foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

PEACE ON CHRISTMAS EVE

History is the endless revisiting, reviewing and rethinking the past.

The Treaty of Ghent, which settled the War of 1812, was signed on December 24th, 1814. While this bloody conflict was a life or death struggle for Canada, it was little more than an expensive diversion for Britain. Compared to their own costly life or death struggle with Napoleon, the colonial scrap had only a few colourful incidents: the burning of York, the torching of the Washington's White House, the battles at Queenston Heights, Chippawa and Lundy's Lane. .

It all paled in size and significance to the continental struggle raging in Europe between Britain and Napoleon's Grand Army. Seventy per cent of Britain's entire government revenues were needed to finance the debt incurred fighting the French. When France finally surrendered in April, 1814, the British decided it was time also to end the war with the Americans.

Initially, Britain delayed sending delegates to Ghent, Belgium, the site of the talks, believing that the arrival in America of British troops fresh from fighting in France would unnerve the Americans and strengthen her bargaining position. British successes in the field were offset by the sinkings at sea of numerous British warships by the United States navy, so the prime minister decided to commence discussions.

|

|

City of Ghent |

By the fall of 1814 both countries were intent on seeking a negotiated solution. The United States needed peace at almost any price. Americans had believed they could conduct the war on the cheap and as a result they had no strong national army and relied mostly on state militias. Despite the fact that President Madison described the militia as the "great bulwark of defence and security for free states," militiamen frequently could not be counted on. They were often unruly and undisciplined, each man insisting, for example, on choosing where to pitch his own tent. Pickets were rarely posted and patrols were not sent out at night. Militiamen also flatly refused to fight outside United States territory. Units fought among themselves and things became so bad soldiers were commonly jeered by a critical public. The United States Light Dragoons, a company formed in 1808, had the initials U.S.L.D. on their caps. A contemptuous populace nicknamed them "Uncle Sam's Lazy Dogs."

In an attempt to remedy the mutinous indiscipline of the American military, the secretary of war introduced a Militia Bill, which many feared would lead to conscription. This was a hateful concept and quickly rejected by most Americans, so the bill was dropped. Subsequently, Congress failed to provide the country with either enough men or money to fight the war. British soldiers overran Washington, where in retaliation for the torching of York by American troops, the redcoats burned the Congress buildings, the treasury, the arsenal and the dockyards. A contemptuous and outraged public charged Congress with "sitting in the ashes of its former home." The British also burned the white-painted Aquia sandstone presidential home, the White House. The building was later whitewashed to hide the marks of the flames. President Madison was forced to flee his capital and his wife, Dolly, escaped through Washington in her carriage accompanied by an officer with a drawn sword. She was compelled to spend the night in a tent.

|

|

Dolly Madison |

In a proclamation Madison bemoaned the British occupation of his nation's capital.

In His Own Words

"The enemy wantonly destroyed public edifices, some costly monuments of taste and the arts and others depositories of public archives containing valuable documents of historical instruction and political science of interest to all nations."

The British commander stated it was his avowed purpose "to destroy and lay waste such towns and districts upon the coast as may be found assailable." Madison charged this was being done "on the insulting pretext that it was in retaliation for a wanton destruction committed by the army of the United States in Upper Canada when it is notorious that no destruction has been committed." Of course it had and it was well documented.

