foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

SIMCOE

&

THE BIRTH OF UPPER CANADA

History shapes the world in which we live.

The Quebec Bill, which became the Constitutional Act of 1791, was introduced in the British House of Commons by Prime Minister William Pitt. The Bill's birth resulted from the influx of Loyalist Americans into Canada from the 13 Colonies following the American Revolution. These supporters of the sovereign - called among other things Tories by the rebels and Loyalists by the monarchists - sought safety in Quebec from persecution and punishment at the hands of the vindictive victors.

The society on the St. Lawrence was French and foreign and it was not long before the emigres were appealing to the Imperial Parliament for the rights of English people - English laws and freehold land tenure. After some time the government responded to their pleas by approving the Constitutional Act of 1791. John Graves Simcoe was a Member of Parliament when debate on the bill took place and as he listened to the illustrious statesmen and their spirited discussions, little did he realize that his name and fame would be forever linked to one of the colonies to be created by the Act.

|

|

House of Commons, 1792 |

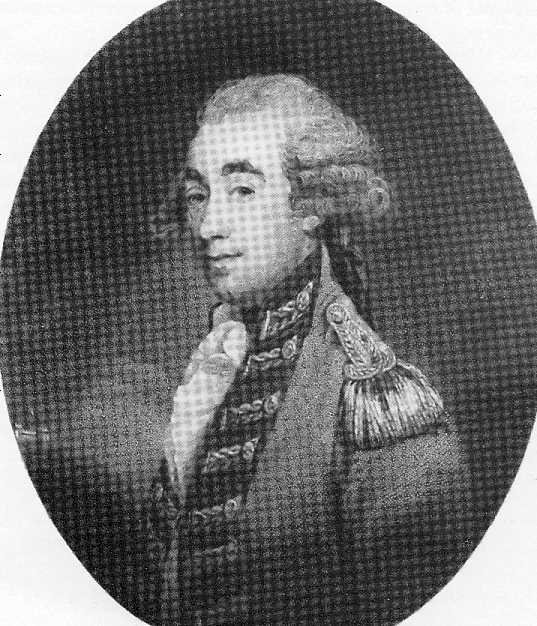

On October 20th, 1789 Lord Grenville transmitted the first draft of the Quebec Bill to Lord Dorchester in Quebec for his comments and suggestions. Along with his recommendations regarding the bill, Dorchester submitted the name of Sir John Johnston, then Superintendent of Indian Affairs, "as the properest person" for the position of lieutenant-governor of Upper Canada. Grenville informed him that he "had already nominated Lieutenant-Colonel Simcoe" for this position and the King had given his approval.

|

|

Lord Dorchester |

In a letter to Under Secretary of State Sir Evan Nepean, dated December 3, 1789 Simcoe had offered his talents to the government.

In His Own Words"I should be happy to consecrate myself to the Service of Great Britain in Canada in preference to any situation of whatever emolument or dignity."

During consideration of the Quebec Bill in the House of Lords on May 30th, 1791 Lord Rawdon, a personal friend of Simcoe, spoke in opposition to the bill but he enthusiastically supported Simcoe for the position it would create.

In His Own Words"The gentleman to be honoured with the appointment of Governor is of all others the fittest and most to be wished for by the country. His intelligent mind, his generous and liberal manners, his active spirit and peculiar abilities for that situation rendered him in an eminent degree the properest person that the Ministers could have selected for that appointment." Rawdon said Simcoe's appointment would rebound to their honour and credit. If, said Rawdon, Canada were to be governed under the present bill, it would be well for Britain and well for Canada that Colonel Simcoe was the Governor. He hoped and trusted that the Ministers would make it worth Simcoe's while, particularly since Simcoe, "by undertaking this arduous and not altogether agreeable task was giving up a situation of ease, respectability and affluence at home."

Simcoe volunteered his services again in 1790 when he offered to raise a corps of 12 companies under his colonelcy in Canada. In 1791 he submitted a set of plans for the colony whose constitution Simcoe described as the Magna Carta under which Upper Canadians would be "admitted to all the privileges Englishmen enjoy."

