Foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

EASTERN WOODLAND INDIANS & THE COMING OF THE EUROPEANS

History brings us tidings of antiquity.

Since the World Began

"Like fireflies they glimmered for a moment before disappearing into the dark forest of unrecorded history."

In the most primitive geophysical sense, this country was formed 3.5 billion years ago of Precambrian granite. After the last glacier retreated, the land was garnished with grasses and forests, that crept north across the rock.

No part of Canada has ever had an original population. For thousands of centuries after the earth's crust formed the physical features that comprise Canada, not a living soul trekked across that vast territory. It was terra nullis (empty land). The lonely wastes awaited the arrival of Aborigines - ab origine) (from the beginning) who spread across this empty land at the end of the last Ice Age.

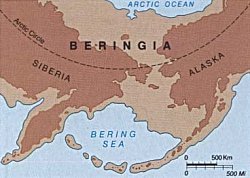

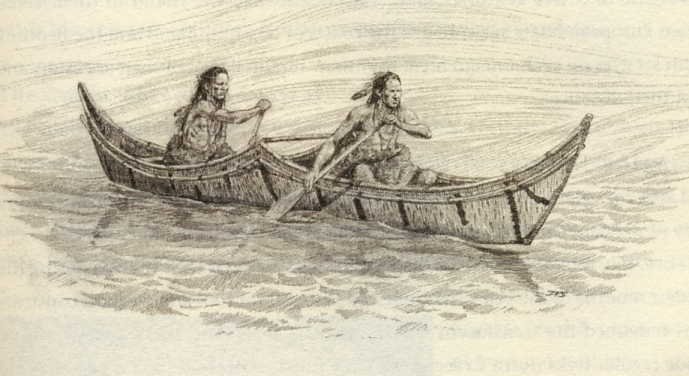

Canada is a land of immigrants, with some coming very much earlier than others. Archeological findings indicate that the Paleoindians, the first immigrants coming from the mists of Asia are ancestors of our Native people. They almost surely fled the hazards of the Ice Age on foot 13,000 years ago at the tail end of the Ice Age. Because the sheets of polar ice locked up huge amounts of water, sea levels around the world fell about three hundred feet. The shallow Bering Strait became a wide plain stretching between Siberia and Alaska and it was called Beringia. In theory, paleo-Indians, as they are known, simply walked across land that was exposed when sea levels were much lower. They crossed the Bering Land Bridge into the uninhabited continent we call North America.

The Alaskan corridor from Old to New World has often been called a land 'bridge', but this is something of a misnomer, for the area left high and dry measured more than 1300 kilometres at its widest and offered opportunity in a cold tundra-steppe environment for generations of animals and humans to cross it. These nomads driven by tribal wars, poor hunting or, perhaps, simply a wish to see the other side crossed over the bridge in waves. The new arrivals moved either eastward along rivers and through passes to the east flanks of the Rocky Mountains or southward along the coast. Both routes led through tundra, boreal forest, deciduous forest, prairie, and desert and other environments like today's.

|

|

Beringia (light coloured sections) |

|

|

Christopher Columbus points the way to the 'New World'. |

Columbus reached islands in the Caribbean in 1492 and therefore was the first European to discover what became America. When we speak of Christopher Columbus discovering America, however, we should be more precise and say he discovered it as a European. In fact, it had been 'discovered' long before his arrival and had been widely occupied by millions of human beings for untold ages. As indicated above, these early men and women had fled the hazards of the Ice Age and crossed the Bering Land Bridge onto the uninhabited continent we now know as North America. These people of Asiatic origin called the continent their own and developed a number of highly evolved native American societies. For them the settling of North America was an epic written in the blood and sweat of ordinary people, men, women and children. Like all epics, it originated with the oral tradition, tales told around the campfire in the language of Native braves.

America owes its name to Amerigo Vespucci, a Florentine, who made four voyages to the new world. The first was in 1499, when he reached the mouth of the Amazon River and explored the coast of South America. He recognized that this land was not Asia, as Columbus had thought, but a new continent. His letters back home about his travels and the people he encountered became very popular and were read widely throughtout Europe. Gradually, over time his name became associated with this new land and led to its being called America after his Christian name.

|

|

Amerigo Vespucci |

While Christopher did not discover this 'new land', he did designate its people with the name Indian for he thought he had reached India. The First Nation's people of Canada dislike this name and the only connection they have with it now relates to the Federal government's Indian Act. Interestingly, when we were in New York attending a genealogical conference, we met and spoke with some American Indians. I asked them how they felt about the name. Those I spoke with were surprised by the question and said they had no problem with it. It had no negative connotations as far as they were concerned and they said feeling was common to all other Ameican Indians.

."Indians swarmed over the continents and islands from the Arctic to Tierra del Fuego, creating communities, establishing networks of trails and trade and adapting the land everywhere to human purposes. European invasion destroyed and brought on a Dark Age for the native peoples, who were cursed by their conquerors as savages and heathens. A maxim among historians says that the conqueror writes the history. True to this adage, European conquerors praised themselves for bringing civilization and salvation to the Americas." The Founders of America by Francis Jennings

Some researchers now believe that the New World was occupied earlier by a single small group that crossed the Bering Strait some 20,000 years ago, got stuck on the Alaska side and gradually ambled across the rest of the Americas in two or three separate groups. The ancestors of most modern Indians made up the second group. Archeologists supporting this view suggest these first Americans must have arrived 20,000 years ago when the ice pack was smaller. Today's Indians are seen as relative late-comers. Indian activists dislike this line of reason, for they say it infers they are simply a band of interlopers.

""We the Original Peoples of this land know the Creator put us here."

|

|

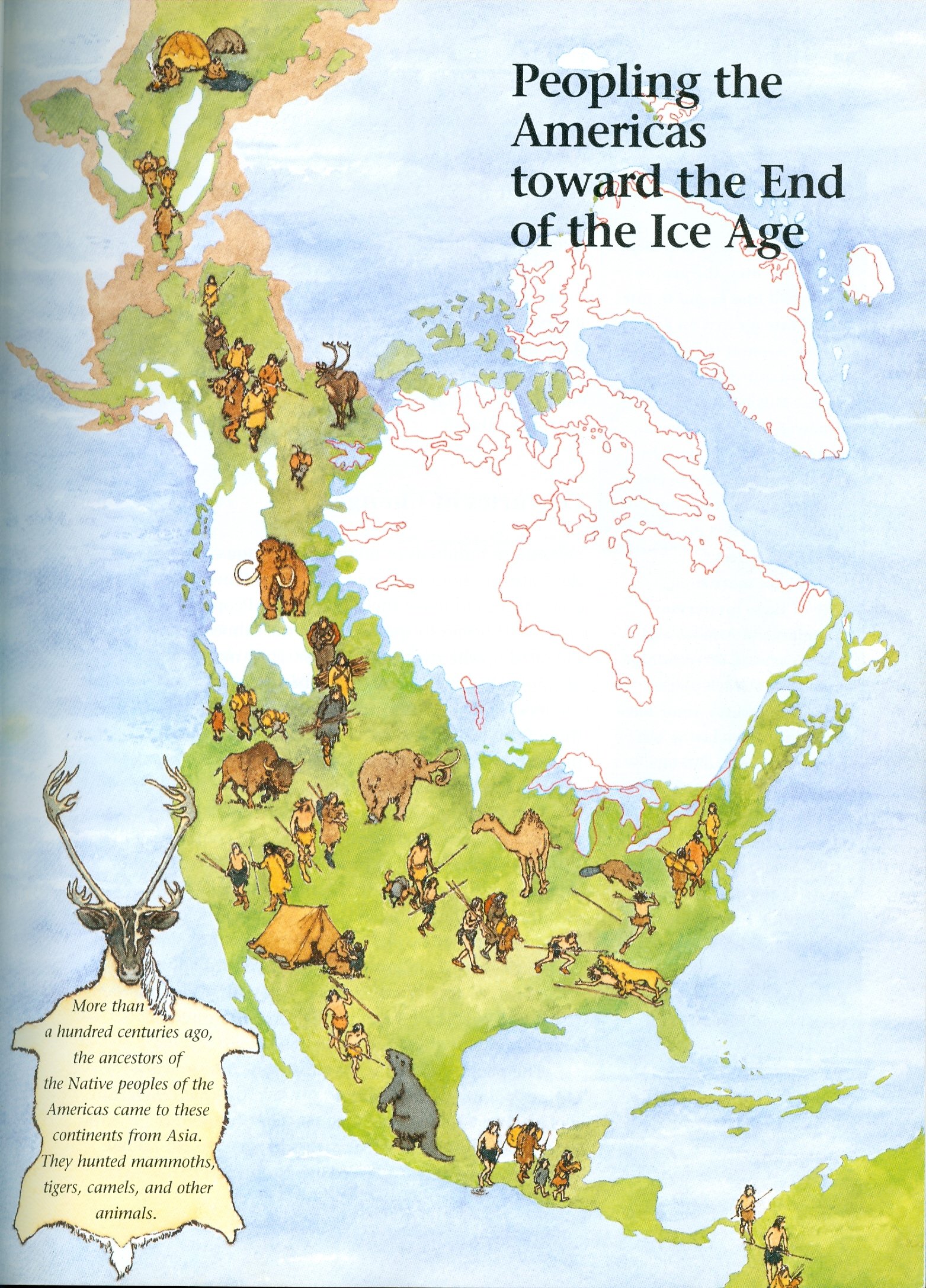

Natives of North and South America |

Aboriginal oral tradition maintains that a Creator placed human beings on earth in North America at the beginning of time. Many Canadian Indian elders accept this as spiritual truth as revealed in sacred myths, dreams, visions. This spiritual belief is vital for it offers a key to understanding the First Nations of Canada, their cultures and their rights to the land. Canada is their homeland, the place where they have always lived. While this claim brings anthropologists into conflict with some Aboriginal peoples, both agree the First Nations had an ancient heritage in Canada. These people of Asiatic origin, who called the continent their own and developed a number of highly evolved Native American societies, were "as different as the Scots are to the Spanish."

|

|

Ojibway; Montagnais; Kwakiutl |

"We have lived upon this land from days beyond history's records, far past any living memory, deep into the time of legend. The story of my people and the story of this place are one single story. No man can think of us without thinking of this place. We are always joined together."

