foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

TWO NATIONS

History is the aspirations of humanity..

In 1783 the Peace of Paris ended the American Revolution. The treaty was approved by the British parliament in spite of the fact that many of its members believed concessions had been made to the Americans "greater than they were entitled to, either from the actual state of their respective possessions or from their comparative strength." Britain's generosity towards the Americans was not reciprocated. There was no way George Washington, who called Loyalists "internal foes" and said they had represented "conspiracy, sabotage and organized armed resistance," was even going to consider compensating them.

A contemporary observer was more sensitive to their situation and paid them this fine tribute

"How sad has been the fate of all those truly meritorious but unhappy men, the American Loyalists of every denomination! True to their king, faithful to their country, attached to the laws and constitution, they have continued firm and inflexible in the midst of persecutions, torments, and death. Many of them have abandoned their homes, their friends, their nearest and most tender connections, and encountered all the toils of war, want, and misery, solely actuated by motives the most disinterested and virtuous. In short they have undergone trials and suffering, with a determined resolution and fortitude, unparalleled in history; and have submitted even to death sooner than stain their integrity, honour, and principled loyalty with the odious guilt of rebellion against their king men, not only of their possessions, and the society of their friends and relations, but of that apparently established felicity and affluence, which they themselves, and their posterity after them, had the prospect of enjoying for ages to come. No compensation can be adequate to the loss sustained by these deserving individuals"

|

|

In March 1776 Sir William Howe directed the evacuation from Boston of Loyalists "whose Hurry and Confusion was dreadful to behold." |

The Loyalists remained the losers, who in the words of one historian, were simply ill-fated individuals who had wagered on the wrong horse. Peace left the British government to shoulder alone the tremendous task of re-settling thousands of these "un-American" Americans, many of whom migrated to Canada to start a new life.

|

|

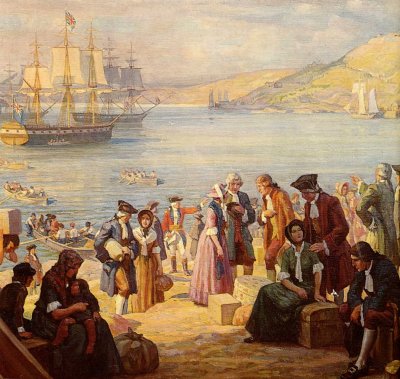

Loyalists Landing in Canada |

They came by wagon, ship and shank's mare, lugging along with them whatever clothes and furnishings they could carry. Some fortunate few were able to bring precious treasures like delicate tea cups and fine table clothes, cherished reminders of a life that had gone forever. Hundreds of wagons rolled northward across country and traversing rivers.

"Nineteen covered wagons conveying families came to settle in the vicinity of Lincoln county. The way they cross the river is remarkable. The body of the wagon is made of close boards; they caulk the seams and by shifting off the body it transports the wheels and the family to the other side where the vehicle is then put together again."

|

|

Covered Wagon |

|

|

Early Loyalists Leaving Loaded |

The Loyalists were persona non grata in their native land. They were labelled opportunistic renegades, who supported the crown over their country solely for personal gain. Among their most fervent detractors, were Presbyterian ministers whose Sabbath sermons denounced with "thunder and lightning" British oppression. They condemned Loyalists for their failure to support "their country" Because Loyalists were considered treacherous in opposing their homeland, one minister went so far as to rebuke them, taking as his text, Judges, Chapter V, Verse 23:

Curse ye Meroz, said the angel of the Lord

Curse ye bitterly the inhabitants thereof;

Because they came not to the help of the Lord

To the help of the Lord against the mighty.

|

|

Bible |

The Royal Raiders were astounded when all of Britain's power and might failed to subdue the rebels' ragtag army, which was ridiculed on occasion, even by its own commander. "Good Heavens," cried George Washington flinging his hat to the ground and lashing out with his cane at officers and men fleeing from the oncoming redcoats, "Have I such troops as those!" A Chaplain in Concord, Mass. noting the tight discipline that was put into effect in Washington's army wrote; "New lords, new laws. The strictest government is taking place and great distinction is made between officers and men. Everyone is made to know his place and keep it or be immediately tied up and received not one but 30 or 40 lashes." Washington turned down the requests of blacks seeking freedom to fight in the revolutionary army, so many joined the British forces which promised freedom.

