foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

THE FOUNDING OF YORK JULY 1793

History is a pageant for the purpose of satisfying our curiosity.

On Saturday, August 7th, 1993 John Graves Simcoe and his wife, Elizabeth Posthuma Simcoe, landed amid pomp and pageantry at Harbour front in Toronto. As the performers playing these parts stepped ashore, they were greeted by Timothy Simcoe Vowler and Laurie Simcoe Vowler, sixth generation descendants of the province's first lieutenant-governor and his stalwart wife. This re-enactment of the Simcoes' arrival on the shores of the site that became Upper Canada's capital was held to mark the bicentennial anniversary of the founding of Toronto.

Flashback to Monday, July 29th, 1793 as the Simcoes prepared for their trip to Toronto. The Governor had decided that Newark, the colony's little capital located in a clearing on the western shore of the Niagara River, was much too close to the cannons at Fort Niagara. While a British garrison still occupied that fort it was fully expected that before long Britain would have to relinquish control of it to the Americans. Fear of war with the United States was very real and if it came the capital would be very vulnerable to the guns that glared from across the river.

As far as Simcoe was concerned Toronto was to serve only as a temporary capital and instead would become the province's permanent military and naval arsenal. Simcoe had earlier decided that the ideal place for the province's permanent capital would be what he variously called New London and Georgina situated at the present-day site of London on the River Tranche which he renamed the Thames. Simcoe considered the location "was eminently calculated for the metropolis of all Canada." Lord Dorchester decided otherwise. In 1787 he had met with the Chiefs of the Mississauga Indians to purchase the land at the foot of what is now Dufferin Street, Toronto and the land north on either side of a trail to Lake Simcoe. Dorchester designated the seat of government for Upper Canada would be located here.

|

|

The Toronto Purchase 1787 (8) |

Simcoe's choice for the colony's capital was not to be. This plan like so many of his others never became a reality. The capital of the colony designated by Dorchester was to be at the fringe of the forest of primeval oak that overlooked Lake Ontario.

Lord Dorchester ordered Simcoe to visit the area in May, 1793 and to select a suitable location for the colony's capital. The site chosen by Simcoe was somewhere between the Don and the Humber Rivers. It had an excellent harbour for the bay was sheltered by a long marshy point, a peninsula that extended from the shore by a narrow neck of land. In 1858 the neck disappeared beneath the lake as a result of a series of storms and this created the Eastern Gap which is today Toronto Island.

|

Mrs. Simcoe and the Governor had intended to sail across the lake on the morning of the 30th but the wind was unfavourable. That evening after dining with Chief Justice William Osgoode, the Simcoes went for an after-dinner walk from which they were hurriedly recalled around nine o'clock to take advantage of the fair wind that had sprung up. The Governor decided that he would make the trip later so Mrs. Simcoe embarked alone, boarding the boat as the band of the Queen's Rangers played a summer serenade of jaunty martial music on its deck. The vessel Missassagua, a topsail 120-ton schooner, mounted six guns and carried a crew of fourteen under the command of Captain Jean Paptiste Bouchette.

|

With a favourable gale filling its sails the ship disappeared into the blackness, its destination a small clearing on the forested shore across the lake. Mrs. Simcoe retired immediately and under an easy sail slept soundly. When she awakened at eight o'clock the next morning, the schooner lay safely at anchor in the harbour of Toronto, piloted there by Jean Baptiste Rousseau, one of the earliest settlers in the area. Rousseau lived close by and became a general merchant as well as a fur trader when the English settlement began.

Elizabeth gazed for the first time at the shore on which the capital of Upper Canada was soon to rise. She was impressed with what she saw.

In Her Own Words"I have never seen a more magnificent stand of oak than that along the shore. And see how crystal-clear the water is." The tall timbers lining the margin of the lake were reflected on its glassy surface makde it all "very pleasing." The great trees gave the area a sheltered look and screened off the adjoining swamps which when drained would "afford fruitful meadows and good grass."