After crossing to Alaska fifteen thousand years would pass before the flow of nomads finally slowed and stopped on the barren rocks of Patagonia. The migrants belonged to either of two distinct families: Indian or Inuit. They resembled each other in the colour of their skin which ranged from brown to yellow but not red. The First Nations owed their allegiance to their family, their band, their village, their tribe and in the case of several tribes, their confederacy. Families grew into clans and clans into tribes and depending on their access to good hunting and fishing. They occupied defined territories which they claimed as their exclusive property. The lands belonged to the tribe collectively and were not divided among its members all of whom had equal rights. Strangers were not welcome. There was no concept of a pan-Indian idenity. Each tribe spoke its own language and regarded its members as "the people." This absence of a recognized common lineage was a significant factor in the Natives' failure to resist the European onslaught. This critical factor was worsened by: their growing reliance on European manufactured products (metal awls, needles and kettles, iron arrowheads and axes); the fur-trade rivalries; the colonial wars; the catastrophic decline in population resulting from exposure to European diseases.

Few 19th century historians would have admitted that Canadian history began prior to the arrival of the first Europeans. Prehistoric times were viewed only as a static prelude to real history. In fact Canadian history began thousands of years before the first arrival of European explorers when native people first crossed the Bering Strait. Europeans who came to Canada saw it as an empty land open for settlement. In actual fact Native people claimed and inhabited almost every part of the "New World" from the tip of South America to the to the Arctic coast, from the Atlantic to the Pacific. "Natives swarmed over the continents and islands from the Arctic to Tierra del Fuego creating communities, establishing networks of trails and trade and adapting the land everywhere to human purposes. At the time of European contact there were more than fifty Amerindian groups in Canada alone."

The European invasion brought on a Dark Age for the native peoples who were cursed by their conquerors as savages and heathens. The unfair advantage of the written word triumphed in the end. A maxim among historians says that the conqueror writes the history. True to this adage European conquerors praised themselves for bringing civilization and salvation to the Americas."

The conquest of the continent of North America is an epic written in the blood and sweat of men and women seeking a place to settle and like all epics it originated with the oral tradition - with tales told around the campfire. Millenia before the arrival of Europeans, Native people were coping in their harsh environments. During antiquity massive mastodon and hairy mammoths trumpeted from the hillsides. The colossal creatures, which roamed over much of North America, were possibly hunted to extinction by the first Stone Age Ice Age people. After the retreat of the glaciers more than 10,000 years ago Native hunters and their families following herds of caribou and other game moved into eastern Canada.

About 5,000 years ago the climate stabilized, slowly moderated and became somewhat similar to what we know today. The Bering Strait attained is present width of approximately eight kilometres and land animals no longer crossed between Siberia and Alaska. The temperature change created an environment in which populations grew and dispersed across Quebec. Nomadic Natives roamed in bands constantly searching for food that included birds, moose, deer, caribou and fish. This diet was supplemented with wild berries and nuts and in some settlements wild rice and corn were cultivated. The corn, in fact, was maize, the latter multi-coloured and eaten mainly after drying and grinding. It was strikingly different from the sweet, yellow, uniform kernels which we call corn. Forests were partially cleared for planting by stripping the trees of a ring of bark (girdling) and burning the underbrush. These open areas and cultivated crops also attracted game. During the winter fish, fowl and vegetation were scarce and these seasonal fluctuations in the food supply slowed population growth.

Despite the absence of the wheel and metal tools, Canada's first immigrants made remarkable advances and achievements. An Iroquois prayer sought the secrets of their world. "Make me wise so that I may know the things you have taught my people, the lessons you have hidden in every leaf and rock." They set about developing sophisticated societies that conformed to local conditions. The list is almost endless of the skills with which Natives accommodated themselves to nature and lived successfully in a demanding environment that was unforgiving of any failure to face and understand it. Early chroniclers were fascinated with the gadgetry and the woodcraft that were developed in the process. Stone Age people shaped stone into knives, axes, gimlets, scissors, hammers and scrapers to which they tied wooden handles with skin lanyards. They fashioned bones, horns and antlers into needles, awls, combs, and heads for spears, arrows and harpoons. Using hardened wood they made hoes and primitive mattocks and wove branches of young trees and plants into hampers and all-purpose baskets. From soapstone they made bowls and lamps, utensils and ornaments. Tribes that knew nothing about pottery-making cooked their food by inserting it in birch bark or skin receptacles which they placed into water heated with hot stones.

In the sprawling half-continent that became Canada, the First Nations lived always by the bounty or the bane of nature. Armed only with bow and arrow they followed prey for great distances frequently carrying tents and all their treasures into richer game country. There never were better, more skilful hunters.

|

|

Across the wide, infinite varied upper continent that became Canada, Indians staked out their hunting grounds. Alfred Miller (15) |

While many Natives were nomadic, the Hurons and Iroquois were able to establish more permanent villages thanks to a knowledge of how to grow maize. Kernels were ground into a flour to which were oil, fish, meat and wild berries were added to make a kind of bannock called sagamite which sustained them on long trips. They also cultivated beans, pumpkins, watermelons and sunflowers. The best land available was reserved for tobacco which was much in demand for smoking during leisure hours and for use at great public ceremonies.

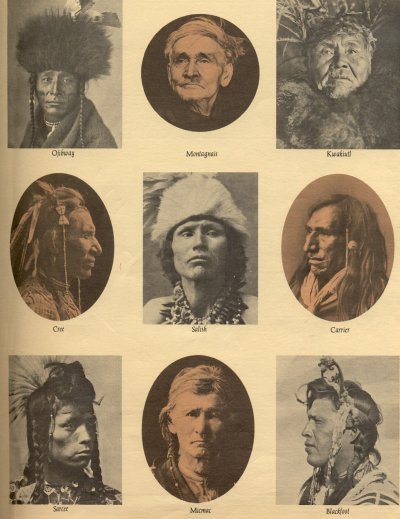

Migratory tribes of the Eastern Woodlands included the Micmac living throughout Nova Scotia, Cape Breton, parts of New Brusnwick, Prince Edward Island and the Gaspe Peninsula. They were among the earliest northern Amerindians to encounter Europeans. They survived in their ancestral homes by serving as middlemen in trade and later as guerilla fighters during colonial rivalries. The sea provided easily accessible food and they became skilled seamen and quickly adapted to the European shallops. Chiefs were chosen on the basis of personal qualities such as being a great shaman or orator whose authority never included the power of coercion.

|

|

An Acadian Amerindian or Micmac |

The Malecite of New Brunswick and the neighbouring parts of Quebec south of the St. Lawarence River shared similarities with the Micmac, but spoke a different language. Their economy was based on inland resouces like fresh water fish and caribou. They and the Micmacs, who were allies of the French, had common enemies - the Mohawk and later the English. The Montagnais lived in eastern Quebec and their close kinsmen, the Naskapi, in the eastern half of the Labrador peninsula. The Algonkins lived between the Ottawa and the St.Maurice Rivers; the Ojibwa in northern Ontario; the Cree from about the middle of the Labrador peninsula westward to the prairies; the Beothuk in Newfoundland. The Micmac were allies of the Maecites and enemies of the Beothuk.

"This tribe (Beothuks)presents an anomaly in the history of man. In Newfoundland there has been a primitive nation once claiming rank as a portion of the human race who have lived flourished and become extinct in their own orbit. They have been dislodged and disappeared from the face of the earth in their native independence in 1829."[*]

The name Beothuk, which probably meant 'man' or 'human being', was considered by early European visitors to Newfoundland to be the tribal name of the Aboriginals then inhabiting the island. First descriptions of these people represented them as "inhuman and wild" It is not known whether the Beothuks retained a faint-folk memory of the era 500 years before, when their ancestors drove Viking invaders back across the sea. , but it was not long before hostilities broke out between them and the new white alien.

Jacques Cartier, a first-rate French navigator sailing under the royal patronage of Francis I of France touched at Newfoundland in 1534 and left this description of the Natives living there. "They wear their hair tied on the top of their heads like a handful of twisted hay with a nail or something of the sort passed throught the middle, and into it they weave a few birds' feathers. They clothe themselves with the furs of animals, both men as well as women." Another observer recorded that "the people are big and tend towards being dark. They call themselves Tabios and live off fish, meat and the fruit of trees."

|

|

Beothuk Wooden Doll |

|

|

Beothuk Canoe designed for rough coastal waters |

Beothuks were called the original "Red Indians." The entire tribe is thought to have numbered no more than 500 individuals at the time John Cabot, who was directed by England's Henry VII to "conquer, occupy and possess for England all lands he might find in whatever ever part of the world they be ." reached the island and "found" these Indians covered in red ochre, partly apparently for religious reasons and partly as a protection against insects. Cabot reported seeing "red men" and this misnomer has subsequently been applied to all Native peoples of North America.

Subsequently European fishermen who settled on the Newfoundland shores in the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, said the Beothuks "carried on a perpetual war with our sailors who are engaged in fishing." Because they "purposely steal Salles, Lines, Hatchets, Hookes, Knives and such like." a bounty was placed on their heads. They were hunted first because they were considered a nuisance and later for the sport of pursuing and killing an elusive game. The English hunted them at every opportunity as did the Micmacs who crossed over from Nova Scotia and pursued them relentlessly, driving them far into the interior of the island.

|

|

Reproduction of a picture that is supposed to have been painted for Governor Holloway in 1808 and shown to the Beothuks in the hope it would be a means of bringing about friendly relations with them. |

Never armed with any weapon more potent than the bow and arrow, the Beothuks tried to defend themselves but were no match for the menace of the Micmacs and the firepower of the whites. Europeans believed the Beothuk had no right to defend their lands from outside intrusion. The white trappers and fishermen who penetrated the island's forests in the 17th century must bear the major blame for their melancholy fate, although the Micmacs, immigrants from Nova Scotia, had a hand in the massacre.

