foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

CONFEDERATION & STATUTE OF WESTMINSTER & CONSTITUTIONAL ACT 1982

Canadian history is a study in political survival.

"Of all great subjects much remains to be said."

Walter Bagehot

The Provinces of Upper and Lower Canada ceased to exist in 1841 but the communities of Ontario and Quebec did not. Renamed Canada West and Canada East when the United Province of Canada was formed in that year. It had the same governmental structure as the two Canadas had had: a governor and executive council, an appointed legislative council and an elected legislative assembly. Both provinces were given equal numbers of representatives in the new united assembly. This was done to ensure the English-speaking province, which in 1841 was fewer people than the French-speaking population, had an equal voice in all government decisions. The union worked well enough for ten years because the Reform supporters in both Canada West and Canada East shared a common objective: responsible government. Once responsible government was achieved in 1849 French- and English-speaking Canadians began to diverge.

Until the early 1850s Canada West had the smaller population and so was quite satisfied with equal representation in the Assembly. However, as soon as the population of Canada West began to exceed that of Canada East, some English-speaking Canadians began to demand representaion according to population or "rep by pop." French-speaking Canadians saw this as an attempt by Canada West to take control of the union and vigorously opposed any change in representation based on population.

The legislative union that joined the Canadas was a system of central government in which one parliament made all the laws for both peoples - English-speaking and French-speaking. It became unworkable because it tried to force them both into a common mould, to make them alike in every detail of their lives. French legislators would not be ruled by English in the things nearest to their hearts; nor would English be ruled by French. They fought each other and blocked each other because they were determined to hold the things they loved. However, they shared this land and their hopes lay here together.

When John A. Macdonald won leadership of the Reform party in Canada West, he worked closely with George Etienne Cartier, the leader of the reform party in Canada East. Both men attempted to make the union work and the Macdonald-Cartier government formed in 1854 did manage to function satisfactorily for a time, but sectional problems persisted. The two men could not even agree on a location for the capital. French Canadians wanted Montreal or Quebec while English-speaking Canadians wanted either Kingston or Toronto. The matter was referred to Queen Victoria who chose the lumbering town of Ottawa but the union legislature refused to accept her choice.

The Macdonald-Cartier coalition was driven from power and George Brown's Reformers took office. They failed to find sufficient support and also lost power. This convinced Brown that the union would no longer work and he suggested all parties consider the possibility of federal scheme that would include the Canadas and the Maritime colonies. Macdonald and Cartier agreed and along with Alexander Galt, who was the Macdonald-Cartier Minister of Finance, formed what became known as the Great Coalition. A new hope was stirring amid the wreckage.

Because all union government business was halted by the stalemate a solution was required quickly. The need for speed was answered by some incredibly good luck. Three of the Atlantic provinces had decided to hold a Maritime Conference on Maritime Union on September 1st, 1864 at Charlottetown in Prince Edward Island

|

|

Confederation Chamber ["In the hearts and minds of the delegates in this room was born the Dominion of Canada." |

to consider a union of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island. Members of government of Canada requested permission to attend and were invited to do so "unofficially." On September 1 the Canadian delegation of 8 cabinet ministers including John A. Macdonald, George Brown, George Etienne Cartier, Alexander Galt and D'Arcy McGee arrived at the sleepy town of Charlottetown on the vessel Queen Victoria. There was no one at the dock to greet them. A local Member of the Legislature happened to be there and he commandeered a rowboat and went out to welcome the Canadians. The new arrivals promptly monopolized the meeting. No accord was concluded on Maritime Union, but after much talk and many toasts agreement was reached on the holding of a Confederation Conference at Quebec on October 10th to discuss a wider union of all provinces. The confederation train was on the planning board.

