foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

THE LEGISLATURE AND EARLY LEGISLATION IN UPPER CANADA

History is what human beings did, thought, suffered and enjoyed and gives us the benefit of hard-won experience from the past.

|

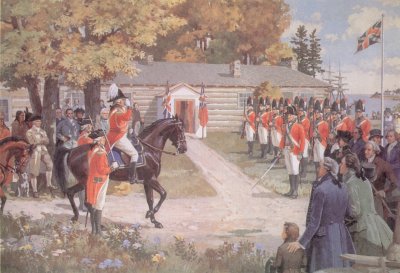

| Simcoe Opening the First Parliament of Upper Canada |

John Graves Simcoe was to preside over five sessions of Upper Canada's first Parliament. All were held at Newark [now Niagara-on-the-lake] in what Simcoe described as "sheds." These were additions made to Butler's Barracks by the Queen's Rangers "for the meeting of the Legislature and public offices."

Although the location of Upper Canada's legislature was plain and very primitive, the parliamentary practices used in the colony's first parliament were really quite sophisticated. They combined the rules of order used in the British House of Commons with those used in the American Congress. British parliamentary procedures were not new to some members of the Legislature for they or their parents had used them in the legislatures of the former American colonies. Loyalists like Hazelton Spencer's father, for example, had served as Speaker of the Virginia House of Burgesses for 27 years. Members of Upper Canada's House of Assembly were familiarized with British procedures by Governor Simcoe who had been a member of the British House of Commons before his appointment as lieutenant governor. Assemblymen also made use of a locally prepared ready-reference booklet titled Manual of Parliamentary Practice. This Ontario manual, an exact copy of the one written by Thomas Jefferson for use in the American Congress, omitted to mention Jefferson's name and had been thoroughly cleansed of any reference to American legislative procedures or American law and history.

|

|

Jefferson & His Manual |

Upper Canada's parliament met once a year and between the years 1792 and 1820, the sessions lasted on the average 31 sittings or days. The duration of each Parliament was five years unless it was prorogued or dissolved sooner by the Governor. All questions that came before the Assembly were decided by a majority vote of the Members present. In case of a tie the Speaker had a casting or deciding vote. On the opening day of Parliament the House met at noon but regular sittings usually began at 10 a.m. Unlike the British House of Commons, which sat five days a week, Upper Canada's House of Assembly sat Monday through Saturday. Each sitting commenced with a prayer which often became a sermon as the minister thought about the Members and warmed to his work.

|

The prayer was followed by the reading of the Minutes which were kept in Journals. In accordance with a 1792 rule, "every bill was to be read three times before it be sent to the Honourable the Legislative Council."

The question of a quorum, that is, the number of members required to be present so that the House of Assembly could carry on its legislative business, was left to be decided by the local legislature. Over the years this number was regularly revised because of the difficulty of getting members to attend on a consistent basis. On September 18, 1792, a resolution was passed which specified that nine members should "make a House," that is, comprise a quorum, but by October 10th of the same year this number had to be reduced to eight. In 1802 it rose to eleven and to 13 in 1812. During the last year of the war in 1814, it had to be reduced to eleven "due to some members being prisoners and others having disgracefully joined the enemy." On each opening day over the years the House frequently lacked a quorum.

Poor attendance of the members became a problem. In order to enforce regular attendance absentee members were fined and those owing fines were placed in the custody of the Sergeant at Arms and not released until the fines had been paid. Doctors of Members giving illness as an excuse for being absent were asked to appear at the bar of the House to testify as to their patients' actual state of health. Members planning on being away had to ask the House for a leave of absence.

|

Although the Speaker was supposed to represent and speak only for the House and its Members, he was not entirely free of government interference and pressure. Often in addition to holding the office of Speaker he held, thanks to government patronage, such positions as justice of the peace, sheriff, surveyor-general and judge. One Speaker was even a member of the Executive Council. This meant that when he expressed an opinion or made a decision he might not always have been representing just the interests or the point of view of the Assembly as should have been the case. In England the Speaker's ruling was the final word. Speakers in Upper Canada did not dominate the House and were not taken as seriously. Occasionally when the Canadian Speaker made a ruling it was appealed by the Members and on occasion overturned. Although respected the Canadian Speaker had neither the prestige nor the influence of the British Speaker of the House of Commons. One Member joked that perhaps this was due to the practice of Upper Canada's Speaker wearing a cocked hat rather than a wig as did the British Speaker.

|

The House of Assembly made extensive use of committees of the Members to draw up bills, consider petitions and investigate and report on matters such as: the state of the militia; the state of pensions; navigation on the St. Lawrence River and court fees. The Assembly's most important committee was the Committee on Public Accounts, whose five Members made detailed reports on the revenues of the province. Special Committees of the Legislative Assembly were also formed to meet and discuss issues with members of the Legislative Council.