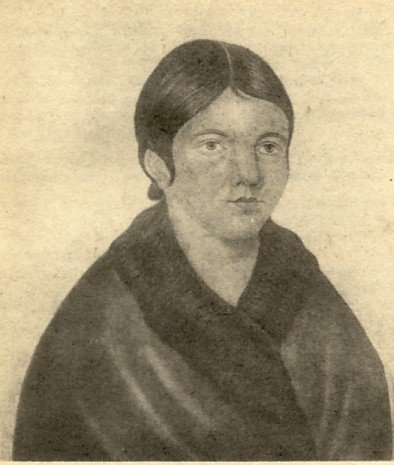

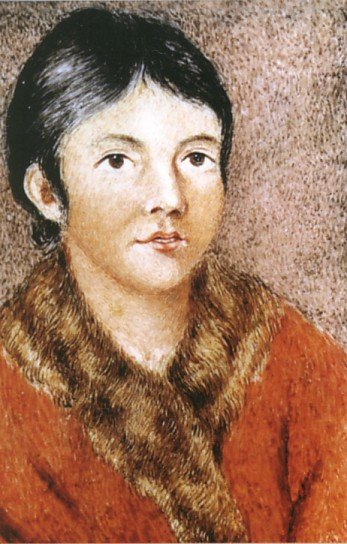

The Beothuk tribe of Newfoundland disappeared from the face of the earth when the two last known survivors of the Beothuk tribe died from consumption which is now known as tuberculosis. One was Demasduit, called Mary March. The other, Nancy Shanawdithit, the neice of Mary March's husband, a chief of the tribe. Nance was the last Beothuk and she died at the home of Attorney General "where every attention has been paid to her wants and comfort under the able and kindly advice of Dr. Carson." She died at St. Johns on the 6th of June 1829. The story of the annhilation of the Beothuk nation is one of the most tragic and brutal chapters in the history of Canada.

|

|

Shanawdithit |

|

|

Demasduit |

Agricultural Tribes of the Eastern Woodlands included the Iroquoians, a linquistic group that comprised the Iroquois - the the Confederacy of the historic Five (later Six) Nations, the Hurons, the Tobacco and the Neutral nations of the Niagara peninsula whom the Iroquois destroyed or displaced. The name Iroquois, whether used as a noun or adjective, refers to member nations of the Confederacy. Iroquoian,the broader term, covers the whole linquistic and ethnic family, regardless of political ties or geographical location. It is comparable to the word 'Germanic,' which refers to Scandinavians and English as well as Germans.

"Man's urge has always been westward, face into the winds that ring the world." The motto that made the early history of North America might well have been 'westword ho we go'.

"The strange boat carrying the tall leafless tree from which a gigantic white blanket was hung must have amazed the Native hunters along the Labrador and Newfoundland coast. They believed the world ended somewhere beyond the horizon and never before in their long history had they seen such a sight emerging from the edge of the world. Upon the sea monster's back rode beings with hair on their faces and with skins like the underbellies of a fish."

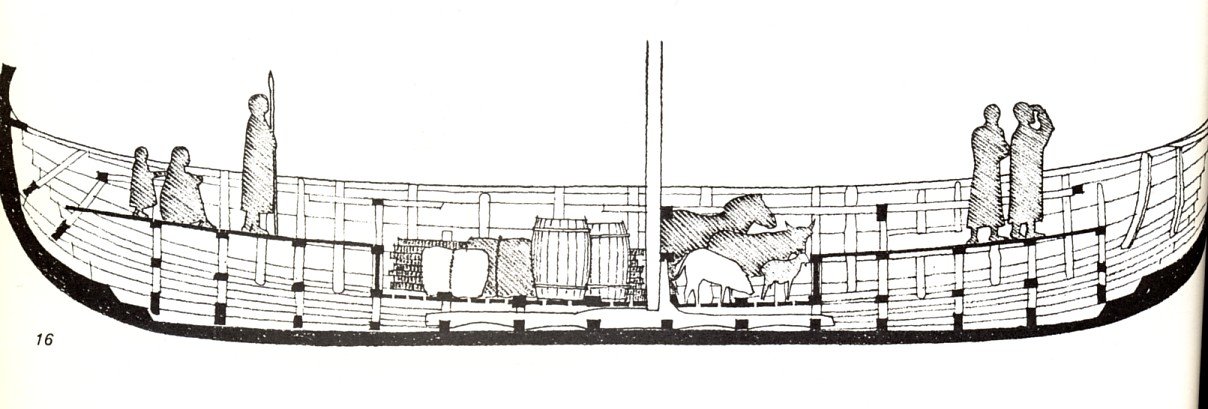

The hairy aliens were Norsemen, the first whitemen to visit North America. One of the Vikings was named Leiv Eriksson, the son of Eric the Red. "A large man and strong of noble aspect," Thorvald, Leif's brother, along with Leif and thirty-five other Norse explorers in their 'dragon' ships with high curved bows and sterns driven by either oars or sails, reached the coast of North America and landed at the tip of Newfoundland's Northern Peninsula about 1000 A.D. These Viking visitors, sons of the fjord, wrote sagas about their experiences in this strange world. One saga related the following incident. "They went ashore and looked about them. The weather was fine. There was dew on the grass and the first thing they did was to get some of it on their hands and put it to their lips and to them it seemed the sweetest thing they had ever tasted."

|

|

Viking Visitors; Leiv Eriksson by Christian Krogh, 1893 |

|

|

Sectional Drawing of Viking Ship |

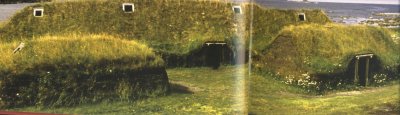

These chronicles became more popular in Canada when at a place called L'anse aux Meadows, the remains of what appears to have been a Viking settlement were discovered in 1960.

|

|

L'Anse aux Meadows |

When a Norwegian archeologist, Helge Ingstad, discovered the site, he found the remains of eight sod houses and evidence of ironworking, carpentry and needlework. Subsequent excavations disclosed hundreds of other artifacts. Ingstad believed that the wine mentioned in the sagas may have been made "from wild gooseberries and the squash-berries that grow in clusters on bushes and from currants or other kinds of wild berries." All these berries are found in northern Newfoundland and for these and other reasons, Ingstad identified Vinland as the island of Newfoundland.

It was left to Leiv's brother, Thorvald, to make the next voyage to the new-found territory, for strange as it may seem, Leiv Eiriksson never returned there. Subsequent attempts at settlement of Vinland were unsuccessful, due to strong friction between the Viking settlers and the native North Americans. The first Native war-whoop in recorded history was heard by Thorvald. Mortally wounded by a Skraeling arrow, he declared, "We have found a fine and fruitful country but will hardly be allowed to enjoy it." Viking arms and armour were little better than those of the Natives whose canoes were "so many that the bay appeared sown with coals." The Norse left Newfoundland after a couple of decades deciding because the Skraelings (Viking name for barbarians) caused them nothing but "constant fear and strife," it was not conducive to settlement.

A manuscript map dating from about 1440 shows Iceland, Greenland and a substantial land mass west of Greenland with the inscription in Latin, "Vineland Island discovered by Bjarni and Leif in company." This is the earliest known map to show any part of Canada and the North American mainland. Aside from this brief Viking interlude Canada as well as the rest of North America awaited accidental discovery anew by subsequent European explorers simply because both blocked the way to the East

PARADISE LOST

In Europe the fifteenth century was a brilliant period, the dawn of glorious enterprise and experiment; the birthdate of great thoughts. Throughout the civilized countries of Europe intellectual life awakened and individual enterprise quickened. It was an age of dreams and romance. It seems fitting therefore that the close of the century should have witnessed a remarkable achievement in the field of exploration - the triumph of Christopher Columbus which placed within the grasp of the Old World the untold treasures of the New.

Seaborne enterprise set free by the compass burst the confines of Europe and found the New World. In fifteenth century Europe visionaries viewed the far horizon and decided to seek a western route to the Spice Islands, Cathay and the empire of the Grand Khan. The fabled name 'India' suggested to Europeans untold wealth and riches and Christopher Columbus, a Genoese navigator funded by King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain, set out to find the fabled place. Some seventy days later the welcome cry of 'land' was heard and the veil of mystery overhanging the western ocean was partly lifted. Thinking he had found India when he landed on the island of San Salvador on October 12, 1492, Columbus designated the Natives he encountered 'Indians,' the name subsequently erroneously applied to all Aboriginals living in North, Central and South America.

Contrary to their belief, Columbus and his successors were not coming into an empty wilderness but into a world which in some places was as densely populated as Europe itself. The cultures were complex, human relations were more egalitarian than in Europe and relations among men, women, children and nature were more beautifully worked out than perhaps in any place in the world.

History has been described as a document-bound discipline and this suggests arbitrarily that Canada's history began with the arrival of the Europeans. Aboriginals were people without a written language, but their laws, their poetry and their history were maintained in memory and passed on in an oral vocabulary more complex than Europe's accompanied by song, dance and ceremonial drama. They paid close attention to personality, intensity of will, independence and their partnership with one another and with nature. In fact, far from being passive partners in European enterprises as they are oftimes portrayed, they were active participants whose involvement was essential for European survival and success in the New World.

What is the proper nomenclature to use in reference to native peoples? "Is it 'Aboriginal Canadians' or 'First peoples' or 'Natives' or 'Indians' or 'First Nations People' or 'Indigenous people'? They're all correct. While we still use the 'Department of Indian and Northern Affairs,' the name Indian has fallen into disrepute. Aboriginals also find demeaning the use of possessives such as 'Canada's aboriginals' and 'Canada's natives,' though 'Native' is acceptable if used to modify 'people' and 'leaders' and 'communities.'" [See Below *]

. Historians agree that prehistoric times ended with the arrival of the Europeans in North America in the 15th and 16th centuries. This is deemed the "period of contact" between the two civilizations. Canada was a 'desert' as both the French and the English then called a wilderness, but it was not uninhabited. Beothuk, Montagnais, Huron and Algonquins, all forest people occupied the wooodlands east of the Great Lakes. Their lives on the whole were good with excellent hunting and fishing. For those who wished action they found frequent opportunities for fighting with neighbouring tribes. Periodically hard times resulted from ecological changes and on those occasions hunters were frequently forced to migrate in search of food.

Prior to the arrival of Columbus it was thought by some that both the Aboriginal people and the land on which they lived had no real history. It was as though the indigenous people of the Americas had drifted immutably across the millennia until they were discovered by the whiteman. On the contrary prehistoric peoples had hightly developed cultures which centred on oral rather than written traditions. There existed in the land that became Canada some fifty different tribes, each with its own particular manners and customs, its own defined hunting grounds and its own separate language or dialect. Seventeenth century northeastern North America, a huge area extending from Acadia westward to the Great Lakes, contained a mosaic of shifting tribes and bands differing greatly in their way of life. When encountered by Europeans in the 16th century the North American population was divided into complex band, tribal, cultural and linguistic subgroups. The northeastern quarter of the continent contained three separate language stocks: Algonquian; Iroquoian and Inuit.

