foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

BRADDOCK'S DEBACLE

Wit is capable of striking down a whole regiment of regulars.

The conflict that convulsed this continent known as the Seven Years' War, which Americans call the French Indian War,] marked a turning point in British history. It was the final bout between Britain and France in North America. Their drawing of swords resulted in the Great War for the Empire, which changed the course of history. It was called by Sir Winston Churchill, the first world war. This clash of empires occurred across the continents of Asia, Europe and America.

In North America, France and Britain allied with Native American tribes, fought each other in a series of terrifying raids and bloody battles. In the beginning, the war with battles and skirmishes being won or lost by each side. Ultimately, however, France had to foresake its American empire, when Wolfe defeated Montcalm on the Plains of Abraham in 1759. This victory led to the creation of Canada and set the Americans on the road to rebellion.

With the disappearance of the French as a force to be reckoned with, the Americans no longer needed British forces to free them from the threat of French attack. They gradually began to believe they could function quite well without British involvement and interference in their affairs. They even foresaw their future dominion over all of the North American continent resulting in what Thomas Jefferson termed, "an empire of liberty." Later others called it "manifest destiny." Control of the continent would require breaking the shackles that bound them to Britain's economic and military might, a consquence of which would be war. But who would rally the rebels?

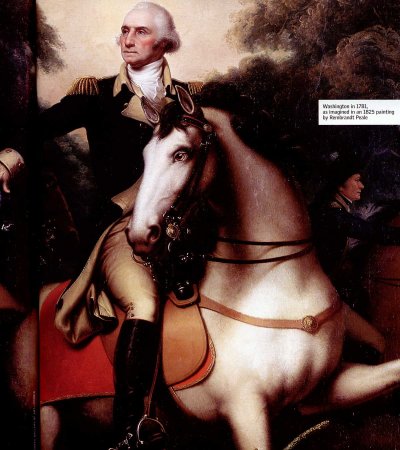

The conflict between Britain and France for the future of North America, provided miltary training for a number of colonial officers, one of whom was George Washington. As a young man of 22, Washington wrote to his brother that he was anxious "to push my career in the Military way." In 1755 his military aspirations appeared to be furthered when he was chosen to serve under Major General Edward Braddock, Commander-in-chief of a combined force of redcoats and colonial militiamen mandated to remove the French from the Ohio country.

But we are getting ahead of our story. The cold war began to grow hot, when news of French activity in North America was ill received in London. The friction that ignited this fight resulted from Britain's increasing concern about France's territorial ambitions on the northern and western borders of its American colonies. Was Louis XV trying to play the role of Louis XIV? Were the French violating the Treaty of Utrecht, which opened the Iroquois country, the basin of the Great Lakes, to Britain's American provinces? France felt threatened too. Louis XV was equally concerned about Britain's "spirit of general domination to extend in the two worlds."

|

|

Louis XV |

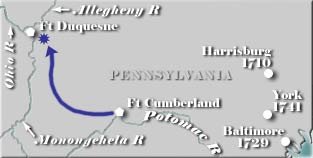

The focus of British and French friction was ownership of the alluring expanse of land beyond the Pennsylvanian frontier - the Ohio River Valley country. This two hundred thousand square miles of valuable hunting and agricultural land led to lengthy conflict to control it. The valley extended over major sections of the present states of Indiana, Ohio, Kentucky and West Virginia. The melding of the Allegheny and Monongalhela rivers produce the Ohio river, which begins in Pittsburg and ends at Cairo, Illinois, from where it flows into the Mississippi river. By the late 1740s, land speculators from the British colony of Virginia and fur-traders from Pennsylvania had begun to move into the Ohio Valley, the interior territory both the British and the French claimed, but neither occcupied.

Nature abhors a vacuum and so did the French. In 1753 Governor Duquesne of New France decided on a bold stroke. New France, dependant as it was on the fur trade as its main resource, needed ever more land and to secure this decided to construct forts at important sites along rivers and lakes. Determined to add this fertile land to their colonial holdings, Duquesne dispatched two thousand men to build a chain of strategic forts along the portage route that connected Lake Erie with the headwaters of the Ohio River thus sealing off the the Ohio Valley from the pestiferous Pennsylvanians. The posts included Fort Presqu'isle on Lake Erie, Fort Le Boeuf on French Creek, Fort Venango where the French Creek emptied into the Allegheny River and Fort Duquesne at the Forks of the Ohio. Impressed by this show of strength, the Indian nations began to turn to the French and sever their trade connections with the Anglo-Americans. The chain of fortifications posed a challenge that Britain had to confront or lose the Ohio Valley and with it the whole interior. Indeed, the fate of all North America was at stake.