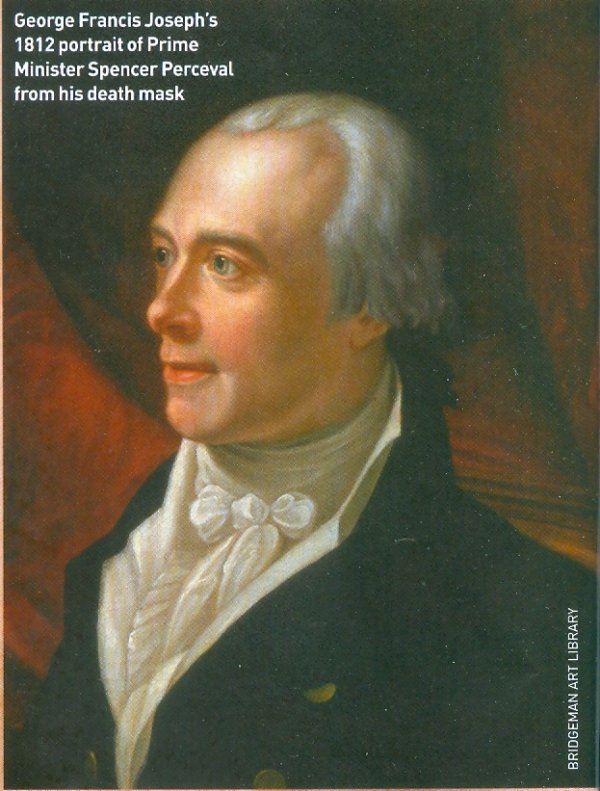

The prime minister at the beginning of this frantic period was Spencer Perceval, who became the only British prime minister ever assassinated.

|

|

Spencer Perceval |

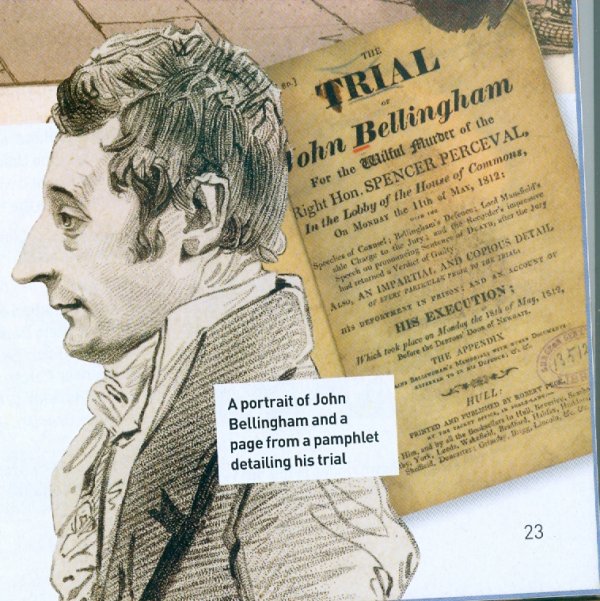

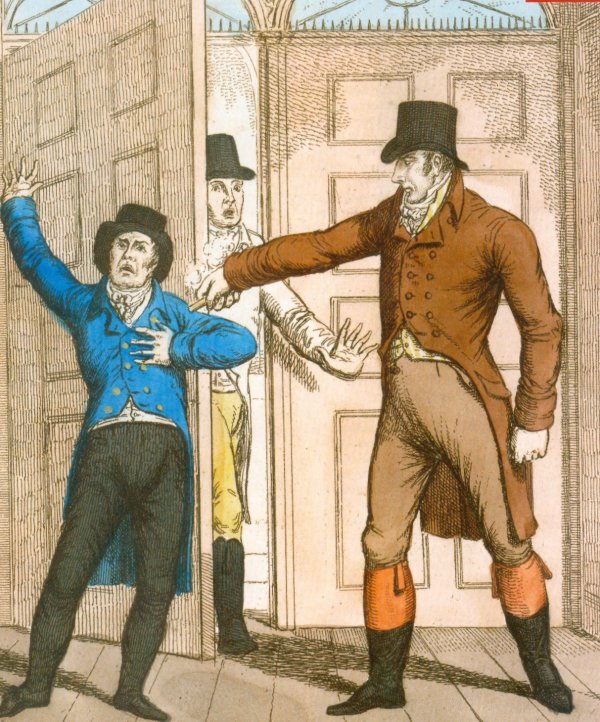

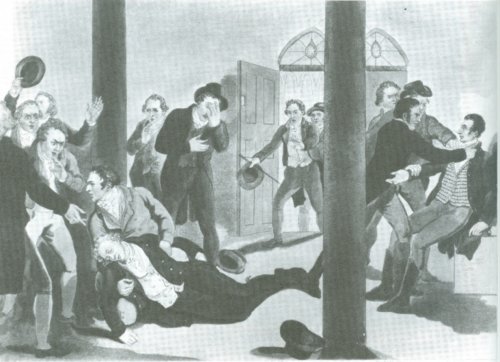

The foul deed was committed by a disgruntled countryman, John Bellingham.