There are many kinds of voices in the world and none of them is without significance. Therefore, if I know not the meaning of the voice, I shall be unto him that speaketh a barbarian. And he that speaketh shall be a barbarian to me."[**]

When Europeans first came to Canada they encountered a race of people who had successfully adjusted to the sometimes harsh environment in which they lived. In these seasonally severe surroundings a man's worth was not judged by European standards of birth, rank, wealth and possessions, but by his strength, stamina, agility and skill as a hunter. The incessant search for food in a rugged wilderness resulted in well-developed individuals who had remarkably keen senses of sight, hearing and smell. Because the quest for food occupied a great deal of their time, First Nations people focussed on practical pursuits and became highly skilled in fishing, hunting and trapping. Little social differences existed among members of the same tribe and all shared the burdens and rewards of the hunt in good times and bad.

|

|

Christopher Columbus |

"We speak of Columbus being the discoverer of America although millions of human beings had occupied this new-found land - this continent - for untold ages."

|

|

Christopher Columbus & Sons Diego and Ferdinand |

During the few centuries that preceded the arrival of the Europeans, Iroquoians lived along the St. Lawrence river from its mouth to Lake Ontario. They spoke a language similar to that of the Hurons living on the shores of Georgian Bay and Lake Huron and similar also to that of the Iroquois living in Northern New York state.

|

|

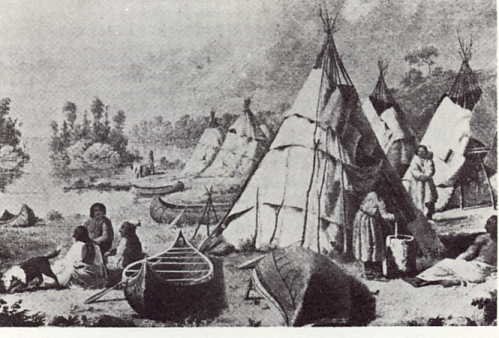

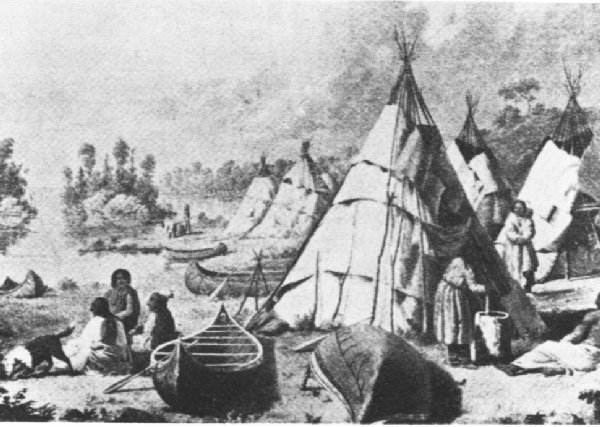

Native Camp on Lake Huron |

They shared with the latter several cultural traits and the same origin. In the 16th century when the Europeans became interested in the Americas, the Iroquoians were present in Old Montreal and in the village of Hochelaga on the island of Montreal. The large Iroquoian villages along the St. Lawrence were divided into provinces. Stadacona and the other villages in the Quebec City region belonged to the province of Canada. The villages in the Montreal region belonged to the province of Hochelaga. Unlike Stadacona Hochelaa was protected by a palisade.

Collision of Cultures

For whatever the reason white man came to the Aboriginals - whether with religion or rum, the Bible or brandy, good intentions or bad - the Natives as well as their habits and the structure of their tribal life were shattered forever by their interaction with the different, complex civilization of the Europeans. When European and the native cultures clashed, the latter way of life changed greatly as a consequence of which Aboriginals survived only two centuries of contact with the white man. "Tension and tragedy" marked their meeting and the transformations that ultimately occurred resulted in a breakdown of the Native society.

|

|

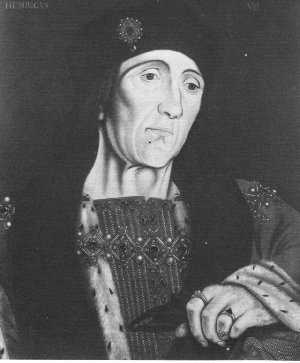

Henry VII |

On 3 February 1498 Henry VII issued new letters patent granting "to our well beloved John Kaboto, Venician," to take six ships of 200 tons or smaller and conduct them "to the londe and Iles of late founde by the seid John in oure name." The Grand Admiral was also authorized to take from the prisons of England all the malefactors he could use on his new venture. Cabot left Bristol in May 1848.

Sebastian Cabot, John's second son, was with his father and it is from Sebastian's recollections that the story of their failed expedition is drawn.

|

|

John Cabot and His Son Sebastian |

|

|

Henry VII |

|

|

John Cabot & the Lord Mayor of Bristol |

|

|

John Cabot's Departure from Bristol |

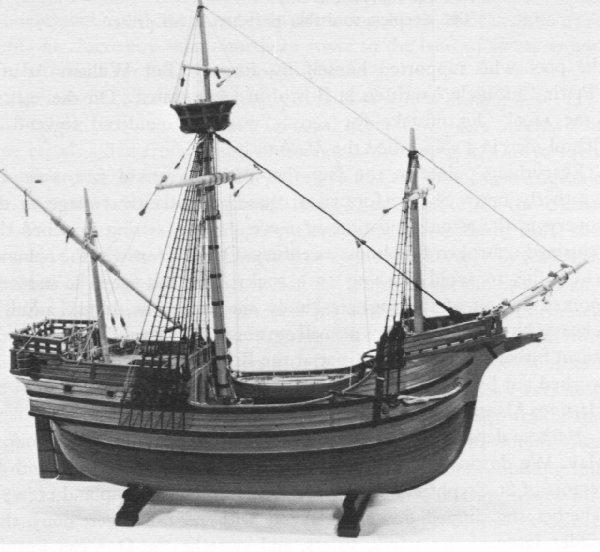

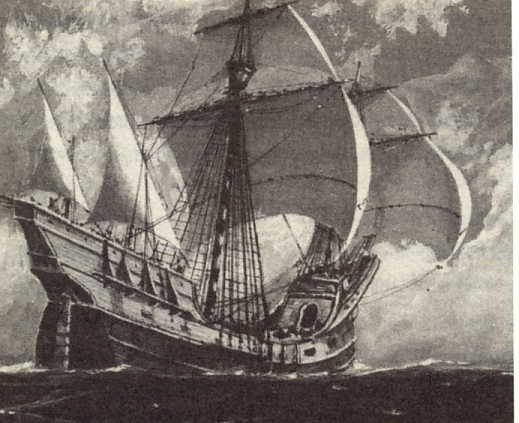

John Cabot was the first white man since the Vikings to set foot on the mainland of either North or South America. Columbus did not land on the mainland of South America until the following years. The brilliant Venetian mapmaker and explorer, who took the English name John Cabot, was authorized by King Henry VII of England to find the northern passage to Asia. In May 1497 he embarked with a crew of twenty men in a single three-masted caravel built of oak with a displacement of fifty tonnes and a length of a mere twenty metres. The vessel was named Mathew, possilby after Cabot's wife, Mathye.

At the quay in Bristol the tiny ship loaded with enough salted fish, meat, hardtack bread and ale to last several months, received its sendoff from the lord mayor and the best wishes of the citizenry. With high hopes and stout hearts, Cabot and his crew anxiously eyed the swelling waves that were sure to challenge the sailing skills of the tough-minded, masterful navigator. Cabot sailed with his sight fixed on the North star. When it was overcast, he used his indispensible compass for there were more grey skies than blue on the North Atlantic.

|

|

Model of John Cabot's Mathew |

|

|

John Cabot Sighting North America |

On the 24th day of June 1497, they saw an end to the ocean for a coastal site lay ahead. Cabot believed it to be the northeastern extremity of Asia. The exact location of their landing is unknown for the ship's log has been lost, but it is thought to have been Cape Breton Island. The anchor was dropped and the little band, their hearts filled with bounding hopes, rowed gratefully ashore. The new land was warm, green and fertile. Codfish could be had simply by letting down and drawing up weighted baskets. With these waters abounding in fish, England would never again have need to buy any from Iceland.

At 5:00 a.m. on the 14th of June, 1497, Cabot claimed for the sovereign "dominion, title, and jurisdiction over those towns, castles, islands and mainland so discovered." He did so by raising on the site where they landed a high wooden cross with the flag of England and the banner of St. Mark of Venice, the city that had granted him citizenship some years before. Cabot believed his feet were planted firmly on the soil of Cathay, the fabulous land of spices, silks and gold. They were the first Europeans since the Vikings to set foot on the mainland of British North America. They saw no sign of life, but the existence of snares for game and notches in the trees proved that people were present in this new found land.

|

|

John Cabot's Landfall in North America |

Cabot's voyages were of considerable importance. He established England's claim to the north-eastern coast of North America and opened up the fishing areas off Newfoundland for England when the country needed a source of supply of such food. All were given a tumultuous welcome on their return to England. Cabot "is called the Great Admiral and vast honour is paid to him and he goes dressed in silk." He was the hero of the hour and "the sunlight of royal favour broke over him in a flood." The king's teeth were said to be "few, poor and blackish," but Henry must have beamed a broad smile when he heard Cabot's account of the voyage. "His majesty has acquired a portion of Asia without a stroke of his sword."

Henry VII knew a good thing when he saw it and responded generously. The royal household books record that on 10-11 August 1497, the king gave the rather modest reward of 10 pounds "to hym that founde the new Isle." On 13 December 1497 the king settled on his "welbiloved John Cabot of the parties of Venice" an annuity of 20 pounds. Cabot spent the 10 pounds "to amuse himself" and swaggered about Lombard Street in gay silken apparel. The common people "run after him like madmen."

John Cabot, whose name as the discoverer of North America, is eclipsed in the mists of the past. Within a year of his discovery, Cabot vanished into history. His fate is obscure for there is no record of his disappearance and when and where he died is unknown. It was said he had gone to "the undiscover'd country from whose bourn no traveler returns." An English historian suggested that Cabot "found his new lands only in the ocean's bottom to which he and his ship are thought to have sunk, since after that voyage he was never heard of more." Sebastian claimed for himself the honours due his father and as a result Cabot's voyage is shrouded in illusion and legend. Sebastian lived to a ripe old age and his presumption and pretension regarding the part he played in the explorations of his father made him the focus of bitter controversies centuries after his death.

