foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

LOUIS DE BUADE, COMTE FRONTENAC

History is the chronicle of famous men.

On June 28, 1672 Louis de Buade, Comte Frontenac, Governor General of New France, sailed from La Rochelle to take up his position as governor of New France. The new governor was one of the more turbulent and influential figures in Canadian history. Unfortuately, we have no idea what he looked like because a portrait that would have left Frontenac's face for history does not exist. None is known and no one who knew him ever gave any hint as to his physical appearance.

|

|

Comte Frontenac |

Frontenac entered the French army while in his teens and was commissioned a colonel in the Normandie Regiment. He provided cannon fodder in Louis XIV's wars and while commanding the regiment his right arm was crippled and to compensate him for this injury he was created a brigadier. He was an excessively vain person who was quick to take offense. Like so many of his class Frontenac's life style was extravagant and he lived well beyond his means. As a result he became encumbered with debt and was forced to relinquish his colonelcy to pay off a portion of what he owed. The fact that Frontenac was a seasoned soldier was all-important at a time when France's colony was at risk from the ever-present English.

Frontenac would have functioned very well in the cloak and dagger age of the Three Musketeers for he was a member of the old nobility with the sword. Despite his all too evident faults Frontenac was possessed of great personal charm. While it was not easily detectable in his written documents, without it his career is difficult if not impossible to explain. The feudal aristocracy also served as figureheads in the provinces like New France. Frontenac received his appointment as governor general in 1672. While compensation for the position was limited, it relieved him of the necessity of paying off his creditors for while he held it, they could not seize his properties.

The paths of Frontenac and the "incomparable intendant" Jean Talon, who left the colony for good in 1672, crossed paths only briefly but the colony over which Frontenac began his rule as governor had been created largely by the intelligence and toil of Talon. His remarkable mind conceived ideas and just as rapidly realized them. Already Frontenac had seen Talon's dream and like Talon Frontenac was intrigued by exploration. The wilderness possessed him utterly and he carried on the Western policy which Talon had launched.

|

|

Jean Talon |

While his explorers were descending the Mississippi Frontenac grew restless in Quebec and gazing longingly upon the St. Lawrence he decided to follow it westward. He realized how important a French fort would be on Lake Ontario and decided to set out and find an appropriate place for it. Time was of the essence since the Iroquois were being stirred up by their powerful English neighbours who were also negotiating with the Natives for the exchange of goods for furs at a meeting place to be located at the entrance to Lake Ontario.

Frontenac realized how important appearances were to the Aboriginals and he proceeded to collect an impressive number of the best officers of the country and a fleet of canoes to accompany him. In order to calm any alarms his expedition might raise among the Aboriginals, he could think of no better person to precede him and announce his upcoming peaceful visit than one of the best qualified officers of the colony, Robert Cavalier, Sieur de La Salle. , La Salle, a brave, young explorer, was instructed to invite delegations from all the tribes of the area to meet with Frontenac and he succeeded in persuading the suspicious Iroquois to meet the Governor at Cataracqui. La recommended this location to Frontenac as a good one for the fort the Governor intended to have constructed.

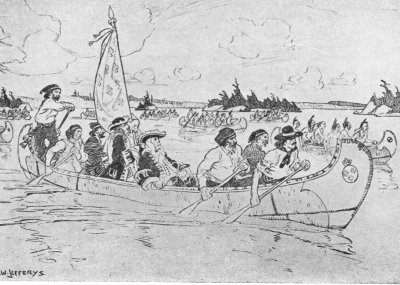

On June 29, 1673 Frontenac set out from Montreal on his journey up the St. Lawrence. His flotilla consisted of 400 men, 120 canoes and two bateaux or flat-bottomed boats painted in brilliant colours carrying a couple of cannons.

|

|

Frontenac on the way to Cataraqui, 1673 |

On July 12th they sighted Lake Ontario where Frontenac halted the entourage to arrange an impressive entrance. The company washed the stains of travel from their persons and dressed in their best. Natives accompanying the party painted themselves and decked their hair with feathers. The voyageurs donned their gayest shashes. Then bright with the colour and sheen of silk, velvet, ribbons, lace and gold braid, the flashing paddles dipping in time to the blare of trumpets, the roll of drums and the thunder of cannon the procession moved forward over the blue waters of the lake. Piloted by an Iroquois canoe that came out to meet them the French were conducted to the mouth of the Cataracqui River where the city of Kingson now stands. All the while on the shore Natives gathered and watched in wondering admiration the brilliant spectacle.

