foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

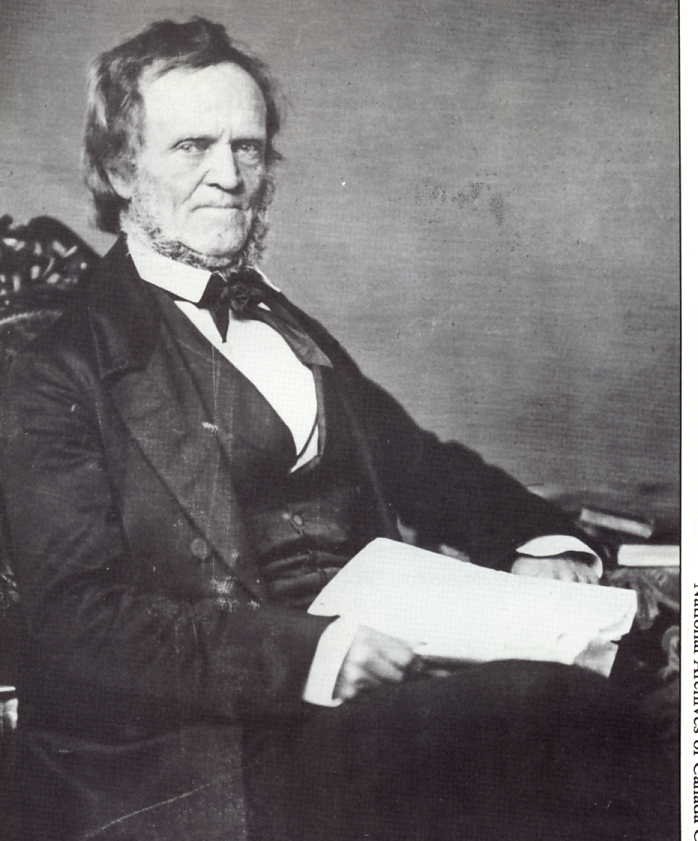

WILLIAM LYON MACKENZIE, PART 2

History reviews the successes and failures of men and women.

|

|

William Lyon Mackenzie |

Politics was his passion and Mackenzie, who fervently believed in an "unfettered press," used the Colonial Advocate to denounce the leading denizens of society and to urge his readers to press for a more representative form of government. As early as 1824 he advocated the confederation of the British North American colonies. Always a crusader for democracy over autocracy, Mackenzie championed the cause of the common man and woman and the struggle of the many against the few. He raged against land speculators, hypocritical clergy of the Church of England and dishonest officials. In order to be closer to the political action, he moved across the lake to Toronto in 1825.

At a time when moderation in speech and writing was rare, his paper became the mouth-piece of a man determined on stirring up society. Mackenzie pointed out the injustice and absurdity of the existing state of things, where the people were beguiled with a mockery of representation in Parliament, without having any voice in the nomination of the persons forming the government of the day. Those exercising the power made no attempt to disguise their control nor distort the real facts of the case. They flagrantly avowed their independence of public opinion and sneered at arguments founded on the doctrine of ministerial responsibility.

Mackenzie wasted neither time nor his considerable talents and targeted any cause that came into his 'ken' with his long-winded, meandering style. He blasted broadsides at the Family Compact, a select group of men linked by political, social and religious ties. This close-knit clique exercised control over government that was completely independent of the people

|

|

|

and their representatives. Mackenzie's caustic comments about the governing elite included such terms of endearment as "tools of a servile power, official fungi, pestilential sycophants and villainous despots." The objects of his venomous epithets gave as good as they got, losing no opportunity to discredit this "reptile" and his "poisonous paper" which they took delight in labelling "a rabble-rousing rag." Through the columns of his paper Mackenzie poured out much bitter invective. What he said was for the most part undeniably true but he had such an offensive way of expressing himself he brought down upon his head the rancorous hatred of those whom he made the object of his attack.

Within six years of coming to Canada, Mackenzie developed from being an unknown peddler into a public critic. In the process, the "conceited red-haired fellow" was transformed from a person of no significance to a persona non grata in the eyes of the Family Compact. The exploits of this fiery fellow in Upper Canada during the 1820s and 30s was the saga of a personality and a period, for the Little Rebel had a starring role in the politics of the period that simmered then boiled into rebellion.