Small things often influence the course of history. Perhaps few others decided to risk life and limb to capitalize on Cabot's exploits because of the miserly amount paid by the parsimonious king to the man who discovered a continent. For whatever reason, England failed to follow up on John Cabot's expedition and thus another nation found and settled along the St. Lawrence. Francis I of France decided to support an expedition to les terres neufves.

|

|

Francis I |

Jacques Cartier, a river pilot of St. Malo, was appointed to head it. Cartier, a mariner held in high regard by seafaring men, was forty-three years of age. With two ships and sixty men he sailed from St. Malo, France on April 20, 1534, an overcast, gusty, wind-swept day in the old harbour so rich in seafearing tradition. Cartier was a full-fledged navigator and a captain in quest of riches and a route to Asia. He was well aware that 'America' and 'Americans' had already been discovered. After a relatively fast Atlantic crossing of twenty days, Cartier reached land and followed the shore line northward. He explored along the bleak, rocky, infertile coast of Labrador, land he contemptuously labelled that "God gave to Cain."

|

|

Jacques Cartier |

|

|

Jacques Cartier's Home In St. Malo |

|

|

A French Caravel |

The French dicovered there a "wild and savage folk" who painted themselves "with certain tan colours," their reddish hue heralding for all time the name that stuck - 'red' Indian. Cartier proceeded through the Strait of Belle Isle and south along the western coast of Newfoundland then across the open waters towards Prince Edward Island and along the New Brunswick coast. Cartier returned to France with tales of the timber, fish, furs and fertile lands he had found.

Impressed with Cartier's accounts of the prospects awaiting in the new land, Francis I ordered another expedition. In 1535 Cartier set sail with three ships and before long he was exploring along the coast of Newfoundland and in the bays of the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Finding different tribes of Aboriginals wherever he went, Cartier recorded that these North American Natives were not all alike. They spoke different languages, practised contrasting lifestyles and warred with each other. Cartier crossed the gulf to an island he named St.Jean (Prince Edward Island). Turning toward the northwest he followed the outline of the coast where he saw "the fairest land that may possibly be seen full of goodly meadows and trees." They had reached the shore of what is now New Brunswick. Because the heat was so intense in the bay in which they anchored, Cartier named it Chaleur and the Bay of Chaleur it has been ever since. When the Frenchmen left the ships to go ashore they recorded that many eyes were watching them.

|

|

Cartier and The Aboriginals |

Before long canoes appeared filled with lithe, lean, rugged, fearsome-looking fellows. Cartier and his men quickly turned their boats about and rowed back towards the safety of their ships. The Natives with fiercely painted faces "hideously with red and white ocre" paddled furiously, and with speed that astonished the Frenchmen quickly surrounded them. They signalled their desire to trade but Cartier "did not care to trust their signs" and fearing a fight raised his arm as a signal. One ship discharged two small cannons and their extraordinary noise frightened off the Natives. They did not go far before curiosity overcame their concerns and they turned about and once again approached the bearded strangers. This time Cartier ordered his men to raise their muskets and fire into the air. The sharp volleys that shattered the stillness shook their courage and curiosity and they fled from the terrifying noise. Cartier noted in his diary that they "would no more follow us."

But follow they did and Cartier provided the first detailed description of the ceremonials surrounding trade with these Aboriginals he had previously driven off. They returned on July 7th, "making signs to us that they had come to barter." Cartier had come prepared with well-chosen trade goods that included "knives and other iron goods and a red cap for their chief.". The Natives eagerly offered their beautiful pelts for tawdry trinkets from the first whitemen they had ever seen. Before long they left stripped even of the furs on their backs.

Initially the Aboriginals extended a warm welcome to the white men and helped them to survive the savage winters by sharing their wisdom and wide knowledge of the wilderness. Their inventions were invaluable. The birch bark canoe enabled the European explorer, missionary, trader and colonist to travel quickly into the heart of the continent. Natives became the whiteman's guides, taught them routes to follow and signs to note as they moved through the great primeval forests. They taught them the ways of the forest, how to keep one's bearings in the bush and how to live off the land. Their snowshoes were an indispensable way of getting over deep snow easily in winter and the tobaggan was invaluable for hauling provisions. Natives gave the newcomers precious pemmican (lean, dried meat pounded fine and mixed with melted fat) to sustain them during long-distance travel. They taught them how to gather and boil down maple sap for syrup and sugar. They taught Europeans about the medicinal properties of certain plants and not the least of their legacies how to grow and use tobacco.

As the numbers of newcomers grew and tensions replaced toleration one wonders why the Natives in the early stages never decided to simply overwhelm the whites. This was not as simple as it might have seemed since the first whitemen concentrated around fortified villages supported by a monopoly of sea power and arms. The Aboriginals quickly developed a ferver for muskets which they used to hunt game and rival tribes but these wonderful weapons made them dependent on the whites for ammunition, powder and repairs. Located as they were along coasts, the whites fought ferociously since they had no where to run. Indians on the other hand could always lose themselves in the forest if besieged by the Europeans. The flow of whites seemed inexhaustible. There was always a ready supply of reinforcements while Native tribes were riven by tribal feuds. Fatally for the Native nations were the whiteman's "invisible armies" whose virulent infections spread like wildfire through people with no genetic immunity.

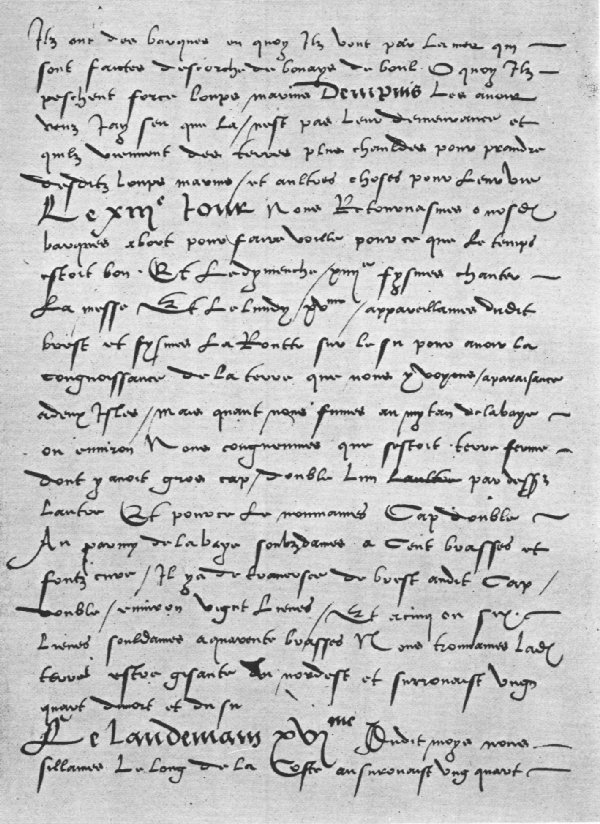

|

|

Page from Cartier's Diary |

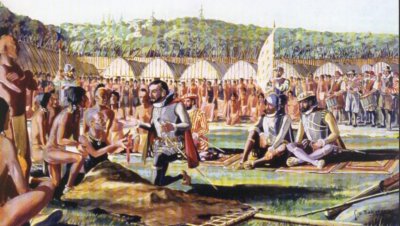

Cartier came to Canada again in 1541 hoping to find the Great Lakes and the elusive route to China. He visited with Chief Donnacona at his village Stadacona (Quebec City) lying at a point where the mighty river St. Lawrance narrows to the breadth of a mile. On the 19th of September Cartier continued travelling west hoping the great river would bring him ever closer to the fabled orient. During the thirteen day journey to Hochelega the French travellers were awed by the brilliant coloured leaves bedecking "the finest trees in the world" which included maple, oak, elm, pine, cedars and birches. Their trip was suddenly interrupted by rapids in the St.Lawrence which Cartier named La Chine (China) Prevented by La Chine from proceeding further up the St. Lawrence, Cartier left the ship well guarded and continued by boat. He finally reached open fields behind which a loomed a great mountain. This elevation, the highest along that section of the St. Lawrence, was called Hochelega (Montreal) by the Natives. While the village was impressive it was not the sought after city of the East.

|

|

Cartier at the large Iroquois settlement of Hochelega, site of Montreal |

Cartier and his men climbed the mountain from whose height they beheld so splendid a panorama that Cartier called it Mount Royal. A great plain "smooth, level, tillable, the fairest possible to see" separated them from the mountains on the south. The silver gleam of the mighty river "grand, broad, extensive, stretching to the west until lost in the distance" lay before them. Like Moses from Mount Nebo they stared westward at the promised land on which they would never tread for they could go no further. The Lachine Rapids surging downward at a speed of eighteen kilometres an hour barred passage.

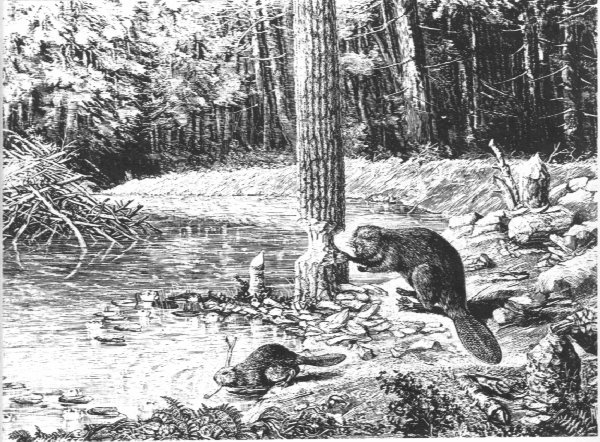

|

|

Castor canadensis (North American Beaver) |

Sixty-eight years later in 1603 the Founder of Canada, Samuel de Champlain, sailed up the St. Lawrence River and discovered not the Iroquois Natives Cartier had encountered but Algonquins occupying the same area. Iroquoians then controlled the peninsula of southern Ontario south and west of Lake Simcoe. Included in this linguistic group were 16,000 Hurons (Wyandots) who were allied in origin and language to the Iroquois. To the southwest were

|

|

Samuel de Champlain |

the allies and kindred of the Hurons, the Tobacco or Petun Nation, their name coming from their custom of cultivating large fields of tobacco, a commodity they used in widespread barter with other tribes. (Tobacco is still an important crop in their ancient lands.)

Cartier was intrigued by the Huron's use of tobacco smoked " in a hollow bit of stone or wood." The early pipe looked more like an enlarged cigarette holder, the bowl simply an enlargement of the stem with its opening in the front instead of on the top. The Iroquoians cultivated tobacco, a primitive variety different from today's tobacco, which they smoked in fired clay pipes.

Cartier provided this description of the Huron's use of tobacco.