The position of lieutenant-governor of Upper Canada was created by the Constitutional Act which came into effect on June 19, 1791. Simcoe's commission as Lieutenant Governor was signed by the King on September 12th, 1791 but Simcoe was hard at work prior to this time. In a letter to an official in Upper Canada dated May 20, 1791 Simcoe gave him instructions regarding salt springs in the new province.

|

|

Elizabeth & John Simcoe |

Simcoe, his wife Elizabeth and their two youngest children, two-year old Sophia born in 1789 and three-month old Francis born in 1791, proceeded to Weymouth to depart for Canada. They left behind in the care of close friends their four eldest daughters: Eliza born in 1784; Charlotte in 1785; Henrietta Maria (known as Harriet) in 1787 and Caroline in 1788. A sixth daughter, Katharine, was born in Canada at Newark on the 16th of January, 1793. Their party was unable to depart on His Majesty's 21-gun frigate, Triton, because of unfavourable weather which kept them at Weymouth for nine days. The time was well spent. Simcoe had last minute consultations with Prime Minister Pitt and dined with Lord Grenville, the foreign secretary. They also met with the King and Queen on several occasions, the old king being quite taken with the petite, pretty wife of his new lieutenant governor. The sovereign gave Simcoe a letter to deliver to his son, Prince Edward, who was then serving with his regiment in the garrison at Quebec. He bade them bon voyage and urged them to take care of his interests "in that far off place."

At 1:00 p.m. on Monday, September 26th, 1791 the Triton with a fair wind and under a bright, sunny sky departed on its perilous voyage across the Atlantic Ocean. All sails were unfurled to take advantage of the favourable weather in order to reach Quebec before ice made the St. Lawrence dangerous for shipping. As the frigate labouring under a full load of canvas dipped headlong into the wave of the Channel, Elizabeth felt a little giddy and took to her cabin instead of sitting down to dinner with the others.

|

Because it was the season of storms and contrary winds, it was a nightmare trip for all aboard. It was a full week before Mrs. Simcoe made an entry in her diary and then she recorded that the "waves rising like mountains have the grandest, most terrific appearance and when the ship dashes with violence into the sea, I viewed this tempestuous scene with astonishment." Below decks everything was wet and dirty "besides being bruised by sudden motions of the ship and half drowned by leaks in the cabin." The never-ending noise of waves, straining timbers and ropes was such, she said, "to deprive one of one's senses." She kept her sense of humour, however, recording that all were "quite diverted" by mishaps at mealtime, when despite all precautions, cups, saucers, plates and platters were sent flying to every corner of the room.

|

The Triton, a frigate of 28-guns which meant it was small for its class, rolled badly on the gentlest of seas and tossing storms pounded the little vessel relentlessly. Whipping winds stripped some sails away from the ship and blew them many miles south of their course. Then the vessel was becalmed for five days. The closer they came to their destination the colder it got. In the Gulf of St. Lawrence the rigging froze and the sailors suffered terribly.

Simcoe recorded that the ship,

In His Own Words,"met with some very heavy Gales, particularly in the River St. Lawrence but the Triton weathered the blustery passage without the slightest damage because of the knowledge and foresight of Captain Murray."

They anchored safely at Quebec City on Friday, November 11th at one a.m. After forty-six days on the savage sea the city must have been a welcome if somewhat dreary sight for it was shrouded in mist and buffeted by a driving wind that sent sleet slashing through the bitterly cold air. The scene was so bleak and depressing Elizabeth was reluctant to leave the ship.

In the absence of Lord Dorchester, the Governor General of all British North America who was then on leave in London, it became the responsibilty of Major-General Sir Alured Clarke, Lieutenant-Governor of Lower Canada, to proclaim that the Constitutional Act would take effect on the 26th of December, 1791. Because of a technicality the newly-created province of Upper Canada was without a legally constituted government for six months. Simcoe had no civil powers until his commission had been read and the oaths of allegiance and of his office were administered in the presence of at least three members of the Executive Council. Since they had not yet arrived from London, Upper Canada had a lieutenant governor in name only so without a government Upper Canada was in legal and legislative limbo. A frustrated Simcoe lamented, "I impatiently await the Gentlemen of the Council."

|

In typical fashion Ssimcoe did not let this technicality interfere with his plans. On February 7th, 1792 he issued a proclamation written by his aide, Thomas Talbot, addressed, "To such as are desirous to settle on the Lands of the Crown in the Province of Ontario." By virtue of not yet having been sworn into office, Simcoe wondered whether the proclamation was even legal. It was, however, never challenged and served the settlement in Upper Canada until well into the 19th century.