As time passed, however, Mackenzie encountered serious difficulties. The Advocate was in financial trouble. Subscribers postponed paying and the cost of collecting reduced profits to little or nothing. Publication of the paper was irregular and the intervals between issues were often lengthy, creating problems with its pressing costs and disappointment and dissatisfaction to its patrons. In fact, the paper was on its last legs if not already dead.

Then fortune intervened to favour Mac and his printing press, thanks to Mackenzie's enemies' lawless devastation. A gang of rowdies, the sons of members of the Family Compact, bent on preventing publication of his hated rag, broke into Mackenzie's office and wrecked his printing plant. Their vandalism aroused much popular indignation against the perpetrators and passionate support and sympathy for their victim. The lawlessness gave the paper a new lease on life, for Mackenzie sued for damages and won. With the generous compensation he received, he bought a better printing press and resumed his attacks with renewed and reinvigorated vengeance.

|

|

|

The monument to Sir Isaac Brock was being constructed and Mackenzie decided that a copy of the tabloid should be entombed within the column. He reverently wrapped it in otter skin and placed it inside the monument where, he said, "It would be removed by some future generation which shall discover it hid among the wreck of ages." It did not last quite that long.

|

|

|

When Lieutenant-Governor Sir Peregrine Maitland learned of its presence in the tribute to the titan, he was outraged and ordered "that rag removed." Carrying out the governor's command was accomplished at considerable cost, for it necessitated pulling down some 48 feet of the newly completed masonry. Money to Maitland was of no consequence, so long as the wretched rag was removed from the monument.

While Mackenzie oftimes appeared to be a lonely voice crying in the wilderness, he had numerous sympathizers. Throughout the years of pandemonium and persecution in which he campaigned against the Compact, he was to use his own words, "shielded by the powerful protection of public opinion and popular sympathy." Nick-named the "People's Tribune," Mackenzie was triumphantly re-elected by residents of York County in four by-elections. People flocked around his make-shift platforms to hear the short, barrel-chested, shrill-voiced speaker rant and rave and shake his clenched fist against the Family Compact whose members, he charged, "swallowed bribes like sweet morsels."

|

|

Parliament Buildings in Toronto Where Mackenzie Sat As A Member of the Legislature |

His devoted admirers presented the People's Tribune with a valuable gold medallion and a massive chain on which to hang it "as a token of the approbation of his political career." His Compact critics contemptuously labelled it a "gingerbread" medal. Even when forced to flee the province following the rebellion with 1000 pound bounty on his head, [See Below *] the subject of a widespread militia manhunt, Mackenzie's presence was never betrayed. He was fed and sheltered along his escape route by sympathetic citizens whose courageous acts were performed at fearful cost to them and their families if they had been caught.

|

|

|

,Lieutenant Governor Francis Bond Head decided to confront and defeat Mackenzie and his Reformers and threw down the gauntlet by calling an election in 1836. The Queen's representative then stormed about the province campaigning with all the vigor and skill of a seasoned politician. Using threats and bribery, the Tories trounced the Reformers. Outbreaks of violence followed the tumultuous election which saw Bond Head and his Tories triumphant and the Reformers devastated. The collapse of the Reform Party and the gloating of Head, who gloried in the Compact victory, drove radical Reformers to despair. Because constitutional change had failed, the fiery extremists began to believe that action on the American model was next.

|

|

William Lyon Mackenzie and Sir Francis Bond Head |

Given the fact that most of the people in the province shared the same grievances at the hands of the ruling class, it is difficult to understand why Mackenzie received so little active support for his uprising. Despite the flagrant injustices that existed in the little society, most Upper Canadians appeared willing simply to accept them "lying down." Most pioneers in Upper Canada reflected in their day to day life the same characteristics of their American bothers save one: a fierce desire to control the political situation.

Democracy was not high on the list of the Loyalists. While it was easy to understand the restless spirit of the common folk who sought reform, it was far more difficult to explain the contentious Toryism of others in the same social scale. One visitor to the province remarked on the extreme Toryism of the lower classes newly arrived from Britain. "While they were Whig and radical in the mother country, these humble folk newly arrived from Britain, after becoming possessed of a few acres of forest in Canada, seem to consider themselves part of the aristocracy and speak with horror of the people and liberality." For those basking in the sunshine of official favour, the unrest and rebellion of the few were base ingratitude. Considering the risk to life, limb and property, a good many others were undoubtedly simply fearful of their fate. For them the dangers of protest were just too great.

