foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

THE ORIGIN OF THE FAMILY COMPACT:

UPPER CANADA'S ARISTOCRACY

History is a gallery of personalities.

"What was the nature and origin of the Family Compact, this powerful organization, this informally-constituted league. Its members were for the most part appointed on the recommendation of various supporters of the Government of the day who were able to provide for a number of their needy relatives and dependants. This was a matter of vastly greater importance in their eyes than the proper administration of the affairs of a distant and newly-acquired colony. The appointment was a boon to many servile hangers-on of public men in Britain and scores of waifs and strays of British aristocracy who began to turn their eyes to Canada as a cold, comfortless but possibly last resource of emergency."

The framers of the Constitutional Act intended the Legislative Council and the Executive Council to operate independently of each other. The latter body, while not specifically mentioned in the Act, was referred to indirectly in Section 38. While not a part of Upper Canada's parliament the Executive Council represented a kind of cabinet whose function was to assist the lieutenant governor to administer the province. As it turned out the Executive Council played a large and considerably more controversial role in the government of the province than anyone ever expected.

|

|

|

Executive Council members were "to have and enjoy Freedom of Debate and Vote in all Affairs of Public Concern." Meeting approximately once a month its members considered petitions for land and other special favours, issued regulations and approved grants and licences as recommended by government officials. The Executive Council also constituted a court of civil jurisdiction for hearing and determining appeals from any of the courts of common law in the colony.

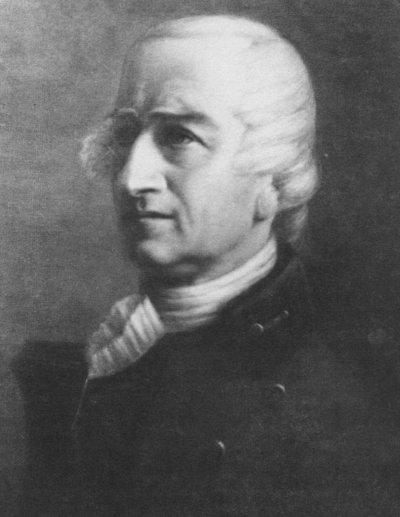

In a lengthy letter to Lord Dorchester, governor general of Upper and Lower Canada, the Hon. W.W. Grenville, Secretary of State and creator of the Constitutional Act of 1791 sought Dorchester's recommendations regarding appointments to the Executive and Legislative Councils.

In His Own Words"It is intended to separate the Legislative and Executive Councils and to give to the Members of the former the right to hold their seats during their lives and good behaviour."

|

|

Lord Dorchester |

Notwithstanding the fact that the Legislative and the Executive Councils were two separate bodies, Grenville explained that members of the Legislative Council could also be members of the Executive Council. He cautioned Dorchester that great attention should be paid to the choice of these important people. Dorchester turned for recommendations to Sir John Johnson, the Superintendent of Indian Affairs, following which Dorchester submitted eight names for possible appointment to the Legislative Council: William Drummer Powell, Richard Duncan, William Robertson, Robert Hamilton, Richard Cartwright, Jr., John Munro, Nathaniel Petit and George Farley.

Thirteen names were forwarded for consideration for membership on the Executive Council: William Drummer Powell, Richard Duncan, William Robertson, Richard Cartwright, Jr., James Gray, Alexander McKee, Edward Jessup, Alexander Grant, John Mcdonnel, James Mcdonnel, Peter Drummond and Robert Kerr.

