by the lonely grave marked his passing with the Last Post. Native peoples recognized Butler as a man they could trust. At the Aboriginal burial ceremony for Butler Joseph Brant declared that Butler

In His Own Words"was the last that remained of those that acted with that great man, Sir William Johnson, whose steps he followed. Our loss is the greater as there are none remaining who understand our manners and customs as he did." In responding to this eulogy to someone who was "so conversant with your manners, customs and interests," Governor Simcoe praised Butler In His Own Words

"as a loyal and faithful subject to his sovereign and a true friend to the Indians."

Despite John Butler's frequent failures and frustrations he was one of the great figures in European-Aboriginal relations in North America, a fact that was clearly recognized by two governors, Sir Frederick Haldimand and Lord Dorchester. Both lauded his loyalty and deep sense of duty. Descendants of the Loyalists who served and settled with Butler at Niagara-on-the-Lake and elsewhere in the peninsula have ensured that his name will be linked in perpetuity with that of the Loyalists. The Niagara peninsula branch of the United Empire Loyalists' Association of Canada, decided their branch would honour his memory and bear with pride the name Colonel John Butler Branch.

|

|

Sir Frederick Haldimand |

There is a tablet to him in St. Mark's Church, Niagara-on-the-Lake.

"Fear God

Honour the King

In Memory of Colonel John Butler

A sincere Christian as well as a brave soldier he was one of the founders and the first patron of this parish."

Ontario Historical Plaque

Lieutenant-Colonel John Butler 1725-1796

By the end of the American Revolution John Butler's loyalist corps, supported by British regulars and native allies, had effectively contributed to the establishment of British control in the Great Lakes region. After the disbanding of Butler's Rangers in 1784, many of the men, including Butler himself, settled in the Niagara peninsula.

Copyright © 2013 Website Administrator