Foreward | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

INDIAN AFFAIRS

History reveals pieces of the puzzle.

NEW FRANCE

"Man's urge has always been westward, face into the winds that ring the world. The history of modern North America is the record of this westward urge."

|

|

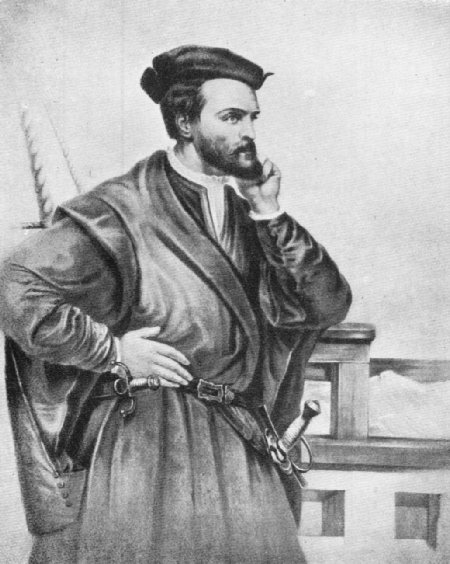

Jacques Cartier |

Jacques Cartier, a full-fledged navigator and captain, was held in high regard by seafaring men who knew him for he was capable, couragous and fair in all his dealings. Now forty-three years old, he was a stocky man with a sharply etched profile. His eyes, while calm, steady and thoughtful under a high, wide brow, held a hint of power. He was slightly hawk-billed with a beard that bristled pugnaciously. His face, normally calm in contemplation of the sea, was easily roused to rage and violent action. From St. Malo, an old harbour steeped in the seafaring tradition, two vessels set sail on April 20, 1534, their commander's stocky legs planted firmly on the upper deck, his dark eyes fixed ahead. Cartier was well aware that 'America' and 'Americans' had already been discovered. He sailed to solve the enigma of the silent continent so far away to the west and to seek riches. His actual commission has never been found but An order from the king in March stated the objective of the voyage: "to discover certain islands and lands wereh it is said that a great quantity of gold and other precious things are to be found." A second objective was to find the route to Asia.

|

|

Jacques Cartier |

|

|

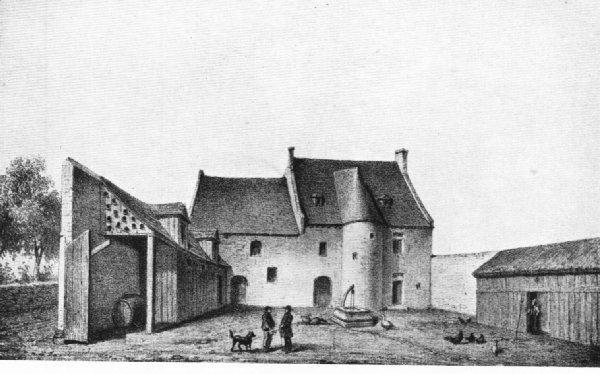

Jacques Cartier's Home In St. Malo |

Cartier's records of the three voyages he eventually took are rich in detail about almost every aspect of the eastern North American environment and the people who inhabited it.

