foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

LA SALLE

History is the actual drama of actual men who are no more.

France, which had become the first military power of Europe, stood on the threshold of its greatest age. Its sovereign, the Sun King, Louis XIV, was France's greatest monarch. He certainly thought so for without a shred of modesty Louis proclaimed, "The State! I am the State." He was young, strong, wise and ambitious and during this proud and prosperous period for France he was determined to construct a mighty realm by creating an empire beyond the Atlantic.

|

|

Louis XIV |

|

|

Coat of Arms of France 1728 |

Je me souviens -I remember.

This is no empty watchword. No true understanding of French Canada is possible without a realization of what its history - one of the most colourful for its span of years of any human record - means to French Canadians. Above all the adage means that Quebeckers remember the heroic glories of the French period in America, a time so adventurous and romantic there was no need for any added compensating colouring.

It was during this period of enterprising trailblazers that an individual arrived from France who is considered by many to be the greatest of all French explorers - the brilliant, intrepid Rene-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle. This strange, fascinating man who arrived in the New World in 1667 felt fate had beckoned him to explore this colossal continent. A strange determined man who lived his life completely in service to his dream. La Salle is a figure who continues to fascinate.

|

|

René-Robert Cavelier, sieur de La Salle, engraving. |

René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle was born at Rouen in Normandy on the twenty-first of November, 1643. He came from a wealthy, middle-class family. La Salle was an apt pupil who from the eariest years evinced an eagerness for travel and adventure. At the age of fifteen he was enrolled in the Jesuit noviciate of Rouen and he took his vows in 1660. Five years later he asked to be sent abroad as a missionary, however, he lost his vocation and invoked "moral weaknesses" as his reason for asking to be released from his vows. He was finally freed from his commitment and came to Canada in 1666. He had a domineering and obstinate temper which chafed under discipline and rebellious to authority, he was resolved to yield to no obstacle.The boy was father to the man and these qualities were to place his name high on the roll of fame and to add an empire to the dominions of Louis XIV. He gathered information from every source and prepared for his life work. This was the character whose career would eventually lead La Salle to explore the lands south of Lakes Ontario and Erie in 1697-169=80.

The existence of a great river to the southwest was acknowledged but it was known only through vague reports. La Salle was to discover the mouth of what was the "Father of Waters," the great Mississippi River.

"Faced with the North American woodlands, a European had two choices. He could look at it as a place to be avoided, a howling wasteland full of very dangerous human beings or he could look at as a realm of beautiful, hard, unforgiving freedom which was La Salle's way."

|

|

Cavalier de La Salle - The Visionary |

Slightly under six feet tall, La Salle gave evidence of great physical strength in the broadness of his shoulders and the thickness of his limbs. His long, black, shiny hair brushing the nape of his sturdy neck was not unlike that of a coureur de bois who had lived in the wilderness for a long period. His sun-darkened face was narrow, his nose slightly convex and long with firm, straight lips. Everything about him was relatively unremarkable except his eyes. Large and intensely dark they peered out from under heavy slanting brows said to be much like those of a bloodhound. Eyes reflect the emotions and the fires in his alternately smouldered and flamed as "he became enraptured by some private hope, engrossed by the prospects inherent in some dream or angered by the adversities of a situation he had to face." Let his story sweep you away.

|

|

Rene Robert Cavalier de La Salle |

Filled with vibrant energy and dreams of his own greatness, La Salle listened in wonder to tales told by friendly Seneca braves of the great rivers that flowed into the Vermilion Sea. The Vermilion Sea! La Salle's heart quickened at the name that evoked in his imagination the warm waters of the Orient. The lure of the west was irresistable for he saw in it great new dominions for the grandeur of France. His plan was to hold and control the Great Lakes with a series of fortified posts at stategic points and using these as a base explore southward towards New Spain.

