foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

LA BELLE PROVINCE

History is above all else the creation and recording of heritage.

Je me souviens -I remember.

This is no empty watchword. No true understanding of French Canada is possible without a realization of what its history - one of the most colourful for its span of years of any human record - means to French Canadians. Above all the adage means that Quebeckers remember the heroic glories of the French period in America, a time so adventurous and romantic there was no need for any added compensating colouring.

Jacques Cartier, Champlain, La Salle, in a word France, opened up this land of fertile soil, healthy climate, lush forests, rich minerals, magnificent waterways and inexhaustible commerce. Canadian colonial troops won brilliant successes alongside the French soldiery against an enemy of superior numbers. French explorers constantly enlarged the French domain - in North America.

"We have had a glorious past. We have not been afraid to face the perils of the sea, the rigors of nature, the ferocity of the Aboriginals, the numerical superiority of hostile armies. We have carried the fleur-de-lis from Quebec to New Orleans, from Louisbourg to the Rockies. The Seven Years War itself has left us many a laurel. We can afford to hold our heads high." Abbe Arthur Maheux

France stood on the threshold of its greatest age. The nation had become the first military power of Europe. The Sun King, Louis XIV, was France's greatest monarch. Louis XIV certainly thought so and is supposed to have said, "The State! I am the State." He was young, strong, wise and ambitious and determined to construct a mighty realm.

|

|

Louis XIV |

Unfortunately New France did not share fully in the glories of France and her needs were often neglected by a monarch more preoccuppied with affairs in Europe than America. French nobles likewise had little time for Canada but those motivated by money found the fur trade reason enough to be concerned occasionally about what was happening there. A few more selfless souls supported the work of the missionaries working among the Natives. On the whole, however, there was little interest in the colony Voltaire disdainfully dismissed as "several acres of snow."

Despite disinterest in and neglect of the distant colony, the feeble, failing seedling that was Quebec at the time of Champlain's death did take root and flourish. During this proud and prosperous era France commenced creating an empire beyond the Atlantic that resulted from the efforts and the energies of such men as Jacques Cartier, Samuel de Champlain, Count de Frontenac, Bishop Francois Laval, Jean Talon and Rene Robert Cavalier de La Salle.

|

|

The Great Founders of New France |

|

|

The Great Founders of New France |

Its growth was due largely to Jean-Baptiste Colbert, the king's chief minister, who envisioned a revitalized New France that would be an essential link in the mercantilist chain. Mercantilism was an economic system by which a country gained strength and greatness by becoming self-sufficient using colonies to ensure that the mother country had a ready source of raw materials and a market for its finished products. This trading system was closed to all other countries thereby freeing the mother country from dependence on other nations. The system required a strong, centralized, colonial government closely controlled from France.

|

|

Jean-Baptiste Colbert |

Settlement in New France was slow because its chief industries, fishing and fur-trading, did not require a sizeable population but instead flourished with few people. To facilitate the growth of the colony charters were granted to the early companies which required them to colonize New France. They failed to fulfill this task and by 1663 the population of New France was no more than 2,500 souls. Agriculture developed so slowly the colony was unable to feed itself and depended on food for the table from France. Even the supply of fur pelts was reduced to a trickle because the feeble colony was unable to defend itself from the relentlessly ruthless raids of the Iroquois.

Colbert wanted New France to become a "compact colony" that was self-reliant and defensible with a prosperous agricultural foundation and its own basic industries in the St. Lawrence Valley. In a letter to Frontenac in May of 1674 Colbert stated that "you should not make long voyages up the St. Lawrence River, nor even that in the future the colonists should spread out as much as they have done in the past. Strive to crowd them together and to group and settle them in towns and villages and so give them the greater possibilty of protecting themselves wsell." Before his master plan could succeed, New France had to become self-sufficient, something that would not occur until the colony was able to keep its citizens safe from Iroquois incursions. The Iroquois "by the massacre of numbers of French and by the cruelty which they exercise on those who fall into their hands prevented the country from being more populous."Frontenac was to make exceptions to this rule only if it were necessary to take possession of lands in order to protect French commerce and trade from other countries. Otherwise rather than go to the Natives for furs, let them come to you.