|

|

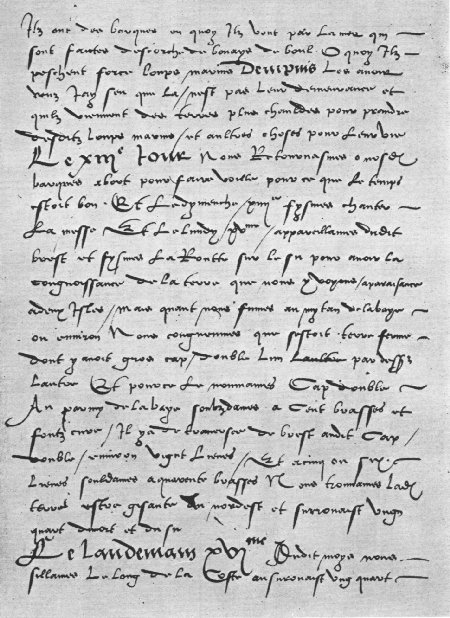

Page from Cartier's Diary |

He explored along the coast of Labrador where he found "wild and savage folk" who covered themselves with certain tan colours" He explored along the coast of Newfoundland then rounded the northern tip, sailed through the Strait of Belle Isle and south-west along the shore into the Gulf of St. Lawrence. The wind blew cold and hard from the northeast. The weather like the days was dark and gloomy and through the rifts of the mist and fog on the face of the water the coast appeared formiddable and scarcely habitable. After crossing the gulf he came upon an island he named St.Jean (Prince Edward Island).Turning toward the northwest the ships followed the outline of the coast seeing "the fairest land that may possilby be seen full of goodly meadows and trees." They reached the shore of what is now New Brunswick. Because the heat was so intense in the bay in which they finally came to rest, he named it Chaleur and the Bay of Chaleur it has been ever since.

When the Frenchmen finally left their ship to go ashore, they recorded that many eyes were watching them. Suddenly, canoes appeared as if by magic filled with lithe, lean, rugged, fearsome-looking men, their faces "hideously with red and white ocre," Alarmed by the outlook, Cartier and his men turned their boats about and rowed back towards the safety of their ships. The Natives paddled furiously and with speed that astonished the Frenchmen soon surrounded these strangely garbed newcomers. The Aboriginals, making a great noise and geticulating wildly, signalled a willingness to trade but Cartier "did not care to trust their signs." Fearing trouble, he raised his arm in a pre-arranged signal and a salvos were fired from two little cannons. their smoke and thunder scattering the painted people in all directions. They had not gone far, however, before curiosity overcame their fear and they turned about and once again approached the Frenchmen. This time Cartier ordered his men to raise their muskets and fire a volley into the air. The sharp sound of the "fire lances" - projectiles packed with "sulfur, cannon powder, powdered lead, broken glass and mercury" - shattered the air about their ears, shaking both their courage and their curiosity and they fled from the terrifying blast.

Cartier noted in his diary that they "would no more follow us." They did, however, for the next morning they reappeared with an obvious desire to trade. Cartier provided the first detailed description of the ceremonials surrounding trade when they returned on July 7th, "making signs to us that they had come to barter." Cartier had brought well-chosen trade goods: "knives and other iron goods and a red cap for their chief.". Before long the Natives were eagerly trading beautiful furs for tawdry trinkets from the first whitemen they had ever seen. The first day of the exchange was brief, the natives leaving stripped even of the furs on their backs.

On the shores of the Bay of Chaleur the Indians were probably Micmacs. The Indians whom Cartier met further north in Gaspe Basin were a migrant tribe of the Iroquois who had come from a distant region near Quebec to fish and take seals. Later Cartier encountered Iroquoians cultivating land and controlling the country around present-day Montreal. Before long Cartier realized that these North American people were not all alike: they spoke different languages, practised contrasting lifestyles and warred against each other.

There are, it may be said, many kinds of voices in the world and none of them is without signification. Therefore, if I know not the meaning of the voice, I shall be unto him that speaketh a barbarian. And he that speaketh shall be a barbarian to me. 1st Corinthians 14, 10-11.

