foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

41ST REGIMENT OF FOOT

History is shot through with passion.

|

|

Flag of the British Army |

|

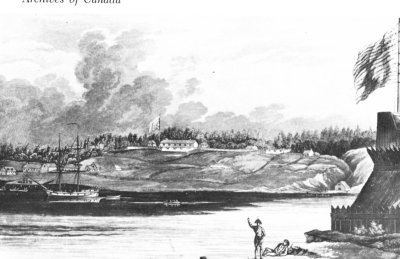

When word reached officers of the 41st Regiment garrisoned at Fort George that the United States had declared war on Great Britain they were hosting a dinner for their American counterparts from Fort Niagara, located a bugle call across the Niagara River where its waters merged with those of Lake Ontario.

|

|

Fort George, a bugle call away from Fort Niagara (right) |

After President Madison's declaration of war had been read to the assembled officers, their host, Major-General Isaac Brock, insisted they complete their meal and the dinner continued to a cordial conclusion. Then with military camaraderie and respect for civilized etiquette, the scarlet-coated officers strolled down to the river bank where they shook hands and bade their guests goodbye. The next time these military men met it would be at opposite ends of the cannon to commence the killing "of kindred people."

|

|

41st Foot |

"The 41st," said one authority, "was a stout battalion of old soldiers, but unfortunate in its colonel." That was rectified in 1800 when Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Procter assumed command of the 41st Regiment. Earlier the regiment had been described by Major-General Isaac Brock as being "wretchedly officered." The new commander turned the regiment around and Brock attributed its excellent condition to Procter's "indefatigable industry."

A detachment of the 41st Regiment which was known earlier as the Royal Invalids because it contained old veterans, was assigned to Fort George in 1806. One authority may have had this unit in mind when he wrote that the 41st "was a stout battalion of old soldiers but unfortuante in its colonel." More troops of the 41st Regiment under Procter were stationed at Amherstburg across from Detroit from where it was expected the first American assault would be launched. At the time the 41st was the only regiment of line in Upper Canada and but for its presence in the province, we might today be part of the United States. This highly trained, efficient force whose Welsh motto was Gwell angaa na Chwilydd - Death rather than Dishonour - wore a green feather on the helmet called a Shako. |

The men of the 41st Regiment, which saw savage fighting during the War of 1812, came to serve their sovereign from varied backgrounds. Statistics show the following representative groups of labour skills of men in this regiment which was raised in Great Britain and Ireland.

Former Occupation - Number

Labourers 145

Bakers 1

Blacksmiths 1

Brass Founders 3

Bricklayers 2

Butchers 6

Carpenters 1

Carriers -

Clerks 1

Coopers 2

Gunsmiths 1

Hairdressers 2

Hatters 1

Hosiers 4

Joiners 1

Masons 1

Millers 2

Miners 3

Nailers 5

Potters 2

Printers 1

The 41st distinguished itself on numerous occasions. In skirmishes near Detroit one incident, in particular, would have merited the Victoria Cross had it existed. Two privates named Hancock and Dean maintained their position while on sentinel duty "against the whole of the enemy's force" until both men finally fell. Hancock was killed. Though badly wounded Dean continued to oppose the advancing Americans with his bayonet until he was overwhelmed and captured. What motivated these men to such bravery? According to one military historian, displays of such bold bravery and great courage in the field were neither for flag nor national pride, but out of concern for one's comrades or determination to avenge their death.

In August 1812 Brigadier General William Hull invaded western Upper Canada, proclaiming to the people of Canada in a careful combination of promises and threats that he brought them "the invaluable blessings of Civil, Political and Religious Liberty." Brock promptly answered this bombastic public pronouncement with his own vigorous call to arms. He then wrote to his superior in Quebec, Sir George Prevost, "I propose collecting a force for the relief of Amherstburg." Members of the 41st Regiment comprised its main component.