Britain bristled at this for the area in question was of great interest to the American colonies along the coast, especially Virginia. To counter the erosion of the Anglo-American position, Major George Washington was dispatched with an escort of seven men and a letter from Governor Robert Dinwiddie of Virginia protesting the French invasion of lands claimed by Great Britain and demanding their immediate withdrawal. In his letter to the French commandant, Dinwiddie wrote that he hoped they would receive George Washington "with the candor and politeness natural to your nation and return him with an answer suitable to my wishes for a long and lasting peace between us." The commandant at Fort Le Boeuf, Jacques Legardeur de Saint-Pierre, described by Washington as "an elderly gentleman with much the air of a Soldier," received Washington politely, but contemptuously rejected his blustering ultimatum. He informed Washington "that it was their Absolute design to take possession of the Ohio and by Heavens they would."

The English colonies were strung along the Atlantic seaboard and represented a some two million people, but they were rarely united. Rivalries were intense, communication was difficult and they paid little heed to British hopes they would present a united force to the French threat. Military might was costly and high taxes were no where to be seen on the colonies' lists of priorities. Despite the disparity in population, French forces were more powerful in North America and while fewer than fifty-five thousand Frenchmen opposed more than two million Americans, the Canadians were more united.

French fort-building forays into the western wilderness represented to the colonists in Virginia and Pennsylvania a foreign invasion of the vast Ohio hinterland that held their destiny. When the French began to build Fort Duquesne, Governor Dinwiddie of Virginia believed they had to protect the claims of the 'Ohio Company' as the Virginia venture was named so he decided to act. The portals to the American west would not be surrendered without a fight.

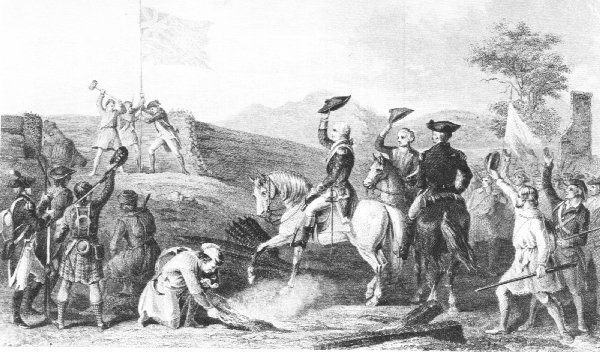

To forestall French occupation of the Ohio country, Dinwiddie dispatched George Washington, a brash young officer perpetually complaining about his pay, along with a motely collection of militia and Indians. This band of a hundred and fifty fighters unexpectedly encountered a small French force led by Ensign Joseph Coulon de Villiers de Jumonville. De Coulon de Villiers, whose purpose was to make peaceful contact with Washington, advanced to invite a parley. His intent was unknown to Washington, who ignited an international powderkeg by firing on the French party killing a number including Coulon. The remainder were captured by the Indians. Washington's blunder was equated to "shooting an ambassador." One Frenchman escaped to tell the tale of what was called a cowardly, unprovoked slaughter. The encounter was the clash that commenced the contest for a continent.

Within a few months of what Washington believed had been a great victory, a vengeance-driven French force led by Coulon's brother confronted Washington's entrenched troops at Fort Necessity., This "small palisaded fort" was a circular stockade made of seven-foot-high upright logs covered with bark and built around a hut containing ammunition and provisions. The ensuing battle on July 3rd, marked the start of the last war between the English, French and Natives in America.

According to Fort Necessity's defenders, Coulon de Villiers subjected them to "outrage and violence." During the confrontation, which lasted nine hours, a withering fire was poured on Washington's warriors by the French troops and Native braves among whom may have been Pontiac. "They kept up a constant falling fire upon us from every little rising, tree, stump, stone and bush." The fierce assault resulted in the death of some 100 men or a quarter of the American military. By nightfall the French had exhausted themselves, their powder and ball, so Coulon called on Washington to parley. He gratefully agreed.

|

|

Treaty at Fort Necessity |

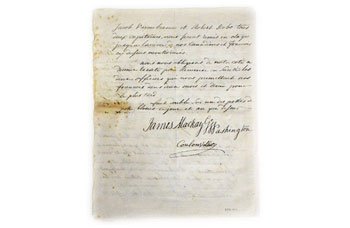

On 4 July 1754 Washington accepted Coulon's demand for the surrender of Fort Necessity. The irony of that date would become clear twenty-two years later. Washington duly signed the French articles of capitulation drawn up by Coulon. The document written in French, [*] which Washington was forced to accept, contained "humiliating and insulting terms of capitulation." By signing it, the future president unknowingly accepted responsibility for the "assassination" of a Canadian soldier.

|

|

Document of Surrender of Colonel George Washington to French at Fort Necessity 3 July 1754 |

Three copies were made, all written in French.

