foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

FORT GEORGE & GUEST

History deals with our lives as social beings.

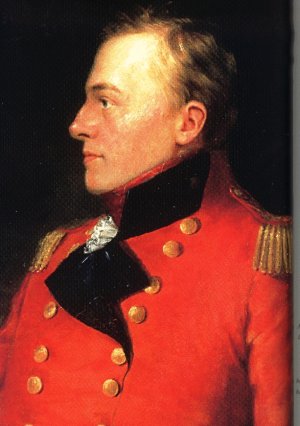

"It is a most lonesome place," wrote Isaac Brock to his brothers of life at Fort George, the little army base buried in the wilderness of Upper Canada. He informed his brother, Irving

In His Own Word"You who have passed all your days in the bustle of London, can scarcely conceive the uninteresting and insipid life I am doomed to lead in this retirement."

|

|

Lieutenant Colonel Isaac Brock |

The winter of 1804 was particularly long and dreary. The river had frozen over and the countryside round about was layered in deep snow. Visitors were few and far between and but for his books, Brock would have despaired of the desolation of life at Fort George, particularly after the culture, camaraderie, food and fine wine he had enjoyed when garrisoned at Montreal and Quebec City.

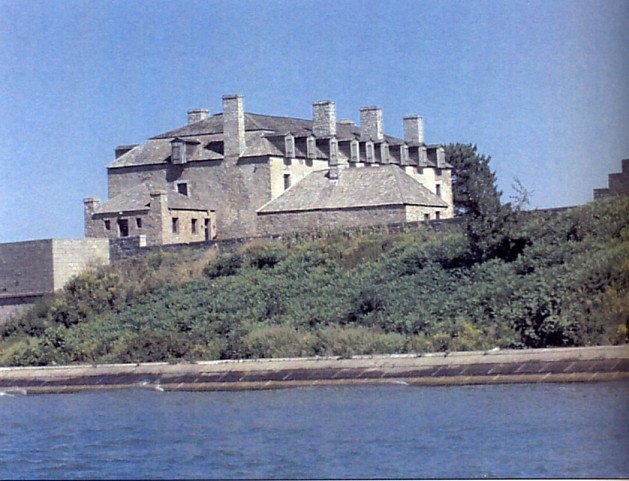

When Fort Niagara was relinguished to the United States in August 1796,

|

|

Fort Niagara from the Niagara River |

the garrison, guns, stores and British flag were removed to Fort George which Governor Simcoe had ordered constructed in May 1794.

|

|

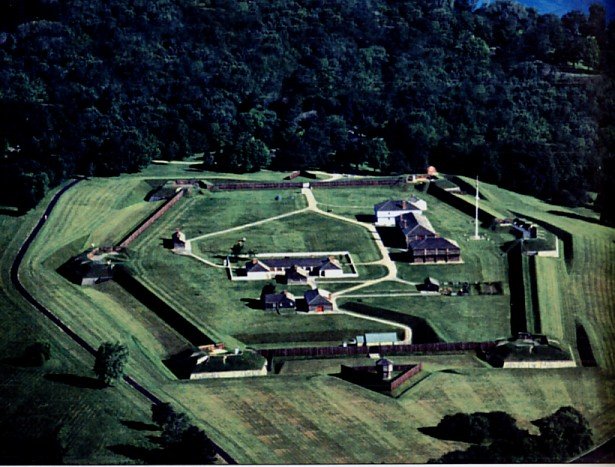

Fort George |

The sketch of the fort he ordered built was an irregular triangle with the river-front a simple palisade.

|

|

Fort George from the Air |

It was located behind Butler's Barracks so as to "command Fort Niagara."

|

|

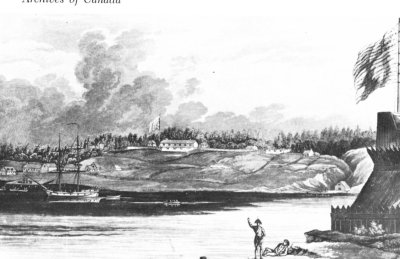

Fort George from Fort Niagara |

The fort was not far from Niagara, the town whch had been renamed Newark by Simcoe. However, by an act of the Legislature in 1798 the village resumed its former name of Niagara.

Some critics suggest the location chosen for the fort was not a good site for the fort would command neither the entrance to the river nor protect the town which with a population of one hundred and fifty homes was the most important settlement in Western Canada. A French expert on fortresses declared that the chief requirements in fortification were simplicity and strength. Fort George was built to satisfy both. The fort, headquarters in Upper Canada of the British army, was located on the west bank of the river about a mile from where it merged with the waters of Lake Ontario. Named after King George III, Fort George [See Below *] was constructed in fits and starts over the next decade.

|

|

Fort George |

By 1803 it was a low, square fort with six earthen and log bastions, one located at each of its four corners ( the top left known as Brock's Bastion) with one at the centre of each of the longer sides. Bastions are four-sided defensive structures projecting from the main rampart of the fort. They permitted defenders to fire along the face of the main rampart. All were within earthen ramparts and a cedar palisade 12 feet high encircled by a dry, shallow ditch. The stockade is loopholed for musketry. For several hundred yards on all sides trees and undergrowth had been cut to open a field of fire for fort's cannons.

