foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

THE FIRST NATIONS

History is the world's court.

A major reason for the tension in Upper Canada in 1794 was the unrest of Native tribes in the Northwest Territory. They were on the warpath because of the encroachment of Americans on Aboriginal lands. From George Washington's time onward, Americans used every opportunity to thrust the Native tribes westward in their relentless drive to acquire ever more land. Native peoples were pressed inexorably to abandon their homes and heritage in the face of the insatiable demands of American settlers for land. As Robert Hamilton stated in a letter dated January 4th, 1792 to Simcoe

In His Own Words"The Americans seem possessed with a species of mania for getting lands which has no bounds. Their Congress, prudent, reasonable and wise in other matters in this seems as much infected as the people."

While Native North Americans could not stem the flood of white newcomers who multiplied at such a staggering rate, they did strike back in anger at the white onslaught using large-scale violence. In addition to set-piece conflicts there was the risk of skirmish, ambush and slaughter of both whites and Natives. Raids on the settlements wreaked vengeance on white squatters. Americans attributed much of this mayhem to the subversive activities of British Indian agents urging the Aborigines on and keeping them well supplied with guns, ammunition and war paint. They completely ignored their own cavalier contempt for boundary treaties solemnly signed by their leaders and the sachems. The raids seemed anarchic and mindlessly cruel, but cruel as they were as war always is they were less mindless than the message written in blood and flame.

In addition to being charged with fostering frontier fighting in the west, Britain was faulted for its failure to relinquish the northwest posts on American territory. Both these irritants festered in the minds of Americans and as terror and tensions grew, it appeared to many that the two countries were poised on the brink of war. In these tense times, the friendship of Native warriors was very important. Both Britain and the United States vied for the allegiance of the various tribes, sparing neither energy nor expense to win them over. In New York this included paying a dollar a head to Iroquois braves, who were invited aboard a French ship to see the guillotined semblance of Louis XVI's severed head dripping blood. Britain had Joseph Brant's leadership to thank for keeping the Six Nations true to the King's cause. Both countries contrived in every way they could, to create jealousies and divide Native loyalties. Washington charged that Britain was

In His Own Words

"Seducing tribes that we have hitherto been keeping at peace at a heavy expense and who have no cause for complaint."

Despite Britain's close friendship with Brant and the tribes of the Six Nations, William Johnson, British Superintendent of Indian Affairs, admitted that fair and equitable treatment of the Aborigines was difficult to provide, because it frequently conflicted with the interests of leading men in the province. Merchants with investments in land speculation as well as local sheriffs and justices of the peace hindered government efforts to secure just treatment for the Aborigines.

Although land was bought and treaties were signed by British officials, the land deals were often defined in the vaguest of terms. For example, northern boundaries were determined by how far a person could walk in a day or by how far one could hear the sound of a gun fired from the lakeshore. The First Nations received very little for the immense tracts of land they ceded. In 1784, the Mississaugas gave up 3 million arcres along the Niagara Pensinsula for less than 1200 pounds worth of gifts. British negotiators were always cautioned "to pay the utmost attention to Economy."

The increasing loss of their land to white settlers was a source of continuing concern to the chiefs of the various tribes. They were aware of the ongoing negotiations between the American John Jay and his British counterpart, and they eagerly awaited the terms of the treaty, hoping it would include provisions to protect them and their lands from further encroachment by whitemen. They waited in vain for while the treaty referred to Aboriginal trade, it omitted any mention of Aboriginal property rights. The Natives had backed the losing side and were now at the mercy of whites on both sides of the border. Many tribes saw the extinction of their way of life "written on the wind."

While they readily admitted that Native warriors had bled freely for the King, the British proceeded to sacrifice the interests of their Native allies to the cause of accommodation with the Americans. If the Aborigines now intended to confront the Americans to preserve what was left of their lands, they would simply have to shift and shoot for themselves. In the United States an important source of government revenues came from the sale of land to settlers. This was land purchased for a pittance from the Aboriginal owners. As time passed tribal chiefs became less willing to sell their lands to scheming individuals for mere baubles and beads. The Americans were quick to realize this. "It is no secret that the Indians are beginning to appreciate their lands, not so much for the use they make of them as by the value at which they see them estimated by those who purchase them."

As a consequence of this realization, purchasing land from the Aborigines became more complicated and costly. This resulted in some American government agents making deals fraudulently with renegade representatives of the tribes, or bribing chiefs with dollars and drink to get them to make their mark on official documents. Often land speculators simply claimed Aboriginal lands before government agents had completed their negotiations, and then provoked the Aborigines to do something about it. When warriors responded with force to protect what was theirs, the army was called in to "rescue"the American interlopers. Defeat usually followed and the chiefs were then forced with punitive treaties to sign away their lands. This pathetic pattern was repeated throughout the period of American's westward expansion.

