Foreward | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

NEW FRANCE

"Man's urge has always been westward, face into the winds that ring the world. The history of modern North America is the record of this westward urge."

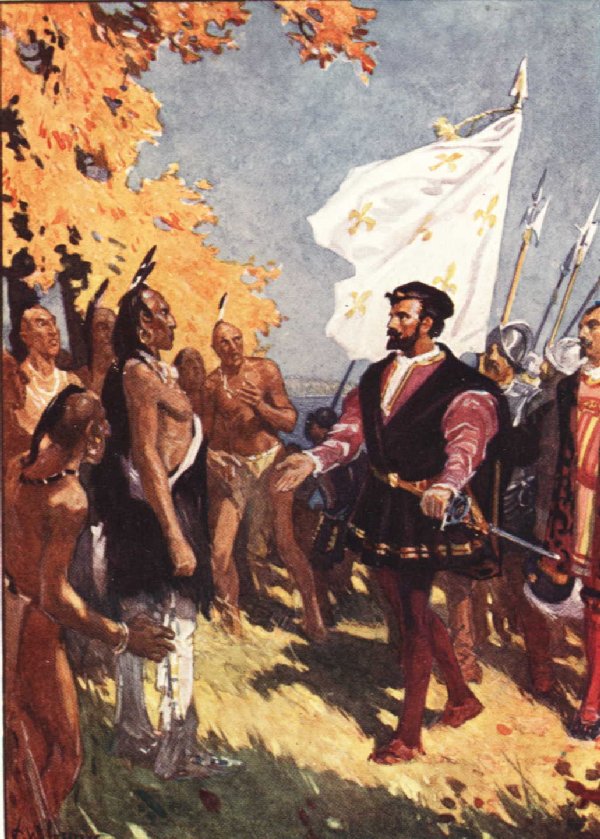

The French crown sponsored the voyages of Jacques Cartier (1534,1535-1536, 1541-1542) in an attempt to find the Spice Islands of Southeast Asia, but apart from establishing French claim to important parts of what is today Canada, these trips achieved little. The settlement fouded by Cartier and Roberval in 1541-1543 failed because they lacked economic foundation and because the Native population was hostile to them.

|

|

Jacques Cartier |

Jacques Cartier was well regarded by all seafaring men who knew him. At forty-three years of age, he was a stocky man with a sharply etched profile with calm eyes under a high, wide brow. He was slightly hawk-billed with a beard that bristled pugnaciously. He face, normally calm in contemplation of the sea, could be roused to rage and violent action easily. He was a capable, courageous man who was fair in his dealings. There was a hint of power in his steady, thoughtful eyes.

|

|

Jacques Cartier |

Jacques Cartier sailed from St. Malo, France in 1534 as a full-fledged navigator and captain in his quest for riches and a route to Asia, He was well aware that 'America' and 'Americans' had already been discovered. On April 20th the two little vessels departed, their commander, his stocky legs planted firmly on the upper deck, his dark eyes fixed ahead. He had set off to solve the enigma of the silent continent so far away to the west.

|

|

Jacques Cartier's Home In St. Malo |

Cartier's records of his three voyages are rich in detail about almost every aspect of the eastern North American environment and the people who inhabited it.

|

|

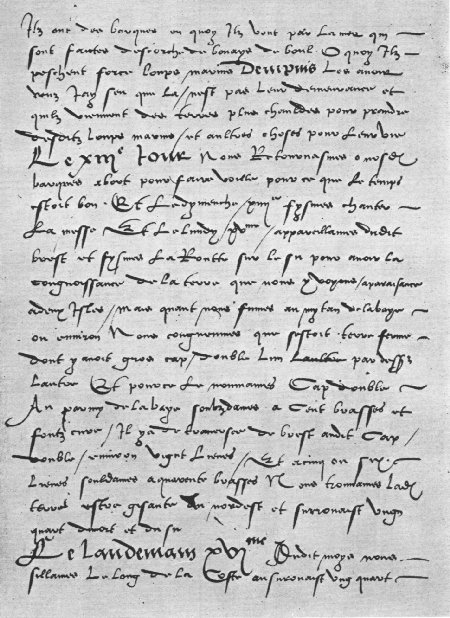

Page from Cartier's Diary |

He explored along the coast of Labrador and found "wild and savage folk" who covered themselves with certain tan colours" He explored along the coast of Newfoundland and rounded the northern tip and sailed through the Strait of Belle Isle an sailed into the Gulf. After crossing the gulf he came upon an island he named St.Jean (present day Prince Edward Island and reached the shore of what is now New Brunswick. Because the heat was intense, he called the bay in which they finally came to rest Chaleur; the Bay of Chaleur it has been ever since. When the Frenchmen finally left their ship to go ashore, they recorded that many eyes were watching them. Suddenly, canoes appeared as if by magic filled with lithe, lean, rugged, fearsome-looking men. Alarmed by the outlook, Cartier and his men turned their boats about and rowed back towards the safety of their ships.

The Natives paddled furiously and with speed that astonished the Frenchmen soon surrounded these strangely garbed newcomers. Their faces painted "hideously with red and white ocre," the Aboriginals signalled a desire to trade. Cartier "did not care to trust their signs" and fearing trouble he raised his arm as a pre-arranged signal and two of the little cannon on one ship were fired , their smoke and thunder scattering the painted people in all directions. They had not gone far, however, before curiosity overcame their fear and they turned about and once again approached the Frenchmen. This time Cartier ordered his men to raise their muskets and fire a volley into the air. This sharp salvo of "fire lances" - projectiles packed with "sulfur, cannon powder, powdered lead, broken glass and mercury," which shattered the air about their ears, shaking both their courage and their curiosity for they fled from the terrifying blast.

Cartier noted in his diary that they "would no more follow us." They did, however, for the next morning they reappeared with an obvious desire to trade. Cartier provided the first detailed description of the ceremonials surrounding trade when they returned on July 7th, "making signs to us that they had come to barter." Once during their conversation with Cartier, the Natives "burst out and made three cries together in full voice a sound horrible to hear." It was the war whoop which in days to come would curdle the blood of many in New France. Cartier had brought well-chosen trade goods: "knives and other iron goods and a red cap for their chief.". Before long the Natives were eagerly trading beautiful furs for tawdry trinkets from the first whitemen they had ever seen. The first day of the exchange was brief, the natives leaving stripped even of the furs on their backs.