Thirty-two delegates met in the parliament house of historic Quebec on October 10th, 1864. Day after day the delegates from the five colonies talked. After meeting behind closed doors for eighteen days the Quebec Conference broke up having passed a series of 72 Resolutions - the Quebec Resolutions - which laid out a carefully developed plan for a federal union of all British North America.

|

While the concept still had to be approved by each of the five provinces and by the Imperial Parliament, the confederation train was constructed and about to start rolling. D'Arcy McGee, the most eloquent of our Fathers of Confederation in a speech to an audience of Haligonians praised the concept of unification of the colonies and charged that the only objections to the proposed union of the provinces were

In His Own Words"from those who have a vested interest in their own insignificance."

The British government warmly endorsed this initiative and enthusiastically approved the 72 Resolutions. Confederation was not just an internal matter for events were occurring to the south that had a major impact on our country's constitutional considerations. Across the border the American Civil War was raging and at the same time the Canadian conference was taking place soldiers of the Confederate States of America who had come across the border into New Brunswick launched a raid from that colony on St. Albans in Vermont. Americans were outraged by this inflammatory act which the United States regarded this as yet another hostile British act in support of the southern cause and reacted violently. The American government subsequently ended a trading treaty with the British colonies and demanded a passport - something that has recently been revived - for all Canadians travelling to the United States. American enmity towards Britain and her Canadian colonies was reflected also in their attitude regarding confederation. The United States displayed no readiness to acclaim the new nation and instead of extending congratulations, the American Congress passed a resolution expressing outraged disapproval of the very concept of a Canadian federation.

|

Fear of American military and economic aggression was the ever-present prod that persuaded the provinces to consider union for defensive purposes. When the American Civil War ended a million soldiers were demobilized plunging the country into mass unemployment. Irish-Americans were hardest hit by the joblessness and many of them decided to put their military might to use by forming a secret society called Fenians. This group of disgruntled Irishmen pledged to fight for the creation of an independent Irish Republic, something which Britain strongly opposed. Where better to battle Britain, the arch enemy of Irish independence, than in its closest colonies - British North America. As a result a series of frontier raids were carried out at various places along the border as American authorities looked on. These incursions served to persuade the provinces to consider union for purposes of defence. Fear of the Fenians helped eliminate opposition to confederation for the colonial leaders knew that if they had any hope of being able to defend themselves, they needed numbers. Britain strongly supported union of the colonies for defensive purposes and pressed all provinces to participate.

|

New Brunswickers feared a Fenian attack and while it fizzled out, the threat left them with a lasting alarm. [*]

In Upper Canada meanwhile a Fenian force crossed the Niagara River from Buffalo in May, 1866 and invaded the Niagara Peninsula at Fort Erie. They brought an extra supply of arms for any discontented Canadians who might wish to join in the liberation of their country. To the bewilderment of the Fenians no Canadians cared to become a member of their bizarre assemblage. After eating a hearty meal of ham, bread and coffee, compliments of their reluctant hosts, the invaders took a leisurely nap on the shaded lawns of the townsfolk.

|

Refreshed, the Fenians struck out towards Hamilton to conquer the country. They were met en route by a force of Canadian militamen and they clashed at the Battle of Ridgeway. Nine young Canadians died that sunny, spring day in defence of a country to come. They shed their blood for a greater cause than they could ever have imagined. Meanwhile the Fenians decided that discretion was the better part of valour and retreated to Fort Erie from where they hightailed it back across the river to Buffalo.

|

The confederation train was starting to move.

|

The plan for a federal union was ratified with no difficulty in Canada, but reaction elsewhere was different. When Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland decided not to join it was a real disappointment and the confederation train suffered a severe jolt. However, when voters in New Brunswick unexpectedly defeated the party supporting union the train jumped the tracks. This defeat very nearly wrecked the whole concept of confederation because New Brunswick was an essential link between continental Canada and peninsular Nova Scotia. Fortunately a subsequent election in New Brunswick restored the pro-federation party led by Leonard Tilley to power and it promptly opted to approve union. New Brunswick become the fourth province to enter confederation.

