foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

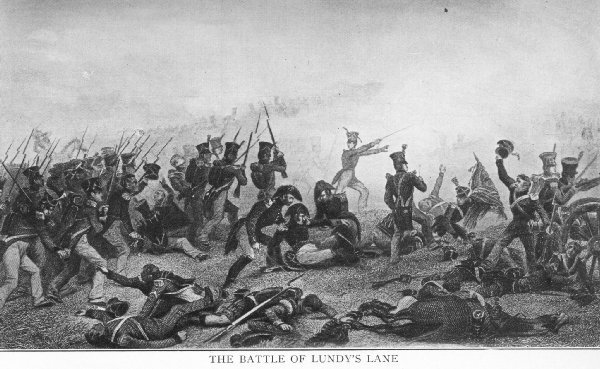

BATTLE OF LUNDY'S LANE

"History in some sense is always propaganda."

Today the sloping site of the bloodiest battle in the War of 1812 is a church grave yard and an elementary school appropriately named Battlefield Elementary School. Occupying the crest of the rise is Drummund Hill Presbyterian Church. Peace and quiet - except during recess - permeate the place made sacred by the blood of British and American soldiers intent on holding the heights that sultry summer evening one hundred and ninety two years ago. The battle like the war that neither side won is claimed as a victory by both combatants.

President James Madison, whose public career was a series of contradictions, compromises, doubts and fears, started it all by declaring war on Great Britain on June 18, 1812. In a subsequent proclamation to the nation Madison exhorted the good people of the United States to "exert themselves in supporting and invigorating all the measures which may be adopted by the constituted authorities for obtaining a speedy, a just and an honourable peace."

Over two years later on September 20, 1814 in his Sixth Annual Message to Congress, Madison voiced his rather embellished version of events on the Niagara Peninsula. "On our side we can appeal to a series of achievements which have given new lustre to the American arms. Besides brilliant incidents in the minor operations of the campaign, the splendid victories gained on the Canadian side of the Niagara by the American forces under Major-General Brown and Brigadiers Scott and Gaines have gained for these heroes and their emulating companions the most unfading laurels and having triumphantly tested the progressive discipline of the American soldiery have taught the enemy that the longer he protracts his hostile efforts, the more certain and decisive will be his final discomfiture."

Prelude to the Battle of Lundy's Lane

On May 25th, 1813 ships in the Niagara River commanded by Oliver Hazard Perry along with the newly constructed batteries at Fort Niagaara began bombarding Fort George. The flimsy fort was not the object of their cannonade which was directed at the garrison therein commanded by Brigadier General John Vincent. |

|

Fort George from Fort Niagara |

Two days later an American force numbering some 5000 led by Colonel Winfield Scott stormed ashore at Two Mile Creek. Vincent, who was only too conscious of the limitations of his own forces, ordered the guns spiked, the ammunition destroyed and the fort evacuated. The British retreated westward to Beaver Dams on the escarpment where Vincent summoned British forces stationed at Fort Erie, Queenston and Chippawa to join him. Later Vincent, who was promoted to major general on June 4th, withdrew to Burlington Bay, a strong position high above the lake with easy access to a harbour and land routes to both York and Amherstburg. The Americans now controlled the whole of the Niagara frontier.

|

|

British Major General [See Below * ] |

Following Vincent an American force bivouacked for the night at Stoney Creek where they were surprised and defeated in a night attack. This was a decisive victory for it stopped the American advance into the Niagara Peninsula. The remaining Americans set fire to Fort Erie, withdrew from it and Chippawa and retreated to the corner of the peninsula around Queenston and Fort George. A second attempt was made to penetrate Vincent's defenses when some 500 Americans under Colonel Boerstler left Queenston on June 23rd to capture the British post at De Cew's house commanded by Lieutenant James Fitzgibbon.

|

|

British Lieutenant |

Learning of Boerstler's plans, Laura Secord set out to inform Fitzgibbon about the enemy force advancing to attack the stone house in which he was quartered which she succeeded in doing at 7 o'clock on the 24th of June. Shortly thereafter Fitzgibbon on hearing cannon and musketry fire rode out to reconoitre. He found the enemy engaged in combat with some 300 warriors from Lower Canada and a hundred Mohawks led by Captains William Kerr and John Brant. They were harrassing the foe's flank and rear and "galling him severely." Enraged by the loss of their brethen the warriors fought savagely.Their horrific hooting and hollering terrified the Americans who were desperately fighting a fiercesome, phantom-like foe they could scarcely see. Hemmed in by a swamp on one side and the Natives on the other, Boerstler gratefully grabbed at Fitzgibbon's presence and surrendered to him and his 50 49ers. The victory belonged to the Aborignals and Fitzbibbon acknowledged this when he later recorded, "... not a shot was fired on our side by any but the Indians. They beat the American detachment into a state of terror." Despite Fitzgibbon's acknowledgement there were some who believed the British officer exaggerated his own involvement. John Norton uttered the classic statement, " The Cognauaga [* *]Indians fought the battle, the Mohawks got the plunder and Fitzgibbon got the praise."

This victory resulted in an impasse. The American forces were concentrated at Fort George unable to break out, while British and Canadian forces round about them were unable to break in. Both settled down and awaited the outcome of conflicts elsewhere. These required heavy reinforcements which reduced the regular American troops available along the Niagara frontier. By December British troops had retaken most of the frontier with the exception of Fort George occupied by Brigadier General George McClure and a few hundred state militiamen who were reaching the end of their term of service and pressing to return to their homes in New York. On hearing that British Colonel John Murray was advancing against the fort, McClure decided to abandon it. Before doing so he issued his infamous order to torch the houses roundabout in the dead of winter. "Nothing but heaps of coals and streets full of furniture the inhabitants were fortunate enough to get out of their houses met the eye in all directions." Four hundred men, women and children were rendered homeless in bitter winter weather. This was another barbarism in a barbarous war.

The British had quick revenge. Lieutenant General Gordon Drummond had arrived at Upper Canada in August of 1813 to assume responsibility for the administration of the province and to take command the British forces stationed there. He was accompanied by Major General Phineas Riall, the replacement for Vincent who had been given command of the garrison at Kingston. On arrival at Fort George on December 16, Drummond was greeted by a pathetic populous and demands for retribution. He heard and immediately ordered Murray to attack Fort Niagara which fell quickly and yielded a great quantity of ammunition and supplies including a thousand pairs of shoes.