Frontenac described the scene in a lengthy letter to Colbert. "Soon they decided to send to me the captains of the five nations with their orator named Toronteshati who is the most skilful and the most experienced among them to present their compliments. These having been answered they offered to conduct me to the mouth of the river Katarakoui and to the cove which they assured me would be suitable for a camp."

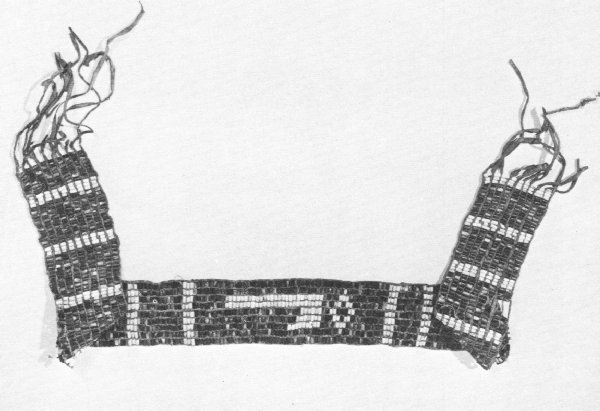

Frontenac was impressed with "the pleasantest harbour" at Cataraqui where he found land fit for cultivation, timber, a sheltered harbour and a good look-out on a point. He agreed with La Salle that a better place could not be found to build his fort. After smoking silently with the Natives for some time, wampum belts were presented representing the following tribes: the Onondagas, the Mohawks, the Oneidas, the Cayugas and the Senecas. At the end of public addresses Frontenac presented each nation with guns, wine and brandy, while biscuits, prunes and raisins were given to the women.

|

|

Frontenac treats with the Iroquois at Cataraqui (Kingston) in 1673 and extends the hand of friendship to their chief. |

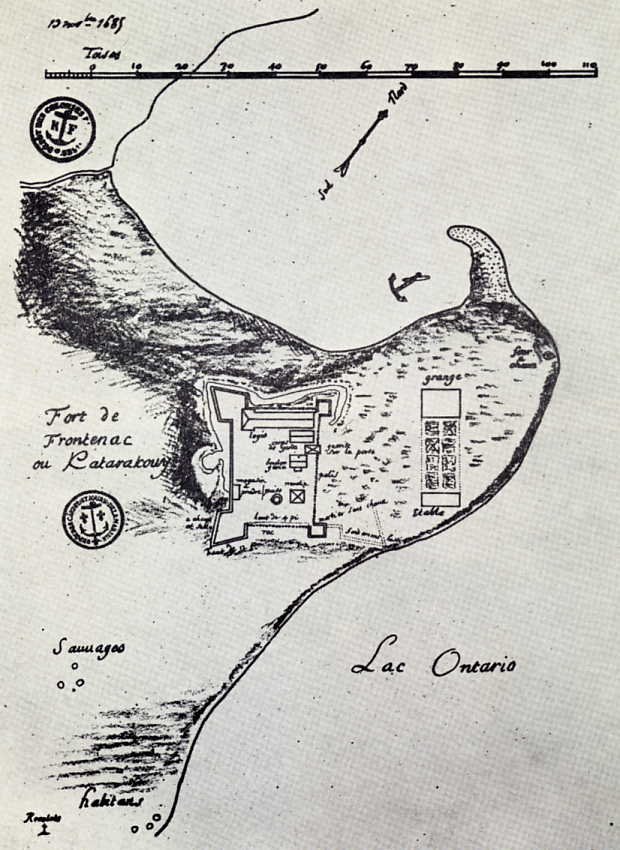

By evening the site was approved and plans made for the fort's construction. After a meal and following approval of the Native chiefs, the order was given to begin felling trees. According to Frontenac, "The zeal and diligence with which everyone worked to build the fort was inconceivable." The site for the fort was nearly cleared and before long a building 14 metres long and 6 metres feet wide was constructed. In six days it was enclosed and put into a state of defence. "All this gave the Natives an understanding of the formidable power of the King and the vigorous industry of the French and I had no difficulty making them appreciate my proposals and convincing them to come to Kararakoui to seek their necessaries where I promised them the best prices. I also expected them to give me six of their girls and three of their boys of the age of 8 or 9 to be instructed in the faith and taught to read and write and even some trades.