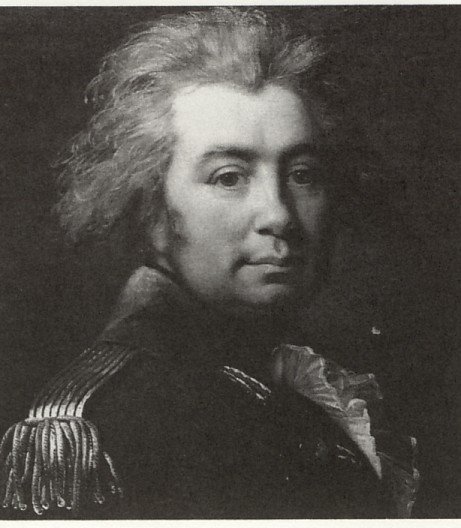

John Graves Simcoe brought vision, vigour and vitality to the task of developing his 'dream province' of Upper Canada.

|

|

John Graves Simcoe |

Who were the select few who shared power with him and became comparable in Upper Canada to Britain's aristocracy? On September 19th, 1791 Simcoe was informed that his Executive Council would be limited to the following five members: William Osgoode, William Robertson, Alexander Grant, Peter Russell and a French Canadian in Upper Canada subsequently selected named James Baby. The members of the Legislative Council were William Osgoode, Richard Duncan, William Robertson, Robert Hamilton, Richard Cartwright, Alexander Grant, Peter Russell and John Munro. Robertson never returned to Canada from England and did not serve on either council. While it was not intended that the same individuals would necessarily serve on both councils, all members of Simcoe's Executive Council did eventually serve also as members of the Legislative Council.

This overlapping of leaders was not seen to be a problem early in the life of the Legislative Assembly, but it became a cause for concern later as indicated in this address to the King from the Legislative Assembly dated April 19th, 1836. "For many years, the Legislative Council of Upper Canada consisted of but four or five members connected with the Executive government by the most confidential relations and forming in reality a body scarcely distinct from the Executive Council of the colony." Simcoe was unable to do much about the fact that the elected Legislative Assembly was destined to be dominated by men with "levelling tendencies," an expression meaning those having democratic ideas about all persons being equal. He was determined that a staunchly Tory clique would control the councils.

Both councils became comparable to exclusive clubs whose members were largely British-born men who together with the governor formed a tiny oligarchy which held all real political power in the province. Simcoe was dedicated to conferring authority and special privileges on this untitled but very powerful group of British elite which eventually became known as the Family Compact. It comprised leading members of the administration, members of the executive council, senior officials and certain members of the judiciary. They were bound to each other and to the British connection by four golden chains: titles, pensions, sinecure posts and highly paid jobs. By controlling the day-to-day operation of the machinery of government they controlled the colony.

The Family Compact existed, according to the Reverend Mr. Smart who came to Canada in 1811 and was called upon to preach the funeral sermon of Canada's great hero, General Brock, because it was necessary for the Government in Council to make laws and govern the people "in as much as the vast majority of the inhabitants were like most of the United Empire Loyalists, unlettered and unfit to occupy places which required judgement and discrimination." Having enjoyed exclusive power the Council became unwilling to share it with the representatives of the people. By the time the masses had acquired some idea of Responsible Government and were unwilling any longer to be kept in obscurity, the resultant tensions led to war between the Tory and the Radical.

One of the most influential of this elite group was William Osgoode, Chief Justice of Upper Canada and later Lower Canada. Osgoode, who became the senior member of both Councils,was born in London in 1754 to William Osgoode, a hosier. There is no evidence to support the family claim that Osgoode was a natural son of George II or an intimate friend of William Pitt. He was called to the English bar in 1779 but because he was afflicted with a speech hesitation he did not practise law as a barrister. He was appointed chief justice of Upper Canada in 1791. In spite of his modest beginnings. Osgoode developed an arrogant attitude toward colonials and assumed aristocratic pretensions when he came to Canada. He became a close friend of Simcoe's, and was a key Tory in Upper Canada where he exercised a powerful political influence. His good looks, good manners and kindliness made him popular. He was never as fully committed to the province as Simcoe but was a more rigid Tory. He could not abide Americans and considered New York "the very hotbed of Turbulence and Disaffection." In addition to being chief justice Osgoode was chairman of the Executive Council and Speaker of the Legislative Council. He was the only member of both councils to attend all sessions held over a two-year period. As chief justice he was the highest paid provincial official receiving 1000 pounds annually, half Simcoe's salary. Osgoode was a close colleague of Simcoe's and his direct representative in the Legislative Council where he vigorously defended Simcoe against any opposition.