Washington was a taciturn type who did not encourage affection and was criticized for his harshness and rigid discipline. One man on a dare called him George and drew an icy stare. His wife called him 'My old man' and some of the frontiersmen in his ranks knew him as 'Old Hoss.' Washington rarely smiled, a fact that doubtless had to do with his defective teeth, for he had dental troubles for most of his life. "He wore the teeth of pigs, cows, elk, etc., in his dentures and also used human teeth. One pair of his false teeth set in lead weighed three pounds."

In the beginning it was bragged by some in Britain that "the city of London alone was a match for ten Americas." But the war did not follow its script. Wars rarely do. It held nasty surprises for both sides but the biggest was for Britain. The unthinkable happened - Britain lost the war. It did so for a number of reasons including lack of leadership, lack of support in Britain for an unpopular war and under-estimating then alienating with arrogance their adversary.

Logistics were also a big factor. Keeping a large force far away supplied with equipment was difficult for Britain, particularly when its navy had to station ships in European waters to watch Britain's biggest water-borne enemy, France. The British military also made ineffective use of Loyalist forces. Finally, Britain was simply faced with an excess of enemies. By 1780 Britain was at war with virtually the whole world. In addition to the France and Spain, England was at war also with the Holland whose powerful fleet provided great support for the rebels. Russia, Prussia, Denmark and Sweden were leagued against Britain in "armed neutrality."" Taken together this resulted in Britain's defeat, news of which was "the most melancholy message Great Britain ever received."

|

|

|

The final peace treaty contained two articles pertaining to the Loyalists.

Article V:

"All persons whether borne arms or not shall have free Liberty to go to any part or parts of the 13 United States and therein remain for twelve months, unmolested in their endeavours to obtain the restitution of such of their Estates, Rights & Properties as may have been confiscated."

They were to "meet with no lawful impediment in the prosecution of their just rights." The American Congress recommended to the 13 States that this be allowed and that state legislatures act to restore Loyalist belongings. Instead, some states quickly passed laws that made all demands for the return of confiscated property wholly inadmissible. New York passed a resolution which cancelled all debts due Loyalists, providing one-fortieth of it was paid into the state treasury.

Article VI:

"There shall be no further confiscation made nor any Prosecution commenced against any Person or Persons for or by Reason of the Part which he or they may have taken in the present war and that no person shall on that account suffer any future loss or damage either in his person, Liberty or Property."

Despite these words, the winners were in no mood to be magnanimous. The 13 states not only completely disregarded the treaty's terms, they passed punitive laws. Most of these laws, according to one honest American observer, were only tools "of the most sordid interest. One patriot wishes to possess the house of some wretched Tory, while another fears the Tory as a rival in his trade or commerce, and a third wished to get rid of his debts by shaking off his Tory creditor." One of the few American leaders who opposed these retaliatory laws was Alexander Hamilton who declared that penalizing former Loyalists as a class violated both "natural justice and the peace treaty." Hamilton's words fell on deaf ears. Woeful consequences befell any Loyalists who dared to venture back to collect compensation. Appeals to the courts were useless for Loyalists soon learned that they could expect not "a shadow of justice." Instead of justice, equity and conciliation which the peace treaty said, "should universally prevail," Loyalists found only injustice, reprisal and rancour.

|

|

|

Loyalists fled to New York, the last British bastion in the 13 Colonies, from where they were transported to safety and a new settlement. Those who had ample time retreated with dignity, carrying the family's prized possessions with them. Most fled with little more than the clothes on their backs. On arrival in the new land they were herded into camps where they survived on government rations and dreams of a new life in a new land.

As a point of honour, Sir Guy Carleton refused to evacuate the British troops from New York until he was satisfied that every last Loyalist who desired the protection of the British flag had embarked on his ships. This included black slaves, who had fought for Britain in exchange for freedom, as well as any who had escaped from their rebel masters, one of whom was President George Washington. He owned 100 slaves, two of whom escaped. The slaves were silent members of the social order who had no voice and few dared speak out on their behalf. Carleton recognized this and was reluctant to leave any slaves to the harsh treatment of their outraged masters.

In His Own Words"I should show an indifference to the feelings of humanity as well as to the honour and interest of the nation I serve, if I were to leave any of the Loyalists who are desirous to quit the country, a prey to violence they conceive they have so much cause to apprehend."

