foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

LOSING ABORIGINAL LANDS

History is the organized story of the whole human past.

The imperial conquest of North America began when the French founded Quebec on the St. Lawrence in 1604, the English settled on the James River in 1607, the Spaniards established Santa Fe on the Rio Grande in 1609 and the Dutch built Fort Nassau on the Hudson River in 1614. Initially Europeans were vastly outmanned by the numbers of Native warriors who could easily have overwhelmed the woebegone whites in no time at all. Why did they not do so? The reasons are varied.

Natives failed to feel threatened by the small bands of whites who came to trade or till on coasts and rivers. For the furs and skins they sought they brought boons such as muskets, iron tools, useful or novelty knickknacks and liquor. Whites concentrated around fortified villages and were well supported by seapower and firearms. Once settlers had consolidated their positions they fought tenaciously to hold their ground, while Natives rather than persevere and fight fiercely simply withdrew further inland. Once established the seemingly inexhaustible flow of white settlers from national sources stood in stark contrast to limited number of Natives scattered across the forested frontier. Their effectiveness was crippled by tribal feuds and their failure to join forces. Finally and most fatally whites brought with them 'invisible battalions,' infectious diseases like influenza, chicken pox, smallpox, measles and plague against which Native Americans had no genetic immunity and were decimated.

"When your white children first came to this country, they did not come shouting the war cry and seeking to wrest this land from us. They told us they came as friends to smoke the pipe of peace; they sought our friendship; we became brothers. Their enemies were ours. At that time we were strong and powerful, while they were few and weak. But did we oppress them or wrong them? No! Time wore on and you have become a great people, whilst we have melted away like snow beneath an April sun, our strength is wasted, our countless warriors dead." Shinguacouse (Ojibwa Chief) 1849)

Most colonists did not come to America intent on killing, enslaving, converting or consorting with Native Americans. They simply expected them to make way for the whites. The attitude of most whites regarding the Aboriginals was summed up by a British Member of Parliament at the commencement of the Seven Years' War. "Here is a contest between two equals about a country where both claim an undivided right. I think it is allowed on all hands that the Natives have no rights at all."

Even the urge to redeem with religion and bring civility to the Aboriginals faded before the settlers rapidly multiplying numbers and insatiable appetite for land. While politicians sitting safe and secure in London saw Native warriors as potential military manpower made necessary because of their own persistent shortage of regular soldiers, settlers seeking ever more land saw the Natives as obstacles to be feared, fought and dispersed.

The end of the Seven Years' War with the fall of Quebec and the ensuing Treaty of Paris in 1763 changed everything for the Native Nations. It eliminated the English-French competition in the fur trade as the French abandoned the continent ceding to Great Britain all their lands in Canada and east of the Mississippi and turning over New Orleans and the Louisiana territory west of the Mississippi to Spain which yielded Florida to Britain. No longer able to find a strategic middle ground by playing contending European powers against one another, the tribes were left with few options. Instead of dealing with the French who wanted their trade but not their land, the Native peoples were confronted by a never-ending flood of settlers and their settlements advancing from the east. Most disturbing to the western Indians was the influx of settlers from the coastal colonies into the Ohio Valley. The French had come into that area as traders dependant upon Natives for furs. Now English colonists came as settlers and displaced the Aboriginals.

In the Ohio Valley the Delawares and the Shawnees lashed out against their enemies - both whites and rival tribes - who had driven them from their original homes in the east. In response Lord Jeffrey Amherst enforced a repressive Native policy that included authorizing distributing among them blankets infected with smallpox. This resulted in the bloody rebellion led by Pontiac, the chief of the Ottawas, who was successful in welding a coalition of Aboriginal tribes south of the Great Lakes and east of the Mississippi in a united resistance against the encroaching English settlers. Their assaults against the British posts were so effective that most of them fell and by the summer of 1763 more than 2000 settlers had been killed and their settlements ravaged. Although the outbreak was eventually crushed the British government regularly feared a renewal of Indian Wars and acted to prevent them.