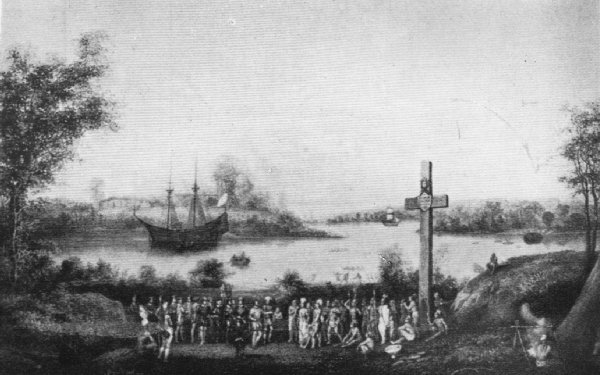

The next day Cartier turned north again and came to another deep bay which he hoped would lead to the illusive Cathay. Here on the mainland on Friday July 24th, 1534, Cartier claimed for France a sovereignty which endured for more than two hundred years. From the abundant timber at hand, he had construct a cross thirty feet high. To this he nailed a shield bearing the fleur de lis and over it in huge letters carved in wood he affixed the inscription Vive Le Roy De France. Here on land he named Gaspe Cartier had founded an empire for France. Great ceremony attended the event and the onlooking Indians realized instinctively that Cartier was claiming this land. After the French had withdrawn to their ships, the local chief paddled out with his brother and two sons to protest what had been done. After a long oration, he pointed shoreward to the cross and with hand signs attempted to make it understood that the country belonged to him and his people. Before long, however, he was pacified by gifts and other goodies including food and drink. Cartier resolved to carry some natives back to France with him and requested the chief's consent to take two of his sons back to France. After receiving shirts, red caps and other clothing, they readily agreed to accompany him. The next day the ships weighed anchor, their departure accompanied by boatloads of shouting, waving Natives. Despite being tossed about by tempests, they finally had fair weather "and upon the 5th of September in the said year we came to the port of St. Malo whence we departed."

|

|

Possession in the name of Francois I |

|

|

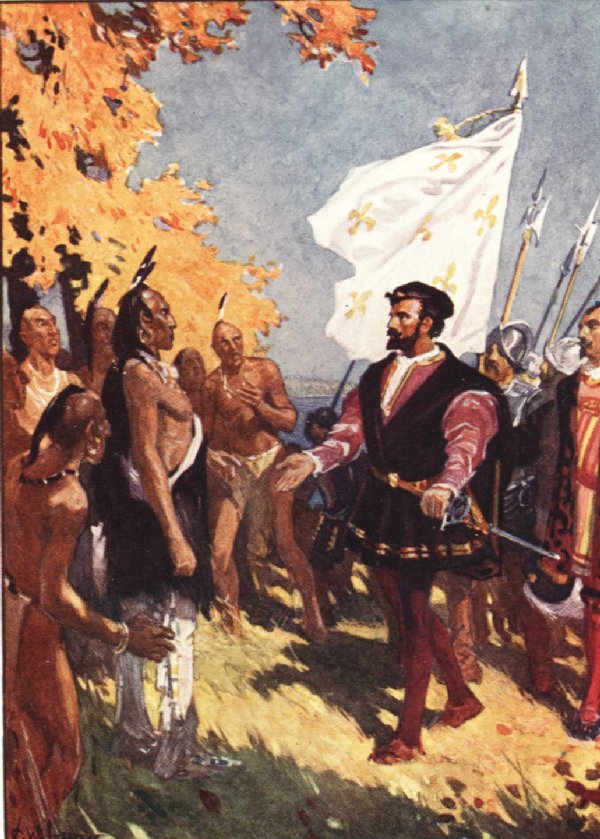

Cartier and The Aboriginals |

In May, 1535 Cartier set forth on his second and most important expedition to the new world, hoping to find the Great Lakes and the elusive route to China. By the middle of May the ships were manned and provisioned waiting only a fair wind to sail. They were three in number - the Grand Hermine of 120 tons, the Petite Hermine of 60 tons and a small vessel of 40 tons known as Emerillon. The company numbered in all one 120 persons including the two Aboriginal boys who would now serve as guides. With their help, Cartier "found the way to the mouth of the great river of Hochelega and the route toward Canada." On September 1 he reached the mouth of the Saguenay and anchored probably in the little bay where Tadoussac stands. As he sailed up the great St. Lawrence River his first impression of this new continent was of its vastness and silence. The land lay tranquilly at rest, waiting in for the arrival of man to waken it to fruitfulness. The forests along its shores were tall, dense, interminable and inscrutable. The only sounds issuing from the daunting denseness the occasional splash of a leaping fish and the distant cawing of a crow from the treetops.

