foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

5TH REGIMENT OF FOOT

History is difficult to surpass for adventurous incidents.

|

|

Flag of the British Army |

In its formative years Canada was well served by the British army, three important branches of which were the infantry, the cavalry and the artillery.

InfantryThe infantry comprised 19 regiments, the average strength of each being 477 personnel. Each regiment consisted of one battalion containing ten companies. Each regimental company was organized as follows: one Captain, two Lieutenants, 2 Sergeants, 3 Corporals, 1 Drummer and 38 Privates.

Of the 10 companies in each regiment one consisted of grenadiers and one of light infantry. When introduced into the army in 1667, the function of the grenadiers was to hurl hand-grenades among the enemy's ranks at close quarters. The size and weight of these missiles demanded that the throwers be tall of stature and muscular of build. By 1775 the grenades had disappeared, but the grenadiers remained and represented in height and strength the best of each regiment. The light infantry was introduced to provide each regiment with a corps of skirmishers who were good marksmen with a light build and active temperament. Grenadiers and light infantry came to constitute the picked men of a regiment.

One company of grenadiers comprised 1 Captain, 2 Lieutenants, 2 Sergeants, 3 Corporals, 1 Drummer, 2 Fifers; and 38 Privates. One company of Light Infantry comprised 1 Captain, 2 Lieutenants, 2 Sergeants, 3 Corporals, 1 Drummer, and 38 Privates.During an engagement these two specialized companies were usually placed in the flanks and hence were known as the "flank companies." In an army it was customary to combine all of these companies into one or two special battalions in order to make their united strength available for work requiring the highest courage and skill. At the Battle of Bunker Hill, the grenadiers flanked the British line on the left and the light companies on the right.

CavalryThe makeup of cavalry regiments was less uniform, but the majority numbered 231 sabres organized into 6 troops. Each cavalry troop comprised: 1 Captain, 1 Lieutenant, 1 Cornet (trumpet player), 1 Quarter Master, 1 Sergeant, 2 Corporals, 1 Hautbois (oboe player), and 37 Privates.

Military music to stir the heart and quicken the step of the British redcoat was of a simple sort. Each regiment had a few fifers and drummers. Each regiment of horse had a few trumpeters. Each regiment of Guards enjoyed in addition a band of 8 pieces: two oboes; two clarinets; two horns; two bassoons. The musicians were in many cases civilians hired by the month.

At very critical times in our early history a handful of red-coated regulars formed the foundation of the country's defences and did the lion's share of the fighting and dying. Their heroic accomplishments were all the more incredible considering that enlisting in the army was often the last resort of ne'er-do-wells and petty criminals seeking solely to escape from the law. The roll-call of regiments that served Canada is impressive, and among its number was the famous Fighting Fifth, whose badge bore St. George slaying the Dragon.

|

|

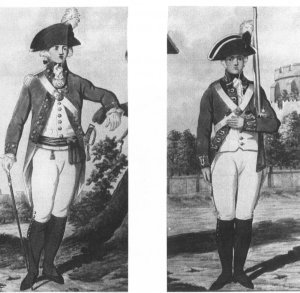

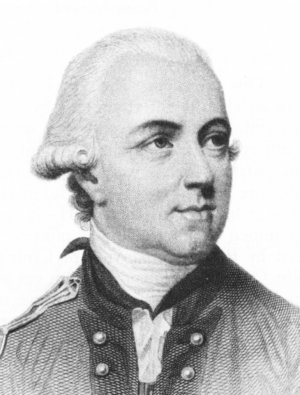

Officer (left) & Private of 5th Regiment of Foot |

To All Intrepid Able-Bodied Heroes Who are willing to serve His MAJESTY KING GEORGE the Third, in Defence of their Country, Laws and Constitution, against the arbitrary Usurpations of a tyrannical Congress have now not only an Opportunity of manifesting their Spirit, by assisting in reducing to Obedience their too-long deluded Countrymen, but also of acquiring the polite Accomplishments of a Soldier, by serving only two Years, or during the present Rebellion in America.

This regiment saw service during the Revolutionary War when its ranks were decimated during a fatal frontal attack on a hill. The Americans had taken possession of both the 110-foot Bunker Hill and the 75-foot-high Breed's Hill. Both hills overlooked the town of Boston which was occupied by the British. In order to prevent American shelling of the town and make the British position untenable, the heights had to be taken. History calls it the Battle of Bunker Hill but it was, in fact, fought on Breed's Hill as all Boston looked on from the surrounding ridges and rooftops.