The Beautiful River (the Ohio) flowed due west. La Salle was uncertain whether this was another name for the Mississippi or whether the stream flowed into the Father of Waters, the Native name for the Mississippi. On one point the Senecas were very positive: the Beautiful River flowed finally into the Vermilion Sea. The tale of the Father of Waters seized his imagination and gave him no peace of mind. To see and follow it wherever it led was the task of all tasks that called him constantly. It drew him finally like a lodestone across lakes, rivers and endless forests to find and follow the mighty Mississippi to its end and ultimately to his.

|

|

La Salle Sets Off For the Mississippi River |

La Salle set out on July 6, 1669. He was gone for two years and there is considerable doubt as to where he actually went and what he did. Some historians suggest that he went as far as the junction with the Mississippi. La Salle is supposed to have recorded some years later that he reached the Ohio and followed it to a waterfall he described as fort haut that made it impossible to proceed. Unfortunately these notes were lost. Other writers say he reached the Mississippi but La Salle made no such claim. That honour belonged to two daring and dauntless explorers, Louis Joliet and Father Pierre Marquette, who began their search for the Mississippi on May 17, 1672. One month later they followed the Wisconsin River until it joined a new river which turned out to be the Mississippi. They followed the course of the great river until they reached the mouth of the Arkansas river from where they decided to turn back. The mighty stream did not flow eastword to the Vermilion Sea but south to the Gulf of Mexico cutting the continent in half.

When La Salle returned in 1672 important changes had taken place in the colony. A new governor of Canada, Count Frontenac, had been appointed. Frontenac was dedicated to exploration and was immediately interested when he learned of the ambitious young man with a passion for discoveries and with experience and wide knowledge of the western tribes. When Frontenac decided to do a little exploring himself, he could think of no better person to precede him and announce to the Natives his upcoming visit to the area. La Salle persuaded the suspicious Iroquois to meet the Governor at Cataracqui which he recommended to Frontenac as a good location for the fort the Governor intended to have constructed.

|

|

Frontenac treats with the Iroquois at Cataraqui (Kingston) |

|

|

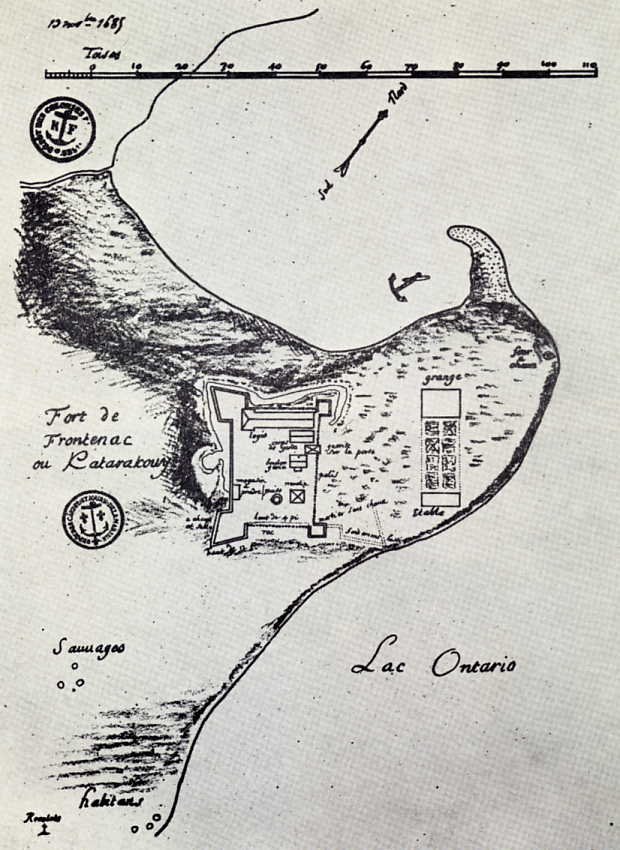

Fort Frontenac at Cataracqui (now Kingston) |

The turning point in La Salle's career really came with the arrival of Frontenac. La Salle, the restless explorer and promoter, had recently returned from the wilds filled with wonder and numerous ways in which the west could be secured for France. It was not difficult for La Salle to fire up Frontenac, a kindred trail blazer who shared La Salle's belief that a western empire and a great deal of wealth could be won by seizing control of the Mississippi. Frontenac was a kindred spirit and an alliance was quickly formed between the two men. La Salle like Frontenac had extravagant ideas and was not afraid act on them.

When Louis XIV appointed Jean Talon intendent of New France, he ordered him to "carry war to their the firesides of the Iroquois in order totally to exterminate" the French colony's perpetual and irreconcilable enemies. Frontenac took up this task and launched frequent attacks against the Iroquois and their English allies. While his work as a warrior was important, Frontenac was also a chief architect of French expansion in North America. He sought to monopolize the fur trade of the lower Great Lakes and the territories to the south by building a string of "western posts" that would serve also as forts to prevent English expansion into the west.