|

|

1541: Cartier's Three Ships Grand Heremine, Petite Hermine, & Emerillon |

On the 8th he arrived at the Indian village of Stadacona standing in the shadow of the great rock of Quebec. "On the morrow the lord of Canada named Donnacona came to our ships accompanied by many Indians in twelve canoes." When he came up to the captain's vessel on board which were Taignoagny and Domagaya, the two Native boys who had accompanied Cartier to France. They spoke to the chief and told him what they had seen in France and that they had been well treated, at which the chief expressed much pleasure. Later Cartier visited with Chief Donnacona at his village Stadacona (now Quebec City) lying at a point where the mighty river St. Lawrance narrows to the breadth of a mile. Donnacona attempted to dissuade Cartier from proceeding on up the river for he was reluctant to share the French and their fortunes with Indians resident upriver. Once during his conversation with Cartier, "all his people at once in a loud voice cast out three great cries together in full voice, a sound horrible to hear." It was the Indian war whoop which in days to come would curdle the blood of many in New France. Cartier declared that his king had ordered him to go and Donnacona relucantly acquiesced.

|

|

Cartier at Hochelega |

Taking no Natives with him as guides, Cartier left in the Emerillon on the 19th of September to discover the elusive China. The journey west to Hochelega (now Montreal) took thirteen days. The glowing autumn colours delighted the French who recorded they observed "the finest trees in the world" including oaks, elms, pines, cedars and birches. Rapids in the St.Lawrence which Cartier named La Chine (China) prevented his journey by ship further up the river, so he left it well guarded and continued in longboats. Finally they reached open fields with a great mountain looming up behind. This highest point along that part of the St. Lawrence was called Hochelega by the Natives. It was not the sought after city of the East. They were greeted by hundreds of natives demonstrating with wonder and delight. The town was enclosed and fortified as oonstructed by the Iroquois, "compassed round about with timber, with three courses of rampires, one within another, framed like sharp spikes."

Cartier and his men climbed the mountain and when they reached the top they beheld so impressive a panorama that Cartier gave the mountain the name Mount Royal.In all directions were mountains . He described the landscape that opened before them. "On reaching the summit we had a view of the land for more than thiry leagues round about. Towards the north there is a range of mountains running east and west. And another range to the south. Between these ranges there lies a great plain, the fairest land it is possible to see, being arable, level and flat. And in the midst of this flat region flowed the mighty river extending beyond the spot where we had left our longboats. There is the most violent rapid it is possible to see which we were unable to pass. As far as the eye can see, one sees the river, grand, broad and extensive which came from the southwest and flowed near three fine conical mountains which we estimated to be some fifteen leagues away." Cartier gazed at the silver ribbon stretching to the west until it was lost in the distance. The violent rapids were named by Cartier in mockery La Chine (China). The sight of them removed any last hopes of voyaging by boat directly to the great cities of China. Like Moses from Mount Nebo, Cartier stared westward to the promised land upon which he would never tread. Cartier could go no further. The Lachine Rapids flooding downward at a speed of thirty miles an hour and more barred passage by the ship's boats. Cartier spent the winter in Stadaconna during which time he studied the life of the Natives. Cartier provided this description of the Stadacona Indians' use of tobacco.

"There groweth a certain kind of herb whereof in summer they make a great provision for all the year. They wear it about their necks wrapped in a little beast's skin made like a little bag with a hollow piece of wood or stone. At frequent intervals they crumble up this plant into powder, which they place in one of the large openings of the hollow instrument and laying a live coal on top suck at the other end to such an extent that they fill their bodies so full of smoke that it streams out of their mouths and nostrils as from a chimney. They say it keeps them warm and in good health and never go about without these things. We made a trial of this smoke. When it is in one's mouth one would think one had taken powdered pepper it was so hot." This was probably the white man's first experiment with tobacco and it occurred some fifty years before Sir Walter Raleigh began to popularize smoking in Queen Elizabeth's London.

