Foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

JACQUES CARTIER

History is the actual drama of actual men who are no more.

When Two Worlds Met

"Man's urge has always been westward, face into the winds that ring the dim verge of the known world. The history of modern North America is the record of this westward urge."

|

|

Sketch by Dan Lailler of an Early Portrait of Cartier |

|

|

Portrait of Jacques Cartier |

Eyes of Discovery

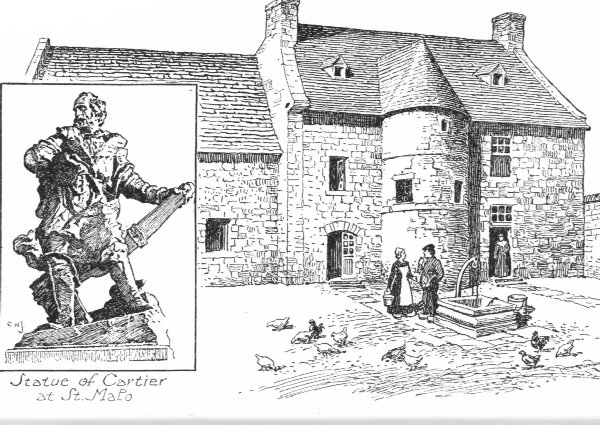

Jacques Cartier, a Breton of the stout seafaring kind, was born in St. Malo in 1491. The ancient town of St. Malo was a wealthy port in Brittany in northwestern France. The rugged port with its crowded peninsular town jutted like a buttress into the sea to form a harbour. Strange and grim of aspect it breathed fire from its walls and battlements of ragged stone, a stronghold of privateers and the home of a race whose intractable and defiant independence neither time nor change has subdued. For centuries it was a nursery of hardy mariners and among the earliest and most eminent on its list stands the name of Jacques Cartier. The place had a reputation for hardy seaman and Cartier was then its boast and has been ever since. His portrait hangs in the town-hall of St. Malo - bold, keen features bespeaking a spirit not apt to quail before the wrath of man or of the elements.

At forty-three years of age, Cartier was a stocky man with a sharply etched profile. His calm, steady, thoughtful eyes under a high, wide brow held a hint of power. His face, slightly hawk-billed with a beard that bristled defiantly, was normally calm in contemplation of the sea, but easily roused to rage and violent action. Some contemporary records call him a corsair, meaning he roved the seas depoiling the enemies of France. Cartier was a skilled mariner, a full-fledged, fearless navigator who was held in high regard by seafaring men. He may have voyaged to Brazil. When he married in 1519 he had risen high enough in his profession to be called a master pilot. He was known as a capable and couragous captain who was fair in all his dealings. He was fully knowledgeable of everything concerning ship handling, especially making sail. Considering he made three voyages of discovery in dangerous and hitherto unknown waters without losing a ship and considering he entered and departed from some fifty undiscovered harbours without serious mishap, it can be assumed he knew his craft as captain well.

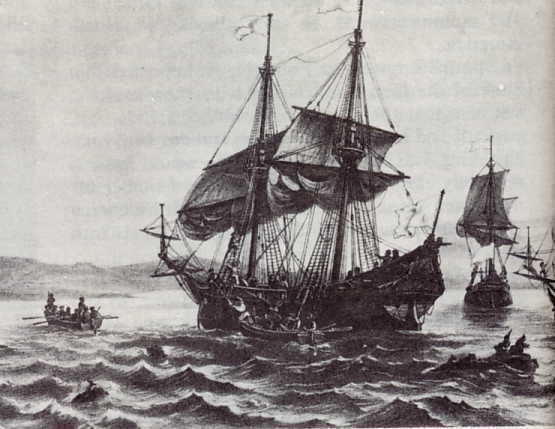

Fish and fur had first attracked Europeans to Canada. At the end of the 15th century, Cabot exploring off the waters of Cape Breton Island reported such a quantity of cod that shoals sometimes "stayed his ships." Cartier's crew signed on although they could have made mre fishing and trading on Newfoundland's coast. Preserved at St. Malo is a list of those who finally signed the ships' papers made out in Cartier's own hand. Cartier oversaw the equipping of his two vessels of sixty tons each and when his men had been piped aboard, they numbered sixty-one souls. When his vessels righted with the flood (tide in) and their booms creaked to the vigorous pull of their crews, the gazing idlers along the shore waved their farewells to St. Malo's maritime hero.

