foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

SIMCOE & HIS NEMESIS DORCHESTER

History deals with individuals as social beings.

|

|

Lord Dorchester & John Graves Simcoe |

The names of John Graves Simcoe and Sir Guy Carleton, 1st Baron Dorchester are writ large in the early history of Niagara and our nation. Unfortunately during the four years they simultaneously served their sovereign in Canada, dissension and discord poisoned their personal relationship.

Simcoe, who was in his 40th year with exuberant energy, was an idealist whose dreams had not yet been shattered by time. Dorchester in the evening of his life was a very practical individual whose experience confirmed his deep distrust of visionaries. Both were proud men of inflexible character. Simcoe was set on running his own show in Upper Canada. Dorchester, who insisted on deference from his inferiors, was just as determined to assert centralized authority. In pursuit of this objective he regularly reined in his determined and stubborn young subordinate.

Carleton came to Canada in 1759 as quartermaster general at General James Wolfe's request. He was wounded leading a regiment of grenadiers at the Battle of the Plains of Abraham, wounded again during a military campaign in Europe and wounded a third time at the siege of Havana. Carleton served as lieutenant governor and governor of Quebec from 1766 until 1770. He returned to England for four years during which time he was heavily involved with the drafting of the Quebec Act which was passed in 1774. Carleton returned to Quebec in 1775 where he proved to be more than a match for the invading American rebels. His cunning, courage and energy inspired his men to drive back the Americans from Quebec City's citadel and eventually save the country. Sir Guy returned to England in 1778, but four years later was recalled to duty commander-in-chief of British forces which oversaw the withdrawal from New York of some 30,000 British troops and some 27,000 Loyalist refugees. This latter number included several thousand former black slaves, who despite George Washington's vehement protests, were helped to flee from the 13 Colonies to the Caribbean and to Nova Scotia.

|

|

Sir Guy Carleton/Lord Dorchester |

Sir Guy Carleton was honoured for services to the sovereign and awarded the title Lord Dorchester. When he came back to Canada as governor general in 1786, it was a different and more demanding country to which he returned. Nonetheless, Lord Dorchester's reception in Quebec was a warm one for his reputation had been enhanced by his absence and by comparison with leaders who had replaced him.Dorchester was to retain this position, which included responsibility for Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island as well as Canada, until his retirement in 1796. His association with Canada spanned 37 years. "One of the most distant, reserved men in the world," the stiff, stubborn, incorruptible Dorchester laboured to make Canada a loyal part of Britain's empire, while firmly rejecting Prime Minister Pitt's plan to establish a Canadian aristocracy. He always opposed both the concept of high-sounding hereditary rank among colonials and making membership in the legislative council hereditary. Instead of titles Dorchester proposed a kind of nobility in name when he designated the American emigres United Empire Loyalists, and gave these reluctant immigrants the right to affix the letters U.E. to their names.

John Graves Simcoe served as lieutenant governor of Upper Canada from 1792 until 1796. On the 12th day of September, 1791, Simcoe received the following communication.

To Our Trusty and Well-Beloved John Graves Simcoe, Esquire,Greeting:

We, reposing especial trust and confidence in your loyalty, integrity and ability, do by these presents constitute and appoint you to be Our Lieutenant-Governor of Our Province of Upper Canada in America. To have, hold, exercise and enjoy the said place and office during our Pleasure, with all rights, privileges, profits, perquisites and advantages to the same belonging and appertaining, and further in case of his death or during the absence of our Captain-General and Governor-in-Chief of our said Province of Upper Canada, now and for the time being We do hereby authorize and require you to exercise and perform all and singular the powers and directions containing in Our Commission to Our said Captain-General and Governor-in-Chief, according to such Instructions as he has already received from US, and such further Orders and Instructions as he or you shall hereafter receive from US, and we do hereby command all and singular Our Officers, Ministers and loving subjects in Our said Province, and all others whom it may concern, to take due notice hereof and to give their ready obedience accordingly.

Given at Our Court of St. James in the thirty-first year of Our Reign.