Louis XIV responded to the pleadings for protection and resolved "to carry the war to their doors and to exterminate them entirely." To accomplish this pledge 24 companies of regulars were dispatched to Canada during 1665 of which twenty belonged to the Carignan-Salieres. This regiment's rescue operation was intended to provide a breathing space for the colony to establish an economy and a social-political organization. The total number of troops involved exceeded 1200.

As the troops in their broad black hats, grey tunics and mauve stockings marched up the winding road to their barracks on the heights above the St. Lawrence, the bronzed veterans - musketeers, pike-men and grenadiers - brought hope to a despondent Canada. Now for the first time the colony could take the offensive against her enemies. During the summer four companies were sent to the Richelieu River where they constructed a series of forts along the water highway of the Mohawk. Great rejoicing greeted the arrival at Three Rivers of a flotilla of a hundred canoes filled with furs brought by Natives who had successfully run the Iroquois blockade of the Ottawa River.

The first punitive raid on the Mohawak took place in January 1666. Soldiers suffered from frostbite and the unfamiliarity of travelling on snowshoes. Accounts recorded that ears, noses, fingers, hands and knees were frozen as the men, paralyzed by the cold icy blasts and by snowblindness, were dragged by companions to little snow shelters. This less than successful assault was followed by another in September involving a formiddable force of 1200 men. The Mohawk deeming it unwise to make a stand against such a force decided descretion was the better part of valour and simply disappeared into the bush. The French after sacking and burning their abandoned towns returned to Quebec. While no major engagement occurred the Mohawks were impressed with French power and gave serious thought to a negotiated peace. Given pause to ponder they concluded a peace treaty before winter which ensured security for nearly twenty years. Having contributed to the colony's defence, the soldiers then contributed to its growth. When their tour of duty was over many soldiers settled on the banks of the Richelieu River, the one-time warpath into Canada of the mortal enemy of the French colony - the Iroquois.