On April 20, 1534 the two little sailing vessels hardly more than yachts departed from St. Malo, the old harbour steeped in the seafaring tradition, Their commander's stocky legs were planted firmly on the upper deck, his dark eyes fixed straight ahead on the sea. Even in the summer anything could happen in the North Atlantic. Westerly gales hurled crested seas against the little barks bouncing them about and often forcing them to lay-to for days. Easterly gales drenched sailors with chilling rain and fierce northerlies shredded sails. Sailors had to fight for their lives sinc every harbour they entered was risk to life and limb. Subjerged just below the surface, rocks capable of ripping the guts out of a ship were difficult to see in the dark, green opaque waters. Despite seafaring competence and caution countless ships dropped to the depths in these northern waters, their crews lost forever in the cold deep of the dark sea.

Aware that 'America' and 'Americans' had already been discovered, Cartier sailed to seek riches and to solve the enigma of the silent continent far to the west. His actual commission has never been found, but an order from King Francis I in March stated the objective of the voyage was "to discover certain islands and lands where it is said a great quantity of gold and other precious things are to be found." A second objective was to find the route to Asia. To the European imagination of the 16th century, the names India, Java and Cathay had about them the glitter and gleam of jewels and gold, the savour of spices, the fragrance of perfumes and the texture of silk. The dream of finding fortunes motivated the minds of Europeans who ventured westward across the wide, empty ocean. Among those dreamers was Jacques Cartier.His first voyage was a mere reconnaissance but the spirit of discovery was awakened. Mingled with the views of interest, ambition and wealth was another motive scarcely less potent - winning to the fold of the church the Natives of the new world.

|

|

Jaques Cartier |

|

|

Cartier's Manor House at Limoilou Near St. Malo |

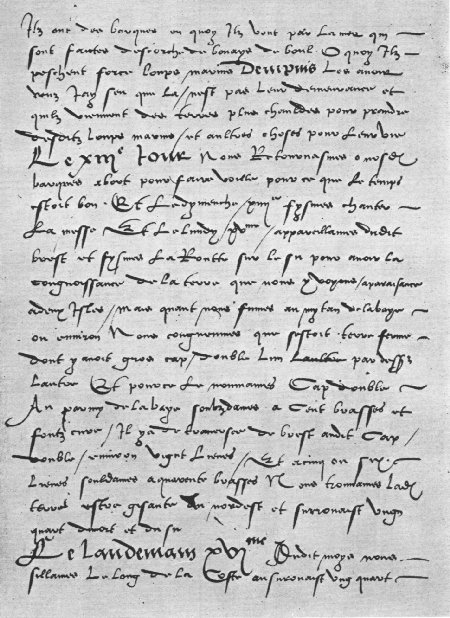

Cartier's records of the three voyages he eventually took are rich in detail about almost every aspect of the eastern North American environment and the people who inhabited it.

|

|

Page from Cartier's Diary |

Favoured by "good weather," Cartier crossed the Atlantic in 20 days and began to explore along the unknown coast of Labrador. His square-rigged vessel was not easily manoeuvrable and with an offshore wind, the intrepid discoverer, if he wished to learn anything at all about this new land, had to sail close to shore, a risky endeavour especially near the fog-bound shores of Newfoundland. While some distance off the grim Newfoundland coast the two vessels hove to. From the decks of their low-riding craft, neither more than 60 tons burden whose gunwales barely cleared the rolling waves, Cartier and his sixty bearded crewmen gazed in amazement at the sight before them. The new world was beginning to reveal its wonders - birds, sea birds by the thousands, swarming over and around one lonely rocky island in such numbers that "all the ships of France might load a cargo of them without once perceiving that any had been removed." The wonders of the new world included "wild and savage folk who covered themselves with certain tan colours" These Natives were the now extinct Beothuks.

The weather like the days was dark and gloomy. Through the mist and fog on the face of the water the formiddable coast came into view. "The land should not be called New Land, being composed of stones and horrible rugged rocks…. I did not see one cartload of earth and yet I landed in many places… there is nothing but moss and short, stunted shrub. I am rather inclined to believe that this is the land God gave to Cain." Thus wrote Jacques Cartier on his first image of Canada. After exploring along the coast of Newfoundland Cartier rounded the northern tip, passed through the Strait of Belle Isle and sailed south-west along the shore into the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

After crossing the gulf the Frenchmen came upon an island which Cartier named St.Jean (Prince Edward Island). Turning his ships northwest, he followed the outline of the coast and beheld "the fairest land that may possibly be seen full of goodly meadows and trees." They had reached the shore of what is now New Brunswick. Because the heat was so intense in the bay in which they came to rest, Cartier named it Chaleur and the Bay of Chaleur it has been ever since.

