foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

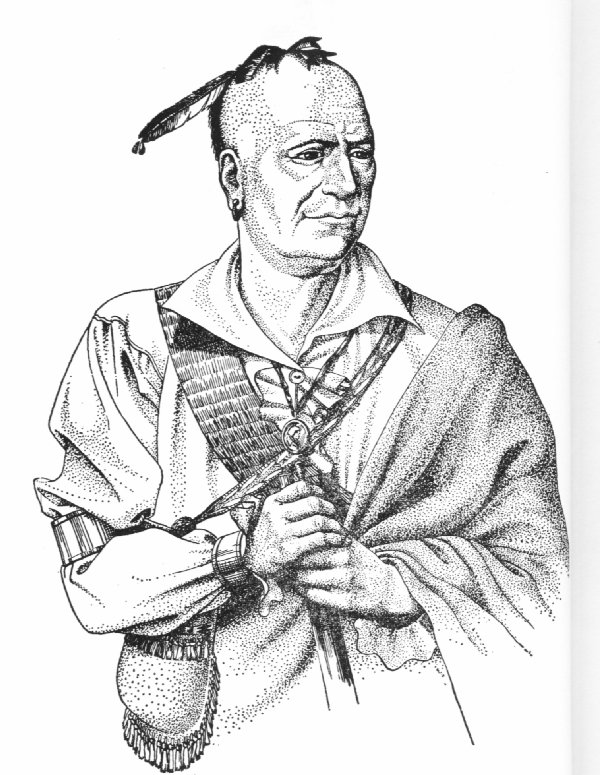

THAYENDANEGEA - JOSEPH BRANT

History is the record of encounters between character and circumstance.

"If you have any influence with the great, endeavour to use it for the good of my poor Indians."

|

|

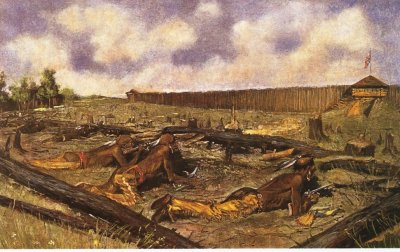

Thayendanegea (16) |

Thayendanegea, Chief of the Six Nations, wisely warned his people to foster

"unity and concord among themselves"

Thayendanegea, "he sets or places together two bets," [*] was born in the spring of 1742 in what today is Ohio on the banks of the Muskingum River. His father, a prominent warrior, died when his son was an infant. Joseph Brant, his English name, became a figure of distinction, a remarkable man. The young Mohawk was educated in English at a school in Lebanon, Connecticut under the tutelege of Dr. Eleazar Wheelock, the founder of Dartmouth College. Described by his teacher as being "of a sprightly genius, a manly and genteel deportment, and of a modest and benevolent temper, Brant was soon employed teaching the Mohawk language to fellow scholars planning on working with the Indians. Later he became an interpreter with Indian Affairs.

When war broke out between Britain and France in 1756, the Iroquois allied themselves with Britain. The People of the Long House had long memories. They remembered that in 1609 Champlain had joined forces with a war party of Montagnais, Algonkins and the Huron warriors and defeated the Iroquois at the site of what later become Fort Ticonderoga. Champlain then added insult to injury in 1615 when he supported the Hurons in an attack on a Mohawk village in New York.

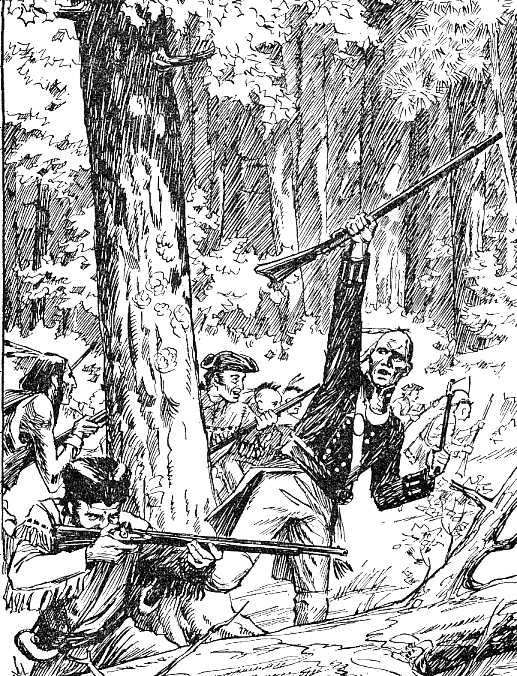

At 15 years of age Joseph joined other Mohawk warriors when they supported the British invasion of Canada by way of Lake George. Joseph later confessed to his sister, Molly, that he was so frightened by the tumult and the terror of battle, he had to hold onto a tree to keep from fleeing. He stayed and fought and soon became a warrior to be watched. In 1757 he was given a commission as captain in His Majesty's Royal American Regiment and as a British officer he fought the French at Fort Niagara under forces led by Sir William Johnson, the British superintendent of Indian Affairs. The British won and the Union Jack snapped in the breeze over the fort for the next thirty-seven years. Brant also fought in a force led by Jeffrey Amherst that besieged Montreal.

