foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

THE CONSTITUTIONAL ACT 1791

History chronicles matters of timeless importance.

In 1759 after the bugles had blown to herald peace,

|

bells were pealed, bonfires burned and revelling erupted throughout Britain in celebration of Wolfe's triumph over the Marquis de Montcalm on the Plains of Abraham.

|

The nation had known many victories that year but none equalled the conquest of Canada. It finished France forever as an imperial power in North America. Britain's acquisition of New France was something of an accident in the fortunes of war and the diplomacy of peace. When public celebrations finally subsided doubts and uncertainty replaced exultation at the acquisition of this huge new colony. Prime Minister William Pitt had micro-managed the strategy for the war but neither he nor his successors had developed any policy for the peace.

|

|

Wolfe, Pitt, Montcalm |

A final decision regarding Canada was complicated by the fact that during negotiations neither side really wanted the colony for its own sake. France had found the Canadian colony so large it had become a financial drain on the nation's resources.

|

Pitt was undecided whether

In His Own Words

"to retain all Canada and Cape Breton Island and give up Guadeloupe and Goree {French sugar islands in the eastern Caribbean}, or retain Guadeloupe and Goree, give up some part of Canada and confine ourselves to the Line of the Lakes" by which he meant the land bordering the Great Lakes.

After lengthy deliberations the British government decided to retain Canada not for its own sake and its implicit commercial value but for the sake of the American colonies. Its possession ensured the security and welfare of Britain's older possessions along the Atlantic coast. Therefore on February 10th, 1763 "His Most Christian Majesty Louis XIV ceded and guaranteed to his Britannic Majesty George III, in full right, Canada."

|

Once the decision had been made to keep Canada, the British government pondered what to do with this foreign colony in a far off place. As one official put it, "Are we not the only people on earth except Spain that ever thought of establishing a Colony ten times more extensive than our own country and yet imagine that when it comes to maturity it will still depend on us?" The few English settlers - mostly merchants - who emigrated to the new colony were very disappointed that the government peace treaty guaranteed to the French Canadians maintenance of their institutions - the French language and laws - and their right to practice their religion.

The Quebec Act of 1774 was made with good intentions, but it was both criticized and acclaimed from the moment it appeared. In approving it the British government had heeded the advice of James Murray, Quebec's first English governor and Sir Guy Carleton his successor and ignored the peititions and the pleadings of the English settlers who opposed it. The act confirmed to Canadians the free used of their tongue, their customs and their Roman Catholic religion. It granted them most of the old French civil laws including the seigneurial tenure of land. It ensured the rights of the clergy to collect tithes and it offered the people an oath of allegiance that contained no insulting religious clause. The matter of an elected assembly was set aside for the majority of the Canadians had no knowledge of democracy nor the principles on which it worked and were uninterested in adopting them. They had been ruled by a king's deputy and his little court at Quebec and as long as their rule was it light they preferred it. This was replaced by a governor and council appointed by the British crown which they readily accepted. While the terms of the act were considered a matter of simple justice to the Canadians, some had suggested that with them "the seeds were sown that flowered like stubborn weeds ever since."

