History is the witness that testifies to the passing of time.

A nation's past assures its future. The French meaning of the word 'nation' comes closer to the Latin original, whose root is the verb 'nascor' to be born. A nation is a group of people who are born of common ancestors. English use of the word nation, stresses the idea of political sovereignty, but does not place as much emphasis on the idea of blood, that is, descent or race. In the United States, for example, there in no sense of a blood group, but unquestionably it exists as a nation. A nation is a community of people, especially a community that is politically independent, occupying and possessing a defined territory.

Thus environment also moulds a nation. Talk of separating cannot divide the St. Lawrence river from Lake Ontario. They are part of one great highway leading into the heart of Canada. Whether they like it or not, geography forces some kind of unity of the people living within it.

What is a nation? Two definitions of 'nation' are pertinent to this narrative. (1) A nation is a community of people occupying and possessing a defined territory and united under one governnment, especialy a community that is politically independent. (2) A nation is a people having the same descent and social and political history and usually sharing a common language.

Can a country comprise two nations? Both French and English contribute to the challenge of this great country called Canada.

Should Quebec be called a nation? Separatists in Quebec believe that Quebec should declare its independence and become a nation as defined by Number One. Others believe that Quebec is a nation as defined in Number Two.

Whether Quebec is or is not a nation continues to preoccupy Canadians into the 21st century because of a decision made late in the 18th century by Great Britain's Imperial Parliament, the name of the British Parliament when it dealt with colonial matters. An Act passed by the Imperial Parliament two hundred and thirty-two years ago has made this a matter of contention and dissension down to the present day.

Following the din of battle on the Plains of Abraham, new days dawned for the British Empire and the North American continent. The citadel of Quebec had fallen, but the conquest of Canada had just begun.In 1759 as a result of Wolfe's victory on the Plains of Abraham, Westminster began to wonder what to do with this large, foreign land. While the question was being pondered, many different kinds of people came to this new colony. English-speaking merchants and settlers flowed in from both Britain and the American colonies. Before long they began to agitate for the rights of all Englishmen. Melding the mix of different people into a new nation was a problem which a century and a half has not solved.

|

|

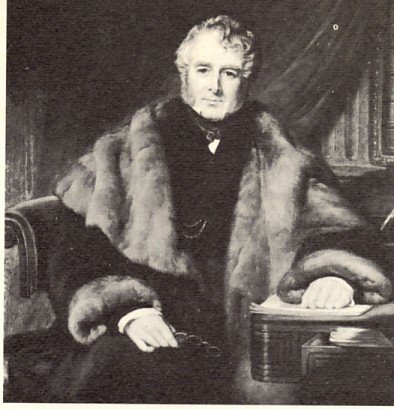

James Murray |

The first British Governor, James Murray, favoured the French Canadian seigneurs and considered the demanding and often critical English-speaking merchants "the most cruel, ignorant, rapacious fanatics who ever existed." Merchants in turn considered Murray a despot and condemned him for his strict controls on the fur trade. They denounced him as being too conciliatory to the French-speaking population, which represented 95 per cent of the population and petitioned the king for his recall. In 1766 Murray returned to England and despite having successfully defended himself against all charges, never returned to Quebec. Murray was replaced by Sir Guy Carleton, who before long like Murray, began to favour the compliant, French-speaking population and oppose the troublesome English merchants with their constant complaints and carping demands.

|

|

Sir Guy Carleton |

Ongoing pressures from the English merchants in Quebec for the same liberties and laws that existed in the Thirteen Colonies convinced British government officials to make changes in the administrative structures of the colony. This resulted in the Quebec Act of 1774 finally passed on the 18th of June by the House of Lords. This first Imperial statute endeavoured to create a constitution for a British colony that would copy with the complexity of relations between the two groups of people comprising what became Canada. The Imperial Parliament did so almost exclusively on the recommendations of Quebec's English governor, Sir Guy Carleton and over the vehement objections of the small group of English merchants living in Quebec.

Historians have long questioned whether this enactment would have been better for both Quebec and the future of Canada if its framers had attempted to commence the process of bringing about the assimilation of French-speaking Canadians into an Anglo-Saxon majority. Lord Carleton firmly believed this would never happen. He said he saw no likelihood of these Canadians ever becoming assimilated into a majority of English-speaking immigrants. The existing "superiority of the French Canadians would never diminish," since there would be few immigrants going to the new world who would ever "prefer the long, inhospitable winters of Quebec" to the enticements of the sun and the south. However, although the colony was cold and barren, Canada was, Carleton said, healthful and for this reason the French would multiply and to the "end of time the country would be peopled by the Canadian race."