The proclamation set forth the following features of the land-granting system.

(a)Townships were to be ten miles square in the interior or nine by twelve miles along navigable rivers.

(b)The size of a farm lot was fixed at 200 acres, but at Simcoe's discretion a grant could be increased to 1000 acres.

(c) Land petitioners had to swear an oath of loyalty to the King and give assurances they would clear and cultivate at least two acres of their land within a certain period.

(d)Grants were made only after surveyors had reserved one-seventh of the land in each township for support of the Protestant clergy and set aside an additional one-seventh "for the disposition of the Crown."

|

|

These 'Crown Reserves' were not mentioned in the Constitutional Act but were approved later by the British government in order to provide a source of revenue for the governor and so free him from dependence for finances on the good will of the Assembly.

While Simcoe was dedicated to keeping hated republicans from acquiring property in Upper Canada, he was anxious to welcome Americans who were even passively loyal to the King. In order to attract them he increased the size of land grants to 80 hectares and advertised widely in the United States for settlers. Simcoe stressed that Quakers, Mennonites and Tunkers, who "from certain scruples of conscience declined to bear arms," would not be required to do so in Canada as they had been forced to do during the American Revolution. Quakers, many of whom were of German origin, were excellent farmers and Upper Canadian agriculture was to benefit greatly from their presence.

The original Loyalists living in Upper Canada were outraged by what seemed to some to be a royal reception for rebels. Loyalists heard with astonishment that some of those granted townships in Upper Canada were the same individuals they had encountered on the field of battle fighting under the banners of rebellion or who had been otherwise notoriously active in promoting the American revolution. Despite criticism Simcoe persisted in welcoming American settlers. The colony needed colonists and he knew Americans were the best Upper Canada could get. Never intimidated by the toil that faced them, they displayed great dexterity in the use of the axe, hewing down the largest trees with skill and expedition as they quickly cleared and cultivated their land.

|

In addition to being anxious about his authority Simcoe was agitated about his military rank, a subject that preoccupied him throughout his career. On the day after arriving in Quebec he expressed concern about not having received a 'Letter of Service as a Colonel.' Simcoe badly wanted the rank of brigadier-general and when he failed to receive it he blamed it on the presence in Quebec of the King's son, the Duke of Kent. The Duke like Simcoe also held the rank of colonel and Simcoe mistakenly believed royal protocol prevented him from outranking the king's son. In fact the king for whatever reason simply did not wish to grant Simcoe that rank. Until Simcoe had a troop to command he had no military rank at all and this situation persisted until the newly raised regiment of Queen's Rangers began arriving in Canada. Named for his old fighting corps the new Queen's Rangers had converted their swords into ploughshares.

|

Their first function was not to fight but to fabricate. Simcoe described their role.

In His Own Words"They are to employ themselves in the civil purposes of the Colony in the construction of various public works, including Buildings, Roads, Bridges and Communications by Land and on the Waters and to undertake to perform their duties zealously and vigorously." Although they were not primarily intended to perform military duties, they were nonetheless to be disciplined "in the manner of fighting in which the Indians excel," and be able to demonstrate at any meeting with Native warriors that they were the "better marksmen."

Weary of waiting and restless to resume the trip to the seat of his government in Upper Canada, Simcoe chaffed at his delay in leaving Quebec City. He was anxious to set in motion the machinery of government and to throw himself heart and soul into the work of governing this brand, new province. He exclaimed that "a thousand details crowd upon my mind," and fully expected every officer in every department to be "animated by one spirit for the public good and lay the foundations for a country which if justly administered may remain for ages united and attached to the Parent State."

|

In the absence of the Gentlemen of the Council Simcoe had to cool his heels at Quebec far longer than he wished. On one occasion he cooled more than his heels. He and Mrs. Simcoe were walking across an ice bridge when he slipped and plunged headlong into the icy waters of that "most august of rivers," the St. Lawrence. Later a friend chided him about "making so free of the country" and hoped he "got no cold from so uncomfortable an operation."