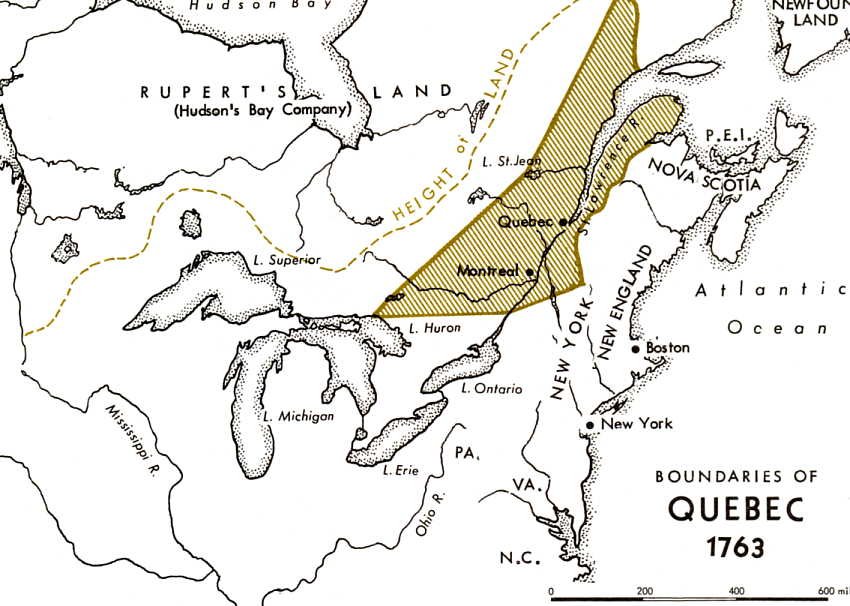

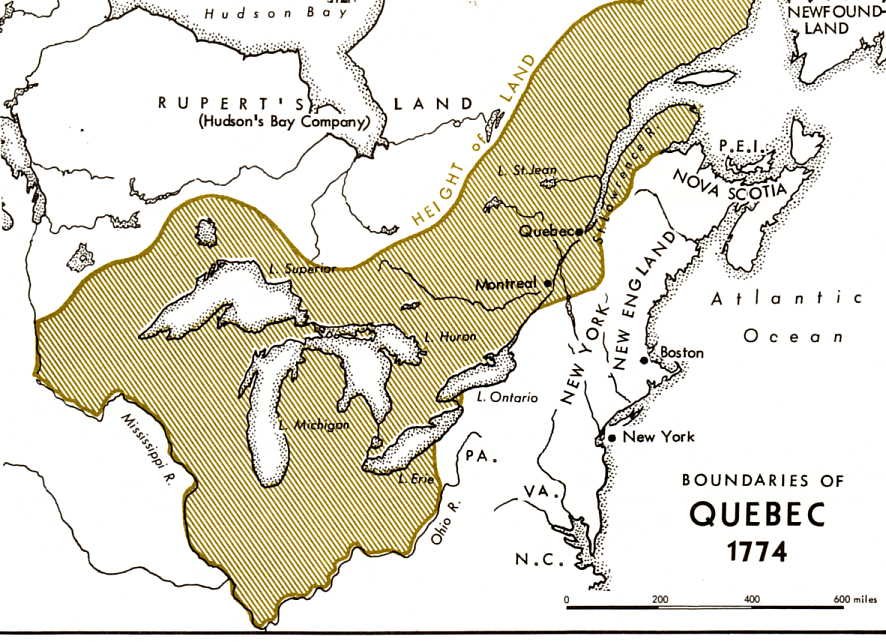

In an attempt to buffer the Aboriginals from the whites and restrain land speculators and settlers from establishing breakaway colonies, King George III signed the Royal Proclamation of 1763 which drew a line down the crest of the Appalachians and declared settlement west of it off limits. It was hoped the Proclamation would enact a policy of pacification of the western Native tribes. It established an enlarged boundary for the colony of Quebec, the new name for New France. This was followed by the Quebec Act of 1774.(see maps) It was hoped these acts would halt westward expansion, secure land for the Natives and provide a buffer between Upper Canada and the 13 Colonies.The acts aroused nothing but frustration and bitterness in the 13 Colonies for they denied Americans access to the great, open western spaces in which they say their future. The resulting resentment and anger became one of the major causes of the American revolution.

|

|

Royal Proclamation of 1763 |

|

|

Quebec Act 1774 |

In a relatively short period of time the Aboriginals had lost nearly all of their Atlantic homelands, the territory south of the St. Lawrence River and most of present-day southern Ontario. Few colonists took the Proclamation as anything other than a temporary delay in their inexorable march across the mountains. The single most important reason for this rapid change was the American War of Independence and the Loyalist migration to British North America resulting therefrom.

In 1794 times were tense in Upper Canada and a major reason was the unrest of Native tribes in the Northwest Territory because of the encroachment of Americans on Aboriginal lands. From George Washington's time onward, Americans used every opportunity to thrust the Native tribes westward in their relentless urge to acquire ever more land. Native peoples were pressed unrelentingly to abandon their homes and heritage in the face of the insatiable search for land in the west. While some saw the warring Aboriginals as brutal villains, others saw them as misunderstood victims. Even Washington, who acquired for himself fine fertile farmland and encouraged and supported this expansionism, recognized that Native violence was the result of white colonists and their inroads into indigenous lands. "The Indian side of the story would never make it into the history books

Robert Hamilton, a wealthy merchant in Upper Canada, remarked on this American longing for western lands in a letter to Governor Simcoe dated January 4th, 1792.