Shortly thereafter Riall with a force of regulars and warriors crossed the river and encountering virtually no opposition, captured Lewiston whose guns threatened Queenston. After destroying Lewiston Riall proceeded to raid Youngstown and a Tuscarora village leaving both in charred ruins before returning to Fort George. Intent on ensuring the complete elimination of any threat to the Niagara frontier, Drummond ordered Riall to re-cross the Niagara River which he did at Chippawa on December 29th. He burned Buffalo and Black Rock in order in Drummond's words, "to deprive the enemy of the cover which these places afford." The raid was a total success and within the three-week period the situation had been reversed: the British had secured possession of the frontier. Lamented one American commander to the Governor of New York, "The flourishing village of Buffalo is laid in ruins and the Niagara frontier now lies open and naked to our enemies."

|

|

Burning of Buffalo |

Things were quiet until early June when Riall reported to Drummond at York that enemy action was evident and military movements indicated an offensive was not far off. It came in July 1812 and resulted in American forces capturing Fort Erie and establishing a foothold on the frontier. On July 3rd some 4000 men under Major General Jacob Brown set out for Burlington Heights. Preparing to confront and repel these raiders, Riall after ordering reinforcements to follow, left with a force of light companies for Chippewa, some eighteen miles north of Fort Erie.

|

|

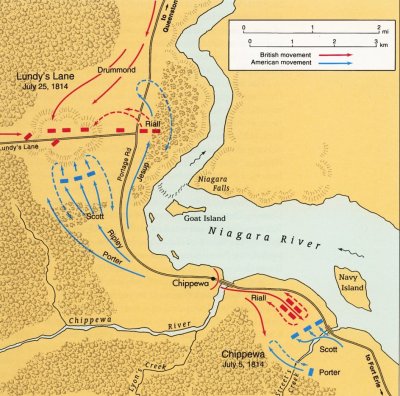

Map of the Battles of Chippewa & Lundy's Lane |

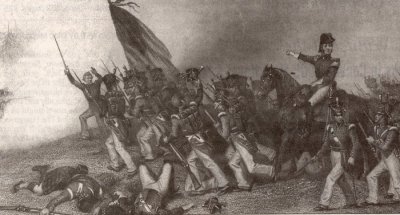

On arrival Riall prepared to pit his 1500 men against Brown and Winfield Scott's advance guard of 2000. He believed because the troops were dressed in grey uniforms that they were members of the American militia. Too late he realized he was mistaken. The steady discipline and the precision, parade-ground manoeuvring of Scott's men facing British fire led Riall to exclaim in surprise, "Those are regulars, by God!" The two forces met at Chippewa in a classic European-style battle. Riall leading bravely from the front was bested by the well-trained Americans. He broke off the attack and retired from the field, the humiliated general being one of the last to leave.

|

|

American Charge at the Battle of Chippewa |

British losses totalled more than 350 men killed or wounded or missing and presumed captured, while Scott's forces suffered 300 killed, wounded or missing. While not an important victory, the battle's psychological effects were significant. Regulars on both sides met and manoeuvred on an open plain and the Americans won. This battle is commemorated by the grey uniforms worn by cadets at the United States Military Academy at West Point.

|

|

Battle of Chippewa [U.S. National Archives] |

Following the American victory Riall retreated all the way back to Fort George with the Americans in hot pursuit. Brown's forces then encamped at Queenston where they awaited the arrival of Commodore Chauncey's naval force for a joint assault on the British occupying forts George and Niagara. However, Chauncey wanted no part in the offensive, declaring he had no intention of serving as "an agreeable appendage" to Brown's army and simply never showed up. After waiting two weeks for the navy to arrive, Brown decided it was beyond his military means to attack and fearing being routed the redcoats, he withdrew his soldiers to Chippawa. Riall followed with his forces. Meanwhile Drummond after dispatching another British brigade to menace the American depot at Fort Schlosser, followed Riall with additional troops.

The Battle of Lundy's Lane

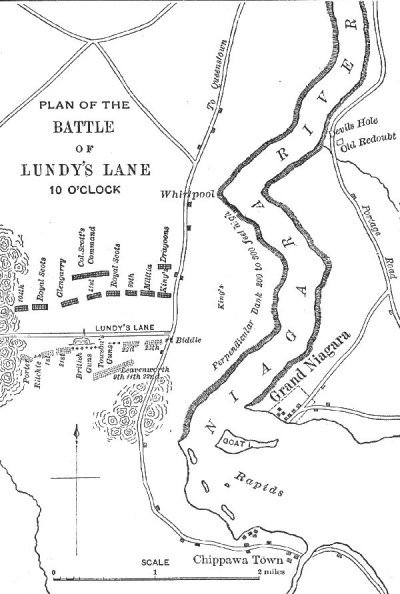

When Riall arrived at Lundy's Lane, a low hill no more than 25 feet in elevation about a mile from the falls, he positioned a battery of six cannons on the ridge and deployed his men in defensive positions. He had been ordered by Drummond to follow and harass the enemy but not to confront them in battle. When Brown learned about the British raid on Lewiston and that another British brigade was advancing on Fort Schlosser, he feared for his communications on the east bank of the river and decided to initiate an offensive of his own on the west bank to draw off some of the British forces on the east side of the river. He ordered Scott's brigade to advance from Chippawa. Before long Scott encountered Riall's forces at Lundy's Lane and on July 25th, 1814 prepared to move against their position. In accordance with Drummond's directions to avoid a confrontation with American forces, Riall ordered the withdrawal of his forces only to have that countermanded by Drummond who had just arrived with reinforcements. Intent on driving Brown out of the province, Drummond prepared for battle.

|

|

British Artilleryman |

The two armies clashed that evening around six o'clock. Within twenty paces line engaged line separated by a perfect sheet of fire. Both sides opened up an intensive artillery fire, the British 24-pounders of the Royal Artillery tearing up the American attackers. Early in the conflict Rial was wounded in the arm and as he was being borne away the shout went out, "Make way for General Riall!" The Americans quickly obliged for Riall's stretcher-bearers were confused by the twilight and headed right into the American lines. Riall spent the rest of the summer and fall in comfortable captivity. A fellow prisoner, a young militia officer named William Hamilton Merritt, described Riall as "very brave, near-sighted, rather short and stout." Riall was released on parole in November and before departing for England, the caring commander visited all other British prisoners.