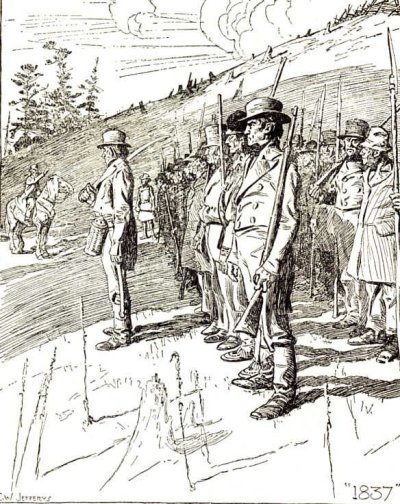

Mackenzie attempted to reorganize the shattered Reform party, but his efforts resulted in little but defiance and fisticuffs. From fighting to firearms was one step, but from carrying guns for self-defence to drilling in their use to fight officialdom was quite another. Throughout 1837 the press regularly reported on Reformer military manoeuvres and rumours of their secret production of pikes. In October 1837 a young Reformer marched down Yonge Street bearing a white flag on which were inscribed in large, black letters the words, LIBERTY OR DEATH. His makeshift banner was planted firmly in the ground in front of a house in which Reformers were holding a meeting. A Tory on his way to a meeting of Tories chanced to pass by the house, saw the flag flapping in the wind and said to a friend, "I am going to take that flag and if they catch me, I will have a job on my hands." After a brief tussle he took the hated pennant and raced to the Tory meeting, where the "rebel rag" was torn into strips and tied to the tails of their horses. Political events went from bad to worse. A crisis was in the making.

The rebellion in Upper Canada was double trouble: it represented a crisis in imperial relations and an internal social struggle made worse by am economic downturn that saw high unemployment and tough times. In a Declaration of Reformers published in THE CONSTITUTION on August 2, 1837, reformers declared that Americans at the close of a successful revolution had formed a constitution of their own, "The Loyalists now peopling this portion of America are entitled to the same liberty without the shedding of blood - more they do not ask; less they ought not to have." In 1837 a reformer published a book in London in which he warned that "the people would rise if things went on unchanged. Arms and ammunition have long since been secured. The days of 1776 are again to be renewed in 1837."

|

|

Rebels Drilling in North York 1837 |

The father of the Upper Canadian rebellion was William Lyon Mackenzie, a "wiry and peppery little Scotsman" who was honest, brave, energetic and ruthless in his exposure of wrong and wrongdoers. He was a man of strong personality but often intemperate in word and deed. Elected a radical member of the Assembly in 1828, Mackenzie was expelled therefrom again and again only to be re-elected each time by a devoted and enthusiastic constituency. His vituperative pen roused bitter enemies who railed against him resulting on one occasion on the sack and destruction of his printing press. A born agitator, Mackenzie was more able to engender strife and struggle than the patience and prudence needed to organize and effectively command large forces of fighters or the judgement and statesmanship essential to political reorganization and renewal.

Mackenzie orchestrated large public meetings throughout Upper Canada in the summer and early fall of 1837. Three or four dozen meetings were held and Mackenzie was at most of them.

"Canadians!It has been said that we are on the verge of a revolution. We are in the midst of one; a bloodless one, I hope." He described Head as "the puffed up, angry little creature who sits perched on a mahogany throne in a chamber here in Toronto playing the petty tyrant of the hour." When nothing the Reformers did resulted in redress, some began to believe that anything less than the complete overthrow of the system would be a waste of time. In November 1837 Mackenzie threw caution to the winds and hurled a provocative challenge directly at his Reformer followers. "To die fighting for freedom is truly glorious. Who would live and die a slave? Come if you dare, here goes! Rise Canadians!"