In His Own Words

"The Americans seem possessed with a species of mania for getting lands which has no bounds. Their Congress, prudent, reasonable and wise in other matters, in this seems as much infected as the people."

While the Natives could not stem the flood of white newcomers who multiplied at a staggering rate, they responded to the onslaught with hatchet and flame. In addition to set-piece conflicts, the risk of skirmish, ambush and death was an ever-present fact of life for both whites and Natives. American attacks on Native settlements resulted in retaliatory raids on white squatters. The American squatters attributed much of this mayhem to the subversive activities of British Indian agents urging on the Aboriginals and keeping them well supplied with guns, ammunition and war paint. They conveniently ignored their own cavalier contempt for boundary treaties that had been solemnly signed by their leaders and the sachems.

In addition to being charged with fostering frontier fighting in the west, the British were faulted for their failure to relinquish following the American Revolution the northwestern posts which were all located on American territory. These irritants festered in the minds of Americans and as terror and tensions grew it became clear to many that the two countries were poised on the brink of war. During these tense periods between the two countries, each sought alliances with Native warriors. Both vied for the allegiance of the various tribes and spared neither energy nor expense to win them over. In New York this included paying a dollar a head to Iroquois braves who were invited aboard a French ship to see the guillotined semblance of Louis XVI's severed head dripping blood. Both countries contrived in every way they could to create jealousies and divide Native loyalties. Washington bemoaned the British success in this regard and charged them with,

In His Own Words

"Seducing tribes that we have hitherto been keeping at peace at a heavy expense and who have no cause for complaint."

Britain was fortunate to have Joseph Brant's leadership to thank for keeping the Six Nations true to the King's cause. Despite Britain's friendship with Brant and the tribes of the Six Nations, William Johnson, British Superintendent of Indian Affairs, admitted that fair and equitable treatment of the Aboriginals was difficult to ensure because it frequently conflicted with the interests of leading men in the province. Merchants with investments in land speculation as well as local sheriffs and justices of the peace hindered government efforts to secure just treatment for the Aboriginals. This usually involved land deals.

Although land was bought and treaties were signed by British officials, the deals were often defined in the vaguest of terms. For example, northern boundaries were determined by how far a person could walk in a day or by how far one could hear the sound of a gun fired from the lakeshore. The First Nations received very little for the immense tracts of land they ceded. In 1784 the Mississaugas gave up 3 million arcres along the Niagara Pensinsula for less than 1200 pounds worth of gifts. British negotiators were always cautioned "to pay the utmost attention to Economy." Treatment of the Natives was often tawdry too. Charles II was advised to bestow on the "Indian kings" who needed wooing, "small crowns or coronets made of thin silver plate, guilt and adorned false stones."

The increasing loss of their land to white settlers was a source of continuing concern to the chiefs of the various tribes. They were aware of the ongoing negotiations between the American John Jay and his British counterpart and eagerly awaited the terms of the treaty hoping it would include provisions that would protect them and their lands from further encroachment by whitemen. They waited in vain for while the treaty referred to Aboriginal trade, it omitted any mention of Aboriginal property rights. The Natives had backed the losing side and were now at the mercy of whites on both sides of the border. Many tribes saw the extinction of their way of life "written on the wind."

While they readily admitted that Native warriors had bled freely for the King, the British proceeded to sacrifice the interests of their Native allies to the cause of accommodation with the Americans. If the Aboriginals intended to confront Americans to preserve what was left of their lands, they would simply have to shift and shoot for themselves. In the United States an important source of government revenues came from the sale of land to settlers, land which had been purchased for a pittance from the Aboriginal owners. Americans were shocked when they began to realize that increasingly tribal chiefs were becoming less willing to sell their lands to scheming individuals for mere baubles and beads. "It is no secret that the Indians are beginning to appreciate their lands, not so much for the use they make of them as by the value at which they see them estimated by those who purchase them."

As the acquisition of land from the Aboriginals became more complicated and costly, it resulted in American government agents making deals fraudulently with renegade representatives of the tribes or bribing chiefs with dollars and drink to get them to make their mark on official documents. Often land speculators simply claimed Aboriginal lands before government agents had completed their negotiations and then provoked the Natives to do something about it. When warriors responded with force to protect what was theirs the army was called in to "rescue" American interlopers. Defeat usually followed and the chiefs were forced with punitive treaties to sign away their lands. This pathetic pattern was repeated throughout the period of American's westward expansion.

