foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

BROCK AT THE OUTBREAK OF WAR, PART 2

History is an account of remarkable events

|

|

Upper Canada - War of 1812 |

Some individuals make their appearance on earth and stand out head and shoulders above all others. Brock was such a person. With his brilliance of vision and imagination he was a priceless asset to the province.

And well he therefore does and well has guessed,

Who in his age has always forward pressed:

And, knowing not where heaven's choice may light,

Girds yet his sword and ready stands to fight

If these be the times then this must be the man.

It was a sombre and for some, an exciting time, for the shadow of war hung over the province. The destiny of Canada was suspended by the thinnest of threads. Risk and resignation were on every side it seemed. While all hope of averting war was not yet lost, many believed the storm was about to break upon the provinces. Caution grew into crisis and crisis into climax. As the provinces slid into the chasm of conflict, the time cried out for courage and fortunately there was a man who matched the peril. Isaac Brock brought to his task a quality woefully in short supply: military leadership that was vigorous, imaginative and professional. With his quick perception of Fortune's wheel, he decided daring was the only course to follow and pinned his colours to the mast. He provided inspired, decisive leadership that motivated the fighting men of the province.[See Below *]

|

|

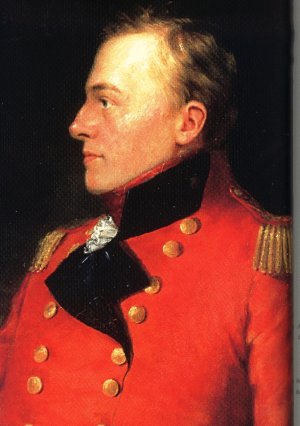

Major General Sir Isaac Brock |

|

|

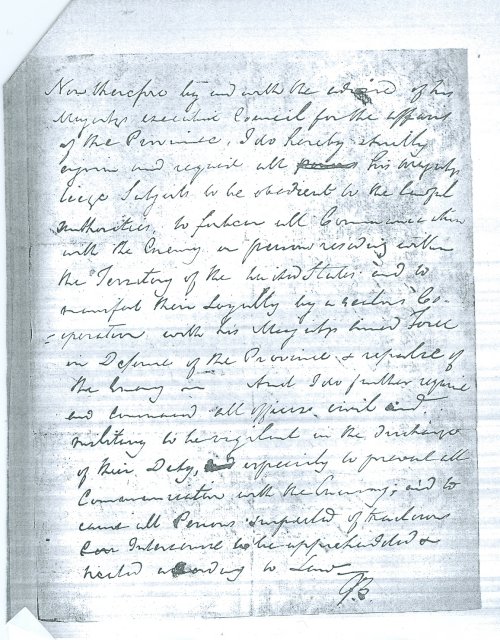

Brock's Handwritten Proclamation |

|

|

Brock's Proclamation |

|

|

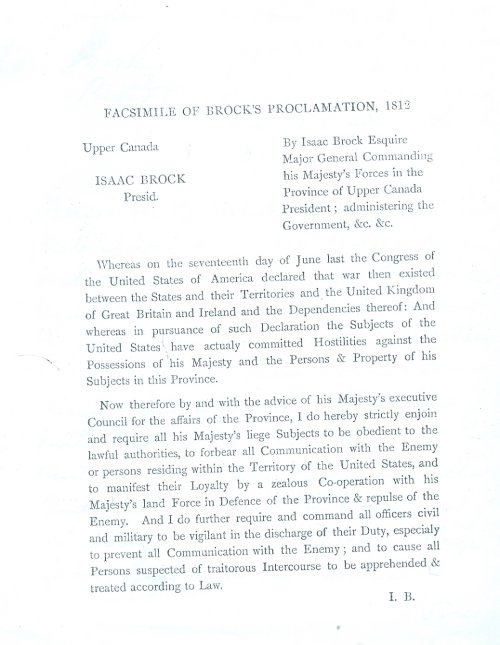

Facsimile of Brock's Proclamation |

The great British Admiral, Lord Nelson, once said, "I am of the opinion that the boldest measures are the safest." Brock shared the same philosophy. Sie vis pacem, para bellum. (If you want peace, be ready for war.) By early 1811, Brock had developed bold, offensive campaign plans for the defence of the province. With rapid, aggressive, successful actions, Brock hoped to revive public confidence in the cause and rouse a surging spirit in thousands of hearts - the vital dynamic in the human story. His plans were good in conception, better in execution and best in results.

Brock knew early victories would impress the Aboriginal tribes, whose alliance in the coming conflict he considered critical. British capture of Fort Michilimackinac accomplished just that, for it greatly impressed the Aboriginal sachems and ensured the support of Natives in the northwest.

|

|

Fort Michilimackinac - Surprised and Surrendered [U.S. National Archives] |

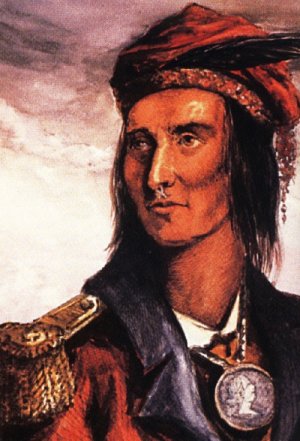

The surrender of the garrison by the Americans was the triumph that triggered northern tribes - Chippaways, Saultes, Winnebagoes, Crees and others to take to the war path for the king. Aboriginal allies were critically important throughout the conflict. Their numbers included the great Shawnee chieftain, Tecumseh - Shooting Star, a fitting soubriquet for the great warrior flashed forth onto the northwest frontier pledging to protect Native territory and traditions. He knew once their land was lost, their freedom would follow.

|

|

"Shooting Star" Tecumseh |

Described by one historian as "the ideal of an Indian chief: stately and commanding yet tense, lithe, observant and always ready to spring,", Tecumseh walked with a limp caused by a wound he received in a previous battle. This skilled and fearless warrior was held in high esteem by friend and foe alike and his impressive nobility and fiery eloquence amazed both British and American officials.

Tecumseh, an heroic ally to Canadians, was respected by Americans as an honourable enemy who fought fiercely to defend his people. However, during a life time lived in the midst of conflict and savagery, he never lost his merciful spirit and deep loathing of cruelty. He preserved throughout that very brutal period a rare humanity and compassion towards his captives. His life stood for "the essential nobility of self-sacrifice and the occasional triumph of the human spirit."

By 1792 Tecumseh had become the acknowledged leader of the Shawnees, a sachem who resolutely opposed every cession of land to the whiteman. The driving force in his life was resistance to the settlers' insatiable urge for ever more land. In 1809 he opposed the American purchase of two and one-half million Aboriginal acres and vowed never to submit to the surrender of their birthright. To fight the loss of land he dedicated himself to building the fragmented First Nations into a Native Confederacy stretching from the Great Lakes to Mexico. Throughout his legendary trips, one of which covered 4800 kilometres in six months, he used his fiery eloquence to persuade Native tribes to join in a common front and his his persistent pressure kept the frontier in a state of agitation.

Realizing that Tecumseh's purpose was to unite the tribes against American encroachment, William Henry Harrison seized the initiative and advanced against an Aboriginal force on November 7th, 1811. Shawnee braves met him at Tippecanoe Creek, Indiana, where they were repulsed with heavy losses on both sides. Harrison burned the Native settlement at Prophetstown, the home on the upper Wabash River of Tecumseh and his brother, the Prophet. At the time of the battle Tecumseh was in the south seeking support for his confederation. This defeat redoubled Tecumseh's determination to fight the Americans. He solemnly vowed not to bury the tomahawk until the Long Knives had been humbled.