|

The first two shiploads of troops arrived at Quebec on the 28th of May, 1792. They were followed on June 11th by the second division. As soon as the first Queen's Rangers arrived in Quebec, Simcoe donned the green uniform of colonel of the Rangers. On June 22nd he set off for Kingston where his troops were to rendezvous and from where all were to proceed as soon as possible to Niagara. Finally, Simcoe set out for his new province. As to the country itself, it was essentially woodland, native forest trees and uncultivated land, a primitive, almost primeval wilderness. There were settlements here and there occupied by the United Empire Loyalists who sought to cultivate the chaos by felling great trees and subjugating the soil.

Simcoe took his oaths of office at Kingston on Sunday, July 8th, 1792 before three Executive Councillors - Chief Justice William Osgoode, Peter Russell and James Baby. Two other Executive Council appointees, Aeneas Shaw and Alexander Grant, were sworn in a few days later. On July 16th writs of summons calling them to the Legislative Council were issued to the above-named five men, and to William Robertson, Robert Hamilton, Richard Cartwright, John Munro, Richard Duncan.

At the same time Simcoe appointed the following officials:

Major Littlehales, Military Secretary

Colonel Thomas Talbot, aide-de-camp

Robert Gray, Solicitor-General

John Small, Clerk of the Executive Council

William Jarvis, Civil Secretary

|

|

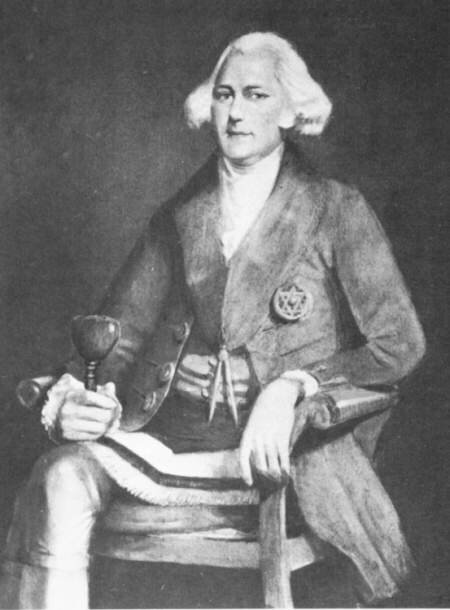

William Jarvis |

|

|

Jarvis as a Mason |

|

|

William Jarvis's Queen's Uniform (William Jarvis wore this uniform at dinners, balls and other social occasions. Today it is kept at Old Fort York in Toronto.) |

William Jarvis, whose father was the town clerk of Stamford, was born in Connecticut in 1756. William's twentieth birthday also marked an historic date: the year in which the Americans declared their indenpendence. William chose King over Congress and took up arms as a Loyalist to put down the revolutionaries. It was a fateful decision. He joined a fighting corps called the Queen's Rangers in 1777 whose the commander was Colonel John Graves Simcoe. In 1792 Simcoe was appointed first lieutenant-governor of Upper Canada, the colony that resulted from Loyalists like Jarvis. Simcoe loved the Loyalists, remembered his comrade in arms and appointed him civil secretary.

Why would a twenty-year-old ensign, a junior officer one of whose tasks was to carry the flag into action, attract the attention of the commanding officer to such an extent that he was given an appointment as a senior government official for a reward? In June of 1781 during a skirmish between the Queen's Rangers and some American revolutionaries on a road in Virginia between Williamsburg and Jamestown—the battle of Spencer's Ordinary or Spencer's Tavern, in case you're ever in the area—ten of Simcoe's Rangers were killed and twenty-three were wounded. The wounded included two junior officers, one of whom was William Jarvis.

John Graves Simcoe was raised in a military family. His father was a British naval officer. Simcoe felt a duty and a responsibility toward the men who were wounded under his command. In a book he published after the war, entitled A Journal of the Operations of The Queen's Rangers from the End of the Year 1777 to the Conclusion of the Late American War, he mentioned the two wounded junior officers, one of whom was Jarvis.

After the war Jarvis tried to return to a normal life in Connecticut, b Americans who had fought for independence were less than pleased to have Loyalists as neighbours and they faced great hostility. William Jarvis was injured in an anti-Loyalist incident and his family's property was confiscated. Most Loyalists ended up fleeing from the new republic, either north to what is now Canada or across the Atlantic to Britain. In 1784 or 1785 Jarvis moved to England.