Frontenac granted La Salle Fort Cataraqui which La Salle promptly renamed Fort Frontenac, the oldest military establishment in Ontario. To ensure that the king would confirm his new seigneury, La Salle left for France> he carried with him a warm testimonial from Frontenac to Colbert, the king's chief minister. "I can but recommend to you monseigneur, Sieur de La Salle. He is a brilliant and intelligent man and the most capable here that I know for the enterprises and discoveries to which he could be assigned. He has a very thorough knowledge of the state of the country. a fact that will be revealed to you should you find it convenient to receive him for a few minutes." Colbert was impressed with La Salle and recommended that the king confirm La Salle's seigneury. Because of concern among the French regarding England's continuing attempts to make inroads into the French fur trade, Fort Frontenac served to discourage English ambitions in this area and to provide a secure base for French interests.

|

|

Jean Bapiste Colbert |

La Salle returned to Quebec and shortly thereafter departed for Cataracqui to carry out the work he had promised Colbert he would complete. He sailed to Cataraqui with canoes loaded with goods accompanied by soldiers, sailors, masons, carpenters, a blacksmith, an armourer and other tradesmen. Frontenac's flimsy fort of earth surrounded by a wooden palisade was transformed into a square with four bastions measuring 100 feet from one corner to the other. Constructed of hewn stone with a rampart twice as big as the first, it comprised a guardhouse, a barracks, a house for the officers, a well, a cow-house and a mill and bakery. Three walls were made of of masonary three feet thick and twelve feet high. The remaining side was constructed of wooden stakes. Ditches and a moat fifteen feet wide were dug around the fort.Fort Frontenac was a necessary step in the development of his vast and adventurous discoveries. One hundred acres of land were cleared and crops planted. By combining forces, Frontenac and La Salle became wealthy at the expense of business men at Montreal, because of their monopoly on the fur trade.

|

|

Plan of Fort Frontenac 1738 |

|

|

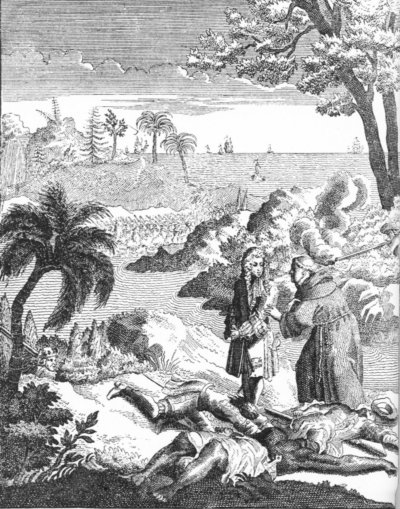

La Salle inspects Fort Frontenac under construction in 1673. |

Despite being strengthened with masonary walls, Fort Frontenac was vulnerable, because it was located on low ground and could be fired on from the heights to the west or from Point Henry (site of Fort Henry) on the east. Under a British force led by John Bradstreet, it was captured from the French in August 1758.

At different intervals, La Salle was to spend less than three years in his seigneury, where he could have remained and enjoyed a revenue of twenty-five thousand livres a year. He preferred enterprises "more perilous and precarious and more worthy of Honour."

Once the work on Fort Frontenac was completed, La Salle returned to Paris where his report on the work on that fort was well received. As a result of La Salle's success there, Colbert on May 12, 1678 granted him permission to carry out explorations on the western parts of North America between New France, Florida and Mexico and to "build forts in places where you think them necessary."

Since time began, the only vessels on the lake had been canoes. That changed in 1678 when the ambitious Chevalier de la Salle decided to build a "barque" above the falls. Detractors wondered at this weirdness and declared him "fit and ready for the madhouse." Late in December La Salle and Henry Tonty, a faithful friend, left Fort Frontenac "in a great Barque." Despite nearly being wrecked by their pilot on Christmas Eve off the Bay of Quinte, they landed at the mouth of the Genesee River. La Salle continued overland to a large settlement of Senecas, where he persuaded the Natives to allow him to transport across their territory his supplies and equipment by portaging around the great cataract so that he could build a vessel above the falls. Meanwhile the pilot of the barque continued along the south coast of Lake Ontario, where with all its precious cargo, it was lost in a storm and only the cables and anchors were saved. It was thought by some, that the pilot had been influenced by enemies of La Salle, for whom fate seemed to take delight in shattering his dreams.