The American Revolution convinced the British officials who created the Constitutional Act that democracy had caused the revolution because the people and their elected representatives could not be controlled. This grievous mistake would not be repeated in the Canadian constitution. The opinions of the appointed members of the

|

Legislative Council were given "a greater weight and consequence" than those of the elected Members of the Assembly. This made the Legislative Council the dominant branch of government. The Legislative Council's importance was reflected in the fact that 12 of its 20 members also served on the Executive Council. This was a kind of cabinet that advised the Governor and worked closely with him to run the colony. Only one member of the Assembly sat on the Executive Council. While the elected Assembly was the junior partner it was more than just "a debating society and a place for airing grievances." Before legislation could become law it had to be approved by the House of Assembly as well as by the Legislative Council.

Because political parties did not exist at that time there was no party discipline requiring each individual to carry out the party's policies. Consequently individual members of the House of Assembly exercised a fair degree of independence. Simcoe referred to this in a report he sent to Prime Minister William Pitt in 1794.

In Simcoe's Own Words"The members of the Assembly were motivated solely by the worth of the measure placed before them and by the confidence they had in the individual or individuals who proposed the legislation in the first place." They were not prepared to approve a piece of legislation simply because someone in authority told them to do so. Despite the Assembly's independent attitude Simcoe rarely had difficulty getting its members to approve his legislation. On those few occasions when they threatened to oppose proposed government legislation or to amend it, Simcoe usually managed to persuade them to go along with his proposals or to water down any changes they wished to make. On those few occasions when Members persisted in opposing government legislation, Simcoe angrily attributed it to republicanism or to "a spirit of vanity and sordidness."

In Britain only the House of Commons could originate money bills which meant that only it could introduce legislation to raise taxes. This right was not automatically passed on to its Upper Canadian counterpart, the Legislative Assembly. On the contrary in Upper Canada money bills were introduced by the Legislative Council. This practice was not challenged by the Assembly until 1816 when the Assembly began to protest that this privilege was their right and not the Council's. By challenging the Legislative Council over the right to initiate money bills, the House of Assembly made this very important legislative principle a part of the political process of Upper Canada. Over the years the bouts between the Assembly and the Council to assume its right to exercise various parliamentary procedures served to contribute to the reform tradition in the colony. The Assembly's fight with the Council for control over the right to levy and collect taxes foretold of the conflicts to come in 1837.

|

|

The Winner Taxes All |

Because their members were not united by loyalty to any one political party, they were not subject to party discipline. Consequently, relations between the Legislative Council and the Legislative Assembly were not always predictable. This meant that compromises had to be worked out through conferences between members of the Council and members of the Assembly. Between 1792 and 1820 over 60 such conferences were held.

|

Business in the House of Assembly was transacted quickly and Members' speeches were generally short. Unlike the situation in England's parliament domestic matters not foreign affairs occupied most of the Members' time. The very first act of the first session of the first Parliament dealt with the introduction of English law "as the Rule of Decision in all matters of controversy relative to property and civil rights." This was followed by "An Act to establish Trial by Jury." Legislation was approved setting various weights and measures, establishing small claims courts and fixing the amount to be charged in flour mills at not more than one-twelfth of the quantity of grain to be ground.

|

|

Guy Carleton, Lord Dorchester |

In 1788 Lord Dorchester created by proclamation four districts in that part of Quebec west of the Ottawa River which in 1791 became Upper Canada. Either to please George III, who came from Hanover in Germany or because a large number of Germans were among the first Loyalists to flood into the country, Dorchester had given the four districts German names: (1) Luneburg (later Lunenburg) extended from the western border of Lower Canada to the Gananoque River; (2) Mecklenburg extended from the Gananoque River to the Trent River; (3) Nassau included the country from the Trent River to Long Point; and (4) Hesse comprised the remaining western regions of the province. The Upper Canada Act passed in Upper Canada's first parliamentary session changed these names to: Eastern, Midland, Home and Western respectively. The same Act also directed that jails and court houses for each of these districts were to be located respectively in centres named New Johnston (Cornwall); Kingston and Newark. In the Western District the court house was to be located "as near the present court-house as conveniently may be." In 1816 the judicial centre for the Home district was moved from Niagara (Newark) to York.

