foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

SIMCOE & THE AMERICAN COMMISSIONERS 1793

History invites us to visualize dinners, dances, discussions - daily life.

|

|

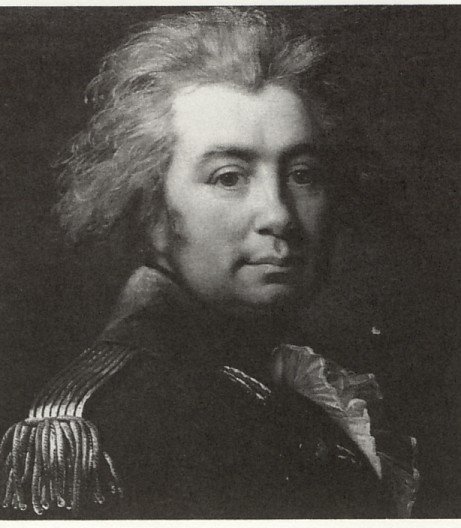

John Graves Simcoe |

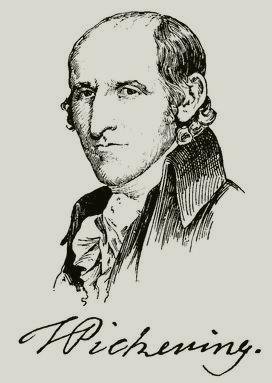

"You may be sure I was glad to be ridden of the commissioners after six weeks of their company." So wrote Simcoe on July 26th, 1793 following the departure from his home at Navy Hall in Newark of three American officials: General Lincoln, Colonel Randolf and Colonel Timothy Pickering.

|

|

Colonel Timothy Pickering |

The three men had been appointed by the American Congress in the spring of 1793 to meet with a council of Western Indians to discuss establishing a boundary line on the western frontier which would separate United States territory and Aboriginal lands. It was hoped this meeting would finally bring peace to the frontier. Simcoe offered to facilitate the process by hosting the commissioners until the meeting took place, hence their presence at his home for six weeks.

While Simcoe was pleased to see the last of the Americans, his wife, Elizabeth, was overjoyed because she had been "extremely inconvenienced" by these men in the midst of their modest dwelling. At times during their extended stay, she and the children were forced to find accommodation in the homes of friends and her absence on those occasions did not go unnoticed by the commissioners, who suspected it was due to their disproportionate presence in the house. They offered to encamp elsewhere, but according to the Americans, Simcoe "barred their removal because of his politeness and the hospitality of which he has a large share."

|

|

Portrait of Elizabeth Simcoe by Mary Anne Burges |

While he was most gracious towards his American guests, Simcoe was not the least enthralled with Messrs. Lincoln, Randolf and Pickering, whom he later described respectively as "civil," "able and rakish," and "a violent, base, philosophic, cunning New Englander." Simcoe thought they exhibited,

In His Own Words"much of that low craft held for wisdom by the self-opinionated people of the United States."

|

During conversations at the dinner table, the Americans endeavoured to convince Robert Hamilton and Richard Cartwright - Canadian gentry whom Simcoe described as being "of the same stamp" as the Americans - that states matured just as children grew into adulthood and when they did, "they set up for themselves." This explained their country's passionate pursuit of independence from Britain.

|

During their six-week sojourn with the Simcoes, the three foreigners showed a keen interest in the activities occurring in the British settlement. One kept a detailed account of life in the little colony and his diary included a description of the celebration of George III's birthday on June 4th, which was observed with fireworks, fun and a great show of loyalty.

|

It was also the day of the annual mustering of the militia. Untrained and undisciplined, its members were put through their paces by a retired officer of the line. Militia dress was varied. Few had uniforms and fewer still had fire-arms. Most of the men carried a weird variety of weaponry, including such things as sticks, brooms, pitchforks and pikes. After executing a few left turns, right turns and "dress with eyes front," the sovereign was saluted with a feu de joie, followed by a rousing if somewhat raucous version of God Save the King. After martial manoeuvres, all adjourned to the canteen for refreshments, frolic and usually a few fights.