|

|

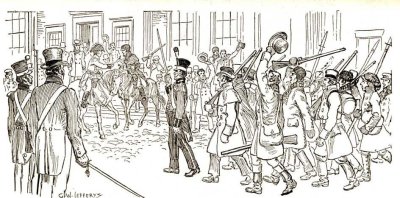

Rebels On the March Down Yonge Street to Attack Toronto, 1837 |

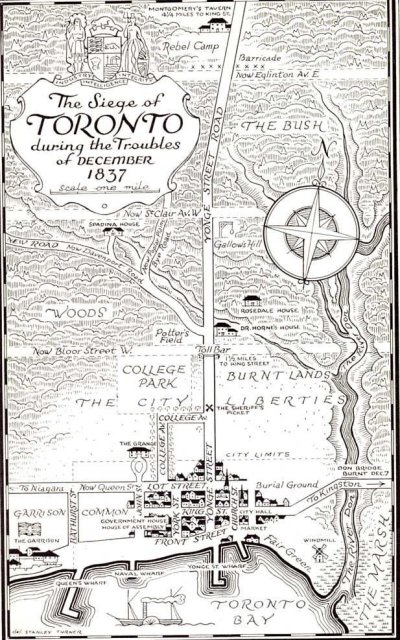

The rebels gathered at Montgomery's Tavern [**] on Yonge Street to plan strategy. During their arrival at the tavern, Lieutenant Colonel Robert Moodie suddenly appeared and when he attempted to ride through the throng to warn the lieutenant governor of their assembly, four shots rang out and Moodie fell from the saddle.

|

|

The Death of Robert Moodie |

That same night another government supporter John Powell was captured by two rebels and while he was being led away, Powell pulled a gun he had hidden and killed one of the rebels.

|

|

Powell Pursued by Rebels |

In the confusion he mounted his horse and raced for York to warn Head. The alarm went out and Loyalist volunteers responded quickly

|

|

Loyalist Volunteers Assemble at Parliament Buildings, Toronto, December, 1837 |

Some of the rebels who responded to Mackenzie's call to arms decided after sobre second thought that the exercise was hopeless and counselled calm and speedy dispersal. Other more highly motivated individuals pressed for an immediate attack on the defenseless city. Their heated arguments were interrupted by word that a force of Head's government supporters including pistol-packing Head and led by Colonel James Fitzgibbon was wending its way up Yonge Street.

|

|

Toll Gage at Bloor and Yonge Streets 1837 |

|

|

Yonge Street |

Unless the rebels disbursed they would soon be forced to face and fight the royalists whether they wanted to or not. Both rebel and royal forces suffered from the same handicap: ineffective leadership. Head was no military leader, but then neither was Mackenzie. The Little Rebel failed to ensure secrecy and surprise, had little capacity for administration and could not keep his head in a crisis.

However, what he lacked in leadership he more than made up for in energy. Vowing victory 'General' Mackenzie prepared to lead his ragtag rebels into battle. Wrapped in several overcoats to ward off bullets as well as the bitter cold, he mounted a white farm horse and set off with roughly a thousand ill-armed supporters down Yonge Street to meet and beat Fitzgibbon's forces and overthrow the government. As they set off they sang the Upper Canadian Rebel Song of 1837.

Up and waur them a' Willy,

Up and waur them a'

Better brave the tyrants down

Than let this country fall.

The total number of rebel supporters in York County and beyond was not known but it has been suggested that if they had acted with dispatch they could have caught Toronto unawares and captured the city. That, of course, presupposed planning. Men had to be organized, fed and armed - basic requirements that somehow were neglected. Neither was it necessary for the rebel attackers to set forth armed only with pikes and pitchforks when some six thousand unguarded weapons could have been seized in a quick raid. As well shotguns must have been available throughout the country and and these would have been formidable against inexperienced defenders. Passion not planning ruled the day, however, and as a result the rebel raid was destined to fail.

In the last light of day shadowy figures led by a rider on a ghostly horse encountered a squad of twenty-seven very nervous government supporters at William Sharpe's garden, the site today of Maple Leaf Gardens. There was a flash and a great blast from 27 government muskets. The front rank of the rebels returned the fire and then dropped to their knees to provide a clear shot for the second rank. To rebel riflemen in the rear the sudden disappearance of their brave comrades came as terrifying shock for it seemed that all had been shot. Fearing a similar fate the remaining rebels took off in all directions. [***]

The militia forces, which included a 22-year old militia private named John A. Macdonald, marched to the door of Montgomery's Tavern where the order was shouted to any inside to come out and surrender. By this time few rebels remained. Most had earlier tumbled out of the back door and headed for the hills. The place was ransacked by the militia and in a small room used by Mackenzie incriminating papers were found bearing the names of many of the dissenters. Bond Head was overjoyed and immediately issued a proclamation ordering the arrest off all named rebels and placing a 1000 pound bounty on Mackenzie's head. Bond Head rejoiced in their success and said they had subdued that "demon democracy."