|

|

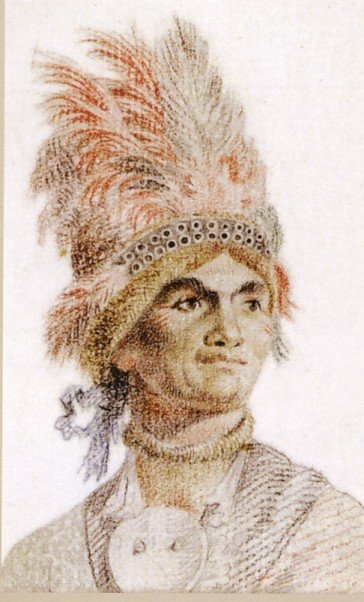

Joseph Brant in his new dignity as a British Officer with Native embellishments and Mohawk scalp-lock |

|

|

Joseph Brant (15) |

When the American War of Independence began, the Iroquois found themselves in a difficult situation. Their long-standing alliance with the British was still in effect, but their ally had now divided into two warring camps. Both recognized the strategic importance of the Iroquois and sought of the Six Nations. The Iroquois faced two questions regarding their own interests: (a)which side was more likely to win? (b)which side would be more likely to protect their interests? Certain of no simple answer and unable to come to a unified decision, they convened the Council Fire of the League at Albany in August 1775. They decided "not to take any part" in a war they deemed "a family affair." However, like so many of the decisions taken by the League, this one was not unnanimously honoured. The spirit of the agreement was observed only by the Oneidas and the Tuscaroras.

The other four members of the confederacy yielded to the powerful influence of Sir William Johnson and of Daniel Claus, a son-in-law of Sir William and deputy superintendent under Colonel Guy Johnson, who was also a son-in-law of Sir William. The Cayuga, Onondaga and most of the Seneca joined the British. Deciding that they did not want to be left out of the coming conflict, the Oneida and Tuscarora sided with the Americans.

|

|

Sir William Johnson (left) & Col. Wm Claus |

The Mohawks chose to support the British because American colonists were already overrunning their lands. The alliance was not unnatural as far as the Natives were concerned. For more than a hundred years, the Iroquois League had allied itself with the British in their long conflict with the Algonquins. Brant, Mohawk chief, had fought alongside the British in the Seven Years' War and he remained loyal to the redcoats. This new alliance was really just a continuance of their long-standing cooperation.

Brant championed the British cause and promised to ally his warriors with their army. Little wonder that when he visited England in 1776 with Guy Johnson, Sir William Johnson's successor, to present their position on Indian Affairs, Brant was honoured and feted by the leading men in the arts, letters and government. He met James Boswell, the famed biographer of Samuel Johnson, who noted this in his journal. "The present unhappy civil war has occasioned Brant coming over to England. His manners are gentle and quiet. He had promised to put three thousand men in the field."

Lord Jeffrey Amherst who had been commander-in-chief of the British forces in America gave a dinner in Brant's honour. In his toast Amherst referred to Joseph as "His Majesty's greatest American subject." In his response to the toast Brant said, " Among the Indians there are two roads to greatness. One is the warpath and the other is the council. The council road is the most famous because fewest are able to travel on it. Almost any Indian can be a warrior. That is all I have ever been. Even in that I have never been anything but a subordinate under warriors much greater than I can ever hope to be such as Hiakatoo of the Senecas or King Hendrick whose fame you all know."

The King gave Brant two audiences, the second of which was recorded in the Court Journal. "The sachem of the Iroquois of North America was presented to His Majesty and the Queen by the Secretary of State for war." Brant's portrait was painted by Romney the noted portrait artist of the day. Brant complained to British government officials that the whites were encroaching on the little land left to the Natives. |

|

Joseph Brant |

Lord George Germain, the secretary of state for the American colonies, promised Brant that after the dispute with the king's rebellious colonies had been settled, Brant could be assured "of every support England could render them." Germain's promise satisfied Brant and convinced him that the Natives' welfare lay in continuing their alliance with the king.

|

|

Lord George Germain |

|

|

Guy Johnson, Superintendent of Indian Affairs & Captain Joseph Brant, Grand Chief of the Six Nations |

Brant fought with fierce determination against the Americans on the frontier and distinguished himself as one of their most courageous warriors and ablest strategists. His contribution to the cause did not go unrewarded. Of Brant's loyalty and leadership, Lord Germain wrote, "The astounding activity of Joseph Brant's enterprises and the important consequences with which they have attended give him a claim to every mark of our regard." In 1779 Brant received a commission signed by the king as 'captain of the Northern Confederate Indians' in appreciation of his "astonishing activity and success" in the king's service. Even though he esteemed his rank as captain, he preferred to fight as a war chief.