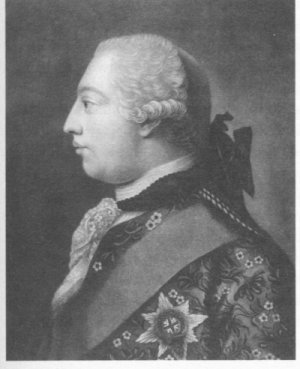

By His Majesty George III's Command

|

|

George III |

As military man and governor general of British North America, Lord Dorchester was at the top of of the hierarchy, and fully expected that Colonel Simcoe would respect his place in it as Dorchester's subordinate. Simcoe seems to have been under the misapprehension that as lieutenant governor of Upper Canada, he would be supreme in that province. He grudgingly recognized Dorchester's overall authority in BNA, but presumed his judgement regarding military matters within Upper Canada would take precedence. He quickly discovered otherwise, when his recommendations regarding the establishment of fortified posts in Upper Canada as a means of promoting settlement were simply ignored. Dorchester was insistent that available forces be concentrated largely in Lower Canada, which he considered the heart of the country. He believed Simcoe's policy would not only sap important military resources, but that it would also reduce self-reliance in the settlers.

Thus the two men shared power and antipathy. Lord Dorchester was Simcoe's superior and the bane of his existence. Simcoe was Dorchester's subordinate and the source of frequent frustrations. Simcoe regularly attempted to circumvent Dorchester's authority by appealing over his head to the home authorities. Dorchester bristled at this insubordination and consistently overruled Simcoe's plans for his "precious province." Authorities in London exacerbated the situation by refusing either to censure Simcoe for failing to observe the chain of command, or to delineate more clearly their areas of responsibility.

The enmity between the two men began before they ever met. In 1782, an order had been issued for the promotion of officers of Simcoe's regiment, the Queen's Rangers, but through the interference of Dorchester, it had not been executed. In addition, Dorchester had recommended Sir John Johnson, the Superintendent of Indian Affairs, as "the properest person" for Upper Canada's top job. When his nominee was rejected, an indignant Dorchester took out his anger on the government's choice - John Graves Simcoe. Simcoe was warned by a friend before he took up his new task that "the only embarrassment I conceive you likely to meet with will be from Lord Dorchester." This proved to be an accurate prediction. Dorchester rarely accorded Simcoe any support in his position as lieutenant governor and the sensitive and zealous Simcoe resented any restraint on his powers, particularly from the man who had opposed his appointment.

In letters of exhaustive length dispatched from Navy Hall, a frustrated and embittered Simcoe protested that his reasonable hopes and aspirations for his precious province were being "blighted and destroyed" by Dorchester. One example of this was Simcoe's selection of London on the Thames as the colony's capital, a choice that was quickly vetoed by Dorchester. Another of Simcoe's priorities was roads through the sylvan solitude, chief weapons in the military and political life of the colony. These primeval trackways, which were to be constructed by skilled surveyors and indefatigable soldiers, were to run from fort to fort. Despite the fact that they were critical for the economic and social life of the new land, Simcoe's plea for more troops was icily ignored by his superior in Quebec. Simcoe's proposal to fortify York was also rejected. Simcoe complained sarcastically to London that >"His Lordship does not honour me with his reasons." Tensions between the two officials grew as each complained to the Colonial Office that the other was seeking to restrict or usurp his authority. Had officials at the Colonial Office clearly delineated their spheres of authority and then enforced adherence to them the effectiveness of the two men might have been improved and their services extended.

Early in 1794 things began to look ominous. General Anthony Wayne was in command of an army raised to drive Indians out of parts of the Ohio territory. During this time of mounting tensions between Britain, an ally of the Indians, and the United States, Dorchester added to the edginess in a speech to a number of Sachems warning them of the liklihood of war with the United States. This was picked up the American newspapers and reached the attention of the American secretary of state, John Randolf, who declared it "hostility itself." The flames were further fanned by Dorchester, who fearing an attack by on Detroit by Wayne, directed Simcoe to rebuild Fort Miami which was located on American soil. Rumour had it that Wayne following his defeat of the Natives intended to attack British posts in American-held territory and then invade Canada.

|

Simcoe was astonished at Dorchester's order and wondered at its wisdom. He delayed implementing action for as long as he could but was finally forced to comply. When the crisis between the two countries passed, both men were chided by the Colonial Office for nearly precipitating a war by re-building the fort. Simcoe defended his actions by stating he was only following orders.