Following this fiasco in the forest, the Americans were permitted to depart with all the honours of war and with drums beating and flags flying, they returned post haste to the safety of their country. Their departure was, in fact, so precipitous that Washington in his haste left his journal behind with abandoned baggage. The contents of the journal were used by the French to brand the English throughout Europe as a perfidious bunch.

Thus in an "isolated mountain ravine on the western slope of the Alleghenies." began the Great War for Empire. Like a contagion it lept across oceans, consumed continents and finished forever the dreams of France for an illustrious future in the New World.

|

|

George Washington |

A chastened Washington ruefully admitted, "I went out and was soundly beaten." His military career appeared to be botched before it began. Expecting the worst, a worried Washington reported on his defeat but instead of being faulted for his failure to defeat the French, he was hailed as a hero who had done the best he could with what he had. More military might was needed to expel the French from the forests of the Ohio country and the governor of Virginia looked to Mother England to provide the men and materiel.

Dinwiddie informed London that they had "acted with all possible Precaution in this affair, but we are now in a state of war begun very unjustly by the French forces." Many among the London merchants opposed an expensive war to capture more trees, while others including Lord Cumberland and the hawks wanted to send an army to "expel the French neck and crop."

Word of Washington's defeat motivated England to act. At a cabinet meeting in London on 29 June 1754, the Duke of Newcastle intoned the 'Imperial' position. "The first point we have laid down is that the Colonists must not be abandoned. Our rights and possessions in North America must be maintained and the French obliged to desist from their hostile attempt to dispossess us."

War fever gripped North America. Everyone was girding for combat and since few had ever been in a battle before, it was a stimulating time. Britain and France made elaborate pretences of peace, while both prepared for war. The French feverishly built warships and assembled troops on the frontier, some of whom along with Canadians were sent to reinforce Fort Duquesne. In response to this growing French menace, the British Cabinet decided to dispatch some military might to America.

Major General Edward Braddock was chosen to lead the redcoated regulars. Braddock's superiors in London scanned the maps and talked of his triumphal trek through a string of French forts on the Great Lakes and the ultimate seizure French Canada. No one knew about the mountains, marshes, rivers, trails and tribes within the terrain through which he was to march. British regulars were good soldiers, but they were untrained for the fighting they would face in North America. One of Braddock's regulars later recalled that, "the very face of the country is enough to strike a Damp in the most resolute of mind. I cannot conceive how war can be made in such a country."

|

|

George II |

Edward Braddock had been a member of his father's fabled regiment, the Coldstream Guards which he joined in 1710. He worked his way up through the ranks by loyal service rather than by purchase which was then the custom. He gained the favour of the Duke of Cumberland, George II's younger son, who was commander of the British army. He promoted Baddock to major general and selected him to settle once and for all, France's aggression on Britain's American frontier before she lost all North America.

|

|

Duke of Cumberland |

Braddock, who was sixty years of age, was a short, burly, fearless, bull-headed-type general. A ruddy-faced, determined, dauntless, disciplinarian, he tolerated no opposition from his inferiors. He was "desperate in his fortune, brutal in his behaviour and obstinate in his sentiments but intrepid and courageous." Crude and overbearing, Braddock was described by one of his detractors who knew the Six Nations and their ferocity when fighting, "a very Iroquois in his disposition."

|

|

Edward Braddock |

|

|

Tobias Smollett |

Tobias Smollett, an English novelist and historian with an unrivalled talent for delineating characters, described Braddock as, "a man of courage and expert in all the punctilios of review, having been brought up in the English guards. Naturally very haughty, positive and difficult of access, he was a man whose qualities were ill-suited to the people amongst whom he was to command." Smollett knew his man for these were the very qualities that contributed to Braddock's downfall and death.

The general himself had few illusions. He had served as governor of Gibraltar and hoped to cap his undistinguished military career with a sinecure appointment as royal governor anywhere. He was less than pleased to have to go to the New World wilderness in order to win his way in the world, but since no other offer was forthcoming he took up the task reluctantly.

Just before Braddock left England, he spoke with an actress friend who recorded his comments. "Producing a map the general told me he would see me no more. He was going with a handful of men to conquer a whole nation and to do this they must cut their way through unknown woods. 'We are sent like sacrifices to the altar.'" Although stubborn and stolid Braddock faced his fate undaunted. His 45 years of service endowed him with a deep-rooted understanding of warfare reinforced by his own experiences. He accepted as truth that the more disciplined and well-drilled force would normally emerge victorious.