When the explorers finally left their ships to go ashore, they recorded that many eyes were watching them. Suddenly as if by magic lithe, lean, rugged, fearsome-looking men, appeared, their faces "hideously coloured with red and white ocre," After signalling that they wished to trade, they launched their canoes and with amazing speed approached the apprehensive aliens. Alarmed by the outlook Cartier and his men turned their boats about and rowed back towards the safety of their ships. The Natives paddled furiously and with a speed that astonished the Frenchmen soon urrounded these strangely garbed newcomers. The Aboriginals, making a great noise and gesticulating wildly, signalled a willingness to trade, "setting up a clamour and making frequent signs and holding up to us some furs on sticks."

|

|

Cartier & Anxious Aboriginals Offering to Trade |

But Cartier "did not care to trust their signs." Fearing trouble he raised his arm in a pre-arranged signal and salvos were fired from two little cannons. their smoke and thunder scattering the painted people in all directions. They had not gone far, however, before curiosity overcame their caution. The turned about and once again approached the Frenchmen. This time Cartier ordered his men to raise their muskets and fire a volley into the air. The sharp sound of the "fire lances" - projectiles packed with "sulfur, cannon powder, powdered lead, broken glass and mercury" - shattered the air about their ears, shaking both their courage and their curiosity as they fled from the terrifying blast.

Cartier noted in his diary that they "would no more follow us." They did, however, for the following morning they reappeared with an obvious desire to trade. Cartier provided the first detailed description of the ceremonials surrounding trade when they returned on July 7th, "making signs to us that they had come to barter." Cartier had brought well-chosen trade goods: "knives, hatchets [See Below *] and other iron goods and a red cap for their chief.". Before long the Natives were eagerly trading beautiful furs for tawdry trinkets. The first day of the exchange was brief. In exchange for furs including those they were wearing, Cartier gave them "knives, glass beads, combs and other trinkets of small value."

The Natives on the shores of the Bay of Chaleur were probably Micmacs. Those whom Cartier met further north in the Gaspe Basin were a migrant tribe of the Iroquois who had come from a distant region near Quebec to fish and take seals. Later Cartier encountered Iroquoians cultivating land and controlling the country around present-day Montreal. Cartier began to realize that these North American people were not all alike. They spoke different languages, practised contrasting lifestyles and warred against each other.

|

|

Cartier at Perce Rock, Gaspe 1534 |

"There are, it may be said, many kinds of voices in the world and none of them is without signification. Therefore, if I know not the meaning of the voice, I shall be unto him that speaketh, a barbarian. And he that speaketh shall be a barbarian to me. 1st Corinthians 14, 10-11.

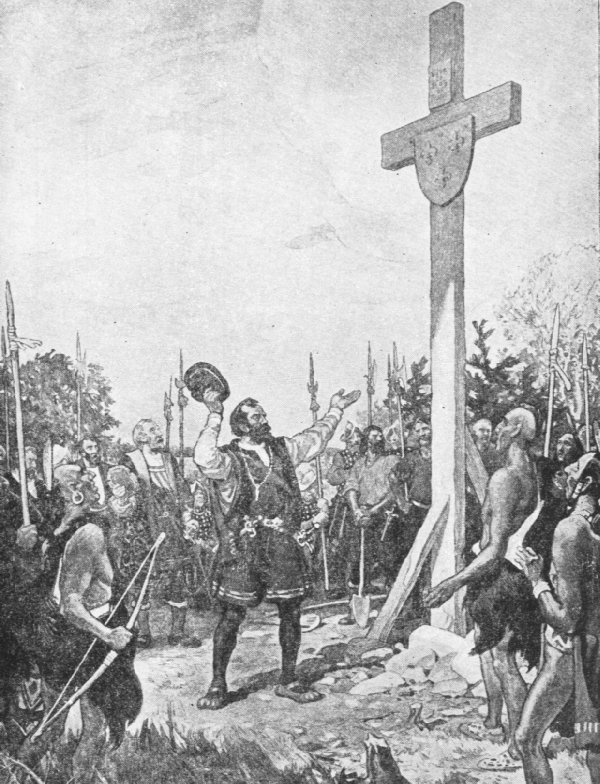

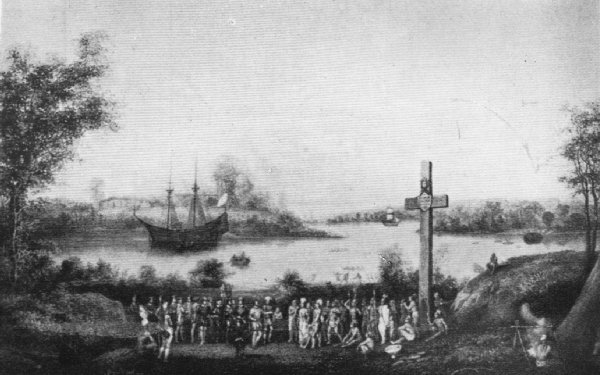

The next day Cartier turned north again and came to another deep bay which he hoped would lead to the illusive Cathay. From the abundant timber at hand he had constructed on the point at the entrance to the harbour a cross thirty feet high. Under the cross bar "we fixed a shield with three fleurs-de-lys in relief and above it a wooden board engraved in large Gothic characters where was written Vive Le Roy De France." Here on Friday July 24th 1534 at Penouille Point on land he named Gaspe, Cartier claimed for France a sovereignty which endured for more than two hundred years. Great ceremony attended the event and the onlooking Indians, who had come from Stadacona to fish, realized instinctively that Cartier was claiming this land.