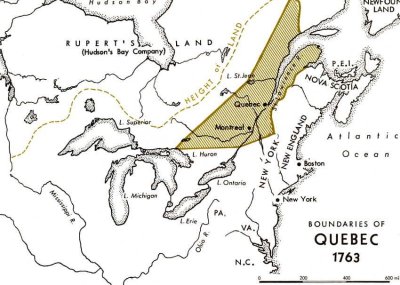

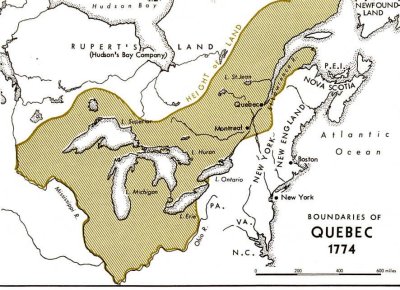

The Quebec Act of 1774 also dealt with the old French Canadian empire and its original owners the Aboriginals. Most of them lived in the huge pocket of land lying below the Great Lakes. All were members of proud tribes and were determined to resist further white encroachments on their traditional hunting grounds. The British were anxious to respect their strength and to prevent any reoccurence of the bloody wars on the American frontier that had been enflamed by the eloquence of Pontiac raging against white entrenchment. To head off continued Indian wars caused by American frontiersmen flooding into the wide open western spaces of the Ohio country, the British broadened the boundaries of Quebec as indicated by the shaded areas in the maps below by extending those set out in the Proclamation of 1763 to the line of the Ohio River with the Quebec Act of 1774.

|

|

Proclamation of 1763 |

|

|

Quebec Act, 1774 |

Over the years that followed little real interest was shown in the new possession. Other than the English merchants who pressed unceasingly for the implementation of English laws and government, no attempt was made to settle the land acquired by conquest. However, when the American rebels defeated the redcoats and won their revolution, their unexpected victory sent thousands of loyal refugees seeking safety from the vengeful victors fleeing north where they sought sustenance and security under the British flag. These Tory Americans had chosen King over Congress fully expecting that 'their side' would quickly quash the rebel uprising. The stunning and totally unforseen defeat of British regulars by the rag-tag rebel army forced the Loyalists to flee from the democratic tyranny to Quebec.

|

No event had a greater or more permanent influence on the destiny of the Canadian people than the revolting American colonies and their resulting independence. The new republic produced a second conquest of Canada by Americans, this time without the blast of trumpets and the thunder of cannons. The losing Loyalists, thousands of pitiful emigres seeking sanctuary and safety, streamed into the little settlements that hugged the shores of the St. Lawrence River where they found a society that was French and foreign.

Loyalists had a split personality: one was imperial and the other American. While they were conservative supporters of Britain's king and empire they were also North American in attitude and outlook and not at all politically submissive. They were accustomed in the 13 Colonies to having a number of liberties including the right to elect their own assemblies. They were not prepared to accept the situation they found in Quebec where elections were unknown, institutions were feudal and official decisions were made in an autocratic and mandatory manner. Loyalists found the colony with its French civil law and the seigneurial land-holding system offensive and intolerable. They protested that they were being deprived of their rights as British subjects and bombarded the government with letters and petitions appealing for the blessings of British laws, popular assemblies and free titles to their own lands.

|

Despite unremitting pressure for change from all sides, the Imperial government - the name of the British parliament whenever it transacted colonial business - hesitated to act since it was ill-informed on the actual state of affairs in Quebec. As early as 1788 the British government had considered dividing Quebec into two provinces but legislation was slow in coming. British merchants in Quebec opposed the division of the colony because it would leave them a small minority in a province dominated by the French-speaking majority. Finally the impassioned pleas and petitions for constitutional change from Loyalists who had lost all in support of their sovereign were heard and heeded.

|

Some thirty years after the conquest the Imperial parliament passed the Constitutional Act of 1791. Known initially as the Quebec Government Bill, this 31st Act of the King was written by William Windham Grenville. Prime Minister William Pitt had little time for Canada and he left the legislation largely to the industrious but unimaginative Grenville who was Secretary of State for the Home Office and Pitt's favourite cousin. The prime minister was preoccupied with the revolution in France raging across the English Channel and with the periodic insanity¨ of his sovereign George III with whom Pitt was not always on the best of terms. George III was jealous of anyone with ability and quick to perceive and resist any sign of independence in his ministers. He was less than enthusiastic about the Quebec Bill.

The CONSTITUTIONAL ACT 1791 GEORGE III XXXI Year of Reign

An Act for making more effectual Provision for the Government of the province of Quebec, in North America; and to make further Provision for the Government of the said Province.