Canada (Ontario & Quebec), Nova Scotia and New Brunswick decided the time had come to act and late in 1866 their delegates gathered in London. The mission: to create a new country called the Kingdom of Canada. British officials had reservations about the name 'kingdom' fearing the Americans might object to having a kingdom next door having a few years earlier fought to rid themselves of that name. What they would have done about it was never known because the name of the new nation was changed to Dominion of Canada, a kingdom, in fact, but not in name.

Early in 1867 the British Parliament ratified confederation with the British North America Act, the Constitution Act 1867, which united Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick.

|

|

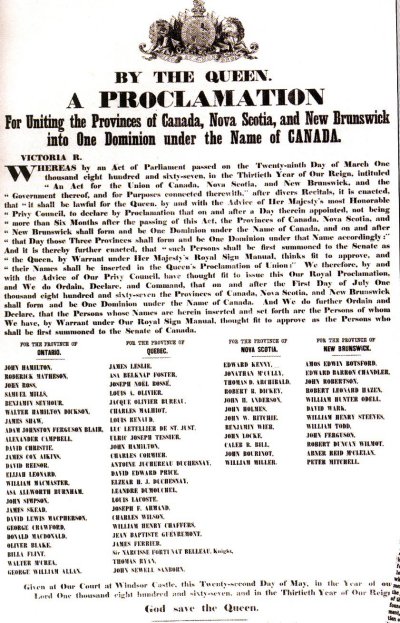

Confederation Proclamation |

At midnight on July 1st, 1867 church bells rang, the thunder of a hundred gun salute filled the air and four million people became Canadians.

|

"With the first dawn of this gladsome midsummer morn, we hail the birthday of a new nationality. A united British America with its four millions of people takes its place this day among the nations of the world. Stamped with a familiar name, the Dominion of Canada on this First day of July, in the year of grace, eighteen hundred and sixty-seven, enters on a new career of national existence." [**]

The confederation train was back on the tracks and chugging along at a very good speed. Manitoba joined confederation in 1870 and the acquisition from the Hudson's Bay Company of Rupert's Land and the North West Territories brought Canada to the Rocky Mountains. With British Columbia's admission in 1871, the Dominion from Sea to Sea to Sea became a reality. Prince Edward Island joined in 1873. The provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan were created in 1905. Newfoundland completed our coast to coast country by joining in 1949.

|

|

Canada's 1st Parliament |

|

|

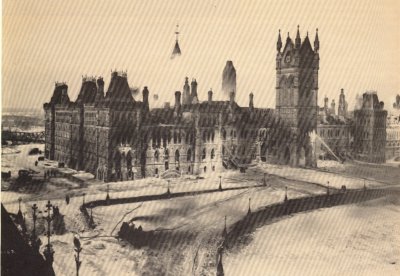

On the evening of Feb. 8, 1916 flames erupted suddenly in the reading room of the House of Commons and fire swept through virtually the whole of the centre block. This photgraph was taken the following morning. |

|

|

Canada's Parliament Buildings |

|

|

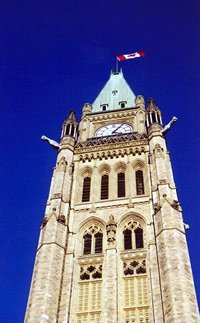

The Peace Tower |

|

|

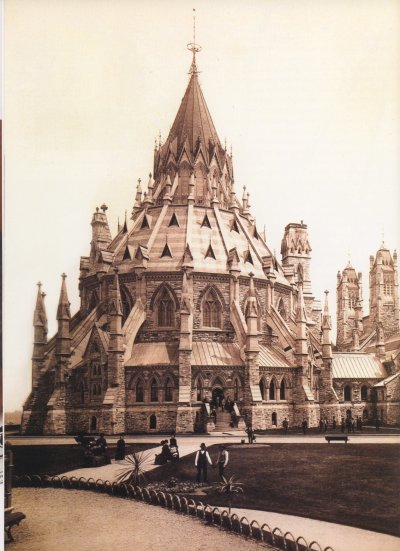

The Parliamentary Library, which was part of the 1st Parliament Buildings, survived the fire of 1916 |