|

|

Toronto Court House & Jail |

In the pioneer society of Upper Canada legislation was new and practical in nature since it was needed to foster growth in the new province operating under a new constitution. The emphasis was on getting new things established not on changing the way things were already being done. The first session of the Legislature lasted for a month and two days. It was prorogued by His Excellency Governor Simcoe on the 15th of October, 1792 after he had thanked the Members for the legislation they passed. Then by horseback, birch bark canoe or plain shank's mare the legislators left Newark and disappeared into the dense, trackless forests that lined the margin of the lake reflecting their inverted images on its glassy surface. Travelling around its fringe or along narrow trails that snaked through the great trees towering above them, they hurried to their distant homesteads where work awaited to prepare for the long, lonely, frigid months of winter ahead.

|

Prior to the commencement of the second session of parliament, Simcoe issued a proclamation on May 14th, 1793 informing a shocked and saddened public that on Feb. 1st, 1793, >"Persons exercising Supreme Authority in France had DECLARED WAR against His Majesty George III." The announcement included word that the French king, Louis XVI, had been guillotined on January 21st. News of the regicide horrified the citizens of Upper Canada. Members of the legislature viewed the declaration of war with alarm for it hinted at the possibility of an assault being made on Canada, one more threat to their tiny colony's existence. Although the United States claimed neutrality in this latest war between Great Britain and France, Americans secretly and some not so secretly supported France. Thomas Jefferson, who at the time was the American Secretary of State commented to a friend,

In His Own Words"All the old spirit of 1776 is rekindling and American newspapers have published the most furious philippics against England."

|

|

King Louis XVI of France |

American crowds cheered wildly whenever a French frigate arrived in Philadelphia harbour escorting a captured British ship with the its colours reversed and the French flag flying above them. Jefferson said he hoped it would be possible "to repress the spirit of the American people within the limits of fair neutrality." At the very least, he snickered, the Americans had "to preserve a sneaky neutrality." President Washington was anxious to avoid conflict with any country and proclaimed his nation's neutrality and "recommended to the various American States that they ensure a peaceful behavior towards the European Powers at war under pain of being out of his protection if they became involved."

No one took much notice of this warning and support for France flourished in America. Because of this the people and the government of Upper Canada feared an invasion from the south. They fully expected the Americans would take advantage of Britain's fight with France and attack Canada to rid North America forever of the British influence. Simcoe warned citizenry "To keep a good lookout on our frontiers." Upper Canadians warily watched the border and wondered when war would come. In this state of suspended alarm the second session of the first Parliament met at Newark on Friday, May 31st, 1793. The session lasted until Tuesday, July 9th. Among the Legislative Councillors present were Osgoode, Russell, Grant, Cartwright, Baby, and Hamilton. As might be expected during this tense, troubled time legislators focussed on the province's state of military preparedness.

|

|

William Osgoode Peter Russell William Hamilton |

Simcoe called for a remodelling of the militia and the Legislature readily responded to his proposals. Legislation was approved which authorized the appointment of a 'Lieutenant' for each county, who was to have the authority once a year to call out, arm, array and train the militia. All male inhabitants from 16 to 50 years of age could be summoned to serve in an emergency. For religious reasons Quakers and Mennonites were excluded from serving

|

in the militia but paid for this exemption from duty with 20 shillings annually in peace time and 5 pounds annually in time of invasion or insurrection. Simcoe had another reason for appointing lieutenants for each county. He believed the best defence against any encroaching democratic republicanism from the south was a landed aristocracy. In England Lord Lieutenants were appointed to supervise the loyalty of the people and to settle empty land and since Simcoe was determined to make Upper Canada a miniature mirror image of English society, he promoted "the existence of an aristocracy." A favoured few at the "head of the counties" would be chosen because they were "respectable and loyal" and because they had abilities, discretion, property and public confidence.

|

Simcoe expected that Upper Canada's 'Lieutenants' like nobility in England would become the "object of honourable ambition" and provide the "legal aristocracy which the Experience of Ages has proved necessary." Simcoe's plan to create barons in the backwoods received no support whatsoever from his superiors in London. He was informed that such officials would serve only to siphon off power from the lieutenant governor and Simcoe's plan was quickly quashed. Because the idea was not supported by the Colonial Office it was not continued by the governors who succeeded Simcoe. The last lieutenant Simcoe appointed was Robert Hamilton who became Lieutenant of Lincoln County.

