foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

BROCK AT THE OUTBREAK OF WAR, PART 1

"Don't depend on the enemy not coming; depend rather on being ready for him when he does." Sun Tzu

In 1805 Brock was promoted to the rank of colonel and transferred back to Quebec. Shortly thereafter he left for England on leave and with the exception of this period, which extended from October 1805 to June 1806, Brock spent the remainder of his life in the land that history links with his name.

While in England Brock submitted a report to the Duke of York, Britain's commander-in-chief, on changes Brock believed would improve the efficiency of British forces in Canada. Desertion of troops to the United States was a continuing problem and Brock thought it could be reduced by placing veteran battalions comprised of reliable old soldiers at the border posts. After they had served out their term of enlistment, Brock recommended they be given land and furnished with farming implements and rations until they were able to provide for themselves. This would ensure a permanent,loyal military presence in the province. Some of his recommendations were accepted and acted upon.

|

|

Brock |

When Brock returned to Canada in June 1806 he assumed temporary command of troops in both provinces. He brought an invaluable quality extremely rare in the province: military leadership at once vigorous, imaginative and professional. He faced with the usual predicament of a defender: the necessity of spreading his limited troops thinly across a considerable front in order to ensure some defence everywhere. The invader, meanwhile, was free to focus his forces at any chosen point. Brock strengthened fortifications in Quebec and ensured the development of a marine department capable of action on Lakes Erie and Ontario by ordering the construction of ships for service on the lakes. His foresight fostered the existence six years later of a fighting force on the lakes that made the defence of Upper Canada possible.

Brock replaced Alexander Grant with George Hall as commodore of Lakes Erie, Huron and Michigan. The commodore oversaw the preparation of ships for military activity by readying them to transport British troops and by directing the positioning of guns and carronades on the various vessels. Hall's first major assignment was at Detroit when Brock placed him in charge of the batteries that battered Fort Detroit. For this service Hall was one of the few officers awarded a specially minted Detroit medal to recognize exemplary service there. Hall also oversaw the transportation of troops to the Niagara frontier along with their supplies and equipment.

Brock had the militia called out for training and recommended that a volunteer corps be created from among Scottish settlers in Glengarry. Nothing was done in this regard until 1812 when Brock became administrator of the province and recommended the raising of a Glengarry regiment to Sir George Prevost, the new military commander and Governor-in-Chief at Quebec. Prevost agreed and without waiting for approval from authorities in London ordered the formation of the regiment.

|

|

|

In 1808 Brock was appointed brigadier general and assigned command of troops in Montreal. At Montreal Brock spent considerable time in the company of the merchant princes, wealthy traders of the North West Company and the Hudson Bay Company whose combination now comprised an empire embracing an area of 4.5 million square miles. As a man of the world Brock enjoyed the creature comforts of life. These included the blazing comfort of a log-fire with its glow and crackle as the blizzard raged outside; the dim-lighted splendour of the spacious dining hall with its hewn rafters and the savage trophies of the explorers; the polished oak floor and carved ceiling hung with rare fur and gaudy feathers. All these things appealed to him. And when the rubber of whist was over, they lit up the fragrant perfecto cigars. The traders ransacked the world for the finest tobacco. As Brock savoured the soothing weed he was charmed by tales the traders told of the strange secrets of the wilderness.

On June 4th, 1811 Brock became major general and was "transferred to the province of Upper Canada on the staff of North America" with his headquarters at Fort George. This assignment to the wilderness was neither welcome nor wholly unexpected. Uncertain as to how long he would be in the boondocks, Brock explained in a letter home that "unless I take up everything with me, I shall be miserably off for nothing beyond eatables is to be had there. In case I provide the requisites to make my abode in the winter comfortable and then am ordered back to Quebec City, the expense will be ruinous. But I must submit to all this without repining."

Brock wished to familiarize himself with the upper water ways and shortly after arriving at York from Quebec he set out to see his new territory. From Niagara he travelled to Amherstburg, Detroit, Sandwich and returned over land to Ft. George. Brock's tour took him to Delaware and via the Govt road at Oxford on the Thames to Long Woods and Burford Plains, then to Brant's Ford and the Grand River. From Ancaster he travelled to Burlington at the head of the lake and then following Lake Ontario's southern shore he returned to Niagara.

|

|

A Bustard the heaviest of all flying birds |

Brock was very impressed with the resources of the country and in a letter to his "beloved brothers," he described it as "delightful country, far exceeding anything I have seen on this continent." The extent of the Great Lakes amazed him as did the fish therein and the wildlife round about. He shot big bustards and wild turkeys and watched as Indian fishermen pulled in whitefish ahtikameg (deer-of-the-water) from the lakes weighing twenty pounds. Stories were widespread of five hundred pounds of whitefish being taken with a scoop net at the rapids of Sault Ste. Marie in two hours. On one occasion in the lower Niagara River, Brock himself helped haul in a net full of the delicious fish.

As Brock's mind expanded so did his body. While "hard as nails" he was now inclined to be a bit portly. His face was fair and florid with a broad forehead and eyes somewhat small yet full and of a greyish hue. He had a charming smile and splendid white teeth. He read much and rapidly and was able to memorize passages in books making the deepest impression on him. History, civil and military, as well as maps were his strength. He pored over maps late into the night until he knew the country as well as the surveyor-general. For relaxation he devoured the robust beauty of Pope's Homer, regularly regretting that he never had a teacher "to guide and encourage him in his tastes."

While Brock found the country impressive, he was shocked to discover that morale of the Upper Canadians was at an all-time low. Their concerns he thought were less fact than fear. Defeat was dominant in most minds. Desertions were frequent, fortifications were run-down and the supply of arms was insufficient. The militia in many places existed only on paper and relations with the Native people was uncertain. It was a measure of the man that Brock was not discouraged by the problems he faced. His first action was characteristically vigorous, effective and brisk. He tackled the problems of discipline and desertion with energy and imagination.

Brock realized that the lack of training and troops limited the effectiveness of the sedentary militia and he introduced important clauses to the Militia Act which was passed on March 6, 1812. Flank companies were added to each militia battalion. They were to be fully equipped and trained six times a month. Brock hoped this would raise 1800 soldiers who would be "a better trained, loyal and dependable core in each militia regiment." He explained in a circular letter to all commanding officers that the role of flank companies was "to have in constant readiness a force composed of loyal, brave and Respectable Young Men to enable the government on any emergency to engraft such portions of the Militia as necessary." The flank companies were to be available for duty by the end of April 1812! These changes were successful and the flank companies proved to be the backbone of the militia during the war with several participating in a number of engagements. However, the backbone of the defence of Canada continued to be borne by the British garrison supported by the Canadian Militia which in time of conflict could be called up to augment the regular troops.