The next day Cartier turned north again and came to another deep bay which Cartier hoped would lead to the illusive Cathay. Here on the mainland on Friday July 24th, 1534 he erectd an impressive monument, a cross some thirty feet high with a shield nailed to the crossbeam on which with a fleur-de-lis was carved: Vive le roi de France.

On the shore he had named, Gaspe, Cartier had founded an empire for France. |

|

Cartier and The Aboriginals |

Before long he realized that these North American people were not all alike: they spoke different languages, practised contrasting lifestyles and warred against each other. Cartier encountered Iroquoians cultivating land and controlling the country around present-day Montreal.

There are, it may be said, many kinds of voices in the world and none of them is without signification. Therefore, if I know not the meaning of the voice, I shall be unto him that speaketh a barbarian. And he that speaketh shall be a barbarian to me. 1st Corinthians 14, 10-11.

In May, 1535 Cartier set forth on his second and most important expedition to the new world, hoping to find the Great Lakes and the elusive route to China. With the help of Indian guides, he "he found the way to the mouth of the great river of Hochelega and the route toward Canada." On September 1 he reached the mouth of the Saguenay and anchored probably in the little bay where Tadoussac stands. As he sailed up the great St. Lawrence River the his first impression of this new continent was of its vastness and silence. It seemed at rest, in repose waiting the arrival of man to waken it to fertility. The forests along its shores were tall and dense, interminable and inscrutable. The only sounds issuing from the denseness the occasinal splash of a leaping fist and the distant cawing from the treetops.

Continuing on he arrived on the 8th at the Indian village of Stadacona in the shadow of the great rock of Quebec. "On the morrow the lord of Canada named Donnacona came to our ships accompanied by many Indians in twelve canoes." Later Cartier visited with Chief Donnacona at his village Stadacona (now Quebec City) lying at a point where the mighty river St. Lawrance narrows to the breadth of a mile. Cartier continued west hoping to discover the elusive China. He set out on the 19th of September and the journey to Hochelega took thirteen days. The glowing autumn colours fascinated the French who said they observed "the finest trees in the world" including maples, oaks, elms, pines, cedars and birches. Rapids in the St.Lawrence which Cartier named La Chine (China) prevented his journey by ship up the river, so he left it well guarded and continued in boats. Finally they reached open fields with a great mountain looming up behind. This highest point along that part of the St. Lawrence was called Hochelega (now Montreal) by the Natives. It was not the sought after city of the East.

Cartier and his men climbed the mountain and when they reached the top they beheld so impressive a panorama that Cartier gave the mountain the name Mount Royal.In all directions were mountains. He described the landscape that opened before them. "On reaching the summit we had a view of the land for more than thiry leagues round about. Towards the north there is a range of mountains running east and west. And another range to the south. Between these ranges there lies a great plain, the fairest land it is possible to see, being arable, level and flat. And in the midst of this flat region flowed the mighty river extending beyond the spot where we had left our longboats. There is the most violent rapid it is possible to see which we were unable to pass. As far as the eye can see, one sees the river, grand, broad and extensive which came from the southwest and flowed near three fine conical mountains which we estimated to be some fifteen leagues away." Cartier gazed at the silver ribbon stretching to the west until it was lost in the distance. The violent rapids were named by Cartier in mockery La Chine (China). The sight of them removed any last hopes of voyaging by boat directly to the great cities of China. Like Moses from Mount Nebo, Cartier stared westward to the promised land upon which he would never tread. Cartier could go no further. The Lachine Rapids flooding downward at a speed of thirty miles an hour and more barred passage by the ship's boats.

Cartier returned home on May 6th, 1536 and it was five years before King Francis I turned his attention once again to these new lands. The lure was now the Kingdom of Saguenay which it was fondly believed would rival the wealth of the Spanish empire. Cartier added materially to what was know about the new land. Not satisfied to sail up and down the Atlantic coast, he penetrated bodly into the St. Lawrence exploring it to Montreal.

Trade between Natives and Europeans took on new dimensions with the gradual development of the European market for furs, particularly beaver. It was by far the most important animal fur in Canadian history. The long barbs at the tip of each hair in the beaver's soft underpelt made it ideal for felt. The felt-making technique transformed animal fur into a soft, supple, water-resistant material. The supply of North American beaver stimulated European felt production and brought wide-brimmed hats into fashion. By the 1630s it was standard military dress and it had reached all classes of society. Fur became the second staple of the Canadian economy. The fur trade led to the exploration of the Great Lakes and contributed to the war between France and Britain.

|

|

Castor canadensis - North American Beaver |

The fur trade depended on the labour of Native peoples and on their centuries-old trading netwaork. Each hunting Native family used some thirty beaver annually for food and robes. After being worn for a year, the pelts that made up the robes shed their long, outer guard hairs, exposing the short hairs required for the pelting process. Several hundred thousand pelts, known as castor gras d'hiver were availabel annually in the St. Lawrence- great Lakes regions at the end of the sixteenth century. They were in great demand by Europeans.

Sixty-eight years later in 1603 the Founder of Canada, Samuel de Champlain, sailed up the St. Lawrence River and

|

|

Samuel de Champlain |

discoverd Algonkins occupying the same area. Iroquoians then controlled the peninsula of southern Ontario south and west of Lake Simcoe. Included in this linguistic group were some 16,000 Hurons (Wyandots) who were allied in origin and language to the Iroquois. To the southwest were the allies and kindred of the Hurons, the Tobacco or Petun Nation, their name resulting from the cultivation of large fields of tobacco, a commodity they used in widespread barter with other tribes. (Tobacco is still an important crop in their ancient lands.) Jacques Cartier was intrigued by the Huron's use of tobacco, which they smoked " in a hollow bit of stone or wood." The early pipe looked more like an enlarged cigarette holder, the bowl simply an enlargement of the stem with its opening in the front instead of on the top.

