foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

THE BATTLE OF FALLEN TIMBERS

History is a pattern of timeless moments.

Some two hundred years ago the Fifteen Fires, the Aboriginal name for the United States, were poised perilously on the brink of war with Great Britain. By the early 1790s thousands of Americans were laying claims to large portions of the Ohio territory. In that chaotic and shifting frontier region, intrigue and conflict marked the meeting between Native and American settlers. Collusion and collisions were commoplace there at the edge of the empire. The collisions occurred as Indian warriors fought to hold preserve their homeland heritage from the seemingly endless stream of American settlers, all seeking a piece of the rich farmland of the west. Collusion occurred continually between Aboriginals and British agents, both intent on the Aboriginal maintaining ownership of the wilderness. The British reason for this was not all altruistic, for they hoped a Native buffer zone would result in the separation of British settlements in Upper Canada from Americans settlements in the land on the east side of the Ohio River.

Savage encounters between Native braves and American settlers occurred with routine regularity in the northwest. President Washington somewhat blindly and quite bluntly, attributed the Aboriginal hostility, not to nervous natives simply attempting to save what was theirs, but rather the work of British provocateurs. While British agents were counselling native caution and concern, the real reason was the frantic fear on the part of the Aboriginals that their land was rapidly being lost forever to the white hoards, whose lust for land never seemed to be satisfied. From his base at Navy Hall in Newark, Lieutenant Governor Simcoe naturally denounced these allegations and heatedly denied that his 'henchmen' were behind Aboriginal incursions into the fledgling frontier settlements.

Britain's continuing occupation of posts on American territory exacerbated the problem. Thomas Jefferson, Washington's Secretary of State, routinely blasted the British for their stubborn retention of the western posts, which according to the terms of the treaty that ended the American Revolution, were supposed to have been relinquished to the United States "with all convenient speed." Eleven years had passed and the posts were still garrisoned by British troops. Jefferson charged that Britain's refusal to abandon the posts was the real reason,

In His Own Words,"for the recurring loss of American blood and treasure."

|

|

Thomas Jefferson |

Native sachems had designated the Ohio River as the boundary between their tribes and the surging settlers. Their stubborn insistence on this dividing line was blamed by Americans on the scheming of British officials. Americans charged that a steady stream of muskets, balls, provisions, powder and vermilion for war paint, flowed directly to the tribes from depots and arsenals in Canada. They accused Governor Simcoe and his superior, Lord Dorchester, of attempting to mobilize the might of the Natives to force the United States to accept an Aboriginal satellite state north of the Ohio to serve as a neutral buffer zone between Upper Canada and the United States. For this reason, while the British did not want war between the Americans and the Aboriginals, they secretly supported with words and weapons Native opposition to American expansion into the west.

|

|

Lord Dorhcester & Governor Simcoe |

This simmering brew was brought to a boil by the public pronouncement of one of the sovereign's top servants in Canada. In February 1794 to a large meeting of Indians of Lower Canada, Dorchester used the occasion to warn them of the dangers that threatened the country. He said he hoped an agreement would have been reached regarding a new, definite boundary between the Americans, Canadians and Indians, but this failed to occur. As a result, he said, "I shall not be surprised if we are not at war with them in the course of the present year and if so, then the line must be drawn by the Warriors' children." He undiplomatically declared, "War is inevitable."

John Randolf, who by this time had become the American secretary of state, called this comment "hostility itself." To add insult to injury, two Pottawattamies taken prisoner by General Anthony Wayne's troops during the frontier fighting, said that Simcoe had promised to march to their assistance with fifteen hundred men.

In Their Own Words,"All the speeches received from him were red as blood. All the wampum and feathers were painted red."

The Americans received a different story from several Shawnee prisoners, who claimed they could not depend upon the British for effectual support. "They are always setting the Indians on like dogs after game, pressing them to go to war, but not helping them."

