foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

THE 49TH REGIMENT OF FOOT

History is an exciting ride through the past.

|

|

Flag of the British Army |

|

|

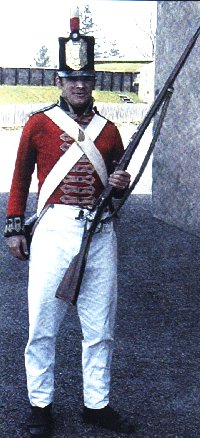

Captain 49th Regiment 1812 |

The British soldier's raison d'etre was the regiment. When he joined the army, he joined a regiment, which became his home, his family, his only source of support for the duration of his service. Military historians believe that men fought courageously first and foremost for their peers.

If the troops of the regiment were its life blood, then the colours were its heart, for they were the centre of resistance in battle. Colours originally were intended to help a soldier locate his own unit in the heat of battle, and the ritual of trooping the colours through the ranks of the regiment was intended to ensure soldiers knew what they looked like. Carried into action by the junior ensigns, the colours served as a rallying point if things went wrong. Colours were consecrated before being presented to the regiment by a member of the royal family or some other distinguished individual. They were regarded as the very soul of the regiment's honour.

|

|

Regimental Colours |

|

|

Regimental Colours |

In addition to being old and ragged from service, regimental colours frequently became badly damaged in battle because they formed a very obvious target and were regularly hit by projectiles. On accasion they were so badly worn, there scarce remained more than the poles. Nevertheless, even if cut to pieces and lying torn and tattered on a grief-stricken field, if the colours were not captured and the men fought stubbornly on, victory might still be theirs. There was something about the sight of a square piece of cloth tied to a wooden pole that stirred soldiers' hearts and motivated men to great deeds of heroism. It represented a kind of trophy which the regiment defied the enemy to capture. So long as the colours flew, military morale was boosted for the colours remained distinctive reminders of great deeds done. Proudly displayed on the regiment's colours were its battle honours which identified conflicts in which the regiment had excelled as a fighting force.

"A moth-eaten rag on a worm-eaten pole,

It does not look likely to stir a man's soul.

'Tis the deeds that were done 'neath the moth-eaten rag,

When the pole was a staff, and the rag was a flag."

|

|

Colours captured at Detroit (left) and Queenston Heights (right) |

The colours were entrusted to the most junior officer of the regiment. They were large and unweildy and difficult to carry. One 15-year old was blown over to the ground, colours and all, when a gust of wind caught the large sheet.

|

While young and often slight, the men defending the colours they carried is legendary. One soldier was pierced by a lance and despite the pain, he flung himself upon the colours and wrestled it away from an enemy soldier. Another received twenty-three sabre wounds, but clutched the colours to him with one hand and with sword in the other killed three of the enemy at the same time. He was sixteen years old.

Another sixteen year old courageously carried the regimental colour crying out "Rally on me men, I will be your pivot," as the enemy cavalry broke into his battalion. When called upon by French horsemen to give up his colours, he replied: " Only with my life," and he was at once cut down. He was "buried that night with all possible care." Sometimes when the colours were about to be taken, a soldier would rip it off the pole and fall on top of it. When one sixteen year old with just six weeks' service thought its capture was inevitable, he tore it off its staff and hid it in his jacket; it was found on his body in the evening.

The 49th Regiment of Foot, which was rich in battle honours, first came to Halifax 1776 in response to the "troubles in America." During the revolution the regiment fought with distinction. In 1778 the regiment departed for the West Indies, where it participated in the capture of St. Lucia from the French. Back in Europe once more, it served as a marine unit under Lieutenant-Colonel Isaac Brock at Copenhagen. When English county titles were adopted in 1782, the 49th became the Hertfordshire Regiment of Foot. The uniform of the 49th was scarlet with green facings and white, red and green lace. Its Light Company adopted the red feather rather than the green as a distinctive badge and Grenadiers were permitted to wear a black instead of a white plume.

|

A regiment was divided into two battalions each with ten companies numbering from 50 to 100 men in peacetime and up to 150 in wartime. One of the companies contained Grenadiers who were assault troops with 'grenades.' These soldiers, who were trained to carry and throw grenades, were equipped with a length of slow match with which to ignite their fuses. Since the grendades were weapons of assault the men who were trained to throw them had to be highly motivated risk-takers. Ideally they were also big and agile since length of arm and bodily strength contributed to the distance the grenade could be thrown. This resulted in grenadiers becoming elite soldiers who were dressed in ways reflective of their special status. A grenadier company of the tallest men took the right of the line; a light infantry company of the most active men took the left. These elite units of the battalion were sometimes separated to form special battalions placed at the forefront of any assault, their kneeling front rank presenting a hostile hedge of glinting bayonets.