Cartier provided this description of the Huron's use of tobacco. "At frequent intervals they crumble up this plant into powder, which they place in one of the large openings of the hollow instrument and laying a live coal on top suck at the other end to such an extent that they fill their bodies so full of smoke that it streams out of their mouths and nostrils as from a chimney. They say it keeps them warm and in good health and never go about without these things. We made a trial of this smoke. When it is in one's mouth one would think one had taken powdered pepper it was so hot." This was probably the white man's first experiment with tobacco and it occurred some fifty years before Sir Walter Raleigh began to popularize smoking in Queen Elizabeth's London.

Southeast of the Petuns and west of Lake Ontario on both sides of the Niagara gorge was the Neutral Confederacy, the peaceful Atiwandaronks (People who speak a slightly differnt tongue). They were named the Neutrals by the French because they took no sides and refused to allow battles within their territory. They were friends alike of the Iroquois, the Algonkins and the Hurons. Champlain described them as a powerful people having "forty populous villages." He said the Neutrals were "the only nation living in total peace." They formed a confederacy or shifting alliance of tribes comprising five groups occupying from 28 to 40 villages lying south and east of Huronia. Confderation of tribes was common among Indians. Champlain said they lived "West of the lake of Entouhonoronons (Lake Ontario) and north of Lake Erie and extended across the Niagara River." East of the Neutrals and occupying the basins of the Genese and Mohawk Rivers was the dread confederacy of the Five Nations.

|

|

Iroquoian & Algonkin Nations |

Let us peer through the mists of time and examine the basic patterns of life which affected Indian thought and action. The confederacy of the Hurons (from the Old French Huron: a bristly, unkempt knave) consisted of four separate tribes: the Bear, the Cord, the Rock and the Deer, along with a few smaller communities that united with them at different periods for protection against the League of the Iroquois. The Hurons occupied a rich area of conifer and deciduous forests west of Lake Simcoe and east of Georgian Bay. In 1603 according to Champlain, almost all were centred on Georgian Bay and the area of Lake Simcoe. Jacques Cartier was the first European to meet them at the Huron villages at Stadacona (Quebec City) and Hochelaga (Montreal Island). The real name of the confederacy was Wendat (Islanders or Dwellers on a Peninsula) from which came the name Wyandot that was applied to the mixed remnants of both the Hurons and the Tobacco people. The strongest tribe was the Bear numbering about half the total population.

The Iroquoian tribes were sedentary, living in bark houses located within palisaded villages all joined by networks of trails. Near each fortified village there were fields of corn, beans, pumpkins and tobacco. For some Indians, particularly the Iroquois, agriculture became very important. They raised fifteen varieties of corn, sixty kinds of beans, eight and sorts of squash in addition to tobacco and other foods. The men cleared the fields, slashing an burning and the women did the actual planting in early spring. For corn the earth was hilled to help the roots take hod - a practice the early colonists learned from them. Several seeds, usually four, were planted in each hill: "one for the beetle; one for the crow; one for the cutworm and one to grow."

Only eight of the eighteen villages were fortified with palisades and ramparts. When danger threatened residents of the unfortified villages, they fled for refuge to the nearest fortified village or simply dispersed into the forest. A village usually contained no more than twenty or thirty dwellings, each of which accommodated from eight to twenty-four familes with an average of five or six persons per family.

Dwellings were separated by short distances to avoid complete destruction in event of fires which occurred frequently because of the open fires and the bark huts. Agricultural in habit, keen traders and in the main sedentary, these people made short hunting and fishing excursions and laid up stores for the winter. No settlement lasted longer than twelve to twenty years on account of the depletion of the fuel supply and the exhaustion of the unfertilized soil. Life was normally quiet and peaceful with few dissensions within a village, but tensions were more common between the different tribes. Around the villages and their cornfields there were dense woods inhabited by deer, bears and wolves. There were paths radiating throughout the forests to neighbouring villages and where rivers and streams existed they were crossed by wading or swimming.

|

|

Hurons In Aboriginal Dress |

The Hurons maintained a close friendship with the Algonkins to the north and east. While years before they had fought with their neighbours, the Tobacco people, by the time Champlain penetrated into southwestern Ontario they had cemented close relations with that nation. The only enemies of the Hurons were the Iroquois living south of the St. Lawrence River. The Hurons were not unique in this regard, since the Iroquois warred with any neigbours who refused to enter their League. The Neutrals lived squarely in the path of the Iroquois and for years they and the Hurons had steadfastly ignored every plea from the League of the Iroquois to fulfil their dream and join them in establishing the "Great Brotherhood."

Warfare took the form of raids and counter-raids during which no holds were barred. The Iroquois were without doubt the best warriors in the region. At first they struck in small raiding parties. These sporadic ambushes and retaliations seldom produced much change in tribal dominance byt they did provide warriors with their chief interst in life - proof of personal courage in combat. One French explorer described them thus: "They approach like foxes, fight like lions and disappear like birds." Offensive weapons used on both sides included clubs, stone axes and bows and arrows. Tomahawks did not appear prior to contact with Europeans. [See Below *] Some warriors used slat armour and wicker shields covered with rawhide to protect themselves from bone- or stone-pointed arrows, but these protective devices were abandoned once muzzle-loading guns appeared on the scene. Neither side had a really efficient military organization. There was no discipline to speak of since individual warriors could drop out of a conflict whenever they wished, incurring when they did so no other penalty than a little loss of public esteem. Defence like discipline was also loose. Some villages were protected by palisades, but most were not. Where no palisades existed, Natives under unexpected attack fled into the forest. Close contests between the two Confederacies might have continued indefinitely had the Iroquois not acquired more firearms and ammunition from the Dutch than the Hurons were able to obtain from the French fur traders along the lower St. Lawrence River.

|

|

Hurons and French attacking a palisaded Onondaga village |

The Tobacco people or Tionontati (There the mountain stands) and the Neutrals were hardly distinguishable from the Hurons in their customs. In 1640 the Neutrals had only nine villages while the Tobaacco had twenty-eight. Neutrals had little contact with the Europeans because the Hurons, fearful of losing their trade status as middlemen, never allowed passage through their territories to the French settlements in Quebec and the upper St. Lawrence was blocked by the Iroquois. In any case the Neutrals would have found it difficult on the St. Lawrence River route because they were not skilled in the use of canoes.