|

|

Pikeman and Musketeer of the Carignan-Salieres Regiment |

|

|

New France Governmental Structure |

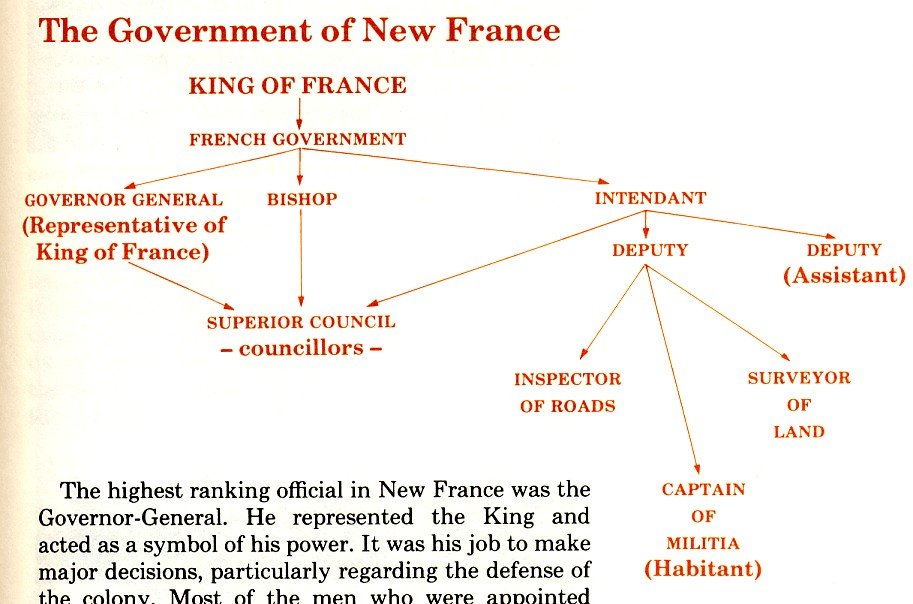

In 1674 New France became a royal colony and was given the same kind of constitution each province had in France. While the British colony of New England had an elected assembly which was deeply involved in governing the colony, New France was always under the direct control of France and completely dependent on it. New France was given a governor appointed by the French king and responsible to him. The governor lived in Quebec, carried out the king's policies and directives and was assisted by associate governors in Montreal and Three Rivers. The governor commanded the military operations and oversaw Indian affairs. In peace time the real power lay in the hands of another important official, the intendant, who was responsible for local administration, justice, police and finance.

The society of New France mirrored 17th century society in France. It was fashioned on authoritarian lines with power concentrated at the top of society - the sovereign. Colonists had no official decision-making powers and were expected simply to obey the authorities. There were no provisions for self-government. The monarch was absolute; land tenure was feudal and commerce was controlled by the merchant-capitalists. These systems were transplanted to North America and adapted to the needs of the new colonial community. The feudal society and its relationships were based on the holding of land. Land in the early 17th century was regarded as the basis of all real wealth. Social status was all-important and it was measured to no small degree by the amount of land a family owned. With feudalism the lord owed duties to the sovereign and military leadership to his tenants. Tenants in turn owed obedience and armed service to him.

The people of New France were drawn from limited areas within France. They came mainly from Normandy, the neighbouring provinces and from Paris. With few exceptions they were northerners and the northern French followed the maxim: "No land without a lord," In New France the power of the state was rarely absent from the settlers' lives and this is the way they wanted it. Where nature responds easily to nurture, government is normally a nuisance, but in a land where life was hard and where every grain of wheat demanded lots of labour, settlers needed all the assistance they could get. Thus it was in New France and later in Canada. For the big jobs like, for example, building railroads, Canadians had to work as one to accomplish their goals. Private initiative was not up to the task. This resulted in a decided difference in attitude toward government in Canada and in the United States.

Commencing a new life in the Canadian wilderness was a daunting prospect and most of the French who came to Canada came because they were sent. Immigration grew out of official policy decisions rather than individual excitement over the lure of the new land. Crossing the Atlantic was a dangerous endeavour. The tumultuous trip could take anywhere from three weeks to more than three months. Conveying passengers was a new concept for which ships were not equipped and crews could not cope with its demands. If headwinds lasted too long food supplies sometimes ran out and scurvy took its toll. As late as the mid-eighteenth century if fewer than ten per cent died en route it was thought to be a good trip. Little wonder few voluntarily set out on the endless sea to take their chances in the wilderness of Canada.

The land-holding system of old France, seigneurialism, was introduced into Canada but under Canadian conditions it had been softened and improved. Under the seigneurial system companies were given large tracts of land (estates) which were then ceded to seigneurs, who were literally lords but were actually squires, gentry, gentlemen or persons of merit. Seigneurs, who lived in a manor house, were granted large landed estates called seigneuries.

|

|

Manor House of the Beauport Seigneury |

Seigneurs in turn were expected to grant smaller, long, narrow farms with river frontage to feudal tenants - ordinary farmers or habitants. The habitants did not have outright ownership of their piece of land since the ultimate owner of all land was the king. Tenants were expected to pay the traditional dues that were paid by the peasants in France, but they were more lightly taxed and enjoyed greater independence than their counterparts in France.

|

|

Habitant Cottage |

In legal documents habitant was used to signify a resident but in common usage it meant anyone below the seigneurial rank who held land in the colony. Habitants were not downtrodden peasants but self-sufficient, self-respecting farmers who were not servile in any way. According to a traveller who visited the colony, the farmers in New France detested being called peasants as their counterparts were called in France. Even the poorest habitant and his wife were called "Monsieur and Madame." The habitants living on the long, narrow farms that ran down to the St. Lawrence and the Richelieu rivers were men and women who had blended their European heritage and the American environment into something unique. They had more freedom than the peasants in France. In fact, royal officials in New France frequently complained that the independent-minded Canadians pleased themselves and paid little attention to the seigneur's directions.