Learning of this catastrophe La Salle returned through forest, field and over ice to Fort Frontenac, a distance of some 250 miles, where he obtained additional equipment and returned to the construction site. Despite frequent unfortunate mishaps and many unfavourable circumstances, the boat was finally built largely as a result of the determined efforts of Henry Tonty, known to the Natives as Iron Hand because he had a metal right hand to replace one lost fighting in France. The vessel was christened Griffon in honour of Frontenac whose coat-of-arms contained a griffon.

|

|

Detail from the building of the Griffon, published in 1704 |

|

|

Griffon: A mythical animal typically having the head, forepart and wings of an eagle and the body, hind legs and tail of a lion. |

|

|

The Griffon |

|

|

Griffon |

The Griffon, the first vessel to sail the Upper Great Lakes, was a fine, ship-shape bark 18 metres long and 4.8 metres wide with two masts and weighing some forty-five tons burden. Its construction at Cuyaga Creek, a tributary of the Niagara River several kilometres above the great cataract, was nothing short of miraculous. Father Louis Hennepin, a bearded Recollet priest dressed in a hooded, brown-grey robe, gave the blessing as the Natives looked on in amazed wonderment placing "four fingers over their mouths in a sign of stupefaction." Here, indeed, was a monster that mounted five cannons and had an anchor so heavy it took four men to drag it.

Although the vessel, which was launched on August 7, 1679, was several kilometres above the falls, the prospect of the craft being carried over the cataract by the current that "shot past with the speed of an arrow" was terrifying to the crew. La Salle's irresistable strength, authority and intelligence overrode their doubts and timidity. The arms, trade goods and provisions were stored in the hold and with twenty-five people on board having little to lose but their debts they set sail, their departure timed when the wind was stronger than the current. With tow ropes attached to trees along the shore and after a day of sweat and strain they slowly entered the calm waters of the lake.

This first sail boat ever to plough Lake Erie and the upper lakes astounded the Natives who believed it was moving by some supernatural force. With a fresh breeze filling its snowy new canvas and the white and gold fleur-de-lis flying majestically at her stern, the magic vessel disappeared into the setting sun. Sailing conditions were favourable and they enjoyed a pleasant passage through the sparkling waters of Lake Erie, covering more than one hundred leagues in three days. On the morning of the fourth day the Griffon passed through the Detroit River and into Lake St. Clair.

On Lake Huron a violent storm battered the bark whose creakings and groaning grew so alarming that the crew threw themselves on their knees to ask God's help. The wind finally calmed and the fearful travellers found anchorage at Michilimackinac off Point St. Ignace in the Straits of Mackinac that join Lake Huron and Lake Michigan. A week later the Griffin entered Lake Michigan and docked at Washington Island off the mouth of Green Bay where men whom La Salle had sent earlier had accumulated a treasure-trove of furs.

Good fortune had finally favoured La Salle. He was about to free himself of his rapidly mounting debts. He sent the Griffin loaded with pelts back to the Niagara River where a boat from Fort Frontenac would pick them up. With 12 thousand livre of pelts in his creditors' hands the pressure on him would ease temporarilly. La Salle then directed that the Griffon "with all imaginable speed join us toward the southern parts of the Lake where we should stay for them among the Illinois." On September 18 the ship laden with furs sailed eastward. The following day La Salle with carpenters' tools, a forge, some trade goods and 14 men commenced paddling towards the foot of Lake Michigan. The 'magic' vessel vanished with no one knowing when, where or why. [*]

|

|

La Salle Awaiting the Return of the Griffon |

Much of what we know of this period is attributable to Father Hennepin. In his book A New Discovery of A Vast Country in America. written in 1698 Father Hennepin wrote, "I was from my infancy very fond of travelling and my natural curiosity induced me to visit many parts of Europe." Hennepin's interest in touring and trekking was put to good use in North America where he experienced numerous trips, trials and tribulations as he followed La Salle about the continent. He became famous for his wilderness pursuits and infamous as a liar for his accounts were often filled with fabrication.