The League of the Iroquois, known by the neighbouring Algonkins as Real Adders, comprised five small tribes strung out along the hills of what is now western New York state. Know as the Five Nations, this later became the Six Nations when the Tuscarora, an Iroquoian tribe, was driven out of North Caroline and accepted into the confedercy about 1722, The map above indicates their approximate locations and boundaries around 1600 A.D. Each of the Five (later Six) had its own language, its own name and its own history, but collectively they call themselves Haudenosaunee,(People of the Long House).

In order from east to west they were:(a) Mohawk (Man Eaters) at the eastern door; they held "the place of flint."

(b) Oneida (A Rock set up and standing) They were "of the boulder."

(c) Onondaga (On the hill or mountain) They were the keeper of the flame.

(d) Cayuga (Where locusts were taken out) They were "of the marsh."

(e) Seneca (A distorted variant of Oneida, the two names having a common origin.) They were "the great hill people."

At no period in their history were the Iroquois a numerous people. Around the coming of the Europeans their total population excluding the Tuscarora was only about 16,000.[**] The largest tribe among the Iroquois was the Seneca totalling 7,000. The most aggressive, the Mohawks. totalled only 3,000 but they were always the fighting backbone of the Confederacy. Their sheer ferocity on the war-trail made them seeminly invincible in any numbers and of all the woodland tribes, they became the most dreaded adversaries.

|

|

Mohawk Warriors and French Missionary |

Flanking both ends of the confederacy meant the Mohawks and the Seneca tribes encountered their various enemies first and because of the confederacy's loose organizational structure, they often acted independently of all the other tribes. The Senecas were chiefly responsible for the destruction of the Huron, Tobacco and Neutral nations. The Mohawks took on the task of harassing the Algonkins, the Montagnais north of the St.Lawrence, the Abenaki and various other Algonkian tribes in the Maritime Provinces, New Hampshire and Maine. The three middle tribes contributed contingents for all major operations. Their numbers were: Cayuga: 2,000; Onondaga: 3,000; Oneida: 1,000. Because of their independent nature, problems sometimes arose when one tribe of the confederacy concluded a peace treaty with an opponent that was ignored or dismissed by the others. An example of this occurred in the seventeenth century when the French concluded a hard-won truce with the Mohawks only to find themselves suprised and dismayed to be assailed by parties of the Onondaga and Seneca tribes which did not recognize the Mohawk's moratorium on warfare with the whites.

|

|

Model of Long House |

The name Hotinnonsioni(Builders of Cabins) has been given to the Iroquois. These people were the most comfortably lodged in long houses. These contrasted with the small, circular wigwams of the Algonquian tribes usually housing only one family. Early whites saw long houses that were "fifty or sixty yards long by twelve wide with a passage ten or twelve feet long down the middle." number of fires they contained. Each fire added twenty or twenty-five feet to the length of a cabin and they did not exceed thirty or forty feet. A typical town might have fifty of such dwellings and one was said to have two hundred. The towns were surrounded by a ditch, rampart and stockade so strong, the English used to call them castles. Each rested on four posts for each fire which were the base and support of the entire structure. Around the entire cicumference, that is the two sides and the two gable ends, pickets were planted to secure pieces of elm bark wich formed the walls and which were bound together with strips made from the interior coating or inner bark of white wood. The roof framing is made with poles bent to form a bow which are covered with pieces of bark. These pieces overlap like slate.Inside the middle space is always the place of the fire from which the smoke escapes by an opening made directly above it in the roof which serves also to provide light since there are no windows. Movable pieces of bark are used to cover the hole during heavy rains.

|

|

Iroquoian Longhouse Based on Archeological Evidence |

Subsequent to 1603 Champlain travelled back and forth between France and Canada a number of times. During his travels up the St. Lawrence it became clear that conditions had indeed changed since the days of Jacques Cartier. The fierce tribesmen encountered by Cartier were mild-mannered men compared to the Natives south of the St. Lawrence who inspired fear and dread among all who knew of them. While Champlain did not immediately come into contact with this fiercesome force that lived in palisaded villages among the lakes of northern New York, he had numerous reports of their cruel, conquering ways. They were a people who brooked no opposition. They called themselves the Ongue Honwe, "the men surpassing all others."

On the nineteenth of June, 1609 several shallops manned by twelve men each bearing a short-barreled arquebus slung over his shoulder arrived at the broad, deep, beautiful mouth of the "river of the Iroquois" [the Richelieu]. The Richelieu was broad and bland. The Indians assured Champlain would sail up it to the Lake of the Iroquois. They were about to enter territory no white man had ever seen before. In the prow of the lead shallop was the intrepid, insatiably curious Samuel de Champlain peering intently at the shoreline, enrapturd by the unspoiled, primitive landscape whose woods came down to the shore. In the wake of the shallops were twenty-four canoes bearing sixty allies of the French, a war-party comprised of Native braves from the Montagnais, Algonkins and Huron confederacies. Champlain had promised to go with them on the warpath in return for which they promised "to take me to explore the Three Rivers as far as a place where there is such a large sea that they have never seen the end of it." Champlain was fulfilling his end of the bargain.