|

|

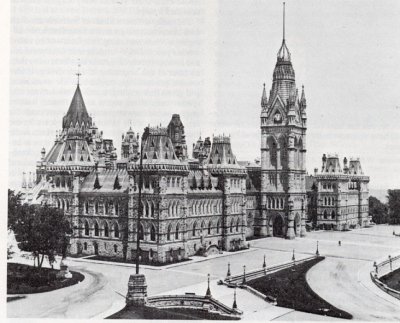

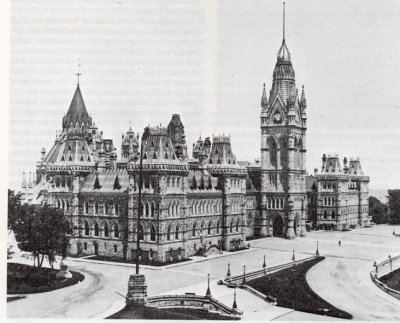

Original Parliament Buildings completed in 1867 and destroyed by fire in 1916 |

|

|

Current Parliament Buildings as rebuilt in 1917 with its grand central tower originally called Victoria Tower but renamed in 1933 the Peace Tower. |

Sir John A. Macdonald became Canada's first prime minister. "At fifty-two he was in the prime of life and at the height of his powers. He was a tall, slight, jaunty figure with dark, curly hair, a big nose, an ugly charm to his face and a genially sardonic smile." Born in 1815 in Scotland, he was brought to Canada in 1820. In 1830 he began the study of law and was called to the bar in 1836. Following the Rebellion of Upper Canada in 1837 in which he served as a a private in the militia he defended in court two of the rebels. He entered public life in 1844 when he was elected as member for Kingston in the provincial legislature. In 1864 when convinced the hour had come for confederation "he rose at once to the height of his great opportunity, and during the next three years of negotiations with recalcitrant supporters, with hesitating sister provinces and with the mother country, he displayed a skill that by comparison, dwarfed the efforts of any of his colleagues." He attended the Charlottetown, Quebec and Westminster Conferences. He skill, patience and tact were critical in steering the Confederation resolutions through the Legislature. In 1867 he became our country's first prime minister.

|

|

Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald |

Contention continued to accompany our constitutional development and it was not confined solely to our own shores. Britain, the Mother Country, was intimately involved in the stresses and strains of our political growth and shared at the official level some of the exasperation if not the exhilaration along the road to our independence.

In 1931 the Statute of Westminster brought us to the brink of nationhood. Its approval was controversial and occurred in an atmosphere charged with emotion. The enactment of the statute was greeted by some in England with irritation, anger and outright opposition. The strong opinions and passionate arguments which accompanied the birth of this statute some seventy years ago make interesting reading in light of our ongoing preoccupation with the constitution.

The first reference to the bill that eventually became the Statute of Westminster was made by King George V in his Speech From the Throne given at the opening of the British Parliament at noon on Tuesday, November 10, 1931. It appeared insignificantly enough as the sixth of fourteen paragraphs in that Speech which according to the newspaper The Times occupied little time in its delivery.

The King read the Speech "in a voice that was clear and resonant which every one could hear." "In conformity with the undertaking given to the representatives of my Dominions in 1930 a measure will be laid before you to give statutory effect to certain of the Declarations and Resolutions of the Imperial conferences of 1926 and 1930. This measure is designed to make clear the powers of the Dominion Parliaments and to promote the spirit of free cooperation among members of the British Commonwealth of Nations."

|

|

George V |

England like the rest of the world at that time was preoccupied with serious economic problems for the world was in the depths of the depression. Some British parliamentarians thought it unfortunate that this legislation should occupy Parliament's time and attention when other "paramount matters are pressing on the public's mind." In spite of these more urgent demands the innocuous sounding legislation did go forward but it was not unnoticed.