|

|

Cartier Erecting Cross at Gaspe |

|

|

Possession In The Name of Francois I |

After the French had withdrawn to their ships, Donnacona, the local chief dressed in an old black, bear-skin, arrived in a canoe with his three sons and his brother. The chief pointed shoreward to the cross and the land all about and with hand signs and a long harangue attempted to make it clearly understood that the country belonged to him and his people. Before long, however, he was pacified by gifts and other goodies including food and drink. Cartier resolved to carry some natives back to France and requested the chief's consent to take with him two of the chief's sons, Domagaya and Taignoagny. After receiving shirts, red caps and other clothing, the sons readily agreed to make the trip. The next day the ships weighed anchor and their departure was accompanied by boatloads of shouting, waving Natives. Despite being tossed about by tempests, the Frenchmen finally found fair weather "and upon the 5th of September in the said year we came to the port of St. Malo whence we departed." Apart from the two Native youths who created quite a sensation at the Royal Court Cartier had little to show the king for the voyage.

|

|

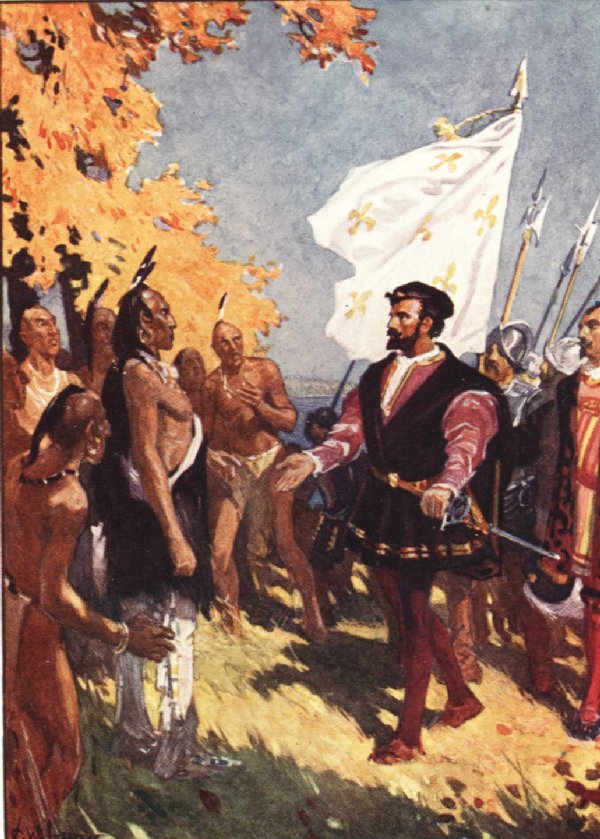

Cartier and Natives |

On the 19th of May 1535 Cartier set forth on his second and most important expedition to the new world. His objective: to find the Great Lakes and the elusive route to China. By the middle of May the three ships, the Grand Hermine 120 tons, the Petite Hermine 60 tons and a small vessel of 40 tons known as Emerillon, were manned and provisioned awaiting only a fair wind to sail. The company numbered in all one 120 persons. Shortly after the three ships had set sail, fierce winds separated them and they were not reunited until they reached Newfoundland eleven weeks later. Included among the crew were the two Aboriginal boys whom Cartier had spent two months quizzing in Paris and St. Malo. With their help Cartier eventually "found the way to the mouth of the great river of Hochelega and the route toward Canada."