Loaded with scarlet-coated men, twenty-eight barges arrived for battle all rowed precisely in line to the end of the peninsula. Off-loaded from each ship were brass field pieces glistening in the noon-day sun with a thousand points of light. The scene was a panorama, a brilliant blaze of colour. All the while the fleet's cannons belched flame and smoke in thunderous roar, the shells pounding harmlessly into the hillside because the guns could not be angled high enoug to hit the men entrenched at the top.

|

With raving fifes and rattling drums the soldiers landed in their red coats and immaculate white breeches, the brilliant rays of the sun dancing on the tips of their bayonets as they formed into three lines. News of the red coats' arrival resulted in bells being rung, drums beaten and anxious American officers running about calling out to their men to do they knew not what.

|

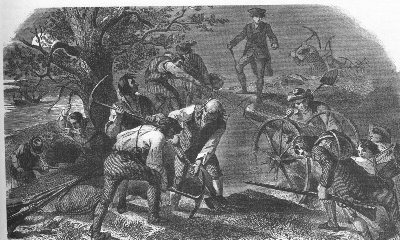

The Colonials had been busy, however, for dawn on June 17th, 1775 revealled that during the darkness as if by magic the Americans had constucted a red earthenwork at the top of Breed's Hill, a six-foot high breastwork embankment behind which exuberant young ploughboys prepared for the onslaught. The British had heard noises during the night but had failed to investigate, never dreaming so much could be done in such a short time.

|

|

Building Entrenchments |

To decide upon the best course of action, the British called a council of war attended by generals Sir Thomas Gage, the nominal chief, Sir William Howe and Sir Henry Clinton. General Gage was soon to be replaced by Prime Minister Lord George Germain. Germain said of Gage, "with all his good qualities, Gage finds himself in a situation of too great importance for his talents." Howe on the other hand was described as "quiet spoken, intelligent and idle by reputation." Clinton was said to "suffer from shyness and have an almost paranoid inferiority complex."

|

|

Sir Thomas Gage |

|

|

Sir William Howe |

|

|

Sir Henry Clinton |

|

|

Lord George Germain |

The trio decided that the Americans had to be beaten badly and what better way to crush the rebellion than by routing Yankee Doodle Dandy on a battlefield of his own choosing. Clinton favoured the more obvious and more cautious approach of cutting the rebels off from the rear by blocking the narrow neck linking them to the mainland. This was not spectacular enough for Howe and Gage, who favoured a frontal assault. According to Howe the hill "was open and easy of ascent and could quickly be carried." He could not have been more misguided. However despite Clinton's protestations their preference prevailed. Gage and Howe's direct assault on the Americans was based largely on contempt for the enemy's fighting prowess - never the best basis for military success. Meanwhile high above on the hill, the rebels watched and waited.

Gage, who was commander-in-chief of all of His Majesty's military forces in America, had married a New Jersey girl. An amiable individual, Gage said excitment always made him ravenous. He just wanted to keep the Americans quiet and happy until he could retire as soon as possible on full pay. He was recalled after the battle of Bunker Hill. Howe, who succeeded Gage as commander-in-chief, was the key figure and he commanded the attack. Tall, dark, brooding with thick eyebrows, ample hair and a wide, coarse nose, Howe was described as a brave commander. He , defeated George Washington twice, but on the whole was considered "to be self indulgent, ignorant and lacked ability." He showed himself to be conventional and unimaginative and was recalled to England in 1778. Clinton, who succeeded Howe as commander-in-chief, subsequently resigned and sailed home in 1782.

|

|

Sir William Howe |

In addressing his 2300 troops Howe said he was proud to command so fine a body of men and was sure "They would behave like Englishmen and as becometh good soldiers. I do not expect you to go a step further than where I go myself at your head." Howe was as good as his word and led from the front rank.