|

|

William Osgoode |

When Osgoode who was appointed chief justice of Lower Canada in 1794 Simcoe said he found his absence "most severely oppressive." In Lower Canada Osgoode never enjoyed the same support and confidence that was given him by Simcoe. He was not the charming, hard-working individual there that he had been in Upper Canada. In fact, Osgoode was accused by Lower Canada's Lieutenant Governor Prescott of being vain and idle and conniving to acquire large tracts of land totalling 12,000 for himself. When relations between the two men became strained, Prescott was warned by London that reconciliation was necessary but when this became impossible Prescott was recalled to England. During his time in Lower Canada Osgoode made so many enemies it was said the only living things he liked were his horses which he described "as the best little Creatures in the Universe." In 1801 Osgood retired on a pension of 800 pounds to England where he lived fashionably in London in apartments formerly occupied by the Duke of York. He died in 1824. In Toronto his name is commemorated in Osgoode Hall, headquarters of the Law Society of Upper Canada.

On February 28th, 1796 Simcoe instructed all government officials to relocate their offices from Newark to the province's new capital, York. The order, made necessary by the anticipated American takeover of Fort Niagara when the British garrison moved out in the summer of 1796, was an unpopular one. Many officials had at considerable expense just established themselves at Newark and deeply resented being uprooted to live in York so soon at great a cost and inconvenience. The new capital that was little more than a clearing in the forest wilderness with all the risks this involved for man and beast. In 1800 when York's population was 336 one citizen recorded that during the night"a great depredation was committed by a flock of wolves that came into Town killing seventeen sheep." Later that year it was reported that "two great bears took away two pigs, picking them up in their arms and running away on their hind legs." One critic of the move angrily complained that the "civil Officers of Upper Canada were selected to be the sport of fortune." Some who were strongly opposed to making the move delayed the inevitable as long as they could.

Those who relocated immediately found housing scarce and construction costs high. The Provincial Secretary William Jarvis said he was "ten days in search of a hut to place his wife and lambs " but finally found a log hut with three rooms for which he paid 40 pounds. Jarvis was pleased that he had a roof over his head and a plentiful supply of winter food which included:"16 fine turkeys, a dozen ducks, 40 head of good cabbage, excellent turnips, pigs, a cow and some of the finest maple sugar I ever beheld." The sugar was acquired from an Aboriginal village near Michilimackinac. Hannah Jarvis, William's wife, was a sharp-tongued commentator on the local scene. She noted that with the Governor at York, the chief justice, attorney general, receiver general and secretary at Newark and the acting surveyor general, David William Smith, at Fort Niagara,"our government is to spend the Winter at respectable distances."

|

|

Hannah and William Jarvis |

An Irishman, Peter Russell, a tireless Simcoe supporter, was on Simcoe's recommendation appointed to seats on both the Legislative and the Executive Councils. Russell also served as collector of customs, auditor & receiver general of all government rents, lands & profits, justice of the Court of Common Pleas and justice of the King's Bench. Despite having spent a great deal of money for a comfortable home in Newark and incurring more expense to relocate to York Russell said he was only too ready to obey Simcoe's orders which he promised to do just as soon as circumstances made it possible. He apologized profusely for being unable to go immediately explaining to Simcoe that while he was "educated in the School of Obedience and accustomed to complying implicitly with the orders of my superiors," circumstances prevented him from immediately obeying on this occasion. He said he had paid 100 guineas for a small house at York but could find "no artificers" to add to it "on reasonable terms." The shortage of labour meant construction was expensive. Following Simcoe's return to England in 1796 Russell replaced him as administrator of the province and hastened to relocate to York in order "to accelerate the prosperity" of the new capital.