|

At eleven o'clock on June 4th the governor held a levee at Navy Hall. At one p.m. troops in the garrison and those at Queenston fired three volleys and ran the royal standard up the flag pole, following which field pieces and garrison guns roared a royal salute. That evening there was a ball in the council chambers, where scarlet-coated officers whirled women in colourful gowns, some eighty people dancing from seven to eleven. It was noted by the American commissioner that some twenty of those present were "well-dressed, handsome ladies," who met each other with "ease and affection." The music and dancing were thought to be good and the meal which followed was considered to be "in pretty taste." The commissioner noted that Simcoe made a point of speaking with each and every one in attendance "to make their station in the infant province as flattering as possible." Simcoe told the Americans he thought public assemblies were important for morale, and that during the winter he intended to have concerts and assemblies frequently.

|

One day the commissioners travelled as far as the Falls, noting as they rode along a road which they described as "bad," the number of new settlements on flat land covered largely with white oak trees. The next day heavy rains prevented travel and the following day was excessively hot. On July 2nd they proceeded to Fort Erie where they stayed with the commanding officer. They admired his garden from which they ate cherries and currants. The potatoes were in blossom as were cucumbers and melons. Indian beans were ready to be eaten as stringed beans. They dined on peas, beans and new potatoes "as big as eggs," the latter having been planted about the middle of April. The commissioner said he noted these things solely to show the "state of vegetation in this climate" on the 2nd of July.

|

The American government was growing increasingly incensed with the western Native tribes because of raids they were making on small American settlements illegally located on Aboriginal land. Instead of finding fault with American frontiersmen who persisted in encroaching on Aboriginal lands, Congress blamed Britain for inflaming and funding the fighting by Natives north and west of the Ohio River. Simcoe vigorously denied this, but he feared war with the United States was inevitable and imminent. On February 1st, 1793 France declared war on England, and it was no secret that American sympathies lay with the French Republic. With most of the British military fighting French forces in Europe, what better time to attack Britain and break its hold forever on Canada. Pressures were mounting on President Washington to abandon his policy of neutrality and cleanse the continent once and for all of what Thomas Jefferson called "that harlot England."

|

The Aborigines said that the Americans were "multiplying like rattlesnakes" and their insatiable lust for new land led to their steady migration westward, where they proceeded to stake their claims in the fertile fields of the Ohio River country, land which the Aborigines had said was inviolate. With scant regard for Native land claims or their way of life, American colonists edged ever westward. Indian superintendents and British military men complained of the Americans' fraudulent land purchases, their abuse of the Aborigines and the absolute disdain displayed by American interlopers for the treaties signed by their own government. Finally the western tribes decided the whiteman would force them no further and they formed a fragile federation resolved to repel the intruders by attacking the fledgling settlements west of the river. Settlers continued to come, however, in ever-increasing numbers, spilling over into Native lands, and then demanding that the government protect them from Aboriginal braves attempting to defend their land.

|

One of the American commissioners was a congressman, and he frankly admitted that accusations that the British were secretly arming the Native tribes were "mere surmise and suspicion." The real reason for the raids, he frankly stated,

In His Own Words

"was the thirst of the American settlers for evermore territory. This insatiable lust for land has driven these sons of Nature to desperation."

In a final attempt to purchase peace, Congress had dispatched the three commissioners to "treat" with the Natives at Sandusky, Ohio. Joseph Brant, the great Thayendanegea, chief of the Six Nations Tribes was counselling his Western brothers in their dealings with the Americans. He hoped

, In His Own Words"they would soon establish a peace agreeable to all parties under the direction of the Great Spirit."

Brant explained his own support of the British. "Every man of us thought that by fighting for the king we should ensure to ourselves and children a good inheritance. While the British lost the war with the Americans and failed to provide in the peace treaty any provision for the Aboriginals who had fought along side them, they did keep the faith and compensate their Native allies by granting a large piece of land to Brant and his Six Nations along the Grand River.