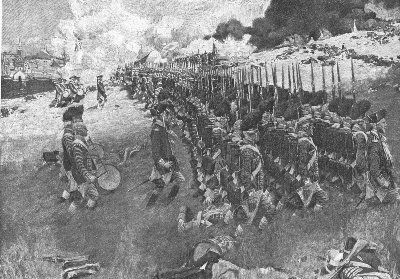

Just before the battle began five deserters were brought before Howe. He ordered two to be hanged on the spot. Their comrades, who were preparing to attack, lowered their heads and looked away. Then up went the redcoats and up went the casualty count.Bunker Hill, a battle that should never have occurred took place on a cloudless day in the early afternoon of June 17th, 1775. Bunker Hill was 110 feet high and just behind it was Breed's Hill, seventy-five feet high. In the full glare of the burning sun the heavily laden British troops carrying 27 kilograms and sweltering in winter gear of thick scarlet cloth, commenced their ascent through knee-high grass up the heights. On their backs they carried a rolled blanket and three days' supply of bread and boiled beef. Each held a heavy, smoothbore, brown Bess musket. Formed abreast in three ranks they advanced up the steep slope in perfect order. In the forefront on the left flank were the grenadiers and on the right the light infantry. In between were infantrymen drilled in the use of the fourteen-inch, three-sided bayonets flashing in the noonday sun. Gasping for breath beneath the burning sun and their heavy burdens, the troops plodded upward. From time to time on command they pointed their pieces in the general direction of the foe and fired, their shots passing harmlessly over the heads of the well-sited rebels.

|

|

Bunker Hill |

All about them was flash and flame as batteries roared and the fleet's cannons thundered. Although not raised high enough to roust the rebels, the cannons' pounding missiles shook their morale, some of the dauntless defenders slipping away to safety as the first blood flowed. Over all hung billowing, black clouds of gun smoke. Riding up and down the lines of his men, the American commander roared, "Don't fire until you see the whites of their eyes! Aim low and take out the officers." The greenest among the gunners were all old hands at hunting and they now took careful "aim at the handsome waist coats" and fired with terrible effect.The red coats were riddled with "lead, horseshoe nails and angular pieces of iron" so as to cause, according to the British surgeons, "infinite pain." The effect of each fusillade was devastating with whole ranks faltering then falling in their tracks. Those lucky enough to survive one salvo, sought to avoid another by attempting to retreat only to be prodded forward with bayonet and sword into the next wasting broadside. The casualty rate was 45%.

Howe in the forefront was not scratched. Recalling his troops Howe reformed the men for another sickening surge. Twice repulsed with appalling losses, the thin red line regrouped and made a third attempt to breach the American positions. With fixed bayonets they charged, shouting and screaming in exultant anger, "stepping over the bodies of comrades as if they were logs," The slope of the hill was red with the litter of scarlet and white. Awed eyes behind the barricades watched the shredded companies and wondered if their riddled ranks could possibly rally. The answer came quickly. Drums beat and once again bloodied British charged through the smoky dusk, "their bayonets eager." American fire "went out like a spent candle" and Colonials skedaddled in all directions, their commander shouting as they fled, "Save yourselves." In retreating the Americans' disorganization cost them most of their casualties. Their dead totalled 100. The British victory had come at a Pyrrhic price for Howe had lost every officer and nearly half of his total command, some 1054 casualties in an hour and a half. They had a hill but no army.

Gage groaned and Howe shook his head. They could not believe it. One British general said it was "one of the greatest scenes of battle that can be conceived." Clinton's comment on the carnage was more accurate."It was a dear bought victory; another such would have ruined us." Howe, who lost all his staff officers, confessed, "When I look to the consequences of the battle in the loss of so many brave officers, I do it with horror. The success is too dearly bought." Burgoyne wrote of the butchery, "Now ensued one of the greatest scenes of war that can be conceived. Howe's corps ascending the hill in the face of intrenchments. The whole picture was a complication of horror and importance, beyond anything that ever came to my lot to be a witness to."

History termed the horror criminally meaningless. It was all for naught for the Americans could easily have been starved into early surrender. Hit and run raids, not volley fire succeeded in the American revolution. The lesson to be learned was to take cover on the skirmish line, dart out to fire at will from behind trees and ditches, then disappear. Basic tactics were few and simple: deception, secrecy, security, surprise and the gathering of intelligence. These could then be put into actual practice by ambushing. British officers stubbornly refused to learn this lesson and needlessly lost thousands of brave men.

Following the battle British troops of the 5th Regiment were shut up in the town of Boston by American soldiers who prevented them from acquiring fresh meat and vegetables. Captain George Harris wrote home about their plight.

In His Own Words"We may block up their port but the rebels have blocked up our town and have cut off our good beef and mutton. At present we are completely blockaded and subsist only on salt meat." The enterprising captain cultivated his own little garden of salads and greens.