Brant's excellent leadership was not lost on the white militiamen many of whom were eager to serve under him. He was "a person in whom they had confidence and voluntarily served under with much satisfaction." [******] {Official dispatches revealed him to be "the perfect soldier, possessed of remarkable stamina, courage under fire, and dedicated to the cause, an able and inspiring leader and a complete gentleman." Fort Niagara was never attacked during the conflict, but it was used as the base for a score of damaging attacks by Loyalists and their Indian allies led by Brant who wreaked havoc on American forces throughout New York and Pennsylvania. The Native warriors and their leader were a most reliable and effective ally.

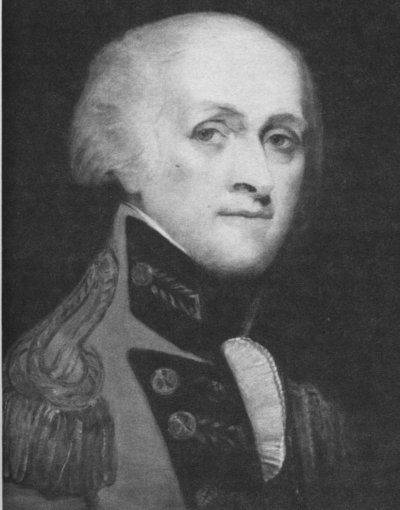

Despite numerous local successes, time and tawdry British leadership took its toll and it became increasingly evident to the Aboriginals that the Americans were going to win the war. Early rumours of the British surrender naturally increased the foreboding of the Iroquois about their fate in face of defeat. Their support for the British had forced them to vacate their former homes and hunting grounds in the Mohawk Valley in New York. Their existing home on the east side of the Niagara River in the vicinity of the old landing place above Fort Niagara would soon cease to exist. The Iroquois elders grew increasingly apprehensive about their fate. Their worst fears were well founded once the peace talks began. The British negotiators were no match for the men representing Congress. What the Americans had failed to win on the battlefield, they quickly acquired at the negotiating table. The losses of the British Loyalists were given short shrift, and land for the Longhouse Loyalists was never a consideration. Military correspondence revealed that the British had attempted to prevent the disclosure of this information from their Indian allies, but word leaked out. "The preliminary articles of the peace treaty (the Treaty of Paris of 1782 that terminated the American Revolution) which were concealed from the Indians have now burst out."

The task to tell the Natives fell to Major Ross, the leader of the last Tory-Indian raid in the Mohawk Valley. He informed Major General Sir Frederick Haldimand, Governor General of Canada, that he would use every means to console the Indians "whose resentment grows." When Brant learned the treaty terms, he angrily exclaimed that England had "sold the Indians to Congress." As the Iroquois contemplated all they had lost and reflected on their future, they came to the sad and angry conclusion that their sacrifices had been in vain.

|

|

Sir Frederick Haldimand, Governor General of Canada |

The more the commanding officer at Fort Niagara, General Allan MacLean, thought about it, the more he recognized that the Six Nations had every right to be outraged. When the Iroquois sachems learned of the new boundaries for the United States, they could not believe the British would be so treacherous and cruel to an important ally. The King had ceded land to the Americans what was not his to give and the Americans had accepted from the sovereign what he had no right to grant. The Aboriginals were a free people subject to no power on earth. They were allies of the King, not his subjects. He had no right to grant to the Americans their entitlements or properties. They would not submit to it. Joseph Brant was quoted as saying that England sold out the Indians to Congress and his people might by and by retaliate, for they too could ingratiate themselves with Congress.

When Brant's military career ended, his career as a statesman began. Joseph Brant was a chief of chiefs. The Six Nations made up of the Mohawks, Senecas, Oneidas, Cayugas, Onondagas and Tuscaroras formed a confederacy of Natives on the continent of America and Brant was their chief. Each tribe had its own chief, but Brant was the chief of the united tribes. Brant exercised dynamic leadership and won the confidence of both white authorities and traditional leaders in diplomacy as well as in war. He was a key spokesman for the Iroquois when they confronted colonial officials about Native concerns over property.