The commencement of the War of 1812 saw Tecumseh cast his lot with Great Britain. His warriors would become comrades-in arms with the redcoats. Canadians and Aboriginals faced a common peril and were inspired by a commom purpose. To Canada defeat meant absorption into the United States; to the Red Man it meant expulsion from their homes and hunting-grounds and perhaps the ultimate extinction of their race. Together they would wage war against this insidious threat: the unrestrained expansion of the United States.

In His Own Words"Send them back whence the whites came. Back to the great water whose accursed waves brought them to our shores. War now. War always. War on the living. War on the dead."

In the early 19th century, Canada was compared "to a tree with its tap roots at Halifax, its deciduous branches in Upper Canada and its nourishment flowing across the ocean from Britain." A successful American amphibious assault on Halifax by land and sea forces would have severed Canada's major source of supplies and crippled the country's defence capability. Remaining isolated strongholds could then have been picked off one by one at leisure, or forced to submit for want of supplies. A more feasible land attack on Montreal would have served the same purpose, but it was never seriously considered.

Brigadier General William Hull, governor of Michigan territory, went to Washington with a plan to force the British to abandon Upper Canada by menacing them with an army at Detroit. Success would have meant British ships on Lake Erie would fall into American hands and thus spare the country the cost of building a fleet on the Great Lakes. The prospect of acquiring a vast province and the lakes' fleet with a relatively cheap show-of-force was appealing to President Madison, so he agreed to a Canadian conquest. Raids were to be launched at Detroit and Niagara. Hull, "a short, silver-haired, pleasant, old gentleman, who bore the marks of good eating and drinking," declined to lead the assault, but when pressed by Madison to accept the rank of brigadier general, he reluctanly agreed.

Hull accepted responsibility for the Detroit offensive and was placed in command of Fort Detroit, a square enclosure of about two acres, surrounded by an embankment, a dry ditch and a double row of pickets. Although capable of withstanding a siege, it did not command the river, it had insufficient supplies for a lengthy period and it was two hundred miles from the nearest base of support. On July 9th, Hull received authorization to invade Canada. "Should the force under your command be equal to the enterprise, consistent with the safety of your own post, you will take possession of Malden and extend your conquests as circumstances may justify." In response a hesitant Hull stated: "I do not think the force here equal to the reduction of Amherstburg (Malden) and you must not, therefore, be too sanguine." No one could say Hull hadn't warned them!

Facing Fort Detroit on the frontier at Amherstburg was the small British garrison, Fort Malden, which had been reinforced by militia flank companies of two Essex regiments. They took up a position at Sandwich directly opposite Detroit and as some of them waited and watched the Americans preparing to attack them, they lost their enthusiasm for conflict and scarcely concealed their anxiety to head home. Hull's forces crossed the Detroit River on July 12, 1812 and took peaceful possession of the village of Sandwich. Much to Brock's exasperation, Fort Malden, which was weakly built and weakly held did not resist the crossing.

Hull's chances of success in his early days in Canada were almost assured. Brock had little hope that the British would be able to defend Fort Malden. An American observer recorded in his diary on 23 July that the fort was "very weak" and that "at one leap I could get into the fort." The Canadian militia began to leave it and return to their homes. Within three days half of them had gone and the residents of Amherstburg its imminent capture removed their effects from the village. However, the Americans chose not to assault the British garrison. The two hundred regulars of the 41st Regiment continued to occupy the fort at Amherstburg and the territory around it presenting a constant but very cautious threat to the American flank.

Hull's plan was to proceed to the Thames area and his order of march was as follows: the advance guard of riflemen; the major part of the army in two columns, flanking the baggage and command centre; these columns in turn were flanked by riflemen in open columns, and finally the rear guard of riflemen. An army on the march was a sight to be seen from afar, its serpentine columns snaking across the countryside, occasionally disappearing from view behind a hill. At nightfall the American forces bivouacked within a square breastwork of fallen trees while mounted scouts reconnoitered for several miles in all directions.

Hull encamped at a pleasant expanse of meadowland, serenely certain that the conquest of Canada would result merely from his appearance. He issued a proclamation to the "INHABITANTS OF CANADA" promising to free them from the tyranny of British rule. But just in case there were any contrary Canadians who were counting on that tyrant to aid them in the coming struggle, he reminded them that they were "separated by an immense ocean and an extensive wilderness from Great Britain. The army under my command has invaded your country. To peaceable inhabitants it brings neither danger or difficulty. I come to find enemies, not to make them. Raise not your arms against your brethren. Being children of the same family and heirs to the same Heritage the arrival of an army of Friends must be hailed by you with a cordial welcome. You will be emancipated from Tyranny and oppression and restored to the dignified state of freedom. I come prepared for every contingency and have a force which will look down all opposition."

While Hull's pretentious proclamation was ridiculed at the time, Brock was concerned that

In His Own Words

"The insidious proclamation was having a considerable effect on the minds of the people."

Brock's fears were well-founded for at first it was effective. He reported to General Prevost that "the disaffected militiamen became more audacious and the wavering more intimidated." A number of those living in this part of the province were newly arrived Americans and some three hundred of them immediately sought protection in the American lines. Hull was accompanied by two residents of Upper Canada who were American sympathizers. They later returned to their homes in Upper Canada where they distributed copies of Hull's proclamation and circulated a petition signed by 400 residents requesting Hull when he did invade Canada to provide protection for those refusing to take up arms against the Americans.

In extreme frustration Brock fumed, "What in the name of heaven can be done with such a vile population?" Brock feared this kind of defeatism. Believing disloyalty would spread he ordered one loyal militiaman "to organize a force to overawe the disaffected." A number of the dissidents were quickly identified and within a few days they were imprisoned.[**]

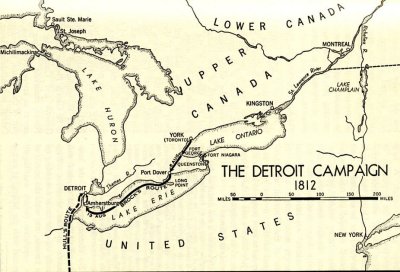

In order to support the small force at Amhersburg in the event that Hull decided to attack it, Brock informed Sir George Prevost on July 29th:"I propose collecting a force for the relief of Amherstburg." On the night of August 5th, the same day he prorogued the Legislature, Brock sailed from York to the head of Lake Ontario on his way to Amherstburg where he expected hot and heavy tidings.

|

|

Capture of the Cayahoga |

Despite having sent his most capable subordinate, Colonel Henry Procter of the 41st Foot, to supercede Lieutenant Colonel St. George as commander at Amherstburg, Brock was still concerned about events in that part of the country. "Unless the enemy be driven from Sandwich it will be impossible to avert much longer the impending ruin of the Country."

Brock expected Amherstburg to be an early loss. "Your Excellency will readily perceive the critical situation in which the reduction of Amherstburg is sure to place me. The militia will not act without a strong Regular force to set them an example. As I must now expect to be seriously threatened from the opposite shore (Niagara), I cannot in prudence make strong detachments, which would not only weaken my line of defence, but in the event of retreat endanger their safety."

Meanwhile Hull was sitting in Sandwich trying to make up his mind what to do, if anything. Hull's chances of success were greatly increased in his early days in Canada. Brock on the other hand had little hope that the British would be able to defend Fort Malden. An American prisoner commented in his diary on 23 July, that the fort was "very weak and that at one leap I could get into the fort." Militiamen had grown tired of waiting and many had begun to leave and return to their homes. Within three days half were gone and the residents of Amherstburg, in anticipation of an American takeover, had removed their effects from the village.

When day after day passed with no attack from Hull, the morale of the defenders began to improve. Hull's hesitation had now turned to panic, based on his fears about the vulnerability of the supply lines, the lack of naval support, the failure of Americans on the Niagara front to help him by attacking, and most of all on news of the fall of Michilimackinac, the key to fur trade west of Lake Michigan.