On December 22, 1754 HMS Norwich and HMS Centurian slipped their moorings at Spithead and tacked west to Virginia. Braddock, who was aboard the Norwich, had flexible orders: drive the Canadians and the French regulars from their encroachments in Ohio; take Fort Niagara; seize Crown Point and destroy Fort Beausejour. Braddock was dispatched to Virginia along with two rather weak regiments numbering some eight hundred soldiers. As commander-in-chief of a combined force of colonial and regular units, Braddock headed the mightiest force up to then ever assembled in America.

It was hoped this could be done secretly, but unknown to Braddock a copy of his orders which had been secured by bribery, was forwarded to Paris and then to Canada. Braddock's task was to force the few French out of the Ohio Valley before their trickle became a flood. France responded by dispatching forces to Canada and Louisbourg to meet and defeat the threat.

Braddock with the 44th and 48th Regiments containing four hundred men each, as well as 2000 muskets for American militia to support his regulars and 10,000 pounds, arrived in Virginia in February 1755. Promises of participation by colonials made by Colonial Governors had led the English government to expect whole-hearted Colonial co-operation. Braddock expected all would be in readiness. He found instead that matters were badly bungled and bitterly complained of "supiness and unreasonable economy."

Little had been done to prepare for the fight with the French. However, despite their unpreparedness, Braddock's forces were wildly welcomed by the Colonials. While unwilling to pay taxes to the king or take proper measures to protect themselves, the colonials were overjoyed to see the redcoated regiments and their distinguished officer. Braddock's mere presence was expected to frighten off the French and eliminate that pesky, persistent source of danger. Surely a single volley from the sovereign's soldiers would suffice to send the French packing back to the confines of Canada.

Braddock's ill-fated expedition began and ended in debacle. He was appalled by Pennsylvania's lack of preparedness and despite the fighting fever that gripped the colonies, virtually nothing had been done to gird for battle. Braddock had assumed a road would have been cut through the wilderness, but not a tree had fallen. There were no magazines and storehouses and "the jealousy of the people and the disunion of many colonies are such that I almost despair of succeeding." Everywhere he met with apathy and indifference. He was the author of his own misfortune, for it was hard for Americans to rally round a leader whose sneering description of their militia as being made up of "the greatest part Virginians, very indifferent men, this country affording no better." Besides they had responded to the call before only to discover it had all been for naught. In 1745 an American force participated in the capture of the French fortress of Louisbourg following which Britain returned it to the French in exchange for Madras in India.

Braddock sent a blistering letter to the Governor censuring Pennsylvania's parliament for its failure to approve the necessary funding for the militia forces. Ostensibly the colonies were to pay for the troops, but the Ministry conceded this would not likely happen, so Braddock was given secret instructions to forward his bills to the paymaster in London. True to form the colonies found a variety of ways to dodge their debts and responsibilities and the bills were sent home.

Braddock quickly learned about the realities of politics in America. Normally he issued orders and saw them obeyed. He learned that life in the colonies was different. Bickering, prevarication and petty jealousies were the norm and obedience to any order was rare. Money promised never came. Wagons and teams to pull them never appeared. Provisions if they did arrive were late and always less than promised. Braddock received only a mere tenth of the 2500 horses and two hundred wagons he required. The only positive action was the building of a new fortification named Fort Cumberland at the mouth of a place called Will's Creek, but it was some distance from there to the French bastion, Fort Duquesne. An angry Braddock bellowed, "Were it my decision I would disband the army and stand back to enjoy the squeals of the colonial sheep when the French wolves descend upon them. It is only what they deserve."

George Washington joined Braddock at Frederick, Maryland. As commander in chief, Braddock had the King's authority to grant royal commissions, but only up to the rank of captain. Washington, who badly wanted to be a colonel, refused a captaincy as being beneath his dignity, resigned in a huff and returned to Mount Vernon. Braddock needed Washington's knowledge of the country to be crossed and he devised a clever way around the question of rank. His aide informed Washington that "General Braddock will be very glad of your company in his family by which all inconveniences of that sort, that is, rank restrictions, will be obviated." Braddock's solution: give Washington a place albeit unofficial on his staff as colonel. A molified Washington returned to Frederick to join his new 'family.'