|

|

John Bellingham |

John had just returned from Russia where he had been been imprisoned for five years in connection with some trading problem. Despite his appeals for help, the British ambassador in Russia refused to become involved in Russian justice. When Bellingham had served his sentence, the enraged man returned to England and shot the prime minister at point blank range in the lobby of the House of Commons. The assassin was hanged a week later.

|

|

"I heard a hoarse cry of 'murder, murder' and he exclaimed 'Oh' and fell on his face." |

|

|

Perceval's death was greeted with gaiety as well as gloom and for many, this "savage joy" was profoundly shocking. This horrid act, so common in other countries, was abhorrent to Englishmen. |

Perceval was succeeded by Lord Liverpool who held the office of prime minister for the next fifteen years. Liverpool wanted an end to the war in America as quickly as possible, for the country was already deeply in debt for the European war and would not tolerate any extension of the hated property tax, simply, "for the purpose of securing a better frontier for Canada."

|

|

Prime Minister Lord Liverpool |

While not at the negotiating table, Lord Castlereagh, the British foreign secretary, was ultimately responsible for Britain's negotiations with the Americans. He was preoccupied with what he considered a much more important set of negotiations with other foreign ministers meeting at the Congress of Vienna to remake Europe after Napoleon had been defeated. While in Vienna, Castlereagh kept in touch with events in Ghent through bi-weekly reports on the status of negotiations. On his way to Vienna, Castlereagh was eager to bring the far-off fighting in North America to an early end and win American goodwill.

|

|

Lord Castlereagh, Foreign Secretary |

For six months, peace negotiators attempted to bring about a satisfactory conclusion to the war raging across the Atlantic. The Americans were represented by John Quincy Adams, the American minister to Russia and later sixth president of the United States. He was the first-named member of the group and its supposed head. Adams was thin-skinned, humourless, highly argumentative, quick to take offence and a great hater. He was the president who later became involved in the slave-ship Amistad incident. Other members of the American delegations were: Albert Gallatin, who was Secretary of the Treasury and the sharpest member of the group. He exerted great tact, patience, humour and overall brilliance. James Aston Bayard was a senator from Delaware and in chronic ill-health. Henry Clay, Speaker of the House of Representatives and a prime instigator of the War of 1812 was sent to Ghent to conclude the war he wanted so badly. The lanky, lean-faced, bushy-haired young thirty-seven year old from Kentucky was aggressive and outspoken. The last member of the team was Jonathon Russell, United States minister to Sweden. He was thought by Americans to be a very persuasive negotiator, but was described by his British counterparts as "a quibbling nonentity."

The same description might very well have been applied to the British commissioners. Lord Gambier, an armchair admiral and senior member, who was said to be approaching senility. Dr. William Adams, a so-called expert on international protocol and an obscure Admiralty lawyer, who it was said justified his obscurity. Henry Goulburn was a wealthy, thirty-year old member of parliament for the pocket borough of St. Germains and under-secretary for War and the Colonies. He later became British chancellor of the exchequer [minister of finance]. Gambier was an impressive-looking, silent figurehead and Adams a sputtering, old fool who talked himself and the British delegation into impossible corners. The British government had considered including the Colonial Secretary, Lord Bathurst, on its committee, but unfortunately for Canada, they arrogantly decided to settle this "contemptible little uprising" without including anyone in their delegation as important as a cabinet minister.It never occurred to them to have among their negotiators, a knowledgeable person from Canada, who was very familiar with the coutryside and the contest. Preposterous you say! Well I certainly think so would have been the response..

While Castlereagh was in a conciliatory mood, the London Times advocated a hard approach to negotiations. "Oh may no false liberality, no mistaken lenity, no weak and cowardly policy interpose to save them from the blows! Strike! Chastise the savages, for such they are!" The newspaper tended to reflect public opinion.