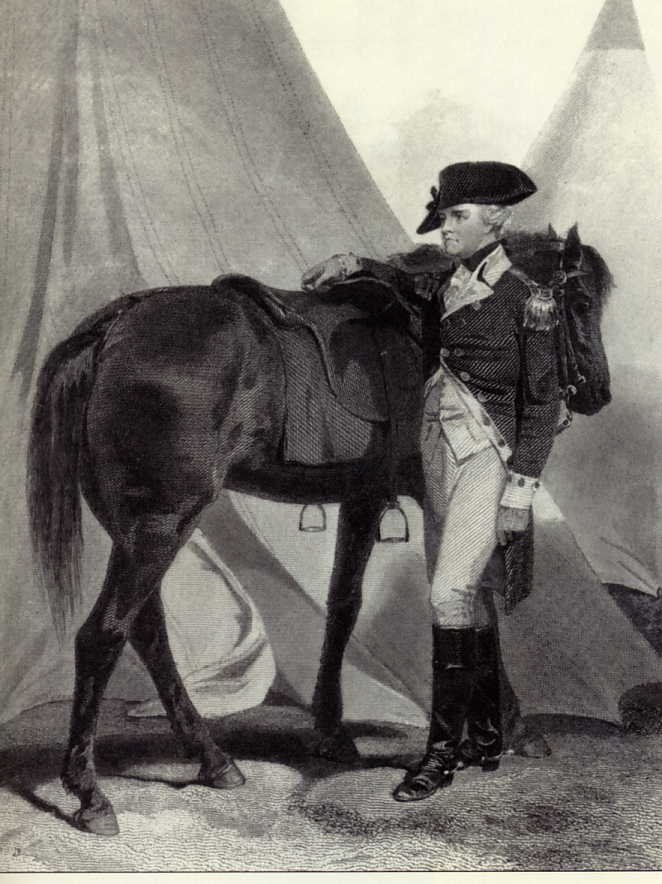

When peace talks between three American commissioners and the western Natives failed, President Washington ordered Brigadier General Anthony Wayne to deal with the Indians. He promptly assembled his forces for combat. Dubbed "Mad" Anthony during the revolutionary war, because of his headlong, heedless, impetuous nature, Wayne took command of his so-called army at Pittsburgh. He worked with the misfits and castoffs for nearly two years before finally turning the rabble into a rough, tough frontier force. Washington gave him permission to strike and strike hard.

|

|

Brigadier General "Mad" Anthony Wayne |

Fearful that an American victory would allow Wayne to menace the British garrison at Detroit, Lord Dorchester ordered Simcoe to undertake a delicate, dangerous and very undiplomatic mission: the re-construction of Fort Miami on American territory. The fort, which was located beside the Maumee River rapids at the western end of Lake Erie some 50 miles southwest of Detroit, had been abandoned by the British at the conclusion of the American Revolution. It was now considered the best point at which to meet any American threat to Canada's southwestern frontier.

The re-construction of this protecting post in the Ohio country was begun in April 1794 on Simcoe's orders by the British commandant at Detroit, Lieutenant-Colonel Richard England. The location of the fort was critical, for the confrontation was expected nearby between Americans and the Delawares, Shawnees, Miamis and several other western tribes from the Ohio country. Construction by the British of a fort on American territory naturally impressed the Aboriginals and led them to believe, mistakenly, that Britain was about to enter the war as their ally in defence of Native rights.

|

|

Map of Battle of Fallen Timbers and Fort Miami |

In this rapidly worsening atmosphere, brutality on both sides was widespread. Few of those taken captive escaped brutal treatment, however an exception to this savagery occurred because of Colonel England, a a six-foot six-inch British officer. England was a man of "large dimensions," noted for his "cheerful, open countenance and his humane, gallant character. In the bloodthirsty struggle between Americans and Aboriginals, no quarter was asked or given and captives usually faced a cruel end. Fifty American prisoners expected as much when they were captured by the Indians, however, at his own expense, Colonel England bought their freedom from their captors and sent them safely home. Their gratitude was boundless for this "gentleman and man of great humanity."

In a letter written two days before the big battle, Simcoe informed Lord Dorchester that he was about to leave for Detroit "with all the force I can muster." Simcoe believed the Americans were about to invade Upper Canada and when they did, Fort Miamis and Detroit would be the first to feel Wayne's violent assault. With an eye to history, Simcoe feared his failure to resist the Americans would ruin his reputation.

In His Own Words"I cannot flatter myself with much hopes of repelling Mr. Wayne and feel that my character as a Military Officer must suffer in the extreme and as a result, occasion the loss of the Canadas."

Fort Miamis was only partially completed by August 20th, 1794, the date of the decisive battle at Fallen Timbers. The Aboriginals had chosen to make their stand on the banks of the Maumee River, near the present-day city of Toledo, Ohio, almost under the guns of Fort Miamis. Their left flank was secured by the strong rocky bank of the river. On their right was a dense forest through which a tornado had recently roared, its wild winds cutting a swath of devastation through the forest a mile long and hundreds of yards wide. The chaos had created a wild tangle of uprooted trees and twisted branches in which the Aboriginal braves hoped to hit and then hide with their customary cunning and ferocity.

|

|

|

'Mad' Anthony Wayne |

|

|

'Mad' Anthony Wayne |

As the American force advanced to meet the Natives, the cut-and-thrust field commander sent word to the warriors that he was prepared to parley. His military might, he said, was not directed at the Natives, but at the expulsion of the British. The sachems said they were willing to 'treat,' but as was customary with them, a lengthy delay and long deliberations were required before they laid down their arms. They said they needed time and demanded ten days and a halt to any further military movement. Wayne ignored their request and pressed on with his troops.

As was their custom before conflict, Aboriginal braves observed a strict fast, a total abstinence from food of any kind commencing the day before they expected the battle to begin. On the day of the expected assault, they had hidden in ambush to await Wayne's arrival. The day came and went and no Wayne came. After another period had passed, the famished fighters could wait no longer and left their camouflage to feast.