|

|

Peter Russell |

While as administrator Russell spent a good deal of time settling York by improving roads and speeding up work on public buildings he was somewhat handicapped by his lack of information regarding plans for the town. Simcoe had taken with him much of his correspondence including most of the official documents and directions he had received from his superiors in London. This left Russell in the lurch for he was completely ignorant of the plans British authorities had for the colony. Nevertheless, Russell faithfully followed the directions begun by Simcoe. During his tenure as administrator Russell was criticized by his colleagues for his greediness in accumulating fees and offices for himself and assigning grants of Crown land to himself and his sister. Residents made fun of the fact that land conveyances and grants specified, I, Peter Russell, convey to you, Peter Russell…." As an executive councillor Russell received 6000 acres of land and he had acquired thousands more by the time he died.

|

|

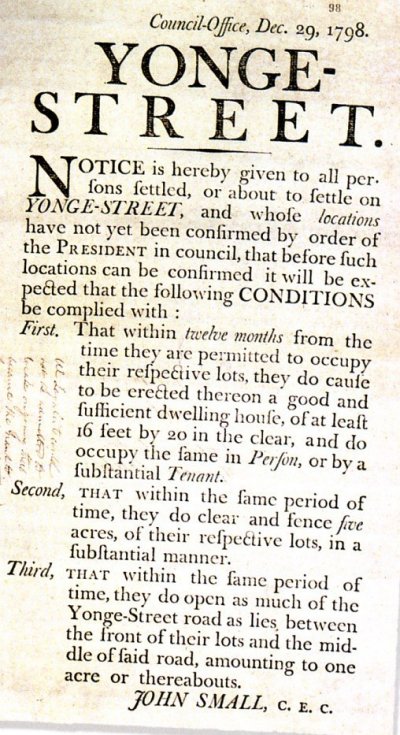

Yonge Street Strict Development Guidelines |

Russell was not distinguished for his intelligence or for his achievements and his leadership was cautious and uninspiring. He did correct a number of land abuses, particularly in York and its environs, where it was feared land would be used for speculative purposes. Russell directed that no town lot be issued without his express approval and he personally interviewed all land applicants to ensure they were serious about settling on the property. At the time York was a compact parallelogram bounded on the west by George Street, on the east by Ontario Street, on the north by Duchess Street and on the south by Palace now known as Front Street. Palace Street was so named because the Parliament buildings were to be constructed there, the only palace York was to have for some time to come. Russell also made the machinery of government work more smoothly. It was under his administration that York was really established as the colony's capital. Russell always hoped that he would be appointed lieutenant governor of Upper Canada but never was and died a disappointed person in York in 1808.

|

|

Upper Canada's 1st Parliament Buildings |

¨

James Baby, a French-Canadian, was appointed to both the Legislative and Executive Councils. Baby came from of a prestigious French family in the Detroit area which was recognized for loyalty to the Crown after the conquest. Baby's primary role was to secure the loyalty of the French colonists in the Detroit-Windsor area. After 1791 he became one of the Upper Canada's foremost office holders occupying between 1792 and 1830 more than 115 commissions and appointments including that of lieutenant of Kent County. In 1816 Baby was appointed inspector-general of public accounts (minister of finance), a post he held until his death in 1833. He performed his administrative and political duties faithfully and missed very few meetings of the Executive Council. Gracious and distinguished Baby was an impressive figure - tall, clean-shaven, good-looking and well-proportioned. According to his grandson Baby possessed "a primitive simplicity and moral beauty." He was described as "a Christian without guile," affable and polished in manners and dignified in deportment. He was one of the most influential members of the Family Compact and when he died in Windsor all its shops and offices closed for his funeral.

When Simcoe approved the appointment of Commodore' Alexander Grant for membership on the Executive Council he believed his membership would cause the Council

In His Own Words"at once to be stamped with the eminence and respectability of his professional situation and permit the Government to avail themselves of his experience.",

|

|

|

Grant, who was later appointed to the Legislative Council, served in the British navy throughout the Seven Years' War following which he was named naval superintendent for the Great Lakes with his headquarters located initially at a dockyard on Navy Island in the Niagara River and later at Detroit. Although distance and his official duties kept Grant from attending many meetings of the councils he remained an influential member.