Brock meanwhile with 300 men - mostly militia with a sprinkling of British regulars - was coming west from Fort George on the Niagara River by forced marches and lake boats. As he did so he endeavoured to arouse the countryside by appealing to Canadian patriotism and by stirring the Indians to greater effort. Brock handled his Indian allies well. He accepted the fact that they could not be expected to act as regulars, that they were motivated largely by self-intestest and had an entirely different concept of war from Europeans. While he found them "fickle and degenerate," he knew all too well the psychological fear their very presence brought to any conflict.

Fortuitously earlier in July, the American schooner, Cuyahoga, was captured by a British patrol. On board they found Hull's personal stores, clothing and most importantly, his official correspondence with details about his forces and their deployment. Brock carefully scrutinized this valuable information before setting out for Amherstburg.

|

|

Sir George Prevost |

Prior to departing for Fort Malden, Brock learned that militiamen in the Norfolk area were reluctant to march to the relief of Amherstburg. Colonel Thomas Talbot, an aide and close friend of John Graves Simcoe, who eventually oversaw the settlement of 28 townships along the north shore of Lake Erie, expressed despair at the "dismal prospect" of war with the United States. His despondency was shared by men who would not march. Talbot documented his inability to raise a detachment of Norfolk militia for service in the Detroit region.[***] In the same letter to Brock, Talbot, who was inclined to be defeatist given the state of the area's defences, hinted at the possible necessity of surrender. In that event he wanted to ensure any surrender terms included his own welfare. "I'm most anxious to know your determination if you should be forced to send for Genl. Hull. (i.e. seek terms) Do let me know as those in promise of land on performing their settlement duties should be included in such condition as may be entered into and something relative to myself."

|

|

Thomas Talbot |

This communication greatly angered Brock. He was shocked and incensed at any thought of yielding to the enemy and "lost all confidence in the gallant Colonel" when Talbot suggested craven capitulation and special protection for Port Talbot. In a letter to Prevost, Brock stated: "My situation is getting each day more critical. The population is worse than I expected and the Magistrates have declined to act. The officers of the Militia exert no authority and everything shows as if a certainty existed of a change taking place soon." The defeatest attitude stemmed from the belief it would not be long before there would be an American takeover. Brock feared the effect this apathetic attitude would have on other residents of Upper Canada.

|

|

Brock's Route to Detroit |

With coolness of judgement, calmness of manner, complete self-reliance and an exact sense of timing, Brock acted to deal with the crisis. With his small forced comprised mostly militia with a sprinkling of British regulars, he sailed from York to Burlington Bay and travelled by forced marches overland to Brant's Ford on the Grand River, where he was successful in securing the allegiance to the British cause of a number of Natives. He travelled on to Culver's Tavern in Norfolk, where he gave an impassioned speech to the reluctant recruits appealling to their Canadian patriotism. He attempted with his speech to disarm the opposition, rally the faithful and placate the uneasy moderates. His ringing words had the desired effect. The Norfolk militia turned out to a man and subsequently were highly praised by Brock. Two of their officers actually received medals. Brock proceeded to Long Point with several officers and a detachment of York and Lincoln volunteers. At Port Dover they they were joined by Colonel Robert Nichol and two flank companies of the Norfolk militia. [****]

|

|

Port Dover |

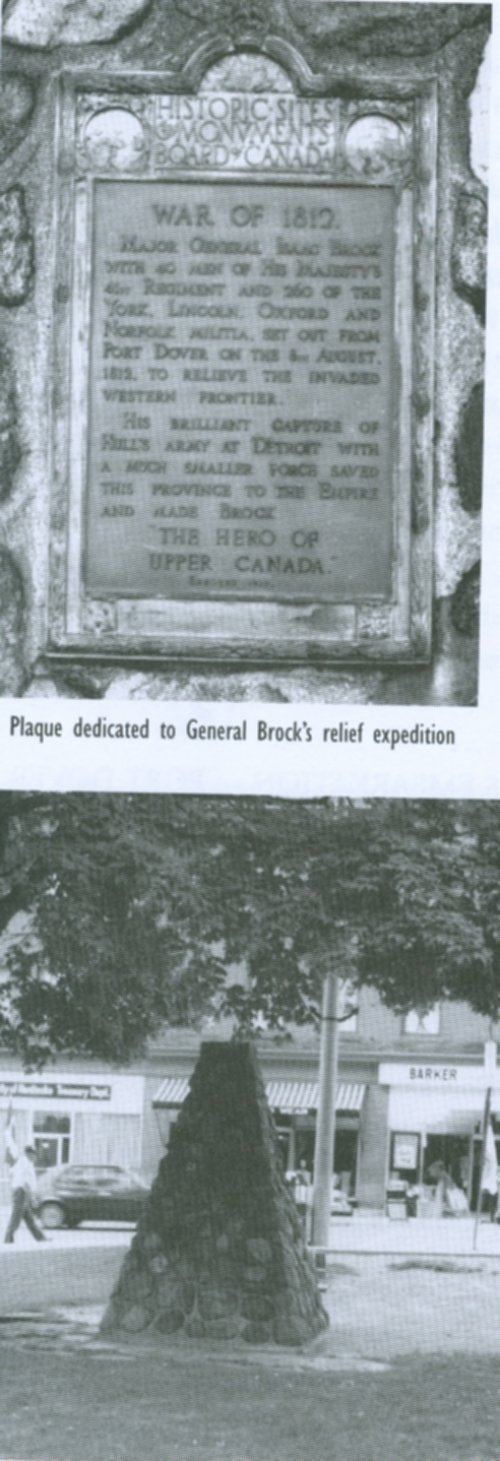

In the city park at Port Dover, a plaque and a cairn commemorate the embarkation site of Brock and his band as they headed for Hull at Amherstburg.

Major General Isaac Brock with 40 men of His Majesty's 41st Regiment and 260 of the York, Lincoln, Oxford and Norfolk militia, set out from Dover on the 6th of August to relieve the invaded western frontier.

His brilliant capture of Hull's army at Detroit with much smaller force, saved this province to the Empire and made

Brock

THE HERO OF UPPER CANADA

|

|

Brock Cairn bearing Plaque at Dover |

On Aug. 8th the fleet of small boats stopped at Port Talbot, where additional recruits were obtained, many through the exertions of a newly inspired Colonel Talbot. Brock proceeded to Port Dover on Lake Erie where in ten, small, decrepit vessels, he embarked his mass of manoeuvre comprising 50 regulars and 260 militia. Many of the latter were chosen for their boating skills and knowledge of the Erie shoreline.

Despite the fact that Hull was within easy striking distance of Amherstburg with the odds four to one in his favour, he chose not to follow his boastful proclamation with forceful action, Instead he sought security in Sandwich (Windsor), where for a month he had wasted valuable time frittering away his forces in different directions. Finally when he heard that British regulars were en route from Niagara to reinforce Fort Malden, he turned tail and retreated to the safer side of the river. Hull dallied despite the rising indignation of his officers. As day after day passed with no attack from Hull, the apprehension which was based less on fact than fear eased and the morale of the defenders began to improve. On 26 of July Colonel Henry Procter who had been sent by Brock to assume command arrived at the fort. By then General Hull had become "the object of jest and ridicule" by the British troops.

With all the speed the heavy weather permitted, Brock and his forces sailed along the Lake Erie shoreline, the ragtag bunch of boats crowded with men and two grasshopper cannons. After five days of frustratingly slow progress in the ramshackle fleet, they reached Amherstburg at midnight on Thursday the 13th of August. Brock was delighted with the endurance displayed by his troops. Militiamen and civilians carrying torches cheered Brock's arrival and as he stepped onto the wharf, 500 Shawanee braves welcoming him with a feu de joie of musketry. Brock mindful of the need for frugality asked a local Indian agent to tell them to save their scanty ammunition for the coming confrontation. Notwithstanding Hull's humilitating retreat across the river and the lateness of the hour, Brock summoned the garrison officers to plan their offensive.