The lower stretches of the Richelieu River were easy going, winding among "many pretty islands which are low, covered with very beautiful woods and meadows." Animals, which were abundant and little disturbed by their presence since no one lived in this no-man's land, provided all the food they required. On reaching the roaring rapids at Chambly, Champlain found they were handicapped by the heavy shallops which could not be dragged through the rapids and were too big to portage among the large trees on shore. Champlain called for volunteers to accompany him further and two stepped forward. All the other quailed at the prospect of what was to come. "Their noses bled," said Champlain. After ordering the remaining Frenchmen to return to their settlement at Quebec, Champlain and his two companions set off with the Indians in their light, bark canoes which could float in a few inches of water and be carried by one man easily over the winding wilderness trails. There were twenty-four canoes with sixty Indians, a mingling of Hurons, Montagnais and Ottawa Algonquins. The Frenchmen carried all their baggage as well as their heavy arquebuses, powder, match and shot. The wore steel armour, half armour.

|

|

Building A Bark Canoe |

Champlain recorded the following in his journal. "I set out then from the rapid of the river of the Iroquois on the second of July. The Indians took their shields, bows, arrows, clubs, swords fixed to the ends of long sticks and their canoes and carried them about half a league by land to avoid the swiftness and force of the rapid. They made their way so fast that we soon lost sight of them. This displeased us but we followed their tracks but often went astray and would not have known where we were had we not caught sight of two Indians moving through the bush. We called out to them and they agreed to guide us. The others were travelling quickly on ahead. After rowing 120 kilometres we entered the largest body of inland water they had ever seen, a lake which Champlain named after himself.

On the evening of July 29th we sighted off the point while later was to be the site of Fort Ticonderoga, a number of canoes that the our Indians immediately noted were heavy in the water, a fact indicting they were made of elm bark - the tree of choice of the Iroquois. Hardly had we gone an eighth of a league further before we heard the howls and shouts of both parties flinging insults at one another and with scattered skirmishing whilst waiting for our arrival. As soon as our Indians saw us, they began to shout so loudly that one could hardly have heard thunder."

|

|

Champlain at Lake Champlain |

Contrary to the established practice of Indian warfare, the two parties approached each other openly and challenges to battle were hurled in jeering voices across the tranquil water. Two Iroquois canoes paddled out for a parley to learn from their enemies whether they wised to fight and these replied they had no other desire. The Iroquois were too well trained in forest fighting to risk conflict on the water. Since it was dark and they could not distinguish one anothe, they said as soon as the sun rose, they would attack us. This was the etiquette of war; a parley and an agreement on the hour of battle. Once this was completed, the Iroquois returned to the shore from where they hurled taunts of their enemies' feebleness and foretold how they would be eterminated by the prowess of the Iroquois warriors. Champlain's allies yelled back that the Iroquois were going to experience a power of arms such as they had never seen before.

The Iroquois then disappeared into the forest, where throughout the night they danced to the flickering light of their fires, singing all the while their war songs in high, shrill voices, songs of insult and songs of celebration of their coming triumph. They had no doubts whatsoever that victory would be theirs. Champlain's companions returning jeer for jeer spent the night in their lashed-together canoes. Champlain wondered at their resolve in the face of such fearsome odds for the Iroquois appeared to outnumber them four to one. Was their seeming bravado simply a case of whistling in the dark? It was hard to remain confident in the face of the awesome uproar coming from the Iroquois camp.

Morning found the Frenchmen donning their breastplates, the highly polished metal reflecting the rays of the rising sun. Then lying hidden on the bottom of the canoes, the Indians paddled to shore unhindered by the Iroquois and formed in battle aray. With carbines loaded and sword and dagger dangling from their waists, Champlain and his companions advance warily, their fingers steady as they awaited the onslaught. Finally the Iroquois warriors appeared, marching solemnly into battle with taunting laughter, "strong and robust to look at, coming slowly toward us with a dignity and assurance that pleased me very much."They numbered about 200, strong, robust men led by three plumed chiefs. The allies said I should do all I could to kill them.

Champlain was most impressed with his foes' physical magnificence. Tall, lithe, splendidly muscled, they were a superior looking enemy. Three chiefs, their heads topped with snowy plumes, strode ahead, their hysterical howling and fierce demeanour frightening to behold. The French allies parted and Champlain moved foreward slowly through the opening. Seeing a whiteman for the very first time, the Ongue Honwe fell silent, their fierce eyes filled with a sense of wonder and awe. Surely, this was a white god. With no sign of haste, his arm and aim steady, Champlain pointed the arquebus loaded with four bullets directly at the three chiefs and pulled the trigger. His eye and aim were excellent for the explosive charge felled all three of the chiefs, killing two of them instantly and the third after a short period.

The sudden explosion followed immediately by three fallen chieftians jarred the senses of the Iroquois. However, it also released them from their transfixed spell. In the face of the thunder and lightning of this awful god, they realized they had to fight or die and they loosed a barrage of arrows at their enemies. At this critical moment the other two Frenchmen stepped forward from the side and fired point-blank into the aroused Iroquois. More gods and more roaring thunder were just too much. Te Iroquois were proud warriors but the sight of all that flash and smoke coupled with the sound of the explosions, the terrified warriors turned and made for the woods, fleeing for the first time ever in the face of their hated enemies. Their harried howling and panicked flight brought the allies to life and with hatchets and scalping knives brandished, they sprang forward in pursuit of their fleeing foe.

|

|

Champlain's Musket Blast |

Champlain's first musket blast ensured French-Iroquois conflict for years to come. Espousing the cause of the Montagnais, Algonkins and Hurons against the Iroquois was to have bloody repercussions. Champlain's participation in 1609 with his allies in their successful assault against a Mohawk war party on Lake Champlain resulted in a bitter feud between the French and the Iroquois confederacy. The people of the Long House never forgot nor forgave and nursed a hatred for the French that the years did not diminish nor the spilling of blood ever sate. Even after the Hurons had been exterminated and the Montagnais ceased to count, the feud festered. The Iroquois's smouldering wrath vented itself in furious raids on the settlements of New France. In 1664 Louis XIV gave orders to "totally exterminate" the Five Nations, but the best the French could do was burn their castles and their cornfields.