T |

|

Plan of the Battle of Lundy's Lane |

|

|

|

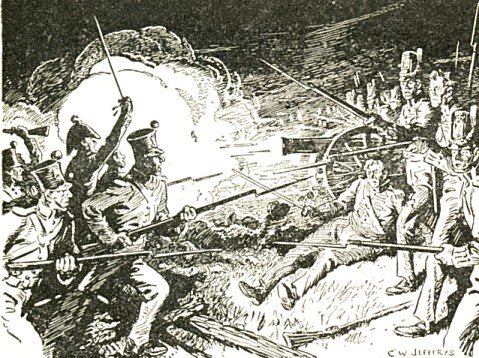

With the arrival of reinforcements, the American forces numbered some 3000 and British about 2800. Believing he was badly outnumbered Drummond threw caution to the winds and decided to take the defensive and hold off American attacks on his position. His foe failed to make any impression on the centre of the line despite repeated attempts. Charge after charge was beaten back by the British battery. Drummond wrote, "Of so determined a character were the attacks directed against our guns that our artillery men were bayonetted by the enemy in the act of loading and the muzzles of the enemy's guns were advanced to within a few yards of ours." About nine o'clock one regiment of Ripley's brigade succeeded in seizing the British guns on the crest and driving Drummond's forces back several hundred yards. For the next three hours Drummond counter-attacked unsuccessfully three times. British regulars pressed the American line taking severe punishment from cannon and musket while at the same time repelling American columns attempting to outflank their line. During one of these assaults Drummond while rallying his regulars in the darkness was wounded in the neck.

|

|

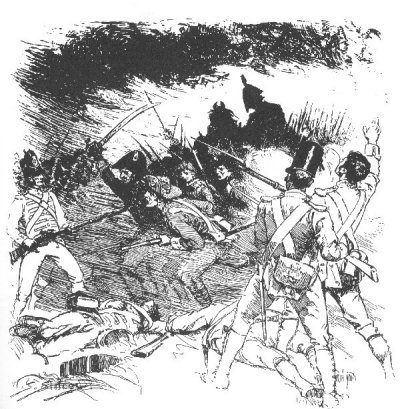

Charge! |

Desperate charges took place from dusk to darkness with the heroics of war evenly divided, volleys being exchanged almost muzzle to muzzle. The crack of muskets and the roar of cannon were almost continuous with great clouds of smoke arising that almost blotted out the light of the moon. "Both armies fought with a desperation that bordered on madness." The battle see-sawed back and forth until midnight when the American offensive thrust was spent and a party of light infantry recaptured the British guns. Scott, who had two horses shot out from under him, went down with a bullet-shattered shoulder. About the same time, Brown, who was crippled by wounds, ordered Brigadier General Eleazir Ripley commanding the dazed and bleeding American defenders to withdraw. Drummond was content to lick his wounds and an equally exhausted British army held the field unable to follow.

At daybreak both armies had their ranks diminished by a comparable number of casualties: Reported by the British: 84 killed; 559 wounded; 235 missing. Reported by Americans: 171 killed; 572 wounded; 117 missing. [* * *]. The battle was the hardest and bloodiest of the war fought in Canada. In the cold light of day it became obvious to Ripley that his forces were exhausted and would not be replenished. Drummond wrote, "The enemy abandoned his camp, threw the greater part of his baggage, camp equipages and provisions into the rapids and having set fire to Streets Mills and destroyed the bridge at Chippawa, continued his retreat in great disorder towards Fort Erie." Had Drummond followed closely on the heels of the retreating Americans and forced them to fight again victory might have been complete. The fiery fight that night was the sharpest of the war on Canadian territory. It was a tactical standoff but a strategic victory for Drummond. In the words of Winston Churchill, "The advance from Niagara was checked by a savage drawn battle at Lundy's Lane near the Falls.

|

|

The Cut and Thrust of Battle |

Various versions of the Battle of Lundy's Lane taken from the following sources.

Encyclopedia of American History

During the War of 1812 the British movement towards New York was met by Gen. Jacob Brown who took the initiative and met the British at Lundy's Lane near Niagara Falls in Canada. Brown out-fought the enemy but fell back when he learned that strong British reinforcements were on the way. Both sides claimed victory.

Messages and Papers of the Presidents

After his defeat at Chippewa in 1814 General Riall retired by way of Queenston toward the head of Lake Ontario. He was soon reinforced and returned to attack the Americans under Brown who had pursued him as far as Queenston. Hearing of British reinforcements Brown retreated to the Chippewa River and on July 24, 1814 encamped on the south bank where he had defeated Riall on the 5th. On the 25th Gen. Scott, with about 1,200 men, went forward to reconnoiter and came upon the British army, 4,500 strong, near Niagara Falls, on Lundy's Lane. a road leading from the Falls to the end of Lake Ontario. Soon the entire American force was engaged. the battle lasting from sunset until midnight. The American forces numbered about 2,500 men. During the engagement Gen. Scott and Lieutenant Colonel Miller distinguished themselves for daring and efficiency. The British were finally driven back and forced to abandon their artillery, ammunition, and baggage. Both armies claimed the victory though both left the field. The American loss was 171 killed, 571 wounded, and 110 missing - a total of 852 out of nn army of 2,500. The British lost 84 killed, '559 wounded, 103 missing and 42 prisoners - a total of 878 out of an army of 4.500. Generals Brown and Scott were among the wounded.

From Sea to Shining Sea

Brown followed up Scott's victory by pressing the British back to Fort George and Burlington Heights. Encamping at Queenston, he awaited the heavy guns needed to reduce the enemy forts. They were slow in coming from Chauncey at Sackets Harbor, and Brown was forced to return to Chippewa on July 24. In the interval, General Drummond had hurried to the Niagara from Kingston. He now ordered his three thousand-man force out in pursuit of the Americans. While Riall followed Brown, another force crossed the river to menace Brown's supplies. Brown became worried. He sent Winfield Scott down the Canadian side of the river in hopes of forcing the enemy to recall his troops from the American side. Scott came upon Riall at Lundy's Lane, a point a mile below the falls, and immediately attacked.

Such was Scott's audacity that Riall was forced to retire. But just then Drummond came up with the rest of his army, ordering the cross-river detachment to rejoin him. Drummond put his artillery on a hill, with his infantry in line slightly to the rear. Scott attacked again, directing his brigade against the British center and left. On the left, the Americans temporarily turned the British flank, capturing the wounded Riall while doing so. But the British eventually recovered there, while in the center they hurled back charge after charge. Still Scott hung on, until, at about five o'clock, Brown arrived with the rest of his army.

Brown ordered another attack. The lines swept forward in a darkness shimmering with the flashes of the British guns, but they could not seize the hill and the British battery blazed on. Brown ordered Colonel James Miller of the 21st Infantry to take the British works. While the enemy guns thundered at an American column moving along the river. Miller's regulars slipped forward through the darkened scrub. Coming to within a dozen yards of the enemy, they crashed out a close volley, charged with the bayonet and seized both hill and battery. Now Brown brought his entire army up to the hill, and the astonished Drummond counterattacked. Three times the dark silhouettes of the British regulars swept upward, and three times the muzzles of American muskets and the captured guns flickered and flamed to drive them back again. Brown and Scott were both hit and evacuated. Around midnight, Brown ordered Ripley, now commanding on the hill, to withdraw for water and ammunition. He did, but he also left some of the enemy guns behind. With daylight Drummond quickly reoccupied the height and turned the guns around-restoring the situation of the preceding day except that both sides were battered and bleeding and each minus about nine hundred men.