Jarvis's life in England seems to have been much more comfortable and worry-free than that experienced by the average Loyalist. Generally Loyalists struggled in the post-war period because of financial difficulties, having lost everything in America: their homes, possessions, businesses and careers. As a result of their penury, they became obsessed with seeking compensation from the British government. However, such matters did not occupy Jarvis. He joined a local militia in England, found a wife (a good Loyalist girl from Connecticut, daughter of a clergyman) and started a family. Since no one named Jarvis was granted compensation by the British government in 1787, the most likely explanation for Jarvis's life of ease is that Simcoe was giving him assistance. The truth is that Jarvis rode to his small place in early Canadian history firmly on the coat-tails of the well-connected, upwardly mobile Simcoe, a more enterprising individual.

After the war in America, Simcoe set out advance his career. Money was of the moment and so he married an heiress. Shortly thereafter he was elected to the House of Commons, where, being a military man of few words, he failed to make much of an impression. He spoke on one occasion and his remarks drew a devastating reply from Edmund Burke, the formidable thinker and debater.

|

|

Edmund Burke |

Simcoe's most important work was to write A Journal of the Operations of The Queen's Rangers from the End of the Year 1777 to the Conclusion of the Late American War. Despite there being little interest in book about Britain's humiliating defeat, Simcoe had great stories to tell as one of the most successful British commanders during the war. He published it privately in 1787 and sent a copy to the King and later copies to various other prominent government officials. He fondest wish was an official appointment in North America and he made no secret of his desire to serve in that faroff place. With the copy of the his book to the under-secretary of state, he petitioned: "I should be happy to consecrate myself to the service of Great Britain in that country in preference to any situation of whatever emolument or dignity."

|

|

Simcoe was a humanitarian officer |

Government appointments were suspended while the British Parliament debated legislation to reorganize the remaining North American possessions on the Atlantic coast and up the St. Lawrence River. After a lengthy delay, Simcoe's efforts were eventually rewarded. The former province of Quebec was split into two provinces: Upper Canada (today's Ontario) and Lower Canada (today's Quebec). Before the Constitutional Act was officially passed in 1791, Simcoe learned that he would be appointed the first lieutenant-governor of Upper Canada. It was his recommendation that William Jarvis be appointed first secretary and registrar of the new province.

While the energetic Simcoe made plans for administering and developing Upper Canada, William Jarvis dreamt mostly of the money his new position would bring him. There was an annual salary of 300 pounds, as well as all the fees he would collect by issuing land titles. In a letter to his brother just before leaving England, William spelled out his hopes in some detail.

"I am told that, at this moment, there is not a single grant of land in U.C. but the lands are held by letters of occupation and that the grants are all to be made out by me after my arrival, at which the Secretary of L.C. (Lower Canada), is not well pleased, as the letters of occupation have been issued by him for some years without fee or reward, and by the division of the Province of Canada, all the emoluments fall to my portion; there is, at this moment, from 12 to 20,000 persons holding lands on letters of license in Upper Canada at a guinea only each is a pretty thing to begin with."

Within days of reaching Kingston, Upper Canada, Jarvis was complaining about his workload. "I have been very busy since my arrival here writing Proclamations," he wrote to his father-in-law. "It has been my ill luck to be obliged to copy so many in manuscript; the one at this moment in hand contains 11 sheets of foolscap. Tomorrow they go to Montreal for the press, yet I have had to prepare 8 copies in manuscript."

Simcoe had already reprimanded Jarvis for not being prepared to take on his new job. Jarvis had not brought sufficient supplies from Britain, items such as parchment and beeswax and especially a screw press so that documents could be imprinted with the Great Seal of the Province.

During the next year or two, Simcoe looked for the best location for the provincial government, first trying Niagara, then scouting the area of London and finally settling on Toronto. Jarvis always moved slowly and reluctantly behind Simcoe, complaining about the inconveniences and the loss of comfort to him and his family. His comments about the first move from Kingston to Niagara are typical.