The fight came in the fog of morning. Wayne struck on August 20th, a wet, wildly tempestuous day. Black Snake, as Wayne was known among the Natives, was as wary and wily as the foe he fought because he had made the Native warriors' mode of warfare his own.

Wayne's excellent intelligence informed him of the braves' every action and when he learned they had left their ambuscade, he attacked with a vengeance. The carefully planned manoeuvres were perfectly executed by his officers, who wore white, red, yellow and green plumes to mark the columns they led. Wayne's troops struck with sabres flashing and horsehair plumes flying. The Light Dragoons charged from the left, while from the right the infantry poured on volleys of hot musket fire followed up by the cold steel of their bayonets.The Natives were unnerved by the confusion caused by Wayne's unexpected appearance and bewildered by his sudden assault. They attacked Wayne's left column in "a most gallant manner," but were forced to yield to greater numbers. With several of their principal chiefs killed in the chaos, the warriors floundered then took flight. Beaten in battle and butchered as they fled, they were driven more than two miles by the exultant soldiers, hollering and hitting with every means at the disposal, their madly fleeing foe. The braves ruefully admitted later

In Their Own Words"We could not stand up against the sharp ends of the guns."

|

|

Flight From The Sharp Ends of Their Guns |

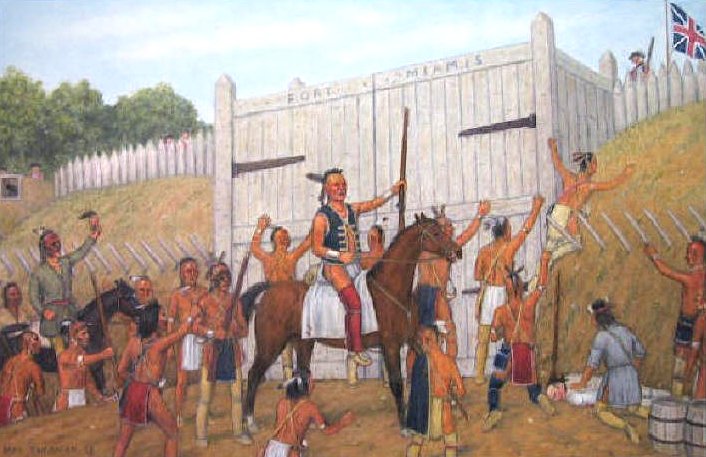

In less than an hour, the fight at Fallen Timbers was history. Though a hundred militia from Detroit had fought with the Aboriginals, the British regulars at Fort Miami barred the gates to Natives seeking safety there from the wrath of Wayne's troops. This turned out to be the most significant part of the battle - the refusal of the British commander to shelter their former Indian allies from the savagery of the pursuing American forces. British military policy was that the Native warriors were on their own. Henceforth, they would have to cope with the might of America by themselves. Among the warriors was the Shawnee brave, Tecumseh, who later bitterly reminded the British of the day, "the gates were shut against us."

|

|

"The gates were shut against us." |

This failure of the former ally to assist them in their hour of need was long remembered by the Aboriginals and made them more cautious about backing Britain in the war to come.

|

|

General 'Mad Anthony' Wayne 1791 |

The victory was decisive, complete and cruel. Aboriginal families were routed, their villages burned, their winter corn destroyed, their fertile fields laid waste for twenty miles on either side of the river. Before Wayne withdrew he ordered everything burned and what one onlooker called "one of the most beautiful landscapes ever painted" was turned into a smoking wasteland. The army later returned and "cut down and destroyed hundreds of acres of corn and burned several large town besides the small ones." An estimated thirty thousand to forty thousand bushels of grain were destroyed. Those the war had spared, now succumbed to starvation.

Wayne had soundly defeated the Aboriginals and they knew he would do so again. The battle was a watershed for the western tribes. No more would they live and love on the banks of the beautiful Maumee River. Soon forests would fall to the settler's ax for the time of the whiteman had come.

Fresh from their triumph, flushed with victory and spoiling for another fight, a party of Wayne's horsemen raced to nearby Fort Miamis approaching to within gunshot range of the unfinished fortress. The post's young commander, Major William Campbell and his tiny troop of redcoats, cocked their muskets, loaded the cannon and prepared to face the onslaught. They knew their chances of survival were slim, for no British force then in the area could resist Wayne's direct attack.

|

It was a precarious moment. A single shot would have shattered the peace of North America. Fortunately, both men decided that discretion was the better part of valor. Neither was prepared to fire the first shot. Shortly, thereafter, Wayne's army withdrew and the British breathed a sigh of relief.

|

|

Fallen Timbers Today |

Today the site of the battle, Prophet's Town, Lafayette, Indiana, where Tecumseh and his brother, the Prophet, tried to organize a great Indian confederacy to combat the ever-encroaching white settlements, contains no above-ground remains. A plaque placed by the Battleground HIstorical Corporation is southeast of the battleground.

Copyright © 2013 Website Administrator