"II. And whereas His Majesty has been pleased to signify, by His Message to both Houses of Parliament, His Royal Intention to divide His Province of Quebec into Two separate Provinces, to be called The Province of Upper Canada and The Province of Lower Canada, be it enacted by the Authority aforesaid,That there shall be within each of the said Provinces respectively a Legislative Council and an Assembly to be severally composed and constituted in the Manner herein-after described; and that in each of the said Provinces respectively His Majesty, His Heirs or Successors, shall have Power, during the Continuance of this Act, by and with the Advice and Consent of the Legislative Council and Assembly of such Provinces respectively, to make Laws for the Peace, Welfare, and good Government thereof, such Laws not being repugnant to this Act."

|

Grenville, whom John Graves Simcoe referred to as the "Founder of Canada" knew nothing about Canada nor colonies, but based his legislation on lessons seared into the souls of British politicians by the American Revolution. Primary among these was that excessive democracy was a dangerous thing. It was widely believed that too much, not too little legislative independence in the 13 Colonies had made the Americans ripe for revolt. It was felt that the revolution had been caused by very active colonial assemblies that had become too powerful.

It was Britain's intention to preserve loyal and contented colonies that were to be kept small, separate and dependent. Loyalty not liberty was to be stressed. It was vowed that this time lively democracy and dangerous radicalism would not be allowed to grow too strong. Colonies in future would be more completely controlled by the motherland. Democracy was described as "a serpent which could twist around us by degrees and that should be crushed in the first instance."

|

As was often the case when they tried to understand the meaning of history, British politicians learned the wrong lesson. They persisted in repeating with the Canadian colonies the same mistake that had lost them the American colonies. "The rock that had wrecked the first American colony was to become the cornerstone of the second." In short, the Constitutional Act was simply a refined re-run of the system of royal colonial government that had failed in the 13 Colonies. Like the Americans the people of Canada were to be subject to the vetoing powers of governors, un-elected councils and the Imperial parliament.

The second lesson British leaders believed they had learned from the Revolution involved "hereditary aristocracy." They considered the absence of an upper class of lords and ladies in the 13 Colonies to be one of the reasons for the revolution. Lord Grenville was determined to instil in the pioneer society respect for rank and privilege. He believed that class and social standing in the colony should descend in succession through the eldest sons of a few highly privileged families.

|

Legislative councillors could be chosen only from these noble families because it was believed they could always be counted upon to support their sovereign. Because of their privileged position these favoured few would have a personal interest in maintaining the established government with their unwavering support. This imitation aristocracy was expected to serve as a cure for any democratic constitutional contagion that wafted up from the republic to the south.

The British cabinet accepted Grenville's bill and sent it to the House of Commons in the fall of 1790 where its introduction was delayed because of a threatened war with Spain over territorial interests in North America.¨ It was finally brought before the House of Commons on March 4, 1791 by the prime minister himself.

|

|

House of Commons |

It was said that Pitt, who was described by a colleague "as chilling and impressive as an iceberg," looked across the ocean with those "wise eyes of his" and declared that the bill would "remove the differences of opinion which had arisen between the old and the new inhabitants of Quebec."

|

|

William Pitt the Elder (Lord Chatham) |

Towards the end of April the bill went into Committee but as usual with matters pertaining to the colonies, attendance in the House of Commons was sparse and sporadic and this resulted in frequent delays. When the debate did take place it was one of the most interesting and passionate in British parliamentary history. The record of it filled thirty-eight pages, however, only three of which dealt directly with the Quebec legislation. Hardly anyone talked about the bill itself. The debate was memorable because of the encounter which occurred between two parliamentary giants: Charles James Fox and Edmund Burke. The cause of their clash was not Canada for neither man knew much about the colony. Burke described it as being "bleak and barren." Others called it "the habitation of bears and beavers." Their argument was about the anarchy and uproar then shaking the very foundations of European society: the French Revolution. It had suddenly changed from being an exciting foreign spectacle into a major national issue.