w |

|

Joseph Brant |

The American government requested Simcoe's assistance to get their commissioners safely to and from the meeting place in Ohio and he readily agreed. While Simcoe secretly shared the Aborigines' hope of halting the westward expansion of the Americans, he realized that if war came between them Britain would likely lose the western posts its troops were still occupying at Michilimackinac, Detroit, Niagara and Oswego. The loss of Niagara, he believed, would ultimately lead to the loss of Canada. For this reason he was honestly anxious to help resolve the impasse. His assistance included provisions for the sustenance of the Natives during their negotiations with the Americans which included: Indian Corn - 1500 Bushels Pork - 100 Barrels Flour - 100 Casks Pease - 10 Barrels Bullocks - 20

A preliminary meeting of fifty sachems and the three American commissioners took place at Navy Hall with Simcoe in attendance. There was a great deal of talk by the Aboriginal chiefs about using the Ohio River as a boundary line between the two parties. The Americans listened in silence knowing full well that their nation was not prepared to accept such as boundary. For this reason it was suggested the parties adjourn to Sandusky at the west end of Lake Erie for the full Council meeting. Simcoe had previously been invited by the Native sachems to attend the meeting as a mediator and representative of His Majesty because Britain was the principal party in the various treaties that had been concluded with the Natives after the year 1763 and before the American revolution.

The chiefs now renewed their invitation to Simcoe to accompany them. Despite having being told by London earlier that it might "be of material advantage to His Majesty's interests to do so," Simcoe declined the invitation, diplomatically declaring as the American commissioners looked on silently that the invitation was not unanimous. The Americans had earlier stated that Britain's mediation would serve only to diminish the importance of the United States in the eyes of the Native chiefs and might very well lead to disagreements between the two countries. The chiefs asked Simcoe to supply them with all the maps, charts and treaties pertaining to the area since they had nothing in writing "to assert our just claims." Simcoe delegated two Indian superintendents to accompany the Aborigines and provide them with every support. In the event that talks between the parties broke down, Simcoe warned the superintendents to ensure that no injury befell the American commissioners for it was widely feared that if "talks failed there could be fighting."

Simcoe believed the talks would fail and felt the Americans were meeting simply as a "necessary precursor to the destruction of the Indians." President Washington had described the upcoming meeting as "being of great moment to the interests and peace of this country" and directed the commissioners to "be well informed and clearly instructed on all points likely to be discussed."

Nevertheless he expected little of the meeting. In His Own Words"While I feel inexpressible pain at the distressing accounts from the western frontiers occasioned by Indian hostilities, little if any thing can be expected from the proposed negotiation of peace with the hostile tribes to be assembled at Sandusky. However, it was important for the good people of these States to see that the executive has left nothing unessayed to accomplish peace. If the sword is to decide then the arm of government would be enabled to strike home."

|

|

Aboriginals Attack To Forestall American Settlements |

Prior to taking leave of Simcoe, the Americans were told by a Mohawk Native from the Grand River that Simcoe had "advised the Indians to make peace but not to give up any of their lands." When the commissioners informed Simcoe of this he did not deny it but replied, "It is of that nature that it cannot be true since the Indians had not applied for his advice on the subject." He did inform them that "ever since the conquest of Canada it had been the principle of the British governemt to unite the American Indians." The commissioners found this statement "ominous of ulterior designs."

On July 14th the commissioners and their suite of 12 persons embarked from Fort Erie on His Majesty's schooner Dunmore under Captain Ford.

|

They arrived at the west end of Lake Erie on July 21st, but were denied permission to travel to Fort Detroit which was then a British garrison, so they set up their camp at the mouth of the Detroit River. Meanwhile the Council of Native chiefs and warriors had assembled at the foot of the Miamis Rapids. After having waited impatiently at their camp for 12 days, the commissioners were shocked and surprised to learn that they were not to proceed to the great Native assembly at Miami Rapids at all, Instead they were to submit their proposals in writing which would then be taken by Native runners to the Aboriginal Council. The Americans were vigorously opposed to using the Ohio River as a boundary and fully intended one way or the other to occupy Native land on the west side of the river. The bottom line of their written proposal to the chiefs was an offer to purchase Aboriginal lands on the west side of the Ohio River on which white settlers had already squatted.

Two Wyandot runners finally returned to the commissioners with the Council's written reply. To the commissioners' surprise, the Natives rejected the offer to buy out their birthright. They proposed instead that the Americans use the money to re-locate the American squatters back to the "whiteman's side of the Ohio," that is, the east side. The sachems were insisting that the Ohio River should serve as the boundary between Aboriginal and American territory.