In the sparkling sunshine on the 1st of September, Cartier reached the mouth of the Saguenay and anchored probably in the little bay near Orleons and Tadoussac "where the province and territory of Canada begins." The name Canada then applied only to what is now Quebec. Cartier was guided by the two Indian youths who had learned French and during the voyage had transfixed the crew with stories of a fabulous, miraculous, mysterious Kingdon of Saguenay that was rich in silver, gold and precious stones and was located somewhere to the north. Cartier swallowed their stories hook line and sinker. Eagerly anticipating visiting this treasure trove. he followed the boys' direction,nd took "the route to Canada" and sailed up the great St. Lawrence River which he always called La Grande Riviere.

|

|

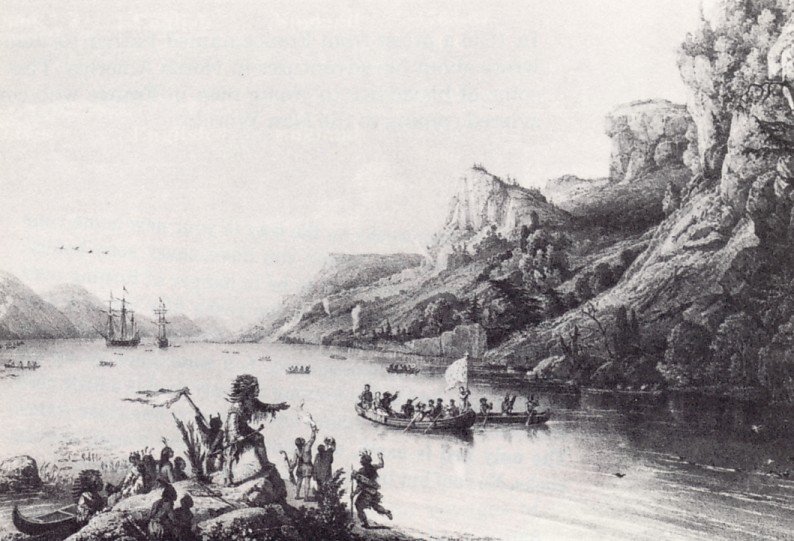

1541: Cartier on the St. Lawrence |

Its size and stately appearance impressed him greatly. The mighty river, a majestic portal, stretching inland almost four thousand kilometres, was lost in the hazy distance of the remote and changing horizon. It was the one great river which led from the eastern shore into the heart of the continent. The St. Lawrence shouted its uniqueness to adventurers, the vast riches of whole west its dominion. To the free-spirited and the visionary it offered a passage to the central mysteries of the continent. It meant movement, a ceaseless procession west and east of river craft - canoes, bateaux, timber rafts and steamboats - following each other into history. This destined pathway of North American trade streams like an obsession through the whole of Canadian history.

In a letter of dedication to his sovereign, Francis I, Cartier wrote, "The great river which flows through and waters the midst of these lands of yours, which is without comparison the largest river that is known to have ever been seen." The forest along its shores were ablaze in golden ash and red maples. Cartier's first impression of this new continent was its vastness and stillness. It was once suggested that "To enter Canada is a matter of beinging silently swallowed by an alien continent." At no time could this have been truer than on that day when Cartier cast his eyes about him at the tranquil land "awaiting the arrival of man to waken it to fruitfulness." The forests were tall, impenetrable, interminable and inscrutable, the only sounds issuing from the daunting denseness, the occasional splash of leaping fish and distant cawing of a crow from the treetops. When Cartier reached the site of Tadoussac at the mouth of a deep river flowing north which the natives called Saguenay, he sailed a short distance up but turned about when the boys said they "wanted home." They told him there was another, better route further west.(the Ottawa River)

|

|

Arrival of Jacques Cartier at Quebec 1535 |

Cartier continued up the St. Lawrence and on the 8th he reached heart of the country that had given the land its name, Cannata ('village' or 'settlement') in the Iroquois-Huron language. The St. Lawrence narrowed as it flowed between a bold promontory and a broad, beautiful island on which the Native village of Stadacona stood in the shadow of the great Rock of Quebec. The land around it was called Canada.. "On the morrow the lord of Canada named Donnacona came to our ships accompanied by many Indians in twelve canoes." On deck the two men from vastly different worlds attempted to converse. Taignoagny and Domagaya, whom Donnacona never expected to see again, told their father what they had seen in France and that they had been well treated. At this Donnacona expressed much pleasure.

Later Cartier visited with Chief Donnacona at his village Stadacona, now Quebec City (from the Huron Kebec 'the narrowing place.') lying at a point where the mighty river St. Lawrance narrows to the breadth of a mile. Cartier recorded "this marks the beginning of the land and province of Canada."