Brock endeared himself to the soldiers by acting on their behalf if regulations were irrelevant for existing conditions. Clothing was a case in point. Brock wrote,"Every man is provided with a great coat agreeably to His Majesty's regulations but as the great coat is worn on all occasions six months of the year it cannot in the strictest economy be made to last for the specified time." Troops soon learned they could depend on Brock for fair treatment. Of the 49th Brock wrote in 1812, "although the regiment has been ten years in this country drinking rum without bounds, it is still respectable and apparently ardent for an opportunity to acquire distinction."

Brock recognized what the lure of new life in the United States was to would-be deserters. His solution was the settlement of reliable, discharged, army veterans in the border regions where their property holdings gave them a vested interest in its security and welfare and where their military experience was invaluable in the militia in time of war. In the words of one colonel Brock was "strict, just and kind." His honorable and even-handed treatment of the men was amply rewarded. Discipline improved markedly and desertion was rare in units with which he had personal contact.

Relations with the Aboriginals were a vital factor in the defence of the country. A crucial most ticklish problem centred around them. It was necessary for Britain to maintain their friendship while at the same time restraining them from attacking the Americans which could result in an attack on Canada. Here again Brock laboured to improve matters. While he never sought to arouse Natives against the United States, he did attempt to ensure that in the event of war they would not be on the other side. In dispatches he emphasized the importance of making generous gifts to the various chiefs and delivering them at the appointed time. Brock's character and striking physical appearance impressed the greatest of all Aboriginal chiefs - Tecumseh.

Brock requested a thousand more men but when informed he would get none he reinforced Niagara with men under his command at Fort Malden and Kingston. He distributed 2000 American muskets to militiamen and fifty swords and fifty waist-belts to Volunteer Cavalry who signed up at York. He also dispersed "one hundred Horse-Pistols." He ordered the construction of a series of alarm posts and placed signal beacons on every bluff and headland along the river so that using fire at night and smoke during daylight hours warnings of attack could be quickly conveyed across the peninsula.

|

|

|

Brock pushed for the establishment of York as a Naval Yard which would gradually replace Kingston whose nearness to the border made it vulnerable to American attack. York had an ample supply of timber readily available and "a safe and commodious Harbour capable of affording shelter to any number of vessels and is easily fortified as the entrance is narrow." If fortified and well-garrisoned York would be secure from any sudden assault.

Despite his heavy load of military responsibilities Brock chafed at his idleness during much of the service in Canada. He found time tedious and in letters to his brothers lamented being "buried in this inactive, remote corner" of the world while fellow officers saw action aplenty in the wars of Europe. Brock felt fate had decreed that his time and talents were being wasted on inaction. He had been "placed high on a shelf" and was envious of his brother, Savery, who was then serving in Europe in the prestigious role as aide to Sir John Moore, the general commanding the British army battling Napoleon. [See Below *]

|

|

Napoleon Bonaparte |

The Peninsula War was the most direct road to public recognition and military honour and while other British officers were winning laurels serving there under the Duke of Wellington, [**] Brock languished in the obscurity of Upper Canada pining for a post that would bring him eminence as a soldier and, perhaps, he wrote wistfully, even "the honour of the Bath." [***] Brock feared the field of fame was being harvested by others. The wheel of history turned, however, and gave him the opportunity to manifest his luster as a leader. He was to achieve eternal honours and go down in history wreathed in glory and imperishable renown.

|

|

Napoleon & Wellington |

In a letter to brother Irving in 1811 Brock stated that after spending ten years in Canada he was more than ready to leave. He continued to believe his chances for fame would be better in Europe where officers of his age and rank were winning distinguished reputations. "I wish to join Lord Wellington." He consoled himself with the expectation that his application for transfer to Europe would soon be approved.

|

|

Duke of Wellington |

Despite bemoaning his fate in the forest, Brock felt a sense of mission for he was mindful of and constantly concerned with the military safety of Upper Canada. Anxious about the military's slow progress in cutting out new roads which he deemed "essential work," Brock requested the replacement of the two oxen that had been used "in clearing the vast quantity of heavy timber which grows close to the Garrison." It seems the other two oxen had mysteriously disappeared.

Prevost, who had arrived in Quebec in October and whom Brock had not yet met personally, was reluctant and indecisive by nature. He feared the weight of his sword. He saw the odds in everything and missed the evens. It was said of him that he was "one of those men who succeed half-way up and fail at the top." He was compared to a man in a minefield wondering where to put his foot. In a cautionary letter to Brock dated July 10, 1811, Prevost wrote, "Our numbers would not justify offensive operations being undertaken." Prevost's words of caution resulted from his awareness of Brock's differing views about what the local military reaction should be to any attack by the Americans.

Brock knew war's very objective was victory, not prolonged indecision.Brock knew war's very objective was victory, not prolonged indecision for in combat there was no substitute for success. A man of thought and pen with the sure instincts of a born soldier, Brock was able to identify the essential elements of the strategic situation. Wherever he went decision and order followed. In December 1811 in anticipation of an American invasion, Brock submitted a remarkable dispatch to Prevost. In it he commented on the possibility of war with the United States and asserted the only hope for Canada lay in prompt attacks upon two American military posts, Michilimackinac and Detroit.

Brock, like Major General James Wolfe, recognized the importance of offensive action. Wolfe wrote, "An offensive, daring kind of war will awe the Indians and ruin the French." Brock believed that victories at these posts would impress the Natives. He hoped it would as well arouse an apathetic militia and enhearten the people of Upper Canada about whose morale and loyalty he was deeply concerned. He fully expected the main attack to come between Niagara and Fort Erie. In order to reassure the timid who were rendered nervous by the recent clamors, he urged the presence there of a strong regular force. Brock had a keen perception of Fortune's wheel and this fine foresight convinced him that "all other attacks will be subordinate or merely made to divert our attention."

|

|

Sir George Prevost |

Unlike Prevost Brock's preoccupation was not with how to avoid defeat but how to inflict it.

But when the blast of war blows in our ears

Then imitate the action of the tiger

Stiffen the sinews, summon up the blood

Hold hard the breath and bend up every spirit ...To his full height!