On the 8th of August, 1812, Brock's tiny "mass of manoeuvre" consisting of 50 men of the 41st and several hundred militiamen embarked for Amherstburg. In an assortment of leaky boats they were buffeted about on Lake Erie by fierce winds and driving rain that nearly halted their progress, but they finally arrived at their destination in the early morning hours of the 13th. Shortly thereafter despite the hour, Brock convened a meeting of his officers at which he met Tecumseh for the first time. He was very impressed with the "sagacious and most gallant" Shawnee chief. The admiration was mutual for when Brock decided to take the offensive immediately despite the opposition of his officers, Tecumseh commented, "This is a man."

|

On the night of the 15th some 600 Aboriginal warriors led by Tecumseh crossed the Detroit River. Brock oversaw the siting the artillery. The cannons coughing flames and smoke began battering the fort across the river. A nine- or twelve-pound cannonball - so called because of the weight of the shot - fired at high velocity was a terrifying thing. The momentum created by its speed and weight made it capable of ploughing through massed ranks of men tightly packed together as they were according to the tactics of the day. Hull was well aware of the havoc cannon fire could cause. With a soft, menacing hiss "the grete gonnes" cannonballs moved lazily through the air towards their target and struck with tremendous force, ripping the ground open like a plough and shearing in their path through limbs and bodies.

A cannonball bounces each time roughly half the distance of its last bounce and if fired at sun-baked ground can bounce as many as five times leaving death and utter carnage in its wake. When fired into earth softened by rain it might simply plough into the mud and bury itself.

On the 16th Brock, a conspicuous target in his bright red uniform and gold braid, followed Tecumseh acoss the river with what Brock later described as "a gallant band" of regulars, militiamen and Native warriors. With this tiny force he launched his assault on Fort Detroit. As cannon balls rained down around the Americans, all Hull could hear was the blood-curdling shrieks of the Aboriginal warriors. He was panic-stricken at the thought of their actions on entering, especially for the lives of the civilians under his protection among whom were his daughter and grandchildren. Brock knew of Hull's fear of his ferocious allies and he had added to Hull's angst by indicating in his message to him that unless he capitulated, Brock might not be able restrain the Native warriors once fighting started.

|

|

Brock & Tecumseh |

Fearful of the fate of the civilians in his charge including his own family, Hull, as was his habit, nervously stuffed quid after quid of chewing tobacco into his mouth and anxiously pondered his position. When he received word that the American militia were deserting, he decided to fold without a fight and summoned his son to signal surrender. When Brock saw the white flag fluttering from the fort he was unable to believe his astounded eyes.

|

Later in his report to Sir George Prevost, Brock wrote, "When I detail my good fortune your Excellency will be astonished." So was everyone else in Upper Canada. Frenzied delight mixed with amazed disbelief swept through the province. No one could believe the news of this unexpected mastery over a military force to which many felt the province must surely succumb. One member of Congress had boasted that the American army's advance into Canada "could be resisted with as much success as the Falls of Niagara." Such Yankee pomposity and propaganda fostered this defeatism. When the contrary occurred with Brock's easy victory over these invincible invaders, every soldier, civilian and militiaman's morale soared and convinced many skeptics to commit themselves to the Canadian cause.

On August 25th a Victory Parade made its way down Queenston Road in celebration of Brock's conquest. The half-mile long spectacle of American prisoners of war, Aboriginal braves, militiamen and the Forty-First's red-coated regulars sweeping along with bayonets and buttons gleaming in the morning sunlight was a sight to behold.

|

On the other side of the Niagara River dejected Americans looked on this spectacle in sullen silence as Hull and his surly soldiers trudged to ships waiting on the Niagara River at Fort George to transport them to prison camps at York, Kingston and Montreal. An angry American officer who looked on recorded his feelings for a friend on the 28th of August.

In His Own Words

"Yesterday I beheld such a sight as I never expected to see. I saw my countrymen, free born Americans, robbed of the inheritance which their fathers bequeathed them, stripped of the arms which achieved our independence and marched into a strange land by hundreds like black cattle for market. Before and behind, on the right and on the left, their proud victors gleamed in arms, their heads erect in the pride of victory. The sensations the scene produced in our camp were inexpressible, mortification, indignation, apprehension, suspicion, jealousy, rage, madness."

Britain was delighted at the news and The Times of London printed a parody on the song Yankee Doodle.