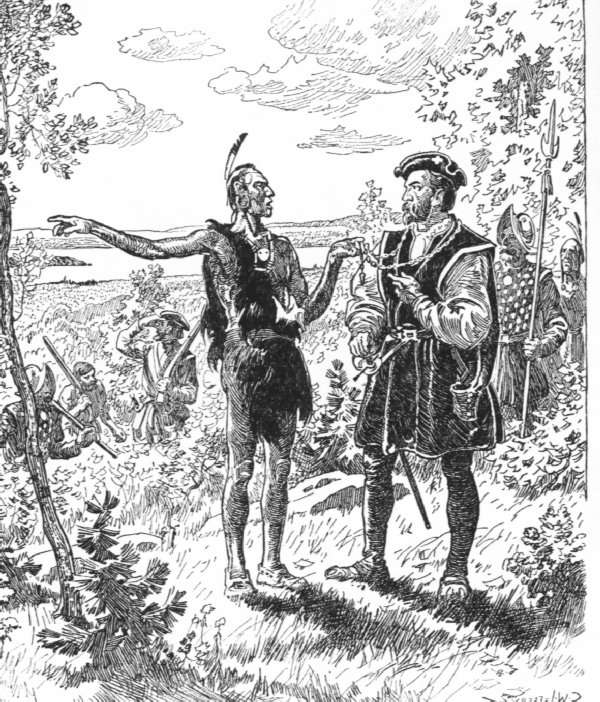

Cartier was eager to proceed to Hochelega, but he noticed that his two young guides had become somewhat distant. Donnacona too was reserved and urged Cartier to stay at Stadacona, declaring the river of little importance and the journey not worth making. Cartier replied he had been commanded by his king to go as far as he could go and that after seeing Hocheleg he would return. The next day the Natives tried again to dissuade Cartier from continuing his journey, but finding persuasion and oratory of no avail, they summoned the supernatural to frighten the French into remaining at Stadacona. Three Natives were carefully made up to strike terror into Cartier and his companions. They were "wrapped up in dog skins, white and black with horns on their heads more than a yard long."

Anxious to protect their position as middlemen, Donnacona was reluctant to have Cartier continue up the river to Hochelega. The Natives of Stadacona did not want those of Hochelega to have the wondrous metal goods the French had brought or if they were ever to have them, to receive them only by trading for them with the Natives of Stadacona. Competitive commerce was by no means unknown to these men of the Stone Age. The old chief wanted to maintain a monopoly on trade with the French and their fortunes. Once during his conversation with Cartier, "all his people at once in a loud voice cast out three great cries together in full voice, a sound horrible to hear." It was the Indian war whoop which in days to come would curdle the blood of many in New France. Despite being told the French would freeze to death of they proceeded west, Cartier insisted that he must go. Donnacona finally gave in but refused to provide guides. Cartier and a company of fifty in all set sail for Hochelega on the 19th of September in the Emerillon.

|

|

1541: Donnacona & Cartier |

|

|

1541: Cartier At Hochelaga |

The journey west to Hochelega (now Montreal) took thirteen days. The glowing fall colours delighted the French who recorded they observed "the finest trees in the world" that included oaks, elms, pines, cedars and birches. Some 80 kilometres from Montreal, Cartier had to leave his galleon, Emerillon, at Lake St. Peter because the rapids in the St.Lawrence which Cartier in jest named La Chine (China) prevented his journey by ship further up the river. He left it well guarded and continued in longboats. Finally they reached open fields with a great mountain looming up behind. This highest point along that part of the St. Lawrence was called by the Natives, Hochelega, a typical Iroquois village n the midst of cultivated fields of maize or Indian corn. (Today the site is occupied by McGill University.)

The palisaded town of fifty longhouses, which were about forty-six metres in length and fourteen metres in width, each accommodated several families. The well-fortified place was as constructed by the Iroquois - "compassed round about with timber with a triple row of tree trunks, one within another and framed like sharp spikes." There were galleries at intervals on which were piled stones for use against attacking enemies. This was not the sought after city of the East. In the heart of the town was a public square wherein Cartier was welcomed by the chieftain borne upon the shoulders of his men. By Cartier's own estimate they were greeted by a thousands of excited people demonstrating wildly with wonder and delight at these hairy, oddly clad strangers. "They showed their joy, danced and performed various antics." The strangers were beset by a throng of women and children who touched their beards, felt their faces and gazed in wonder at their strange dress and weapons. Cartier offered up a prayer and made the sign of the cross . It was all wizardry to the astonished Natives who better understood the French when Cartier amid a flourish of trumpets began to hand out hatchets and knives to the dusky applicants.

On the day of their arrival Cartier and his men climbed the mountain and at the top beheld in all its autumn splendour the countryside for miles around. The view was so impressive a panorama that Cartier called the mountain, Mount Royal, which gave its name to Montreal. Mountains could be seen in all directions. To the north lay the Laurentians and the Green Mountains. The Adirondacks were to the south. Cartier described the wide Laurentian landscape that opened before him. "On reaching the summit we had a view of the land for more than thiry leagues round about. Towards the north there is a range of mountains running east and west. And another range to the south.