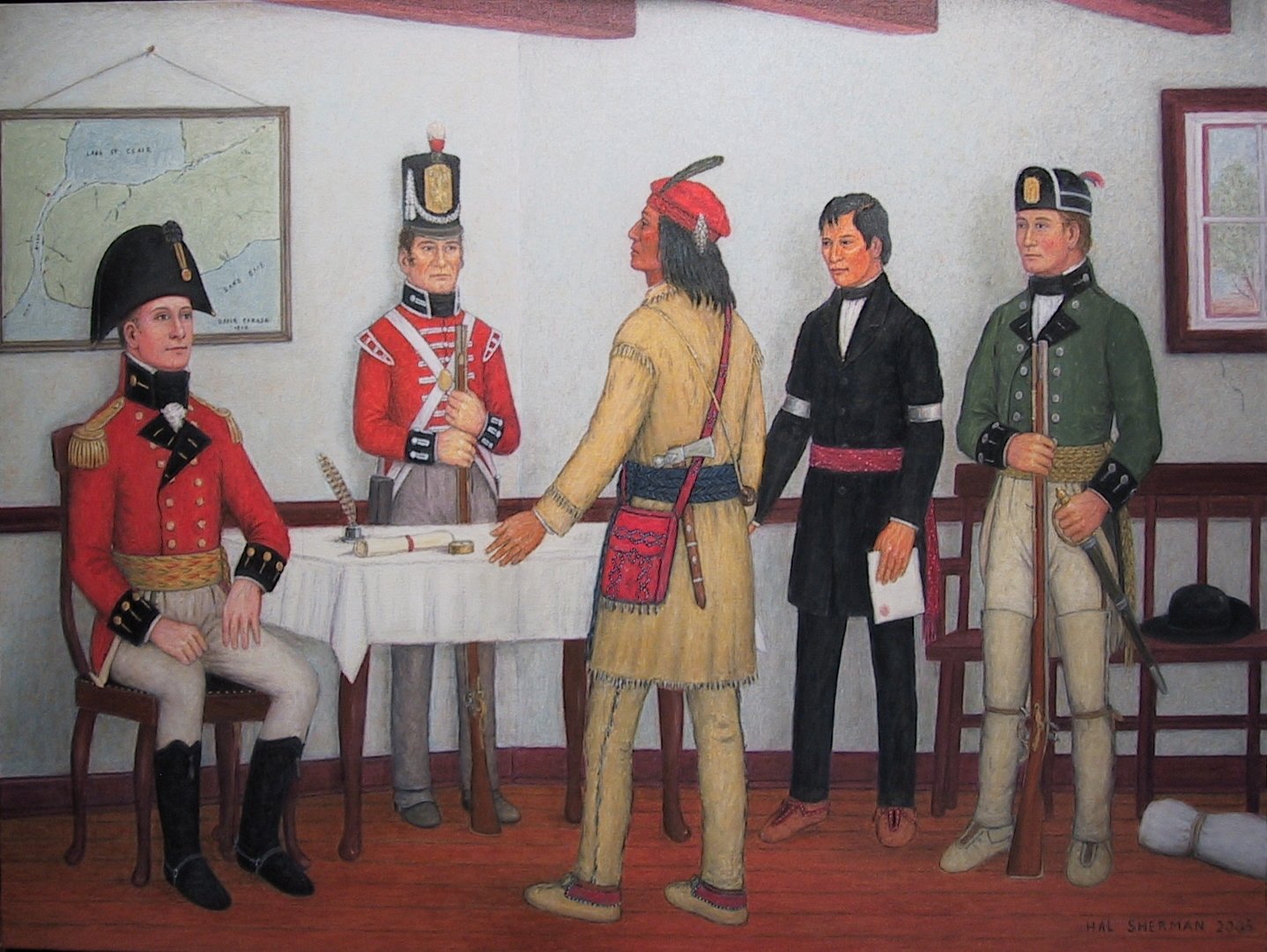

Tecumseh joined the meeting with several other chiefs. He was introduced to Brock who raising his eyes from the papers he was studying, beheld 'the king of the woods' the personification of freedom of the forest. Tecumseh calmly returned the gaze noting Brock's athletic form as it towered to its full height. The auburn-haired, blue-eyed Brock was a massive man and his scarlet coat with gold epaulettes made him appear even bigger. Tecumseh, who was equally tall, wore tanned deerskin. His complexion was the colour of light copper and his bright hazel eyes beamed confidence, energy and optimism. Born to lead the two commanding figures shook hands to seal a firm friendship.

|

|

Brock & Tecumseh Meet |

|

|

Brock,Tecumseh, Billy Caldwell & Commander of the Caldwell Rangers, William Caldwell |

One of Brock's most "invaluable qualities was his willingness to carry the war"to the enemy and he set about implementing part two of his strategic plan: the capture of Fort Detroit. Seeking information about the countryside across the river, Brock turned to Tecumseh and inquired what they would would encounter when they attacked Detroit. Extending a roll of elm bark on the ground with four stones, Tecumseh sketched with his scalping knife a very detailed outline of the landscape - its hills, woods, rivers, roads and morasses. Brock was impressed. Here was a man of some substance.

Recognizing that he was dealing with a superior individual and a very important ally, Brock shrewdly bestowed on Tecumseh the rank of a brigadier-general in the British army. Later in a letter to Lord Liverpool Brock wrote, "Among the Indians at Amherstburg I found some extraordinary characters. He who attracted most my attention was a Shawnee chief, Tecumseh. A more sagacious or gallant warrior does not, I believe, exist. He was the admiration of everyone who conversed with him"

On the fourteenth Brock addressed the assemblage of some 1000 Native warriors and later met with the major chiefs to secure their enthusiastic support for an attack on Fort Detroit. Brock began the offensive with an artillery barrage. He reconnoitred the frontier and on the 15th oversaw the placement of cannons which commenced bombarding Fort Detroit around 4 p.m. Despite the fact that the British were merely "showing their teeth" with their random artillery fire, they began to get the range and the crashing cannonade further dismayed the disheartened Hull. The death-dealing balls were finding their mark. One shell killed four officers. The British kept up their bombardment until nearly midnight.

During the early morning hours Tecumseh and 600 braves crossed to the American side two miles down river. Tecumseh's fiery, indomitable warriors included braves from tribes whose names "throbbed like distant war drums: Shawnee, Miami, Fox, Sac, Ottawa, Wyandot, Chippewa, Potawatomi, Winnebago, Dakota."

|

Brock's intention to attack was not fully supported by all his officers. Several notably Henry Procter advised against crossing the wide river in the face of well-entrenched, well-armed, formidable force. They faced a stronghold of 2000 men securely situated behind 22-foot ramparts and a palisade of 10-foot hardwood spikes all defended by 33 cannons and an 8-foot moat. However, Hull's captured correspondence indicated that American morale was low and their commander discouraged. The Native "bush telegraph" confirmed it was a good time to strike. Brock decided to take a "calculated risk."

In the early morning hours of the 16th Brock led his mobile force across the Detroit River. His "gallant band" comprised 250 regulars of the 41st Regiment, 50 soldiers from the Royal Newfoundland Regiment and 400 Upper Canadian militiamen. Little did they or their leader know they were walking with destiny.

Brock knew that to some extent all warfare was psychological and that performance was everything. His own account of his appreciation of the situation has been preserved.