"At frequent intervals they crumble up this plant into powder which they place in one of the large openings of the hollow instrument and laying a live coal on top suck at the other end to such an extent that they fill their bodies so full of smoke that it streams out of their mouths and nostrils as from a chimney. They say it keeps them warm and in good health and never go about without these things. We made a trial of this smoke. When it is in one's mouth one would think one had taken powdered pepper it was so hot." This was probably the white man's first experiment with tobacco and it occurred some fifty years before Sir Walter Raleigh began to popularize smoking in Queen Elizabeth's London.

Southeast of the Petuns and west of Lake Ontario on both sides of the Niagara gorge was the Neutral Confederacy, the peaceful Atiwandaronks (People who speak a slightly different tongue). They were named the Neutrals by the French because they took no sides and refused to allow fighting within their territory.Friends alike of the Iroquois, the Algonquins and the Hurons, Champlain described them as a powerful people having "forty populous villages." The Neutrals were "the only nation living in total peace." Confederation of tribes was common and Natives formed a confederacy or shifting alliance of tribes comprising five groups occupying from 28 to 40 villages lying south and east of Huronia. Champlain said they lived "West of the lake of Entouhonoronons (Lake Ontario) and north of Lake Erie and extended across the Niagara River." East of the Neutrals and occupying the basins of the Genese and Mohawk Rivers was the dread confederacy of the Five Nations.

|

|

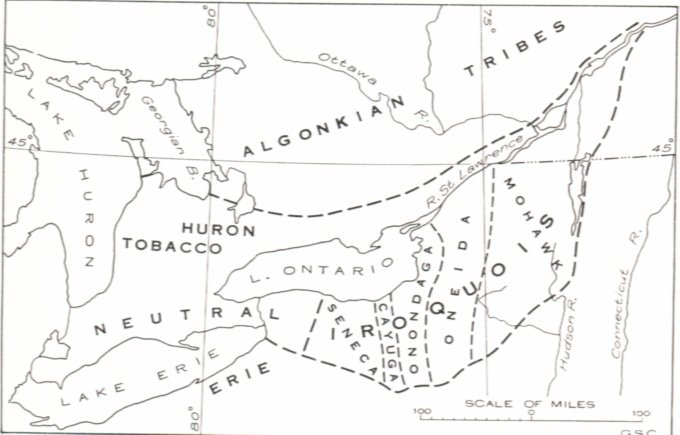

Iroquoian & Algonkin Nations |

Peering through the mists of time it is possible to examine the basic patterns of life which affected Indian thought and action. The confederacy of the Hurons (from the Old French Huron, a bristly, unkempt knave) consisted of four separate tribes: the Bear, the Cord, the Rock and the Deer along with a few smaller communities that united with them at different periods for protection against the League of the Iroquois. The Hurons occupied a rich area of conifer and deciduous forests west of Lake Simcoe and east of Georgian Bay. In 1603 according to Champlain almost all were centred on Georgian Bay and the area of Lake Simcoe. Jacques Cartier was the first European to meet them at the Huron villages at Stadacona (Quebec City) and Hochelaga (Montreal Island). The real name of the confederacy was Wendat (Islanders or Dwellers on a Peninsula) from which came the name Wyandot that was applied to the mixed remnants of both the Hurons and the Tobacco people. The strongest tribe was the Bear numbering about half the total population.

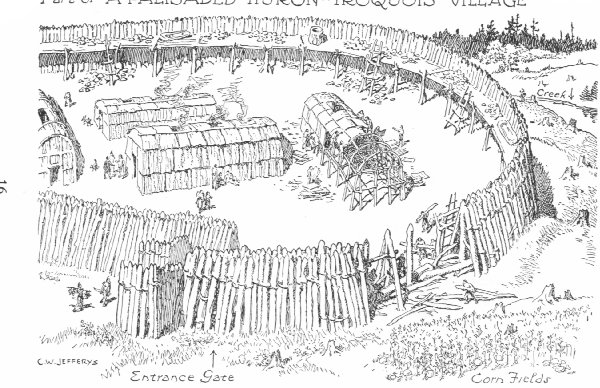

The Iroquoian tribes were sedentary and lived in bark houses located within palisaded villages all joined by networks of trails. Near each fortified village there were fields of corn, beans, pumpkins and tobacco. For some Indians particularly the Iroquois agriculture became very important. They raised fifteen varieties of corn, sixty kinds of beans, eight sorts of squash in addition to other foods and tobacco. The men cleared the fields by slashing and burning and the women did the actual planting in early spring. For corn the earth was hilled to help the roots take hold - a practice early colonists adopted. Several seeds, usually four, were planted in each hill, "one for the beetle; one for the crow; one for the cutworm and one to grow."

|

|

Palisaded Huron-Iroquois Village - Jefferys |

Only eight of the eighteen villages were fortified with palisades and ramparts. When danger threatened residents of the unfortified villages fled for refuge to the nearest fortified village or simply dispersed into the forest. A village usually contained no more than twenty or thirty dwellings each accommodating from eight to twenty-four familes with an average of five or six persons per family.

Dwellings were separated by short distances to avoid complete destruction in event of fires which occurred frequently because of the open fires and the bark huts. Agricultural in habit, keen traders and in the main sedentary, these people made short hunting and fishing excursions and laid up stores for the winter. No settlement lasted longer than twelve to twenty years on account of the depletion of the fuel supply and the exhaustion of the unfertilized soil. Life was normally quiet and peaceful with few dissensions within a village but tensions were more common between the different tribes. Around the villages and their cornfields there were dense woods inhabited by deer, bears and wolves. There were paths radiating throughout the forests to neighbouring villages and where rivers and streams existed they were crossed by wading or swimming.

|

|

Hurons In Aboriginal Dress |

The Hurons maintained a close friendship with the Algonkins to the north and east.Years before they had fought with their neighbours, the Tobacco people, but by the time Champlain penetrated into southwestern Ontario they had cemented close relations. The only enemies of the Hurons were the Iroquois living south of the St. Lawrence River. The Hurons were not unique in this regard for the Iroquois warred with any neigbours who refused to enter their League. The Neutrals lived squarely in the path of the Iroquois and for years they and the Hurons had steadfastly ignored every plea from the League of the Iroquois to fulfil their dream and join them in establishing the "Great Brotherhood."

|

|

18th Century Iroquois Warrior |

Warfare took the form of raids and counter-raids during which no holds were barred. The Iroquois were without doubt the best warriors in the region. At first they struck in small raiding parties and these sporadic ambushes and retaliations seldom produced much change in tribal dominance. They did, however, provide warriors with their chief interest in life - proof of personal courage in combat. One French explorer described them. "They approach like foxes, fight like lions and disappear like birds." Offensive weapons used on both sides included clubs, stone axes and bows and arrows. Tomahawks did not appear prior to contact with Europeans. [***] Some warriors used slat armour and wicker shields covered with rawhide to protect themselves from bone- or stone-pointed arrows but these protective devices were abandoned once muzzle-loading guns appeared on the scene.

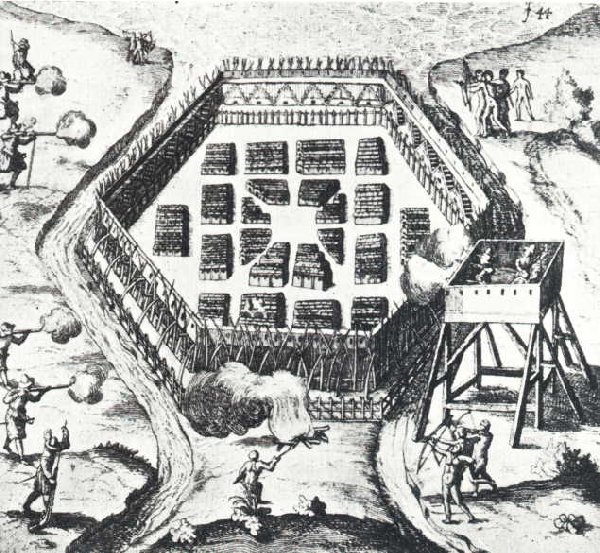

Neither side had really efficient military organizations. There was no discipline to speak of since individual warriors could drop out of a conflict whenever they wished, incurring when they did so no other censure than a little loss of public esteem. Defence like discipline was also loose. Some villages were protected by palisades but most were not. Where no palisades existed Natives under unexpected attack fled into the forest. Close contests between the two Confederacies might have continued indefinitely had the Iroquois not acquired more firearms and ammunition from the Dutch than the Hurons obtained from French fur traders along the lower St. Lawrence River.

The Iroquois system protected individual liberties and freedoms and included gender equality. Thomas Jefferson, America's third president and one of the drafters of the U.S. Constitution, observed that among the Iroquois "every man with them is perfectly free to follow his own inclinations. If in doing this he violates the rights of another, if the case be slight, he is punished by the disesteem of society or as we say, public opinion. If the case is serious he is tomahawked as a serious enemy." Jefferson used this concept to draft his First Amendment which allows freedom until it violates another person's rights. Benjamin Franklin was so impressed by the Iroquois Confederacy that he championed it as a model to unite the new colonies and urged that each colony become a state with control over internal affairs and with a federal council responsible for external matters. This became the basis of the Articles of Confederation. The federal systems of government in Canada and the United States are modeled on the system of government devised by the Iroquois.

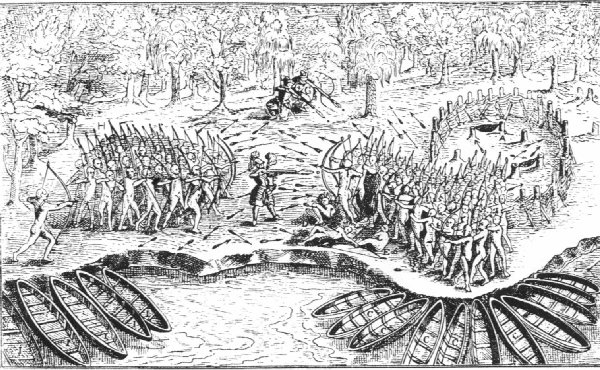

|

|

Hurons and French attacking a palisaded Onondaga village |

The Tobacco people or Tionontati (There the mountain stands) and the Neutrals were hardly distinguishable from the Hurons in their customs. In 1640 the Neutrals had only nine villages while the Tobacco had twenty-eight. Neutrals had little contact with the Europeans because the Hurons, fearful of losing their trade status as middlemen, never allowed passage through their territories to the French settlements in Quebec and the upper St. Lawrence was blocked by the Iroquois. In any case the Neutrals would have found it difficult on the St. Lawrence River route because they were not skilled in the use of canoes.