In their letter to the commissioners they stated, In Their Own Words"Brothers; - The Deputies we sent to you did not fully explain our meaning; we have therefore sent others to meet you once more, that you may fully understand the great question we have to ask you and to which we expect an explicit answer in writing. Brothers: - You are sent here by the United States in order to make peace with us, the Confederate Indians. Brothers; - You know very well the Boundary line which was run between the White People and us at the Treaty of Fort Stanwix was the Ohio River. Brothers; - If you seriously design to make a lasting and firm Peace you will immediately remove all your People from our side of the River. Brothers; - We, therefore, ask you are you fully authorized by the United States to continue and firmly fix on the Ohio River as the Boundary line between your People and ours? DONE in General Council at the Foot of the Miamis Rapids, 27th July 1793. In behalf of ourselves and the whole Confederacy and agreed to in a full Council."

Signed Indian Nations : Wyandots Bear Delawares Turtle Shawanese Snake Miamies Turtle Mingoes Snipe Poutawatamies Black cat Ottawas Sturgeon Connoys Turkey Chippawas Crow Muncies Turkey

The determination of all Natives, even those friendly towards the Americans, regarding the boundary between the two peoples was the Ohio River. Chief Cornplanter gave the following toast when he met with General Anthony Wayne at a place called Legionville in the spring of 1793. "My mind is upon that river," he said, pointing to the Ohio. "May that water ever continue to run and remain the boundary of lasting peace between the Americans and Indians on the opposity shore."

The American commissioners angrily dismissed this offer out of hand declaring that should the Natives persist in such demands then negotiations were at an end. Since the Native chiefs were unyielding about the Ohio River as the boundary, it became apparent that war not words was to settle the frontier and the fate of the Western Natives. The American commissioners had earlier rejected the Ohio River as the boundary line and they indicated the talks were at an end. They decided on returning "with the first fair wind to Fort Erie," and embarked on August 17th, arriving back at Fort Erie on August 21st, whence they returned to Philadelphia. The September 7th issue of The Philadelphia Gazette reported that by insisting on the Ohio River as a boundary, the Natives showed their determination for war. It was evident to the Americans that the might of arms must make a final settlement of the matter and to arms they prepared to move.

Captain Johnny, a Shawnee chief who was present at the pow-wow, sadly reported to Simcoe that the talks had failed.

In His Own Words"The Americans have insisted on keeping possession of almost our whole country and in return offering us money in repayment which is useless to us. We have proposed peace and they have not consented to our proposal. The fault is not ours. We expect now to be forced again to defend ourselves and our country. We depend on nothing so certainly as your protection and friendship." You may be assured, said Captain Johnny to a saddened Simcoe, "that never before have we stood in such need of both." Even as he listened to the chief's lament, Simcoe knew Britain would do nothing to aid her "old allies and firm friends." The horrors of war now lay before them.

On September 20th, 1793 Simcoe reported in a coded message to London that there was universal apprehension in the settlement over expected hostilities between the Natives and the United States. When the conflict came, he expected it would engulf the colony. If the United States did invade Canada, Simcoe doubted there would be much local opposition. Many of the poor, dispirited Loyalist settlers had already suffered severely for their earlier loyalty to the crown, and were "more apt to regret what they have lost than remember what they have received." It is my duty to observe, wrote Simcoe, "that no Recruits can be raised in this Province because the price of labour is so high." No one would leave their civilian jobs to serve and suffer for less pay as a soldier.

Frequent fighting followed between the Americans and the Natives, and initially in these skirmishes the Aboriginal warriors defeated the American troops. The tide turned on August 20th, 1794 when the American General "Mad Anthony" Wayne met the combined Native tribes at the Battle of Fallen Timbers near Toledo. Under cover of fire by sharpshooters and a charge by sabre-swinging dragoons, the well-drilled American infantry made a bayonet charge into the fallen timbers. It was all over in forty minutes. This victory opened the floodgates and American settlers poured across the Ohio River. The whiteman had come to stay.

Copyright © 2013 Website Administrator