While it may never have been possible to completely assimilate French Canadians into an English-speaking Canada, future co-operation between the two language groups was made more difficult by this Act which increased the French feeling of separateness. Under the Act Quebec received benevolent authoritarian rule which essentially drastically reversed earlier legislative provisions designed to create uniformity in the English colonial governments of North America. While the Act was made with good intentions, this key piece of legislation was both criticized and acclaimed from the moment it appeared.

The Quebec Act of 1774, called the Magna Carta of the French Canadian race, was praised as just and humane since it confirmed to Canadians the free use of their language, their customs and their Roman Catholic religion. It granted them most of the old French property and civil law while implementing the more humane English criminal law. It continued seigneurial tenure of land. It ensured the rights of the clergy to collect tithes and offered the people an oath of allegiance that contained no insulting religious clause. It substantially maintained the traditions of the French regime which included:

(a) rule by the governor and appointed council;

(b) the primacy of the church;

(c) the retention of the privileges of the seigneurs and feudal land tenure.

In addition the Act expanded the new province of Quebec to include land previously annexed to Newfoundland, much of what is now Ontario and all the western lands between the Ohio River and the Great Lakes as far as the Mississippi which represents what became the American states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan and Wisconsin. These latter lands were coveted and claimed by the 13 Colonies and the incorporation of them by the Act into the new, greatly enlarged territory of Quebec enraged Americans and was a contributing factor to the revolutionary war the Americans eventually won and subsequently opened the west to a surge of settlers.

There was great satisfaction among the seigneurs and the clergy and British government supporters in England and in Canada thought it the best solution to a very difficult problem. Parliamentary opposition in England, nearly everyone in the American colonies and the great majority of English-speaking people in Newfoundland, the Maritime provinces and Canada itself were dead set against the Act.

Carleton opposed colonial legislatures and so the matter of an elected assembly was set aside. In his letter to the British government dated January 20, 1768, Carleton said:

In His Own Words:

It was difficult to know just what the majority of Canadians actually felt about an assembly. Few could read and the majority had no knowledge whatsoever of democracy, so it was easy to claim they were uninterested in adopting a democratic system. They had always been ruled by a king's deputy and his little court and as long as this rule was light they preferred it. When it was replaced by a governor and council appointed by the British crown they accepted it. Carleton said that the British form of parliamentary government transplanted to Quebec would never produce "the same Fruits as at Home," since it was impossible for the "dignity of the Throne or Peerage" to function in the backwoods and the bush. Because the governor would have little or nothing to give away and so would have less influence, Carleton felt it was critical that the governor not share power with the people.

During the House of Commons debate the refusal by the government to grant the colony an assembly was a most contentious issue. Distinguished parliamentarians like Edmund Burke and William Pitt as well as the English merchants and settlers in Quebec pleaded passionatley for what they said was a basic right of all Englishmen.

|

|

Edmund Burke |

|

|

William Pitt |

It was all to no avail. Carleton considered Quebec's English settlers whiny, difficult, trouble-makers and esteemed the more amiable and obliging French-speaking Quebecers and so successfully fought for their right to remain under an benign oligarchy.

|

|

Jean Charest, Premier of Quebec (on the left) |

The terms of the Act were considered a matter of simple justice to the Canadians. Quebec's present Premier, Jean Charest, agrees and has recently lavishly lauded the Quebec Act. Others maintain "that the seeds then sown have flowered ever since like stubborn weeds." It is feared that the notion of a Quebec nation is a legacy of the Quebec Act which will ensure controversy and consternation for Canadians for many years to come.

1837 was the year of the Rebellions of Upper and Lower Canada.

When word of the rebellions in Upper and Lower Canada reached London, Prime Minister Lord Melbourne was exasperated by the recalcitrant colonies and seriously wondered at their worth. His government was weak and he was fearful the opposition would use the chaos in the colonies to bring it down.

|

|

Lord Melbourne, Prime Minister of Great Britain |

In addition Britain was euphoric at the accession of youthful Queen Victoria and the distant dissension came as an embarrassment to his weak government. Inclined to pursue whatever course of action promised the prospect of calm and leisure, Melbourne dispatched a dedicated liberal, Lord Durham, to seek a solution to the crisis in the Canadas.

|

|

Lord Durham |

As guns roared in salute and scarlet-coated soldiers stood rigidly at attention, Durham disembarked below the Citadel in May 1838. On a spirited white stallion and dressed in a magnificent uniform heavily embroidered with silver, the Lord High Commissioner made his ostentatious entry into the capital of Lower Canada. The cheering throngs had never seen a personage of such political prominence and social grandeur.