In His Own Words

"Some say that nothing could have been more desperate than the measure I took, but I answer that the state of the Province admitted of nothing but desperate measures. Confidence in the American General was gone and evident despondency prevailed. I succeeded beyond expectation. I crossed the river contrary to the opinion of my colonels and it is, therefore, no wonder that envy should attribute to good fortune what in justice should be credited to my own discernment. I proceeded from a cool calculation of the pours and contres."

"For what the leaders are that as a rule will the men below them be." Xenophon

Warfare was new to most of the militiamen but the sturdy yeomanry had faith in their leader and their flintlocks at the ready. With racing hearts they waited for the clash to come that historic Sunday. The rising sun's rays shimmered on the buttons and bayonets of the regulars, tantalizing targets in their scarlet tunics, grey trousers, red shakos and various shades of sashes, belts, braids and buttons according to their rank. The regulars, the militia and the few remaining warriors surged across the river just north of what is now Windsor.

|

|

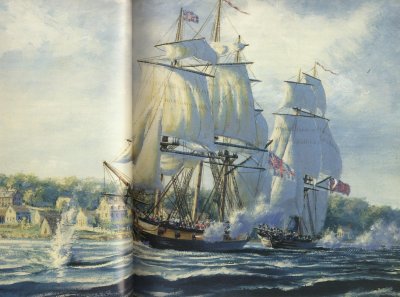

Fort Detroit Bombarded by Queen Charlotte and Hunter |

Their crossing was accompanied by cannon fire from the vessels Hunter and Queen Charlotte and by the hair-raising war whoops of the Aboriginal braves who had crossed earlier. Brock in full dress, tight-fitting scarlet coat with gold lace and buttons, cocked hat, white trousers and glistening black Hessian riding boots. led the way. Tecumseh was quick to notice and later remark upon his imposing presence. "Other chiefs say Go. He says, Come."

Brock was a consumate soldier and wily politician who exploited fear. He knew he had the psychological upper hand so vital in warfare. His foe had a great fear of the Aboriginal warriors and in his ultimatum to the Americans, Brock played on Hull's horror of their fury. In his communication to Hull, he stated matter-of-factly but ominously,"It is far from my inclination to join in a war of extermination, but you must be aware that the numerous body of Indians who have attached themselves to my troops will be beyond my control the moment the contest commences."

Earlier in his proclamation to Upper Canadians, Brigadier General Hull had claimed the war was being waged to liberate Canada.

Inhabitants of Canada.

"The army under my command has invaded your country. To peaceable inhabitants it brings neither danger or difficulty. I come to find enemies, not to make them. Raise not your arms against your brethren. Being children of the same family and heirs to the same Heritage, the arrival of an army of Friends must be hailed by you with a cordial welcome. You will be emancipated from Tyranny and oppression and restored to the dignified state of freedom. I come prepared for every contingency. I have a force which will look down all opposition."

|

|

Brigadier General William Hull |

In war men may lose in a day what they have spent years building up. Hull, who had led a heroic bayonet charge at the Battle of Stony Point back in 1778, was an impressive leader during the Revolutionary War. Now he was a figure whose bombast was not matched by his bravery. His reputation was to be ruined by events about to occur.

Faced also with the havoc caused by heavy cannon fire, the blood-curdling cry of tomahawk-toting warriors and all those regular redcoats firing on the fort, Hull's fighting spirit fled. He drooped when he stood up and sagged when he sat down. Instead of greetings and the warm clasp of friendship Hull had expected from Upper Canadians, he faced the cold steel of Brock's bayonets and the terrible tomahawks of Tecumseh's worriors. Mentally and morally paralyzed by the predicament he faced, Hull became a puppet in the manipulative hands of Isaac Brock.

During times of extreme stress Hull stuffed his mouth with quid after quid of chewing tobacco until its dark drool ran down his beard and onto his chest. Now as spittle spilled out of his mouth he reacted on terrified impulse. Fearing defeat and the awful consequences to civilians including his own daughter and grandchildren huddled within the walls of the fort, Hull capitulated. He saw surrender as the only way of preventing a slaughter and without consulting any of his officers, he sent his son to signal surrender. Hull had overstayed his welcome on the stage of history.

|

According to a popular ballad of the time,

"Those Yankee hearts began to ache,

Their blood it did run cold.

To see us marching forward

So courageous and so bold.

Their general sent a flag to us,

For quarter he did call,

Saying, 'Stay your hand, Brave British boys,

I fear you'll slay us all.'"

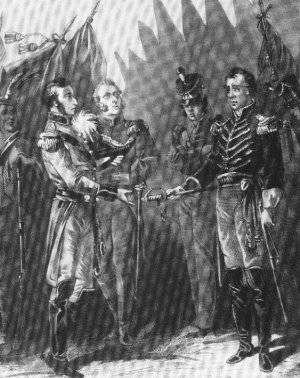

To Brock's stunned disbelief a white flag, a table cloth, was displayed from the walls of the fort. The firing ceased and a few minutes later Captain Hull emerged from the fort with a flag of truce. Brock appointed his provincial aide-de-camp Lieutenant Colonel John Macdonell, the province's attorney general. of whom it was said, "the field, the cabinet, the Forum are all to be the scenes of his renown - his honours rain not upon him, they come in tempests." Accompanying Macdonell was Brock's military aide-de-camp, Major John Bachevoye Glegg. They were "to conclude any arrangement that may lead to prevent the unnecessary effusion of blood." Within an hour they returned with the conditions of the capitulation.

Shortly after noon on Sunday, August 16, 1812, the British entered, lowered the American flag. A salute was fired from one of the captured brass cannon that bore the following inscription: "TAKEN AT SARATOGA ON THE 17TH OF OCTOBER, 1777." When the British officers first it they were delighted and greeted the old captive cannon with kisses. The inscription be amended by adding: "RETAKEN AT DETROIT AUGUST 16, 1812" The band played God Save the King and hoisted the Union Jack. After an absence of sixteen years, the British flag flew once again over Detroit. Using a combination of bluff and blackmail Brock with a tiny attacking force had captured an American army of 2,500, some thirty-three cannon, four hundred rounds of 24-pound shot, one hundred thousand cartridges, 2500 rifles and bayonets, umpteen barrels of gunpowder, a number of horses and a newly built 16-gun brig Adams.

|

|

"Hull Hands Sword to Brock |

The victory parade held the next morning in front of the fort included a march past of militiamen, redcoats and the invaluable Native worriors. Major General Brock took the salute in full military dress of scarlet-and-gold mounted on his great charger, Alfred. He was accompanied by his officers in full dress uniform. Brock used the occasion to recognize Tecumseh. In a typically instinctive gesture Brock removed his richly tasseled scarlet sash and fastened it about Tecumseh in the presence of the troops and Aboriginal warriors. In addition he gave Tecumseh a brace of silver-mounted pistols in token of his admiration. In return the great Shawnee chief slipped the arrow-patterned Native sash from around his waist and presented it to Brock. Their friendship forged in the fire of war, the two esteemed allies for just five short days, were soon to be united by a hero's death.

The next morning Brock noticed that Tecumseh was not wearing the sash and inquired why. Tecumseh responded, "I have given to it Round Head of the Wyandots, who is older and more valiant than I." Round Head was a prominent warrior at Detroit and remained a valiant ally until his death. Two months later when Brock was felled by a bullet to the breast he was wearing Tecumseh's sash.[*****]

|

|

Major General, British Army |

In his message to General Prevost Brock wrote, "When I detail my good fortune, Your Excellency will be astonished." Tecumseh too was amazed at their bloodless victory and congratulated Brock on his triumph over the Long Knives.

In His Own Words

"The Americans endeavoured to give us a mean opinion of British generals but we have been witness to your valour. We observed you from a distance standing the whole time in an erect position and when the boats reached shore you were the first man on land. Your bold and sudden movements frightened the enemy and so compelled them to capitulate to half their number."