The indignation of the Six Nations at their betrayal resulted in British administrators in Quebec hurriedly attempting to mollify them by various means. Haldimand reiterated that the government would uphold its guarantee that all Native Loyalists would have their land restored when hostilities ceased. He knew all too well the dangers involved and did not wait to relieve the mounting tension of the Iroquois. He instructed Sir John Johnson, son of Sir William and his successor as Superintendent of Indian Affairs, "to quiet the apprehensions of the Indians by convincing them it is not the intention of the government to abandon them to the resentment of the Americans."

|

|

Sir John Johnson |

He dispatched Major Samuel Holland, Surveyor General of Canada, to examine the north shore of Lake Ontario with a view to settling such of the Six Nations as preferred to remain in Canada rather than return to their former habitations and be suject to the power of the States.

|

|

Samuel Holland |

Brant had earlier declined an invitation from the Senecas to the Mohawks to make their residence at Buffalo Creek because this would have taken them south of the Canadian border and exposed the entire Longhouse to attack by the Americans. Most of the Mohawk warriors had been killed and futher losses would imperil the existence of the tribe. They had had enough of war and looked to Haldimand for help in finding a homeland.

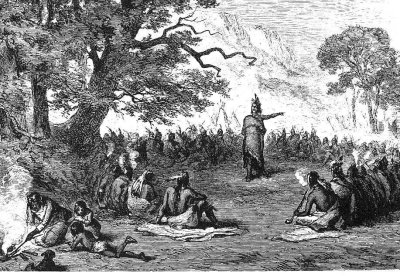

Chief Brant met with Haldimand at Quebec and inquired whether Britain would replace the land they had lost as allies of the King? Haldimand was sypathetic to this request for he wished to avoid another Native uprising similar to the one led by Pontiac, chief of the Ottawas. Pontiac had successfully welded together a coalition of many Native tribes south of the Great Lakes and east of the Mississippi in a united resistance against encroaching English settlers.

|

|

Pontiac in Council |

During what has been called Pontiac's Rebellion, the Indians killed seventy-two redcoats in battle above Niagara Falls and massacred two thousand white settlers. The uprising quickly turned into a stalemate since Pontiac failed to capture Detroit and Lord Amherst was unable to make good his vow to extirpate the savages once and for all. The whites'old ally, disease, broke the deadlock. After a smallpox epidemic decimated the Ohio tribes Pontiac agreed to a powwow with the British on "the middle ground." A deal was brokered and a settlement reached in 1766. The British resumed their gift-giving and ensured peace would be guaranteed by their common father, King George.

|

|

Pontiac Stalks |

Although Pontiac's rebellion was eventually crushed, Governor Haldimand wanted no repetition of that uprising. To avoid that possibility Haldimand eagerly accepted Brant's proposal that a colony of Native Loyalists be located on the settlement frontier of British North America where they could if necessary assist in blocking any future American encroachments. Implementation of this plan was initiated in the spring of 1783 when a settlement was proposed on the fertile shores of the Bay of Quinte near present-day Belleville, With a gracious flourish Haldimand offered this land to Brant who accepted it. Two Mohawks, Joseph and John Deseronto, quickly gathered together some three hundred Mohawks who settled on the site and began to build a new life on their new land. [***]

Joseph Brant recalled Pontiac whom he had seen in Detroit in 1763 but did not share Pontiac's rage to rid the land of alien interlopers. He believed his people, whose ways he considered superior to those of the Europeans, could learn much from the white man.

When Brant next met with the Seneca chiefs they expressed disappointment that the Mohawk land grant was so far from their reserve in New York state and appealled to Brant to settle closer to them. They wanted to ensure Brant's leadership and guidance would be available if and when they required it. Once more Brant met with Haldimand and asked for another grant of land nearer to his Seneca brothers. Haldimand never hesitated and offered land near the Grand River "as soon as it could be acquired from the Mississaugas." Because John Deseronto preferred the more isolated Bay of Quinte settlement, Haldimand had to abandon his plan for a unified Iroquois community and agree to the establishment of two separate settlements.

It soon dawned on the British that the Grand River was a strategic site on which to settle the Six Nations. The Iroquois could serve as a barrier against American invasion from the west should hostilities with the new republic ever resume. At that location they could also act as agents of British policy in the disputed territories to the south and serve as intermediaries in the fur trade to the southwest.

Initially, the Mississauga Natives resisted the idea of accommodating former foes on their land until one chief, Pokquan, decided Natives would be better neighbours than European settlers. He was impressed with Brant and believed Brant's knowledge of the British could prove useful to his own people. Consequently, he persuaded the other sachems to agree to the sale. On behalf of the British government, John Butler negotiated with the principal "Chiefs of the Missasaga Nation" for the purchase of "the Spot of Land delineated on the Sketch" [See map.]

This 'spot' of land comprising about 800,000 hectares (2,000,000 acres) stretched from the source to the mouth of the river and six miles deep on each side of the Grand River.

|

|

Grand River Grant |

The grant was to replace land lost by the Six Nations Indians in New York State following the American Revolution. Butler said the Missasaugas consented to part with it "without any hesitation for which they received 1180 pounds paid to seal the bargain." At the time the "Missasaga Nation of Indians was an unsettled people numbering about six hundred men, women and children."