Dorchester was outraged by this reprimand from London and haughtily resigned in a huff. In a letter to Dundas, Dorchester wrote, "You will perceive, sir, with me, that various reasons concur to make it necessary for the King's service that I retire from this command. I am, therefore, to request that you will have the goodness to obtain for me His Majesty's permission to resign the command of his Province in North America and that I may return home by the first opportunity."

The two men were temperamentally incompatible. Described at various times as severe, cold and complacent with a streak of meanness, Dorchester relished authority and his own importance. He was careful to cover his tracks. His official correspondence is often contradictory, reflecting his determination to produce the desired ambiguous effect. To ensure that history did not hound him he ordered his wife to burn his personal papers when he died which she did.

|

Simcoe was stubborn and driven by a sense of mission that became a mania. Because he could neither work with Dorchester nor implement his many plans for the province, his service in Upper Canada was a series of unfailing frustrations. He wore himself out attempting to accomplish what he could not. Finally ill, disappointed and disillusioned, Simcoe sought surcease in a leave of absence from his dream province to which he never returned. Immediately prior to his departure Simcoe unleashed a pen filled with the bitter ink of indignation and exasperation. In a letter he wrote upon leaving Upper Canada because of "the rapid decline of my health," an embittered Simcoe declared his disappointment at Dorchester's incessant interference with his "ardent zeal and desire to execute with industry and vigour" great public measures.

In His Own Words"I now perceive all my reasonable Hopes & views are blighted and destroyed. Had I known that all my measures were to be checked, counteracted, and ultimately annihilated in consequence of your Lordship's opinion, I would not have accepted the appointment to which His Majesty had been pleased to appoint me."

In his reply to this frustrated and fervent outburst, Dorchester's response was what must have been to Simcoe a maddeningly mild and imperturbable rejoinder. "I am much concerned to hear of the ill state of your health."

In his own lengthy resignation to officials in London written in November, 1795, an outraged Dorchester, also embittered by what he considered the meddlesome and missplaced intervention of bureaucrats far removed from the scene of action, complained in a resentful and somewhat overwrought declaration.

In His Own Words"All command, civil and military being thus disorganized and without remedy, your Grace will, I hope, excuse my anxiety for the arrival of my successor who may have authority sufficient to restore order lest these insubordinations should extend to mutiny among the troops and sedition among the people."

|

The end of an era was reached in 1796 for Dorchester and for Simcoe, both of whom left Canada that summer. Even their leaving was linked by contention. Dorchester sailed from Quebec on July 9th on the vessel Active which ran aground on July 15th on the rocky shore off the coast of Anticosti and could not be freed. Later that same month when Simcoe arrived at Quebec he was agitated to learn that the ship, Pearl which had been designated to transport him and his family home was at sea. He mistakenly believed it had been dispatched to rescue Dorchester and others at Perce and then proceed directly to England thereby delaying Simcoe's departure. In fact, that was not the case since another ship had been dispatched from Halifax and it returned Dorchester to England at the end of September exactly 30 years after he had first come to Canada. The Pearl finally arrived at Quebec on the sixth of September and on Monday September 10th the Simcoes sailed for England.

|

|

HMS Frigate Pearl |

No governors before or since Lord Durham had created such an impact as Dorchester. For thirty years he had moulded the country during its formative period. In four short years Simcoe nursed the new province into existence and succeeded in shaping Upper Canada with a mixture of loyalty, conservatism and economic activity that dominated the province for years to come. One wonders what their legacies in the service of the sovereign might have been if the two men had been friends rather than adversaries. In any case all the vigor and the vision departed with them for their successors were lesser men, aloof, haughty, arrogant exiles in an isolated colonial outpost content simply to serve their sovereign and earn his approbation rather than act in the interests of the Canadian colonies.

Copyright © 2013 Website Administrator