Meetings of the negotiators alternated between each party's hotels. The Americans had furious arguments among themselves over the differing interests of the various states. John Quincy Adams disliked Clay intensely and the others avoided Adams if they could. Outside of their official duties, Adams had little to do with his colleagues. "I dined at one. The other gentlemen dined together at four." Adams found the British delegates more agreeable than his own countrymen and spent many happy hours discussing genealogy with William Adams trying to determine whether or not they were distant cousins.

The Americans were superior in every way to their second-rate British counterparts. The latter were mere messengers for the British Foreign Office, their names unknown even to the public they served. As was usual in negotiations between the two countries, the Americans accomplished more at the conference table than they did on the field of battle.

Goulburn dictated the British terms.

(1) They would "discuss impressment" but that is all they would do.(2) They would agree to some revisions of the Canadian boundary.

(3)There would be no renewal of the provision allowing Americans to dry fish on Canadian coasts.

(4) No armed American vessels were to be on or near the Great Lakes and Britain had the right to sail on the Mississippi. (5) Finally, Britain's sine qua non (indispensable condition). The treaty must provide for suitable boundaries for Britain's "Indian Allies." By this the British meant the creation of a buffer state to be occupied by the Aboriginals located between Upper Canada and the United States. This act was intended to set aside a homeland for the displaced Natives was in gratitude for their critically important alliance and to provide a buffer state between Canada and the United States. The land involved included land now comprising: Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin and Michigan.

The Americans were dumbfounded by these demands, which they compared to terms imposed by a conqueror on the conquered, which they firmly reminded the British, they were not. The Americans responded with unrealistic demands of their own. James Monroe, American Secretary of State, asserted that the real price of peace was quite simply the cession of Canada to the United States. If Britain handed over Canada to the United States, the Americans said they would be content. John Quincy Adams declared that this was a reasonable thing to do, since "the U.S.A and North America are identical." This same brash sentiment was expressed at that time in a common 4th of July toast. "To the U.S. Eagle, may she extend her wings from the Atlantic to the Pacific, and fixing her talons on the Isthmus of Darien, stretch her beak to the northern pole."

The British brushed off this ridiculous request and firmly focussed instead on the creation of land for Aboriginal hunting grounds that would not be lost to the plough and the pioneer's axe. In addition, it would provide a buffer state between Canada and the United States. The Americans were incredulous that the British would seriously expect them to recognize as inviolable, land occupied by Indians. They quickly rejected this and declared they were simply not prepared to halt their expansion westward into bountiful lands occupied only by a few bands of natives. Even if a treaty were signed and the peace pipe smoked, the whole process would be meaningless. Their advance was relentless. They compared any attempt to stop the influx of American settlers to "opposing a torrent with a feather." American expansion was "beyond human power to check with any piece of paper." British negotiators knew full well that Americans considered treaties worthless documents before the ink had dried on them. Nevertheless, the Indians were faithful allies who were contributing greatly to their military successes. For this reason it was vital that some provision be made in the agreement for land for these valuable allies.

A critical reason for declaring war to stop impressment, but the British refused to yield on this matter. They believed they had a fundamental right to stop, board and search ships on which they believed British deserters were hiding. They believed that many did so on American vessels, where fleeing Englishemen could claim citizenship and immunity from British seizure. British firmness on this point led to coded messages using numbers being sent to the American negotiators, advising them to drop this item if need be, despite its having been claimed as one of the principal reasons for the American declaration of war.

When the Duke of Wellington defeated Napoleon and the European war ended in April 1814, Napoleon abdicated and agreed to be banished to Elba. When this became known to the American negotiators, Bayard sent this report home to President Madison. "The whole nation is delirious with joy and they indulge in bitter invectives against their remaining enemy, the Americans, whose war was considered an aid to their great enemy, Napoleon. They thirst for great revenge and the nation will not be satisfied without it. To use their own language, they mean to inflict on America, a chastisement which will teach her that war is not to be declared against Great Britain with impunity."

|

|

(Left) Napoleon (Right) Wellington |

Napoleon's collapse freed up large numbers of crack, British regiments for combat in North America, where it was bragged they would, "give `Jonathon' a good drubbing." All during the negotiations, fighting was ongoing and as British and Canadian forces achieved more miliary successes, the U.S. Congress became concerned and dispatched coded messages to their American negotiators, cautioning them to tone down their demands and if need be, simply press for quo ante bellum (return to prewar territorial conditions.) The British countered by calling for, uti possidetis (the retention of all territory in actual possession). He urged Madison to drop the impressment issue which he did.