|

|

George Washington |

|

|

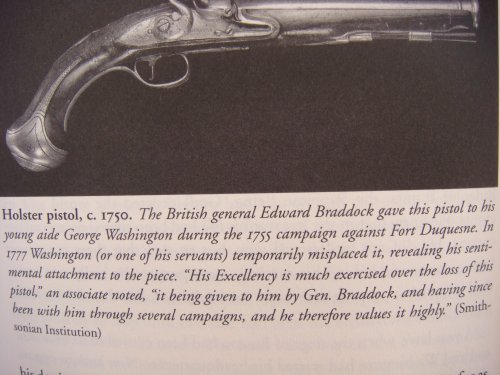

Braddock's Gift of Gun to George Washington |

Provisioned for a quick victory, they prepared to depart from Fort Cumberland at the extreme western point of Maryland for Fort Duquesne at the forks of the Ohio River.

|

|

Major General Edward Braddock |

The British force included the best of the blue-coated Virginians, British regulars and a powerful artillery train. With Braddock and his general's guard were his two aides-de-camp, George Washington and Robert Orme. Washington, who was ill with dysentry and painful hemorrhoids, sat atop a pillow on his saddle to soften somewhat the painful pounding of the ride. With drums rolling and bugles blaring the expedition started off in spit and polish parade ground formation. Discipline was everything to Braddock who saw no further than the tactics he'd been taught: discipline, fire power, simultaneous volleys and unquestioning abedience to bellowed orders. Braddock's troops had nothing to fear from "naked Indians or Canadians in their shirts"

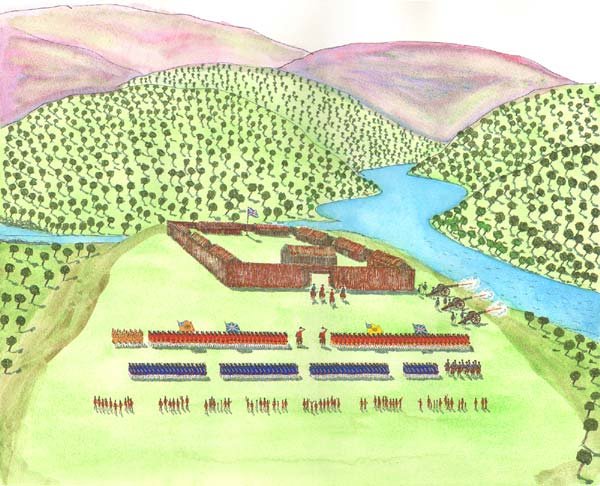

While no citadel, Fort Duquesne was a sturdy little fortress. Located strategically in the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers, the fort had two sides protected by the melding rivers and two by ditches and embankments. Ramparts were constructed of squared logs and backfilled with earth ten feet thick. Four bastions containing a kitchen, blacksmith shop, powder storeroom and prison protected the corners. Firepower included various 3-pound swivel guns and 6-pound cannons.

With over a dozen 18-pounder cannons, cattle and wagons that had been hurriedly collected by Benjamin Franklin, an important member of the Pennsyvania Assembly, the impressive column of 1300 men that included colonials and regualrs almost a mile in length were led by engineers, road builders and 300 axemen to hack their way through the Alleghenies. They marched in traditional linear fashion: four columns wide - two columns on foot in the centre flanked by a column of cavalry on either side. Missing from the mix was a key ingredient: Indian allies.

His mission was inherently madness and he sealed his fate by haranguing the chiefs that their historic claims to the Ohio Valley were worthless. He pompously pronounced that his troops needed no savages to assist them with their task. This prompting persuaded most of them to side with the French.

|

|

Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) |

Braddock knew all about drilling troops in garrison and waging war in the arenas of Europe, but nothing at all about the savage battlefields of the American interior. As a result the impressive legion lacked little but leadership. This view was confirmed by William Shirley, a young American serving as Braddock's secretary, who lmented in a letter to the governor of Pennsylvania, "We have a general judiciously chosen for being disqualified for the service he is employed in in almost every respect. It is a joke to suppose that the secondary officers can make amends for the defects of the first; the mainspring must be the mover."

The foe they were to face comprised Native warriors and French regulars, infantry units raised for guard duty in the naval ports of France and service in the colonies. The officers were Canadians but all other ranks were the regulars from France who were trained in drill manoeuvres of the European style warfare. Unlike most regulars, however, they were also good guerilla fighters adept at Indian warfare. They were able to travel long distances, live off the land, strike swiftly and vanish before their victims could counterattack. Great mobility, deadly marksmanship, skillful use of surprise and forest cover and a high morale stemming from a tradition of victory gave them the superiority they were about to display. Despite their competence as combatants, the French would have been in great difficulty but for their Indian allies who numbered 637 out of their total force of 891. The French commander was Contrecoeur, a leader who had knowledge and skills of wilderness warfare - raiders, ambushers, skirmishers.