"The Indians should be made to smart," declared the American general Arthur St. Clair. Congress agreed and appropriated a million dollars for a federal army to fight the western tribes. St. Clair marched to the Wabash River southwest of Lake Erie where he met a force of Shawnees and Miamis and was severely defeated. This convinced the American government that the union of the western tribes had become too powerful to ignore and stronger forces would be required. Prior to any military action, however, half-hearted negotiations usually preceded the use of force in order to convince public opinion at home and abroad as Jefferson put it,

In His Own Words"that Peace was unattainable on terms the Indians would agree to."

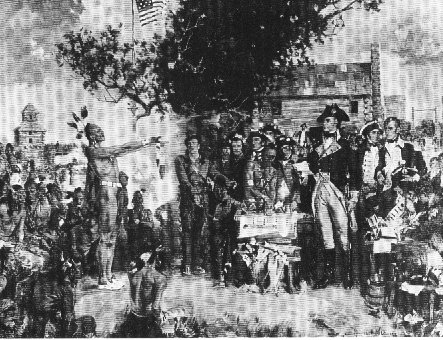

When an important peace parley failed, American commissioners sent a coded message to a waiting general:"We did not effect peace." The general translated this into "Begin vigorous offensive action." This occurred at a place called Fallen Timbers on August 20th, 1794, when the army of Major-General Anthony Wayne met and defeated a large force of western Natives. Subsequent to this defeat, some 110 chiefs and warriors signed the Treaty of Fort Greenville in August 1795. By this treaty, the most important Indian treaty in the history of the United States, the sachems and War Chiefs gave away 25,000 square miles, today most of present-day Ohio, part of Indiana and the sites of Detroit, Chicago and a number of other mid-western cities for 25,000 dollars in trade goods - calico shirts, farm tools, trade hatchets, ribbons, combs, mirrors, and blankets and an annuity of $9500 to be divided among the tribes. It was a humilitating settlement with payments that were a pittance. Some tribes received as little as $500 a year. Few could challenge its terms for when Wayne destroyed their fields, many became dependent on the United States for food. When a calumet or peace pipe was smoked by the parties to cement the terms of the treaty, the ceremony was ridiculed by one American negotiator as "a tedious routine."

|

|

Treaty of Fort Greenville |

From a precontact population in the millions, by 1900 the number of Native peoples remaining numbered some 250 thousand. Their dispossion makes melancholy reading. The grim truth was that when two peoples competed for the same land, the stronger prevailed and the weaker simply had to accept whatever terms they could get. In return for this huge tract of the fertile frontier pledges were given that the remaining lands would be left to the Native owners. It was not to be, of course, for the tide of white settlement was unstoppable.

Joseph Brant, Chief of the Six Nations, hoped it might not be too late to salvage something.

In His Own Words"I know that to complain of what is past will not ensure an absolute redress, but I believe it may be useful to reflect upon past errors and to discuss the malconduct of public officers whereby important injuries have been done to Indians."

Others like Chief Cornplanter thought it was already too late.

In His Own Words"Brothers, we have scarcely place left to spread our blankets. You have taken our country."

Alone among the sachems, the great Shawnee Chief, Tecumseh, refused to sign the treaty. Tecumseh was a man of remarkable intelligence and ability. Noble in speech and behaviour, this great orator was farsighted, brave and merciful towards his captives.

In His Own Words"So live your life that fear of death can never enter your heart. Seek to make your life long and its purpose in the service of your people. Show respect to all people and grovel to none. When you rise in the morning give thanks for the joy of living.

Tecumseh raged against the sale of lands long held by the Aborigines. "Sell a country! Why not sell the air, the clouds, the great sea as well as the earth? Did not the Great Spirit make all for the use of his children? Our fathers from their tombs reproach us. I hear them wailing in the winds. We are determined to defend our land, and if it be the Creator's will, we wish to leave our bones upon it."

|

|

Tecumseh at the Battle of The Thames |

Tecumseh did just that. With painted face and tomahawk held high, he fell fighting from a load of buckshot in the breast near Moraviantown at the Battle of Thames. So died one very brave heart. As sunset faded into darkness, his faithful warriors stole like spirits through the woods and bore his body away. His people revered him as the white men revered Brock, but their grieving saw no flags lowered, no martial music mourned his death, no stately monument marked his final resting place. They buried him stealthily by the light of flickering torches, his grave quickly blanketed by the falling autumn leaves, lost forever in the mists of time.

"Slowly and sadly we laid him down,

On the field of his fame, red and gory,

We carved not a line and we raised not a stone

But left him alone in his glory."

In 1931 a Grand Council approved a resolution declaring that bones preserved on Walpole Island were, in fact, the actual bones of Tecumseh. Whether they are or not no one can know for certain. Money was raised and the bones buried under a simple monument which overlooks the St. Clair River at the junction of the main road to the Island and River Road.

In June 2003 on the Chippewas of Kettle and Stoney Point First Nation reserve, a monument featuring four life-sized bronzed statues honouring First Nations veterans was unveiled. One of the bronzed figures is of the great chief Tecumseh, "who was killed while fighting alongside British troops in 1813 against American invaders about 45 minutes from the reserve." The statues, which include a First Nations servicewoman, a Canadian soldier and an American soldier are set atop a giant turtle representing the Earth and the long life of Native peoples.

Copyright © 2013 Website Administrator