Brock might have been more circumspect regarding his offensive recommendations if he had been aware of Prevost's somewhat cautious character. While Prevost admitted to Brock that a quick strike would be preferable "rather than receiving the first blow," Prevost wished war could be avoided and was reluctant to make the first strike. He had about him the brooding hesitancy of a man waiting for something that had already happened. While Prevost was reluctant to initiate aggressive actions himself, he fortunately left military decisions in Upper Canada largely to the discretion of Brock. Distances were great and communications slow and Brock, whose agenda was set by the winds, was able during the first four months of the war to put his own ideas into operation. While there was little help from Prevost, there was little hindrance.

Initially Prevost had refused Brock's request for a transfer to England but at the end of January 1812 he aproved Brock's application for a service assignment in Europe. Prevost added, however, that he hoped Brock would not act on it. By now Brock was well aware of the clouds of war looming over the land and he decided he wanted to be part of the coming conflict. In a letter to Prevost he requested,

In His Own Words

"to be allowed to remain in my present command."

Brock's request was speedily granted and he immediately undertook to prepare the people of the province for the dangers to come. In so doing Brock was responding to the summons of history. The province's hopes hung on his destiny.

Brock's brothers kept him supplied with goods he could not get in Canada. He wrote to Irving thanking him for the things sent all of which arrived safely, "with the exception of the cocked hat." Brock was disappointed because, "from the enormity of my head, I find the utmost difficulty in getting a substitute in this country." When the hat finally arrived it was no longer needed. Brock was dead.

|

|

Brock's Cocked Hat on display in the Niagara Falls Museum |

|

|

Note regarding Brock's Cocked Hat |

Brock established his headquarters at Fort George with a fellow officer Lieutenant Colonel John Murray and his wife. The two men had many mutual friends, one of whom was Colonel J.A. Vesey, at whose home Brock had stayed when he last visited England. In a letter to Brock in April, 1811, Vesey wrote, "I wish I had a daughter old enough for you. You should be married, particularly as fate seems to detain you so long in Canada - but pray do not marry there."

Brock found the new posting a lonely one. In a letter to his brothers, he said it deprived him of the company of "a lively, communicative associate" whom he had known in Montreal. Notwithstanding the word 'lively,' there was no indication this might have been a female.

In His Own Words"I hardly ever stir out and unless I have company at home, my evenings are passed solus."

Brock was an avid reader and undoubledly most solus evenings found him deeply engrossed in a book. He read widely and rapidly and memorized passages that made the deepest impression on him. History, both civil and military, were favourites and he found maps fascinating. He would pore over them late at night until he knew the country as well as the Surveyor General.

For variety, Brock read with relish the robust beauties of Pope's translation of Homer's Iliad.

[

In Pope's translation of this Greek classic, he highlighted the play of vowels through his lines. His most potent effect is assonance - the lazy music, for instance, of the three long e sounds (ease, heaps, grieves) in this: ["Thus at full ease, in heaps of riches rolled, What grieves the monarch?] (Samuel Johnson pronounced Pope's translation the greatest ever achieved in English or in any other language.)

|

|

Alexander Pope |

|

|

Homer |

While Brock regularly regretted that he never had a master "to guide and encourage him in his tastes," he's considered to have been a well, self-educated man.

Brock had two distinct sides: one official and public and one personal and private. In spite of his feelings of isolation suffering many solus evenings, Brock was a popular member of society. The officers' mess at Fort Niagara provided frequent opportunities for pleasurable evenings for inhabitants of both town and country. Brock also regularly rode out and about to visit with residents in the countryside and warmly welcomed their invitations and hospitable fare. An example of Brock's active, personal participation in the life of the community was reflected in his and his officers' liberal financial support of the building fund for St. Mark's Church in Niagara, which was completed in 1807.

Nor was he any stranger to revelry, for he reciprocated local hospitality by hosting at least one big party for the people. He particularly enjoyed balls and delighted in dancing waltzes and mazurkas. In a letter written to him by Colonel Kemp, an old friend of Brock's in Quebec, Kemp commented, "I have just received a long letter from Mrs. Murray giving me an account of a splendid ball given by you to the beau monde of Niagara and its vicinity. The manner in which she speaks of your liberality and hospitality reminded me of the many pleasant hours I passed under your roof. We have no parties now."

As Brock's social life expanded, so did his waistline and while he claimed to be "hard as nails," he was now inclined to be a bit portly. Fair and florid with broad forehead, his eyes were somewhat small yet full and a greyish hue. His charming smile showcased splendid white teeth. When Brock became administrator of Upper Canada it was expected that he would become the dispenser of official hospitality at York. Consequently, there were balls and receptions most months, the printed invitations to which were delivered by soldier batmen or personal servants. The elite of the little community attended events at the Officer's Mess at the Garrison and occasionally for the most senior officials at the Governor's House hosted by the handsome Brock.

Brock's good humour and affability won the hearts of men, women and children and his visits to homes in the area were hailed as happy events. His charismatic presence brought such pride to the hosting homeowners that the chair on which he sat or the cup from which he drank were proudly preserved as notable mementoes of the special occasion. They became family treasures. One example of a prized possession was the following letter of Brock's written from Quebec in Sept. 1805. It was retained by an Ontario family for many years before finally being sold at public auction in New York in 1925. Written during Brock's early days in Canada, it is probably the only letter of his from that period still in existence.

In His Own Words"I look upon the situation of England as critical in the extreme. Bonaparte laughs at the whole world. Who could have conceived that his fleets could traverse the ocean with the impunity which we have lately witnessed? It is true they have gained no great glory in their career, but their men acquire by these midnight excursions nautical knowledge which by degrees will prepare them to undertake with greater likelihood of success more important enterprises. They become more formidable every day they are allowed to keep the sea for by practice they acquire confidence which is the very soul of success. Let us hope the time is fast approaching when an opportunity will be offered of grappling with them. Then the Lord have mercy on them for I trust we never will."

A souvenir of sorts associated with St. Mark's church cemetery is Brock's Seat. This boulder, according to one source, was once located on the western bank of the Niagara River at the foot of Victoria Street opposite Fort Niagara. On this large, flat-topped stone, Brock would sit and study the citadel across the river, perhaps, planning the best way to take the fortified garrison. In November 1893 a historically-minded citizen relocated the stone to St. Mark's cemetery where it can be found today. On the occasion of its relocation the following sonnet was written on the subject.

Brock's Seat

"Yes! Place it in the old churchyard, this stone

In honoured memory of heroic Brock,

Whose seat it was, oft pondering the shock

Of war to come, while lake and river shone

With sunset glory. His clear eye alone

Foresaw the way to victory - to unlock

The people's hearts and fill them from his own.