The second session of Ontario's first parliament revealled that Upper Canada's Legislature had a cash flow problem. It suffered the same problem of many governments, that is, spending more money than it took in. The fledgling government found itself faced with the perennial problem of politicians: finding enough money to run the government. According to Simcoe the Members were "rather too liberal" with the salaries they had approved for the various government officials. He remarked wryly that the members themselves were "not averse to Parliamentary wages."

|

After stating that it was the ancient usage of England for the members to receive wages for their attendance in Parliament, Members enacted a bill "that every member should be entitled to demand from the justices of peace of the district in which his riding was situated a sum not exceeding 10 shillings ($2) for each day the member had been in attendance on the House with these amounts to be paid out of taxes."

Money was needed to run the government. The question was what and whom should be taxed? Simcoe himself was uncertain as to the best source of government revenues. "I confess myself much at a loss for a proper subject of taxation." He called upon members of Legislature for suggestions and they quickly responded, but there were differences of opinion as to the most appropriate sources of supply. Members of the Assembly liked the sin-tax type of taxation which has served governments well across the centuries. They approved a bill which taxed all spirits and wines entering the province from Lower Canada. It was calculated that all government expenses could be covered quite nicely if a duty of six pence a gallon was placed on liquor and wine. This would raise a revenue of 1500 pounds.

Legislative Councillors were aghast and termed this tax a rank injustice on the merchants of Montreal who were responsible for three-quarters of all the alcohol that entered the province of Lower Canada. They feared that such a tax would provoke misunderstanding and possibly even reprisal by the legislature of Lower Canada. Legislators in that province might very well approve some hurtful measure that could harm the economy of Upper Canada. Councillors defeated the Assembly's bill - called the Rum Tax - on second reading. This action created the first known instance of governmental gridlock in the province which resulted in no government legislation being passed since neither side could agree on a compromise. Government business was at a standstill.

|

As an alternative to the tax on alcohol the Legislative Council proposed a tax on property. This was quickly vetoed by the Assembly which declared it would be an barrier to immigration. Assemblymen feared such a tax would dissuade new settlers from coming into the country and buying the land many of them wished to sell. Simcoe reminded the Members that an earlier land tax called a Quit Rent had not deterred new settlers from coming into the province and said he saw no reason why a new land tax would stop the flow of incoming settlers. His words fell on deaf ears for as he informed his superior in London, "All arguments proved useless to persons actuated by their fears."

This stalemate on a money matter reflected an early divergence of opinion between the two classes. Members of the House of Assembly were willing to tax the wine and whiskey of the Council whereas members of the Legislative Council preferred to tax the land of the members of the Assembly many of whom were farmers. The impasse was finally overcome by an arrangement reached between Upper Canada and Lower Canada which resulted in an agreement that one-eighth of all revenues [taxes] received from duties on wines and liquors coming into the country would be given to Upper Canada. Because of its larger population Lower Canada kept seven-eighths of the revenue from this tax. In addition the legislature of Upper Canada placed a licence fee on the operation of all stills in the colony and imposed a tax per gallon on all spirituous liquors produced for sale locally.

Because the tiny settlements were encircled by trackless timberlands wolves and bears were a constant threat and a great nuisance to the settlers. In order to reduce the risk to life and livestock the Legislature enacted an environmental bill to decrease the numbers of wolves and bears, by paying a bounty of 10 shillings on each bear and 20 shillings for each wolf killed.

|

During this session bilingualism was introduced into the province when it was directed that all acts be translated into French for "the benefit of French-speaking inhabitants in the Western District" and any other French settlers who might decide to move into the province.

|

The session also produced a bill to create the province's municipal system. It provided for the selection of town officials. Simcoe opposed the election of these officers because he believed Town Meetings were to be discouraged. Such public meetings were carryovers from the American colonies and in Simcoe's opinion they smacked too much of democracy. He proposed instead that town officials be appointed by the magistrates. Members of the Assembly disagreed arguing that that citizens would be more inclined to respect and follow the leadership of men they themselves had elected. They pressed their case firmly and Simcoe finally saw the sense of their argument. He gave in and agreed to the election of municipal officials. The bill authorized the election by inhabitant householders of clerks, assessors, tax collectors, poundkeepers, town and church wardens, high constables and highway overseers. Though their powers were few the municipal councils became training grounds for future politicians and they are credited with eventually fostering responsible government.

Other legislation enacted in the second session included the laying out and repairing of highways. Neglect of road work by the municipalities led to the formation of private companies which maintained the muddy roads using planks and gravel. In turn the contractors were allowed to charge tolls on these roads. There were no tolls on Yonge Street, a fact that was cited as proof of the fineness of the land in that area. This was true most of the time except during heavy rains when even that road became a quagmire with "no sure footing for man or beast." The original Yonge Street was a source of much satisfaction for the early settlers who were grateful that it existed at all. South of what today is Yorkville it was virtually impassable. Further north it was a stump-strewn

|

swath edging ever so slowly through the dense forest. Beneath its great green canopy the newly arrived residents competed with bears and other beasts for survival. Among their many settlement obligations colonists were expected to help construct and maintain that portion of the road which passed by their land.