Brock issued a proclamation to the inhabitants of Michigan assuring them of protection to life, property and religious observances. Then having made arrangements for the civil and military occupation of the Territory, he left Colonel Procter in command of the garrison of two hundred and fifty men in Detroit and hastened back to York.

News of the surrender of Fort Detroit rocked the United States, which had in the words of one writer, "been basking in the valor of ignorance." A furious President Madison described it thus in his message to Congress. "Brigadier-General Hull was charged with this provisional service, having under his command a body of troops composed of regulars and of volunteers from the State of Ohio. Having reached his destination after his knowledge of the war and possessing discretionary authority to act offensively, he passed into the neighbouring territory of the enemy with a prospect of easy and victorious progress. The expedition, nevertheless, terminated unfortunately, not only in retreat to the town and fort of Detroit but in the surrender of both and of the gallant corps commanded by that officer. The causes of this painful reverse will be investigated by a military tribunal." Dolly, Madison's wife, railed at this weak-kneed warrior."Do you not tremble with resentment at this treacherous act?" American historians called the surrender of Fort Detroit the most humiliating capitulation in their country's history. The War Hawks of Washington could hardly believe the news. Public outrage greeted news of the abject defeat of a major military force without firing a shot.

The New York Post reflected this fury in an editorial dated August 31st, 1812. "On the disgraceful and deplorable results of our first military efforts in Canada, we are not in a temper to say much. The whole plan of the campaign was miserably imbecile and utterly inefficient, yet such a catastrophe as is just announced was beyond our most gloomy apprehensions. It appears we must be utterly unequal to cope with the experienced veteran British officers in Canada." Another newspaper editor raged: "A recent event has fired the soul of every lover of his country at the disgraceful evacuation of Detroit. Every circumstance that we have yet heard of marks villainy and treason in its strongest colours. What would induce General Hull and the General Officers to evacuate Detroit God only knows"

An American prisoner, Surgeon's Mate James Reynolds, kept a journal of the days he was imprisoned following the British capture of Detroit. "August 16th - Sunday. Pleasant weather but unpleasant news. We heard about noon that Hull had given up Detroit and the whole Territory of Michigan. The Indians began to return about sunset well mounted and some with horses and chains. Who can express the feelings of a person who knows that Hull had men enough to have this place three times and gave up his post. Shame to him, shame to his country, shame to the world. When Hull first came to Detroit the 4th U. S. Regt. would have taken Fort Malden and he with his great generalship has lost about 200 men and his Territory. Can he be forgiven when he had command of an army of about 2500 men besides the Regulars and Militia of his Territory and given up to about 400 regular troops and Militia and about 700 Indians.

August 17th - Monday. Cloudy. The news of yesterday was confirmed. The Indians were riding our horses and hollowing and shouting."

General Hull and fellow-prisoners reached For George on the 26th of August. Later they were conveyed to Quebec in parties, some going in vessels of war from Niagara to York to Kingston. Others were transported in small boats along the shore and across the Carrying Place by the Bay of Quinte. Most were confined in hulks in the St. Lawrence at Quebec where they remained until they were exchanged. One observer present when Hull alighted from his carriage recorded that the general looked "quite corpulent and appeared hale and in high spirits." Canadians looked on in awe and astonishment as Hull and his 582 regulars were marched through the streets of Montreal. Once the surrender was accomplished, Hull emerged from his catatonic state much like a man coming out of anaesthetic. Scarcely able to speak or act during the conflict, he now became both loquacious and lucid.

In His Own Words"I have done as my conscience directed. I have saved Detroit and the Territory from the horrors of death and destruction."

In 1814 Hull was charged with treason. The specifications under this charge were: (1.) "Hiring the vessel to transport his sick men and baggage from Miami to Detroit; (2) Not attacking the enemy's fort at Malden and retreating to Detroit; (3) Not strengthening the fort of Detroit and surrendering." Hull was also charged with cowardice, neglect of duty and unofficer-like conduct. The specifications under the charge of cowardice were: "(1) Not attacking Malden and retreating to Detroit; (2) Appearances of alarm during the cannonade; (3) Appearances of alarm on the day of surrender; (4) Surrendering of Detroit." The court martial decided he would not be tried for treason.

At his court martial Hull elaborated on the mournful state of the militia under his command. Regarding the reference by one officer to the tears of the troops when Hull surrendered, Hull cynically said they were obviously not from the Michigan militia "because part of them deserted and the rest were disposed to go over to the enemy rather than fight him." Perhaps, he said, it was the Ohio volunteers "who mutinied in the camp at Urbana and would not march until they were compelled to do so by the regular troops." Or perhaps it was those who refused to cross into Canada and at Brownstown under Major Van Horne, "ran away at the first fire and left their officers to be massacred." Hull concluded that with such troops and with officers who were "in hostility to me and even conspired against me what was I to expect from a contest?"

After a session of eighty days the court decided hull was guilty of cowardice and neglect of duty and unofficer-like conduct. He was sentenced to be shot dead and his name struck from the rolls. The court recommended mercy "because of his revolutionary service and advanced age" The sentence passed on 25th of April, 1814 was: "The rolls of the army are to be no longer disgraced by having upon them th name of Brigadier General Willaim Hull." The death sentence was remitted by the president and Hull spent the remainder of his days attempting to prove his innocence. He died in relative poverty.

Brock's small force was the knife's edge that opened the oyster. The incredible accomplishment of Brock and his little band from a colony of 500,000 people had resulted in the deception and capitulation of a major fort of a "nation of seventeen states, six territories and 7.5 million people." Why did the large lose and the tiny triumph? The answer was mainly because of Brock and British preparation which saw Canada superior in leadership and logistics. The man and the moment came together. In a subsequent message to Prevost Brock proudly reported that not one life was lost after the fort had surrendered. Prevost was highly impressed and congratulated Brock on his "singular judgment, firmness, skill and courage." Prize money was promised to the young men who had participated in the raid, but it was very slow in coming and was still not paid to them by 1817.

News of the victory was carried throughout Upper Canada in dispatches by express riders thundering along the dusty roads on the fastest horses they could find. Riders could cover 100 miles then another rider took over. When word of the rout reached York on August 20th, the tiny capital erupted in celebration. When General Brock returned to York he was received in triumph. He never anticipated the outpouring of affection and esteem his success earned him that Sunday, August 16th, 1812. Only as addresses of welcome and letters of congratulation poured in from around the province did the true significance of his triumph at Detroit dawn upon him. With this totally unexpected victory Brock had made good his foothold in history. He was regarded as the savior of the province.

In the short space of 19 days he had met the Legislature, arranged public affairs of the province, travelled about three hundred miles to confront the invader and returned the possessor of that invader's whole army and a vast territory about equal to the size of Upper Canada.

The astounding news made front page headlines.GLORIOUS NEWS!!!

"Dispatches have just now arrived from General Brock dated August 17th, 1812, stating that he took possession of that important post {Detroit} on the 16th without the sacrifice of a drop of British blood. Every individual, together with their General, was animated with the most glorious spirit. Upwards of 2,500 Troops have surrendered prisoners of War, and about 25 pieces of Ordnance have been taken. Thus it hath pleased Providence to crown his Majesty's Arms with an early and important victory." Their future was unknowable, but at least this victory gave them hope.

All of Canada was ecstatic. "The inhabitants were thrown into a frenzy of delight by the almost incredible intelligence that Detroit had been taken along with the entire American army." The news brought the country to its feet. The jubilation of the people of the province knew no bounds at this bloodless victory. Canadians could scarcely believe the news even after it became well known. An American officer exclaimed, " This event has animated Canada beyond anything you can conceive." The victory stirred the passions of the people like nothing else could have. Brock's victory had burst the bubble of American supremacy. The success at Detroit caused newly arrived Americans in Upper Canada, who fully expected the American army to advance in victory processions throughout the province, to reconsider their loyalty. Any support that existed in Upper Canada for the United States quickly melted away. Even hitherto doubtful residents now openly committed themselves to the British cause, a commitment they found hard to renounce "in the darker days ahead."