The habitants' lives were centred on their farms which they cultivated with the families' help.

|

|

Habitant Farm |

|

|

Interior of Habitant Farmhouse |

The secret of the habitants' relative freedom and independence was their numbers and their mobility. Few immigrants came from France - one French official said he did not intend to depopulate France to populate New France - and tenants for seigneuries were scarce so seigneurs had to lighten the feudal burdens in order to keep habitants on their estates. The shortage of habitants was made more acute because of the freedom offered by the forest to young men who rather than farm wished to slip away to trade furs despite great efforts to keep them down on the farms. Farming had to be made as attractive as possible and this led to lower taxes, bonuses to farmers with large families and a degree of independence unknown in France.

Estates were held in trust based on the fulfillment of certain obligations one of which was that land should be sublet to settlers brought out by the companies. This critical obligation was often neglected by the companies. For example, the charter of the Company of New France awarded in 1627 required it to bring out 4,000 colonists within 15 years. Little more than lip service was paid to this commitment which was not fulfilled.

|

|

Le Canadien |

Even when land was sublet to settlers there were some who preferred life in the adjoining forest into which a number disappeared. These men became known as coureurs-de-bois, 'runners of the woods woods,' freelancers who engaged in fur trading or hunting and fishing often with a band of Native trappers. They became associates in the blood, terror and toil which became part of their lives. In various degrees the cultures of the European and the Indian had influenced each other from the start. Coureurs-de-bois gloried in their physical prowess, fought in the Native manner, travelled by canoe and snowshoes, wore dearskin and moccasins and slept in bark shelters or bough-covered leantos.

|

|

Coureur-de-Bois |

During the French regime it is estimated that as many as 15,000 individuals took to the woods and the wilds, roving and hunting in the terrifying but exhilarating freedom of the huge, cruel land. Their courage, self-confidence, initiative and love of adventure carried them through incredible hardships. As these roaming woodsmen explored unknown lands and gathered wealth in furs that were so vital to the existence of the colony, they also extended the boundaries of New France. By blazing the first trails throughout the continent they filled out the the map of North America which held two great prizes: rich fur trade and vast hinterland. France was showing every sign of winning them both.

|

|

Coureurs-de-Bois Trading with Natives |

One French officer provided this description of the work of these men who would quickly sell their cargo of pelts, drink and gamble away their profits and vanish down the rivers and into the woods to repeat the whole process. "The pedlers call'd Coureurs de Bois export from hence every year several canows full of Merchandise which they dispose of among all the Nations of the Continent by way of exchange for Beaver-Skins. I saw twenty-five or thirty of these Canows return with heavy Cargoes; each Canow was managed by two or three men and carry'd twenty hundred weight, forty packs of Beaver Skins which are worth a hundred Crowns apiece. These canows have been a year or 18 months out."

In the 17th century the name coureur-de-bois meant anyone who voyaged into the wilderness to trade for furs. Later in the life of the colony attempts were made to place restrictions on the number of these men by licencing them and any coureur-de-bois who were unlicensed became illegal traders frowned upon by the state and chastised by the Church for their wild ways. Their name became synonymous with outlaw. Their flight into the forests was considered to be a drain on New France, a waste of badly-needed workers to farm, feed and help build the colony. However, whether they were licensed or not their energy, daring and knowledge of the Natives resulted in the success of the France's far-flung fur trade, a trade increasingly being encroached upon by the English. In spite of being considered illegal fur traders many believed they held the fate of New France in their hands.