In the Battle of Lundy's Lane the Americans might just possibly have won a tactical victory, but they suffered strategic defeat. Lundy's Lane put out the ardent flame enkindled by Chippewa and forced Brown to abandon all hope of conquering Upper Canada. He withdrew into Fort Erie. The energetic Drummond assaulted him there on August 15, but the American repulsed him. On September 17 Brown led a sally out of the fort to seize and spike the British guns. No less than five hundred men fell on both sides during this bitter flare-up, and now both Brown's and Drummond's armies were exhausted remnants. Drummond issued orders proclaiming a victory, and then fell back to Chippewa. Less than two months later the Americans acknowledged the futility of fighting on the Niagara Frontier by blowing up Fort Erie and recrossing the river to American soil.

All had not been in vain, however, if only for the gleam that Chippewa, Lundy's Lane and Fort Erie gave to a young but thus far lusterless military tradition. The cost had been high. James Miller, the hero of Lundy's Lane, wrote a friend: "Since I came into Canada this time every major save one, every lieutenant-colonel, every colonel that was here when I came and has remained here has been killed or wounded, and I am now the only general officer out of seven that has escaped."

But now the guns fell forever silent along the forty-mile strait separating New York and Ontario. For the focus of the war had long ago shifted east, where the weight of British arms flowing to the United States from victorious European battlefields was bearing the fledgling American eagle to the earth.

Thundergate

A raid back toward Queenston, commanded by Scott, on July 25 grew into the bloodiest battle of the war. The main armies, each with about three thousand men, met at Lundy's Lane, a half mile east of the falls, forty minutes before sunset. They fought until midnight. Both Scott and Brown were wounded and carried back to Buffalo. General Drummond was wounded. Riall was wounded and captured. Bewildered without the leadership of Brown or Scott, the Americans retired to Fort Erie. The Canadians were too battered and weary to follow. Each army had lost nearly a third of its command: 860 for the Americans, 878 for the Canadians.

The wounds received by Jacob Brown and Winfield Scott were critical. Both were out of the war. General Izard succeeded to the Niagara command. Commodore Chauncey finally consented to carry him and three thousand reinforcements up lake as far as Irondequoit Bay. But the march from Irondequoit to Buffalo gave Drummond's Canadians time for a series of attacks against Fort Erie. Their attack on the night of August 15 took one of the Erie bastions.

The Path of Destiny

Brown's suspicion of an overwhelming British force moving against him was groundless, as he was soon to discover. Sir George Prevost's powerful reinforcements were being concentrated about Montreal for quite another purpose. Upper Canada was General Drummond's nut and he was left to crack it with what troops he had. His subordinate Riall was already on the move, hoping to catch Brown's retreating army by a surprise attack from the flank. His advanced force, which he led in person, was composed almost entirely of veteran Canadian regulars and militia. These troops marched by interior roads toward Niagara Falls through the night of July 24, and soon after daylight they halted to rest on Lundy's Lane, just where that dusty track passed over a small rise in the farm land, close to the famous cataract. They numbered less than a thousand men. The rest of Riall's force, a thousand British regulars and three hundred militia, were in the camp at Twelve Mile Creek (St. Catharines) with orders to march at dawn on the twenty-fifth. Through some confusion of the orders these troops did not set out for Lundy's Lane until noon, giving themselves a long trudge in the afternoon heat.

The information of both sides, usually good and often prompt for that horseback age, was curiously at fault. Neither army knew where the other was and neither could guess the other's intentions. Darkness had covered the march of Riall's Glengarries, New Brunswickers and other Canadians to Lundy's Lane, and there were no British troops on the river road to keep in touch with Brown's retreat. The highway from Queenston to Chippewa ran roughly north to south, separated from the Niagara by a strip of woods and fields half a mile from Lundy's Lane in the west, a handy route for Riall on his right-hook march to Niagara Falls. When his Canadians halted on the rise in the fresh morning light they could hear the boom and see the mist of the great waterfall a mile or so away.

The American army stood beside its tents at Chippewa, invisible three miles to the south, watching the river road and unaware of Riall's approach. General Brown had posted a troop of volunteers at Lewiston, some miles down the American side of the Niagara gorge, to watch the Queenston road across the river and report the expected British march. At last it came and the volunteers sent word up the river. But it was not the march of Riall's men.

When General Drummond heard the bad news of the Chippewa battle he knew that Riall faced the main invasion. Yeo's ships were windbound in Kingston harbor. Drummond set off by road for York with the pick of his redcoats, leaving the rest to come on by ship as soon as the wind changed. On the evening of July 24, just as Drummond's marching men arrived there, four of Yeo's ships appeared at York with the rest of the Kingston force. Drummond's troops joined them, and with a good night breeze the ships arrived at Niagara's mouth at daybreak on the twenty-fifth just as Riall's Canadians reached Lundy's Lane twelve miles up the river.

Colonel Tucker, commanding the fort garrisons at the mouth, could offer only vague news, chiefly that the American army had threatened Fort George and then vanished up the Canadian bank, that Riall was inland somewhere making for Niagara Falls, and that the only American troops on the lower river were a small group at Lewiston. Drummond had been obliged to leave a garrison at Kingston. His own few companies added to the garrisons of Forts George and Niagara made up a force of a thousand, all veteran British regulars. He sent half of them up the American bank with Tucker and the rest along the Canadian side under Colonel Morrison, the hero of Chrysler's Farm. Tucker was to capture or destroy the American troop at Lewiston and then recross the Niagara, joining his force to Morrison's at Queenston on the other side.

All this was done with speed but the two hundred Americans at Lewiston got away, leaving behind a store of tents, baggage, and supplies intended for Brown's army. At Queenston General Drummond rested and fed his united columns after the morning's exertions and sent back a few companies to guard the forts below. With the 850 remaining redcoats he set off along the river road toward the south. The time was well on into the afternoon. Unknown to Drummond, the rear half of Riall's force was only now making its way toward Lundy's Lane by the zigzag tracks of the plateau, so that both of these bodies of British troops were moving miles apart in the fierce July heat but heading for the same destination, the road junction near Niagara Falls where Riall's advance guard stood. The American army was still in the Chippewa camp, an hour's march beyond the junction. Until noon General Brown had no news of the British at all, but then came a message from Lewiston. It said that British ships had arrived at Niagara in the night, that boats were moving up the river, and that redcoats could be seen marching toward Queenston. Soon after this came another hasty report saying that British troops were in Lewiston itself. These were Colonel Tucker's men; but with this scanty information General Brown made a summary of the British movements, partly right and partly wrong - that Drummond had come up the lake to Niagara, joined his troops to Riall's at Queenston, and sent part of his army across to the American bank for a thrust at Brown's communications.