Canadian exuberance and bravado at the event are reflected in the following ballad dating from this period.

THE BOLD CANADIAN

Come all ye bold Canadians,

I'd have you lend an ear

Unto a short ditty

Which will your spirits cheer

Concerning an engagement

We had at Detroit town,

The pride of those Yankee boys

So bravely we took down.

Those Yankees did invade us,

To kill and to destroy,

And to distress our country,

Our peace for to annoy.

Our countrymen were filled

With sorrow, grief and woe,

To think that they should fall

By such an unnatural foe.

At length our brave commander,

Sir Isaac Brock by name,

Took shipping at Niagara,

And unto York he came.

Says he, ye valiant heroes,

Will ye go along with me

To fight those proud Yankees

In the west of Canada?

Our General sent a flag to them

And thus to them did say:

"Surrender up your garrison,

"Or I'll fire on you this day."

Those Yankee hearts began to ache

Their blood it did run cold

To see us marching forward

So courageous and so bold.

Their general sent a flag to us,

For quarter he did call,

Saying, "Stay your hand, brave British boys,

"I fear you'll slay us all.

Our town, it is at your command,

Our garrison likewise."

They brought their arms and grounded them

Right down before our eyes.

Now prisoners we made them,

On board a ship they went,

And from the town of Sandwich

Unto Quebec were sent.

Brock was quick to perceive, shrewd to anticipate, prompt in decision and daring in execution, Born with the qualities which constitute a great commander, he was well aware of the widespread defeatism that existed in the province and knew that

In His Own Words"the state of the province admitted to nothing but desperate remedies."

The easy conquest of Michilimackinac and the bloodless triumph at Detroit of Brock's little band of regulars, militiamen and Natives "awed the disloyal, reconciled the wavering and animated the masses." Brock's audacity and military capability determined the destiny of Canada. Psychologically the victory at Detroit saved Upper Canada. With this totally unexpected triumph Brock had made good his foothold in history. His elevation to the status of hero of Upper Canada awaited him at Queenston.

In a letter to his brothers dated September 3rd, Brock remarked in shocked surprise,

In His Own Words

"They say the value of the articles taken at Detroit will amount to 30 or 40 thousand pounds. My portion will be something considerable. Should the affair (Detroit victory) be viewed in England in the light it is here, I cannot fail of meeting reward. The militia have been inspired by the recent success with confidence - the disaffected are silenced."

On Brock's return to Fort Erie on the schooner Chippawa, a near calamity occurred when the small trading schooner drifted because of fog into waters near Buffalo instead of Fort Erie. When Brock, who was resting below deck, was informed he dashed onto the deck and angrily confronted the master of the vessel."You scoundrel, you have betrayed me. Let one shot be fired from the American shore and I will run you up on the instant to that yard arm." It is not clear why Brock berated the master since he was innocent of any ill intent. Perhaps it was nerves. He was after all a man before he became a monument. In any case the mishap was managed in time and the vessel towed back to Fort Erie.

En route Brock's vessel had met another schooner which conveyed the disappointing and very frustrating news that Prevost had negotiated a ceasefire with the U.S. General Henry Dearborn, the sixty-one year old ponderous general known by is men as Granny, who was in charge of invading Canada. Brock was stunned and angered for he knew the Americans would seize this opportunity to better prepare their forces while the British looked on in frustration.

Resourceful, daring, brave - Brock became the idol of the hour both in Canada and in Britain. General Brock's dispatches and the colours of the United States 4th Regiment reached London on the 6th of October. When news of his Detroit victory arrived, church bells pealed, feu de joie filled the air and bonfires burned throughout the night. Not infrequently history indulges in a touch of irony and by one of those superb coincidences in which it abounds, that very day was Brock's forty-third birthday. On that same day back at Fort George, "that most lonesome place," Brock observed his birthday alone in the solitary watches of the night, forlornly describing his 43rd birthday as "the gloomiest ever."

In London on the 13th of October Irving Brock received a short note from Isaac written at Detroit shortly after the Detroit victory."Rejoice at my good fortune and join me in prayers to heaven." Ironically, on that very same day, perhaps, even at the very same hour at place called Queenston Heights, Brock fell mortally wounded. Although he died a relatively young man Brock made the myth [******]on which names and nations are created.

Brock was one of those fascinatiing figures upon whom a period of history pivots. His campaigns had been brief but immortal. The numbers were small but their handling skilled and the stakes immense. Even later American victories at sea could not compare with them. Michilimackinac in July; Detroit in August; Queenston in October - these were his titles to fame and glory and to the everlasting gratitude of Canadians. Thus began the legend.

The Montreal Gazette hailed the victories of the illustrious, little band of heroes for "the undaunted courage they displayed in so nobly defending this devoted portion of the British Empire." Detachments of the 41st and 49th regiments "had covered themselves with glory." The Provincial Militia and their Indian allies "appear to have been convinced that the fate of the day depended upon their individual exertion and consequently every man became a hero." The same writer lauded Brock as "that being whose arm was strength and who had thus been pleased to interpose his protecting shield during these arduous and important conflicts," and he bemoaned the death of "our illustrious Chief who so nobly fell on that glorious day."

The day following Brock's death John Beverley Robinson, a leading light in York, declared that Brock was "the general who led our little army to victory, whose soul was wrapped up in our prosperity and whose every energy was directed to the defence of our country." No one doubted his words. Even American President Madison remarked on the gravity of Brock's death in his report on the defeat to the Senate and House of Representatives.

In His Own Words

"At a recent attack made on a post of the enemy near Niagara by a detachment of regular and other forces, the Americans troops were forced to yield to reinforcements of British regulars and Indians. Our loss has been considerable and is deeply to be lamented. That of the enemy will be the more felt, however, as it includes among the killed the commanding general who was also the governor of the province."

In a report dated October 13th, 1812 General Sheaffe informed General Prevost of the "American attack in force at Queenston" and its consequences.

In His Own Words

This brilliant success is clouded by the ever-to-be lamented death of Major General Brock. The zeal, ability and valor with which he served his King and country render this a public loss that must long be deplored and his memory will live in the hearts and affections of those who had the opportunity of being acquainted with his private worth."

News of Brock's death was conveyed to his brother, Mr. William Brock, by Brock's other aide-de-camp. In the sad, dark hours of the night he sat alone recording the circumstances of the death of a dear friend, his commanding officer.

"Major J. B. Glegg

Fort George, Upper Canada,

14th Oct. 1812

"My Dear Sir:

With a heart agonized with the most painful sorrow, I am compelled by duty and affection to announce to you the death of my most valuable and ever to be lamented friend, your brother, Major General Brock.

He fell yesterday morning at an early hour, when at the head of a small body of regular troops, consisting of the flank companies of the 49th Regiment, disputing every inch of ground with a very superior body of the enemy's troops in the town of Queenston. The ball entered his right breast and passed through on his left side. His sufferings I am happy to add were of very short duration and were terminated in a few minutes when he uttered in a feeble voice: "My fall must not be noticed or impede my brave companions from advancing to victory." [*******]

His lifeless corpse was immediately conveyed into a house at Queenston, unperceived by the enemy, and although we were obliged by overwhelming numbers, to leave it there for some hours, it was not observed by the enemy, and upon victory declaring our favour, I hastened to the spot and finding my lamented friend in the same concealed place where we had left if in the morning, the body was immediately conveyed to Fort George, where it now lies in state in the Government House and has already been bedewed by the tears of many affectionate friends. His loss at any time would have been great to his relations and friends, but at this moment I consider the melancholy event as a public calamity. He was beloved and esteemed by all who had the happiness to know him, and was adored by his army and by the inhabitants of this province.