The League of the Iroquois, known by the neighbouring Algonkins as Real Adders, comprised five small tribes strung out along the hills of what is now western New York state. Known as the Five Nations this later became the Six Nations when the Tuscarora, an Iroquoian tribe, was driven out of North Caroline and accepted into the confederacy about 1722, The map above indicates their approximate locations and boundaries around 1600 A.D. Each of the Five (later Six) had its own language, its own name and its own history but collectively they called themselves Haudenosaunee,(People of the Long House).

In order from east to west they were:

(a) Mohawk (Man Eaters) at the eastern door; they were the "People of the Flint."

(b) Oneida (A Rock set up and standing) They were the "People of the Stone."

(c) Onondaga (On the hill or mountain) They were the "People of the Mountain."

(d) Cayuga (Where locusts were taken out) were the "People at the Landing."

(e) Seneca (A distorted variant of Oneida, the two names having a common origin.) They were "the great hill people."

The largest tribe, the Seneca, numbered about 7,000. They were the "keepers of the west door" The smallest was the Oneida numbering a thousand. Next were the Mohawk numbering about 3000. They were the "people of the east door." Politically, the important members were the Seneca, Mohawk, and Onondagea. The last-named numbered about 3000 and were the "keepers of the council fire." Occupying a position that was central geographically and also in inter-league relations they served as law-makers, arbitrators and achivists, "keepers of the archival wampum." The Cayuga numbering some 2000 specialized in rituals and played a lesser role as did the Oneida. In fact the Cayuga were said to be offshoots of the Onondaga as the Oneida were of the Mohawk. At no time did the Five Nations count more than 2500 warriors and these were never all sent into battle at the same time.

Dissension within the confederacy was reduced by building in a system of clan kinships that went beyond the borders of different tribes. A lineage consisting of a number of closely related "firesides" (nuclear) families living under one roof was the building block of the clan. In larger villages lineages belonging to the same clan lived in adjacent longhouses. Typically, clan members were identified by a symbol. Clans of the Hawk, Turtle, Wild Potatoes, Great Bear or Deer Pigeon would have had members among the Mohawks, Seneca, Onondagas, Oneidas, and Cayuga alike and these individuals viewed each other as members of the same family.

At no period in their history were the Iroquois a numerous people. Around the coming of the Europeans their total population excluding the Tuscarora was only about 16,000.[****] The most aggressive were the Mohawks, the fighting backbone of the Confederacy. Their sheer ferocity on the war-trail made them seeminly invincible in any numbers and of all the woodland tribes they became the most dreaded adversaries. Their very name struck terror into the hearts of those who heard it. The frantic cry "The Iroquois are coming!" demoralized any foe they were about to fight.

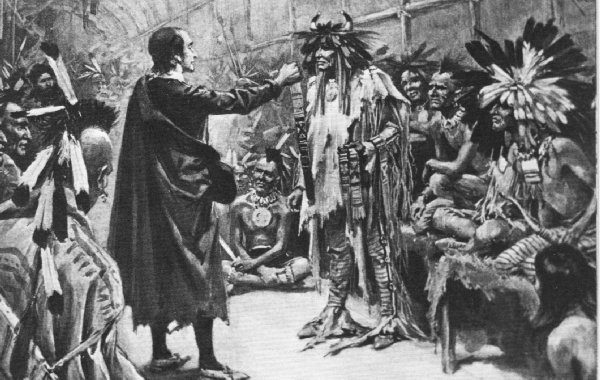

|

|

Mohawk Warriors and French Missionary |

Flanking both ends of the confederacy meant the Mohawks and the Seneca tribes encountered their various enemies first and because of the confederacy's loose organizational structure they often acted independently of all the other tribes. The Senecas were chiefly responsible for the destruction of the Huron, Tobacco and Neutral nations. The Mohawks took on the task of harassing the Algonkins, the Montagnais north of the St.Lawrence, the Abenaki and various other Algonkian tribes in the Maritime Provinces, New Hampshire and Maine. The three middle tribes contributed contingents for all major operations. Their numbers were: Cayuga: 2,000; Onondaga: 3,000; Oneida: 1,000. Because of their independent nature, problems sometimes arose when one tribe of the confederacy concluded a peace treaty with an opponent that was ignored or dismissed by the others. An example of this occurred in the seventeenth century when the French concluded a hard-won truce with the Mohawks only to find themselves suprised and dismayed to be assailed by parties of the Onondaga and Seneca tribes which did not recognize the Mohawk's moratorium on warfare with the whites.

|

|

Huron Indian Camp of Circular Wigwams |

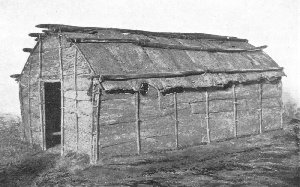

The name Hotinnonsioni(Builders of Cabins) has been given to the Iroquois. These people were the most comfortably lodged in long houses. These contrasted with the small, circular wigwams of the Algonquian tribes usually housing only one family.

|

|

Model of Long House |

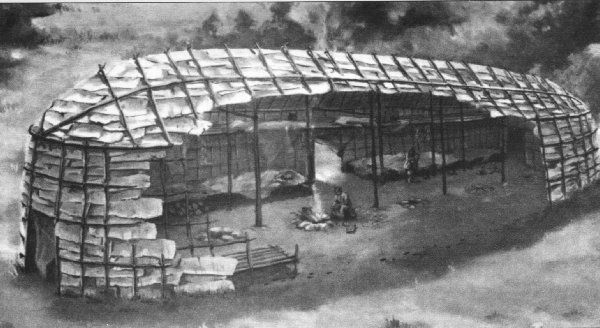

Early whites saw long houses that were "fifty or sixty yards long by twelve wide with a passage ten or twelve feet long down the middle." number of fires they contained. Each fire added twenty or twenty-five feet to the length of a cabin and they did not exceed thirty or forty feet. A typical town might have fifty of such dwellings and one was said to have two hundred. The towns were surrounded by a ditch, rampart and stockade so strong the English used to call them castles. Each rested on four posts for each fire which were the base and support of the entire structure. Around the entire circumference, that is the two sides and the two gable ends, pickets were planted to secure pieces of elm bark wich formed the walls and which were bound together with strips made from the interior coating or inner bark of white wood. The roof framing was made with poles bent to form a bow which were covered with pieces of bark. These pieces overlapped like slate. Inside the middle space was always the place of the fire from which the smoke escaped through an opening made directly above it in the roof which served also to provide light since there were no windows. Movable pieces of bark were used to cover the hole during heavy rains.

|

|

Iroquoian Longhouse Based on Archeological Evidence |

Subsequent to 1603 Champlain travelled back and forth between France and Canada a number of times. During his travels up the St. Lawrence it became clear that conditions had indeed changed since the days of Jacques Cartier. The fierce tribesmen encountered by Cartier were mild-mannered men compared to the Natives south of the St. Lawrence who inspired fear and dread among all who knew of them. While Champlain did not immediately come into contact with this fiercesome force that lived in palisaded villages among the lakes of northern New York, he had numerous reports of their cruel, conquering ways. They were a people who brooked no opposition. They called themselves the Ongue Honwe, "the men surpassing all others."

On the nineteenth of June, 1609 several shallops manned by twelve men each bearing a short-barreled arquebus slung over his shoulder arrived at the broad, deep, beautiful mouth of the "river of the Iroquois" (the Richelieu) which was broad and bland. The Indians assured Champlain they could sail up it to the Lake of the Iroquois. As they did so they were about to enter territory no white man had ever seen before. In the prow of the lead shallop was the intrepid, insatiably curious Samuel de Champlain peering intently at the shoreline, enrapturd by the unspoiled, primitive landscape whose woods came down to the shore. In the wake of the shallops were twenty-four canoes bearing sixty allies of the French, a war-party comprised of Native braves from the Montagnais, Algonkins and Huron confederacies. Champlain had promised to go with them on the warpath in return for which they promised "to take me to explore the Three Rivers as far as a place where there is such a large sea that they have never seen the end of it." Champlain was fulfilling his end of the bargain.

The lower stretches of the Richelieu River were easy going, winding among "many pretty islands which are low, covered with very beautiful woods and meadows." Animals, which were abundant and little disturbed by their presence since no one lived in this no-man's land provided all the food they required. On reaching the roaring rapids at Chambly, Champlain found they were handicapped by the heavy shallops which could not be dragged through the rapids and were too big to portage among the large trees on shore. Champlain called for volunteers to accompany him further. Only two stepped forward. All the others quailed at the prospect of what was to come. "Their noses bled," said Champlain. After ordering the remaining Frenchmen to return to their settlement at Quebec, Champlain and his two companions set off with the Indians in their light, bark canoes which could float in a few inches of water and be carried by one man easily over the winding wilderness trails. The Frenchmen carried all their baggage as well as their heavy arquebuses, powder, match and shot. They wore steel armour.

|

|

Building A Bark Canoe |

Champlain recorded the following in his journal.

"I set out then from the rapid of the river of the Iroquois on the second of July. The Indians took their shields, bows, arrows, clubs, swords fixed to the ends of long sticks and their canoes and carried them about half a league by land to avoid the swiftness and force of the rapid. They made their way so fast that we soon lost sight of them. This displeased us but we followed their tracks but often went astray and would not have known where we were had we not caught sight of two Indians moving through the bush. We called out to them and they agreed to guide us. The others were travelling quickly on ahead." After rowing 120 kilometres they entered the largest body of inland water they had ever seen, a lake which Champlain named after himself.

"On the evening of July 29th we sighted off the point while later was to be the site of Fort Ticonderoga, a number of canoes that the our Indians immediately noted were heavy in the water, a fact indicting they were made of elm bark - the tree of choice of the Iroquois. Hardly had we gone an eighth of a league further before we heard the howls and shouts of both parties flinging insults at one another and with scattered skirmishing whilst waiting for our arrival. As soon as our Indians saw us, they began to shout so loudly that one could hardly have heard thunder."

|

|

Champlain at Lake Champlain |

Contrary to the established practice of Indian warfare the two parties approached each other openly and challenges to battle were hurled in jeering voices across the tranquil water. Two Iroquois canoes paddled out for a parley to learn from their enemies whether they wished to fight and they replied they had no other desire. The Iroquois were too well trained in forest fighting to risk conflict on the water and since it was dark and they could not distinguish one another they said as soon as the sun rose they would attack us. This was the etiquette of war; a parley and an agreement on the hour of battle. Once this was completed the Iroquois returned to the shore from where they hurled taunts of their enemies' feebleness and foretold how they would be exterminated by the prowess of the Iroquois warriors. Champlain's allies yelled back that the Iroquois were going to experience a power of arms such as they had never seen before.