"Col. Simcoe is at present very unwell at Niagara and if he has a good shake with the ague, I think it will be justice for his meanness in dragging us from this comfortable place (Kingston), to a spot on the globe that appears to me as if it had been deserted in consequence of a plague."

A few years later before Simcoe set off from Niagara to look over the Toronto site, Jarvis wrote sarcastically, "After the Assembly is prorogued, the Colonel and his suite are to go to Toronto a city-hunting. I hope they will be successful." When Simcoe decided that Toronto would be the seat of government, Jarvis complained that he didn't want to leave his comfortable home in Niagara. He delayed doing so until his colleagues lost patience with him.

William had a soul-mate in his wife. In a letter she wrote to her father from Niagara, she complained, " The Governor & famiy are gone to Toronto [now York] where it is said they winter and a part of the regiment. They have or had not four days since a hut to shelter them from the weather. They live in tents and warm themselves in bowers made of the limbs of trees. Thus fare the regiment. The Governor has two canvas houses. Everybody is sick at York, but no matter, the Lady likes the place therefore every one else must. Money is a God many worship

... |

|

Hannah Owen Peters was the daughter of Reverend Samuel Peters of Hebron, Connecticut. She married William Jarvis in 1785 in St. George's Church, Hanover Square, London. They had three sons and four daughters." |

When Jarvis was in England, preparing to sail for Upper Canada, he wrote the following to a relative in New Brunswick. "I am in possession of my sign manual from His Majesty constituting me Secretary and Registrar of the Province of Upper Canada, with the power of appointing my Deputies, and in every other respect a full warrant. I am also very much flattered to be able to inform you that the Grand Lodge of England have within these very few days appointed Prince Edward [the Duke of Kent, father of Queen Victoria - ed.], who is now in Canada, Grand Master of Ancient Masons in Lower Canada; and William Jarvis, Secretary and Registrar of Upper Canada, Grand Master of Ancient Masons in that Province. However trivial it may appear to you who are not a Mason, yet I assure you that it is one of the most honourable appointments that they could have conferred. The Duke of Athol is the Grand Master of Ancient Masons in England. Lord Dorchester with his private Secretary, and the Secretary of the Province, called on us yesterday and found us in the utmost confusion, with half a dozen porters in the house packing up. However his Lordship would come in, and sat down in a small room which was reserved from the general bustle . {Letter of March 28, 1792. From Henry Scadding's Toronto of Old, pp. 202-3]

.Jarvis had become a Mason one month before becoming "Grand Master of Ancient Masons in Upper Canada." After a few years in his august position, the Masons of Upper Canada tried to force Jarvis out of his position, accusing him of being lazy and incompetent. Jarvis was often referred to by contemporaries as "Mr. Secretary Jarvis," a title mocking his pretentiousness.

Peter Russell, Receiver GeneralDavid William Smith, Surveyor-General

Thomas Ridout and William Chewett, Assistants to the Surveyor-General

Peter Clark, Clerk of the Legislative Council [*]Colonel John Butler,Superintendent of Indian Butler's Rangers

The following picture of Butler's Rangers uniforms were taken in front of the regimental colours. Provided courtesy of Zig Misiak, they are from the late Lorne Butler, a direct descendant of John Butler. The uniforms are the only known authentically reproduced colours of uniforms worn by these famous Rangers.

|

|

Butler's Rangers |

When Simcoe began to govern officially on Monday, July 16th, he issued two proclamations. The first divided the province for electoral purposes into 19 counties extending from Glengarry on the east to Essex on the west. Simcoe based the names of a number of the new counties after his superiors or friends in England. Dundas County was named after Lord Henry Dundas Secretary of State for Home Affairs and War. Grenville Township was named for Lord William Grenville, the author of the Constitutional Act. Stormont County was named after Lord Stormont, who although he opposed the Constitutional Act, had so impressed Simcoe with his speech during the debate in the House of Lords that Simcoe decided "to celebrate Stormont's name." The name Pelham honours Charles A. Pelham, a close personal friend of Simcoe and Member of Parliament in 1792.

|

|

Lord Willam Grenville |

Simcoe chose many names from places in England, particulary from the shires of eastern England where several generations of Simcoe's forebears had lived. These included names from Lincolnshire County among which were: Lincoln, Grimsby, Crowland, Willoughby, Wainfleet, Louth, Saltfleet, Humberstone, Grantham, Newark, Caistor and Stamford. Simcoe allocated the sixteen representatives in the Legislative Assembly based on the existing settlements in the province as gauged by the militia returns which listed all men fit to fight in the colony between the ages of 16 and 50.