In 1802 the 49th Regiment of Foot was ordered to Quebec where it arrived on 23rd of August. Travelling by bateaux the troops reached York the following July and in 1804 they took up garrison duties at Fort George. Rigorous training and discipline resulted in the fine reputation the British infantary had. Eleven separate steps were involved in the loading an firing of the .75 calibre Brown Bess. Countless hours were spent perfecting their battlefield drill and resulted in the creation of a top notch fighting machine.

Tough discipline and the boring life of drill, drill, drill resulted in not a few of the scarlet-coated soldiers seeking relief by escaping at the earliest opportunity. It was estimated that throughout the 19th century, five per cent of the British soldiers stationed in Canada deserted to the States annually. According to General Isaac Brock, those who fled were corrupted by vile characters from that country, who encouraged them seek a better life south of the border. To Brock's intense distress, not even his fabled 49th could "avoid the contagion."

|

|

49th Regiment Field Officer |

One plan devised to desert by several members of the 49th was foiled by Brock himself. The occasion occurred when Brock was stationed in York and Lieutenant-Colonel Roger Hale Sheaffe was in command of the garrison at Fort George. Driven to the brink by the brutality of Sheaffe, several soldiers decided to murder Sheaffe and then flee to the United States. Their plot was nipped in the bud by Brock, who immediately assumed command at Fort George and returned good order and discipline to the ranks of the 49th Regiment.

When Sir George Prevost, Commander-in-Chief in Canada, learned of the American declaration of war in June, 1812, he suspended British government orders to ship the 49th back to England. Instead companies of the regiment were dispersed to Montreal and Kingston. A number were also sent to Fort George where regimental headquarters for Upper Canada was located. On the eve of the outbreak of war, Brock said of the 49th "although the regiment has been ten years in this country drinking rum without bounds, it is still respectable and apparently ardent for an opportunity to acquire distinction."

It was not take long in coming for the Americans began their attack on October 13, 1812. In the first assault wave there were some 300 men of the 13th Infantry and an equal number of New York militiamen. Some quickly made their way up the winding footpath the the heights overlooking Queenston. A detachment of the 49th held a redan there, but the Americans made a surprise appearance and charging with bayonets drove them out. Brock was among the men and barely escaped capture.

Regrouping soldiers of the 49th led by Brock charged up the slippery slope to retake the battery and there on the approach to the heights the great general was felled by a bullet to the breast. Later that day raging "Revenge the General" the Grenadier Company and the Light Company of the 49th along with their Native allies soundly defeated the American invaders, many of whom died that day because of the fury felt by the 49th at the terrible loss of their leader. For their valor at this victory on Queenston Heights, Queenstown was added to the twenty-one battle honours emblazoned on the colours of the 49th. This honour was bestowed on January 27th, 1816.

The presence of another detachment of the 49th was sufficient to repulse a second invading American force led this time by the eloquent but ineffective American General Alexander Smyth. Smyth. Smyth was a better writer than a fighter and spent most of his time composing ringing declarations. "Ye who have the will to do, the heart to dare! The moment you have wished for has arrived. Think on your country's honours torn! Her rights trampled on! Her sons enslaved! Her infants perishing by the hatchet! Be strong! Be brave! Let the ruffian power of the British king cease on this continent."

In the early hours of November 28th, 1812, Smyth and an advance guard of American regulars and militia climbed into their boats and started across the river. Their objective was to destroy batteries opposite Black Rock and a bridge on the road to Chippawa. The expected fight was a fiasco when all suddenly returned to the safety of the other side.

An American assault on Fort George in May 1813 was successful. After spiking its cannons and destroying the ammunition, five companies of the 49th Regiment under the command of Brigadier-General John Vincent retreated westward up the peninsula with the enemy in hot pursuit. On June 5th as darkness descended the Americans gave up the chase and settled down for the night at a camp in a field at Stoney Creek.

|

After scouting the American position the second in command Major-General John Harvey recommended to Vincent that they launch a night attack on the enemy who were located some seven miles distant. At 2:00 a.m. with a force of 700 regulars, Harvey succeeded in catching the Americans off guard and fell upon them. The American pickets were bayoneted before they could give the alarm.

|

|

Battle of Stoney Creek by Jeffreys |

Chaotic fighting followed in the darkness and in less than three-quarters of an hour despite suffering heavy casualties, Harvey succeeded in capturing two American generals and forcing their troops to beat a hasty retreat leaving their cannons behind. Harvey had taken a calculated risk and succeeded. If he had failed the whole of the Niagara district might have fallen to the Americans. His success buoyed the spirits of British forces throughout Upper Canada and established him as an officer of unusual "zeal, intelligence and gallantry." Vincent missed the melee because he had been thrown off his horse, got lost in the darkness and only found his way to the British lines after the Battle of Stoney Creek was over. Harvey kindly and considerately omitted this from his report on the battle.