On May 22, 1784 the Mississauga assembled at Fort Niagara with British officials and Brant's Six Nations. Pokquan turned to Brant and said, "Brother Captain Brant, we are happy to hear that you intend to settle at the River Oswego (Grand River) with your people. We hope you will keep your young men in good Order, as we shall be in one Neighbourhood."

One of Haldimand's last official acts before returning to England was the proclamation of October 25, 1784 which made the deal official. "Whereas His Majesty having been pleased to direct that in Consideration of the early Attachment to His Cause manifested by the Mohawk Indians, & of the Loss of their Settlement they thereby sustained, I do hereby in His Majesty's name, authorize and permit the said Mohawk Nation and such other of the Six Nations as wish to settle in that Quarter to take Possession of & Settle upon the Banks of the River commonly called Ouse or Grand River. " Brant asked Haldimand to indemnify Mohawk losses which Brant said amounted to "near sixteen thousand pounds." Haldimand settled at fifteen hundred, that being as "near" as he felt the British government would approve.

|

|

Thayendanegea (Joseph Brant) Chief of the Six Nations by Wm Berczy, oil c.1807 |

According to the original Haldimand grant, a tract of approximately 833,333 hectares (2 million acres) from the source to the mouth of the river and 9.6 kilometres (6 miles) deep on each side. Later the government claimed that a mistake had been made in the original grant and that the northern portion hand never been purchased from the Mississaugas and could not, therefore, be granted by the king. Despite prolonged petitions by Brant and other chiefs, the promised property was never acquired.

Problems soon developed because Brant,an ardent advocate of Iroquois sovereignty, believed the grant of land was given on the same basis as land given to other Loyalists - in fee simple to do with as they wished including selling or leasing to private individuals. The land grant was too small for hunting, a lifestyle no longer viable since hunting was unproductive and traditional farming could no longer support the Iroquois, Brant negotiated numerous land sales to finance a transition to European-style farming. He believed his people could learn much about modern farming techniques if white settlers lived amongst them.

The sale of land brought Brant into conflict with government officials who believed land sales should be limited and the Crown should approve all transactions. Both Lord Dochester and Goveror John Graves Simcoe advanced the peculiar argument that the king's allies could not have the king's subjects as tenants!

An angry Brant protested to all and sundry about this restriction which he said was contrary to Haldimand's earlier assurances and promises of indisputable ownership when the Natives settled the land. Only later were they informed that they could not alienate (sell or lease) the land. Brant said this restriction made them only tenants unable to do otherwise with the land but "sitting down and walking on it." When Hunter banned further land sales or rentals by the Six Nations, Brant protested. "Should we be deprived of making the most of our landed property, many must Starve, many must go Naked." The official argument was that those who bought the land from the Natives might be "disaffected people who might injure Government," that is, conspiring Americans. Brant countered that "the people we have sold the land to are Loyalists" and were no different from those to whom Governor Simcoe himself had given land adjacent to the Aboriginal land. In fact, said Simcoe, land was being given by the Government to some of those "that had been engaged in war against us."

Contrary to the oft cited stereotype of Indians as defiant but doomed traditionalists, they were, in fact, noble but futile defenders of their ancient ways. Borderland Indians demonstrated remarkable adaptability and creativity in coping with the contending powers and with the growing numbers of invading settlers. Joseph Brant tried to manage rather than entirely to block the process of settlement. He did so in ways meant to preserve Indian autonomy and prosperity. Rather than sell lands for a song to governments, Brant and other sachems sought greater control and revenue by leasing lands directly to settler tenants. However, neither British nor American leaders could accept Aboriginals as landlords.

Brant rejected what he considered interference in Indian affairs and continued to lease and sell land. He eventually won the right to dispose of the land but his victory was a hollow one since it resulted in the loss of much of the original grant. By 1841 when the land was surrendered to the Crown to be established as a reserve, only a small portion of the original grant remained. The community today contains members of all six Iroquois groups and is known as the Six Nations of the Grand River.

The parcel of land currently contested in Caledonia is a remnant of the original grant given to the Six Nations. Where today hostility separates Native and non-native protesters, "history hints at happier possibilities for greater understanding and co-operation." Within a few kilometres of the site of the present standoff a different scenario unfolded 208 years ago in Brant's Village (now Brantford). Ancestors of both groups of today's protesters gathered for a feast at the invitation of Thayendenegea who led his guests in many toasts including one to "all those loyalists who were fellow sufferers with the Six Nations during the late American war." At Brant's festival it was possible to unite Native and none-native in a partnership that combined land development and justice to the land's original owners. It is to be hoped the spirit of Brant's benevolence will permeate the process that will see Aboriginal can e same congeniality will be possible

|

|

Lord Dorchester |

|

|

John Graves Simcoe |

Brant sought to forge the Six Nations and the western Indians into a great pan-tribal confederacy which could protect Native interests on the rapidly changing Anglo-American frontier. He presented his 'grand vision' to an Indian council of Wyandots, Delawares, Shawnees, Cherokees, Ojibwas, Ottawas and Mingos. "We, the Chief Warriors of the Six Nations with this belt bind your Hearts and Minds with ours. Let there be Peace or War, it shall never disunite us for our interests are alike."

|

|

Thayendanegea (Joseph Brant) Chief of the Six Nations |

Brant spent the rest of his life attempting to ensure the survival of the confederacy, however, it failed to function as he had hoped. The Americans simply ignored it and insisted on making treaties with individual tribes resulting in the loss of huge tracts of land. The diverse Indian nations never achieved unanimity and the confederacy fell by the wayside.