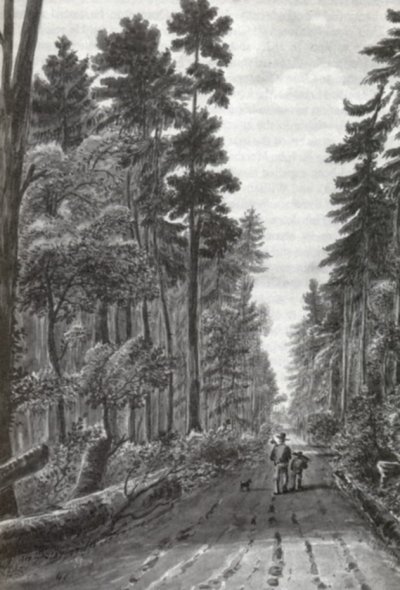

A second proclamation directed that elections be held in sixteen electoral districts (ridings). Writs for these elections were issued on July 26th, 1792 to be returned on the 12th of September. In addition nine men were summoned to serve on the Legislative Council. Simcoe's proclamations were speedily conveyed around the province and notices were posted in every settlement. In 1792 throughout the province in August and early September, the thinly scattered pioneer voters wearily made their way to the polls. Many impediments were encountered along the way, for travel through the trackless forests and over stump- and rut-filled muddy roads was difficult and slow going. [*]

|

|

Road between York and Kingston |

In the fall farmers were torn between getting out to vote and harvesting the crops that ensured their families' survival during the coming winter.

|

In Upper Canada during the late 18th century, elections lasted six to eight days and lacked today's formalities. There were no voters' lists and no secret ballot. Electors in each county simply assembled on the given dates in the designated locations where candidates were nominated, speeches made and by a show of hands were elected to Upper Canada's very first Legislative Assembly. The province's proud electors chose the following friends and neighbours to represent them in the province's first parliament. From far-off homes by foot with backpack, on horseback with saddlebags full of food for man and horse and in birch-bark canoes skirting the margin of Lake Ontario, they travelled to York take up the task of governing this new land.

|

The following men were elected to Upper Canada's first Legislative Assembly.

(2) Glengarry (brothers) 1st Riding - Hugh Mcdonell; 2nd Riding - John Mcdonell who became Speaker of the first Legislative Assembly; both were United Empire Loyalists, [U.E.] and maternal uncles of Lieutenant-Colonel John Macdonell, Brock's aide-de-camp, whose body lies alongside Brock's at Queenston Heights.

(1) Stormont - Lieutenant Jeremiah French, U.E., from Vermont.

(1)Dundas - Alexander Campbell of whom little is known.

(1) Grenville - Ephraim Jones, U.E., afterwards judge of the King's Queen's Bench;

(1) Leeds and Frontenac - John White, English barrister, appointed Attorney-General of Upper Canada; White, who was elected as a result of Simcoe's influence, died fighting a duel.

(1) Addington and Ontario - Joshua Booth, U.E., died in War of 1812.

(1) Lenox [Lennox] Hastings and Northumberland - Lieutenant Hazelton Spencer, U.E.

|

|

Lord Hastings Moira Rawdon |

(1) Prince Edward and Adolphustown: [Adolphustown was detached from Lenox for electoral purposes],

Philip Dorland was elected first, but being a Quaker he declined to take the oath of allegiance to King George III. In those days, conscientious objectors received no special consideration, consequently he was not considered "a fit and proper person." A new writ had to be issued for "one good knight girt with sword" [the old English terminology and it was imported to Canada.] Major Peter Van Alstine was elected and took his seat in 1793. Both Dorland and Van Alstine were U.E.

|

(1) Durham, York and 1st Lincoln - Nathaniel Pettit U.E. of Grimsby, an officer and member of Land Board of Nassau District.

(1) 2nd Lincoln - Colonel Benjamin Pawling U.E. an officer and member of Butler's Rangers in the Revolutionary War. He defeated Samuel Street, a merchant, by 148 to 48 votes.