Following the revolution companies of the 5th Regiment, nicknamed The Shiners because of their bright appearance, served in Canada from 1787 to 1797. The 5th, which had been at Detroit and Michilimackinac since 1790, was moved to Fort Niagara where it remained until 1796. In 1792 the year of John Graves Simcoe's arrival in Upper Canada, the distribution of the 5th was:

1 company at Fort Erie;

a half company at Fort Schlosser;

8 1/2 companies at Niagara.

At these posts the 5th defended Simcoe's centre for the four years of his tenure, while the 24th Regiment covered the exposed west at Detroit and the 60th Regiment held Fort Ontario at Oswego. By September 1793 the 5th numbered only 17 officers and 265 enlisted men in Fort Niagara and a further four officers and 81 men were at forts Erie, Schlosser and Chippawa for a total of 21 officers and 346 men. These represented approximately three-quarters of the regiment's full strength. The ten companies of the 5th Regiment were divided between eight battalion or centre companies and two flank companies, the grenadiers and the light infantry. Each was led by three officers, usually a captain, lieutenant and ensign with non-commissioned officers and a single drummer for signalling.

|

|

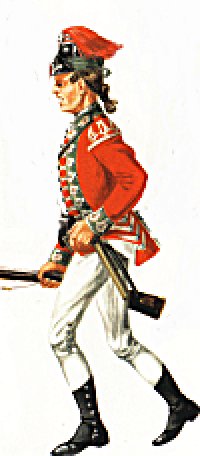

5th Regiment of Foot Light Company |

The following recruiting poster promoted service in the 5th Regiment of Foot.

|

Advertisement for Recruits

His Majesty's Garrison of Niagara

TEN GUINEAS BOUNTY Money will be given to all Gentlemen Volenteers, who are willing to enlisht themselves in His Majesty's 5th Regiment of Foot now in the Garrison of Niagara on being approved of a the Head Quarters of the Regiment, they will be Clothed, accoutred, victuallyed and paid agreeable to His Majesty's Regulations.

Active men such as are fit for Service, not less than 5 feet 5 inches high, between 16 & 40 years of age, will receive every encouragement at the Garrison at Forts Erie and Chippawa, at Queenstown Landing and at the Drum Head.

GOD SAVE THE KING

All British regiments serving in Upper Canada suffered from desertion and the 5th was no exception. Garrison life was dull, tedious and often brutal and the nearby border beckoned. In addition British soldiers were enticed to desert by individuals called 'crimps', agents who provided American employers with cheap labour. Simcoe reported "alarming desertions" from the 5th regiment and attributed these to the men being "shut up in the garrison" for too long a period, their inactivity leading to "a roving tendency." On one occasion the deserters included ten privates, a drummer and a fifer. Native warriors were used to track down, capture and return the deserters and one offered his Native captors his watch and money, but the chief declined the bribe.

Alarming desertions of the 5th Regiment continued, a growing number of them escaping in a boat bringing settlers from the United States to Upper Canada. After American settlers had disembarked from the American ship, too many of the fighting 5th were taking advantage of the opportunity to return to the States on the empty vessel. In July 1793 Simcoe ordered the construction at Niagara of a gunboat "on a large scale" sufficient to carry a 12-pounder. Simcoe hoped his gunboat would eliminate or drastically reduce this floating flight because "this water patrol would provide instant pursuit by oars of sail" to capture the culprits.

A general court martial was ordered to sit upon five soldiers of the 5th Regiiment who deserted their post at Chippawa, but could not find any means of crossing the river and were caught. Simcoe was obliged to report to his superior that while the trial was in session, two more members of the 5th seized the opportunity to desert. He attributed this "continuation of crimes" to the open border and the regiment being shut up in Garrison which encouraged "the roving tendency which too often fixes the mind of the unemployed soldier." Occasionally deserters had second thoughts about severing all ties with their past and they appealled for permission to return to their regiment. Simcoe suggested to Lord Dorchester that "a proclamation of pardon be issued to induce such men to return "to the King's service."

The 5th served also as a police patrol of the border. Around 11 p.m. on May 31st, 1794, a boat bearing contraband endeavoured to slip by Fort Niagara. A sharp-eyed sergeant of the 5th and several privates gave chase only to be fired upon twice "in defiance of the law and in contempt of the Peace of our Lord the King." A reward of 50 pounds was offered for the shooter and the King's Pardon for his partners if they turned him in.