A lesser American soldier, a Hull or a Hampton, would have quit Canadian soil and turned back to the defense of Buffalo. Brown was a fighter and he saw an opportunity. The British army evidently was divided by the river and he had a chance to destroy the force at Queenston before the other got back to support it. He waited for confirming news of a British march up the American bank from Lewiston, but as the afternoon drew on without further word he ordered Scott's brigade to strike at Queenston, ten miles by road below.

Scott moved off between four and five o'clock in the afternoon with his four regiments of infantry, two troops of cavalry, and a pair of field guns, in all 1200 men, the victors of Chippewa and the best troops in Brown s army.The sun was well down the sky but there was no slacking in the heat. As the head of his column reached the house of a Mrs. Wilson, close to the thunder of the falls, Scott had surprising news. A British force of some strength was moving in from the west and had halted on the gently rising ground at Lundy's Lane, which joined the main highway a mile or so ahead. He sent this word back to General Brown, moved on half a mile, and then swung left off the highway, deploying his troops through the fields and orchards facing Lundy's Lane. The rise was before them, not large or high, a mere swelling in the farm land with the lane across its top. Riall had with him 390 Canadian regulars, 500 militia, a troop of the Dragoons, and a field battery; altogether 980 men. When he saw the familiar gray jackets of Scott's brigade moving through the woods and pastures he guessed that he had come upon the main American force. There was no sign of his own rear and he had no knowledge of Drummond's whereabouts. The bloody experience of Chippewa was fresh in his mind, and with a prudence quite foreign to his former nature he ordered his troops to quit the knoll and draw away down the main river road. At the same time he sent a galloper to find his distant rear and change its line of march to Queenston.

As the sun dipped toward Lake Erie, three sweating columns of redcoats and militia stirred the dust of the country roads; one retiring toward Queenston on the main highway, another trudging by a side route to Queenston, and the third (Drummond's) hurrying up the road from Queenston to the junction at Lundy's Lane. On the American part, Scott's brigade remained deployed toward Lundy's Lane and the rise; Ripley's brigade was on the march to them, and Porter's militia and volunteers were among the tents at Chippewa, preparing, in their indolent way, to follow the regulars. The first encounter was between redcoat and redcoat. Drummond on the river road met Riall marching back. Drummond and his men had been on the march smce dawn but the general was eager for battle, and on hearing Riall's news he hurried the combined force up to the knoll before the Americans could get there. Together the British now numbered 1800, more than a match for Scott's brigade until Ripley arrived to support him.

Winfield Scott had expected the usual headlong British attack and it had not come. He was puzzled by the disappearance of the redcoats and their lean militia from the sky line ahead, but soon he saw red tunics and stovepipe shakos on the rise once more, extending their lines to the Queenston road, trundling field guns into position on the crest in their center, and pushing some troops into the woods toward his own left flank. These were obviously defensive arrangements and he decided to attack. He chose the British center and left, sending three of his regiments against Drummond's soldiers at the road junction and ordering Major Jessup with the fourth and the brigade cavalry to make his way along the wooded strip between the main road and the river. The attack went forward at 6:30 P.M. At the road junction it met the levelled volley of the veteran British regiment and a battalion of veteran Canadian militia, while the battery on the rise belched shrapnel and a special detachment fired a stream of Congreve rocket shells. Each of the three gray waves was shattered, each re-formed and came on again gallantly and the fighting was close and fierce, but at last they were thrown back. The loss was heavy. Scott himself was among the wounded. Only Jessup's men escaped damage. Moving behind the screen of orchards and scrub woods between the highway and the Niagara, they were able to place themselves in concealment behind the British left flank. There, for the time, Jessup halted.

Ripley's brigade of bluecoats was now arriving on the scene. It was half past seven, sunset, and the battle had only begun. In the first of the twilight General Brown drew back into his reserve the three torn battalions of Scotts brigade and replaced them in the battle line with Ripley's men. At the same time he ordered Porter's militia and volunteers to move through the woods against the British right flank. These dispositions took time, and night had fallen when the fighting flared up again. Jessup's infantry and horsemen made the first move, springing out of the trees and planting themselves across the road to Queenston at the British rear. Here they captured two noteworthy prisoners; General Riall, badly wounded in the fighting at the junc tion and riding back in the dark, and Drummond's aide. Captain Loring, carrying a message to the British troops on the flank. But Jessup was in a dangerous position without support, and in a short time a British counterattack hustled him off the road with the loss of one third of his men. It was full dark now and although a moon shone fitfully through the smoke, the battle became a blind struggle of regiments and fragments of regiments groping for each other in the bloody angle of the two roads and in the trampled crops and grass on the slope behind.

At nine o'clock the long-missing rear of Riall's force tramped up the road from Queenston just as the battle reached a new pitch. Brown had made a sudden double thrust at the Lundy's Lane knoll. The left attack, made chiefly by Porter's men, shriveled and fell away in a blaze of British musketry and cannon fire. On the right the rest of the U. S. Infantry, stealing up behind a creeper-covered fence, were able to see in a patch of moonlight and to shoot down every gunner in the busy British battery at a few yards' range. They leaped forth, dashed past the guns and over the crest. A fierce clash of bayonets and musket butts followed there, but General Brown, close at hand, brought up two field guns and elements of two other regiments to their support and the British were driven back. The road junction, the knoll and the British battery were all in American hands. At this moment Riall's rear force came up in a darkness made almost solid by the choking powder smoke. The head of the column plodded straight into the old British position at the junction, where it was roughly handled by Brown's alert infantry. The shock of this reception after their dreary nine-hour march was startling, scores of tired and bewildered redcoats found themselves prisoners and it was some time before their own officers and Drummond's staff were able to get the rest with their two field guns into some kind of order in the changed line of battle. But then with his whole force assembled after all the various marches of the day and evening, Drummond led them up the slope.

The Americans on the crest shot hard at the gleam of crossbelts stumbling at them in the murk, but by that time the British bayonets were close. The survivors fell back to their old line in the trees and fields below the lane. They lost their two cannon but dragged away one of the captured British guns, a blind swap in the hurry. Drummond now had a grip on the hillock that nothing could shake. For three hours 1800 British troops had borne all of the American attacks, but with the arrival of Riall's belated column Drummond had drawn into the battle 1910 British regulars, 390 Canadian regulars and 800 Canadian militia, a total of 3 100 men. Against them Brown had thrown the 2700 regulars of Scott and Ripley, Porter's 1350 New York militia and Pennsylvania volunteers, and 150 "Canadian Volunteers" led by the renegade Willcox.

|

|

British Defending A Cannon |

However, Porter had done little fighting and the egregious Willcox had devoted his efforts to raiding farmhouses behind the British lines and capturing unwary stragglers. The burden of the American battle was carried first and last by the regulars in gray and blue and for more than two hours longer these gallant men persisted in attacks up a slope defended by the united British force. Both sides were now exhausted. Water was not to be found in the fighting zone, and after their marches and struggles in the merciless heat of a Niagara summer day and evening the men were choking for lack of it.