|

|

Fort Frontenac at Cataracqui (now Kingston) |

Frontenac camped at Cataraqui near the eastern end of Lake Ontario where he received France's old enemies with firmness, friendliness and bluster. Frontenac delivered a diatribe on the power of the king and while he gave promises of royal protection, he cautioned about the consequences of other alternatives. The proud, vigorous old soldier knew instinctively how to deal with the Natives by alternating presents and threats. Under no other governor was the prestige of the French higher with their Iroquois enemies. The Iroquois liked and feared this kind of man and their moccasin telegraph carried throughout the whole interior the legend of the great Onontio,their name for Frontenac.[*] Frontenac reported proudly to Colbert about his success with the Natives and to reinforce what his diplomacy had won he informed Colbert that he had sent carpenter up to Fort Frontenac to have a boat built to sail on the lake so that France would control the fur trade on both shores.

Duchesneau, the intendant at the time, and Bishop Laval both opposed Frontenac's preoccupation with fostering of the fur trade by expanding the reach of France and used every means to undermine his authority. They called for a limitation of the numbers of coureurs de bois blazing new trails all over the west. As far at they were concerned, these runners-of-the-woods robbed the settlements of farmers and they joined forces to fight Frontenac and his expansionist ambitions.

A whole culture grew up around the fur trade business. The coureurs de bois, the working men of the woods, learned their skills from the Natives and worked along side them. When young men came of age they left the villages and strip farms along the St.Lawrence and ran away to the river to work on the Great Trace, the name given to ever-westward route taken by the big canoes. Little but lithe and strong, the coureurs were canoe jockeys who paddled and portaged along the rivers that wound like capillaries throughout the country. They returned from the wilds with furs bundled into bales weighing 27 kilograms each. Known as a 'piece,' each bale was fitted with straps for backpacking at a canter along a portage. Liquor had become an essential article in the fur trade, but Bishop Laval demanded an end to the baneful influence of brandy traffic traded by the French for furs. However, if the French had no brandy to offer, the English got the best furs for their rum, so Frontenac persisted in using it in the face of opposition from Laval. The unrestrained growth of the French fur traders also aroused the Iroquois and their English allies who complained bitterly,"'Tis a very hard thing that all Countryes a Frenchman walks over in America must belong to them."

It was not only the fur trade over which the two officials fought. Duchesneau and Frontenac found they could fight over anything. In letters to the government in France they accused each other of taking an illicit profit from the fur trade. Their infighting got out of hand and reached the point where their supporters attacked each other in the streets. Frontenac was cautioned by Colbert that there were many in New France who were complaining about his autocratic and even tyrannical behaviour. Even the king warned the high-handed governor "New France runs the risk of being completely destroyed unless you alter both your conduct and your principles." The following year he was told he would be recalled unless he changed his ways. Frontenac proved unwilling to conform and finally in frustration he was and Duchesneau were ordered to return to France. Frontenac, recalled in disgrace, seemed to be a ruined man.

To friend and foe alike Frontenac's recall at sixty-two seemed the definite, humiliating close to a career. While his domestic squabbles with Duchesneau had seriously upset the administration of the colony, Frontenac's presence had ensured there was no war in his first term of office. Despite his contentious behaviour Canada could thank Frontenac for keeping the Iroquois at arm's length. He did this with firmness, sympathy and fair-dealing. His arrogant and dogmatic manner with those who were his equal disappeared when he came into contact with Natives. With them he was never intolerant or narrow-minded and the Iroquois, who were always good judges of character, were impressed by his manner and demeanour. They knew that behind any of his displays there was always his power. Frontenac's strength was evident and citical to all but for a time it was forgotten.

As more and more furs found their way to New Yor, the supremacy of the French system on the St. Lawrence was increasingly threatened. When war once again broke out between France and England in 1688, the latter rapidly became a rival imperial system. As the Iroquois took advantage of this conflict they became more daring. Their ferocity culminated in an attack on Lachine which led to the massacre of its inhabitants under the very walls of the French stronghold of Montreal. During this savage assault, it was declared that those who fell from the tomahawk were the most fortunate. The Lachine disaster threatened the colony's lifeline. Frontenac's successor lacked both his skill and fierce aggressiveness in dealing with the Natives and the crisis led to Frontenac's recall to New France in 1689.