The Iroquois then disappeared into the forest where throughout the night they danced to the flickering light of their fires, singing all the while war songs in high, shrill voices, songs of insult and songs of celebration of their coming triumph. They had no doubts whatsoever that victory would be theirs. Champlain's companions returning jeer for jeer spent the night in their lashed-together canoes. Champlain wondered at their resolve in the face of such fearsome odds for the Iroquois appeared to outnumber them four to one. Was their seeming bravado simply a case of whistling in the dark? It was hard to remain confident in the face of the awesome uproar coming from the Iroquois camp.

Morning found the Frenchmen donning their breastplates, the highly polished metal reflecting the rays of the rising sun. Then with the Frenchmen lying hidden on the bottom of the canoes the Indians paddled to shore unhindered by the Iroquois where they formed in battle array. With carbines loaded and sword and dagger dangling from their waists, Champlain and his companions advanced warily, their fingers steady as they awaited the onslaught. Finally the Iroquois warriors appeared marching solemnly into battle with taunting laughter, "strong and robust to look at coming slowly toward us with a dignity and assurance that pleased me very much.They numbered about 200 strong, robust men led by three plumed chiefs. The allies said I should do all I could to kill them."

Champlain was most impressed with his foes' physical magnificence. Tall, lithe, splendidly muscled, they were a superior looking enemy. Three chiefs, their heads topped with snowy plumes, strode ahead, their hysterical howling and fierce demeanour frightening to behold. The Indian allies parted and Champlain moved forward slowly through the opening. Seeing a whiteman for the very first time, the Ongue Honwe fell silent, their fierce eyes filled with wonder and awe. Surely this was a white god. With no sign of haste, his arm and aim steady, Champlain pointed the arquebus loaded with four bullets directly at the three chiefs and pulled the trigger. His eye and aim were excellent for the explosive charge felled all three of the chiefs, killing two instantly and the third after a short period.

The sudden explosion followed immediately by three fallen chieftians jarred the senses of the Iroquois. However, it also released them from their transfixed spell. In the face of the thunder and lightning of this awful god they realized they had to fight or die and they loosed a barrage of arrows at their enemies. At this critical moment the other two Frenchmen stepped forward from the side and fired point-blank into the aroused Iroquois. More gods and more roaring thunder were just too much. The Iroquois were proud warriors but the sight of all that flash and smoke coupled with the sound of the explosions caused the terrified warriors to turn and make for the woods, fleeing for the first time ever in the face of their hated enemies. Their harried howling and panicked flight brought the Native allies to life and with hatchets and scalping knives brandished they sprang forward in pursuit of their fleeing foe.

|

|

Champlain's Musket Blast |

Champlain's first musket blast ensured French-Iroquois conflict for years to come. Espousing the cause of the Montagnais, Algonquins and Hurons against the Iroquois was to have bloody repercussions. Champlain's participation in 1609 with his allies in their successful assault against a Mohawk war party on Lake Champlain resulted in a bitter feud between the French and the Iroquois confederacy. The people of the Long House never forgot nor forgave and nursed a hatred for the French that the years did not diminish nor the spilling of blood ever sate. Even after the Hurons had been exterminated and the Montagnais ceased to count the feud festered. The Iroquois's smouldering wrath vented itself in furious raids on the settlements of New France.

The fate of the English, Indians and French was intertwined. In the French-English conquest to come to control the vast Iroquois empire that beckoned the European powers, an alliance with the Iroquois was to prove vital. The Aboriginal influence was to be immensely important to the conflict. While the Iroquois had no great regard for the English, when the two nations were at daggers drawn as was so often the case the Six Nations always allied themselves with the British. The French feud with the Iroquois blocked France's extension southward and made the Iroquois-English alliance extend right down to the capture of Quebec by General James Wolfe in 1759.

Little did the Iroquois chiefs and their warriors realize that the prize both Britain and France were seeking was the very land on which the Natives lived.Fur trade became the life blood of the French colony and the most important animal fur by far in Canadian history was that of the beaver. It inspired the fur trade that led to the exploration of the Great Lakes and contributed to the war between France and the Iroquois and Britain. Colonization was possible only if the fur trade flouished enough to retain the financial backing of business associates in France. This required the efforts of the Montagnais and the Algonkins whose long flotillas full of furs floated down the Ottawa to trade at Hochelaga. In order to maintain this source of fine furs Champlain had to support his natural allies in their never-ending conflict with the Iroquois. If he wanted their furs he had to fight beside them. At the time no other course seems to have been open to Champlain whose actions were the result of a carefully considered policy.

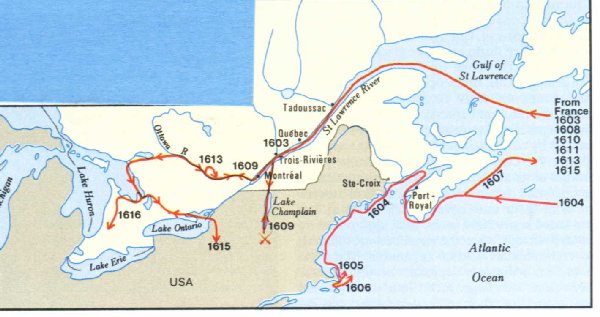

|

|

Champlain's Travels |

In July 1615 Champlain ascended the Ottawa River, crossed Lake Nipissing and descended the French River to Georgian Bay where he visited the Huron Villages. In August he set out with a war party of Hurons to attack the Iroquois. Their route was by way of Lake Simcoe, the Trent River, the Bay of Quinte and across the foot of Lake Ontario from where they entered Iroquois country. French firearms had little impact on the course of the fighting. The expedition proved to be a failure. The Hurons withdrew after a number of them were killed and Champlain wounded.. This defeat destroyed the psychological edge the French and their allies had earlier gained over the Iroquois. When the Iroquois began to acquire arms from the Dutch who were settling in Pennsylvania, this turned the tide in favour of the Mohawks. They gradually extended their sway over all the territory from Tennessee to the Ottawa River and from the Kennebec River in Maine to the southern shore of Lake Michigan.

The Europeans brought more than guns and other goods with them when they landed on North American soil. More potent by far than muskets were the microbes, teeming invisible warriors in the form of smallpox, diphtheria, influenza, cholera, measles and the like. The epidemics spawned by the continuous contact with the French were devastating. The people with no immunity and with only the flimsiest protection from the elements were helpless. Nomads who were constantly on the move carried it from area to area, from region to region, from great watershed to great watershed. The invincible stormtroops decimated the Native peoples.. The mortality rates resulted in the death of half their population lost in the span of 30 years or so. This was also a period of extreme hardship when the Iroquois contemptuously labelled them with the epithet "dog-eaters."[*****]

It was during this period when the Hurons were weakened by smallpox and other diseases that the League of the Iroquois decided to launch a determined attack on Huron settlements. Despite the fact that the forces to the north still outnumbered them, they felt this was the time to act. Their scouts had revealled that the Hurons were weak tactically since they failed to maintain a strong fighting force in any single strategic point. The Iroquois chose this time to attack for several reasons: they were convinced that the Iroquois unity had to be established or its opponents destroyed and they recognized that trade was becoming all-important and resented the Huron's dominence in this regard. Since their own lands did not produce enough furs they feared other nations would soon outstrip them in wealth and firepower.

In 1648 they were ready to strike. They sent out word that all tribes not allied with the League must consider the consequences. By the time the astounded Hurons received this word the Iroquois were upon them. No longer satisfied merely to secure booty and a few captives, the Iroquois decided to destroy their opponents. The Hurons suffered a series of crushing defeats and these setbacks resulted in them abandoning and burning their villages and taking refuge elsewhere. In a single year the great Huron Nation ceased to exist. With the Huron no longer a force to be feared the Iroquois then destroyed the Tobacco nation for harbouring Hurons who had fled to their lands. Because they were always quick to avenge a real or imagined insult, the Iroquois next attacked the Neutrals who suffered the same fate. The Senecas attacked their villages because the Neutrals had earlier allowed a Seneca brave to be captured by the Petun in Neutral territory. It was charged too that the Neutrals were in violation of their neutrality because they were holding large numbers of Huron refugees as prisoners. The few from both confederacies who survived the onslaught were absorbed by the Senecas. Instead of returning to their homes as they normally did following a fight, the Iroquois spent the winter in southeastern Ontario and in early spring renewed their surprise attacks. Many of the Hurons were killed or carried away into captivity. Those remaining fled in all directions to the Tobacco, the Neutrals and the French. These unrelenting raids scattered the Hurons far and wide, many fleeing and more being voluntarily absorbed by the Iroquois.

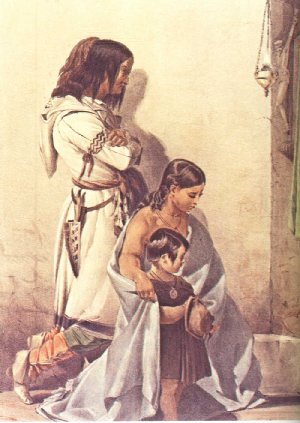

|

|

Huron Survivors Assisted by the French |

[*]So the London Times on September 14, 1829 mourned the passing of not just the individual Beothuk Indian Shanawdithit but the entire Beothuk culture that vanished from the Earth. [**] From the A Brief History/ Aboriginal Peoples, CBC News On Line, June 21, 2005

[***] 1st Corinthians 14, 10-11. [****] Jacques Cartier used the word tomahawk for hatchet but did not state that it was employed in combat. A century later another European speaks of the Mohawk using "weapons of war such as bows and arrows, stone axes and clap hammers." [*****] The source of this figure is "Indians of Canada" written in 1960 by Diamond Jenness, a highly esteemed expert on Indians of Canada for the National Museum of Canada. Another source, Stolen Continents, written in 1992 by Ronald Wright states that there might have been "several hundred thousand before the great pandemic of the 1520 and maybe only 75,000 a century later." [******] Archeological digs near Penetanguishene revealled during this period only small amounts of corn and a high percentage of dog bone and evidence that the people were eating bark, leather blankets and anything else organic. There were also signs of a plague expidemic and of much ceremony, undoubtedly an attempt to dispel the pestilence and bring on better times.Copyright © 2013 Website Administrator