Simcoe had earlier decided to situate the town site in a grove of oaks on a rise of land overlooking the lake. The Queen's Rangers were already busy felling the fine oak and in the small opening they cleared the soldiers had pitched Simcoe's canvas house not far from the site of what today is Fort York.

|

|

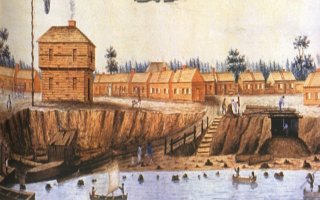

Fort York 1804 |

In the summer season the area was occupied by great flocks of water fowl, their numbers so immense, complained Mrs. Simcoe, their sounds "annoyed us during the night."

|

In 1787 Lord Dorchester decided that the settlements of Loyalists near Niagara and those east of Cataraqui needed to be connected so he directed Sir John Johnson to purchase "a free and amicable right" for the government to the adjacent lands not yet acquired on the north shore of Lake Ontario. Accordingly on September 23rd, 1787 at the Carrying Place on the Bay of Quinte, John Collins, Deputy Surveyor-General, purchased on behalf of the government from three Mississauga chieftains a tract of land known afterwards as the 'Toronto Purchase,' for which the Aboriginals received 1700 pounds in cash and goods which included shrouds, hoes, shot, powder, guns, brass kettles, tobacco, knives, looking glasses, linen, laced hats, pieces of ribbon, fishhooks, gun flints, flowered flannel, blankets, broadcloth, serge and rum.

The Governor proposed fortifying the western tip of the "spit of sand" with a storehouse and blockhouse to be armed with sufficient fire power to deter any enemy vessel either from entering or remaining within the harbour. Constantly cautioned by London to be as economical as possible, Simcoe was forced to seek out weapons wherever they could be found. Among the armaments he used to fortify the harbour were two "good guns," twelve and eighteen pounders that had lain beneath the lake where they sank"after the last peace."

The Simcoes' two-roomed tent, which was sheathed by boards against the coming winter, was pitched in the small clearing where years before a French trading post had stood. The canvas house served as the nucleus of the new community and it became known both for the genial hospitality of its gracious host and for its peculiar structure. From the clearing in which it was located an Aboriginal path led through the trees to the upper lakes. Down this path on August 26th, a group of Native chiefs came calling for a council with the English governor. The Aboriginals, who had come from the shores of Lake Huron, recalled that some time before a great French leader had come to the same spot where fur trading had been carried on. Here the French had "kindled a fire," which to the great surprise of the Aborigines had long since been extinguished.

Fort Rouille - Toronto - York

"Here, when the treasures of the forest vast

Of meadows, streams and pools met their wide gaze,

The Frenchmen built a post, that here might come

Those wily craftsmen that could circumvent

The laws of Nature, and beguile her wealth

Into their packs;

And here they came - to Rouille, through the vales

That skirt yon river with rich woods and deep

From source to sea."

The Frenchmen left never to return. The Natives expressed the wish "that the great man now here would rekindle the fire whose chimney would be strong and never extinguished." They got there wish. The whiteman was here to stay.

In Europe meanwhile in May, 1793 the Duke of York, second son of George III and Commander-in-Chief of the Army, defeated French forces at the siege of Famars in Flanders. News of this military victory reached Simcoe at Toronto in August, 1793 and to celebrate the great event Simcoe issued the following General Order. "On the raising of the Union Flag at 12 noon on August 27th, a Royal Salute of Twenty-one guns is to be fired to be answered by shipping in the harbour in respect to his Royal Highness and in commemoration of the naming of this harbour from his English title, York."

That day the twelve and eighteen pounders scrounged by Simcoe boomed out the birth of York. Several rounds from a party of Queen's Rangers responded as did Aboriginal onlookers who enthusiastically joined in the celebration by firing their muskets. Guns from the ships in the harbour shared in the shooting that christened this wilderness site now officially known as York. The Ojibways were "much pleased" with the revelry and the chiefs were most impressed with the bravery of the Simcoes' little son, Francis, who never flinched at the blasts. One caught the boy up in his arms and held him high in the air delighted that so small a child was unafraid of the fearsome roar of the cannons. Elizabeth Simcoe recorded in her diary that the day was hot and humid, the heavy atmosphere causing the smoke from the ships' cannons to "run along the water with a singular appearance."

Thus was founded Ontario's new capital whose new name never had the unanimous approval of York's early citizens. A bill was introduced in the House of Assembly in 1804 to restore its "more familiar and agreeable name." No action was taken on it, however, and York remained its name until the city was incorporated in 1834 as Toronto.

|

Copyright © 2013 Website Administrator