Yes! Set it fitly in the sacred ground,

And every year with garlands be it crowned,

Forgetting never, our deliverance stood

At the full price of his devoted blood,

The price he paid, amid the battle roar,

As Queenston Heights bear witness ever more."

|

|

Brock's 'Seat' |

Fort George [*****] consisted of a palisade loopholed for guns banked with earth twelve feet high outside of which was a dry ditch. There were six bastions faced with timber and plank. Troops were lodged in blockhouses which afforded barracks for 220 men. There was a spacious building for the officers' quarters as well as an officers' kitchen. In addition there were storehouses, a guardhouse and a solid stone magazine with an arched roof for powder storage. The fort was defended by mortors, howitzers and cannons of various calibre, two heavy 24-pounders being the biggest then available.

Cannons were manned by five soldiers while another four kept them supplied with ammunition.

No. 1 a sergeant, commanded and aimed the piece.

No. 2 the sponge man to the right of the barrel wiped it out with a damp fleece on a wooden staff to extinguish any smoldering debris left by the previous shot.

No.3 the loader on the left then pushed the ammunition - usually a serge bag of powder attached to the projectile by a wooden sabot - into the muzzle. The sponge man reversed his staff and rammed the charge home while

No. 4 the vents man standing by the breech blocked the touch-hole with his leather thumb-stall to prevent a rush of air which might fan any embers that had been missed by the sponge. The vents man filled the hole with finely ground gunpowder.

No. 5 fired it on command by applying a portfire, a length of quick-match on a wooden handle applied to the touch-hole. All members stood well clear as the gun fired because it would leap back on its wheels crushing feet as it did so. Before it was loaded again it had to be pushed back to its original position.

In late autumn 1811 as a result of the temporary absence in England of Upper Canada's Lieutenant-Governor Francis Gore, Brock was appointed provisional president and administrator of the province. In the final year of his life he occupied the offices of both military commander and head of the civil government. Brock was richly endowed with the attributes of his office: a commanding presence; a shrewd judgement; a resolute nature and a martial ardour. During this tense and anxious time with the United States, there was widespread backing for Brock's appointment as he recorded in a report to General Prevost. "The people of the province were much heartened by the appointment of a military man to administer the government."

Critical moments often produce the man to match the need and in this instance and fortuitously that individual proved to be not only courageous but also clever. Shortly after this larger-than-life leader became administrator of Upper Canada, it was said that a "great comet" streaked across the northern sky. Some declared it foretold of a cataclysmic event that was to occur in the colony. The long-tailed celestial body boded well and ill for Isaac Brock. In the cataclysm to come fortune found him in a backwoods posting and selected him to change the course of history. It also took his life.

As war clouds hovered over the horizon Brock grew increasingly fearful of the negative attitude of the citizenry. While he did not doubt that "a large portion of the population are sincere in their professions to defend the country," defeatism was spreading across the colony like a cold mist. Nothing could be taken for granted at this perilous period, not even the certainty of a greater part of the population's loyalty. In fact, there were times when Brock felt that far from affording him support, many in the province seem to serve solely to supplement the number of his enemies.

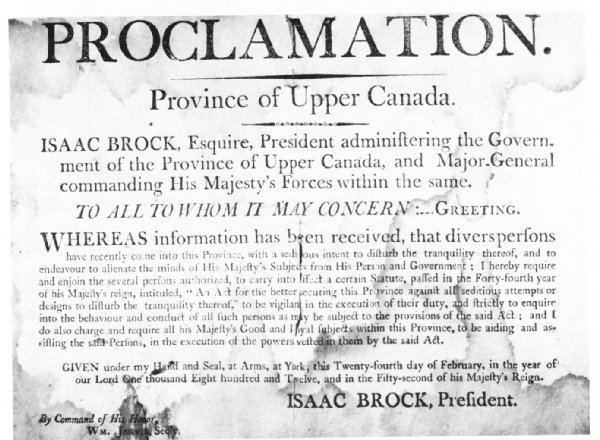

Warnings were widespread for the public "to be on guard against the treacherous acts and insidious language of American emissaries." Concerned that loyalty would be lessened even more by trouble-makers from the States, Brock issued the following proclamation to alert citizenry to be watchful for those who by stealth and trickery would seek to weaken further the will of those already wavering.

|

|

Brock's Proclamation, 1812 |

Some of the citizens were fence-sitters, individuals whom Brock called 'cool calculators,' "those who consider our means inadequate but who would readily take an active part were the number of regular troops increased." Well aware of the adverse and hostile currents that surged about him, Brock braved the unknown hoping for the best and believing "the majority would prove faithful." If not, he warned, "It will be utterly impossible to preserve the province with the limited number of military."

|

|

Facsimile of Brock's Proclamation, 1812 |

Brock's move from Fort George to York to assume the office of president was accompanied by a large entourage of personal staff. In a letter to Lord Liverpool dated October 9th, 1811, Brock confirmed that he had been sworn in as a member of the Legislative Council and assumed the administration of the province.

|

A popular ballad of the day, The Bold Canadian, marked his move.

"At length our brave commander,

General Isaac Brock by name,

Took shipping at Niagara

And unto York he came.

Says he, 'Ye valiant heroes,

Will ye go along with me

To fight those proud Yankees

In the west of Canada?"

Brock had to endure widespread negative opinion in silence because the extent of citizen support could not be argued out in public or in parliament. He needed swords as sharp as those he expected to face, but he received no additional men, money or materials. He even lacked specie, that is, money in coin, so he was required to issue special bank notes. His response was a resolute facing of facts.

To add to his problems during this period of unparalleled danger, Brock was faced with an unreceptive Assembly. His fears were confirmed when he met and addressed the Legislature for the first time on the 3rd of February, 1812. He prepared what he thought was an inspiring message hoping the Speech from the Throne would motivate the members to act with spirit and resolve. He urged the Members to go forth in the spirit of the age. It was a time when no one felt sure of his life, land or livelihood. It was, therefore, a measure of the unpopularity of his policies that so persuasive speech fell largely on deaf ears.

"Honourable Gentlemen of the Legislative Council and Gentlemen of the House of Assembly: I should derive the utmost satisfaction the first time of my addressing you were it permitted me to direct your attention solely to such objects as tended to promote the peace and prosperity of the Province." Brock referred to the "glorious contest," Britain's war with Napoleon in which the British Empire was then engaged, and said that instead of receiving grateful thanks for Britain's noble attempt to defeat the tyrant, Napoleon, she received only accusations, insults and threats of war from other countries. While "cool reflection and the dictates of justice may yet avert the calamities of war," Brock said he was preparing for the worst while hoping for the best. His policy was neither defiance nor deference but defence. He appealled to each citizen's loyalty, pride and patriotism. "When I address you as legislators, I speak to men who in the day of danger will be ready to assist, not only with their counsel but with their arms. Principally composed of the sons of loyal and brave bands of veterans, the militia, I am confident, stand in need of nothing but the necessary legislative provisions to direct their endeavours."