The premature death of Lieutenant-Governor Peter Hunter in 1805 resulted in Commodore Grant being appointed chief administrator of the province. Initially he was insecure and uncomfortable in this new position of responsibility and rubber-s tamped all but one of Hunter's policies and practices. Grant explained it this way.

In His Own Words"Tho my late good, worthy predecessor was Sensible and Clever he latterly dealt very harsh with most of the people who had any business with him."

Grant was more conciliatory and his pleasant, easy-going manner was mirrored for a time by York's society allowing him to record that "All seems to be satisfied with matters going on quietly." When the new legislative session resumed things changed causing Grant to complain In His Own Words

"The House of Commons do's nothing but vomiting grievances and complaints against the administration of General Hunter and plaguing me and his favourites."

This description survives of Grant who was semi-literate and totally without pretence. He was "an old Scotsman, a large stout man not very polished but very good-tempered with a round, plump, pocked-marked face as red as a pomegranate." On being introduced to Prince Edward Augustus Grant is supposed to have exclaimed,"How do you do, Mester Prince? How does your Pawpa do?"

John Munro was a Scotsman who served during the Seven Years' War. As a disbanded soldier he received land in New York where he prospered as a merchant-trader and acquired over eleven thousand acres. During the American Revolution he served in the King's Royal Regiment and because of his Loyalist leanings lost at war's end an estimated 11,000 pounds. He sought without success full compensation from the British government. When he retired as a half-pay officer Munro received only 300 pounds and settled in the Eastern district a disillusioned man. He was subsequently compensated with large grants of land, one of which "was with the benefit of a stream running through it" on which he operated a saw mill which Simcoe visited and observed in operation. Munro received as well, various appointments including membership on the first Legislative Council. Although he served conscientiously as a legislator and a judge, Munro's public career was more notable for his unswerving loyalty to those in authority than for his independence of thought. He acquired land and wealth in Upper Canada but never regained the affluence he had in America before the revolution.

|

|

|

Richard Duncan was an Englishman who served in the Seven Years' War. During the American Revolution he became an ardent Loyalist and was rewarded by being named one of the nine original members of the Legislative Council as well as Lieutenant of Dundas County. Duncan's participation in the work of the Council was negligible, his contribution limited to the minor matter of establishing the Eastern District boundaries. He was more preoccupied with his father's property and trading business in New York where he spent a good deal of time. He was eventually removed from Council for non-attendance and died at his father's former home, The Hermitage located near Schenectady New York.

|

|

|

Aeneas Shaw was a Scot who served under Simcoe in the Queen's Rangers during the Revolutionary War. He eagerly accepted a commission as a captain in Simcoe's revived Queen's Rangers in Upper Canada and travelled on snowshoes from New Brunswick some 2400 miles in 19 days to take up his duties./p>

|

|

|

Simcoe described him

In His Own Words"as a man of Education, Ability and Loyalty, one of those Gentlemen most likely to effect a permanent Landed Establishment in this Country. He has a perfect knowledge of Infant Settlements, having with his own hands worked hard for some years to form one in Nova Scotia. He has strong claims upon the Government."

Major Shaw commanded one of the regiments that cleared the site atf York and he was among the first officials to move his residence from Newark to the new capital. During the initial summer there he and his family lived in a tent which blew over during a fierce storm in November, 1793 leaving his wife and seven children "exposed to the rude elements of wind and rain." He requested and received 400 acres of land in the township and town of York and was granted government materials to build a house"such materials to be replaced upon reasonable notice." Shaw was a member of both the Legislative and Executive Councils, Lieutenant of York County and one of its several magistrates. He and Peter Russell were the only members under Simcoe to attend regularly the meetings of the Executive Council.