During the winter many of Cartier's crew died from scurvy. Finally, after questioning Domagaya, Cartier learned the secret of the remedy: a drink made from white cedar. The crew was quickly cured.Cartier returned home on May 6th, 1536 and it was five years before King Francis I turned his attention once again to these new lands. At the head of this third voyage the king placed Sieur de Roberval whom he created viceroy and lieutenant-general of Canada. Cartier was to accompany Roberval in the capacity of captain-general and master-pilot. The crew members were recruited from the prisons. The lure was now the Kingdom of Saguenay which it was fondly believed would rival the wealth of the Spanish empire. Cartier was ready to leave in May 1541 but Roberval was not, so he authorized Cartier to proceed ahead on his own. which he did with five ships. Cartier returned to Stadaconna, learned that Donnacona had died and discovered that relations between the French and the Iroquois had deteriorated. The narrative of the great explorer closed with the following rather ominous comments. "And when we arrived at our fort, we understood by our people that the savages of the country came not any more about our fort, and that they were in a great doubt and fear of us. Wherefore our captain, having been advised by some of our men who had been as Stadacona to visit them, that there was a great number of the country people assembled together, caused all things in our fortress to be set in good order." [that is, they prepared for any eventuality] Fearing for their lives Cartier and company departed in June 1542 and returned to France.

The French crown sponsored the voyages of Jacques Cartier (1534,1535-1536, 1541-1542) in an attempt to find the Spice Islands of Southeast Asia, but apart from establishing French claim to important parts of what is today Canada, these trips achieved little. The settlements founded by Cartier and later Roberval in 1541-1543 failed because they lacked an economic foundation and because the Native population was hostile to them.

Nevertheless, Cartier did add materially to what was known about the new land. Not satisfied to sail up and down the Atlantic coast, he penetrated bodly into the St. Lawrence exploring it to Montreal. Cartier's achievements were the beginning of far-reaching work, the competion of which fell into other hands. He came to these coasts to find a pathway to the empire of the East and found instead a country vast and beautiful beyond his dreams. He discovered Canada.It was oftimes the custom of officials of the port of St. Malo to record the death of any townsman of note. In the margins of documents dated September 1, 1557, there is written in the penmanship of the time: "This Wednesday about five in the morning died Jacques Cartier."

It might be argued that a prolific little animal was the real founder of Canada. Without the beaver the country's settlement and development would, perhaps, have been merely an extension of the English colonies. Male fashions in clothing also played a signifcant part - witd brimmed hats made of fur felt were highly prized and beaver fur made the best felt. Trade between Natives and Europeans took on new dimensions with the gradual development of the European market for furs, particularly beaver. It was by far the most important animal fur in Canadian history. The long barbs at the tip of each hair in the beaver's soft underpelt made it ideal for felt. The felt-making technique transformed animal fur into a soft, supple, water-resistant material. The supply of North American beaver stimulated European felt production and brought wide-brimmed hats into fashion. By the 1630s it was standard military dress and it had reached all classes of society.

|

|

Castor canadensis - North American Beaver |

The fur trade depended on the labour of Native peoples and on their centuries-old trading netwaork. Each hunting Native family used some thirty beaver annually for food and robes. After being worn for a year, the pelts that made up the robes shed their long, outer guard hairs, exposing the short hairs required for the pelting process. Several hundred thousand pelts, known as castor gras d'hiver were availabel annually in the St. Lawrence- great Lakes regions at the end of the sixteenth century. They were in great demand by Europeans.Fur became the second staple of the Canadian economy. The fur trade led to the exploration of the Great Lakes and contributed to the war between France and Britain.

From time to time it has been suggested by various federal government ministers, that the Indian Act should be eliminated in order to dismantle the "custodial bureaucracy" which for over a century has bound the First Nations peoples in a maze of regulations. Although the Assembly of First Nations Chiefs once agreed that the time had come for the demise of the Department of Indian Affairs, some Aboriginals oppose this for fear there could be a high cost to cutting these historic ties with Ottawa.

This dilemma remains largely unchanged from that articulated over two hundred years ago by Joseph Brant, the illustrious chief of the Six Nations, when he wrote that the Aboriginals

In His Own Words"must be convinced that change will not place them in a worse situation than they are in now. Change must occur accordance with strict adherence to the dictates of Justice and rigid observance of all compacts and engagements on the part of the white people, including fixed boundaries and territories described."

|

|

Joseph Brant, Chief of the Six Nations |

Brant wisely warned his people that they must foster "unity and concord among themselves" and encourage rather than discourage their own customs.