Braddock had been told that fighting in the forests of America was not like fighting on the battlefields of Europe and had been warned to avoid "ambuscades." Typical of later British types who hautily came to conquer colonials, Braddock was contemptuous of forest guerilla fighters and bristled at this cautionary counsel. Braddock was "of a mean capacity, obstinate and self-sufficient above taking advice and laughed to scorn all such as represented to him that in our wood county war was to be carried on in a different manner from that in Europe." Native braves he scorned disdainfully. "They may indeed be a formidable enemy to the raw American militia, but upon the king's regulars it is impossible that they will make any impression." Braddock believed the ponderous, massed military movements of trained troops would overcome all obstacles and scoffed when told he would be lucky to see the enemy.

Washington, who had hoped to learn from this eminent major general, must have wondered at Braddock's brusque dismissal of wise advice for Washington knew Native warriors were sage and very savage opponents. Doubtlessly dismayed at Braddock's brusque dismissal of this good advice, George may have begun to have second thoughts about a leader who refused to listen to those wise to the ways of the forest fighters. Washington had joined the expedition to acquire military doctrine at the fountainhead, but here was a head who was clueless of the sort of battle they were about to fight and haughtily derisive of the warnings he had received. Braddock was so certain of his victories, commented one contemptuous Canadian writer, that he expected, "to have breakfast at La Belle Riviere, dinner at Niagara and supper at Montreal."

|

|

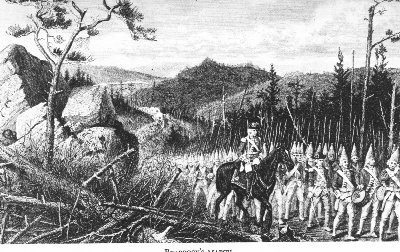

Braddock's March |

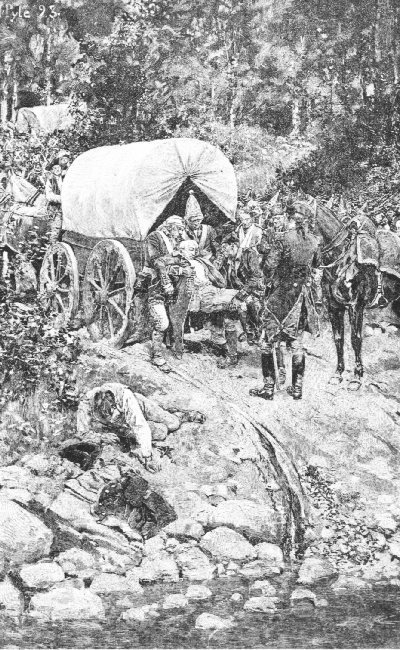

The troop finally marched out on June 10. Braddock's men made a flashy show of brilliant scarlet and bright steel as they marched towards Fort Duquesne. They expected their long file formation would impress the French with a sense of their irresistable strength. After stepping off at a brisk pace their columns slowed and halted when they hit the Alleghenies. Before his departure Braddock had written, "I have a hundred and ten Miles to march thro' an uninhabited wilderness over steep, rocky Mountains and almost impassable Morasses." The movement of the fine force through the wild, primevil forest became agonizingly slow as companies of axemen sweated and swore their way over the rocky, heavily forested Alleghenies, slashing out the 12-foot wide road along which the mile -long column snaked. The slog took 19 days with Braddock complaining all the while.

Three hundred axemen went ahead. The wonder is they moved at all for the twelve-foot wide roadway had to be hacked through forests and blasted over rock ledges. Corduroyed roads were constructed through swamps and bridges built over streams to accommodate the cattle and straining horses hauling creaking supply wagons and heavy artillery to invest the French fort. Each large, lurching gunwagon contained 8-inch howitzers (requiring a team of seven horses). In addition there were four 12-pounders, each requiring a team of five horses, as well as fifteen mortars and six 6-pounders all to be hauled over the makeshift mountain trail. Notwithstanding its tragic ending, the trek was an extraordinary military feat. Braddock's march from Fort Cumberland to Fort Duquesne was a monumental achievement in military logistics. It took eight days to cover the first twenty miles; 32 to reach Fort Duquesne.

|

|

Braddock's March |

A worried Washington wrote to his brother, "This prospect was soon clouded and all my hopes brought low indeed when I found we were halting to level every mole hill and build bridges over every brook." Braddock accepted Washingon's suggesting that they dispatch a "flying column" of 1200 lightly equipped trooops to proceed at full speed to Fort Duquesne, a suggestion that did not achieve its desired effect. This explains perhaps while Washington did not engage in widespread Braddock bashing after the disaster.