Between these ranges there lay a great plain, the fairest land it was possible to see, being arable, level and flat. And in the midst of this flat region flowed a mighty river "grand, large et spacieux." extending beyond the spot where they had left their longboats. "There is the most violent rapid it is possible to see which we were unable to pass. As far as the eye can see, one sees the river, grand, broad and extensive which came from the southwest and flowed near three fine conical mountains which we estimated to be some fifteen leagues away." He scanned the misty distance in which the St.Lawrence on the one hand and on the other a second river, the Ottawa, lost themselves. Cartier gazed at the silver streams stretching away to the west winding through unknown forests in the distance. They flowed from sources so remote that the Natives "had never heard of anyone reaching the head of them." We can well imagine that he asked himself, "Which way must I go to seek Cathay?

The violent rapids of La Chine removed any hope of voyaging by boat directly to the great cities of China. Cartier like Moses from Mount Nebo stared westward to the promised land upon which he would never tread. The French could go no further. The violent Lachine Rapids flooding downward at a speed of more than thirty miles an hour barred passage by the ship's boats,

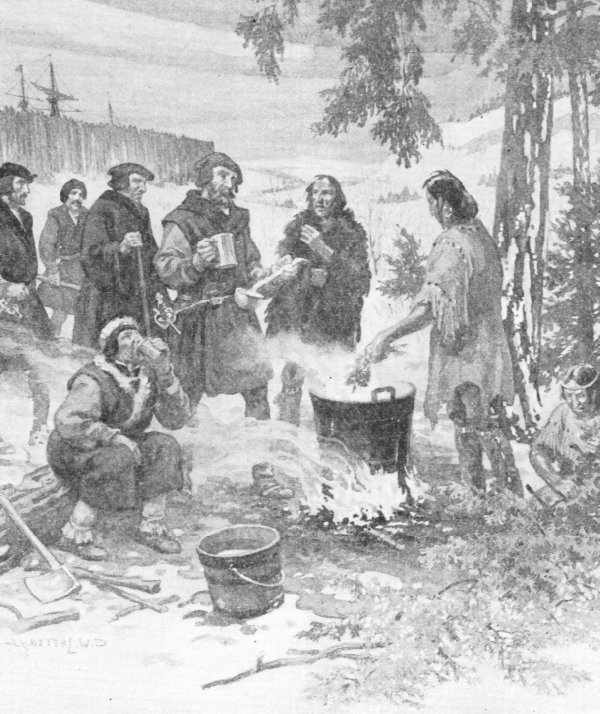

Cartier and company returned to Stadacona little knowing what the cold winter had in store for them. The smiling face of the forest land now frowned upon them. The winter proved to be a nightmare to the French. By January and February ice nearly four metres thick locked the ships in a frosty embrace. On land snow was a metre deep and sub-zero winds howled about their little settlement. Many fell ill and died. Penned up in their makeshift encampment and stricken with the dreaded scurvy, only ten of the hundred and ten remained healthy. During the siege of sickness "twenty-five of the best and most able seamen we had succumbed to the malady." The others escaped death from scurvy when Cartier learned the the Natives' carefully kept secret remedy: a brew made from white cedar leaves and bark that contained a high content of ascorbic acid (vitamin C). (Botanists still dispute the kind of evergreen used; some say hemlock, others cedar.) Whatever it was it cured the men in miraculous fashion.

|

|

The First Prescription In Canada |

Cartier used the time to observe and interrogate the Natives about their beliefs and habits. They had no domestic animals except dogs. Much of their meat was eaten freshly killed hence its high vitamin content. Only the surplus was smoked or dried to preserve it. Salt was not used at all. Cartier was intrigued by their habit of smoking and provided this description of their use of tobacco. "There groweth a certain kind of herb whereof in summer they make a great provision for all the year. They wear it about their necks wrapped in a little beast's skin made like a little bag with a hollow piece of wood or stone. At frequent intervals they crumble up this plant into powder, which they place in one of the large openings of the hollow instrument and laying a live coal on top suck at the other end to such an extent that they fill their bodies so full of smoke that it streams out of their mouths and nostrils as from a chimney. They say it keeps them warm and in good health and never go about without these things. We made a trial of this smoke. When it is in one's mouth one would think one had taken powdered pepper it was so hot." This was probably the white man's first experiment with tobacco and it occurred some fifty years before Sir Walter Raleigh began to popularize smoking in Queen Elizabeth's London.

Mutual distrust flared up in the spring of 1536. A quarrel had broken out between Donnacona and his rival Agona and Cartier was asked by Donnacona's son to eliminate Agona. Cartier decided he would "outwit them" by getting rid of Donnacona and his sons, who were a greater threat to the French, by taking them back to France. This would also permit Cartier to present Donnacona to the king so that he could tell him all the tales he had told Cartier regarding the wonders of Saguenay. These were tall tales for Donnacona enjoyed pulling the leg of the palefaces with fanciful stories about gold and silver. Now Donnacona was going to pay for his fun for Cartier kidnapped him and his sons along with four children who had been presented to Cartier by Donnacona. The Natives never saw Canada again.