. |

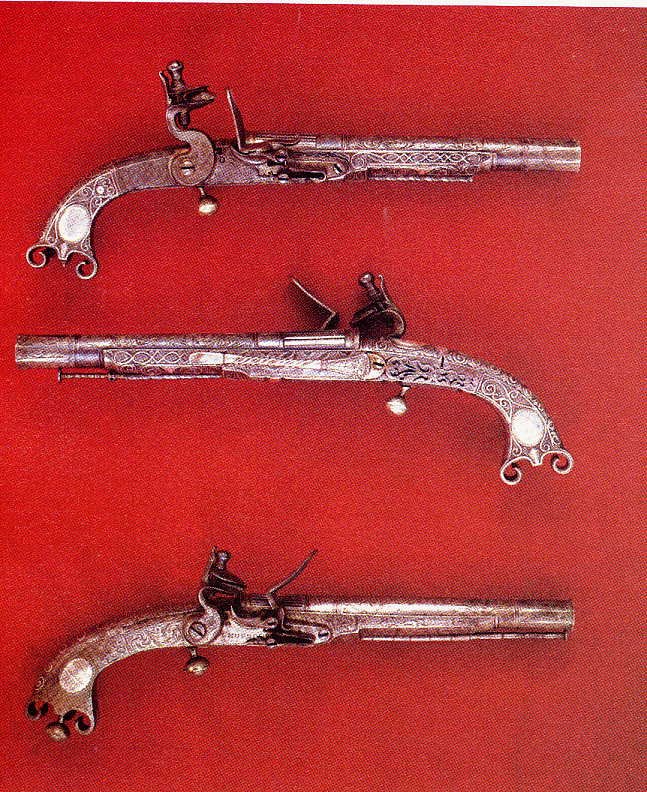

|

Flintlock Pistols Presented to Joseph Brant[****] |

Joseph Brant died in 1807. He was a noble figure who dedicated his life to advancement of his people. While he understood and accepted the European world as transplanted to America, he maintained his integrity as an Indian. "After all my experience and after every exertion to divest myself of prejudice, I am obliged to give my opinion in favour of my own people." As time passed and Brant foresaw the many changes that would occur the relationship between the First Nations and the whites. He warned that the Aboriginals,

In His Own Words

"must be convinced that change will not place them in a worse situation than they are in now. Change must occur in accordance with strict adherence to the dictates of Justice and rigid observance of all compacts and engagements on the part of the white people, including fixed boundaries and territories described." A convert to Christianity, he spent his later years translating the Book of Common Prayer and the Gospel of St. Mark into the Mohawk language.

|

|

Stately Brant Memorial At Brantford |

[*]This common spelling of Joseph Brant's Native name and the meaning given beside it is taken from the Dictionary of Canadian Biography

Brian M., a teacher of the Mohawk language, informed me that

In His Own Words

"This spelling is an old-fashioned one (but one still sometimes used in the community of Kenhteke - Tyendinaga) that uses 'd' instead of 't' and 'g' instead of 'k'. The 'ea' at the end of the name is an old-fashioned way of writing the nasalized vowel. Many of our traditional names that begin with 'te' often get shortened to just 't' as in this case. (A friend's name is Thohahoken -- 'he is between two roads' -- a shortened form of the grammatically proper Tehohahoken.) The proper spelling of Joseph Brant's native name is either Tehayentaneken or Tehaientaneken. All the speakers I know understand his name by the way it sounds, not by the way it is written. Its meaning is something like

'he has two (pieces of) wood side by side.'

His name breaks down as follows:

'te ...... aneken = two things side by side'

'..ha.............. = he'

'..... yent.......= wood'"

With regards to the meaning of Brant's native name as given in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography, Brian said, "As for two 'bets' side by side, I can't think of a way to say 'bet' as a noun, except as a long and clumsy made-up word -- tekahwihstayen'tshera -- which can not, according to our grammar -- be further incorporated in our naming conventions. The result, I suppose would be -- Tehatekahwihstayen'tsheraneken -- a non-word, non-name."