The origins of the Department of Indian Affairs can be traced to the days when our country was a colony and competition was intense to entice Aboriginals to become involved in the white man's wars. Britain was successful in securing an alliance with Native warriors, first against the French and later against the Americans. British officials challenged the Six Nations' sachems "to join us in our fight against the Bostonians." And they did.

Aboriginal affairs took on a new importance following the conquest of Canada. Previously, matters pertaining to the Natives had been handled in a makeshift manner, with disorganized, piecemeal record-keeping and no consistent, coherent policy. Now Indian Affairs began to be managed on a broader, more systematic basis. As frontiersmen and fur traders made their way westward, Pontiac's rebellion burst into flames in 1763, and as a result a more carefully considered plan became imperative. It was decided to keep settlers from going beyond the mountains until Aboriginal land titles could be extinguished.

A plan was designed in 1764 by which two Superintendents-General of Indian Affairs were appointed, both answerable directly to the Imperial government. [the name of the British government when it dealt with colonial affairs] Under their overall direction, various assistant superintendents and commissaries acted as go-betweens the whites and the Natives, administered law in the back country and in particular secured treaties for Native land titles.

As Superintendent of Indian Affairs, Sir John and Sir William Johnson were responsible for establishing a number of policies in this regard. Various of these policies became rooted in colonial law and eventually found their way into the Indian Act. The earliest legislation in this regard was directed largely at regulating trade with Natives and overseeing the sale of their lands. The Johnson frequently conferred with the Aboriginal sachems, settling grievances and renewing covenants of friendship with them on behalf of the Crown.

|

|

Sir John Johnson |

Some believe that the Indian Affairs bureaucracy began to be built at Fort Niagara on the banks of the Niagara River, the chief British point of contact with the Iroquois. The fort had been surrendered by the French to Johnson and a party of Native warriors in 1759. At the commencement of British-American hostilities in 1776, the nearest Aboriginal encampment was 80 miles from the fort. As the revolutionary war intensified, Britain's Native allies drew closer to the British base of operations until some two thousand had gathered in the vicinity of the fort.

The lands of the Six Nations originally extended roughly from Lake Ontario south to the Susquehanna River with the New York's Catskill Mountains closing in on the east and Lake Erie bordering on the west. Washington marked their settlements down for destruction, and in 1779 following a two-pronged American attack on Iroquois settlements in upper New York, five thousand Natives sought refuge near Niagara. They remained there until the end of the war, launching lightning raids from the fort to points all along the New York and Pennsylvania frontiers.

The Aboriginals were a free and independent people, subject neither to subordination nor domination. The cost of the conflict to them was high in lives and land lost, and as important allies of Britain they expected compensation. The compensation outlay rose rapidly over a short period of time with the quantity of provisions and presents increasing from 500 pounds at the commencement of the war in 1776 to 100,000 pounds by 1781. The expenditures required to provision the Natives at the three upper forts of Niagara, Detroit and Michilimackinac reportedly exceeded the cost of the whole British military establishment in Canada, exclusive of provisions.

It was feared the Americans might attempt to seize the western posts, and Lord Dorchester was instructed to recapture them if this did occur. If the posts were to remain in British hands, friendship with the Native peoples was critically important, for possession of the posts made possible control of the fur trade and defence of the colony. As a result the quantity of goods provided for the Native peoples was increased and Lord Dorchester was instructed to supply them with such "ammunition as might enable them to defend themselves" against the Americans. These supplies were funneled through the Indian Department and merchants who furnished them throughout the revolution became very wealthy. Among the goods distributed at Fort Niagara in 1781 were 12 thousand blankets, 23,500 yards of cloth; 5 thousand silver ear bobs; 75 dozen razors and 20 gross of Jew's harps. Although many of these items came from Britain, a large number were provided by local suppliers. This made provisioning of the Indian department a prized contract for area merchants.

|

|

Lord Dorchester |

To compensate its faithful Iroquois allies for the land they lost when Britain signed the peace treaty with the Americans, the British provided the Six Nations' people with land along the Bay of Quinte and a large grant of land west of Lake Ontario along the Grand River[shaded below], which was purchased by the British government from the Mississaugas for the Six Nations people. Their needs were given every consideration and when other parts of the province had little in the way of schools and churches, the Six Nations along the Grand River were supplied with both. Their church was adorned with crimson pulpit furniture and a service of solid silver was the personal gift of Queen Anne.