Fatigue and thirst finally defeated them all. Toward midnight the battle for a grassy bump on an obscure Canadian country lane came to an end, and as the last shots died away the natural sound of that region could be heard once mo - the boom and rush of Niagara Falls in the sudden quiet of the night. When the British called their rolls in the morning they counted killed 555 wounded and 235 missing, altogether a loss of 878 men. The Americans reckoned their loss at 171 killed, 572 wounded, and no missing, a total of 853. Many of the missing on both sides were prisoners, but after the battle the British found and buried 210 American bodies on the field. The higher proportion of captured British was chiefly due to the misadventure of Riall's second column in the dark.

The higher proportion of Americans killed was due to the blasts of shrapnel from the British battery, to the deadly shooting of the redcoats and militia when Scott made his open attack on the road junction, and to the rocket missiles. In the close nature of the fighting not even generals escaped the bullet storm. Drummond had been wounded, Riall was wounded and a prisoner, and on the American side Scott had a severe wound and so had Brown himself. The pain of Brown's wound forced him off the field toward the last, when he turned over the command to Ripley. According to his dispatches to Washington, he ordered Ripley to march the troops back to the Chippewa camp for food and rest and to return at daylight to renew the battle if the British were still there. But Ripley failed him. Soon after midnight the American troops left the battlefield. Their dead and severely wounded lay where they had fallen. The British soldiers, as Brown had guessed, were too exhausted to pursue. When the fighting ceased they dropped on the ground and slept where they were.

In the morning Ripley broke his camp, burned the restored Chippewa bridge, tossed some of his supplies and tents into the Niagara, and retired up the river to Fort Erie, setting fire to the mills at Streets Creek as he passed.

Oxford Encyclopaedia of Canadian History

Lundy's Lane, battle of. On July 25th, 1814, Jacob Brown, the American general, had concentrated about four thousand men at Chippawa and advancing down the Niagara with part of his force, came in contact with the advance guard of the British under Pearson at Lundy's Lane. Sir Gordon Drummond, the British general, arrived later with reinforcements. Altogether he had in the neighbourhood of three thousand men, but the odds fluctuated throughout the day, sometimes one side sometimes the other being in superior force. Drummond placed seven field pieces on the crest of the rise, and, as at Queenston, the stubbornly fought battle raged around these guns. The battery repeatedly changed hands, and the battle continued far into the night. About midnight the Americans retreated, leaving the British masters of the field of Lundy's Lane. The loss had been heavy on both sides, among the British wounded being Drummond and Riall and among the Americans Brown and Winfield Scott.

Riall: Took part in the contest on the Niagara Frontier; in command of the British troops at the Battle of Chippawa.Drummond: took a prominent part in the War of 1812, from Dec. 1813 to April, 1815 president and administrator of Upper Canada and during this period succeeded in turning the tide of victory to the British forces. Defeated the Americans at Niagara, July 25th, 1814 and followed this up by occupying Fort Erie in November.

A Military History of Canada

The British were not alarmed; they had met this kind of threat before. With fifteen hundred regulars, two hundred militia, and three hundred Indians, Riall headed south and on July 5 met Winfield Scott's brigade at Chippewa. Though he was almost caught drinking coffee at a farmhouse, Scott got away on foot, formed his troops, and waited silently as Riall sent his men forward in a precipitate attack. The British got a devastating surprise. Far from fleeing, Scott's men opened fire and manoeuvred like the professionals they had become. Out of 1500 men, Riall lost over 500 dead and wounded; Scott, with a slightly smaller force, lost 270. Riall withdrew and Brown advanced to besiege both Fort George and Fort Niagara, confident that Chauncey would soon join him. In fact, the American fleet did not appear but Drummond did, with all the British troops he could collect. Brown withdrew and then, worried about his supplies, marched back again. Late on the afternoon of July 25, the two armies clashed at Lundy's Lane, south of Queenston.

It was a soldiers' battle, fought hand to hand late into the night. The British battalions held their ground; brigade after brigade of Americans pushed forward, hidden by dense smoke and then twilight. On both sides, guns were pushed into the front line until they were muzzle to muzzle. British battalions gave ground; Drummond drove them back. Riall was wounded and then captured when his stretcher-bearers blundered into American lines. Brown and all but one of his generals were wounded. So was Drummond. Finally, the Americans had no more reserves. A single British regiment, arriving late, was thrown into the fight. At midnight the exhausted Americans fell back. Drummond forced his men to advance a mile and there the worn-out survivors slept. Next day the exhausted Americans withdrew to Fort Erie. If he had pursued the Americans Drummond might have done fatal damage to the best American army. It was utterly beyond his strength or that of his men.

By August 3 when the British reached Fort Erie, it had been rebuilt and garrisoned. By now, American dominance of Lake Ontario left Drummond with an acute supply shortage. Steady driving rain turned roads into quagmires and converted the land around Fort Erie into a dreary malarial swamp. British morale plummeted. An attack on August 15 was an utter failure. One veteran regiment, DeWatteville's, refused to fight. Others were little better. More than nine hundred British, including some of the ablest of Drummond's officers, were killed, wounded, or captured. Finally, Drummond withdrew to Chippewa but the Americans, too, were demoralized. By late October, they had abandoned Fort Erie. Completed at last, the St. Lawrence made a single voyage escorting supplies and reinforcements to Niagara. It was now Chauncey's turn to take shelter and to wait for his own answer - two monstrous battleships, each bigger than Yeo's new flagship. Surely that was a challenge the British could never match.

The War of 1812

Brown expected Chauncey's ships to bring him supplies and to support his attacks on the British-held forts. But Chauncey feared for the safety of Sackets Harbor, even though he now had two new ships which made his fleet more powerful then Yeo's. As days passed and no help arrived, with his army declining in strength, Brown felt increasingly insecure at the end of a long and exposed supply line. On July 24, he withdrew to Chippawa. Riall decided to follow Brown and so, that night, sent 1,000 regulars under Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Pearson up the Portage Road. The next day, Riall led the rest of his troops in the same direction and soon after, came Drummond leading the 89th Regiment. They were heading towards a hill on Lundy's Lane where it crossed the Portage Road.

