foreword | Historical Narratives | Resources | Links | Contact

1ST BURIAL IN BROCK'S BASTION

"History is romance and tragedy."

Brock galloped along the muddy road to Queenston, his cloak flaring in the northeast wind.

|

Mud-spattered Brock’s first act on reaching Queenston was to order the light company of the 49th down from the Heights into the village to support the hard-pressed grenadier company attempting to throw back the invaders . He had little reason to suspect that in the early morning hours an enemy party of regulars led by Captain Wool would mount the steep path and make its way to the top. Urging Alfred up the slope to the 18-pounder bombarding the attackers, Brock dismounted to get a better view of the situation. This was no mere feint. Across the river massing Americans awaited their turn to cross in the boats ferrying fighters to the Canadian shore. Suddenly a battle cry came from the crest of the Heights and American regulars with Wool in the lead charged down on the redan. Taking time only to spike the touch hole of the cannon, the redcoats with Brock leading his mount fled down the slope to the village.

Brock was determined to capture the cannon located in a commanding position and with raised sword to rally the hundred or so men of the 49th, he started up the slippery slope in the face of heavy musket fire from soldiers shooting from behind trees and logs. Resplendent in his cocked hat, white breeches, gold-trimmed, scarlet coat [*] with the sash he received from Tecumseh, he was instantly recognizable as a person of some importance.

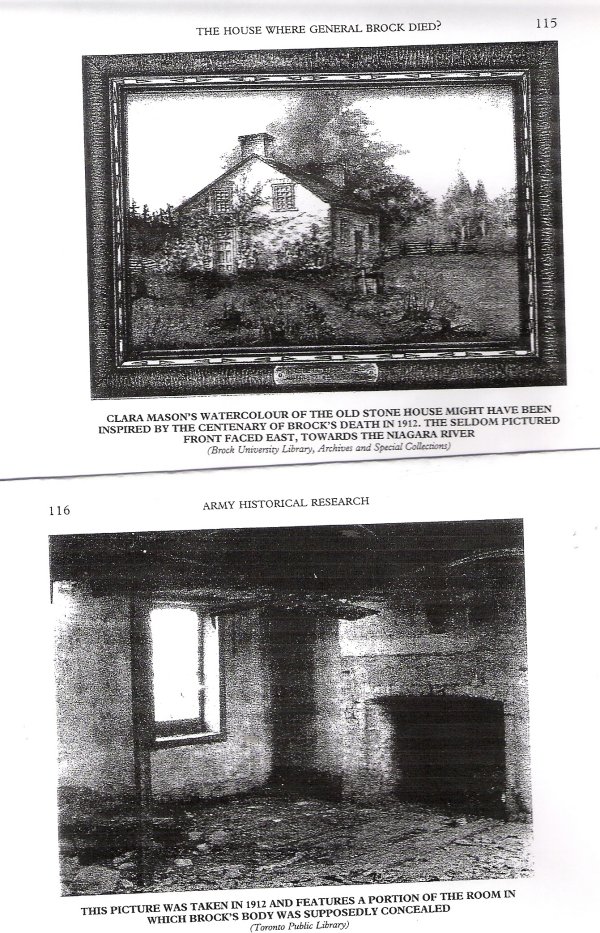

.An American sharpshooter named Robert Walcot stepped to the edge of the hill, took careful aim at the towering figure and squeezed the trigger. His shot struck Brock on the left side of his chest. Brock fell on his left side within a few feet of a distraught soldier who frantically inquired, "Are you much hurt, Sir?" Brock placed his hand on his chest, but made no reply.[**] He expired almost immediately, his death occurring one week after his forty-third birthday. Brock's body carried by his Aide-de-Camp, Glegg, to Patrick McCabe's Stone House in Queenston.

|

The top painting is from Brock University Library, Archives and Special Collections. The bottom photo is from the Toronto Public Library.

John Macdonell, a lieutenant-colonel in Upper Canada's militia and Brock's 27-year old provincial aide-de-camp, departed from Fort George right after Brock. In his haste to overtake his commander, Macdonell, who was also the province's attorney general, left without his sword. En route he met an officer named Jarvis and borrowed his sword and told Jarvis to fetch the sword he had left in his quarters at Fort George. On reaching the heights, he heard of his commander's death and immediately led a charge of his own with a detachment of York militia and some 49th of Foot. It was thrown back and Macdonell badly wounded. In the words of a friend who was present, "Macdonell was mounted and animating his men to charge." He was wounded in three or four places, fell to the ground and was trampled by his horse. Writhing in pain for the rest of the day, he finally died shortly after midnight.