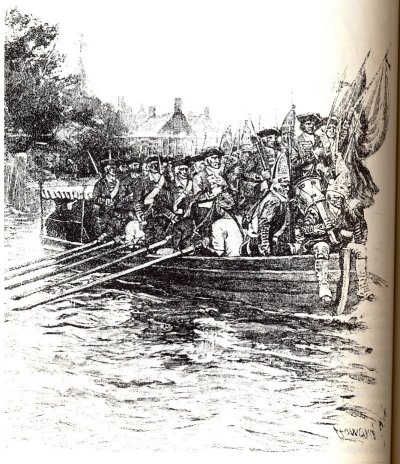

The last of the Loyalists shook the dust of New York from their shoes on 25th of November. On that cold, bright, autumn day the final act of the long drama drew to a close. Since most of the Loyalists had already departed the crowds that thronged the streets were chiefly triumphant patriots who watched disdainfully the departure of traitors they had vanquished.

|

|

Last British Soldiers Leave New York, 1783 |

From aboard the ship Ceres Carleton wrote his last dispatch regarding the evacuation of redcoats and Loyalists from American soil on November 29th,1783. As he did so he ended one of the most dramatic accomplishments in the history of the British Empire.

|

|

|

Compensation never came from the victors for the states flatly refused to reward traitors who had turned against their own country. American negotiators stubbornly refused to restore Loyalist property, remarking to their British counterparts, "It is strange that you should insist on our rewarding the people who have plundered, burned and cut our throats. If you think they are so very deserving why don't you reward them yourselves? It would be very hard for you to oblige us to reward them even if you had conquered us; please remember that you have not conquered us."

Loyalists deeply resented the failure of the British government to press their case more strongly. Their sentiments were summed up by one disgruntled Loyalist. "Tis an honour to serve the bravest of nations, And be left to be hanged in their capitulations."

Many recognized the great sacrifice the Loyalists had made and spoke out in support of their cause. "In ancient or modern times," said one lord, "there cannot be found an instance so shameful as this desertion of men who have sacrificed all to their duty." One Loyalist protested in a newspaper named Rivington's Gazette that "even robbers, murderers and rebels are faithful to their fellows and never betray each other."

It is little wonder Loyalists arrived in Canada angry and embittered. Patriotism had been dearly bought by these loyal royals labelled "one of history's complete losers." It seemed that after sacrificing everything they had been shamefully deserted, left to wander the wilderness of Ontario facing the perils of the present and the bleak uncertainty of the future. Initially, as a result of their remoteness and the miserable conditions in which they were living some Loyalists lamented their decision to abandon home and hearth and expressed their loneliness and frustration on arrival in this new land. One such soul bitterly lamented her fate.

In Her Own Words

"I climbed to the top of Chipman's Hill and watched the sails disappearing in the distance, and such a feeling of loneliness came over me that although I had not shed a tear through all the war, I sat down on the damp moss with my baby on my lap and cried bitterly. All our golden promises vanished in smoke. We were taught to believe this place was not barren and foggy as had been represented but we find it ten times worse. We have nothing but His Majesty's rotten pork and unbaked flour to subsist on. It is the most inhospitable clime that ever mortal set foot on."

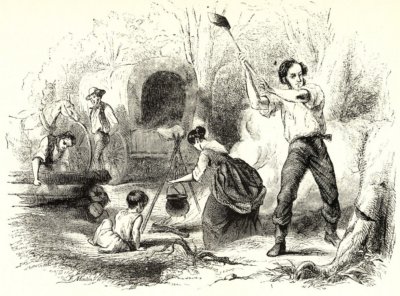

Others, however, were ready to forget the trials and tribulations and get on with the business of felling trees, planting crops and beginning a new life in this new land, free at last from the fear of menacing mobs.

|

|

A Loyalist Family Starts Anew (6) |

In Her Own Words

"There was no floor laid, no windows, no chimney, no door, but we had a roof at least. A good fire was blazing and Mother had a big loaf of bread and she boiled a kettle of water and put a piece of butter in a pewter bowl. We toasted the bread and all sat around the bowl and ate our breakfast. Mother said: 'Thank God we are not longer in dread of having shots fired through our house.' This is the sweetest meal I ever tasted for many a day."

|

|

|

Belatedly the British government rose to the challenge. Once the Loyalists had sworn the oath of loyalty and their land had been allotted, the government began to reward the zealous fidelity of the Loyalists. Clothing was distributed as well as axes, hoes and seeds to sow. Governor Simcoe was directed to provide for the Loyalists by giving them "certain Gratuities and furnishing them with necessaries & Implements of Husbandry."

|

|

|

Each group of five men was given one saw and one firelock rifle, as well as five pounds of powder and four of ball. Provisions for a month were apportioned and more was promised. With this and little more, the Loyalists never looked back on their ungrateful country, but set off to find new lands and a new life in Canada. The Royal Word had been pledged that "Loyalists U.E." were to have their land patents free of expense to them. Simcoe lost little time in doing everything in his power to implement, "His Majesty's benevolent Intentions" relative to the Loyalists and their land. He was determined "to assist them to the utmost of our Power."