The mist of time obscures events so they cannont be known with certaintly, but it is a good bet that the mercurial-tempered Frontenac fumed at the failure of his successors to keep the colony secure. The Iroquois had become murderously bold during his absence as demonstrated by the massacre at La Chine. According to a local bishop the terror at the time had been so indescribable that ever since its occurrence the simple appearance of a few Natives put the whole neighbourhood to flight. Frontenac's faint-hearted successor had abandoned Forts Niagara and Frontenac and English forces from New York, New England and Virginia were now pressing hard upon the established realms of the French king. Louis XIV's instructions to Frontenac were expressed very simply: "I send you back to Canada where I expect you to serve me as well as you did before." The entire population of the country greeted him as a deliverer.

The Iroquois believed that Onontio had lost his power. They were to learn differently. New France faced a crisis that called forth all the courage the seigneurs and habitants could muster and they rose to the demands of the hour. The frontiersmen were fighters and no braver breed of warriors answered the call of Frontenac. . The French waged war against the English from Albany and New York and at the same time fought off the ferocious attacks on the colony by the Iroquois.

Frontenac's first task was to re-take and rebuild Fort Frontenac which his predecessor had abandoned as indefensible against the Iroquois attackers. With an army of some three thousand men Frontenac proceeded re-occupy Fort Frontenac in July 1696. After its restoration he launched an attack with some two thousand men against the Onondagas and the Oneidas. The seventy-four year old Count was borne in a chair between the two divisions. Nothing was left undestroyed in their country by the invading French forces. Carrying the war into their own country, he struck them hard and often. The Oneidas and the Onondagas began to sue for peace and shortly thereafter four of the Iroquois nations - the Mohawks being the exception - sent deputies to Quebec to start peace negotiations.

French-English border raids and reprisals became an established pattern until New England and New York decided to up the ante by attempting an invasion of Canada. Frontenac believed that nothing short of some swift success at arms would awe the Iroquois and rebuild morale along the St. Lawrence. He settled for a series of guerrilla raids into the English-American colonies and his three raiding brigades achieved his aims. The legacy of these shocking French raids roused a deep enmity for and a strong suspicion of anything French in the northernmost of the 13 Colonies. Two raids were planned in retaliation.

The first of these was an English invasion by a land force sent from Albany to attack Montreal. When it collapsed in confusion by 1690 the French colony was motivated by fresh hope. The second assault was by sea. Command of the naval exedition had been given to Sir William Phips who managed to bring the ships involved from Boston to Quebec. In his 44-gun battleship, Six Friends, and with his new rank as major general Phips was ready to sweep the French completely from North America. "The plan is well formed," he said, "and I am the best man in Boston to handle it." He was hopeful that the mere sight of so great a fighting force would compel surrender.

Phips sent a subaltern to Frontenac under the protection of a white flag to demand the French surrender. The messenger was kept blindfolded until he was ushered into the reception room of the chateau. When the blindfold was removed an unexpected sight greeted him. Hoping to do a little bit of intimidating himself the aging governor had arranged an impressive spectacle using costume, colour, demeanour and display. The subaltern, who blinked in the sudden light and at the brilliant assembly, found himself surrounded by dignified deputies in brightly coloured raiments of finest lace and richest silk with their swords ready to be unsheathed at the slightest pretext.

|

|

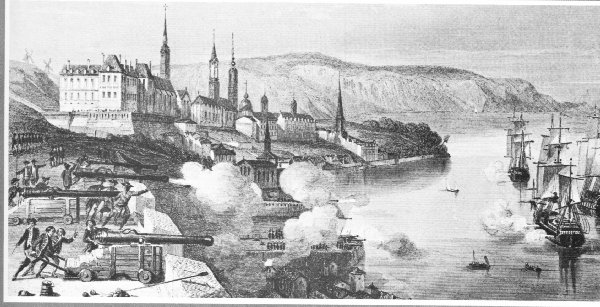

Governor Frontenac - A Flourish for Phips |

Nervously saluting the governor the subaltern handed a letter to Count Frontenac who passed it to an interpreter. It was an ultimatum demanding the surrender of "all your forts and castles undemolished and the King's and other stores unimbezzled, together with a surrender of your persons and estates. You may expect mercy from me. Your answer is required in an hour." The messagner drew a watch from his pocket and handed it to the governor. "It is now ten o'clock. The answer must be had before eleven." This audacious demand was greeted by angry, outraged shouts which Frontenac silenced with a raised hand. In a calm voice Frontenac said he would not keep the messenger waiting for as long as an hour and curtly refused the terms. When the messenger asked whether he would be so kind as to put his answer in writing, Frontenac famously replied: "I will answer your general by the mouths of my cannons and muskets."

