foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

THE ROYAL PROCLAMATION OF 1763

THE QUEBEC ACT OF 1774

History holds a mirror up to the dusty documents of the past.

THE PROCLAMATION OF 1763

The Proclamation of 1763 was in many ways Canada's first constitution.

|

|

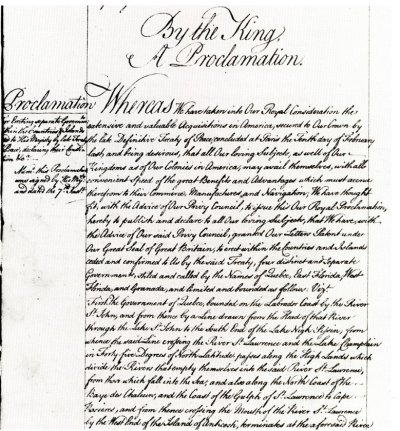

Proclamation of 1763 |

"WHEREAS we have taken into Our Royal Consideration the extensive and valuable Acquisitions in America, secured to our Crown by the late Definitive Treaty of Peace, concluded at Paris the 10th Day of February last; and being desirous that all Our loving Subjects, as well of our Kingdom as of our Colonies in America, may avail themselves with all convenient Speed, of the great Benefits and Advantages which must accrue therefrom to their Commerce, Manufactures, and Navigation, We have thought fit, with the Advice of our Privy Council, to issue this our Royal Proclamation, hereby to publish and declare to all our loving Subjects, that we have, with the Advice of our Said Privy Council, granted our Letters Patent, under our Great Seal of Great Britain, to erect, within the Countries and Islands ceded and confirmed to Us by the said Treaty, Four distinct and separate Governments, styled and called by the names of Quebec, East Florida, West Florida and Grenada, and limited and bounded as follows, viz.

First — The Government of Quebec bounded on the Labrador Coast by the River St. John, and from thence by a Line drawn from the Head of that River through the Lake St. John, to the South end of the Lake Nipissing; from whence the said Line, crossing the River St. Lawrence, and the Lake Champlain, in 45 Degrees of North Latitude, passes along the High Lands which divide the Rivers that empty themselves into the said River St. Lawrence from those which fall into the Sea; and also along the North Coast of the Baye des Châleurs, and the Coast of the Gulph of St. Lawrence to Cape Rosières, and from thence crossing the Mouth of the River St. Lawrence by the West End of the Island of Anticosti, terminates at the aforesaid River of St. John, etc. etc. etc. Given at our Court at St. James's the 7th Day of October 1763, in the Third Year of our Reign.God Save the King

The Indian war was still in progress when King George III issued his proclamation, word of which did not reach Canada and come into effect until the 10th of August 1764. It was Pontiac's revolt and a desire to pacify the Indians rather than a careful examination of the new problems of colonial government which produced the Royal Proclamation of 1763. Its formulators attempted to appease the Indians around the west of the Great Lakes by granting them territorial guarantees. Further colonial settlement was prohibited west of a line along the headwaters of all the rivers draining into the Atlantic Ocean from the Allegheny Mountains. King George reserved the western lands to the "several nations or tribes of Indians" that were under his "protection" as their exclusive "hunting grounds."

The Proclamation laid down entirely new and equitable methods of dealing with the Indians. It established a constitutional framework for the negotiation of Indian treaties. As such it has been labelled an "Indian Magna Carta" or and "Indian Bill of Rights." [*]

The Proclamation set out set out a procedure whereby an Indian group, if they freely chose, could sell their land rights to properly authorized representatives of the British monarch. This could take place only at some public meeting called especially for this purpose. This established the constitutional basis for the future negotiation of of Indian treaties in British North America. No person was allowed to purchase land directly from them and only the government could grant legal title to Indian lands which first had to be secured by treaty with the tribes that claimed to own them.

By providing the Indians with the promise of a degree of security as the sole authorized inhabitants of the larger part of their ancestral lands, the British government hoped to stabilize the western frontier of the old crown colonies along the Atlantic seaboard. This decision was hastened by news that a number of Indians following Ottawa Chief Pontiac had successfully demonstrated their defiance of crown rule over their lands by seizing several British posts that had recently captured from the French. This action afforded a degree of protection from the landgrabbing expansionism of frontiersmen along the western boundaries of the 13 Colonies. The alternative to this action would have been the incurrence by the British taxpayer of an enormous expense to maintain law and order in the North American interior. Ulitmately it proved to be virtually impossible for Britain authorities to check the western boundaries of the 13 Colonies at the Royal Proclamation line and their attempt to do so was one of the factors that led to the American Revolution.

|

|

Proclamation of 1763 |

In addition to prohibiting settlement beyond the western 'line', the Proclamation established four separate colonial governments for the regions of Quebec, East Florida, West Florida and Grenada.