Most of those who arrived on October 3rd, 1792, wished to go immediately to their own lands instead of staying in the interim accommodations which were offered to them. Plans had been made for them to settle at York, but because of the lateness of the season many set off for lands in the neighbourhood of Kingston. A surveyor was directed to locate them there "so that they might become serviceable settlers in that exposed Frontier."

|

|

Loyalists Along The St.Lawrence River, 1784 |

Who was a Loyalist? One rebel defined a Loyalist as "a Tory whose head is in England, whose body is in America and whose neck is out to be stretched." Only one group merited the designation United Empire Loyalist. They had to be residents of the American colonies prior to the revolution and have served the British cause during the war. Having lost their property because of loyalty, "that gloried in the honest pride of having withstood all the tempests of revolution," they must have fled to Canada by the year 1789. They were a fair same of English-speaking provincials in North America, a cross-section of rich and poor, literate and uneducated, town and country, seaboard and frontier.

The Americans did not consider the revolution a fratricidal fight. It was no civil war to them. They saw it as a national uprising against British oppressors. In his appeal for volunteers to defend the 13 colonies, Patrick Henry asked, "Is life so dear or peace so sweet as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery? Forbid it Almighty God! I know not what course others may take but as for me, give me liberty or give me death." In this emotionally charged atmosphere any who opposed the fight for liberty were despised as seditious, self-serving Tories. According to one American balladeer, Tories were "so vile a crew the world ne'er saw before."

Loyalists were reviled also by early American historians, who considered them self-righteous reactionaries who opposed their country's noble struggle. Nearly a hundred years passed before a serious attempt was made to discuss Loyalists as less than diabolical. Some American historians may still consider the Loyalists as turncoats out of touch with their times. A paper published by an American historian in 1961, asserted that Loyalists comprised one-third and Patriots two-thirds of the politically active population. While observing that many British-born settlers were loyal to their homeland, the writer argued that Tories were more numerous among the non-British colonists. According to him, these non-English speaking people believed the British parliament was more likely than the American Congress to safeguard their cultural position in a society dominated by aggressive Anglo-Americans.

Historians have questioned why those who were the Loyalist leaders could not have exercised more influence over the behaviour of Americans. They were unable to do so apparently because it was too late for Tory intellectuals to influence their American countrymen. By the time they finally attempted to do so, there was already "an alarming uniformity of outlook in America."Many Americans had already decided where their loyalties lay, and in such a society the Tory point of view was considered irrelevent. American patriots were simply not prepared to listen to Loyalists.

Britain was determined to recognize the courage and loyalty of its faithful citizens, and Sir Guy Carleton put word to his country's wish when at the Council Chamber at Quebec on Monday, November 9th, 1789, His Lordship intimated to the Council that it was his wish

In His Own Words"to put a Marke of Honour upon the families who had adhered to the Unity of the Empire and joined the Royal Standard in America before the Treaty of Separation in the year 1783."

This date was later extended to 1789. Land boards were directed to preserve a registry of all such persons, "to the end that their posterity may be discriminated from future settlers." Land boards failed to follow this order explicitly, and when he arrived in Upper Canada, Governor Simcoe was shocked to discover that the regulation was largely a dead letter. No accurate registry had been kept. Prior to his departure from Upper Canada, Lieutenant-Governor Simcoe issued the following proclamation.

Upper-Canada BY HIS EXCELLENCY JOHN. G. SIMCOE, Esq. LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR AND MAJOR GENERAL OF HIS MAJESTY'S FORCES, &c.&c.&c.