The fort was defended by batteries of forty-eight guns of different sizes ranging from three-pounders to 18-pounders. The 3-pounders or "grasshoppers" were easily transported using a two-wheeled wagon called a 'limber' pulled by a team of horses and driven by artillymen who sat on boxes containing supplies for the gun. Six-pound field guns were used by both sides. With a charge of almost three pounds of black powder, the gun could fire a six pound iron shot about 1250 metres. Rounds of grape shot or cannister were effective at a rang of 300 metres. By 1812 the fort's guns included two heavy 24-pounders, the biggest then available.

|

|

Three-pounder (left)

& Six-pounder |

Within the palisade the Royal Engineers had constructed four defensible barrack buildings or troop blockhouses, two storeys high of thick, squared logs, containing a guardhouse, a kitchen, messes for the men and a spacious building for the officers' quarters, 37 metres by 6 metres with wings 6 metres by 6 metres. There was also an octagonal blockhouse for stores and a hospital with dimensions 21 metres by 8 metres.

A stone magazine was constructed with an arched roof for powder storage. Unlike the magazine at York which was devasted by a violent explosion when the Americans attacked the tiny capital in April 1813, this magazine survived an American assault and is the only building to remain intact from the time of the war. It survived a similar fate to York's solely because of the daring bravery of a handful of men. On the morning of the 13th of October, Fort George was under a heavy artillery barrage of red hot shot from Fort Niagara with disastrous effect. Within a few minutes the jail and court house in Queenston were ablaze along with some fifteen other buildings including the roof of magazine containing eight hundred barrels of powder. Without an instant's hesitation a few men led by Major Thomas Evans and Captain H.M. Vigoureux of the Royal Engineers climbed upon the burning building and frantically extinguished with pailfuls of water before extracting the hot shot embedded in the burning timbers.

|

|

Original & Restored Magazine at Fort George |

Meanwhile the guns of Fort George continued their bombardment of Fort Niagara and within a short time the American cannonade was silenced by the explosive power of British mortor and howitzer shells. A howizter fired a shell at a higher angle than could a cannon. Unlike the cannon ball, the shell was not solid but filled with black powder with a measured wooden fuse that ignited when the mortor was fired. It exploded over the heads of the enemy shearing them with jagged metal fragments flying in all directions. A mortor, which functioned in the same manner, hurled an exploding shell in a high, arching trajectory, a heavy mortor being able to throw a shell more than two thousand metres.

|

|

Howitzer (left) & Mortor |

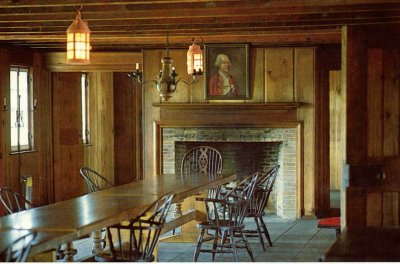

An officer was a gentleman in the social cast of the time and expected to live like one. While the officers' quarters were crude, they were comfortable. The long mess table was covered with a white linen cloth on which was placed good china, crystal glasses and regimental plate that sparkled in the flickering candlelight. The scarlet and the glitter of brass contrasted with the white-coated waiters, as they hovered behind the officers' chairs, passing the port decanter from right to left around the table as the sovereign's health was drunk and toasts were proposed. Then the officers sat back, relaxed and lit cigars, the blue smoke from which wafted slowly up into the rough-hewn rafters.

|

|

Officers' Mess, Fort George |

Wherever an important traveller came to British North America, he eventually ended up at the fort in the glitter and the glamour of the garrison. This was certainly true in 1804, a year destined to be different at Fort George. Shortly after Brock assumed command, a celebrated guest arrived at the isolated outpost. It was the renowned Irish national poet, Thomas Moore. Moore had cut short his tenure as the Admiralty's registrar in Bermuda and prior to returning to Britain had embarked on a tour of several places in the United States and Canada.

|

|

Thomas Moore |

returning to Britain had embarked on a tour of several places in the United States and Canada.

|

|

Thomas Moore's House, Kegworth, Ireland |

With his Irish melodies, which included The Last Rose of Summer, Believe Me If All Those Endearing Young Charms, and The Harp That Once Through Tara's Halls, Moore had established himself as the national bard of Ireland. He was also a skilful writer of nostalgic, patriotic songs which he set to Irish tunes. One reviewer said Moore's work reflected "the moods and miseries of one person," while another referred to "the playful and elegant fancy" of Moore. A third said "The fancies of Moore are exquisitely beautiful." Moore's fame spread to the new world where many were captivated by the man and his music. He conquered hearts wherever he sang for his enraptured hosts including the American President Thomas Jefferson who invited Moore to the White House.