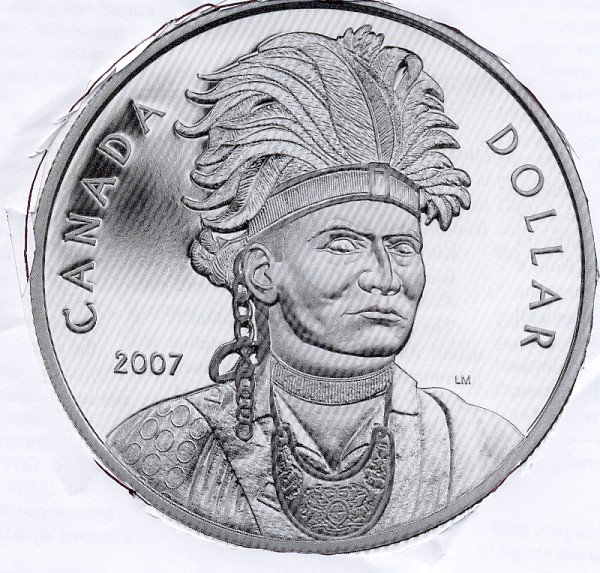

[**]Romney painted the 33 year old Brant in his London studio when Brant visited the city with Guy Johnson who was the royal commissioner of Indian affairs in America. Brant sat for Romney at his studio at least twice - on March 29th and April 4th. Brant is shown wearing a white ruffled shirt, an Indian blanket, a plumed headdress and carrying a tomahawk. Around his neck is a silver gorget, a gift from George III, which is now in the Joseph Brant Museum. Lord George Germain had a box of prints of the painting made and gave them to Brant as a gift. Today the painting is in the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa. [***] Mohawk rail blockade ends April 20, 2010 The constructiion of condominiums is planned in an area known as the Culbertson Land Tract which is on a section of land granted to the Six Nations by Haldimand in 1793. The Mohawks contend they never relinquished any part of it and a protest group led by Shaun Brant set up a barricade across the CNR railroad tracks in Deseronto to protest the slow pace of negotiations concerning this tract of land. Jim Prentice, the federal Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development, had warned the protesters to “abandon” their blockade because it could jeopardize ongoing negotiations concerning the land tract. The federal government has appointed a land-claims negotiator to try to resolve the long-running dispute, but Brant has complained talks have been moving too slowly. The protesters initially set up barricades at the gravel quarry operated by Thurlow Aggregates for a day in November and again in January. A third protest barricade went up last month and the group warned at the time that the demonstration might be expanded to the town of Deseronto itself. The barricade was removed after 24 hours to avoid violence but Brant threated other economic barricades if negotiations continue to drag on. The chief of the Tyendinaga band opposed the blockade and urged its removal. [****] Among the many gifts and presentations Joseph Brant received was this pair of flintlock pistols of the traditonal Scottish type. The pistols have steel rather than wooden stocks and are engraved and inlaid with silver. They were made originally for the Duke of Northumberland whose crests adorn the silver escutcheons on the butts. In 1791 the Duke presented the pistols to Joseph Brant and after his death they passed to his heirs and eventually came into the collection of the Royal Ontario Museum. [*****] The following article dated February 10, 2010 is taken from the Belleville newspaper, The Intelligencer. Belleville, a city in eastern Ontario, is just west of the Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory."The namesake of Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory and its nearby township has been honoured on a rare coin issued by the Royal Canadian Mint War hero Thayendanegea, whose Christian name was Joseph Brant, is on a commemorative silver dollar, the first collector coin issued in 2010. Brant’s achievements included rallying American tribes to fight alongside the Crown in the American War of Independence. He negotiated treaties and organized war efforts that have shaped what Canada is today, said Chief Don Maracle of the Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte (MBQ). If Britain hadn’t made allies with the Indians things would be very different today,"he said.

|

|

Coin Image 2010 |

Thayendanegea means "bind together to strengthen" or "he places two bets." Born in Ohio in 1741 Brant received an English education at Moor’s Charity School for Indians in Connecticut where he learned English and western literature. He became an Anglican missionary for Dr. John Stuart, the first legislative chaplain of Queen’s Park, and together they translated a prayer book and parts of the Bible into Mohawk. Brant's sister, Molly, married General Sir William Johnson, Britain’s superintendent of northern Indian affairs.

Brant became a Six Nations war chief and a British military captain. He earned the respect of both sides says a release from the Royal Canadian Mint. In 1783 following the War of Independence, he negotiated land for the Six Nations people in Ontario’s Grand River Valley. Brantford and Brant County are named after him. His former Burlington home located on the more than 3,000 acres of lands gifted to Brant for his allegiance is now a museum where the coin was unveiled last month.

The Brant honour is also an acknowledgment of Six Nations war efforts through generations which do not get enough recognition, Maracle said. There were heavy native contributions to the First and Second World Wars as well as contributions to the Korean War, the Gulf War and the current Afghanistan mission. They fought the revolution not as Loyalists, he said, but "nation-to-nation as loyal and faithful allies to the Crown."