|

|

The Battle at and the Burning of Montgomery's Tavern |

Sir Francis mounted his horse, pointed toward the tavern and with theatrical effect commanded curtly that the vile nest of murder and treason be burnt. Torches were immediately applied to the building and as the inferno lit up the sky the tiny figure of Sir Francis was outlined against the flames pointing north and ordering a militia detachment of forty to follow the fleeing rebels. Galloping Head then return from the field of victory eagerly anticipating the wild welcome awaiting him for saving the city from ruin. The flames of Montgomery's Tavern, said Head

In His Own Words

"was a lurid telegraph which intimated to many anxious and aching hearts at Toronto, the joyful intelligence that the yeoman and farmers of Upper Canada had triumphed over their perfidious enemy - Responsible Government."

Mackenzie's Rebellion, which could have been the clarion call to a great popular movement for a proud people, was instead a dismal fiasco. Little Mac and his motley group fled for their lives to the border. With big bounty on his head Mac became the subject of a widespread militia manhunt. Despite the huge reward offered for his capture, the People's Tribune was never betrayed. The lion-hearted Patriot was supplied and sheltered by sympathetic citizens, action which was very courageous for it could have cost them dearly had they been caught. Mackenzie must have found "their love and loyalty sweet nectar after the bitter brew he had just been forced to drink."

|

|

|

For nearly thirty years Mackenzie had fought for a principle at the price of poverty, imprisonment and exile, destitute of all but hope, faith in the right and belief in himself. After eleven years as an outlaw in the United States - he was the last of the rebels to be pardoned - he returned to the city of which he was the first mayor reaching Toronto in March 1849. In spite of his 13-year banishment his name and presence still worked magic with Ontario voters. Within a year of returning to the province from his long exile in the United States, he was elected to the Legislature by the ratepayers of Haldimand County. He gave his opponent, George Brown, the Grit's greatest leader and the founder of the Globe and Mail, a political thrashing in the process.

Although responsible government had been achieved while Mackenzie was in exile, he did not like the new political organization which combined Canada East (formerly Lower Canada) and Canada West (formerly Upper Canada.) Never one to keep quiet about his opinions, Mackenzie took it upon himself to let the residents of Canada West know about his opposition to the union in a series of speeches he made around the province. The poster below publicized those lectures. While officiadom took little notice of Mackenzie's impassioned lectures, it is interesting to note that this union did not work out and it eventually resulted in the Dominion of Canada.

Bill, thank you for replying so promptly. I would be very grateful for the book details when you get a chance. I do need to reference my research, so this would be especially helpful. best wishes Lin Mackenzie remained in the Assembly until 1858 when he retired from public life. From 1853 to 1860 he published a weekly paper Mackenzie's MessageOver 3000 of Mackenzie's friends took up a collection and in 1858 bought the impoverished public defender a house on 82 Bond Street in Toronto, where he lived out the last two years of his life and died in 1861 at the age of sixty-six. The house that today serves as the Mackenzie Museum is supposed to be the most haunted house in Toronto.

Rebel's Haunted House

Tales have been told many times through the years of supposed ghosts at the mid-Victorian home. Caretakers Mr. and Mrs. Alex Dobban and Mr. and Mrs. Charles Edmunds told of a series of experiences which they believed were linked to the ghosts of William Lyon Mackenzie and his wife Isabel. - a short, frock-coated man whose detailed description seems to match William Lyon Mackenzie has been seen at night in the third-floor bedroom.- A woman, long hair hanging about her shoulders, has appeared on both the second and the third floors.

- A little 'antique' piano has played in the moonlit main parlour after the house was locked and the care-taker's family had retired for the night.

- Phantom footsteps have been heard on the building's wooden stairs.

- On one occasion the ghostly lady reached out and slapped the caretaker's wife, leaving three distinct welts on her cheek. Whatever the ghost stories may or may not reveal about the supernatural, imbedded in them are clues to historical truths.

|

|

|

Although a dauntless campaigner who in public was perpetually in motion, Mackenzie suffered black depressions in private. The tormented tribune for disaffected colonists led a lonely life filled with heartbreak and depression. But while he was often bloodied, his head was never bowed. One of his most praiseworthy qualities was his perseverance in the face of frustration and fierce opposition. "Let us play our parts here like men," he urged his son, "fearless and faithful trusting that in due time we shall reap if we faint not." He maintained that unyielding temperament even to the last.