From its foes the 49th won the nickname Green Tigers because of the fierceness of their fighting and the colour of their facings. On one occasion a detachment of the 49th under the command of Lieutenant James Fitzgibbons was alerted by Laura Secord that an American force of 600 men was planning a surprise attack on them.

|

|

Laura Secord Warns Fitzgibbon |

Known as Fitzgibbon's Green Uns [because of their green facing] the detachment and several hundred Aboriginal warriors turned the tables on the Americans and ambushed them on June 24, 1813. On entering a beech wood, the Americans were set upon by the Native warriors. By firing at the enemy from widely dispersed positions, the warriors were able to trick the Amerians into thinking they were surrounded by vastly superior forces. After the battle had raged for some three hours, Fitzgibbon rode up to the Americans hoisting a white handkerchief and bluffed them into believing they were greatly outnumbered and that more warriors were expected at any time. The American surrendered. By stealth and by craft a victory had been achieved with a small force of fighters. Fitzgibbon was commended for his "most judicious and spirited exploit with '49 rank and file'." which resulted in victory at Battle of Beaver Dams.

|

|

|

49th Foot |

In His Own Words

"Not a shot was fired on our side by any but the Indians. They beat the Americans into a state of terror, and the only share I claim is taking advantage of a favourable moment to offer them protection from the tomahawk and the scalping knife."

Only once did the red-coated regulars have an opportunity in Canada to exhibit the training, courage and orchestrated killing that was displayed by British soldiers in set-piece battles in Europe. Major-General John Harvey also led this successful defence of our colony. The battle took place near the head of the Long Sault rapids on the St. Lawrence in eastern Ontario.

In a rough clearing in the forest criss-crossed by gullies, ditches and fences, the Battle of Crysler's Farm took place on November 11, 1813. The British force numbered 800 men; the Americans numbered 1800 which increased to 2400 during the fight. The Americans, mistaking the 49th regulars who were wearing their grey overcoasts for militiamen, charged with fanatical fervor. Although mired in mud the drill and discipline of the men of the thin red line proved its worth. Using manoeuvres of the line and shattering fire the 49th routed the regulars of the force three times larger who scattered into the surrounding wood. A charge by American dragoons was likewise deflected by infantry that never flinched in the face of thundering hooves. For heroic leadership at this decisive battle, small gold medals were awarded several officers.

Later companies of the 49th were ordered to Montreal, St. John and Isle aux Noix where they remained for the balance of 1813 and all of 1814. After an expedition to Plattsburg, New York the regiment assembled at Trois Rivieres and embarked for Great Britain on the 25th of May, 1815. Following distinguished service in Asia, Europe, Africa and Asia the regiment returned to Halifax in 1895. Two years later it sailed for Barbados then home to England in 1898. Reorganization resulted in the regiment being renamed the Royal Berkshire Regiment, the title 'Royal' bestowed in recognition of its distinguished gallantry.

The summer uniform of a private in the 49th Regiment private had half-length gaiters. His hair was tied in a pigtail which was tucked up under the hat. The knapsack was painted canvas. Haversacks were of grayish linen and worn on the left hip with a tin canteen. The large flap on the black cartridge box was to protect the pouch when open in wet weather. The hooked-back coat skirts were fastened together with little brass hearts that were found in great numbers in excavations. The 'necessaries' for a soldier included: two white stocks, one black horsehair stock, brass clasps or buckles for these, three pairs of white yarn stockings, two pairs linen socks, cleaning materials, combs, brushes, rations, water, blanket, ammunition, musket and bayonet. The musket was the Brown Bess, a .75-calibre, smooth-bore weapon weighing about ten pounds without the socket bayonet. In the hands of a well-trained man it could deliver one shot every fifteen seconds or so and men of the 49th were experts. They were so well-trained that regimental detachments of the 49th fought at the front of every engagement where their appearance inspired fear in the ranks of the foe.

|

|

Niagara Peninsula Battleground |

Copyright © 2013 Website Administrator