The feud blocked French extension southward and made the Iroquois staunch allies of the English, an alliance lasting down to the capture of Quebec by General James Wolfe in 1759. No other policy seems to have been open to Champlain whose actions were the result of a carefully considered policy. Colonization would only be possible if the fur trade flouished enough to retain the financial backing of business associates in France. This required the efforts of the Montagnais and the Algonkins whose long flotillas full of furs floated down the Ottawa to trade at Hochelaga. In order to maintain this source of fine furs, Champlain had to support his natural allies in their never-ending conflict with the Iroquois. If he wanted their furs, he had to fight beside them. The Iroquois had no great regard for the English either, but when the two nations were at daggers drawn, as was often the case, the Six Nations always allied themselves to the English.

|

|

Champlain's Travels |

In July 1615 Champlain ascended the Ottawa River, crossed Lake Nipissing and descended the French River to Georgian Bay where he visited the Huron Villages. In August he set out with a war party of Hurons to attack the Iroquois. Their route was by way of Lake Simcoe, the Trent River, the Bay of Quinte and across the foot of Lake Ontario from where they entered Iroquois country. The expedition proved to be a failure with Champlain being wounded and the Hurons routed. However, because the Mohawk's occupied the most vulnerable position on the eastern flank of the confederacy, they suffered heavily from their inferiority of weapons and were almost annihilated by the Algonkins in the latter half of the sixteenth century. This changed around 1615 when the Iroquois begab ti acquire arms from the Dutch settling in Pennsylvania. This turned the tide in favour of the Mohawks and they gradually extended their sway over all the territory from Tennessee to the Ottawa River and from the Kennebec River in Maine to the southern shore of Lake Michigan.

The Europeans brought more than guns and other goods with them when they landed on North American soil. More potent by far than muskets were the microbes, teeming invisible immigrants in the form of smallpox, diphtheria, influenza, cholera, measles and the like. These invincible stormtroops decimated the Native peoples who had no immunity. Th epidemics spawned by the continuous contact with the French were devastating, the mortality rates resulting in the death of half their population lost in the span of 30 years or so. This was also a period of extreme hardship when the Iroquois contemptuously labelled them with the epithet "dog-eaters."[***]

It was during this period when the Hurons were weakened by smallpox and other diseases, that the League of the Iroquois decided to launch a determined attack on Huron settlements. The forces to the north still outnumbered them and they felt this was the time to act. Their scouts had revealled that the Hurons were weak tactically since they failed to maintain a strong fighting force in any single strategic point. The Iroquois chose this time to attack for several reasons: they were convinced that the Iroquois unity had to be established or its opponents destroyed; they recognized that trade was becoming all-important and resented the Huron's dominence in this regard. Since their own lands did not produce enough furs, the feared other nations would soon outstrip them in wealth and firepower. In 1648 they were ready to strike. They sent out word that all tribes not allied with the League must consider the consequences. By the time the astounded Hurons received this word, the Iroquois were upon them. In a single year the great Huron Nation had ceased to exist. They destroyed the Tobacco nation as well for harbouring Hurons who had fled to their lands when they were attacked by the Hurons. Because the Iroquois were always quick to avenge a real or imagined insult, the Neutrals suffered the same fate. The Senecas attacked their villages because Neutrals had allowed a Seneca brave to be captured by the Petun in Neutral territory. It was charged, too, that the Neutrals, were in violation of their neutrality because they were holding large numbers of Huron refugees as prisoners. The few from both confederacies who survived the onslaught were absorbed by the Senecas. Instead of returning to their homes as they normally did following a fight, they past the winter in southeastern Ontario and in early spring renewed their surprise attacks. Many of the Hurons were killed or carried wawy into captivity. Those remaining fled in all directions to the Tobacco, the Neutrals and the French. These unrelenting raids scattered the Hurons far and wide, many fleeing and more being voluntarily absorbed by the Iroquois.

|

|

Huron Survivors Assisted by the French |

Initially, Governor General Sir Frederick Haldimand, the aloof Swiss professional soldier, believed that the Western country should be reserved for the Aborigines, whose loyalty to Britain had been sorely tried by reports of the peace treaty with the United States which left their traditional hunting grounds within the new republic. When he learned that the Natives of the area would not consider the Loyalists unwelcome invaders, he directed Holland on May 26th, 1783, to "proceed to Cataraqui [Kingston] where you will examine into the situation." Haldimand settled a number of Loyalist groups along the upper St. Lawrence, where he granted them land and supplies. He also instructed Holland to send his assistants to the Niagara country to assess its suitability for settlement.

Holland's subsequent reports greatly impressed Haldimand with the quality of land. Although some of it was "broken land," by which he meant rocky because of the Precambrian Shield which stretched down across the St. Lawrence River, most of it was so fair that, In His Own Words

"I think the Loyalists may be the happiest people in America by settling this country."

These positive reports led to plans for the launching of pioneer land surveys of the upper country. The British practice was to forbid private purchases of land from the Aborigines, and instead negotiate formal treaties with the Natives, who regarded themselves as allies, not subjects, of the British king. The government alone gave legal title to Aboriginal lands. This policy was the basis of peaceful relations between England and Canada with the Native nations, unlike the nearby American states, where American troops clashed repeatedly with the tribes of the Ohio valley. Upper Canada never had a fiery Native frontier.

|

Acting on behalf of the Crown in October, 1783, William Redford Crawford of the Royal Regiment of New York purchased from the Mississaugas [People of the large river mouth] who were located on Carleton Island, land for settlement which eventually became the counties of Frontenac, Prince Edward, Lennox and Addington, Hastings, Glengarry, Stormont, Dundas and Leeds. At Niagara on May 22nd, 1784, Major John Butler completed negotiations with the Mississaugas for the purchase of an extensive "tract of country" for settlement situated between Lakes Ontario, Erie and Huron. For the sum of 1180 pounds, 7 shillings and 4 pence, the said "Wabakanyne, Sachems, War Chiefs and Principal Women in band, will and truly did grant, bargain, sell, alien, release and confirm unto His Majesty, all that tract or parcel of land lying between the Lakes Ontario and Erie." The purchase of this land by Indian treaty made possible the western spread of the settlement of Niagara.

|

Negotiations for land did not always conclude cordially, and in this instance there appeared to be some dispute over the accuracy of the boundary of this purchase. In a letter written by John Graves Simcoe in March of 1792, Simcoe indicated there were "doubts relative to the Boundary" of this land purchase from the "Messessaga Indians," and he requested that Samuel Holland determine whether "a North West Course drawn from the Waghquatata Lake, does or does not strike the River La Tranche or New River."