Brother Ephraim sold his cow

And bought him a commission;

And now he's gone to Canada

To fight for his nation.

Brother Ephraim he's come back

Proved an errant coward,

Afraid to fight the enemy

Afeared he'd be devoured.

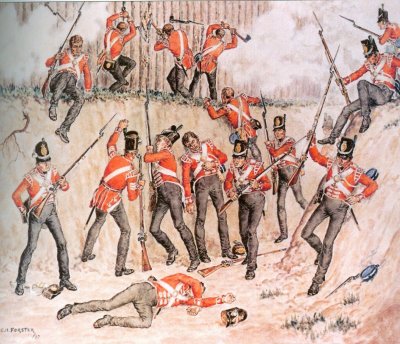

It was Tecumseh who suggested the next military move - an attack on the tough but tempting Fort Meigs on the Maumee. Procter knew Harrison was amassing troops at Fort Meigs and he decided to act before the enemy did and thereby keep faith with Tecumseh and his warriors. The attack failed and Procter prepared to return to Fort Malden. Tecumseh pressed for another assault this time on an American post named Fort Stephenson on the Sandusky River near where it emptied into Lake Erie. Procter agreed again. This too resulted in failure for the men of the 41st without scaling ladders could not hack their way into the well-fortified fort's log stockade and deep ditch. Despite repeated brave attempts to hack their way into the fort, they suffered severe fuscilades from the muskets of the Americans. Procter realized the fight was a failure and after more than a hundred men had fallen, he withdrew his shattered soldiers to Fort Malden.

|

|

Men of the 41st falling at Fort Stephenson |

Following Brock's death on October 13th, reinforcements for the 41st Regiment arrived at Queenston from Fort George and Chippewa. Commanded by Major-General Sheaffe they participated successfully in the Battle of Queenston Heights. Forces of the 41st led by Colonel Henry Procter also badly mauled William Henry Harrison's American sharpshooters at Frenchtown south of Detroit in January, 1813. This victory forestalled further American invasion attempts in the winter 1813 and earned a heartfelt vote of thanks from Upper Canada's Assembly. Similar success was achieved by the 41st at the Miami River on April 23, 1813. On another occasion by their spirited action the men of the 41st saved a number of British gunboats from capture by Americans in the Thousand Islands not far from Kingston. Plunging into the water and carrying their muskets over their heads, they waded through a creek and its swampy mud until they reached the other side where "they charged the enemy in gallant style."

However, dark days lay ahead for the 41st. In the fall of 1813 Harrison and his Kentucky cavalry entered Upper Canada at Amherstburg in pursuit of General Procter whose battered forces fled westward up the southwestern peninsula. On October 5th the Battle of Moraviantown took place. The 41st of Foot, Procter's own regiment, was by this time exhausted and in dire straits. Cold, hungry and weakened from fever and fighting, the regiment was routed by Harrison's riflemen who charged on horseback through its single line then dismounted to shoot at the backs of the British. Caught between a murderous barrage the demoralized men surrendered.

|

|

Battle of Moraviantown |

Accompanied by controversy and a few of his staff, Procter fled to safety at Ancaster. He was subsequently severely criticized for his lack of leadership and called to account at a court-martial in Montreal in December, 1814. Procter defended himself by blaming his troops, charging that the regiment's "former gallantry and steady discipline were badly tarnished." He said their conduct called for "reproach and censure."

It was not uncommon for a commander to blame his troops because their voices were always silent. No one spoke for the men. Nevertheless, Procter was found guilty of failing to prepare for his retreat, making faulty tactical arrangements and erring in judgement and execution. His punishment was only a reprimand but his career as an officer was effectively finished.

The 41st Regiment served with distinction for the remainder of the war and after the termination of hostilities the regiment withdrew to Quebec from where it returned to England in 1815. In 1831 the 41st received permission to style itself The Welsh Regiment. The Colours of the 41st contained 16 battle honours among which were Detroit, Miami, Queenstown, and Niagara, all battles that bore eloquent witness to the regiment's renown.

Copyright © 2013 Website Administrator