Charles James Fox was a great liberal and the ablest debater of his day. While Fox was born an aristocrat, he was solidly behind reforming parliament to make it more democratic. In his early years he was something of a playboy who wore pink heeled shoes and blue hair powder. Later he gave up his dandified clothes for a plain blue coat and buff waistcoat, the same colours then worn by General Washington's army. Fox was an enthusiastic and impulsive person who strongly supported the American revolution and fully defended the French revolution.

|

|

Charles James Fox [1740-1806] |

Edmund Burke was described as one of most intelligent individuals ever to sit in the British parliament. Initially Burke defended democracy and was a strong supporter of the American revolution, but as atrocities mounted in France he recoiled in horror at the French Revolution. The anarchy and outrage taking place there appalled him and he developed a passionate hatred for revolutions and democracy.

|

|

Edmund Burke [1729-1797] |

In Burke's Own Words

"Our present danger is from anarchy - plundering, ferocious, bloody, tyrannical democracy. It is founded on the scorn of history. I set my feet in the footprints of my forebears where I may neither wander nor stumble. People will not look forward to posterity who never look back to their ancestors." Although Burke was of humble birth, he resolutely supported government by the aristocracy.

|

|

Burke (top) & Fox |

These old Whig campaigners had been close friends for twenty-five years and had fought many causes together. They entered the House of Commons on May 6th 1791 as comrades-in-arms prepared to debate the Quebec bill paragraph by paragraph. During debate on this "peaceful bill" violent passions were to erupt that caused their friendship to founder and fail.

|

Burke led off the debate but instead of discussing Canada's constitution, he launched into a tirade against the French Revolution. Despite being called to order he persisted in his impassioned attack on the French constitution. Various Members shouted rowdy reminders for him to stick to the topic at hand but without effect. Talk turned to tumult as Fox and other Members endeavoured to shout Burke down. A censure motion seconded by Fox served only to incense Burke who said he was being treated unfairly. He continued to rail against the revolution calling it "a foul, monstrous thing." Fox countered by shouting that it was one of the "most glorious events in the history of mankind." Burke's ranting turned to rage as he denounced the "chaos" occurring in France. Laying on the terror with a trowel Burke said that France was "swimming in blood, polluted by massacre and strewn with scattered limbs and mutilate carcasses."

Prime Minister Pitt looked on in amazement shocked but secretly satisified to see his two old adversaries furiously fighting with each other.

|

Burke's speech was the signal for Fox's ardent young band of radicals, whom Burke called "the little dogs," to howl and hiss. In the middle of his enraged rant, Burke caught sight of his old friend Fox taunting him and in his frenzied state the sight was too much for Burke to bear. He turned dramatically towards Fox and declared that a personal attack had been made on him from a quarter he could never have expected after a friendship of 22 years. Then he declared loudly, "this cursed French revolution envenoms everything," to which Fox remarked, "There is no loss of friendship between us." Burke replied: "I regret to say there is. I have done my duty. I know the price of my conduct. Our friendship is at an end."

Fox was visibly shaken by what his friend had shouted and a hush fell over the House as he rose to respond. Trembling with emotion Fox attempted to speak, but unable to utter a word, he slumped back distraught into his seat. There was hardly a dry eye in the galleries. Thereafter, whenever the two men met it was as complete strangers. Six years later when Burke lay dying of cancer of the stomach Fox rushed to his home hoping to end their quarrel before death did. Burke refused to see him. The end of the celebrated association between these two great parliamentarians ensured the lasting fame of our founding for their break-up occurred during consideration of our constitution.

The bill creating Canada was piloted through the House of Commons by Pitt himself. The document reflected the prime minister's attempt simply to avoid trouble with the colony rather than to create a new and nobler kind of constitution for the new Canadian colony. When they finally got around to considering it the legislation was sharply debated by Burke and Fox.