Early in the 18th century the term voyageur was used to describe wage-earning canoe-men who transported trade goods and supplies to the western posts. Few human beings on earth could match the voyageur for strength or endurance. In every sense of the word they were supermen. "Short, thick, tireless men who resembled fiends in the oppressive heat, their shirts off, their skins like heated copper and their long black hair loose with their wild, black eyes glowing like coals." Few were more than five feet six inches tall because no one larger could fit easily into the canoe. They had tremendous shoulders and arms for on the roughest portages they never carried less than one hundred and eighty pounds, Some carried twice that and at least one of them is credited with carrying five hundred-ninety packages of trade goods on his back as he trotted through the forest tangle. They needed 9000 calories a day to maintain their killing pace and their staple food was a mush made of dried beans, salt port and sea biscuit. One might have expected them to puff and pant along the path but they sang - lustily.

|

|

Voyageurs |

|

|

Voyageurs |

|

|

Voyageurs |

|

|

Voyageurs at Dawn |

By 1663 France out of a population of 16 million (double the size of England which sent out 40 thousand settlers to New England) had provided Canada with only 2500 settlers. Most of these were confined to three small settlements: Quebec, Montreal and Three Rivers. King Louis sought to save his tiny settlements overseas by bringing them under his direct control. Louis took the colony in hand by winding up the Company of New France and replacing it the next year with the Company of the West that had privileged rights of trade in all New France. When Louis began to rule, the population of Canada was similar to that of a large French village and stretched along three hundred miles of the St. Lawrence. There were three fortified settlements; Quebec, Three Rivers and Montreal. Danger was ever present in the outlying settlements where Iroquois warriors swooped down in birch-bark canoes, burning log cabins and scalping missionaries. While the settlement was very poor it was strong in religious zeal.

|

|

Louis XIV (From a painting in the Versailles Gallery) |

On June 30, 1665 two ships came to anchor below the Rock in the Basin of Quebec with the royal standard of France flying from the mast of the larger vessel. From the bastion of St. Louis, cannon thundered out a salute. The Lieutenant General of all the king's possessions in North America, the Marquis de Tracy, along with the Intendant Jean Talon had landed with pomp and pageantry at Quebec.

|

|

Seigneur de Tracy |

Louis XIV's chief minister, Jean Baptiste Colbert, established the foundations for a permanent colonial bureaucracy responsible to the king. Three officials comprised the colony's leaders. The government was comprised of two senior officials: the governor who was the chief administrative officer and head of military and Indian affairs. The second senior official was the intendant who dealt chiefly with economic, financial and judicial matters. In the absence of any assembly or elected municipal body the government was essentially a benevolent dictatorship. The third member of the triumvirate was the bishop who was responsible for the moral welfare of the community.

|

|

Jean Baptiste Colbert |

Jean Talon became Colbert's chosen instrument for remaking New France and Talon carried out to the full the wishes of his superior. As he sailed up the St. Lawrence he was struck byt the beauty and immensity of the new land and on landing set to work to realize the vision of greatness it motivated. Talon was totally committed with his task as intendant and for seven years Canada preoccupied his every moment. Talon had a clear, orderly mind and a broad outlook on the fascinating problem of founding a great kingdom. He was not reluctant to explore new and alternative ways of dealing with problems and the directing energy to ensure his plans were implemented.

|

|

Jean Talon |

In the spring of 1666 Talon carried out a census which revealled there were 3215 settlers in Canada of whom 2034 were males. In the whole country there were 4 lawyers, 4 surgeons, 20 shoemakers, 11 bakers and 7 butchers. The spiritual needs of the colony were cared for by one hundred persons: 54 clergy and 46 nuns in various monastic orders whose parish included half a continent.