|

|

Prime Minister Lord Liverpool |

Perceval was succeeded by Lord Liverpool, who held the office for the next fifteen years. When Napoleon was defeated by the Duke of Wellington in 1814, Liverpool said. "I feel most anxious that Wellington should accept the command in America. No other person is equal to the situation. He would restore confidence to the army, place military operations on a proper footing and give us the best chance for peace. I know he is anxious for the restoration of peace with America. "

Wellington said he would go, but doubted he and additional redcoats would be able to impose a victor's peace on the Americans.

In His Own Words

"That which appears to be wanting in America is complete naval supremacy on the Great Lakes. Till that superiority is acquired it is impossible to maintain an army in such a situation. If we cannot do so, I shall do you little good in America and I shall go there only to sign a peace which might as well be signed now."

Wellington certainly wanted peace and endeavoured to ensure it in a secret communication he had with one of the American negotiators. . In a letter to James Callatin, which he marked "Strictly Confidential", Wellington disclosed that in his conversation with the prime minister regarding the war, he had "brought all his weight to bear to ensure peace." Wellington also said that the British negotiator, Henry Goulburn, had "made grave errors" and was called onto the carpet by the prime minister. He did not say what the errors were. For communicating with the enemy in this way, Wellington could have been charged with treason, if the letter had been made public. Fortunately for Wellington, Gallatin destroyed the letter.

The Americans negotiators pressed their arguments with wit, skill and determination, frequently exposing the ineptitude of the British negotiators. Late in December Britain decided to seek peace on the basis of the American position. They did so because the fall fighting had brought unexpected American victories and the British public were becoming increasingly reluctant to bear the cost of further war burdens. Wellington's comments were the final straw. The British government decided to drop their demands and accept the American proposal. Both sides opted for moderation and in an atmosphere of peace decided upon an agreement that resolved very little. The really controversial issues were left to be settled by time and joint commissions.

|

|

Admiral Sir James Gambier and John Quincy Adams shake hands after the signing of the treaty on December 24, 1814, while other negotiators and commission secretaries look on. Henry Goulburn is in the foreground with back mostly turned so that his features and expression are hidden. (Library and Archives of Canada) |

Details of the treaty were finally completed and on Saturday, December 24th at three o'clock in the afternoon, the two commissions met at the British Chartreux, the former monastery where Napoleon had spent one of his honeymoons. At six o'clock with the carillon of St. Bavon chiming its Christmas message of peace and good will in the winter air, the eight men affixed their signatures to six copies of the "Treaty of Peace and Amity Between His Britannic Majesty and the United States of America."

|

|

Signatures & Seals of British and Ameican Negotiators of the Treaty of Ghent |

On Christmas Day the British entertained the Americans at dinner with prime beef and plum pudding and the orchestra played God Save the King and Yankee Doodle followed by toasts to the King and the President. At six-thirty the American negotiators disappeared into the night with the message of good will pealing in their ears and the treaty of peace securely placed in their pockets. An American official named Hughes set off the same evening for Bordeaux to take a copy to the United States. Henry Clay, the American delegation's chairperson, left two days later on a ship he boarded in London; he arrived in Washington before Hughes.

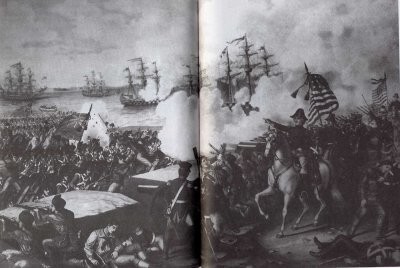

Information moved only as quickly as the wind allowed and horses could run, so news of the signing of the Treaty of Ghent did not reach America in time to prevent the major conflict occurring at New Orleans at dawn on January 8th, 1815. Even though the treaty had not yet been ratified by either country, it is unlikely the battle would have occurred had news of the treaty's existence reached America before it was fought. Tragically, thousands died needlessly, but one man benefitted from the fight - Andrew Jackson. Jackson was a rough-hewn man of the people, who managed to lead despite his well-deserved reputation as a thin-skinned brawler who never met an insult he wouldn't really like to kill someone over. He was criticized politically as a brainless hick who couldn't string two words together. On this field of battle he bashed the British as well as his critics, and his victory at New Orleans had a great deal to do with him becoming the 7th president of the United States. The victory also convinced Americans, that they had won the war.