Scouts and Indian runners brought news to the French of Braddock's approach. Contrecoeur, the fort commander, feared a force of its size would overwhelm the defences of the fort. A captain made a bold proposal: that a party of French and Indian warriors waylay the English in the woods. Indian braves were called together and the captain flung a hatchet on the ground and invited them to join his party. When no one rose to the challenge he shouted, "I am determined to go. Will you suffer your father to go alone?" His dare worked and the warriors shouted their approval. They decided the only possibility for a successful resistance lay in meeting and engaging the enemy before they reached the Ohio River.

A scout returned to the fort with word that the English army was but a few miles distant. Immediately the camp came alive as chiefs and warriors danced and daubed themselves with feathers and war paint. They set off with the small French force for the battlefield where earlier Indians had sought refuge from Europeans. One of the braves, a Delaware, commented that Braddock's army was advancing in very close order and that the Indians would soon surround them, "take to the trees and shoot um all down like pigeons." On the morning of the 9th the French and their Aboriginal allies drew powder and shot and marched off to pick off the 'pigeons.'

As the sun's rays warmed and brightened the day, Braddock's army drew ever closer to its objective. British regulars in red and colonial militia in blue marched proudly in column behind beating drums and waving banners. The last formiddable obstacle was the Monongahela River. As they splashed across, fifers were shrilling out, The Grenadiers March. It was a fine force in excellent order with sun beaming off the barrels of their muskets as the stirring martial music echoed and re-echoed through the hills. Washington thought it the most splendid sight he had ever seen. How bright and brilliant the morning; how melancholy the moments to come.

So far throughout the dense forest that closed in on either side, the only fighting faced by his forces was with nature. Braddock's men had achieved a great feat of military logistics and were on the verge of success with but seven more miles to Fort Duquesne. While he earned his reputation as a bungling martinet, Braddock, who made had some attempt to ensure his columns would not be surprised, pressed on with crazed confidence to meet his fate. All the while hostile eyes watched and waited.

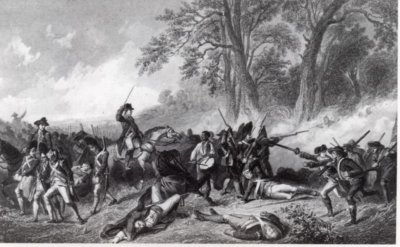

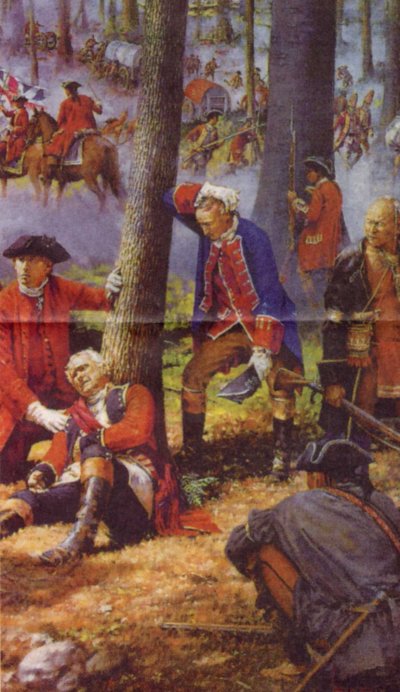

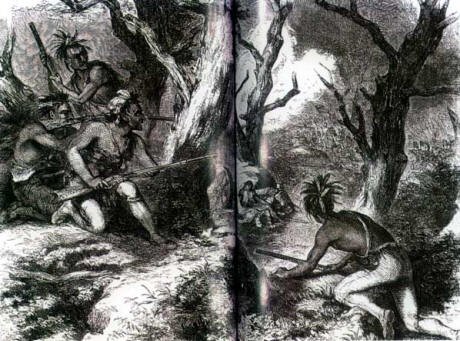

.The French and Indians headed for the high ground. It was a perfect place from which to fight, where two ravines concealed by trees and bushes formed a fine ambuscade. Shortly after they had settled in, the roll of British drums broke the sylvan silence. As the scarlet-coated forces filed by, the woods exploded with blood-curdling screams. For the first time ever, British soldiers experienced the paralyzing fear of the frenzied war hoops of the Iroquois warriors. A young lieutenant made notes of the nightmare. "I cannot describe the horrors of the scene; no pen could do it. The yell of the Indians is fresh in my ears, the terrible sound will haunt me till the hour of my death."

|

|

Indians Await Braddock's Forces |

Instinctively the French force - regulars, militia, Indians - had slipped into the woods on either side of the huddled redcoats on the open road. Long Live the King shouted the British regulars with only one thought in mind: to save their scalps. From the flanks Native and Canadian fighters bushwhacked the tantalizing redcoated-targets, who sought frantically to find shelter from the shadowy snipers. Soldiers fell right and left and soon the ground was littered with the dead and the dying with the wounded wailing and writhing in agony.