By far the most controversial piece of legislation in this session concerned the validation of marriages. In the early days of the colony there was a shortage of clergymen as a result of which marriages were performed by whomever happened to be handy. Over the years this included military commanders, adjutants, surgeons, justices of the peace and lay readers of the scripture. According to law these marriages were illegal and this meant that throughout the province there were many couples whose marriages were legally invalid. This meant that the children of such marriages were unable to inherit their parents' property. Action by the Legislature was needed and needed quickly in order "to settle what is past" and establish matrimonial regulations for the future.

|

Simcoe was horrified when the Assembly - most of whose members much to Simcoe's chagrin were not adherents of the Church of England - proposed a Marriage Bill that not only legalized all previous unions, but contained a rider that gave the power to perform marriage cermonies to ministers of every religious denomination and sect. Simcoe called this heresy. He was convinced that the members were prepared to

In His Own Words"make matrimony a much less solemn or guarded contract than good policy will justify. The suggestion is the product of wicked heads and disloyal hearts." As far as he was concerned the clergy of only one church could perform the marriage ceremony: the Church of England.

The governor promptly rejected the bill. Members of the Legislature feared they would lose the provision giving retroactive approval to all prior marriages and since this was something they all wanted badly they reluctantly compromised and removed the offending rider. Simcoe informed his superior, Lord Dundas, that because of "a general hue and cry of persons of all conditions" throughout the colony for the Marriage Bill, he could no longer withhold his approval and the Act as amended was approved validating all previous marriage ceremonies.

Thereafter any justice of the peace was authorized to join the happy couple in holy matrimony, but only until such time as there were five parsons of the Church of England in any one district. When this occurred these parsons and only these parsons were empowered to perform marriage ceremonies. In 1798 clergy of the Lutheran Church the Church of Scotland and the Calvanist Church were given the same right. In 1830 the right was extended to the clergy of most other denominations provided they procured a proper certificate.

From the very beginning parliamentary privilege and immunity from arrest for legislators was zealously guarded. During the second session the Sheriff attempted to do his duty by taking into custody one Honourable Member who had a claim against him. The House of Assembly reacted to this with righteous wrath and the Members directed the House Speaker to inform the Sheriff, "that the Assembly entertained a strong sense of the impropriety of his conduct towards a Member of this House." The poor sheriff was obviously ignorant of the fact that Members of the House were secure from arrest while the House was sitting as well as for forty days before sittings began and forty days after they ended. The sheriff was warned by the Speaker

In His Own Words"that if the Members had even the slightest suspicion that his actions were based on contempt rather than on want of reflection he would have been brought before the bar of the House where he would be required to kneel while judgement and punishment were pronounced against him by the Speaker."

One suspects the sheriff did not make the same mistake again.

In the second session of Upper Canada's Parliament Simcoe successfully pressed for the passage of a noble piece of legislation and in the process brought honour to the province. The legislation marked the beginning of the end of slavery in Upper Canada.

The third session of the first Parliament began on June 2nd and lasted until July 7th, 1794. It dealt first with a jury bill which specified that "not less than 32 nor more than 48 people" in each district would be called at any one time to "serve on trials at any Assizes." The assizes were periodic sessions of the colony's superior courts. Those who were summoned to jury duty and failed to appear were fined 20 shillings ($4). Compensation for jurymen was one shilling a day which was paid not by the province but by the plaintiff or his attorney. Because there was a shortage of lawyers in the province who were familiar with English Civil Law, legislation was approved which authorized the Governor to grant licences to sixteen of His Majesty's "liege subjects" to act as attorneys and advocates. Another act bolstered the militia by authorizing the formation of a cavalry unit and a navy. Another law allowed householders at their annual town meetings to determine in what manner and at what times horned cattle, horses, sheep and swine would be allowed to run at large. This bill also permitted the impounding of offending animals.