The Proclamation provided for the creation of civil government with a representative assembly and English law in these regions including the newly named Province of Quebec.

"As soon as the state and circumstances of the said colonies will admit, they shall with the advice and consent of the members of our Council summon and call general assembies in such manner and form as is used and directed in those colonies and provinces in America to make, constitute and ordain laws, statutes and ordinances for the public peace, welfare and good government of the people and inhabitants thereof."

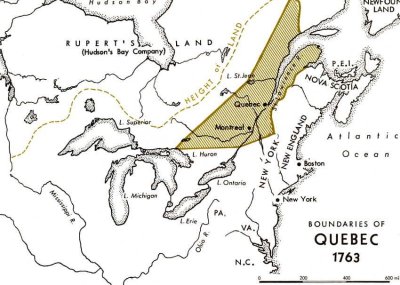

Quebec's western boundary was defined as a line running from Lake Nipissing to approximately the site of present-day Cornwall, Ontario. Its eastern limits did not extend beyond St. John's River at the mouth of the St.Lawrence nearly opposite to Anticosti, while that island itself and the Labrador country east of the St. John's as far as the Straits of Hudson were placed under the jurisdiction of Newfoundland. The islands of Cape Breton and St. John, now Prince Edward Island, were subject to the government of Nova Scotia which then included New Brunswick.

|

|

James Murray |

|

|

Sir Guy Carleton |

In spite of these provisions there was no representative assembly formed in Quebec and French civil law continued to be used along with English criminal law. When it seemed clear that no large numbers of English settlers would come to Quebec, the promise was overthrown. The governor, General James Murray and later Sir Guy Carleton were more partial to the more easily-governed French residents than to the troublesome merchants with their persistent demands for change and they ignored the terms of the Proclamation relating to representative government. They were able to do this without opposition from the majority of French-speaking residents of Canada who had no conception of representative institutions in the English sense and were quite content with the existing military system of government that left them their language, religion and civil law. It was considered of the utmost importance to secure the loyalty of the population and Murray believed this could be done by satisfying their leaders, the clergy and the seigneurs.

In the wake of the British army, more and more British and colonial American merchants moved into Quebec and before long they began to dominate the western fur trade and the import and export trade. At first there was little friction between these newcomers and the French residents because the English-speaking and French-speaking Canadians became economically linked and interdependent. However, as the English-speaking population of colonial Americans and British settlers grew, they began to resent the restrictions of military rule and Murray's favouritism towards the French and pressed for changes. For them the all-important question was the form of the proposed government. Murray saw them as "licentious fanatics" who were determined to destroy his authority and the French cultural fabric of the colony. However, their clamour reached London and in 1765 Murray was recalled and replaced by Sir Guy Carleton.

Sir Guy Carleton arrived in Quebec in mid-1766 and for a time tranquility reigned. Like Murray Carleton feared a renewal of war with France and he felt it was necessary to strengthen Quebec by securing the loyalty, cooperation and support of the 'new subjects", who could he believed provide an army of some eighteen thousand men if necessary. This entailed keeping the allegiance of the seigneurs and clergy who seemed to be the key to getting this support.

The Proclamation of 1763 had stressed the introduction of English law and an elected assembly with the idea in mind that English-speaking settlers would stream into Britian's new colony. When this failed to happen Carleton believed the French Canadians would feel more secure and be more supportive of colonial government with a return to the semi-feudal autocracy, state church and the civil law of the French regime. He returned to England to recommend these provisions and achieved his goal with the passage of the Quebec Act of 1774.

ANNO DECIMO QUARTO

GEORGE III. REGIS

SEVENTH DAY OF October in the Third Year of His Reign

Thought Fit To Proclaim

THE QUEBEC ACT OF 1774

An act for making more effectual provision for the government of the Province of Quebec in North America

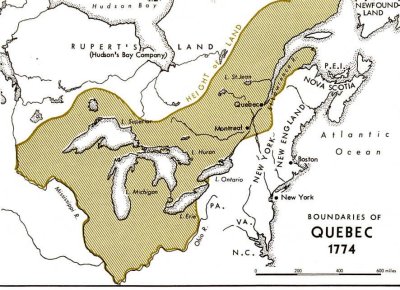

The Quebec Act of 1774 dealt with the old French Canadian empire and its original owners the Aboriginals. Most of the latter lived in the huge pocket of land lying below the Great Lakes. All were members of proud tribes and were determined to resist further white encroachments on their traditional hunting grounds. The British were anxious to respect their strength and to prevent any reoccurence of the bloody wars on the American frontier that had been enflamed by the eloquence of Pontiac raging against white entrenchment. They wanted to head off continued Indian wars caused by American frontiersmen flooding into the wide open western spaces of the Ohio country. In order to do so the British used the Quebec Act of 1774 to broaden the boundaries of Quebec as indicated by the shaded areas in the maps below by extending the boundaries set out in the Proclamation of 1763 to the line of the Ohio River.