Signed: Major J. B. Glegg,

Aide de Camp

Although the war was to last for another two years, the worst danger for Upper Canada passed in 1812. When military numbers were few and morale at an all-time low, the Americans failed to find a way to take advantage of their great opportunity to conquer Canada. Their failure was due to their own unpreparedness and the fact that they sadly lacked leadership. The Mother country ensured that Canada was better prepared for war. The forces were tiny but in the circumstances they were enough. A small naval force controlled the lakes. There was a modest but efficient body of regular troops and there were trained officers capable of skillful and energetic leadership as exemplied by Isaac Brock.

Maintenance of Morale The principles of war as currently defined were well illustrated in the important campaigns. The importance of morale cannot be over-emphized. "High morale is a pearl of very great price and the surest way to obtain it is by success in battle." [Field Marshal Lord Bernard Montgomery]

Offensive Action Brock saw the importance of seizing the offensive in spite of the odds.

Concentration of Force and Economy of Effort While Brock's forces were limited he concentrated all the force he had the means to move. He also had superior moral force.

Flexibility British naval superiority made it possible to rapidly move limited forces along the long frontier and this contributed greatly to the saving of Upper Canada in this campaign.

[*] It is said that some great generals owe their fame more to their accidental position than to qualities of greatness. They are like the Dutch boy whose finger plugged the hole in the dike because he happened to be there! On the other hand a really great person is epoch-making by the decisions he makes and the direction he gives the forces at his disposal His will even his whim makes a profound difference in history.

[**] In what is known as the Ancaster Bloody Assize, a treason trial of 19 Canadian settlers who supported the Americans during the war was held in June 1814. Four were aquitted, one pleaded guilty and fourteen were found guilty. When the death penalty was pronounced on June 21st, petitions poured in on behalf of the accussed men. Faced with the duty of deciding on the fate of the fifteen the Executive Council, the three judges and the Attorney General, granted reprieves to seven and eight suffered "the execution of the awful sentence of the law." A rude gallows was prepared with eight nooses on Burlington Heights. On July 20th, 1814, five days before the Battle of Lundy's Lane, the victims were placed in two wagons, four in each and drawn under the gallows. After the nooses were placed around their necks, the wagons were withdrawn leaving the unfortunate traitors to dangle and slowly strangle to death."

[***]Colonel Thomas Talbot's inability to convince residents to ride had a good deal to do with his own personal unpopularity with the settlers for he wielded despotic powers as the government's chief representative in the area. At a later date and under other leadership they gave good service.

[****]'Erie, Pennsylvania Apologizes 200 Years Later' Almost 200 years after American soldiers looted and burned the tiny Lake Erie settlement of Dover Mills during the War of 1812, Norfolk County has received an apology from its neighbours to the south. The tongue-in-cheek apology was delivered earlier this month at a luncheon held in conjunction with a heritage festival with an 1812 theme in Erie, Pa. Ian Bell, curator of the Port Dover Harbour Museum and musician, was performing in the festival and received the public apology on the country's behalf. Speaking to Norfolk council at Tuesday's meeting Bell reported on the event and displayed a plaque of "eternal friendship" and a wooden bowl presented by Erie officials to make amends. Councillors chuckled as Bell displayed apology cards made by Erie school children bearing messages like, "Sorry for burning your town." Bell also received six Erie coffee mugs to make up for the silver and china looted in the 1814 raid. "They were probably nicer than what we lost," Bell noted. In return he presented the Erie mayor with a gift - a six-pack of Molson Canadian beer. Mayor Rita Kalmbach who lives in Port Dover near the site of Dover Mills, said Norfolk residents don't hold a grudge. "Apology accepted," Kalmback said.

[*****]This story has been questioned but the presence of an 'arrow' sash among the general's uniforms received by his family appears to provide proof of its validity.

[******]In his book The Science of History, the author Dr. Mark Buchanan says mere greatness for historical figures is not enough; they have to be at the right place at the right time when "criticality" is vital. The word 'criticality' describes a situation which is teetering on the brink of instability and at that critical moment the action of the historical figure takes place "on the heap of human affairs." Buchanan compares it to adding one more grain to a heap of grain thereby triggering a dramatic change - the collapse of the heap of grain.

[*******] Information regarding the last words of dying heroes is frequently conflicting; other reports indicated that Brock died without uttering a word. A volunteer with the Light Company of the 49th Regiment who was near Brock when he fell ran up to him and asked, "Are you much hurt, Sir?" Brock placed his hand on his breast and made no reply.

[********] Globe and Mail 11 September, 2008

"For the better part of two centuries, Sir Isaac Brock has been dubbed "the Hero of Canada," but a pair of impressive artifacts connected to the famed general appear to be headed south of the border for lack of a Canadian buyer.The treasures in question are a 57-centimetre carved wooden war club, believed by some experts to have been given to Brock by famous Shawnee leader Tecumseh after the duo led the capture of Detroit in the War of 1812, as well as stunningly painted knighthood papers awarded to Brock just before his death. The artifacts come with tantalizing stories. After Brock died, his brother Savary returned the club - and it is believed, the knighthood papers as well - to the Channel Island of Guernsey, the major-general's birthplace. (Brock never learned about his knighthood, as he died just three days after the honour was awarded in Britain..) They were passed down through generations, and were among personal effects that were buried in a large metal truck on the family estate during the Second World War, so they would not be taken by Nazi occupiers. The last Brock descendant to own them was Nicholas Mellish, Brock's great-nephew six generations removed, who sold them to Jamieson, who was acquainted with the family, last year. Jamieson acknowledges the history of the war club is uncertain, and doubts about its provenance have scared away a series of potential Canadian buyers. The strongest claims to the Tecumseh link are rooted in circumstantial evidence attested to by experts such as Dr. Ted Brasser, a respected consultant and former curator of tribal art at the Natural Museum of Man (since renamed the Canadian Museum of Civilization). Brasser told the Globe there is little doubt the club belonged to Brock and that "all historical references fit together and make [Tecumseh's role] a believable story." In a report he wrote for Jamieson, Brasser states that the curved end of the club is characteristic of those from Michigan and Wisconsin between 1770 and 1800; the scalloped edges suggest Great Lakes Region woodwork and the patterns carved into it are reminiscent of those found on woven goods from the Great Lakes and Shawnee. "What else could [Tecumseh] give [Brock] as a gift? There's nothing else that would be important. But without being there, you can't prove it," Jamieson said.

In January, 2007, the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa had the first opportunity to buy the club directly from Mellish, who thought it could accompany one of its more striking possessions: the red coat Brock was wearing when he was killed at the Battle of Queenston Heights in October, 1812, bullet hole prominent on the breast. But collections manager John Corneil said the War Museum declined because the documentation simply didn't add up. Jamieson was next in line and he quickly bought the club (and several months later, the knighthood papers). Since then, he has offered to sell the club to the War Museum once more, the Museum of Civilization, the Art Gallery of Ontario, the Royal Ontario Museum and the Glenbow Museum in Calgary, as well as to Brock University. The latter three were later offered the knighthood papers as well. The knighthood papers, which boast exquisite hand-painted crests and seals, suffer from no such authenticity doubts, but have failed to arouse the same interest as the club. Brasser said he is not surprised that no Canadian institution has stepped forward, but is nonetheless disappointed to see the war club departing so soon after returning to Canada. "General Brock played an important role in Canadian history. It would be another embarrassment for Canada to let that go."

Copyright © 2013 Website Administrator