Brock attributed external threats "to envy the province's prosperity had awakened in others," and assured legislators that "Britain would always be there with her powerful protection." The unspoken question was would they be there for Britain. Brock hoped to shame the legislators into providing solid support by reminding them of the fair treatment and the good fortune they had received under British rule.

"Where is the Canadian subject who can truly affirm to himself that he has been injured by the government in his person, his property or his liberty? Where is to be found in any part of the world, a growth so rapid in prosperity and wealth as this colony exhibits? We wish and hope for peace but must be prepared for war. We are engaged in an awful and eventful contest. By vigor we may teach the enemy this lesson: that a country defended by free men, enthusiastically devoted to the cause of their King and constitution cannot be conquered. Heaven will look favorably on the manly exertions which the loyal and virtuous inhabitants of this happy land are prepared to make to avert the dire calamity of losing the support of Britain."

Legislation passed at this session did include an act to reduce or eliminate desertion from his Majesty's regular forces by granting a bounty to anyone who apprehended deserters in the Province. This was needed to offset American enticements which lured soldiers across the river with promises to exchange hard service and inhuman discipline for a comfortable life in the United States. Another act dealt with the raising and training of the militia. While Brock had real doubts about many in the militia, he knew that in war morale was everything so he praised the militia whenever he could for its readiness to respond when summoned to arms."Our Militia have heard that voice which calls them to defend their country and obeyed it. We look to the Militia and to our regular forces for our protection."

In his correspondence to Prevost Brock was of a different mind. He expressed concern about the poor conduct and lack of enthusiasm displayed by the militia. When some learned they would have to leave their farms during harvest and face the enemy some distance from their families, they refused to march. Their negative attitude reflected the the feeling of hopelessness and alienation existing among the general population. Brock apprehension arose "not from anything the enemy can do, but from the disposition of the people."

Little wisdom and less foresight existed among the legislators who sat inert and helpless while the helm of the colony swayed this way and that. The responsible authorities gazed at the crisis with vacant eyes. In the face of this defeatism, But for all his eloquence, Brock's appeal was received in sullen silence. Despite his exhortation to act they sat as still as midnight. Brock might very well have resigned himself to the inevitable and lashed out in frustration and contempt at the pessimistic population. But some individual had to dominate and do and that person was Isaac Brock. Instead living on his nerve, Brock assumed the task history had assigned him and adopted a public approach that contributed greatly to the successful defence of the province. His "daring and imaginative plan" was to "act with the utmost liberality as if no mistrust existed." Putting on a brave face he adopted an upbeat attitude and emphasized the positive by praising the militia for its readiness to respond to his appeal.

With respect to his requests for measures to put the province on a war footing, Brock found the fifth parliament in its final session in February and March 1812 less than accommodating. The last general election before 1812 had produced an Assembly "nearly equally divided between Blackguards and Gentlemen."¨ The 'Blackguards' included some outright supporters of annexation by the American republic. Belief was also prevalent that a clear majority of the residents anticipated that in the coming struggle, Upper Canada would be forced to yield to the might of the United States which in 1812 had a population of 7.5 million people living in 17 states and 6 Frontier territories. By comparison the Canadas contained 500,000 people.

Brock and the legislature held different views on the crisis. It demanded as far as Brock was concerned that the keenest eye, the surest hand, the most undaunted heart be risked and sacrificed. To him moderation in time of civil confusion was a crime. To many of the legislators Brock's cry of necessity demanding stern measures was tantamount to a tyrant's plea. Brock's passionate appeal for the passage of emergency legislation he deemed critical to wartime survival fell on deaf ears. Of the 23 members, thirteen opposed his plans. Brock wanted habeas corpus to go west for awhile, but he failed utterly to convince the Assembly to suspend the Habeas Corpus Act [******] or to implement partial martial law. He felt these were necessary to free him from the legal restraints of the judicial process should he deem it necessary to hold political prisoners without trial or to summarily incarcerate any disloyal elements in the population.

The Assembly's reluctance to surrender its civil liberties was not surprising. Members were unwilling to relinquish their basic rights even though they knew it would be difficult for Brock to cope with the crisis while at the same time having to worry about a detained person's civil liberties. Brock obviously felt he needed manoeuvring room to deal with dire emergencies, but a majority of the legislators were reluctant to yield their constitutional safeguards. Even the most loyal supporters were freeborn Britons, who while firm in their allegiance to the Crown, were also resolute in their commitment to the rights of property and due process of law.

Arbitrary actions on the part of the army were feared and those who opposed Brock's appeal had real reservations about giving non-elected authorities dictatorial powers. One of these was one James Durand, a loyal subject at whose home Brock had stayed when he was en route to Detroit. Durand, a captain of a flank company in the 5th Lincoln Militia who distinguished himself at the battle of Queenston Heights opposed the suspension of habeas corpus and the imposition of martial law because "it closed the lips of most of our people and compelled them to bear the kicks and cuffs of those who are used to overbearing tyranny." He resented the property damages he had suffered when he billeted British soldiers on his farm and disliked even more the loss of civil liberties that prevented him from criticizing the military's actions.

Citizenry believed they had good reason to be wary of suspending the Habeas Corpus Act and instituting martial law. During the election of 1817 one candidate recalled the indignities suffered by citizens during the war. "Your political vessel freighted with your laws and liberties was blown about to and fro at the will of the military storm. Magistrates abandoned her to the merciless tempest." Guards stopped wagons with provisions and impounded them leaving hungry families. People were arbitrarily imprisoned where "they wasted away in a shameful state in the York gaol." He chastised the authorities for not explaining why "the prize money due to soldiers for the capture of Detroit" had been so long delayed.

The Legislature's reluctance to grant Brock's requests may also have been due in part to the bitterness that resulted when Brock objected to the Assembly's contempt proceedings against a man named Nichol who had challenged the authority of the House of Assembly. When Brock first arrived in Upper Canada in 1804-05, Robert Nichol, "a mean-looking little Scotsman who squinted very much and kept a retail store of small consideration" at Fort Erie, became acquainted with him. Brock asked Nichol to prepare "a sketch of Upper Canada showing its resources in men, provisions, horses, etc." His report turned out to be very accurate and very valuable. Nichol also undertook the extremely difficult job of arranging for the transportation of all military men, supplies and equipment to southwestern Ontario in preparation for Brock's assault on Fort Detroit and for the next three years his efforts on behalf of the province were unequalled. Because Nichol had served him faithfully with various military matters, Brock came to his defence against what Brock termed the "inordinate power assumed by the House," which he described as a "palpable injustice and the machinations of a licentious faction."