The preamble of the Quebec Act fixed new territorial boundaries for the province. Under it Quebec would comprise not ony the country mentioned in the Proclamation of 1763, but also all the eastern territory previously annexed to Newfoundland. In the west and south-west the province was extended to the Ohio and the Mississippi including all the land beyond the Alleghanies that was so eagerly coveted and claimed by the old English colonies which were now hemmed in between the Atlantic and the Appalachian range.

|

|

Quebec Act, 1774 |

The Quebec Act occupies a special place in the catalogue of Canadian acts. It was the first Imperial statute to create a constitution for a British colony. It was passed at a time of crisis involving the 13 Colonies of which, some said, it was major cause. It was also the first parliamentary statute to recognize the complexity of relations between the two groups that comprise Canada. Jean Charest, the Premier of Quebec, has called it the most fundamental document in Canadian history. It has aroused much interest and much controversy. It is, therefore, considered a key piece of legislation by Canadian historians.

Under this act Quebec received distinctive treatment. There was complete acceptance of authoritarian rule. The Quebec Act essentially reversed the earlier provisions designed to creat uniformity among the North American colonial governments - uniformity based on English institutions. It was made with good intentions but it was both criticized and acclaimed from the moment it appeared. In approving it the British government had heeded the advice of James Murray, Quebec's first English governor and Sir Guy Carleton his successor and ignored the peititions and pleadings of a small group of English settlers, mainly merchants, who opposed it. The act confirmed to Canadians the free used of their language, their customs and their Roman Catholic religion. It granted them most of the old French civil laws including the seigneurial tenure of land. It ensured the rights of the clergy to collect tithes and it offered the people an oath of allegiance that contained no insulting religious clause. According to the new act Quebec reverted substantially to the traditions of the French regime - rule by the governor and appointed council rather than by an elected assembly. It guaranteed the primacy of the church as well as French property and civil law. The privileges of the seigneurs and the system of feudal land tenure were guaranteed.

The matter of an elected assembly was set aside. Carleton opposed colonial assemblies. In his letter to the British government on January 20, 1768 he wrote, "The better sort of Canadians fear nothing more than popular Assemblies, which, they conceive, tend only to render the People refractory and insolent. Enquiring what they thought of them, they said they understood some of our Colonies had fallen under the King's Displeasure, owning to the Misconduct of their Assemblies and that they should think themselves unhappy if like Misfortune befell them." Carleton believed that the British form of Government transplanted to Quebec would never produce "the same Fruits as at Home" chiefly because he felt it was impossible for the "Dignity of the Throne or Peerage to be represented in the American Forests." In the colony, he said, the Governor had little or nothing to give away so he would have little influence. It was, therefore, critical that he retain all in proper Subordination, that is, that the power remain in his hands.

Unlike those who believed the French-speaking Canadians would eventually become assimilated into a majority of English-speaking immigrants, Carleton saw no likelihood of that happening.

"There is not the least probability this present superiority (French Canadians) should ever diminish. On the contrary 'tis more than probable it will increase and strengthen daily. The Europeans who migrate will never prefer the long, unhospitable Winters of Canada to the more cheerful Climates and more fruitful soil of his Majesty's Southern Provinces. While the severe Climate and the Poverty of the Country discourages all but the Natives, its Healthfulness is such that the Canadians multiply daily so that barring a Catastrophe shocking to think of, this Country must to the end of Time be peopled by the Canadian race."It was difficult to know just what the majority of Canadians actually felt about an assembly. Few could read and the majority had no knowledge whatsoever of democracy nor the principles on which it worked. It could be claimed by anyone, therefore, that they were uninterested in adopting them. They had always been ruled by a king's deputy and his little court at Quebec and as long as their rule light they preferred it. When this was replaced by a governor and council appointed by the British crown, they readily accepted it.

During debate on the bill in the House of Commons the most contentious issues involved the use of Canadian civil law (criminal law was to be based on English law) and refusal of an assembly. There was also criticism of the provision to extend the province's boundaries to include the Ohio and Mississipi country.