The fourth session of the first Parliament met at Newark and lasted from July 6th to August 10th, 1795. The first order of business was to regulate the practice of medicine which was known then as "the practice of physic and surgery." At the time Upper Canada was created there was no regulation regarding who could practise medicine or physic as it was then called. Some of the practitioners were old army or navy surgeons but most were mere emperics, that is, individuals with no training whatsoever but who relied solely on experiences they picked up as they went along. The act forbade the sale of medicine, prescribing medication for the sick and the practice of physic or surgery unless one was licensed. A board was to be appointed to examine all who applied for a licence. Any who were approved were granted a licence on payment of a fee of eight dollars. A penalty of $40 was assessed against those who violated this law. This act was found to be unworkable and it was repealed in 1806. Public pressure resulted in a new act being passed in 1815 but little occurred under this act and it too was repealed in 1818. This left the field of physic wide open for any and all would-be doctors.

The next piece of legislation dealt with citizenship. It prohibited any person from any place not within His Majesty's Dominions at the time of the passing of the act and any person not being a bona fide subject of His Majesty for seven years before the passing of the act from voting for a member of the House of Assembly or from being a candidate for the Assembly. This provision was directed at newly arrived Americans. It seemed to many Upper Canadians that too many settlers from the American republic were entering the province for land not love of the monarchy. Some of these types preached and even practised disloyalty to the crown.

An act was also approved that gave the Crown the right to seize smuggled goods which at that time included such things as 1000 pounds of tobacco, 1600 pounds of pork, 120 gallons of gin, 60 pounds of tea, 75 gallons of rum, and 88 pounds of snuff. Another act established a registry office for each county and riding.

|

|

A Registry Office |

The fifth and final session of the first Parliament lasted from May 16th until June 20th, 1796. Legislation was approved to regulate coinage and rate its value as legal tender in the colony. This was very necessary, for at the time all of the following currencies were circulating and accepted for tender in Upper Canada: the Johannes of Portugal, the Moidore of Portugal, the Doubloon of Spain, the American Eagle and the American dollar as well as numerous other gold and silver coins. Counterfeiting was considered such a serious crime it was made a felony punishable on conviction by death. Uttering, that is, using illegal tender was punishable on the first offence by one year's imprisonment and one hour "in and upon the pillory"¨ in some public place. The pillory, a wooden frame with holes in which the head and hands were locked, was a time-honoured punishment in English law and in Upper Canada. A prisoner so punished was required to stand in public pillory between the hours of 10 a.m. and 2 p.m.

For the second offence of uttering the punishment was death as a felon "without benefit of clergy." 'Without benefit of clergy' originally was a privilege extended only to Clerks in Holy Orders who got into trouble with the law. It meant that instead of being prosecuted in civil law courts, a clerk in holy orders would be turned over to the Church Courts which in most cases meant the individual was treated more leniently or completely cleared. This privilege gradually became extended to anyone who could read. Many who could not read simply memorized a passage which they then 'read' when asked to do so. This practice became known as "neck-verse," because 'reading' the passage saved one's neck. The provision was abolished in Canada in 1833. Another act abolished the bounty on bears; the one on wolves remained in effect because they continued to be a problem.

Even at this early date there were differences of opinion in the Legislature. The Council Members generally were more inclined toward the aristocratic point of view while Members of the House of Assembly tended to display a more democratic attitude. The beginning of an opposition began to appear at this time in the persons of Robert Hamilton and Richard Cartwright, two wealthy and influential members of the Legislative Council. They never hesitated to disagree with the governor or the government. On one occasion they joined forces to oppose a government measure to form one central court to be called the King's Bench. This court was intended to replace various local courts spread throughout the colony. The two men felt that with a "thin population scattered over so great a country" and with travel being so difficult that a central court presented real hardships for those who had to use it. They argued that it made more sense to have courts across the colony for easier access.

Simcoe disliked opposition of any kind and was particularly incensed by these two men who never hesitated to speak out in opposition to proposals with which they had an honest disagreement. It was customary at the time to publicly discredit and ridicule anyone who had the temerity to oppose government policies or proposals by labelling them 'republicans,' a derogatory term meaning someone who supported the detested American system of government.

The first Parliament was the only one convened in Newark. Thereafter, parliament and its politicians moved across the lake to York which became the new capital of the young province. At the time York was a compact little rectangle bounded on the west by George Street, on the east by Ontario Street, on the north by Duchess Street and on the south by Palace, now Front Street.