Louis XIV who gave Talon his commission recommended that he take steps to protect against the Iroquois. Peace was precarious with the "irreconcilable enemies of the Colony whose unexpected forays always kept the colony in check and prevented it being more peopled that it is at present." This necessitated compact settlements for defence, the use of waterways for transport and as a source of food. These and the gregarious nature of the people all combined to give the French-Canadian village its particular form. Land holdings were laid out in long, narrow strips reaching back from the water and this gave each settler access to the forest, to fertile valley land and to the resources of the water. Houses were set close together along the river and a single road connected them to the church. The banks of the river resembled a continuous village.

Initially, Talon's chief duty was to build a population. In order to do this marriage became a matter of duty. Boatloads of potential brides known as les filles de roi, (the daughters of the king), were sent out from France to provide brides for veterans of the Carignan-Salieres and other bachelors in the colony. On the arrival of the women bachelors were given fifteen days to conduct courtships and seal partnerships. Early marriages and large families became a tradition in New France and by the end of the century the population had increased to seven thousand.

|

|

Les Filles de roi |

|

|

Talon Visiting with Habitants) |

Talon never lacked energy and his drive was all-pervading. He had forest and mineral surveys taken, imported French horses and other farm animals as well as suitable strains of European grains. He found wealth in the forest whose riches included ashes from burnt trees used to make valuable potash. Acorns were planted to ensure young oaks along the banks of the rivers. He fostered the growing of hemp for rope and the making of pitch and tar. The area of land under cultivation doubled and new industries were launched. He encouraged small industries that included lumbering, tanning, flour milling, salting of fish and the extraction of oil from porpoises and seals in the lower St. Lawrence.

Talon was the father of Canadian ship-building and shortly after his arrival three merchant ships were built on the sand near Talon's palace a short way up the St. Charles River.

|

|

Talon at the first shipyard in New France |

|

|

Talon Inspecting Ship-Building At Quebec |

|

|

Quebec at the time of Jean Talon |

Despite being instructed by Colbert to ensure he did not waste money and manpower in pursuit of furs and exploration, Talon became infatuated with exploration. Eager to extend the name and the fame of His Majesty to distant locations and to claim new lands for his king, Talon sent out French explorers. These included Louis Jolliet, a Quebec trader and navigator who was to the first European to see the Mississippi of which the French had heard a great deal from the Natives. Jolliet and Father Jacques Marquette, a Jesuit missionary, opened the vast interior of North America by discovering the links that connected the rivers and portages of the St. Lawrence-Great Lakes waterways to that of the Mississippi River. The French empire that soon stretched from the mouth of the St. Lawrence to the mouth of the Mississippi hemmed in the British settlements along the Atlantic seaboard. This enabled the French to cut off the English advances to the west and to monopolize trade in the heart of the continent. .

|

|

Explorations of Marquette, Joliet and La Salle |

As more and more Canadian adventurers were fanning out across the continent uncovering the secrets of the west, Talon in letters to Colbert promised ever greater growth for the colony. "Nothing," he wrote,"can prevent us from carrying the name and arms of His Majesty as far as Florida." Greatly perturbed at the prospect Colbert scrawled a single word across the letter "Wait." Then he issued this warning. "Restrict yourselves to an extent of territory which the colony can maintain rather than embrace so much land a part of it must be abandoned." He feared further exploration was spreading the colony's resources too thinly and would involve entangling France in intertribal conflicts with the Natives and perhaps even war with the English. The wilderness, the age old-old siren, had seduced Talon and turned him into an empire builder, a coureur-de-bois in faith if not in fact. When Talon was recalled to France for good in November 1672 for failing to follow orders New France lost a dedicated and devoted servant.

In the annals of New France there is no more prominent figure than Francois de Laval, the bishop. Under the influence of this most powerful prelate in Canadian history, the foundations were laid for a Canadian clergy. The seminary Laval established at Quebec became the University of Laval in 1852.

|

|

Francois Laval, Bishop of New France (From a painting in Laval University) |

Champlain had told the Hurons through an interpreter that if they wished to preserve and strengthen the friendship they had with the French "they must receive our faith and worship the God that we worship." It would, said Champlain, "seal the Franco-Huron alliance."