When Brown heard about the British advance, he changed his plans. He sent Scott with his brigade back to retake Queenston and prepared to follow with the rest of the army. They would march north along the Portage Road and so meet the British at Lundy's Lane. The outcome of these converging movements was the battle at Lundy's Lane which for several reasons, was both a confused and a prolonged action. The American army advanced in parts with Scott's brigade well ahead.Sections of the British forces were retreating and others advancing because their commanders were not sure of the size of the invading army. Furthermore, the struggle lasted from about 6 p.m. until midnight which meant that much of it was fought in the dark, illuminated only by the flashes of guns and muskets.

As the Americans advanced, Riall ordered Pearson to withdraw from Lundy's Lane. He thought Brown's whole army was attacking and did not know that Drummond was coming to his support. When Drummond arrived at the hill, he saw the American attack developing and immediately recognized that whoever possessed that high ground would have the advantage. He stopped the withdrawal and sent orders to other detachments to hurry to Lundy's Lane. The key of the position was the hill where British artillery was placed to fire at any advancing force. The Americans tried to take the guns by assaulting the flanks as well as the front. Scott's men almost succeeded in getting around the left flank but were driven back after capturing Riall, who had been seriously wounded. The Americans were not strong enough to advance again until the rest of their army arrived.

Brown renewed the attack, and a small detachment captured the British guns. They were soon forced back by British troops attacking with bayonets. The fighting raged back and forth on the hill, neither side able to gain complete control. Dead and wounded soldiers lay where they had fallen on the battlefield. Still the living continued to battle though the light was fading. At some time after 9 o'clock, Colonel Hercules Scott arrived with 1,200 men to reinforce the British line. The British soldiers charged and beat off American attacks. Brown and Winfield Scott were both wounded and withdrew from the battle. Drummond, though wounded in the neck, continued to command. Finally, just before midnight, Brown ordered his exhausted army to retreat to Chippawa. The British troops and Canadian militia were too weary to do anything but fall asleep on the battlefield. Losses were heavy on both sides. Over 700 Americans and 600 British were killed or wounded, making Lundy's Lane the bloodiest battle of the war. It was also a turning point: Brown's advance into Upper Canada was stopped. This was the last invasion of the province.

Neither side can be said to have won the battle (although Brown later claimed he did), but it was the Americans who retreated and who acted like a beaten force. They threw baggage, camp equipment and provisions into the Niagara River, burned Street's Mills, and destroyed the bridge over the Chippawa. Ripley wanted to withdraw all the way to Buffalo, but Brown insisted on holding onto Fort Erie.

When the Americans had captured the fort it had only three guns and was open in the rear. It was too weak to be held against a determined attack. Brigadier General Edmund P. Gaines, who had replaced Brown, set engineers to work to make it stronger. They made a dry ditch and an earth wall right around the rear of the fort. These were covered by guns placed on newly built bastions. By early August the Americans had about 2,200 troops inside this large and now well fortified camp.

After the battle at Lundy's Lane, Drummond did not pursue the Americans. He gave his troops time to recover and waited for reinforcements. Yet, there is a strong possibility that if he had advanced quickly to Fort Erie, even a small force might have driven the Americans across the river. In the last days of July, the British might have captured the fort as easily as the Americans had on the third.

Upper Canada: The Formative Years

Units of the army were well drilled near Buffalo by the young Brigadier-General Winfield Scott, who had already shown the qualities that made him a great commander. Brown's forces, thanks to Scott, were the best American forces to take the field during the war. They crossed the river at the beginning of July and easily took Fort Erie from a small garrison. They intended to push northward toward the lake, then on to Burlington and York. British troops from Fort George and along the lower river rushed south to stem the American advance, General Phineas Riall led them in a reckless assault against the larger American army at Chippawa on the fifth. Rather than their regular blue uniforms, the American regulars wore the grey of the militia.. Rial seeing this assumed an assault would break their ranks and rout their forces. Too late he realized, "They're regulars, by God." On this occasion American regulars proved to be the equal of British regulars and Riall's men were forced back. Brown's plans now received a check, since Chauncey failed to appear with the naval support needed for an advance to the north and west. While Brown waited for Chauncey, and tried to decide what to do next, the commander of the forces in Upper Canada, General Gordon Drummond, hurried to the scene from Kingston to take personal direction of a reinforced army.

The two forces clashed at Lundy's Lane, a mile west of Niagara Falls, on the late afternoon of July 25, and in the next several hours fought the bitterest battle of the entire war. Each side hurled desperate charges against the other. Casualties were heavy in both armies, as Drummond, Riall, Brown, and Winfield Scott were all severely wounded and Riall taken prisoner. By midnight, however, the Americans were too exhausted to make another attack, and fell back leaving Drummond's men in possession of the field. They, in turn, were too exhausted to pursue. The American offensive thrust was now spent and although Drummond's assault on Fort Erie in the middle of August was bloodily repulsed, no further advance of any consequence was attempted. In November the new American commander. General George Izard, blew up Fort Erie and went into winter quarters on the New York side.

|

|

Fort Erie Commemorative Stamp |

The Canadian Encyclopedia

Lundy's Lane, site of a battle fought between American troops and British regulars assisted by Canadian fencibles and militia, took place on the sultry evening of 25 July 1814, almost within sight of great cataract. The action swayed to and fro, as the troops fought each other with reckless abandon in pitch darkness. The British regulars, mainly the Royal Scots and the 8th, 41st and 89th Regiments of Foot, were steadfast in defence and bold adversaries in attack. Sir Gordon DRUMMOND, the Canadian-born British field commander, was wounded and his second-in-command captured. By midnight the British and Canadians held the field and while the hard-fought battle was indecisive, if was the Americans who withdrew and retired towards Fort Erie. Casualties were high on both sides, but the Americans suffered more killed. The battle was the toughest and most bitterly contested of the WAR OF 1812.