|

|

Battle of New Orleans |

|

|

Battle of New Orleans |

|

|

Battle of New Orleans |

|

|

Packenham Picked Off |

Information moved only as quickly as the wind allowed and horses could run, so news of the signing of the Treaty of Ghent did not reach America in time to prevent the major conflict occurring at New Orleans at dawn on January 8th, 1815. Even though the treaty had not yet been ratified by either country, it is unlikely the battle would have occurred had news of the treaty's existence reached America before it was fought. American casualties totalled 70, 13 of whom were killed; British killed, wounded and missing totalled 2000.

The British commander at New Orleans was Major General Edward Pakenham, Lord Wellington's brother-in-law. Unfortunately for the troops, Packenham proved to be no Wellington for the battle was a bloodbath for the redcoats, who were directed to make a foolhardy frontal assault on American crack shots, safely sheltered behind earthworks barricades. Packenham rode around on a white horse trying to rally the redcoats as they were being mowed down by the devasting rain of bullets. He was heard to exclaim when he noted that one his brigades was in serious difficulty, "Lost from want of courage." Shortly thereafter Pakenham was shot in the knee and his horse killed. Hit a second time in the arm, he managed to mount an aide's horse with difficulty. Just as he raised his hat in the air and shouted, " Come on brave 93rd," he was struck in the spine. He died as he was being carried to the rear. Considered one of the most lopsided and ludicrous battles of the war if not of all time, the massacre lasted precisely half an hour. Seven hundred of the dead British soldiers were buried not far from where they fell in mass graves. Pakenham's body was shipped home in a casket of rum and buried in the Pakenham family vault.

|

|

Sir Edward Michael Pakenham |

|

|

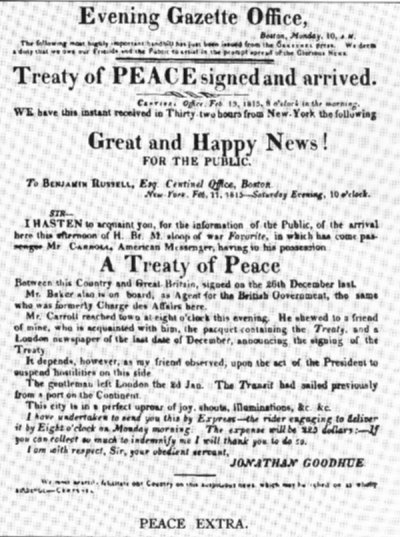

Joyous News |

On February 11th Clay entered New York harbour in the sloop named Favourite clutching a copy of the treaty that was received by American officials with profound relief. President Madison forwarded the treaty to the Senate on February 15th which unanimously ratified and confirmed it on the 17th of February. It was signed and sealed by President Madison on the 18th day of February in the "thirty-ninth year of the Sovereignty and Independence of the United States." A grateful president and Congress designated January 12th, 1815 as a day of "public humiliation and fasting and prayer to Almighty God for His blessings on our arms and a speedy restoration of peace."

The prologue of the treaty containing eleven articles read as follows: "His Britannic Majesty and the United States of America desirous of terminating the war which has unhappily subsisted between the two Countries, and of restoring upon principles of perfect reciprocity, Peace, Friendship, and good Understanding between them, have for that purpose appointed their respective Plenipotentiaries." Article The First"There shall be a firm and universal Peace between His Britannic Majesty and the United States, and between their respective Countries, Territories, Cities, Towns, and People of every degree without exception of places or persons. All hostilities both by sea and land shall cease as soon as this Treaty shall have been ratified by both parties as hereinafter mentioned. All territory, places, and possessions whatsoever taken by either party from the other during the war, or which may be taken after the signing of this Treaty, excepting only the Islands hereinafter mentioned, shall be restored without delay and without causing any destruction or carrying away any of the Artillery or other public property originally captured in the said forts or places, and which shall remain therein upon the Exchange of the Ratifications of this Treaty, or any Slaves or other private property; And all Archives, Records, Deeds, and Papers, either of a public nature or belonging to private persons, which in the course of the war may have fallen into the hands of the Officers of either party, shall be, as far as may be practicable, forthwith restored and delivered to the proper authorities and persons to whom they respectively belong.