Lower Canada's rebellion resulted from worsening economic conditions, a bitter struggle to destroy entrenched political power and inflamed racial hostility. Armed rebellion had flared up in the Montreal region, but the badly organized and worse led Patriote forces were quickly crushed by British regulars and English Canadian militia. Some rebel leaders sought sanctuary in the United States. Twelve others were hanged and a number were transported to Van Dieman's Land. The English Canadians of Montreal protested at the too lenient treatment for traitors. French Canadians were silenced rather than satisfied. Their nationalism now had its martyrs.

Along with the High Commissioner's pomp came the trappings of power and Durham moved quickly to establish a policy of generosity. Charges were withdrawn against participants in the 1837 rebellion except for Papineau and a few other leaders who were warned not to return on pain of death. Eight rebels who had already been convicted were exiled to Bermuda. This latter act of leniency opened Durham to sharp attack in London which brought on one of his Byronic moods. He angrily resigned but not before completing his investigations and writing in ringing words his famous report.

Committees formed by Durham had been accumulating great amounts of material on all aspects of life in Lower Canada. With this material and his own observations he felt he was able to identify the problem that plagued the colony. The intensity of racial conflict seemed to him to be the most striking feature in the colony. In one celebrated passage Durham wrote, "I expected to find a contest between a government and a people; I found two nations warring in the bosom of a single state: I found a struggle not of principles but of races."

Durham believed the French Canadian society was static and destined because of its inward looking attitude to always be so. In Durham's mind the future of Quebec province lay with its English-speaking population and his Report made this plain. He believed British residents were sensitive to the currents of change in all its forms, while the French sector was entrenched in the ancient days and the olden ways.

In a hurtful phrase that gave bitter offence Durham described French Canadians as "a people with no history and no literature." He believed the only solution to the ethnic problem was the assimilation of the French group into the Anglo Saxon. The national character of their province must inevitably be that of the British race.

Union of the two provinces appeared to be the ideal solution to both its economic and racial political problems. Unification of the great St. Lawrence river valley would solve the former and union of Upper and Lower Canada would settle the latter. In the march of progress Durham envisioned for the province, French Canadians within the union were destined to fall by the wayside. Their dated nationalism would be overcome and they would be led gradually and naturally to abandon their separate ways and be absorbed peacefully into a wholly British Canada.

The English minority liked the idea of union. French Canadians were deeply hostile and personally wounded by the Report. Its impact was to strengthen their resolve to retain their language, their culture and their institutions.

The Imperial Parliament passed the Act of Union of 1840 creating a single province - the United Province of Canada comprising Upper Canada, renamed Canada West and Lower Canada, renamed Canada East. However, contrary to Durham's proposal, Parliament gave Canada East and Canada West equal representation in the new legislature, each to have forty-two members.

Durham had recommended that representation in the new legislature be based on population. He recognized that initially the French Canadian majority would result in their dominance in the legislature. He foresaw, however, that immigration from Britain would eventually reverse this and English Canadians would then permanently dominate the Assembly thus leading to the absorption of the French-speaking Canadians. Equality destroyed Durham's concept of a complete blending of the two peoples.

When as Durham predicted, English-speaking Canadians did eventually outnumber French-speaking Canadians, they insisted their larger population should translate into a majority in the Assembly. Not surprisingly French Canadians demanded that equality of representation be maintained. The frustrating failure of the English to achieve dominance in the legislature led to frequent stalmates and a growing sense of grievance in Canada West. In addition, if the possibility of absorbing the French Canadians by assimilation had ever had any chance of happening, it never occurred.

Over the years, the Quebecois national spirit has waned and waxed when some new spark stirred the smouldering embers. The latest delusional declaration by the Bloc leader compares Separatists in Quebec to members of the resistance in wartorn France occupied by the Nazis. The crazy outburst has been greeted with the contempt it deserves.

The Canadian Parliament has endorsed the latter position of those in Quebec who support nationhood and recently acted to declare Quebec a nation within the united country called Canada.This seeks to reconcile the races by declaring that the Quebecois form one of the founding nations in a united Canada - two concordant nations in the bosom of a single state. Shades of Lord Durham.

"Distortion is a necessary characteristic of all sources of information, since absolute objectivity is absolutely unobtainable."

Copyright © 2013 Website Administrator