Pitt ignored the advice of British merchants in Quebec, who opposed the division which would reduce them to a minority in the new province, and divided the colony into two provinces in order "to reconcile the clashing interests" of the old French and the new British inhabitants." In the 13 American colonies the assemblies had found strength when they acted in unity. This would be prevented in Canada by using the concept of "divide and rule." This provision was greeted with great satisfaction by the French population of Lower Canada for it ensured they would enjoy a degree of self-government with their own legislative assembly.

|

Edmund Burke agreed with Pitt's decision to split Quebec. "To attempt to amalgamate two populations composed of diverse languages, laws and customs was a complete absurdity." Fox disagreed with both Pitt and Burke. He argued that the division of Quebec would prevent the two peoples from ever "coalescing into one body and so extinguishing forever the distinctions between the two races." While Pitt acknowledged that Anglicizing Quebec was the ultimate aim of the legislation, he maintained this would occur once the French inhabitants saw the fundamental fairness of the act and recognized the superiority of English laws. Only then would they renounce their old laws and customs and accept assimilation without bitterness.

Fox passionately pleaded to include in Canada's Constitutional Act provisions that would ensure the greatest possible democracy for the colony. With his swift, penetrating, comprehensive mind, Fox saw the ultimate consequences of a restrictive constitution and he implored his colleagues in the Commons to approve a more liberal constitution for Canada, one consistent with the "enlightened principles of freedom" that were then being widely proposed by Thomas Paine in his new book, The Rights of Man.

Fox declared

In His Own Words"Canada was a country as capable of enjoying political freedom in its utmost extent as any other country on the face of the globe."

Fox believed Canadians should have all the freedoms of the Americans to the south, so that Canadians would have nothing "to look to among their neighbours to excite their envy." He argued "the proposed legislation held out to Canadians something like the shadow of the British Constitution, but denied them its substance."

Fox's arguments fell on deaf ears for Pitt's views prevailed and the legislation passed largely unchanged with substantial majorities in both the House of Commons and the House of Lords. Only two minor revisions were made to the bill's fifty clauses: one reduced the terms of the two assemblies from 7 to 4 years; the other increased membership in Lower Canada's assembly from 30 to 50 members.

The Constitutional Act of 1791 gave what the British government considered the "appropriate rights of Englishmen" to the colonists of Canada. It authorized the creation of two provinces: Lower Canada, because it was down river along the 'lower' part of the St. Lawrence River, and Upper Canada, because it was up the St. Lawrence River. English Common Law was to apply and land tenure was by fee simple. The actual division of Quebec into the two provinces was not accomplished by the Act itself but resulted from an Order-in-Council approved by the British cabinet on August 24th, 1791.

Each new province was to have its own legislature of two chambers. Upper Canada, which was called "the child of the American Revolution," was to have a Legislative Council or Upper House composed of seven members appointed for life by the crown. The Council was designed to exercise a restraint on democracy and foster "Connection, Order, Gradation and Subordination"in society. In other words every person had his or her proper level on the social scale and was expected to remain there. There were leaders and their were followers. The latter were to be those in the lower orders. They were expected to subordinate themselves to the former. Provision was included in the Act for the King to award hereditary titles to members of the Council in order to create a kind of colonial aristocracy which was intended to be the colony's equivalent of Britain's House of Lords.

With wisdom and insight totally lacking in both Burke and Pitt, Fox saw the senselessness of such pioneer peerages and ridiculed the idea of an appointed, aristocratic, legislative council - a kind of second-rate, half-hearted House of Lords in the wild woodland. Fox argued that in a frontier society individuals would succeed or fail on their own talents and toughness. The concept of a colonial nobility would "stink in the nostrils of the natives," and instead of attracting respect would excite only envy and ridicule. History proved him to be right and this provision which was never implemented became a dead letter.

|

|

Sir Eric |

The Legislative Assembly or House of Assembly was the only democratic feature of the 1791 constitution. Its sixteen elected members represented and were responsible to the voting public to whom they had to appeal for re-election every four years on a property franchise. Electors had to be at least 21 years of age and property qualifications were not needed to be elected to the Assembly. As in Britain, legislative councillors and clergymen were not eligible for election to the Assembly. It was required to meet with the Legislative Council at least once in every year. Although the Assembly was a useful mouthpiece for the people it was in the beginning not much more than that for it had little real political power.