(1) 3rd Lincoln - Isaac Swayze U.E., an officer and noted British scout whose enemies called him a spy, a mere difference in terminology.

(1) 4th Lincoln and Norfolk - Parshall Terry U.E. an officer who afterwards drowned in the Don River.

(1) Essex and its adjoining county, Suffolk [now Elgin] - David William Smith, son of Major John Smith, commandant of Fort Niagara. David William Smith, deputy surveyor-general and deputy judge advocate at Newark, indicated on July 26th, 1792, that Suffolk had no inhabitants. He also stated that only "those who have certificates [land grants] can vote." In a letter dated August 6th, Smith refers to the upcoming elections in which he expects the hustings [where the vote and election speeches for that county took place] for Essex [like most of these counties, Essex was much larger then than it is now] would be situated "somewhere about the river's mouth."> [River La Tranche - Thames River] Smith told his campaign manager that this would be a good place for "an ox to be roasted whole on the common and a barrel of rum be given to the mob to wash down the beef," in exchange for which the 'mob' would be expected to vote for Smith. He promised to cover all expenses.

|

Smith revealled that to ensure his election, the Governor had "prevented others" from running against him. He hoped that "the sentiments of the people (the preference of the voters) will be known before the poll" on August 27th. Although he ran unopposed Smith spent more than 233 pounds in 'treating' the electors, whom he always referred to as 'peasants.' In some of his correspondence Smith referred mistakenly to the House of Assembly as the "house of representatives," an embarrassing slip of the lip surely, and one which Simcoe would have angrily corrected, since this was the American name for its legislative body.Because elections took place over several days it was possible, theoretically, for a candidate to lose in one county only to mount a new campaign and be elected several days later in another riding. It was thought David William Smith may have taken advantage of this opportunity, running first in Kent County where he was defeated, then running in Essex-Suffolk where he was elected unopposed.

(2) Kent - William Macomb and Francis Baby, the latter of French Canadian descent.The House of Assembly was described as a "lair of warriors" with good reason, for many of its members were former military men. John Mcdonell, the Speaker, had been a captain in Butler's Rangers, a corps with an uncommonly notorious reputation in the United States. Hugh Mcdonell held the rank of lieutenant in the King's Royal Regiment of Foot in which Jeremiah French and Hazelton Spencer also served. Benjamin Pawling had been a captain and Parshall Terry a lieutenant in Butler's Rangers. Isaac Swayze was a scout, a spy and a naval pilot for the British army while it was stationed in New York. D.W.Smith was a lieutenant in the 5th of Foot regiment garrisoned at Niagara.

In accordance with the Constitutional Act, the lieutenant-governor with the advice and consent of the elected Assembly, was charged with making laws for the peace, order and good government of the people under his jurisdiction. The governor was aided in this endeavour by three other bodies, which together comprised the government of Simcoe's "dream province." Their combined functions were to administer, to advise and to legislate.

The Legislature comprised the appointed Legislative Council and the elected Legislative Assembly. A third body, the appointed Executive Council, acted as a kind of cabinet, its members being close advisors of the governor. The two appointed bodies were controlled largely by a group of individuals who became known as the Family Compact, a tiny fraction of the population which wielded tremendous power. Believing human nature to be essentially evil, the Compact felt that if the poorly educated, ill-informed majority were given power, chaos would result as had happened in the United States. The elected members of the Assembly and by extension all those they represented, were relegated to a lesser role in government and this created tensions which were worsened by the Compact's refusal to compromise on any issue of real importance and its tendency to treat critics in a the petty, vindictive way. The degree of resentment from the general public regarding this privileged group varied depending on whether one were conservative or liberal in outlook. Liberals or reformers grew increasingly frustrated by and critical of the few who controlled everything, and eventually under militant leaders some of them decided to take matters into their own, armed hands.

[*] Jokes about the pathetic condition of the roads were widespread. A man was walking down the street of a small town and saw a hat in the middle of the road. He stooped, picked it up and was amazed to see beneath it the head of a man sticking up from the mud. When he expressed concern the man said, "Don't bother about me, it's the horse I'm riding that needs help."Copyright © 2013 Website Administrator