It had all started at the Imperial conference of 1926 where James Arthur Balfour, the chairman of the conference, had written on a half sheet of paper the objective of all those in attendance.

In His Own Words"Equality of status as between the Dominions and ourselves [i.e. Great Britain] and as between each other."

Five years later seven lawyers took the better part of three months to convert this simple statement of intent into legislation. Its detractors said it was "so saturated with law and so technical in its import that no one but a lawyer would be expected to grasp its full significance." Predictably this legislation was greeted with outraged ridicule by those who wanted no changes in Britain's status as the sole keeper of the keys of the kingdom. The legislation was considered by some to be completely unnecessary and what was even more menacing it was thought to have the potential to create division among members of the Empire and possibly even eliminate "the long-lasting ties of blood and sentiment" existing between the Dominions and England. Lord Salisbury said he did not think

In His Own Words"there ever was a measure proposed to Parliament, the country and the Empire which was received with so little enthusiasm. The Dominions were after all practically free, the word 'free' being the word he preferred to 'independent.'

Speakers at a meeting of the Royal Empire Society were outraged at the proposed legislation which they said threatened the very existence of the Empire. Lord Atkin stated that its effect would be to put the Imperial Constitution on the "chopping-block" and "cut off the limbs of the Constitution and leave no unity at all."

|

He strongly believed that it was important on occasion for action to be taken in London that affected all the countries of Empire (that is Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, etc.) and that enactment of this Statute of Westminster (he called it a preposterous proposal) would cut away the only means of ever taking such action. Another speaker said he deplored the statute and was perfectly certain if it were passed that it would not work. A third speaker gravely expressed the view "that the Statute of Westminster and all that it implies marks the parting of the ways."

The only sane and supportive voice seemed to come from Lord Stonehaven who condemned all the fretting and fuming over the legislation. He declared that if nothing more happened to the Empire than the passage of the Statute of Westminster, then "they could all rest quietly in their beds." In attendance that evening at the Royal Empire Club meeting was Canada's High Commissioner to the United Kingdom, Mr. G. Howard Ferguson. His opinions on the Statute of Westminster and the highly reactionary rantings it raised were not recorded. No doubt he simply wanted it to pass as quickly as possible.

The Times in an editorial on November 11th headed, "Inevitable Pedantry," noted imperiously:"It is not a measure which anyone but pedants of Dominion status will regard with any enthusiasm. The Dominions have grown to full manhood. By this Statute the last shadowy grievance of pedantic sticklers for formal political equality will be removed and the way will be cleared for building up a new unity on the basis of free and unfettered cooperation." The paper then quoted Lord Buckmaster of the House of Lords who said he could see no reason for putting into the formality and obscurity of an Act of Parliament an agreement which worked well and which everybody accepted as it was.

It was charged that only two among the six Dominions had "persistently and perhaps rather combatively" agitated for the change the Bill was designed to bring about. One of these 'combative' dominions was Canada which was foremost among the "pedantic sticklers" pressing for the legislation. According to The Times, "Canada had approved the Statute in its parliament without a dissentient voice," while two other dominions had approved the bill "though not so boisterously." Australia had only approved it with considerable misgiving and New Zealand had "acquiesced but with an air of detachment if not to say a positive distaste."

Winston Churchill was one of a number of British politicians who had reservations about the legislation. He feared with its passage "the needless obliteration of old famous landmarks and signposts which though archaic had historic importance and value." Nevertheless, he conceded,

In His Own Words"If large numbers of our fellow-subjects in the Dominions liked to think and liked to see in print that the bonds of Empire rested only upon tradition, good will and good sense, it was not our policy or in our interest to gainsay them. We have every respect for the wishes of the Dominions and are always ready to defer to their desires. Still the Mother Country must have wishes and points of view of its own, and I can not believe that they might not be accepted with equal good will in the family circle of the Empire or if the word 'Empire' were objected to, in the family of the British Commonwealth of Nations."