The Speakers of both houses were appointed by the lieutenant-governor. The core of the constitution ensured that power remained in the hands of the lieutenant-governor, the Executive Council and the Legislative Council, all of which were completely independent of control by the people.

The governor had the powers of veto and patronage appointments which gave him a great deal of influence. Although most of the positions he awarded did not pay high salaries, the importance his appointing power had on the minds of the official class was considerable, particularly for those who intended to settle permanently in Upper Canada and raise families. These people were always on the lookout for jobs for themselves and for their grown children, jobs that could only be obtained by currying favour with the governor. The governor also had the power to award grants of land in favourable locations and large land holdings when held for speculation were another source of wealth and influence.

The lieutenant-governor was advised and assisted - some said ruled - by a five-member Executive Council, a kind of cabinet, whose members were appointed by the lieutenant-governor. Although the elected House of Assembly alone was empowered to tax the people, the governor was not dependent on the Assembly for money. His control over other sources of revenue made him financially independent of the Assembly. Therefore, whenever he chose he could ignore the will of the people as represented by the popularly elected Assembly. The governor called into session, prorogued and dissolved the legislature. He was empowered to withhold royal assent to any legislation with which he disagreed or he could reserve any bill for consideration by the British government. This veto power could be exercised for up to two years following the date the legislation was approved. This resulted in prolonged period of uncertainty before anyone really knew what the actual status was of any locally approved legislation.

|

|

House of Assembly to Levy Taxes |

One in every seven acres of newly surveyed land was to be set aside as a source of support and maintenance for the Church of England. This church served as handmaiden of the government by indoctrinating the population in the principles of order, deference and sobriety and served as a strong deterent to the "subversive, leveling ideas of the American state and society." Members of this church were expected to safeguard the crown. Known as Clergy Reserves this land became the continuing source of bitter anger and agitation from other church denominations whose members resented this exclusive gift to the Church of England of hundreds of thousands of pounds.

|

|

Reserves Solely for Church of England |

Government policy was to retain both the clergy and crown reserve lands until their value increased enough so that their sale would subsidize the church and the state. Delaying the sale of this land was bad enough but Simcoe worsened the problem by declaring that the reserved lots were to be spread throughout the townships in a "checkerboard" pattern, rather than simply being set aside in large blocks of land. Scattering the reserves in this manner converted what was intended to be a boon into a real bother for the pioneers.

|

|

Checkerboard Pattern |

Despite Simcoe's commitment to the speedy development and his preoccupation with the construction of roads to facilitate the defence and growth of the colony, he failed utterly to see what a serious impediment to the development and settlement of the colony the Clergy and Crown reserves were. These reserves were large plots of primeval forest scattered throughout the province which isolated settlers, provided sanctuaries for wild animals and prevented the establishment of a sound system of roads throughout the colony. This hindered movement and speedy communication for travellers and trade. When asked what most retarded improvement in the province, one farmer from Sandwich near Windsor stated the reason for the poor growth of the colony was the reserves of land set aside for crown and clergy. These "must for a long time keep the country a wilderness, a harbour for wolves and a hindrance to compact and good neighbourhoods." One writer compared the reserves to "rocks in the ocean that glare in the forest unproductive themselves, and a beacon of evil to those who approach them." Revenues from the sale of Clergy Reserves resulted in discontent as other churches spread rapidly throughout the colony and began to demand their share of these revenues. The fight over funds became a political football.

The Quebec bill was debated in the Imperial parliament on May 6th, 11th, 12th and passed on the 16th. It moved quickly through the House of Lords and was signed into law by King George III on June 19th, 1791.