The departure of Cartier and his men in the spring was really more of a flight from danger for the French had fallen out with the Stadaconans. Not unnaturally the Natives were somewhat disturbed by Donnacona's rather sudden departure from their midst and expressed their concerns to Cartier who sought to assure them that all would be well. After he "spoke thus to set their minds at rest," Cartier set sail for home on May 6th, 1536 in only two ships since the the Petite Hermine had to be abandoned for lack of crew to man it. The Frenchmen reached St. Malo on July 16, 1536. Five years were to pass before the lure of the Kingdom of Saguenay once again beckoned the Frenchmen.

Believing this kingdon would rival the wealth of the Spanish empire, King Francis I once again turned his attention to these new lands. To head the third voyage the king chose Sieur de Roberval whom he created viceroy and lieutenant-general of Canada. Cartier accompanied Roberval in the capacity of captain-general and master-pilot. With crew members recruited from the prisons, they were to proceed to "Canada and Hochelega and as far as the land of Saguenay."

In May 1541 Cartier was ready to leave before Roberval so he authorized Cartier's party to proceed on their own which they did in five ships. Cartier's crew contained no Natives. On arrival in Stadaconna Cartier informed Chief Agona that Donnacona had died, but that the others were all living lives of luxury in France as great lords and were unwilling to return to Stadaconna. In fact, all but one had died and her fate is unknown. The Natives were by no means satisfied with this explanation and despite Cartier's reassuring words, distrust permeated the relationship. The disenchanted Iroquois had every right to be outraged by this treachery which saw Europeans stealing people from their land and ended up having them steal land from the people.

Made wary by the worrisome attitude of Native warriors which changed from friendly and familiar to surly and suspicious, Cartier had constructed a palisaded and fortified settlement a few miles up-river at Cap Rouge which he named Charlesbourg-Royal. The Natives kept the settlement in a state of siege and Cartier's narratives on this trip closed with the following somewhat worried and wary comment.

"And when we arrived at our fort we understood by our people that the savages of the country came not any more about our fort and that they were in a great doubt and fear of us. Wherefore our captain having been advised by some of our men who had been at Stadacona to visit them that there was a great number of them assembled together caused all things in our fortress to be set in good order." They prepared themselves for any eventuality. The second winter in New France was passed as miserably as the first. A veritable war broke finally broke out between the Natives of Stadacona and the French near Quebec. The Natives attacked the habitation and boasted of killing some 35 Frenchmen. Cartier and company quickly departed for France in the spring of 1542 with a cargo of minerals he thought were gold and diamonds. The gold turned out to be iron pyrites and the alleged diamonds nothing but quartz. An old French proverb still used in Brittany and Normandy owes its orgin to Cartier's third voyage. "Faux comme un diamant du Canada." (fake as a Canadian diamond).< b>[See Below *]

The French crown sponsored the voyages of Jacques Cartier (1534,1535-1536, 1541-1542) in an attempt to find the Spice Islands of Southeast Asia, but apart from establishing French claim to important parts of what is today Canada, these trips achieved little. The settlements founded by Cartier and later by Roberval in 1541-1543 failed because they lacked an economic foundation and because the Native population was hostile to them. Nevertheless, Cartier did add materially to what was known about the new land. Not satisfied to sail up and down the Atlantic coast, he sailed boldly into the St. Lawrence exploring it to Montreal. His achievements were the beginning of far-reaching work, the completion of which fell into the hands of others. Cartier came to these coasts to find a pathway to the empire of the East and found instead a country vast and beautiful beyond his dreams - Canada.

It was oftimes the custom of officials of the port of St.

Malo to record the death of any townsman of note. In the margins of

documents dated September 1, 1557, there is written in the penmanship of

the time:

"This Wednesday about five in the morning died Jacques Cartier."

Cartier was sixty-six years of age. He had surveyed the coasts of the Gulf of St. Lawrence, described the life of Natives of northeastern North America and discovered the St. Lawrence, one of the greatest rivers in the world. He also marked the start of France's occupation of three-quarters of a continent.

NOTE

Maps of the 1560s showed the Caribbean islands in

approximately the right places. The name Florida appeared on a long

peninsula. A river called the St. Lawrence flowed out of a vague territory

labelled Nova Francia. And beside the river on the north lay an area

bearing the name: CANADA. From this time onward three main impulses drew

men to this tantalizing land: the dogged search for a water-route to

Cathay and the East Indies; a longing to convert Aboriginals to

Christianity; and the wondrous wealth of the new land itself.