Moore spent a delightful fortnight at Niagara where he was heartily welcomed at Fort George by Lieutenant Colonel Isaac Brock, the officers of the 49th and the members of Upper Canada's social register. His stay at Niagara was restful and very enjoyable. Various diversions were laid on for celebrated guest, one of the most impressive was a gathering of Tuscarora warriors under Chief Brant at the Indian encampment on the Grand River. Moore in one of his celebrated epistles wrote, "The Mohawks received us in all their ancient costumes. The young men ran races for our amusement and gave an exhibition game of ball while the old men and women sat in groups under the surrounding forest of trees. The scene altogether was as beautiful as it was new to me."

At that time a majestic, spreading oak tree stood about two miles from the town on the Queenston Road. From a plot of grass under it, one had a wonderful view of the Niagara River as it swept round an immense curve with fair fields on one side and on the other magnificent forest giants in the background. Moore with a poet's eye for beauty sometimes sat and mused under the tree and it acquired the name Moore's Oak. A ballad he composed there contained these lines:

I knew by the smoke that so gracefully curled

Above the green elms, that a cottage was near,

And I said if there's peace to be found in the world,

A heart that is humble might hope for it here.

Moore found his fame had preceded him to Canada. At Niagara a watchmaker refused to charge him for repairs, and a ship's captain declined any payment, an absolute requirement from all other passengers. The governor of Lower Canada even delayed a ship's departure, so that Moore would not have to rush through the dinner he was attending in his honour and hurry to board. Moore was the celebrated guest of the governor of Nova Scotia, and wherever he went his way was smoothed and he was smothered by admiring and attentive guests.

Moore was royally entertained during his stay at Fort George, and he paid for his hospitality at the piano, where he played and sang well into the wee hours of the morning. His visit to the Falls of Niagara was a highlight. As he beheld nature's power and beauty, he seemed preoccupied and one reporter suggested that his mind was not engaged with the view. On the contrary, Moore declared, he was enthralled by the beauty of the sight and the sound of the great cataract. In fact, he commemorated it in a poem which he wrote shortly after leaving Fort George.

From the banks of the St. Lawrence River, Moore dedicated the new melody to one of his many lady friends, Lady Charlotte Rawdon.

"Oft when hoar frost and silvery flakes

melt along the ruffled lakes;

When the gray moose sheds his horns,

When the track, at evening, warns

Weary hunters of the way

To the wigwam's sheering ray,

Then, aloft through freezing air,

With the snowbird soft and fair

As the fleece that Heaven flings

O'er his little pearly wings,

Light above the rocks I play.

Where Niagara's starry spray,

Frozen on the cliff, appears

Like a giant's starting tears.

There, amid the island sedge,

Just upon the cataract's edge,

Where the foot of living man

Never trod since time began,

Lone I sit, at close of day;

While, beneath the golden ray,

Icy columns gleam below

Feathered round with falling snow,

And an arch of glory springs

Brilliant as the chain of rings

Round the neck of ladies hung,

Ladies who have wondered young

O'er the waters of the West

To the land where spirits rest."

During his time at Fort George, Moore shared many happy hours with Brock and the other officers. "To Colonel Brock in command of the fort I am particularly indebted for his many kindnesses during the fortnight I remained with him." Moore wrote of the pleasant moments he had spent in their presence.

"Whom, known and lov'd through many a social eve,

'Twas bliss to live with and 'twas pain to leave."

Moore dedicated to Canada, his poem Canadian Boat Song

"Faintly as tolls the evening chime,

Our voices keep tune and our oars keep time;

Soon as the woods on the shore look dim,

We'll sing at St. Ann's our parting hymn;

Row, brothers, row, the stream runs fast,

The rapids are near and the daylight past."

In Moore's poem, Oft, In The Stilly Night, he recalled the treasured times of his travels.

"Oft in the stilly night,

Ere Slumber's chain has bound me,

Fond memory brings the light

Of other days around me."

Among those blissful days Moore said he particularly cherished the time he had spent and the treatment he had received while in Canada, which he described as "the very nectar of life."

[*]. Military GlossaryBastion: A projecting part of a fortification, consisting of four sides (two faces and two flanks) allowing the defenders' fire to cover the main walls.

Battery: A protected emplacement for artillery, either for besiegers or defenders. The word can also describe a group of cannon or mortors.

Casement: A secure, covered chamber built into the walls of a fort and used to shelter personnel and supplies from bombardment. Casements could be pierced to serve as positions for defensive musket and cannon fire.

Embrasure: An opening made in a parapet or wall allowing cannon to fire through it while the gunners remain under cover.

Palisade: A fence of pointed stakes spaced at roughly six-inch intervals to serve as a barrier while allowing defensive fire to pass through it.

Rampart: The main wall of a fortress.

Salient: An angle pointing outwards from a fortification.

Sally: a sudden attack by the defenders against the trenches and works of the besiegers.

Sap: a narrow trench dug to approach a fortress.

Stockade: A wall constructed of vertical pickets forming a wall with no space between the pickets as in a palisade.

Works: fortifications or the approaches of a besieging army.

Copyright © 2013 Website Administrator