In the temporary absence of Lord Dorchester, the Governor-General of all British North America, who was in England at the time, the Lieutenant-governor of Lower Canada, Major-general Alured Clarke, proclaimed in Quebec City that the Constitutional Act would come into force on the 26th of December, 1791. The proclamation was celebrated with picnics and parties and greeted by 'old' and 'new' subjects alike with wild enthusiasm and great expectations for democracy and economic growth. A popular toast of the time was, "Let liberty extend as far as Hudson Bay and strike a mortal blow at prejudices contrary to civil and religious freedom and to trade."

Celebrations proved to be premature for the constitution concealed a contradiction. Its purpose was to restrict colonists from straying, not free them from external controls. As far as the British government was concerned Canadians were to be kept in their places and democratic heresies were to be confined to south of the border.

|

The Act did ensure that local taxation was to be left "to the wisdom of the people's own legislatures," for the British government had learned one lesson from the American revolution: no taxation without representation.

Pitt's policy was

In His Own Words

"to let the sovereign authority of Britain over the colonies be asserted in as strong terms as can be devised and made to extend to every point of legislation and the exercise of every power whatsoever except that of taking money out of their pockets without their consent." Pitt failed to observe the wise counsel of Edmund Burke who early in his career said, "Liberty is a good to be improved, not an evil to be lessened."

John Graves Simcoe, Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada, described the Constitutional Act as the Magna Carta under which Canadians would be "admitted to all the privileges Englishmen enjoy." A society would be created, he said, that would be "the very image and transcript" of Mother England with all its pomp and peerage. Canadian historian Goldwin Smith had this to say about the constitution: "Though this constitution might be the express image in form it was far from being the express image in reality of Parliamentary Government as it existed in Great Britain at the time. The imitation was somewhat like the Chinese imitation of the steam-vessel: exact in everything except the steam." Democracy came to the United States like an explosion in a great burst of excitement and enthusiasm. In Canada growth of democracy was gradual,taking place slowly over time and coming after some turmoil and without much fuss or fanfare.

|

As long as Upper Canadians were preoccupied clearing land, establishing homes and struggling simply to survive the system of rule by the privileged few was not an issue of real importance to most people. However as time passed and citizens became more conscious of the shortcomings in their society, they began to question privileged control of political power and tensions began to develop.

|

Because the Constitutional Act introduced representative not responsible government, it had within it the disease of its own decay. As a result it became obsolete almost as soon as the ink on it was dry. It was clear from the beginning that the colonists' commitment to the mother country and their support for the colony's administration were tempered by their frontier features and their dual heritage - British and North American. This was an attitude which Simcoe and his successors neither shared nor understood. Because they were from different worlds, the two were eventually torn by tensions. Clashes between the English and the French in Lower Canada and general discord in both colonies persisted resulting on one long period of petitions for redress.

Despite its inherent weaknesses the Constitutional Act for the time being was a start on the road to constitutional development. It provided a political framework within which the colonies could grow. Given free land and supplies to tide them over the tough times, the settlers under the protection of British troops could establish a new life in a new land. Migration of people into the province gave birth to the Constitutional Act. Later settlement resulted in its demise and led eventually to responsible government.

In the interim period the fertile fields of Upper Canada produced bountiful yields of crops along with solid citizens who had forests to fell, dwellings to build and families to raise in this great new land that called Canada.

|

According to Jean Charest, Premier of Quebec,

In His Own Words

"Canadians made a decision very early in their history, a choice that over time has come to define the very essence of who we are. Our ancestors decided right from the start to build a country based on the right to speak a different language, to pray in a different way, to apply a different legal system based on the French Civil Code, to belong to a different culture and to enable that culture to flourish. The Quebec Act of 1774 passed into law more than 200 years ago and almost a hundred years before Confederation is in this respect the most fundamental document in Canadian history. It is the foundation upon which the Canadian partnership was originally built. Its spirit defined this country from its very inception. It represents one of the most enlightened decisions ever made for Canada. Canadians should reflect upon this choice that was made so early in our history. We should reflect on how it defines us, how the French language and culture and the presence in the federation of a French-speaking province has allowed Canadians as a whole to extend their influence and play a greater role in the world community."

Copyright © 2013 Website Administrator