"We have a history of over 300 years of military alliance with the Crown," he said. "The sacrifice of the Mohawk people was very significant. They lost their homes and arrived only with what they could fit into their canoes."

There are other Aboriginal war heroes such as Tecumseh who deserve to be commemorated, Maracle said.

There will be 65,000 of the coins distributed worldwide, said Alex Reeves, spokesman for the Royal Canadian Mint. The image is based on a portrait by Laurie McGaw. It retails for $42.95 and is available at select Canada Post outlets including the one in Foxboro.

Tyendinaga Township received its name in 1800 and is named after Brant, according to the Heritage Atlas of Hastings County.

[******]When the fighting ended Joseph Brant did not forget the whitemen who fought under him. When he was granted the Brant River settlement, he invited a number of whites to accompany him into the Grand River Valley. According to page 57 of the "Loyalist Families of the Grand River Branch UEL" published by Pro Familia Publishing, Copyright 1991, an article written by Mary Nelles "United Empire Loyalists Along the Grand River in Haldimand County" contains the following information."About half of the Six Nations Confederacy, with a majority of Mohawks, settled along the Grand River. There were some Delewares who made their homes south east of the present site of Cayuga. A few Mississaugas remained along the south west bank of the river in Oneida Township. Joseph Brant, who had been Captain of the Indian Department during the Revolutionary War, was the leader and spokesman for the Six Nations Indians. When he saw the vastness of the territory, he invited his comrades and friends who had served with him during the war and had lost their properties in the Mohawk valley, New York State to establish their homes in the Grand River Valley. The first to arrive was Lieutenant John Young who had served for seven years in the Indian Department. His father Adam Young, a private with Butler's Rangers, together with John's brother's Daniel, a sergeant and Henry, a private, made their homes on the shores of the river, southeast of York."

"In the following year Captain Heinrick Nelles who had served for eight years in the Indian Department, arrived at the river with his family. His oldest son Robert, who had served as Lieutenant in the Indian Department for four years, had a farm just south of York. Heinrick's farm abutted to the north. Their establishments were used for trading as well as farming. The Young and Nelles property was located in what later became Seneca township. Further south along the river Sergent Heinrick Huff and his son, private John Huff, both families in Brant's Volunteers, settled. John Huff married an Indian woman; in 1812 he returned to New York State. In what later became Canboro township, Lieutenant John Dochstader, of German ancestry, settled. He served with the Indian Department for seven years. He first married a Cayuga woman and they had a daughter; at the death of his first wife he married an Onondaga woman and they had another daughter. On 26 Feb 1787 a deed was issued to Heinrick Nelles, Robert Nelles, Warner Nelles, Adam Young, John Young, Daniel Young, Hendrick Young, John Dochstader, Hendrick Huff and John Huff."

"There is other information on the white Loyalists who accompanied Joseph Brant to the Grand River lands in this article as well. I received much of my information from the Oshweken Land Claims office while researching my Loyalists in the area. I have a copy of the Young family land deed but it is all in Mohawk. Other Loyalist who were given Brant Deeds are my Daniel Secord of Brantford (who married a Mohawk woman), Henry Windecker of Dunnville and many more that I am not positive about, most having been in the Indian Department or Brant's Volunteers."

Pat (Young) Kelderman UE "Loyalist Trails" [UELAC Newsletter 2010-21 May 27, 2010]>

This info taken from the Sault Star May 31, 2010 has not been uploaded yet. Negotiators set to make $125 million cash offer to settle CaledoniaJames Wallace/Osprey News Network

Ontario Life - Thursday, May 31, 2010 Updated @ 7:08:34 AM

Federal negotiators are poised to make a $125 million cash offer to settle the Caledonia land dispute with the Six Nations people, Osprey News has learned.

The offer is intended to resolve "historical grievances" between Six Nations and the government over land that community maintains was wrongly taken from them.

Ottawa has attached three principle conditions to the offer, documents obtained by Osprey News show.

First, the offer must be ratified by the people of Six Nations.

"We will require that there be a strong and significant consensus within the six Nations community for any settlement before it is finalized," the document states.

Federal negotiators are prepared to negotiate a "clear and transparent" ratification process but are looking for a consensus that reflects all points of view within the community, not necessarily unanimity.

The second condition attached to the cash offer is an assurance it will lead to a "full and final settlement" of the land claim.

That includes assurance the Government of Canada could not be sued in future over the claim and that the Six Nations would explicitly relinquish any claim to the lands in dispute.

Finally, the offer is contingent upon Six Nations members ending their occupation of the Douglas Creek Estates lands, a 40 hectare housing development near Hamilton, Ont.

Copyright © 2013 Website Administrator