It also appears that presents promised to the Native peoples for their land did not always reach them. In September 1793, Simcoe reported to his superior that "the Messissagua Indians, who are the original proprietors of the land which as been sold to the Government, make great complaints of not having received the presents which they stipulated when they sold the lands. Colonel Butler upon my enquiry told me this originated from a mistake of Sir John Johnson's who had given the presents to the wrong persons."

|

In January, 1794, Lord Dorchester informed Simcoe that a plan for another land purchase had been found in the Surveyor General's Office which contained a blank deed along "with the names or totems of three Chiefs of the Mississaga Nation" attached thereto. The totem mark of the Mississaga was an eagle, however, since the deed was blank, it had no validity and Dorchester said it would be necessary for the British government "to purchase it anew." [* See below]

In November 1795, on behalf of the British government, John Butler negotiated with the principal "Chiefs of the Missasaga Nation" for the purchase of "the Spot of Land delineated on the Sketch" This was some 'spot' of land. It was six miles deep from each side of the Grand River, beginning at Lake Erie and extending to the head of the river. This land was to replace land lost by the Six Nations Indians in what became New York State following the American Revolution. Butler said the Missasagas consented to part with it "without any hesitation" for which they received "1180 pounds paid to seal the bargain." It was reported that the "Missasaga Nation of Indians was an unsettled people numbering about six hundred men, women and children."

Large scale surveying of the land purchases was begun by the Deputy Surveyor General, John Collins, who was directed by Haldimand to proceed "to Cataraqui in order to survey and mark out the settlement at that place for the refugee Loyalists" for whom farm lots were urgently needed. "Excessive bad weather" waterlogged the countryside and delayed the commencement of work until late October, 1783. What was the surveyor's task? "It was to measure the natural features of the earth and its waters, to scan the heavens, to locate and fix the boundaries of areas into which man has decided to divide the planet and to determine precise dimensions, directions and relative positions. His work meets the urgent need of man to see his locality, his nation and the world as a whole and in relation, one to the other; to orient himself and his interests within the earthly and heavenly environment."

Townships were laid out and divided into concessions which were divided into lots. To ensure fairness in the distribution of the land, Haldimand directed that the lots be awarded "impartially by drawing for them." He insisted this was to apply equally to the officers as well the lesser ranks, a decision which was not popular with the former.

The physical and man-made conditions under which surveyors laboured were harsh and often difficult. In addition to working in"excessive bad weather" while being eaten alive by "insects in such multitudes," Lieutenant Governor Simcoe established tough working conditions for them. In 1792 Simcoe directed that one quarter of a dollar a day be allowed to the surveyor "to find your own ration." For a "coasting survey" any number of men up to ten could be employed; for an "inland survey," not more than 12 could be employed. The allowance for axemen was 1/6 of a shilling a day and for chainbearers 2 ½ shillings a day. For the quarter dollar a day he received, the deputy surveyor was obliged to provide for each person in his party: 1 ½ pounds of flour, 12 ounces of pork and ½ pint of pease (peas). If he was "furnished with a Battoe, (bateau) axes, tomahawks, camp kettles, oilcloths, Tents, Bags from the King's stores, you will be allowed only 10 pence rations for your party."

|

The practice at the time was for the surveyor to set up his circumferentor on a level stump or a flat rock and take a sight along the intended township baseline. Axemen cut away obstructing trees. One chainman carried and opened up the remaining 99 links of the chain to a point determined to be precisely correct, the surveyor then signalling the picketman to drive in a stake at that point. At the termination of every fourth lot, a span of one chain was provided for a future side-road. If he came to a creek or swamp the surveyor recorded that feature in his field book. He also entered details regarding the quality of the soil, number of rock outcroppings and types of timber.

|

Land grants were sought by Loyalists and other settlers as a natural right, and by lobbying and intense labour they often acquired large holdings. Land was allotted in a variety of ways and over time, confusion resulted regarding who owned what and where it was located. In order to ensure that property and its rightful owners were dutifully documented, registry offices were established in the various counties. The bicentennial of their establishment was 1997.Settlement in the province began in 1784 when land was granted by the "bounty of His Majesty" to Loyalists and disbanded troops who had joined the Royal Standard during the American War. Initially land grants were made by commanding officers of the various posts under authority of the Commander in Chief.

Surveyors normally surveyed the land into 100-acre parcels, but exchanges of lots based on personal preferences permitted the acquisition of larger holdings in a particular location. Mining rights on the land were excluded, for titles were granted solely for the purpose of agriculture. The Crown retained mining rights on all properties. To be granted a lot one had to be a professing Christian, physically capable of clearing, cultivating and improving the property, and able to provide proof of having obeyed laws and led a life of inoffensive manners in one's former country.

|

Candidates also had to subscribe to the Oath of Allegiance and the following Declaration: "I, John Doe, do promise and declare that I will maintain and defend to the utmost of my power the authority of the King in his Parliament, as the Supreme Legislature of this Province." Settlers who refused or neglected to comply with the declaration were "turned off" their property forthwith.

|

One petitioner named David Palmer submitted the following petition to Lieutenant-Governor John Graves Simcoe on July 5th, 1795.

In His Own Words "To His Excellency John Graves Simcoe, Esquire, Governor and Commander in Chief in and over His Majesty's Province of Upper Canada.

The Petition of David Palmer

Humbly sheweth:

"That your Petitioner was an Inhabitant of Sussex County, State of New Jersey, and for many Years followed the business of a Miller by which he supported himself and Family in a Reputable way and was situated in a part of the said state where the Refugees and other Loyalists that had fled to the British standard. Resorted in a Private manner by means of which he had it in his power to Give them succour, which he did in the best manner he could and also gave great assistance in getting their Recruits to the Army, whereby he became suspected by the then Ruling Power and suffer'd much in his property by the Severe and Inhuman Laws passed in the said State against Loyalists, whereby he became little better that a Bankrupt and that in the year 1788 he came to this Province with his Wife and Children, several of whom are now become Inhabitants. Therefore, your petitioner prays that your Excellency will Grant him such an allotment of Land as you in your wisdom may think he merits and your Petitioner as in duty bound will ever pray.