Article Two dealt with "prizes which may be taken at sea" which were to be restored.

Article Three dealt with the return of prisoners "after they had paid the debts which they may have contracted during their captivity."

Articles Four through Eight referred any decisions regarding boundaries to commissioners.

Article Nine stated the United States and Britain would "put an end immediately to hostilities with all the Tribes and Nations of Indians with whom they are at war and restore to such Tribes and Nations of Indians all the possessions, rights and privileges to which they are entitled."

While the war itself had little to do with the slave trade, both parties hated the practice and decided to include an article in the peace treaty outlawing the hideous traffic.

Article Ten "Whereas the Traffic in Slaves is irreconcilable with the principles of humanity and Justice, and whereas both His Majesty and the United States are desirous of continuing their efforts to promote its entire abolition, it is hereby agreed that both the contracting parties shall use their best endeavours to accomplish so desirable an object."

Article Eleven stated the Treaty shall be ratified without alteration.

In spite of its failure to settle any of the war's major causes, the struggle, declared President Madison "had been waged with success." It was"just in its origin, necessary and noble in its objects and conducted with pride and the smiles of heaven." Madison described it as a highly honourable event, terminated with "the most brilliant successes" as a result of the "patriotism of the people, the public spirit of the militia and the valor of the military and naval forces of the country." Madison was attempting to put a good face on near defeat. Disregarding the fact that none of the causes was cured by the war, many Americans lauded the president who had brought them a triumph. Madison was miraculously transformed from the cause of the crisis to the leader of a victorious people who had "brought Britain to her knees." Some historians cite only The Star Spangled Banner, the American national anthem, as the main outcome of the war. It was written as the British bombarded Fort McHenry over which 'Old Glory' still flew.

By and with the advice and consent of the Senate of the United States the treaty, "an event highly honourable to the nation," was unanimously accepted and signed by President Madison on February 18th. Post riders raced throughout the nation spreading the news. The peace settlement was well received in Britain where it was ratified on December 28th by the British Prince Regent. News of this reached Lord Castlereagh in Vienna on New Year's Day. Castlereagh was anxious to recall the British fleet from America so that he could concentrate it and a mobile invasion force on the European side of the Atlantic.

Despite the fact that the peace treaty had been signed but not sealed, the lopsided victory resulted ever after in the proud boast by Americans that they had won the War of 1812. Andrew Jackson commanded the victorious American forces and used his fame as a fighter to win an election and become the 7th American president of the United States in 1829.

|

|

Andrew Jackson |

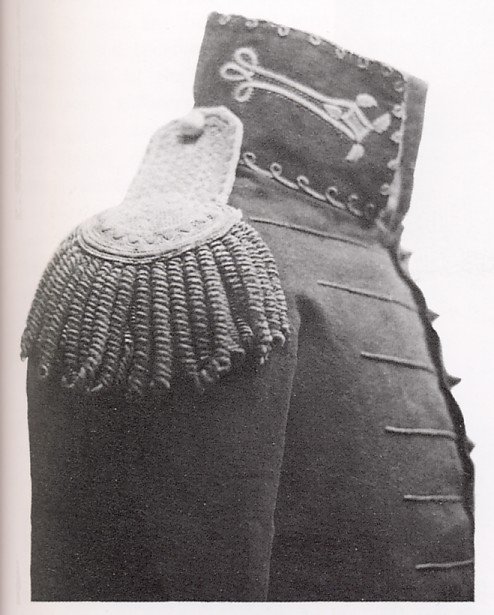

|

|

Detail of the coat worn by Andrew Jackson at the Battle of New Orleans |

In 1815 any likelihood of a lasting Anglo-American peace seemed remote. Many points of friction continued to exist between Canada and the United States and for this reason John Quincy Adams considered the treaty little more than a truce because "nothing was adjusted, nothing settled." It was suggested that Canada be given back to the Natives since "it was fit for nothing but to breed quarrels."