|

|

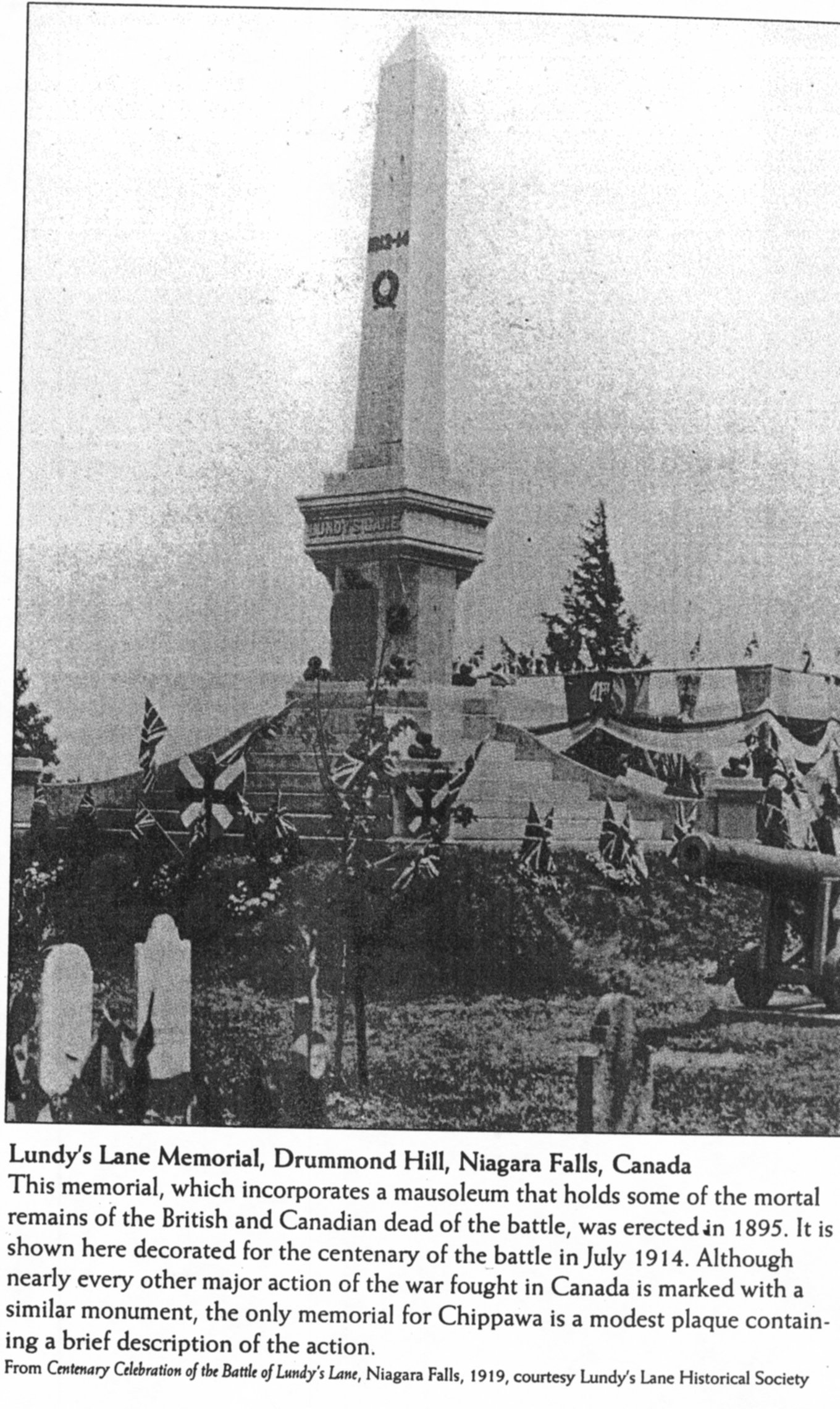

Lundy's Lane Monument |

Wellington's victories in Europe resulted in the release of British forces for service in North America. As a result, the initiative passed to the Canadian side. The Americans returned to the Niagara frontier where after early successes there they were stopped at the murderous battle of Lundy's Lane in July 1814. They won engagement at Chippawa but failing to secure naval support were unable to achieve a decisive victory at the battle of Lundy's Lane and were forced back to Fort Erie.

Where Were the Wounded Treated?

The active services of the troops were continued for a period of nearly three years. The campaign of 1814, which preceded the ratification of peace in the following spring, was rendered important by the successful achievements of the army. Being stationed at York in charge of the general hospital during the greater part of that year's campaign, a favourable opportunity was afforded me of witnessing the state of the sick and wounded who were sent thither from the army. That part of the province, I may observe, which stretches from Fort George to Fort Erie. was the principal field of active operation. After the several actions which were fought in that tract of the country, the wounded were immediately.conducted to the rear as far as Fort George whence they were. shipped on board small vessels, conveyed across the western extremity of Lake Ontario to be landed at York and admitted into hospital. On the evening of the second or third day after an action, they generally reached their place of destination.

After the battle of Chippawa which took place on the 5th of July, a considerable number of wounded were disembarked at York and admitted into hospital. Sufficient accommodation being afforded them the routine of medical duty had not as yet met with any obstruction. The battle of Lundy's Lane, which was fought on the 25th of the same month, being more sanguinary than that of Chippawa, filled the general hospital at York and its adjacent buildings with its numerous wounded. After the latter period, the duty of the medical department not only at York but along the Niagara frontier, became serious and laborious. The skirmishes and casual engagements which occurred during the remainder of the campaign, kept the hospitals more or less filled with wounded till the beginning of winter, when the enemy evacuated Fort Erie and passed over the river Niagara to the peaceful possession of his own territory. Our troops though opposed to a force much greater in number, generally maintained their ground and in almost every encounter had the scale of victory on their side. The task, however, is not mine, either to applaud the well-conducted enterprises of an army or to censure those precipitated measures which in their fatal consequences often obscure the brightest prospects of success.

The general hospital at York, though a commodious building, was deficient in size for the accommodation of the sick and wounded. Its apartments being originally intended for family use were too small for the wards of an hospital, and did not admit of a free ventilation. Neither were the adjoining houses of the hospital which were fitted up for temporary accommodation any way suitable for the reception of the wounded. When in the course of the summer the wounded became so numerous as not to be contained within the general hospital and its outhouses, the church a large and well-ventilated building was dismantled of its seats and for the time being converted into a hospital. The wounded who were admitted into the church hospital had all the advantages of a free ventilation.

|

|

Last Living Veterans of War of 1812 |

The photographer of these last surviving Canadian veterans of the War of 1812 is unknown. It was taken in 1861 in Toronto. These men, who may have seen or even known Brock, along with Native warriors and British regulars, were responsible for the formation of a country called Canada six years later.

[*]While a fancy, embroidered coat was worn for dress, this plainer version was preferred for field use. A major general wore his buttons in pairs with five pairs on each lapel two above each cuff and two on the waist at the coat's back. [**]Caughnawagas meaning "at the rapids" an Iroqois settlement on the St. Lawrence in Quebec. [***]The accuracy of these figures may be questioned particularly the number missing. Desertions were frequent on both sides. ****

A pound of beef and a pound of flour were the principal daily rations of the redcoat serving in Upper Canada, together with alittle butter, rice, peas and two ounces of rum. Boiling hte meat in the messs ketle made it tender enough to chew and yielded a nourishing broth that could be thickened with the rice or peas. The flour baked into bread mixed with water formeed into dumplings called dough boys. Vegetales, fruit, cheese, seasonsings an anaything else required to relieve the awful monotony of the tdiet had to be bought, foraged or stolen. No doubt the quality of the beef varied. At the start of the ar, it came from excellent, fresh local cattle, but as the garrison grew and hedsmen were called from thie pastures to join the militia,

Copyright © 2013 Website Administrator