While the terms of the act were considered a matter of simple justice to the Canadians, some suggested that with them "the seeds were sown that flowered like stubborn weeds ever since."

In French Canada the act was received without any popular demonstration by the French Canadians. On the whole the Quebec Act satisfied only the upper class French Canadians. The lower class found nothing in the Quebec Act to cheer about. The habitant had mixed feelings about it, for while it gave him security of his language and religion it also revived certain objectionable feudal privileges of the seigneurs. The habitant disliked the governor's defence measures which involved forced labour and the requisitioning of supplies and the prospect that he might be forced into the army. The men to whom a great body of people always looked for advice and guidance - the priests, cures and seigneurs - naturally regarded the Act's provisions as evidence of a considerate and liberal spirit in which the British government was determined to rule the province.

Of great importance to Canadian history was the fact that the Act meant the province of Quebec was being treated in a special way by an imperial act of parliament.

|

|

House of Commons |

This complicated the future development of Canadian government for the chance from the beginning to fit Quebec into the ordinary pattern of British institutions had been lost. In their assessment of the Act, some Canadian writers and historians will be influenced by its effect on the subsequent history of Canada. While there was never any likelihood of completely assimilating French Canadians into an English-speaking Canada, the future co-operation between the two language groups was made more difficult by this measure which increased the French feeling of separateness.[**]

The Quebec Act of 1774 was made with good intentions, but it was both criticized and acclaimed from the moment it appeared. In approving it the British government had heeded the advice of James Murray, Quebec's first English governor and Sir Guy Carleton, his successor, and ignored the peititions and the pleadings of a small group of the English settlers, chiefly merchants, who opposed it. Unfortunately, evidence is scarce on the views and motives of those who gave the Act its final form. The papers of Carleton would have been invaluable but they were destroyed by his wife after his death in accordance with his wishes.

The denial of representative government infuriated the merchant class who protested that the mother country had deprived them of a basic right of all Englishmen. However, two important provisions took some of the edge off their discontent. The more humane English criminal law replaced the relatively harsh French penal code. By far the most attractive features of the Quebec Act were the territorial changes. The Act's extension of the boundaries of the colony included the rich fur-trading territory between the Ohio and the upper Mississippi rivers which had formerly been part of the French empire. This meant the merchants in Canada were now able to exploit the fur trade in this area without fear of competition from the merchants of Albany and New York. In addition to consoling the fur-trade merchants of Quebec this extension tied the Ohio country to a 'safe' province - Quebec. British concerns regarding the status of the 13 Colonies were already surfacing and with good reason.

The American colonies were enraged by these acts which they saw as moves on the part of the mother country to confine their settlement to the eastern coastal plain. In American eyes the Quebec Act became one of the final Intolerable Acts of Britain that sparked the revolution. In some ways it was the most intolerable of the Intolerable Acts since it seemed to be aimed at weakening not only Massachusetts, whose Boston harbour was closed following the Boston Tea Party, but all the Atlantic colonies. They declared the Act was "dangerous to an extreme degree to the civil rights and liberties of all America." By 1774 rebellion in the 13 Colonies was developing rapidly and the stifling of their westward expansion and was another sour ingredient added to the already bubbling pot. The Quebec Act contributed more, perhaps, than any other measure to drive them into rebellion against their sovereign. It led to an ominous step on the road to revolution: the calling of the first Continental Congress.

[*] This document is referred to in Section 25 of the Constitution Act 1982. This provision details that there is nothing in Canada's Charter of Rights and Freedoms to diminish the rights and freedoms that are recognized as those of aboriginal peoples by the Royal Proclamation 1763. [**]Canada A Story of Challenge by J.M.S. Careless [***] According to Jean Charest, Premier of Quebec,In His Own Words

"Canadians made a decision very early in their history, a choice that over time has come to define the very essence of who we are. Our ancestors decided right from the start to build a country based on the right to speak a different language, to pray in a different way, to apply a different legal system based on the French Civil Code, to belong to a different culture and to enable that culture to flourish. The Quebec Act of 1774 passed into law more than 200 years ago and almost a hundred years before Confederation is in this respect the most fundamental document in Canadian history. It is the foundation upon which the Canadian partnership was originally built. Its spirit defined this country from its very inception. It represents one of the most enlightened decisions ever made for Canada. Canadians should reflect upon this choice that was made so early in our history. We should reflect on how it defines us, how the French language and culture and the presence in the federation of a French-speaking province has allowed Canadians as a whole to extend their influence and play a greater role in the world community."

Copyright © 2013 Website Administrator