When Peter Russell became administrator of the province he considered Shaw to be indispensable as a councillor. Among other duties Russell requested Shaw's assistance in laying out the town of York. Russel said Shaw also helped by "chusing a scite for the jail in a high and dry location for health and defence, by locating a church on a heighth" and by allotting land in the middle of town for a market place. During the war of 1812 Shaw was promoted to the rank of major-general and given responsibility for the training of the province's militia whose numbers totalled one tenth of colony's population. Shaw also led the unsuccessful defence of York in 1813. On retirement his rank entitled him to 6000 acres of land most of which remained unproductive during his lifetime. When Shaw died at York, each of his ten children received 1200 acres. One of Shaw's daughters, Susan, was rumoured to have been Isaac Brock's beloved and legend has it that she handed Brock a stirrup cup of coffee before he galloped to glory and into history at the Heights of Queenston on October 13, 1812.

|

|

|

According to Simcoe these "men of good Life, well affected to Our government and of Ability suited to their Employments" comprised the elite of the province. They acquired numerous offices and commissions during Simcoe's tenure and formed the core of the self-sustaining oligarchy. Successful Loyalists and merchants were also members of this clique but its leaders, the highest office-holders, were men born in Great Britain. Despite his high regard for Loyalists Simcoe was reluctant to trust high offices to Loyalist colonials because he feared their possible contamination with republican principles and a levelling outlook.

Simcoe was dedicated to the concept of an hierarchical, aristocratic society in the frontier wilderness and he was determined to form a permanent Landed Establishment in Upper Canada. In as many ways as he could Simcoe proceeded to endow with land and public offices the "well-affected and respectable classes" of the province. Large tracts of property were granted to certain prominent individuals with a view to making them proprietors of landed estates who would serve as local gentry. Simcoe was determined to use any opportunity to ensure additional prominence and prestige for his colonial aristocracy. Under the first Militia Act passed in 1793 he provided for the appointment of county lieutenants who in turn were responsible for the appointment of militia officers and the organization and training to the militia twice a year. Whenever possible Simcoe chose these lieutenants from among the members of the legislative council to increase their prestige and authority as the nucleus of Simcoe's colonial elite.

|

|

|

The governor's friends on the councils and their hangers-on comprised the select few who came to be known as the Family Compact. Its members, who did not come to Upper Canada with the Loyalists in 1783, came after 1791 from Britain, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. As time passed bitter resentment became focussed on the affluence and influence exercised by this small select group of un-elected individuals closely connected by religion, patronage, conservative conviction and in some cases marriage.

Frustration over their control of the government was articulated by Egerton Ryerson.

In His Own Words"The Lieutenant-Governor was assisted - mostly ruled - by an Executive Council consisting for the most part of salaried officers, judges and members of the Legislative Council who were responsible neither to the Governor nor to the Legislative Council nor to the House of Assembly. The Executive Council was an independent, irresponsible body - an oligarchy which exercised great power, was very intolerant and became very odious."

"As the years passed the Province became the resort of numerous office-seekers from beyond the sea - half-pay officers and scions of aristocratic Britains who sought to better their fortunes by expatriation. They acquired a strength and influence which in the then primitive state of the colony carried all before them. They wormed their way into important offices, directed the Councils of the Sovereign's representative and in a word became the power behind the Throne. They practically absorbed the Executive and Legislative Councils as these bodies were entirely made up of persons either selected from among them or entirely subservient to their influence. No man whatever his abilities could hope to succeed in any profession or calling in Upper Canada if he dared declare himself in opposition to them. A few made the attempt and failed most signally. Only in Upper Canada of all the British colonies did they attain such a plenitude of power as in this province and in none did it wield the sceptre of authority with so thorough an indifference to the principles of right and wrong."

Canada welcomed with open arms land-hungry Americans and poor, brow-beaten emigrants from Britain and Europe. While most of these newcomers were coping with nature and struggling simply to survive they were largely indifferent to the semblance of self-government in effect and were prepared to tolerate the preference and privilege it involved. As time passed and men and women began to consider their society more closely, they became critical of the folly and favouritism they saw about them. Friction resulted as tensions developed between the elected Assembly and the people it represented and the governor and his advisors who controlled all the power and enjoyed all its privileges. The extreme frustration felt by a few resulted in rebellion in 1837.

Copyright © 2013 Website Administrator