|

|

Grand River Grant (6miles on each side of the Grand River from its mouth on Lake Erid to its origin in the north) |

Britain hoped that with her help,the confederate tribes of the northwest would be able to resist the advance of American settlers into the land south of the Great Lakes. Ideally a Native buffer state here would separate the British colonies and the American settlements. Lord Dorchester warned Aboriginal sachems in 1794 that unless a line were drawn by them, the encroachment of Americans on their land as Yankee settlers forged ever-further into 'Indian territory' would ultimately mean that a line would have to be "drawn by the Warriors' children."

Governor Simcoe used all his diplomatic skills to convince these "firm friends of the British" that it was in their best interests to remain loyal to the king. Britain's alliance with the Aboriginals was maintained with supplies and other presents, including the customary practice of "distinguishing the Chiefs by a Private Donation." The provision of presents recognized the sacredness of treaty promises. Whatever was once written down and signed by sovereign and the sachem would bind the parties for as long as the "sun shines and the rivers flow. " Like the rainbow the treaties would beam unbroken and the Natives pledged their word to this by delivery a Wampum Belt of Shells.

The Indian Department became a quasi-military institution created to cater to the needs of Britain's vital allies. A critical function of its agents was to maintain the "union of the Indian Nations and exert all influence to encourage and cement the same." A strong union of the Native Nations was all important.

The Indian Department became increasingly active following the Chesapeake Affair in 1807. British pursuit of deserters on the American frigate, Chesapeake, resulted in a number of men being killed and wounded.American anger at this arbitrary assault almost catapulted the country into war.This threat of conflict quickly revived the British-Aboriginal alliance. Passions were inflamed as Native braves were regularly reminded of the loss of their land to the artful Americans. While braves were cautioned against any unilateral acts of aggression against the Americans, it was clearly understood that if Native aid was needed by the British, warriors would be ready. At the time, British plans for the braves was defensive not offensive.

The Indian Affairs department's traditions were set by Sir William Johnson and carried on by the Department's dedicated members like William Claus, deputy superintendent of the Six Nations at Fort George. During the war of 1812, Claus was named colonel of the 1st Lincoln Militia and in that capacity he met regularly in council with Natives at Fort George. Before 1830 the central function of the Indian Department in British North America was to provide presents as signs of friendship and alliance. The origin of providing presents is unclear, but they had been paid before the American War of Independence and became even more important as a result of this conflict.

|

|

Sir Wm Johnson & Colonel Wm Claus |

|

|

Sir Guy Johnson, successor to Wm Johnson, as Superintendent of Northern Indian Affairs |

Guy was an able and tireless administrator who did much to keep the Iroquois loyal to the British cause during the American Revolution.

The necessity of keeping Aboriginal allies in strong bonds of friendship made the annual giving of presents a vital aspect of British military policy. Agents were appointed exclusively for this purpose and funds were provided directly from Imperial parliamentary grants. The military necessity for these presents continued until after the War of 1812.By the end of 1820 it was becoming clear that the Natives' role as allies was becoming less important and a new policy was implemented whose purpose was "to civilize and Christianize" the Natives and convince them to settle down and take up farming.

The new priority was to buy up Native land and free it for occupancy by whites as it became clear that the Natives were impeding settlement in Upper Canada. The sale price of the land was to be used to sustain the tribes who were to be relocated to tracts of land known as 'reserves.' The land agreements contained clauses such as "the proceeds of the land surrendered shall be applied towards educating your children and instructing yourselves in the principles of the Christian religion with certain portions of the said tract set apart for your accommodation and that of your families on which homes will be erected as soon as possible."

The Indian department became responsible for overseeing the sale of Aboriginal lands, collecting and investing the monies therefrom and administering these funds until the Native peoples were taught to assume this responsibility themselves and so eliminate the necessity for the department. The Indian Department changed from a military to a maintenance function, as its members fought for adequate funding to assist the Aboriginals to adapt to a new way of life.

Copyright © 2004 W. R. Wilson