On the 28th of August, 1861, the little Scot entered a deep coma and towards evening died. Beside him was his Bible in which he had circled, "Behold I cry out of wrong, but I am not heard. I cry aloud but there is no judgement." Mackenzie's voice was heard and his contribution to our history heralded by Canadians. Not the least of his pride as a printer would be the knowledge that his Queenston home is today an honoured historic site which houses the Mackenzie Printery Museum, Canada's largest operating printing museum. How proud and pleased the constant crusader would have been to know that he helped steer Canadian history in a new direction, that his name is a proud part of our country's heritage, and that his grandson, William Lyon Mackenzie King, became the longest-serving prime minister of a great country called Canada.

|

|

William Lyon Mackenzie King, Prime Minister of Canada |

This slight,wee, wiry man was the record-holder of a number of firsts in the province.

He was:

(a) the first Upper Canadian to speak about the principle of responsible government.

(b) the first mayor of Toronto and the designer of the city's first coat of arms.

(c) the first man to be ejected from the House of Assembly four times and promptly be re-elected each time.

(d) first among Ontario's nationalists.

(e) the only Canadian ever to declare independence for the province and declare it a republic. .

[*] the equivalent of a quarter million dollars in today's terms

[**] Today the site of a post office just north of Eglinton Avenue. [***] The following was taken from the Toronto Star April 29, 2007Men in the Shepard family were known across the country as reformers, Thomas Shepard recalled in his story of the 1837 rebellion as recorded in Landmarks of Toronto by John Ross Robertson. "The night of the rebellion," Shepard wrote, "Mackenzie ordered us to march down Yonge Street and away we went. He led us. I was in the front rank along with Thomas Anderson and his brother John. Sheriff William Jarvis and other 'Tories' fired shots. ..if our fellows had only been steady we would have taken the city that night. I don't know what started our men running, but most of them made off up Yonge Street as fast as the other fellows did down to the town. For a while some of us at the front stood our ground and I was firing away among the last of them."

Shepard, who was intent on escaping to the United States, spent the night of the rebellion at a Kingston Rd. tavern. It's not clear why he backtracked, but after taking a trail through the woods with Anderson and his brother Michael, he recalled, "that night we slept at the house of a friend east of Yonge St." Shepard and the others were eventually arrested but never tried. They were sent to Fort Henry at Kingston and fearing they would be taken to Australia they escaped. They fled to New York state and after three years were pardoned.

In 1849 the Parliament of Canada, then located in Montreal, passed what was called the Rebellion Losses Bill to compensate those who had lost property during the rebellions of Upper and Lower Canada. The legislation was subsequently signed by the Govenor General Lord Elgin, who while he had reservations about it, felt if the colony were ever to become independent, he had to confirm Parliament's decision. Emotions were so high during consideration of this legislation, John A. MacDonald, subsequently, the Dominion of Canada's first Prime Minister, almost became involved in a duel. Tory tempers were still simmering and the very thought of compensating French Canadians who had rebelled, enflamed them to such an extent, they raged, pelted eggs as Lord Elgin and stormed the parliament buildings. During the rioting, the imposing structure, newly built to house the parliament of the United Provinces of Canada (union of Onario and Quebec), was set on fire.

|

|

Parliament Burns by Joseph Legare. |

National Post, July 18, 2011

Under Montreal archaeologists search for charred scraps of Canadian parliament

Following the blaze, the two-storey structure was described as a total loss. Nevertheless, archaeologists suspect ample evidence of the building remain underground since 1850s contractors would simply have rebuilt on top of the charred rubble. Since the 1920s, the site has been a paved parking lot.