According to Hansard, the name given to the official record of what is said and done in Parliament, cheers greeted these comments. The Mother Country's 'wishes' to which Churchill referred pertained to certain amendments to the Statute that he and some other English parliamentarians wanted to apply only to the Irish Free State. Wiser heads prevailed, however, because the Members realized the very serious effect which would result on the future of Imperial relations from any "light-hearted handling of what is admittedly a pedantic, but in all the circumstances an inevitable piece of legislation." In other words the Dominions wanted this enacted as it was and so they had better enact it. No significant changes were made in the Statute and the bill with received third reading in the House of Commons on November 24th by a vote of 350 to 50. It was sent to the House of Lords where it was approved un-amended on December 2nd. The King gave it Royal Assent given shortly thereafter. "Britain," explained one politician, was like "the parent of a healthy family and as with many parents had found it difficult to recognize that her children had grown to manhood. She had, therefore, given them the latchkey but reserved the right to bolt the door."

|

The Statute of Westminster removed all legislative authority the British Parliament had over Canada with the one exception. Because Canadian politicians were unable to agree to the formula to be used to amend our own constitution, they left things as they were. This meant that when we as a country wished to amend our constitution, we had to request that it be done by the British Parliament. This meant that Canada was not a fully autonomous nation since it could not amend its own constitution. In that one sense, therefore, Canada remained a colony for another fifty-one years.

Thanks largely to the determination and dedicated efforts of Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, Canada's constitutional development was fully completed in March, 1982 when our constitution was finally brought home. In its last legislative act affecting Canada the British Parliament "held its nose" and passed the Canada Bill which patriated (brought home) our constitution along with a charter of fundamental human rights - what is now known as the Charter of Rights and Freedoms (Sections 1-34).

The Supreme Court of Canada unanimously declared

In Their Own Words"that the charter is the supreme law of Canada and is a new yardstick of reconciliation between the individual and the community."

Included in the Constitution is the Canadian amending formula which permits us to change our constitution. Changes can be made to the constitution if the changes are agreed to by at least 7 provinces having within them at least 50% of country's population. This amending formula also includes what is called the "notwithstanding clause." This is a kind of 'escape' clause which when invoked permits the federal or any of the provincial governments to declare any law they make - which might otherwise be challenged in court because it over-rides the Charter - to be exempt from provisions of the Charter. (section 33) This exemption can be renewed every five years if so desired.

For the very first time the Constitution of Canada formally mentions the existence of the office of prime minister. No other Act explicitly mentions this office.

The Canada Bill was given royal assent (proclaimed into law) in Ottawa by Queen Elizabeth on April 17, 1982 when it was signed by the Prime Minister and the Queen on the steps of our Parliament Buildings. This year marks the 23rd anniversary of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. The Constitution Act 1982 is one of the great legacies of the leadership of the late Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau who overcame considerable opposition from various parts of the country in order to patriate our constitution and make us in fact as well as in form an independent nation. Because of his determination, drive and direction Pierre Trudeau joins the Fathers of Confederation in having laid the foundations of our country and shaped its greatness.

. |

|

Fenian John O'Mahony |

[*]John O'Mahony, the 19th-century founder of the Fenian rebel movement and the would-be conqueror of Canada is to be honoured as a hero of Irish nationalism this month at his Dublin gravesite 140 years after his failed 1866 invasion of New Brunswick. A terrorist in the eyes of British and Canadian officials of the day, O'Mahony will be hailed at a May 28th anniversary ceremony as in "inspirational force" in the fight that long after his death in 1877 led to the creation of the Republic of Ireland. In Canada O'Mahony is best remembered as a blundering rebel and an accidental 'Father of Confederation'. [National Post, May 6, 2006] [**] This excerpt is taken from the editorial in The Globe dated July 1, 1867 and was written by George Brown, the founder, owner and editor of this paper, the predecessor of today's Globe and Mail.

Copyright © 2013 Website Administrator