40 Mile Creek, July 5th, 1795"

Land was distributed by lot with each pioneer receiving a certificate signed by the Governor and counter-signed by the Surveyor General or his deputy. It declared that John/Jane Doe, entitled by His Majesty's grace to a quantity of land, had drawn Lot Number 'x' in a certain concession of a certain township. Having settled thereon and improved his location, the grantee at the expiration of 12 months was supposed to receive a Deed of Concession, which permitted the owner to alienate (transfer) or devise (bequeath) the property. Land Boards were introduced in the various districts in 1789. The five-year period during which they existed extended over the important pioneer growth period when townships along the upper St. Lawrence, around the Bay of Quinte, along the north shore of Lake Ontario and the west bank of the Niagara River were settled.

|

|

Dark Sections Indicate Areas of Early Settlement |

An important part of the Board's function was to control the extensive growth of land speculation which made its appearance at a very early date. Much of the speculation resulted from individuals from the United States who applied for land to sell, not to settle. Newly granted land not actually settled within a year was forfeited, and land could be transferred only with Board approval. Persons not intending to become active settlers were refused applications, and entries of ownership often had to be cancelled for non-settlement. Boards also confirmed property locations previously made and granted lands by certificate. When the Boards ceased to exist on November 6, 1794, magistrates of the different districts handled allotments of land up to two hundred acres. The Executive Council dealt with petitions for larger grants of land.

Despite attempts to document ownership, the sole proof of title was often the fading script on the yellowing scrap of paper originally issued. For ten years after the first land allotments were made, scarcely a single grant had been ratified and by then many settlers were reluctant to exchange their jealously guarded yellowing piece of paper for an official document.

During its fourth session in August, 1795, Upper Canada's first parliament ratified the Registry Bill. It was considered so important by the Members and those they represented that it was passed quickly with only a minor amendment made to its preamble. This first of our Registry Acts established a registry office for each county and paved the way for the general issue of patents by providing for the registration of all deeds, mortgages, wills and transfers. In order that "deeds to perfect titles" could be granted, it was proclaimed on August 21st, 1795, that lawful land claimants must make known their claims to the attorney general within six months by the production of tickets, certificates or "such other testimonials," so that grants could be issued under the Great Seal of the province. Land owners were warned that failure to submit such documentation could result in the lands being "deemed vacant and granted to other applicants."

The existence of private property made survey markers or monuments critically important, and "cursed be he that removeth his neighbour's landmark." Upper Canadians did not take kindly to willful interference with their boundary markers and few places in the world had penalties as severe for removing or damaging them. During the first session of parliament held in York in 1798, the Legislature enacted a statute which stated: "If any person or persons shall knowingly and willfully pull down, alter, deface or remove any such monument as aforesaid, he, she, or they shall be adjudged guilty of felony, and shall suffer death without benefit of clergy," the latter phrase signifying punishment of utmost severity. Over the years the sentence was softened. It became a misdemeanor in 1849 and today the maximum sentence for disturbing a boundary monument is imprisonment for five years.

Toronto Built on Bargain Land [*]

"Pittance paid for 100,000 hectares. At the very least it could be described as the mother of all bargains. At the most, a case of grand theft land. For 10 shillings - then roughly the daily earnings of a low-ranking foot soldier in the British army - the government of the day bought up the land that is now Toronto. Now, nearly 200 years after the 1805 sale that saw more than 100,000 hectares of land change hands, the government of today and the Mississaugas of the New Credit First Nation are poised to hammer out a better deal - one that has the potential to be one of the largest land claim compensation settlements of its kind."On Tuesday representatives of the federal government and the Mississaugas will hold a joint press conference in Toronto to bring the public up to speed on the history of the so-called "Toronto Purchase" land claim, and where it is headed. The two sides, says Chief Dan LaForme, are about to begin negotiations in earnest{In 1805, the last time they sat down together to seriously negotiate, a revised deal was reached - one that attempted to remedy a previous, flawed deal, made in 1787. The earlier treaty resulted from a meeting between one of the King's men and the Mississaugas at the head of the Bay of Quinte, and purportedly ended with the Mississaugas surrendering all lands north of Lake Ontario. The deed, however, was unsigned, and that was a problem.

"Years later, in 1805, a government representative approached the chief of the Mississaugas (those involved in the first deal were dead) with a fresh proposal. This time, the land was surrendered for 10 shillings. The surrendered land stretches over 20 kilometres from Etobicoke Creek in the west, to Ashbridge's Bay in the east, and extends inland more than 40 kilometres. The Toronto Islands were not part of the first deal. Somehow, they ended up on the second surrender deal, according to the Indian Claims Commission's Web site, and the First Nation never accepted the boundaries as spelled out in the 1805 treaty. The band says the islands were not part of either deal, and both are being disputed.

"In all, the land in question covers 100,312 hectares. The Mississaugas say the land was never properly surrendered. The Mississaugas' claim is one of many, similar ongoing claims across the country. Many have ended up in court, tangled in lawsuits. That has not happened in this case. And that is how Chief LaForme would like to keep it. "The government of Canada has been willing to sit down and proceed with negotiations, so that tells us that they're willing to come to some kind of agreement with us, rather than taking the court route." LaForme said he has no idea how much a settlement in this case might be worth to the 1,500 Mississaugas who live both on and off the reserve land. The Mississaugas settled a claim on an 81-hectare parcel of land in 1997 for $12 million."

[*] Jacques Cartier usued the word tomahawk for hatchet, but did not state that it was used in combat. A century later another European speaks of the Mohawk using "weapons of war such as bows and arrows, stone axes and clap hammers." [**] The source of this figure is "Indians of Canada" written in 1960 by Diamond Jenness, a highly esteemed expert on Indians of Canada, for the National Museum of Canada. Another source, Stolen Continents, written in 1992 by Ronald Wright, states that there might have been "several hundred thousand before the great pandemic of the 1520 and maybe only 75,000 a century later." [***] Archeological digs near Penetanguishene revealled during this period only small amounts of corn and a high percentage of dog bone and evidence that the people were eating bark, leather blankets and anything else organic. There were also signs of plague expidemic and much ceremony in attempts, no doubt, to bring on better times.Copyright © 2005 W. R. Wilson