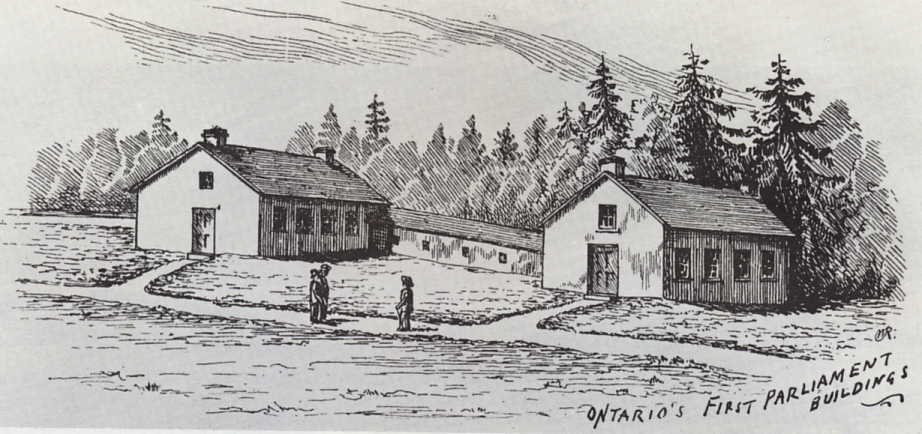

Palace Street was so named because it was to be the site of the Parliament buildings [See below], the only 'palace' York was to have for some time. The parliament buildings were constructed near the intersection of Front and Parliament Street, initially a bridle path hacked out of the woods.

On July 10th, 1794 an advertisement appeared in the Gazette, the official government newspaper."Wanted, Carpenters for the public buildings to be erected at York. Applications to be made to Mr. John McGill, Esq., at York or to Mr. Allan McNab at Navy Hall." The public buildings were to accommodate government officials and the Legislature. It was not long before signs of construction lay strewn about the site: "hewn logs, beams, some scantling and plank with bundles of cleft shingles drawn there over the snow from shanties in the adjoining woods, where with the help of broadaxe, adze, and whip-saw such objects were prepared. Heaps of lake shore stone or small surface boulders to aid the foundations and a few bricks for the chimneys made from a kiln."

The exact site of this structure was unknown until recently when the mystery surrounding the location of Canada's first Parliament buildings was finally resolved by archeologists who unearthed the remains of what they described as a historical treasure.

The Toronto Star, October, 2001.

|

|

Ontario's First Parliament Buildings |

Torontonians could figuratively peel off the pavement under the car wash, rental car agency, parking lot and empty buildings on the south side of Front St. E., between Parliament and Berkeley Sts., and peek underneath to see the "cradle of Ontario's democracy." Despite doubts by many who dismissed the possibility of unearthing the parliamentary complex that was first built in 1797 archeologists confirmed yesterday that the pickings from their dig at the site last fall were, in fact, relics of the historical architecture. In light of the conclusive identification of the remains the site is clearly of local, provincial and national significance archeologist Ronald Williamson told a news conference in Toronto yesterday. "It is difficult to imagine an archeological feature that is more deserving of a co-ordinated heritage conservation effort."

Among the evidence examined by a team of historians, material culture specialists, lithic (stone) analysts, a botanist and a zoologist are hundreds of pieces of plates and crockery, charred fragments of wooden floor joists and floorboards, lime-sand mortar and creamware ceramics traced back to the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Williamson said the charred wood and bricks are consistent with the burning of the Parliament Buildings by American forces in the War of 1812 and the footing consisted of Gull River formation limestone quarried at Kingston by the 1790s.

Together the bits and pieces at the dig which consisted of a 2-metre-deep trench cut out of asphalt, open a window into the first Parliament's two west-facing brick buildings that measured 13 by 7 metres and were set 24 metres apart by a covered colonnade. These buildings, where the House of Legislative Council and the House of Legislature Assembly sat, were destroyed in the spring of 1813 by American forces but quickly rebuilt to house British troops and later used as lodgings for new immigrants.

In 1820 a new seat of government was built on the same site with the original buildings reconstructed as wings and the space between filled with a centre block. But the second Parliament buildings only stood until 1834, when a kitchen fire burned down some of the structure. The buildings were largely derelict until March, 1830 when the remaining materials from the shell of the structure were sold by public auction. Between 1837 and 1840 the site was the Home District Gaol (Jail) which was demolished by the Consumers Gas Co. in 1887 for an office building. It sold the site in the 1960s and had it redeveloped as it is today.

First Parliament To Be Preserved

Dec. 21, 2005. 03:59 PM

FROM CANADIAN PRESS

The property in downtown Toronto at the corner of Sherbourne and King Streets is the site of Upper Canada's first Parliament. Underground artifacts are all that remain of the brick buildings built in the late 18th century. The buildings were burnt to the ground by invading U.S. troops during the War of 1812. Meilleur says the Ontario Heritage Trust will develop ways to ensure the long-term preservation of the site. "The site of Ontario's first parliament buildings is our cradle of democracy and a site of historical significance," said Meilleur. Lincoln Alexander, trust chairman and former lieutenant-governor, said the agency was delighted to assume the lead role in the preserving the site. "It is the birthplace of our systems of courts, land ownership and civil freedoms and democratic traditions that are the very measure of our strength as a province and as a society," said Alexander.