Brock was denied a change in the Militia Act which would have required militiamen to renounce allegiance to any foreign power before they were given arms. He managed only to get an amendment to the Militia Act permitting him to reorganize the militia. In angry frustration he wrote a friend in Montreal

In His Own Words

"The population is essentially bad. A full belief possesses them all that this province must inevitably succumb. What a change an additional regiment would make in this part of the province. Most of the people have lost all confidence. I, however, speak loud and look big." Brock's letters to his family were interspersed with critical comments about being limited to defensive operations and deprived of those reinforcements which he thought should have been sent from Lower Canada.

Brock dissolved parliament on the 5th of May and authorized new elections, hoping as one person put it that the new assembly might be "composed of well-informed men who are well affected to the Government." Brock was determined to get a loyal and more compliant Assembly on the eve of war. The new elections were called early in June 1812, the main issue being whether or not to support Brock's request for repeal of the Habeas Corpus Act. Repeal candidates were largely successful with only six of the old Members being returned. Meanwhile the hopeless, dull, remorseless drift to war continued. The sands of peace were running out fast.

Finally the fearful sword was uplifted in flashing menace when word that war had been declared on June 18th reached Brock on June 25th. The messenger who informed him had travelled by relays of horses and had out-raced the official American courier and brought word to Fort Niagara within twenty-four hours. Brock had just been offered a company of farmers' sons with their draught horses in order to equip a car brigade under Captain Holcroft of the Royal Artillery. It was immediately accepted.

In the Niagara region the news was greeted with consternation on both sides of the border, where residents were accustomed to "habits of friendly association." Despite this there were immediate apprehensions regarding American citizens in Canada and they were ordered to leave Quebec City, the only permanent fortress in Canada where 2300 regulars were posted. Prevost considered the security of the city to be the key to the defence of Canada. Upper Canadians were stunned and apathetic now that war had comea and as time passed defeatism grew, desertions from the militia increased and some militiamen simply refused to march. Something had to be done to rouse the residents and impress the apprehensive people of the countryside.

With Evans Brock's brigade major and his aide-de-camp, Captain Gregg, Brock hastened to Fort George. In response to the call to duty some 800 militiamen in the Niagara Peninsula arrived to supplement the 500 regulars of the 41st Regiment at Ft. George, Brock's headquarters. There were no tents for the men and blankets, hammocks and kettles had to be purchased from local merchants. Militia flank companies were posted along the frontier. Comprised of forty men and a captain for each Upper Canadian community, the men served without pay, drilled six times a month and some trained to function as scouts and raiders. Other "most active preparations for defence" included orders to the militia and words of encouragement from Brock to keep up the nerve of his men. Welcome assistance in the form of a few new troops and military stores arrived from Lower Canada. Brock seriously considered an immediate attack on Fort Niagara, later assuring Sir George Prevost that it could be "demolished when found necessary in half an hour." He was reluctant it initiate this action without the sanction of his superior, so he contented himself with making preparations for offensive or defensive movements as circumstances might require. By the 3rd of July the "car brigage" was completed with horses belonging to gentlemen "who spared them free of expense."

The tense times often resulted in friend distrusting friend because loyalities were divided, even in the House of Assembly where one former member defected to the Americans. Tempers flared too. A British officer threatened to burn the houses over the heads of any who did not answer his call to join the militia. Careless talk caused trouble. According to one member of the Assembly "times are too dangerous for a man to open his mouth. Anxiety was pervasive and suspicions far-reaching. Casual comments often led to serious consequences as Roger Conant discovered.

Conant, a resident of Darlington in Upper Canada, was requisitioned by British officers to take a load of war materiels to York. After completing the task, Conant dropped into a hotel for refreshments where he joined a number of other citizens chatting around the fireplace. Talk turned to the war and Conant casually remarked that the war was unfortunate for many people and while he declared his support for Britain and Canada, he thought Britain's searches of American vessels were arbitrary. No sooner had he uttered this comment than it was conveyed to the local military commandant at Fort York. The next morning Conant was arrested, brought before a court-martial and fined 80 pounds. He managed to pay the fine and was able to return home where he continued to serve in the ranks "duly and faithfully."

The opening of the war saw Brock faced with four serious problems: the population, a large part of which was of alien origin; an Assembly reluctant to adopt war measures; a militia in the western districts that had little stomach for real fighting; and wavering Native allies who were difficult to control. He faced a fifth difficulty: an over-cautious superior in Prevost.

It is said that everything has its decisive moment; the trick in life is to identify and act at that moment. As soon as Brock received word of the declaration of war, he acted. In late June, Brock dispatched William McKay, an Indian Department official, from Montreal to St. Joseph Island with secret instructions to Captain Charles Roberts, commander at Fort St. Joseph. He arrived there in a mere eight days.

|

|

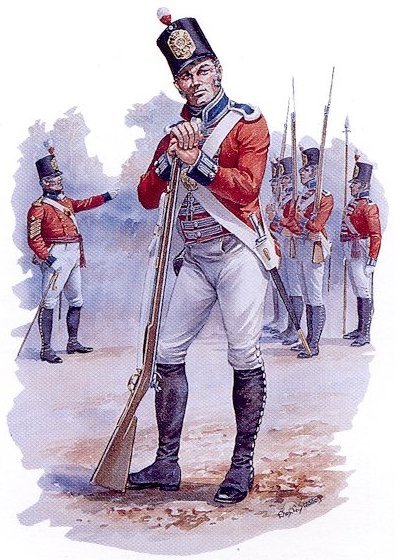

British Soldier, 10th Royal Veteran Battalion at Fort St.Joseph |

The Royal Veteran Battalions were units of garrison troops made up of older soldiers still able to stand guard and give other useful service. The 10th Battalion was raised in 1806 for service in Canada. Although not intended to serve in the field, the veterans were the only regular troops at Fort St. Joseph at the start of the War of 1812 and were part of the British surprise attack that captured the American Fort Mackinac.