|

|

"By the mouths of my Cannons!" |

The ball was now in Phips' court. He ordered his ships to begin their bombardment. He fired 1500 rounds in a useless cannonade against the cliffs and walls of the Upper Town without effect. Frontenac outgunned the British, his cannon fire from the ramparts high on Cape Diamond forcing them to turned away. Finally, with his fleet badly riddled by fire from the batteries on the rock, Phips decided that discretion was the better part of valour and sailed away. Phips said his lack of success was due to "the smallpox and the fever which increased so fast among he men that it delayed the siege until the weather grew so extremely cold that no further progress could be made."

Frontenac had gambled and won. New France had met and repelled the invasion. Convinced that only audacity would restore French prestige, Frontenac had risked the consquences of a direct attack on the New England colonies and then had successfully countered their angry reprisals. The most precious trophy was the flag of Phip's ship which was shot from the ramparts, knocked into the river, rescued and brought ashore in triumph. Shouts of rejoicing followed. Frontenac had done what he had been sent to do. The white and the gold still floated about the Chateau of St. Louis.

|

|

Wampum Belt |

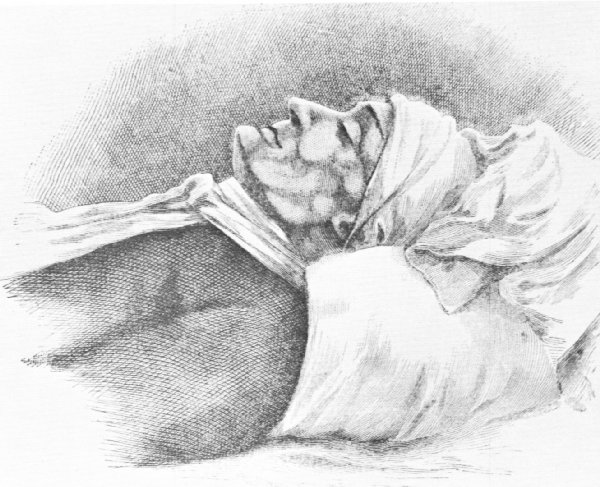

In poor health and suffering from asthma durng the last few weeks of autumn in 1698, Frontenac tried to sleep propped up in an armchair but his strength began to ebb. By mid-November he knew the end was near. On the 28th of November at the age of seventy-eight death came to the old governor. Frontenac died at the Chateau St. Louis in Quebec and was buried in the church of the Recollets of Quebec. Fearless, forceful, dynamic and dedicated - that is the Frontenac of lore and legend. Some challenge that engraving of the governor. Frontenac was a gifted and prolific writer and his version of all events contrived to make everything rebound to the greater glory of Frontenac. His colourful accounts pleased the reading public. Historians who subscribe to the "great man" theory of history were charmed by the hero and his escapades, but when his versions of events are checked against all available evidence from various other sources distortions sometimes become apparent.

Nevertheless, Frontenac was a dominant figure over a most difficult period in the colony's history. If his good traits are set against his bad, he would be characterized in the former column as being brave, steadfast, daring, ambitious and far-sighted and one of the greatest of Canadian governors and lieutenant generals. In the latter category he would be seen to be prodigal, boastful, haughty, unfair in argument and ruthless in war. However, as he aged his higher qualities became more conspicuous as his vision cleared and his vanities fell away.

"So far as Frontenac is concerned it is sufficient to say that under his command New France was not conquered and the Iroquois attackers were finally defeated." In the hour of trial and tribulation when the fate of New France hung in the balance and its survival rested upon his shoulders, Frontenac was never found wanting. He dreamt dreans of France's mighty empire based on the energy and exploration of hardy discoverers one of whom was La Salle.

[*] This nickname served for all governors of the French regime. Literally it meant Great Mountain. (Io:great; Onont: mountain) Because the natives could not pronounce French names they substituted words used by them which had some relationship either to the sound of French names or to their meaning. |

|

Frontenac - the Old Warrior At Rest{Forts of Canada} |

Copyright © 2013 Website Administrator