Despite the fact that five border forts - Ontario, Niagara, Miamis, Detroit, Michilimackinac - were on American territory, Britain maintained garrisons at them and indicated that "the posts and the dependent country" roundabout each would be turned over to the Americans only after they had satisfied the term of the peace treaty which required them to compensate the Loyalists for their losses following the revolution. The most important of these posts was Fort Niagara.

In August 1794 it came to Lieutenant Governor Simcoe's attention that Americans were building 'an establishment' in the dependent country not far from Fort Niagara. An outraged Simcoe ordered Lieutenant Roger Hale Sheaffe of the 5th Regiment to proceed with an ensign, one corporal and six privates to the establishment and tell the Americans to "desist from such aggressions."

Sheaffe had commenced his career with the 5th Regiment of Foot and received his commission as ensign on the 8th of May, 1778. [See Below *] Words not weapons were to be used and to avoid any possibility of confrontation and conflict, Sheaffe was advised that "it was not necessary that the men should carry their arms with them but to take 100 rations of provisions."

As American anger and frustration grew over the continued British occupancy of American territory, it was feared war was imminent. On August 13, 1794 Simcoe informed his superior in London that a crisis was fast approaching. He had learned that an American military force under General Anthony Wayne had been given orders to reduce a British post on the Miamis River and the following spring attack Fort Detroit. Faced with a possible assault on the occupied posts, Simcoe acted. He ordered a detachment of the 5th Regiment comprising a captain, a subaltern, two sergeants, a drummer and sixty rank and file to proceed to Fort Erie, thence westwards to Detroit from where an American assault was expected if war did break out.

Later in August Captain John Smith commander of the 5th Regiment at Fort Niagara was ordered "as the wind serves" to embark on board the Felicity with a non-commissioned officer, two sergeants and 30 rank and file and proceed immediately to Detroit. Subsequently Simcoe himself left for the west with a contingent of Queen's Rangers and a complement of the 5th Regiment usually garrisoned at Fort Erie, Chippawa and the Landing at Queenston. According to Joseph Brant, Grand Chief of the Six Nations, who also intended to leave for the west with a party of warriors, "our fate depends on the repulse of Wayne." Wiser heads prevailed, however, and Wayne withdrew his forces without firing a shot at the British flag.

All the while during this tense time, negotiations were taking place in London in an attempt to resolve the problem and prevent war. In 1796 these negotiations finally resulted in "Jay's Treaty" by which Britain agreed to withdraw its garrisons from all the occupied posts. For eighteen years this Treaty of Amity preserved the peace between Britain and the United States. Following the signing of the treaty, the commanding officers at the five forts were ordered "to proceed in evacuating their respective posts completely with all convenient speed taking care to prevent all disorders."

A general order dated June 2, 1796 ordered a detachment of the 5th Regiment to evacuate Fort Niagara and turn it over to the forces of the United States of America with all convenient speed. Officers were cautioned to take care "to prevent any disorders." Captain Roger Hale Sheaffe of Queenston Heights fame was the officer in charge of this assignment. As soon as the garrisons had been withdrawn, the commanding officers of the Fifth were told to embark their Corps and were "ordered down to Quebec with all convenient speed."

As of August 1, 1796, the state of Fifth Regiment troops in the province of Upper Canada included: Major Shank, Niagara: 1 captain, 2 lieutenants, 2 sergeants, 1 drummer and 66 privates.In the Royal Warrant of 1768 eight distinct colours of regimental facing were specified - blue, yellow, green, buff, white, red, black and orange. Military coats were faced or lined with a different colour from the basic colour of the coat. Facings included: lapels, collars, cuffs and the lining of the coats. The 70 regiments of infantry each had a specific colour assigned to it. Royal regiments always had blue assigned as their facing colour.