Fort St. Joseph was a remote, isolated posting to which no man went volunarily and to which few wanted to be assigned. An incensed Brock used it on one occasion as a form of punishment when he banished James Cawdell, an ensign in 100th Foot. Cawdell, who was stationed in York where his friendship with the province's discontented attorney general, William Firth, angered Lieutenant Governor Gore. When Brock consequently assigned him to regimental headquarters at Fort George. the "irritated" subaltern wrote a satirical piece on Gore called the 'Puppet Shew.' Upon hearing erroneously that he too had been the object of Cawdell's satire, Brock banished the supposed insubordinate ensign to St. Joseph Island, "the Military Siberia of Upper Canada". Brock brooked no nonsense - real or imagined!.

|

Brock authorized Roberts to use his own judgement as to whether or not to attack the American post at Michilimackinac. Roberts decided to take the offensive. With 45 Redcoats, 180 Canadian voyageurs and some four hundred Aboriginals that included Ojibwa, Ottawa, Sioux and Winnebago warriors, he departed at 10:00 a.m. on 16 July. By what Roberts described as "the almost unparalleled exertions of the Canadians who manned the boats," they covered the fifty miles by 3 a.m.the following morning. After landing on the north shore of Mackinaw Island, they muscled a 6-pounder two miles through heavy timber and onto a high ridge behind the fort.

|

Roberts fired one shot to awake Lieutenant Porter Hanks and his sixty-one artillery men and then sent a flag of truce to demand their surrender. Hanks with his small detachment of regular artillerymen was no hero and being unaware of that war had been declared, capitulated without firing one shot for "the honour of the flag." In addition to the surrender of some 60 regulars, the British received seven cannons and a warehouse full of supplies that included: flour, port, vinegar, salt, candles, soap, thousands of dollars of trade goods and furs as well as a large quantity of liquor.

The tiny group of victors waited two years before "the first dividend of the proceeds of the prize property captured from the enemy at Michilimackinac" was approved. Each private received ten pounds. By contrast the booty received from the capture of Fort Detroit the following August was only three pounds per soldier. Native warriors received blankets, other goods and guns. |

|

Fort Mackinac [on the straits between Lake Michigan and Lake Huron] |

At noon on July 17th the American colours were hauled down and those of His Majesty hoisted. The second article of the terms of capitulation stated: "The garrison shall march out with the Honours of War, lay down their arms and become prisoners of war and shall be sent to the United States of America by His Britannic Majesty, not to serve again in this war until regularly exchanged and for the due performance of this article the officers pledge their word of honour." In his report to Brock, Roberts related the measures he had taken and commended "every individual engaged in this service." Suffering second thoughts about his conquest, Roberts added, "I trust, Sir, in thus acting I have not exceeded your instructions." On the contrary Brock must have been overjoyed with his officer's initiative and ecstatic to learn of the bloodless victory.

The shot aimed at a crow brought down an eagle. The effect of this tiny triumph was immediate, far-reaching and profound. News of it raced along the network of forest trails and waterworks till every wigwam was in awe at its startling success. Now the British held the key to the west in one hand and an irresistible sword in the other. Western Natives who were already friendly with Britain quickly confirmed in their allegiance and the redcoats won the loyalty of wavering tribes in the area west of Lake Michigan. The Aboriginals rose like a flood tide. If a side was to be chosen in this white man's war, let it be the British. The Native warriors seemed as natural allies as the swamps and forests. They had fought in every war and to have kept them neutral was beyond the power of man.

This Aboriginal alliance with British brought pressure to bear on Brigadier General William Hull at Detroit, who on the 12th of July 1812 crossed the Detroit River with the bulk of his command and took peaceful possession of the village of Sandwich. In a pompous proclamation Hull promised Canadians that "the invaluable blessings of civil, political and religious liberty were now theirs. The arrival of an "army of friends offered Peace, Liberty and Security. Your choice lies between these and War, Slavery and Destruction. Choose then but choose wisely." Brock received word of Hull's invasion on July 20th and a copy of his proclamation with word of its effect among some residents of the area. While Hull had invaded the province on the 12th, Lieutenant Colonel St. George allowed three days to lapse before dispatching word of this to Brock.

Brock commented on this in a letter to Prevost dated July 20th. "It is strange that three days should be allowed to lapse before sending to acquaint me of this important fact. Hull's insidious proclamation herewith enclosed has already been productive of considerable effect on the minds of people. In fact, a general sentiment prevails that with the present force resistance is unavailing. I shall continue to the utmost to overcome every difficulty." Unable to leave York because of the pending parliament, Brock instantly recalled a portion of the militia he had permitted to return home to gather the grain harvest and dispatched Colonel Procter of the 41st Regiment with such reinforcements he could spare from the Niagara frontier to assume command at Amherstburg. He also issued a counter-proclamation.

Brock had high hopes for the new parliament he had summoned into an emergency session which lasted from 27th of July to August 5th, the shortest session on record of the Upper Canadian parliament. It was widely known that General William Hull had invaded the southwestern part of the province where public alienation was pervasive. The district of London in particular was described as "the most turbulent and apparently dissatisfied." It remained so until until death and departure had eliminated the American settlers who were most discontented. While the settlers generally kept their disgruntlement hidden, there were many who feared they would suffer worst in a war they considered un-winnable and as a result when war was declared they simply deserted to the enemy.

For many American settlers in Upper Canada Hull's invading army created a crisis of allegiance. While a number remained silently on their farms, some supported their invading countrymen and when Hull's forces retreated across the border they departed with them. Some actually joined Hull's forces and led raiding parties against their former neighbours. "The enemy's cavalry," Brock reported to Prevost, "amounts to about 50 led by a desperate character named Watson." Other residents promised not to resist the American invaders if their properties were spared and several villages actually sought Hull's protection. A handful of Americans were arrested and in 1814 were tried for treason at Ancaster.

Hull had every reason to believe that many of the Americans who had recently arrived in the western district of Upper Canada would welcome, not resist his advance. Some sixty did and Hull sent them to their homes promising his protection. Even three members of the Assembly - two American and one British-born - crossed over to the enemy. The latter, a man named Joseph Willcocks, organized a force called the Canadian Volunteers which fought on the American side. Willicks is believed to have had a hand in the burning of Newark in December 1813.

Even those who disdainfully rejected Hull's proclamation harboured the horrifying thought that the province must surely succumb to superior American might. It was simply a matter of time. Despite this dispirited outlook a great many Canadians were outraged by Hull's pompous proclamation. Brock knew that courage like fear was contagious and he attempted to raise the spirits of these people with a rousing reply issued from Fort York. Brock's proclamation was intended to arouse both the pride and resentment of Canadians.