|

|

Archeologists Recover Ruins of Parliament Building |

[****] National Post 15.10.2008

|

|

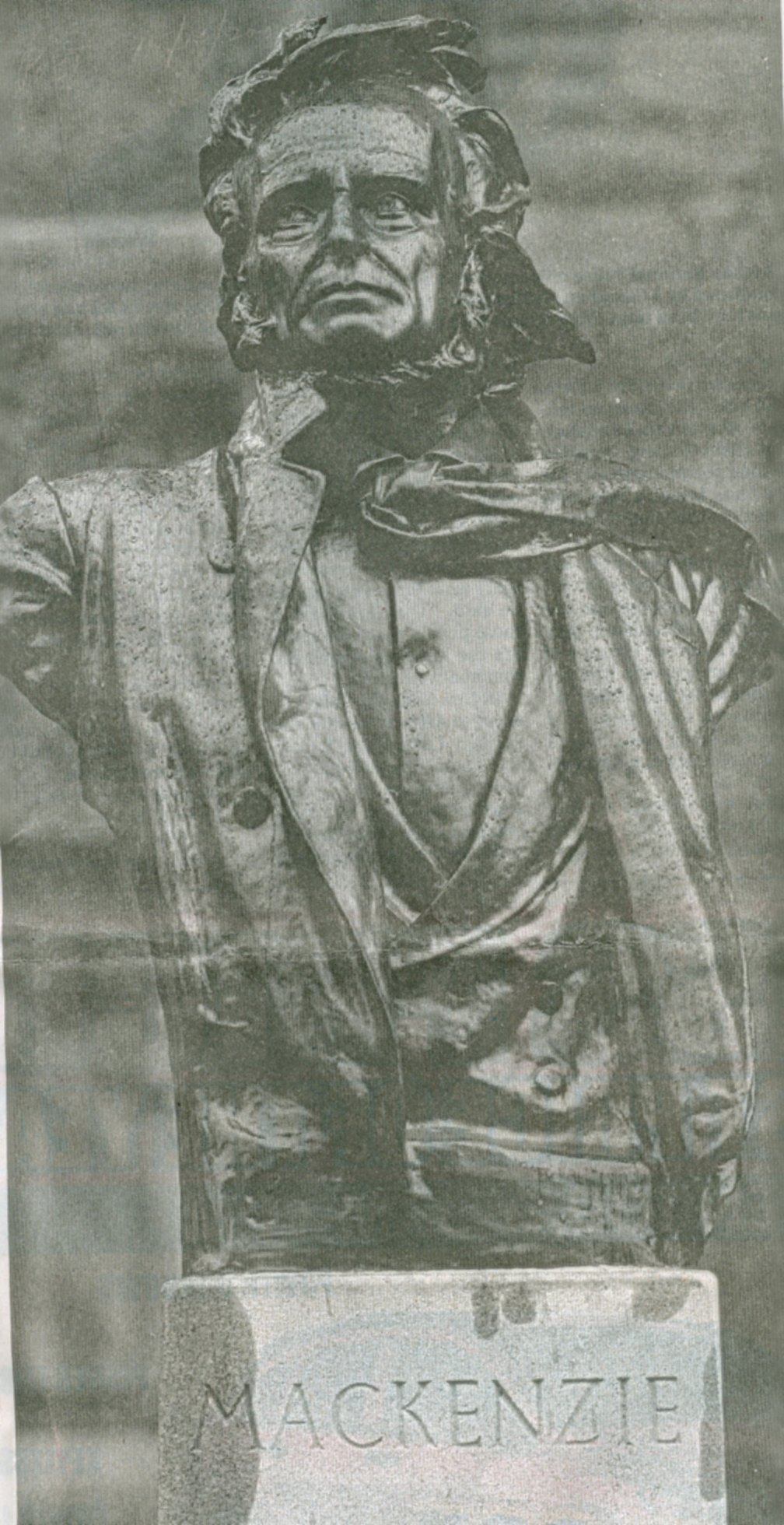

Statue of William Lyon Mackenzie at Queen's Park by Walter Allward, creator of our Vimy Memorial. |

The new Lieutenant Governor of Ontario, David Onley, who was appointed to that position in July, 2007, was taken on a tour of the Legislature grounds by an historian to learn about the statues and markers that adorn the grounds of Queen's Park. He was disappointed to discover that a statue of William Lyon Mackenzie created by Walter Allward, was hidden away in the shade on the west side of the Ontario Legislature. Given the great contribution Mackenzie made to our fight for responsible government, he believes Mac deserves a more prominent placement and has decided to seek his statue's relocation. Any decision to make such a move is the responsibility of the Speaker of the Legislature and it remains to be seen what he will.agree to have done.

It is ironic that the Lieutenant Governor, the hated office holder who was Mac's main nemisis back in the 1820s and 1830s, would want to draw greater public attention and respect to the Little Rebel, whose newspaper, the Colonel Advocate, so badgered and bedevilled the holders of that office back then, that one of them, Sir Franceis Bond Head, would happily have had him hanged if he had been able to catch him. . .Copyright © 2013 Website Administrator