When judged by its terms the Treaty of Ghent settled very little but in fact there were significant results. The withdrawal of British military might resulted in Native warriors dropping their tomahawks. The power of the Aboriginals in the Northwest had been shattered thus removing the grievance that motivated American craving for Canada. They were free now to flow into the west south of the 49th Parallel at the expense of the Aboriginals and the Spanish.

Under Article 9 the Americans agreed to end the war against the Natives and "forthwith restore to such tribes all possessions which they enjoyed in 1811 prior to such hostilities." In fact, Andrew Jackson directed his men to keep the "sullen, demoralized Indians" moving west. Since the main British army had returned across the Atlantic there was no military might great enough to enforce Article 9. Disputes over blockades and impressments ended not because of American valor and victories but because the European war had ceased and trade restriction were no longer necessary.

For Canadians the treaty confirmed that Canada had won the "sprawling and sporadic war" because the Americans had failed in their attempt to conquer Canada. It inspired in Canadians a new sense of patriotism, great pride in the accomplishments of its militia and an ill feeling towards the republic to the south that was slow in fading. The peace treaty meant that the United States accepted Canada as a legitimate national entity and not simply as an unresolved problem inherited from their War of Independence to be settled when they were strong enough to do so. Peace was built on the foundation of a friendly, common sense relationship. After the treaty was signed, John Quincy Adams said, "I hope this will be the last peace treaty between Great Britain and the United States." It was.

|

|

Henry Asquith |

One hundred years later in 1914 the British Prime Minister, Henry Asquith recorded in his diary that he had attended a meeting at Mansion House in London. Its purpose was to plan celebrations for the anniversary of 100 years' of peace "between us and the Yankees." Asquith described the meeting as a "pretty dismal affair" with none of the speakers in attendance able to rise above the "level of platitudes." As it turned out this did not really matter for the party that was planned to celebrate a century of peace between His Britannic Majesty and the United States of America never took place. Another conflict, the First World War, the war to end all wars, had just begun and the city of Ghent, which was the proposed site of the peace celebrations, came under fire from German guns. Instead of a party the two countries just exchanged messages of goodwill.

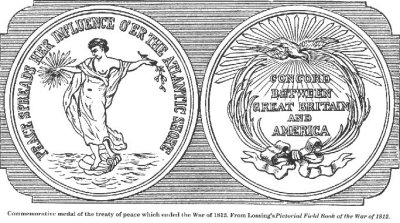

|

|

PEACE SPREADS HER INFLUENCE O'ER THE ATLANTIC SHORE |

For all its real or imagined faults, the Treaty of Ghent lasted and proved to be an enduring and decisive document. Following the war, both sides withdrew to prewar positions without either declaring success or a defeat. Neither side could refer to the terms of the treaty as a triumph or a trouncing.

As the date October 13th, 2012 approaches, marking the 200th Anniversary of the Battle of Queenston Heights, various ways of celebrating this significant event are being proposed in both Canada and the United States of America.

National Post, Tuesday, October 20, 2009 Proposed U.S. postage stamp would pay tribute to former Canadian foes.Eight U.S. senators calling for a special stamp to mark the War of 1812's upcoming bicentennial have given a surprising nod to the historic enemy - Canada - as part of their pitch for the commemoration. Among the reasons cited by the Senators to convince the U.S. Postal Service to pay tribute to the 1812-14 conflict is that the war "was significant in the formation of Canada and the Canadian identity." The Senators, led by Michigan Democrat Carl Levin, do make reference to the war as a "defining effort for the United States in securing and defining its boundaries." They emphasize how the battles led to the 1814 Treaty of Ghent and a "lasting peace" with Britain and Canada. Mr. Levin told Canwest News Service: "The war of 1812 played an important role in defining the character of both the United States and its resolution provided the basis for lasting U.S.- Canadian relations."

Copyright © 2013 Website Administrator