The Canadian church originated from a mission, the first ministers of which were members of religious orders whose chosen task was the religious conversion of the Natives. While their headquarters was at Quebec or Montreal their true field of action was the wilderness for it was here they found and brought faith to the Natives. Because priests were preoccupied more with missionary work among the Aboriginals than with the settlers, the creation of parishes to serve the people was delayed.

As the 17th century drew to a close the French in America were filled with a sense of magnificent accomplishment. They could contemplate a colony stretching along the St. Lawrence for a couple of hundred miles as well as other smaller settlements in Acadia, Cape Breton, Isle de St. Jean and Terre-Neuve. In addition French explorers had penetrated into the distant recesses of the continent, writing as they did so a chapter in exploration that ranks with the greatest. The French colony produced a a long succession of great men. Some were extremely brave, some were wise and far-seeing, all were romantic and adventurous. Great figures of New France "that emerged into the white light of historical importance" began with Cartier and Champlain and included La Salle, Talon, Frontenac and Laval. They found in Canada the chances and the challenges to match their talents and characteristics and they used these to open a vast new continent and create a great new country - Canada.

Built over the course of a century and a half, the French empire in North America suddenly collapsed between 1758 and 1760. While the French had begun the Seven Years' War on this continent with a string of victories, Britain, urged on and assisted by the 13 Colonies, embarked on an all-out effort to crush France's power in Canada. In the summer of 1758 aided by one quarter of the formiddable British navy some 42,000 British and colonial troops poised for an attack on New France. For the first time the British could aim not simply at territorial gains but at total victory. In an all-out test of strength, New France had little chance against the English colonies. Her vast imperial ambitions in the west were pursued with such scanty means that they could not possibly prevail against a serious challenge. Lack of immigration from France offered no prospect of settlement in the great sspaces of the west.

Canada was under attack by two major armies of invasion. One made its way up the heavily defended corridor leading north via Lake Champlain to Montreal. The other made a seaborne assault by way of the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Earlier this latter force having carried out a costly but successful amphibious assault on Louisbourg, now made its way up the St. Lawrence River to lay siege to the hitherto impregnable Quebec Citadel. The decisive engagement on the Plains of Abraham delivered Quebec to the English. Widely known today because of its dramatic qualities, the battle was an important episode in a much larger campaign. With a little bit of luck historians suggest the French might well have won it but even if they had, the ultimate result would have been the same since Britain was determined to destroy France as a force in North America and prepared to pay the cost in money and men to do so.

Three armies now pressed down upon the colony from the west and the south as well as the east and in the summer of 1760 all bore down on the last French stronghold of Montreal. With its fate more or less sealed two years earlier, Canada finally capitulated on the 9th of September when the British military under the command of Brigadier James Murray took over administration of the colony. Once the decision had been made to keep Canada the government pondered what to do with this foreign colony in a far off land? As one official put it, "Are we not the only people on earth except Spain that ever thought of establishing a Colony ten times more extensive than our own country and yet imagine that when it comes to maturity it will still depend on us?"

Civil rule was not inaugurated in Canada until August 1764. The French had led to expect a reign of terror but instead all three military governors did their best to make life as nearly normal as circumstances permitted. The peace treaty had guaranteed to the French Canadians the exercise of their religions and the maintenance of their institutions - the French language and laws.

What were the consequences of the conquest? Generations of Canadians - English-speaking and French-speaking - have tended to view this event as an important focal point in their country's history. Some historians suggest that this defeat lies at the root of Quebec nationalism. The conquest did have far-reaching effects for Canada. Without it there would never have been an English-speaking Canada nor a two-language federal state.