Site of Ontario's first parliament buildings back in public hands

Dec/ 22. 2005

National Post

A piece of land where Ontario's first parliament buildings once stood is again public property, after the provincial and city governments acquired a small plot yesterday at the foot of Parliament Street. The province and city obtained the property at 265 Front Street E., currently the site of a Porsche dealership, in a land swap that followed 2 1/2 years of negotiations. Archeologists found the site of Ontario's first parliament buildings in 2000, when they uncovered shards of pottery dating back to the late 18th centruy amid the charred remains of two brick structures during a dig at 25 Berkeley Street. It was determined that the building lay under three different properties: a gravel parking lot just south of 25 Berkeley St., a lot at 271 Front St. E. and another at 265 Front St. E. The Ontario Heritage Trust will take ownership of the plot and assume the role of lead heritage agency in developing the land. Plans for the place are still "a work in progress."

The two legislative buildings [*] were the first brick buildings in the settlement that would eventually become Toronto. Construction of the buildings was finished in 1797. They were destroyed in 1813 [**] when American soldiers looted and burned them down in a raid during the War of 1812.

[*] John McGill to Simcoe [***], Sept. 27 1797: "I trust it will afford your Excellency some degree of satisfaction to learn that the rafters are up on one wing of the Government House and that in about three weeks the brick work of the other wing will be completed. Having the winter before us I have no doubt but that both of them will be in such forwardness as to be fit for the next meeting of the Legislature, though the two attached houses answered exceedingly well for the last session." [*] President Peter Russel to Simcoe, Dec. 9, 1797: "The two wings to the Government House are raised with brick and completely covered in. The South one being in the greatest forwardness, I have directed to be fitted up for a temporary Court House for the King's Bench in the ensuing term, and I hope they may be both in a condition to receive the two houses of Parliament in June next. I have not given directions for proceeding with the remainder of your Excellency's plan for the Government House, being alarmed at the magnitude of the expence, which Captain Graham estimates at 10,000 poounds. I shall, however, order a large kiln of bricks to be prepared in the Spring and burnt (as they will readily sell for what they cost if Government does not want them) and Boards and scantling may be cut and seasoned upon the same principle. I sincerely hope to have the pleasure of seeing your Excellency here before we shall have occasion to proceed further with the building." The provincial parliament met at York for the first time in the two brick buildings constructed as public offices on June 8, 1798. The session continued until July 5. [****] were passed. In his closing address to the House at what he described as "this very critical and eventful period," The administrator, John Russell stressed "the necessity of enforcing your militia laws that your active vigilance in your respective stations may render it difficult for any person to screen himself from being enrolled in some militia Corps so that every man capable of bearing arms may be held in constant readiness to assist in repelling all hostile attempts against either province " McGill to Simcoe June 8, 1798: "Our Provincial Parliament meets this day in the two brick Government Buildings but owing to the insufficiency of members present the House is adjourned until tomorrow." [**]The occupation of York ended with American soldiers setting fire to the legislative and administrative buildings. [***] By this time Simcoe had returned to England and although McGill fully expected that he would return as Governor General of all British colonies in Canada, Simcoe never did. [****] Only seven acts were passed. Two of these were reserved for the royal consideration and the others were approved. Two acts originated in the Legislative Assembly with the intention of remedying obvious grievances.The first of these was intended to ensure more uniform assessments by depriving the elected assessors of being "the judges of the Quantity and value of every man's real and personal estate."

The second dealt with the performance of statute labour. This referred to work on public roads and was intended to ensure that the proportion of labour on roads carried out by each individual was regulated by the value of his ratable property.

Russel reserved these for the King's approval.

A third act introduced in the Legislative Council established permanent boundaries for existing townships. Death was to be the sentence for anyone tampering with boundary markers. Two acts, were sponsored by the Chief Justice.The fourth created four new districts by dividing the existing ones and they were named: Johnstown, Newcastle; Niagara; and London.

The fifth separated the northern parts of counties in the Eastern District, which were thinly populated, from the southern parts and formed three new counties: Prescott; Russel; Carleton. The six and seventh acts amended former acts that regulated the licensing and appointment of advocates, attorneys, solicitors and notaries and extended the jurisdiction and regulated the proceedings of district courts and courts of Requests.

Copyright © 2013 Website Administrator