On the 6th of December 1678 a small group of Frenchmen struggled through the deep snow that crowned the cliffs of the Niagara gorge. Far below the foaming rapids raced towards the the whirlpool around which the explorers had circled. In the stillness of the winter woods they could hear the distant roar and as they drew closer to the tumult they saw clouds of mist mounting into the air. Natives had told them of this wonder but nothing prepared them for the sight of the great semi-circled cataract over which emerald-green water thundered shaking the very ground on which they stood staring in amazement. One of the awed onlookers was Father Hennepin whose drawing while out of proportion is the very first graphic picture of the falls as it existed then. Hennepin described the scene as "the most beautiful and altogether the most terrifying waterfall in the universe."

Hennepin was a most fashionable author of the time whose works of which there were no fewer than 46 editions, were read with eager fascination. He was not always careful about details, but he described perceptively the Indian tribes, their way of life, their customs and their beliefs. Because his records were lost La Salle left no personal account to provide a clear signpost to the inner forces that energized him. While Hennepin oftimes took latitude with the truth, he did share in the discoveries made in New France and succeeded in making them known throughout Europe. His accounts have historical importance because they offer a partial glimpse, a distant mirror into La Salle's life and career.

|

|

Niagara Falls 1695 |

|

|

Hennepin At Niagara Falls, 1678 |

|

|

Title Page of Father Hennepin's Account of Life in the Wilds of North America |

On the 29th of February, 1680 La Salle and others set out in search of the Griffon. Part of their journey was on foot through woods "so thickly intertwined with briars and thorns that in the two and a half days he and his men had their clothes torn to shreds and their faces so slashed and covered with blood they were unrecognizable." In April they reached Niagara where they learned of the loss of the Griffon and another vessel which was bringing La Salle 20,000 francs worth of goods. When La Salle learned of his losses, a calamity that would have crushed most men, he lost no time in lamentations. Nothing daunted he resolved to strike out toward the Mississippi and resumed his unflagging search for elusive glory and greatness.

La Salle embarked with thirty men and eight canoes. During a three year period he established forts hundreds of miles apart on Lake Ontario, Lake Erie and Lake Michigan, as well as overseeing the construction of forts and trading posts on the Illinois River. His plan was to seize and hold the Mississippi, Ohio, and Missouri waterways and so confine the land-hungry English colonists to the Atantic coast. This might have worked had the French court been prepared to invest money and men in military and naval forces to defend their interests in North America. By building forts and maintaining strong native alliances through lavish gifts and other forms of compensation, France might have controlled the continent. The ultimate judgement of the King and his counsellors was that it cost too much to gain too little. Their decision doomed the French empire to defeat.

Father Marquette and Louis Joliet were the first Europeans to reach the Mississippi. It remained for La Salle and his party to follow the river to its mouth, a trip following the twists and turns of the Mississippi of more than 3500 miles. La Salle gave the signal for departure and as always started out in the lead striding with long steps over the marshy prairie. In April 1687 they new they had arrived near their journey's end when they drifted down the turbid current until the brackish water turned to brine and the breeze blew fresh salt air in their faces. They had reached the broad expanse of the great Gulf which opened before them "tossing its restless billows, limitless, voiceless, lonely as when born of chaos without a sail, without a sign of life." La Salle in a canoe coasted the marshy borders of the sea then landed and claimed all the land drained by the Mississippi and its tributaries for King Louis XIV.

An associate of La Salle's described their arrival at the mouth of the river.

In His Own Words

"Here we prepared a column and a cross and to the said column were affixed the arms of France with this inscription: 'Lois Le Grand, Roi de France et de Navarre, Regne: Le Neuvieme Avril, 1682.'

Then amid volleys of musketry and shouts of Vive le Roi, La Salle, clad in a scarlet cape trimmed in gold, declared in ringing tones that the territories had passed under the rule of the French crown. "In the name of the most high, mighty, invincible and victorious Prince, Louis the Great, by the Grace of God King of France and of Navarre, this ninth day of April, 1682.'

|

|

La Salle at the mouth of the Mississippi 1682 |

While the Indians looked on in wondering silence, the weather-beaten voyageurs joined their voices in the grand hymn, 'The banners of Heaven's King advance.' All arms were raised in the air as renewed shouts of Vive le Roi closed the ceremony. The whole of this vast region named Lousisiana which stretched limitlessly to the western horizon had been claimed for France. More importantly the mystery of the Mississippi had been solved.