PROCLAMATION Whereas it appears by the minutes of the Council of the late Province of Quebec, dated Monday the ninth day of November, 1789, to have been the desire of his Excellency Lord Dorchester the Governor-General "To put a mark of honour upon the families who had adhered to the Unity of the Empire, and joined the Royal Standard in America, before the treaty of separation in the year 1783," and for that purpose it was then Ordered by his Excellency in Council, that the several Land Boards should take course for preserving a registry of the names of all the persons falling under the description aforementioned, to the end that their posterity might be discriminated from the then future settlers in the parish registers and rolls of the militia of their respective districts, and other public remembrances of the Province, as proper objects, by their persevering in the fidelity and conduct so honourable to their ancestors, for distinguished benefits and privileges; but as such registry has not been generally made; and as it is still necessary to ascertain the persons and families, who may have distinguished themselves as above mentioned; as well for the causes set forth, as for the purposes of fulfilling his Majesty's gracious intention of settling such persons and families upon the lands now about to be confirmed to them, without the incidental expenses attending such grants: - NOW KNOW YE, that I have thought proper, by and with the advice and consent of the executive council, to direct and do hereby direct all persons, claiming to be confirmed by deed under the seal of the province in their several possessions, who adhered to the unity of the empire and joined the royal-standard in America, before the treaty of separation in the year 1783, to ascertain the same upon oath before the magistrates in the michaelmas quarter-sessions assembled, now next ensuing the date of this proclamation, in such manner and form, as the magistrates are directed to receive the same; - and all persons will take notice that if they neglect to ascertain, according to the mode set forth, their claims to receive deeds without fee, they will not be considered as entitled, in this respect, to the benefit of having adhered to the unity of the empire and joined the royal standard in America before the treaty of separation in the year 1783.

Given under my hand and seal at arms, at the government house at York, this sixth day of April, in the year of our Lord, one thousand seven hundred and ninety-six, and in the thirty-sixth year of his Majesty's reign.

JOHN GRAVES SIMCOE

GOD SAVE THE KING!

E.B. LITTLEHALES.

By his Excellency's Command

A list known as the "Old U.E. List"was compiled using land board registers, provision lists, muster lists and names from registrations made under oath. The title United Empire Loyalist results from the phrase "Unity of Empire," and is applicable only to those whose ancestor's name is inscribed on this Deeds free of fee were distributed to these distinguished settlers, and according to one surveyor, who inspected the land allotted to these patriotic pioneers, it should "make the Loyalists the happiest people in America." The original founders settled in a country whose magnificent forests confirmed that the soil was rich, and of the highest quality. One tree is reported to have had a trunk eleven feet in diameter. These giants confirmed the soil's fertility, but the huge trees also frustrated the farmers, who had to clear the land of thickly forested acres of pine, hemlock, oak and maple. The hardy settlers were up to the challenge, and by hard work, determination and perseverance they prevailed.

Mrs. Simcoe, wife of Lieutenant-governor John Graves Simcoe, described how they undertook the task

In Her Own Words"The way of clearing the land in this country is cutting down all the small wood, pile it and set it on fire. The Heavier Timber is cut through the bark five feet above the ground. This kills the trees which in time the wind blows down. The stumps decay in the ground in the course of years, but appear very ugly for a long time, though the very large, leafless white Trees have a singular & sometimes picturesque effect among the living trees. The settler builds a log hut covered with bark & after two or three years raises a neat House by the side of it. This progress of Industry is pleasant to observe."

Evidence of the success and satisfaction of Loyalists in Upper Canada was attested to by an English visitor passing through Johnston (present-day Cornwall), on his way to see Niagara Falls in 1785. He was most impressed with what he saw. "The setting of the Loyalists is one of the best things George III ever did. It does one's heart good to see how well they are all getting on and seem to be perfectly contented with their situation." When Mrs. Simcoe travelled through the country in 1792 she too was struck by the neatness of the farms and the high quality of the wheat. She commented on it in her diary, "I observed on my way thither that the wheat appeared finer than any I have seen in England and totally free of weeds."

|

|

|

One loyalist who settled in the Niagara Peninsula boasted, "This is one of the finest countries in the world for a farmer who will be industrious. You would be astonished to see people from all parts of the States coming by land and water. Two hundred and fifty wagons at one time with their families on the road, something like an army on the move. The goodness of the land is beyond description. There are the best of crops this season (1800) that I ever saw." Another grateful immigrant commented, I very often think of the slave in England and the empty bellies. A man is drove to be dishonest in England but here there is no call to be."

A commissioner who had come to Canada to investigate Loyalist claims for losses suffered during the Revolution visited Upper Canada in May 1787 and was most impressed with what he saw. "The soil is excellent and the climate is good. They are mostly thriving."

"Not drooping like poor fugitives they came

In exodus to our Canadian wilds,

But full of hearts and hope, with heads erect

And fearless eyes victorious in defeat."

Copyright © 2013 Website Administrator