"The Indians should be made to smart," declared the American general Arthur St. Clair. Congress agreed and appropriated a million dollars for a federal army to fight the western tribes. St. Clair marched to the Wabash River southwest of Lake Erie where he met and was badly beaten by a force of Shawnees and Miamis. This convinced the American government that the union of the western tribes had become too powerful to ignore and stronger forces would be required. Prior to using greater military measures half-hearted negotiations usually preceded the use of force to convince public opinion at home and abroad as Jefferson put it,

In His Own Words"that Peace was unattainable on terms the Indians would agree to.",/p>

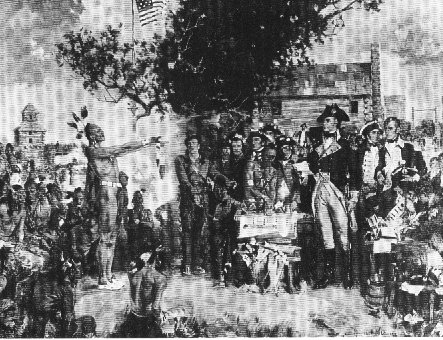

When an important peace parley failed American commissioners sent a coded message to a waiting general."We did not effect peace." The general translated this into "Begin vigorous offensive action." This occurred at a place called Fallen Timbers on August 20th, 1794 when the army of Major-General Anthony Wayne met and defeated a large number of western warriors. Subsequent to this defeat some 110 chiefs and warriors signed the Treaty of Fort Greenville in August 1795. By this treaty, the most important Indian treaty in the history of the United States, the sachems and War Chiefs gave away 25,000 square miles which today includes most of Ohio, part of Indiana and the sites of Detroit, Chicago and a number of other mid-western cities for 25,000 dollars in trade goods - calico shirts, farm tools, trade hatchets, ribbons, combs, mirrors, and blankets and an annuity of $9500 to be divided among the tribes. It was a humilitating settlement with payments that were a pittance. Some tribes received as little as $500 a year. Few could challenge its terms for when Wayne destroyed their fields many became dependent on the United States for food. When a calumet or peace pipe was smoked by the parties to cement the terms of the treaty the ceremony was ridiculed by one American negotiator as "a tedious routine."

|

|

Treaty of Fort Greenville |

From a pre-contact population in the millions the number of Native peoples remaining by 1900 numbered some 250 thousand. Their dispossession makes melancholy reading. The grim truth was that when two peoples competed for the same land the stronger prevailed and the weaker simply had to accept whatever terms they could get. In return for this huge tract of the fertile frontier, pledges were given that the remaining lands would be left to the Native owners. It was not to be for the tide of white settlement was unstoppable.

Joseph Brant, Chief of the Six Nations, hoped it might not be too late to salvage something.

In His Own Words

"I know that to complain of what is past will not ensure an absolute redress but I believe it may be useful to reflect upon past errors and to discuss the malconduct of public officers whereby important injuries have been done to Indians."

Chief Cornplanter thought it was already too late.

In His Own Words

"Brothers, we have scarcely place left to spread our blankets. You have taken our country."

Alone among the sachems the great Shawnee Chief, Tecumseh, refused to sign the treaty. Tecumseh, who was always merciful toward his captives, was a man of remarkable intelligence and ability. Noble in speech and behaviour this great orator was brave and farsighted.

In His Own Words

"So live your life that fear of death can never enter your heart. Seek to make your life long and its purpose in the service of your people. Show respect to all people and grovel to none. When you rise in the morning give thanks for the joy of living.

Tecumseh raged against the sale of lands long held by the Aboriginals. "Sell a country! Why not sell the air, the clouds, the great sea as well as the earth? Did not the Great Spirit make all for the use of his children? Our fathers from their tombs reproach us. I hear them wailing in the winds. We are determined to defend our land, and if it be the Creator's will, we wish to leave our bones upon it."

|

|

Tecumseh at the Battle of The Thames |

Tecumseh did just that. With painted face and tomahawk held high, he fell fighting from a load of buckshot in the breast near Moraviantown at the Battle of Thames. So died one very brave heart. As sunset faded into darkness his faithful warriors stole like spirits through the woods and bore his body away. His people revered him as the white men revered Brock, but their grieving saw no flags lowered, no martial music mourned his death, no stately monument marked his final resting place. They buried him stealthily by the light of flickering torches, his grave quickly blanketed by the falling autumn leaves lost forever in the mists of time.

With the Treaty of Paris in 1763 Native people living near the borderlands of the Thirteen Colonies came under British jurisdiction. Shortly thereafter the American Revolution led to the exodus of Amerindian and white Loyalists into Ontario. To secure lands for these settlers the Imperial government initiated a process whereby the Natives surrendered most of their territory to the Crown in return for some form of compensation. With the Amerindians' loss of their land came the loss of their former fishing, hunting and gathering grounds. They received in exchange land that became known as Indian reserves.

Copyright © 2013 Website Administrator