La Salle had once again fulfilled the terms of his commission. He had taken five years to discover the western country and to build forts along his route. In spite of desertions, envy, calumny, hunger, robbery, Native opposition and fierce natural elements like wind, water, snow and ice, he had achieved his life-long dream of exploring the Mississippi down to the sea. He had succeeded in seizing for his sovereign an immense part of the North American continent. In his main post of Fort Frontenac he had a base for controlling the troublesome Iroquois and for maintaining good terms with other nations.

La Salle returned to Quebec and then to France where he convinced the king to finance a voyage to the Gulf of Mexico from where La Salle said he would sail up the Mississippi River and establish a trading post and fort from which to launch attacks on the Spaniards and eliminate Spain's dominance of South America. In order to convince the king of the success of this enterprise, La Salle agreed to falsify the geography of the Mississippi and had maps prepared that showed it some 1200 kilometres west of where it actually was.

Around the middle of December 1686, the French flotilla reached the entrance to the Gulf of Mexico and travelled east in search of the mouth of the Mississippi. By sailing along the northern coast of the Gulf they could not have missed it for no other river poured such a great flood into the Gulf and no other delta was comparable in size nor extended out further from the mainland. However, having nothing to guide them the little fleet took a course considerably south of the route that would have ensured their seeing the three-pronged mouth of the great river.

On the 28th of December they sighted land around a bay and La Salle thought at first they were located at the Mississippi. They had, in fact, mistakenly landed in Matagorda Bay near what is now the city of Houston, Texas, well west of the Mississippi's mouth. The ships became separated. One ran aground and the frustrated captain of another returned to France with his disgrunted crew. The remainder of the party including La Salle landed. Shortly thereafter they encountered hostile Natives who killed six of La Salle's best men. Days passed as they meandered aimlessly about with a worried La Salle well aware of how heavy the price their futile wanderings were in men and materials.

|

|

Routes of La Salle's Trips |

The expedition built a fort at the mouth of the Lavaca River and explored the area. In April 1686 they realized they were stranded in this strange, unpleasant place when their last remaining ship was wrecked. There was no letup in La Salle's misfortune for it followed to the very end. Violent arguments arose among disenchanted members of the expedition and shots were fired leaving three dead. Among those killed was La Salle's troublesome nephew, a violent, hot-tempered, disagreeable individual whose contemptuous attitude and often excessive rages triggered thoughts of deadly revenge.

La Salle, warned by sombre forebodings of tragedy, hastened to the scene of the crime. The murderers harboured strong spite and resentment against La Salle and decided they would have to cover up their crime by killing him too. "Where is my nephew?" La Salle demanded on meeting the men. Without doffing his hat or showing any other sign of respect, one of the men said with a wave of his hand, "Somewhere further along the stream." As La Salle was rebuking him for his insolence, a sharp report came from the edge of the trees an the great discoverer slumped down dead from a bullet to the brain. Stripped of all his clothes including his famous scarlet cloak, the tireless explorer was left to be devoured by wild animals. La Salle met his tragic fate on the 19th of March 1687 while attempting to establish a base for the conquest of the Spanish mines in Mexico.

So ended the stark, solitary life of a resolute, unflinching, nerveless, heroic individual who sacrificed everything in the service of ambition. Few tales excel those of La Salle's. His life was filled with exploit, enterprise and danger, all intermingled with mishap, mischance and misadventure. Despite adversity La Salle displayed a grim determination to succeed and the superhuman strength, tenacity and courage he called on throughout his life defies comparison.

|

|

The Murder of La Salle |

[*] The Griffon is thought to have foundered on its way down from the head of the Lakes. The crew was lost. It took nearly three hundred years for the fate of the vessel to be discovered. A little more than half a century ago, six skeletons were found in a cave on a Lake Huron Island. The crew of the Griffon had consisted of Pilot Luc as master, four sailors and a boy. Nearby the hull of a ship was found at the botton of the lake. This evidence seems to be reasonably conclusive, according to Thomas B. Costain, author of The White and The Gold.

Copyright © 2013 Website Administrator