Was French Canada humiliated by the Conquest and did it enter a period of social disarray? This did not appear to be the way it happened to most contemporaries of th 1760s. Then it was clear that England had beaten France in a war and had taken Canada as its prize. French Canadians had no need to feel like a defeated and humbled people and there is litte indication that they did in the following decades. There was apprehension about language and religion but understanding and supportive governors and the lenient legislation of the British government soon disabused them of any concerns in this regard they might have had.

|

|

General James Murray |

"Some day Canadians of both tongues will have the features of James Murray cast in bronze and set up as a symbol of the good relations which have existed amongst Canadians of every stock."

Abbe Arthur Maheux [*]

|

|

Carleton, Sir Guy |

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 and the Quebec Act passed in 1774 were passed with good intent for French Canadians. In approving the Quebec Act the British government heeded the advice of James Murray, Quebec's first English governor and Sir Guy Carleton his successor. It confirmed to the Canadians the free used of their tongue, their customs and their Roman Catholic religion. It granted them most of the old French civil laws including the seigneurial tenure of land. It ensured the rights of the clergy to collect tithes and it offered the people an oath of allegiance that contained no insulting religious clause. The matter of an elected assembly was set aside for the majority of the Canadians had no knowledge of democracy or the principles on which it worked. They were ruled by a king's deputy and his little court at Quebec and as long as it was light they preferred it. This was replaced by a governor and council appointed by the British crown. The act was a matter of simple justice to Canadians.

According to Jean Charest, Premier of Quebec,

"Canadians made a decision very early in their history a choice that over time has come to define the very essence of who we are. Our ancestors decided right from the start, to build a country based on the right to speak a different language, to pray in a different way, to apply a different legal system based on the French Civil Code, to belong to a different culture and to enable that culture to flourish. The Quebec Act of 1774, passed into law more than 200 years ago, almost a hundred years before Confederation, is in this respect the most fundamental document in Canadian history. It is the foundation upon which the Canadian partnership was originally built. Its spirit defined this country from its very inception. It represents one of the most enlightened decisions ever made for Canada. Canadians should reflect upon this choice that was made so early in our history. We should reflect on how it defines us, how the French language and culture and the presence in the federation of a French-speaking province has allowed Canadians as a whole to extend their influence and play a greater role in the world community." French fellow citizens brought with them the proudest and most distinguished tradition of Europe. It has never been forgotten and it is this background of two proud cultures utterly different that gives to modern Canada its own especial character.

Some thirty years after the conquest the Imperial parliament passed the Constitutional Act of 1791. Known initially as the Quebec Government Bill, this 31st Act of the King was written by William Windham Grenville. Prime Minister William Pitt had little time for Canada and he left the legislation largely to the industrious but unimaginative Grenville who was Secretary of State for the Home Office and Pitt's favourite cousin. The prime minister was preoccupied with the revolution in France raging across the English Channel and with the periodic insanity¨ of his sovereign George III with whom Pitt was not always on the best of terms. George III was jealous of anyone with ability and quick to perceive and resist any sign of independence in his ministers. He was less than enthusiastic about the Quebec Bill.

The CONSTITUTIONAL ACT 1791 GEORGE III XXXI Year of Reign

An Act for making more effectual Provision for the Government of the province of Quebec, in North America; and to make further Provision for the Government of the said Province.

"II. And whereas His Majesty has been pleased to signify, by His Message to both Houses of Parliament, His Royal Intention to divide His Province of Quebec into Two separate Provinces, to be called The Province of Upper Canada, and The Province of Lower Canada; be it enacted by the Authority aforesaid,

That there shall be within each of the said Provinces respectively a Legislative Council and an Assembly, to be severally composed and constituted in the Manner herein-after described; and that in each of the said Provinces respectively His Majesty, His Heirs or Successors, shall have Power, during the Continuance of this Act, by and with the Advice and Consent of the Legislative Council and Assembly of such Provinces respectively, to make Laws for the Peace, Welfare, and good Government thereof, such Laws not being repugnant to this Act."

[*] French Canada & Britain by Abbe Arthur Maheux

Copyright © 2013 Website Administrator