Like all British army uniforms the 5th's regimental dress was scarlet. The facings were "gosling" or pale, dull green, the lace plain white and the waistcoat and trousers were white with black knee-length gaiters. The uniform was topped off by a grenadier (fusilier) felt cocked cap embellished with a red and white hackle plume worn on the left side to commemorate the Regiment's victory over French grenadiers at St. Lucia in the West Indies. [**]

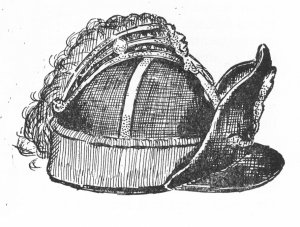

In 1771 a light company was formed in every battalion of the British infantry. When the light companies were established, the regulations prescribed their uniform. To enable these companies to move quickly, to take cover and to employ stealth when required, their uniform and equipment were modified. Coats were reduced to jackets; short gaiters and hats were replaced with leather caps. Their equipment consisted of cross-belts carrying a ball bag

|

|

5th Foot Light Company Cap 1780 |

on the left, a powder-horn on the right and a waistbelt with a double frog (loop) for bayonet and hatchet. On its front was a small cartridge pouch to contain nine rounds. Sometime after the war in North America, the uniforms were stripped of lace trimming (gold or silver thread). Troops received uniform clothing annually, the cost withheld from the pay.

The 5th Regiment was the only Fusilier (a regiment armed with a fusil, a light, flintlock musket) corps authorized to wear a plume. [***] All belts were pipe-clayed and all buttons were bright. Pewter buttons of enlisted men found at Fort Niagara bear an Arabic numeral '5' within a broken circle. Earlier buttons of the same regiment found at Michilimackinac contained a Roman numeral 'V'. Officers' buttons were silver-plated and bore the Roman numeral 'V' encircled by the laurel-wreath.

|

|

Buttons of 5th Regt: Roman Numerals - Officers; Arabic Numerals - Enlisted Men: |

Regulations concerning the appearance of infantrymen were very strict. Hair had to be powdered or made white with a mixture of whitening and pomatum, an ointment hair dressing made from apples. The daily ration of the regular soldier consisted of 1 pound of flour, 1 pound of salt pork, 4 ounces of rice and a little butter. This cost 6d. a day which was deducted from the soldier's pay.

In 1782 in order to stimulate recruitment it was decided that regiments were to be identified with individual English counties. Thenceforth, the 5th was styled the 5th Northumberland Fusiliers Regiment of Foot. Its motto was Quo fata vocant - Wither Fate Calls. The 5th was also entitiled to several special distinctions. The centre of the King's Colour and three corners of the gosling green regimental colour, both of which were carried at Niagara, were emblazoned with a representation of "St. George killing the dragon." This was also painted on the drums and included along with the king's crest on grenadier caps. The 5th Regiment once included among its members, Phoebe Hassell, a famous female soldier who was pensioned off by George IV. She is commemorated by a monument in the churchyard at Hove, Brighton.

On returning to England in 1797 the 5th Regiment was dispatched to Europe where it fought under the Duke of Wellington, who described its performance

In His Own Words"a memorable example of what can be done by steadiness, discipline and confidence."

The 5th Regiment returned to Canada and served on the frontier during the War of 1812. Thence back to Europe where it served with the army of occupation in France until 1818. The regiment's battle honours include the Peninsula, Afghanistan, and Khartoum.

[*] Roger Hale Sheaffe ensign 5th Regt.1778; lieut. 1780; Capt. 1795; major general 1811; baronet Dec. 1812; administrator of Upper Canada, 20 Oct. 1812-18 June, 1813. [**] According to Captain Michael F. Monahan, Grenadier Company, His Majesty's Fifth Regiment of Foot (In America), a member of a re-enactment unit that portrays the Fifth in the American War for Independence, this statement is not quite true. He says: "It is true that the Regiment did indeed wear the white plume to commemorate the victory of St Lucia, however the red over white distinction did not come about until 1829 when King George IV ordered all infantry to wear the white plume in their head dress. It was determined that this would make the Fifth's plume won in battle next to worthless and so the distinction of red over white was awarded to the Fifth." [***] Captain Monahan also provided the following information in this connection: "The Fifth Regiment of Foot did not become a Fusilier regiment until 1836 I believe. They were designated as the Fifth Regiment of Foot from 1751 until 1782 when the County affiliations took place and they became the Fifth (Northumberland) Regiment of Foot. 1836 brought about the title Fifth Regiment of Foot (Northumberland Fusiliers) and then in 1881 they became the Northumberland Fusiliers. 1935 saw them titled the Royal Northumberland Fusiliers. The amalgamation of 1968 joined four Fusilier regiments to form the Royal Regiment of Fusiliers of which the Northumberlands were the senior unit."Copyright © 2013 Website Administrator