"Fire, fire, fire," shouted an enraged Braddock, as he rode back and forth wielding the flat of his sword. Because there was no visible foe to fire at, the British shot ineffectually at puffs of smoke billowing from the branches. The phantom fighters fired then vanished, invulnerable to the fusillades fired at them. In and out they sprang, appearing, disappearing, then reappearing, always rapidly firing. Their bullets were bolstered by an incessant chorus of terrifying whoops, that filled the air and made the minds of soldiers dumb with fear. Mounted officers toppled like toys, while the hideous howls and crackling musket fire issued from an unseen enemy.

Deciding to fight as their foes were fighting, some Virginians took cover behind trees and logs. Maddened at a manoeuvre that offended his conception of courage, Braddock cursing and threatening with furious menace drove them back into line to be mowed down like grass. Undaunted, a bellowing Braddock with sword in hand rode up and down the ranks beating with the flat of his weapon any of the stunned soldiers who attempted to take cover from the carnage. As soldiers fell fast and officers fell faster, discipline collapsed and the red ranks were reduced to a milling mass of frightened, frantic men. It was charged later that Thomas Gage as commander of the advance party should have controlled the chaos at the head of the column which caused the disorganization of the main force. Gates "failed to take possession of the higher ground from which the French and Indians launched their attack."

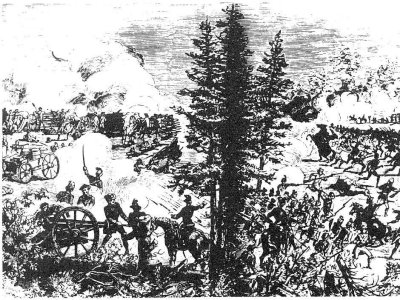

|

|

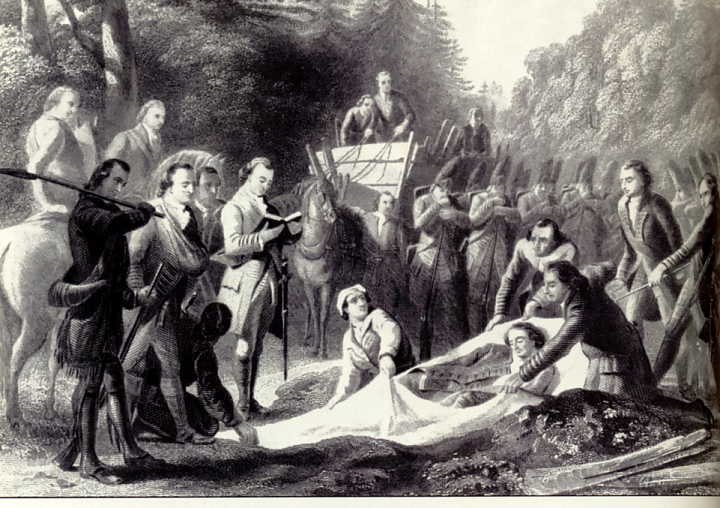

Braddock & British Slaughter. |

It was a piteous spectacle to behold. The British army dissolved into a complete and utter shambles. Ceasing to advance, the beleaguered troops became an enormous British bullseye, franticalyy firing off their twenty-four rounds of ammunition in a most confused manner, "some into the air, some into the ground." The few surviving officers lost complete control of their men and were unable to organize an effective counterattack. As the slaughter became more than flesh and blood could stand, the ranks quivered, wavered and broke, melting into a shapeless scarlet mass. Retreat turned to rout and rout to slaughter, as men froze and fell. Amid the shots, shouts and screams of war, the redcoats, wrote Washington, "broke and ran as sheep before the hounds." The few who did remain fought with fierce tenacity, but they "knew only death" from the terror of the tomahawk. "The groans, lamentations and cries of the wounded for help were enough to pierce the heart of the adamant."

A British officer raged about the rout of the redcoats. "Worse than any militia I ever saw. Cowardly principles, frightened now almost of their own shadows of the name Indian. Behind them they left the guns, the big brass twelves and sixes, the howitzers and the mortars that had so laboriously been manhandled over the mountains. Behind them were wagons, packhorses, cattle, clothing, utensils and furniture to say nothing of 25,000 specie and nearly 500 dead British and American soldiers. "