In His Own Words"Our enemies have said they can subdue the country by a proclamation. It is our part to prove them that they are sadly mistaken."

During the summer of 1812 public confidence was probably never lower than on the July day Brock addressed the Assembly. In his emotional opening speech to this extra session of the Legislature, Brock appealled to the Members' pride and patriotism.

"While I address you as legislators, I speak to men who in the day of danger will be ready to assist not only with their counsel but with their arms. By unanimity and dispatch in our counsels and vigour in our operations we may teach the enemy this lesson: that a country defended by free men enthusiastically devoted to the cause of their king and constitution can never be conquered."

The exhortation demonstrated Brock's determination to "speak loud and look big." The impassioned speech was intended also for propaganda purposes, filled as it was with compliments to the loyalty of the militia and the cooperation of the Assembly.

Legislators issued their own vigorous appeal to the populace, charging them to support the war and fight to defend their country. After declaring that the spirit of loyalty and the flame of patriotism were burning from one end of the Canadas to the other, they finished with the following somewhat overblown declaration.

"You fight not for yourselves alone but for the whole world. You are defeating the most formidable conspiracy against civilized man that has ever been contrived, a conspiracy threatening greater barbarism and misery than followed the downfall of the Roman Empire. You have an opportunity of proving your attachment to the parent state that is the last pillar of true liberty and the last refuge of oppressed humanity."

These rousing words must have sounded a little hollow to the hero of Upper Canada for even in the midst of the mayhem the legislature refused Brock's appeal for partial suspension of habeas corpus. Brock wanted worriors not words and on August 4th he wrote, "The House of Assembly have refused to do anything they are required. Everybody considers the fate of the country is settled and is afraid to appear in the least conspicuous in the promotion of measures to retard it." For Brock there was no use knocking at the door. There was rarely a crisis in which hope and peril presented themselves so vividly.

Brock pondered then acted. He believed every problem had a twin called solution and lost little time in plaintive protestations. He prorogued the session, promptly declared martial law on the authority of his king's commission and prepared to face the American forces flooding across the border. Never before or since was the independence of Canada been in greater danger than during that summer of 1812. The emotional allegiance of a number of newly arrived settlers from the United States was in doubt and Brock feared arming militiamen he did not wholly trust. Although there were 11,000 provincial militiamen Brock knew that number included "doubtful characters in the Militia" and he was in full agreement with General Prevost that "it might not be prudent to arm more than 4,000."

American leaders charged that Britain was forcing military service on newly arrived immigrants to their country. Britain was accused by President Madison "of naturalizing thousands of American citizens, but also of compelling them to fight its battles against their native country." Brock knew loyalty could not be legislated and decided to rely only on volunteers who had received special training. Aged eighteen to fifty, these men were drilled six times a month and Brock used them to form two flank companies to fight alongside British regulars.

Brock's efforts in this regard proved successful as reported by the York Gazette on June 6, 1812.

"We are highly gratified to observe that two flank companies composed of smart, active, young men selected from the volunteers of the York Militia Regiment, performed their manoeuvres well, proving the great advantages of the new mode of disciplining the militia adopted by his honour, General Brock. Though drilled but a few times, it shows how soon young men animated by a zeal for honour and defence of their country and prompted by an eagerness to learn can be sufficiently trained fit for effective service." These militiamen served as rallying-points for the more patriotic elements of the population and it was to them that Brock appealled when he issued this General Militia order. "The President, being informed that a number of good rifles are in the possession of some members of the militia, the corps commander is authorized to form a company, not to exceed 30 rank and file men as voluntarily offer their services."

At this critical time in his military and civil leadership, Brock was plunged into a personal family and financial crisis. His steady military promotions had all been acquired by purchase. His brother, William, a senior partner in a London firm of bankers and general merchants, was very interested in his younger brother's military career and had advanced him the cash needed for his commissions. William had intended these advances as gifts to Isaac, however, unbeknown either to him or to Isaac, the amounts were entered on the company's books as loans. When the company suddenly ran into unexpected financial difficulties, the immediate repayment of all loans was demanded. Neither William nor Isaac had the money to repay them. Another brother, Irving, had on advice from William invested heavily and lost all and when he blamed his brother for his losses family discord was added to financial distress. When Brock learned of their falling out he he sought from afar to restore harmony. He urged Irving to forgive William and informed William that he had made arrangements for regular payments from his annual salary of 1000 pounds to be forwarded to help pay off his indebtedness.

In His Own Words"I shall enclose a power of attorney. Do with the money what justice demands, pay as you receive it unless any of the family needs financial assistance. In that case make use of the money and let the worst come." Brock protested that he had received not even "a scrape of a pencil, and pleaded for news that all was well. [*] When Sir John Moore was killed he was replaced by the Duke of Wellington. Moore, a very popular general, had been struck by a cannon ball that crushed his shoulder and left his arm hanging by a piece of skin. The ribs over his heart were broken and stripped of flesh. Despite this it is recorded that he sat upon the field "collected and unrepining" as though he had received no wound whatsoever. "After thanking the surgeons for their trouble he died without a struggle." [**] The Duke of Wellington, known as the Iron Duke, was the greatest British soldier of his time. He achieved this honour fighting Napoleon in Spain in what was called the Peninsular War. Every young officer wished to serve under Wellington and win fame and honours. Brock was envious of these men and their opportunities and he wanted desperately to join them. [***] Ironically this was a knighthood which Brock would never know he had won for he died in his dash up the Heights before word of the honour arrived in Upper Canada.

|

|

|

[*****]Military Glossary

Bastion A projecting part of a fortification, consisting of four sides (two faces and two flanks) allowing the defenders' fire to cover the main walls.

Battery A protected emplacement for artillery, either for besiegers or defenders. The word can also describe a group of cannon or mortors.

Casement A secure, covered chamber built into the walls of a fort and used to shelter personnel and supplies from bombardment. Casements could be pierced to serve as positions for defensive musket and cannon fire.

Embrasure An opening made in a parapet or wall allowing cannon to fire through it while the gunners remain under cover.

Palisade A fence of pointed stakes spaced at roughly six-inch intervals to serve as a barrier while allowing defensive fire to pass through it.

Rampart The main wall of a fortress.

Salient An angle pointing outwards from a fortification.

Sally a sudden attack by the defenders against the trenches and works of the besiegers.

Sap a narrow trench dug to approach a fortress.

Stockade A wall constructed of vertical pickets. Intended here to indicate a wall with no space between the pickets. See palisade.

Works fortifications or the approaches of a besieging army.

Copyright © 2013 Website Administrator