Some thought Macdonell's charge fine but foolhardy. Brock's other aide-de-camp, Major John Glegg of the 49th Regiment, observed that Macdonell "appeared determined to accompany Brock to the regions of eternal bliss." In so doing he became with Brock part of the lore of the War of 1812.

Thanks largely to the incapacity of American leadership and the militia's fear of the Aboriginal warriors whose savage cries carried across the river, the Americans failed to follow up on their success on the heights. Their indecision gave time for Sheaffe to arrive from Fort George with reinforcements. In the afternoon of the same day, Sheaffe's well led forces imposed a crushing and costly defeat on the invaders.

In sad and solemn silence Brock's remains were conveyed from Queenston to Government House at Niagara, where the body, "bedewed with the tears of many affectionate friends," was laid in state. It was decided that Macdonell would be buried with his chief and that Glegg would handle the arrangements.

The burial of Brock and Macdonell took place at 10:00 a.m. on the sixteenth of October, a day of mourning in Niagara. Its streets were crowded as never before with people from all parts of the province - men, women and children in mourning clothes and tears. The troops, regulars and militia, formed with reverse arms on the street opposite Government House and all flags were at half-mast. The mournful strains of the Dead March filled the air with sadness as the procession moved off towards Fort George. Mindful of Brock's aversion to ostentatious display, Major Glegg endeavoured to plan the sorrowful ceremony with "native simplicity" while observing the military honours that could not be avoided. An onlooker described the event as "the grandest and most solemn burial ever I witnessed."

Glegg has left this description of the funeral.

In His Own Words

"No pen can describe the real scenes of that mournful day. A more solemn and affecting spectacle was, perhaps, never witnessed. As every arrangement connected with that affecting ceremony fell to my lot, a second attack being expected hourly and the minds of all being fully occupied with other duties of their respective stations, I anxiously endeavoured to perform this last tribute of affection in a manner corresponding with the elevated virtues of my departed patron. Considering that an interment in every respect military would be the most appropriate to the character of our dear friend, I chose the northeast bastion [***] in Fort George."

It is interesting to note that while Glegg was fullsome in his praise of Brock, another colleague, Brock's Brigade Major Thomas Evans saw things differently. While mindful of Brock's military brilliance, Evans was critical of "his high spirit which would never descend to particulars and as a result under his command details which were none the less essential were neglected." Brock, it seems, was not a man for minor matters.

Brock and Macdonell were interred on 16 October 1812 at the north-east cavalier bastion [See Diagram Below] located at northern-most corner of Fort George. Known as the York Bastion, it was constructed at Brock's orders and had just been finished under his daily superintendence.

The distance between Government House and the garrison was lined with a double row of Indians, and militia men and resting on their arms reversed. The caskets were lowered into a single grave.

The funeral procession designed to the last trumpet was as follows.

The FORT'S Major Campbell

Sixty men of the 41st Regiment commanded by a subaltern.

Sixty members of the Militia commanded by a captain.

Two six-pounders firing minute guns.

Band of the 41st Regiment

The Remaining corps and detachments of the Garrison with about 200 Natives in reserve order forming a path through which the procession passed extending from the Government House to the Garrison.

The Regimental Band of the 41st Regiment

Drums covered with black cloth and muffled.

The Late General's horse, Alfred, [****] was fully caparisoned and led by four grooms.

Servants of the General

Military Surgeons

THE REVEREND MR. Robert ADDISON[*****]

The body of Lieutenant Colonel John Macdonell

Various Military Officers

Chief Mourner - Mr. Macdonell

The Body of Major General Brock

Various Aides-de-Camp of the 41st and 49th Regiments

Chief Mourners

Major General Sheaffe & Lieutenant Colonel Meyers

The Civil Staff

Friends of the Deceased

Inhabitants

All officers wore crepe on their left arm and on their sword knots. Officers throughout the province wore crepe on the left arm for one month. At the suggestion of Colonel Winfield Scott, the American military at Fort Niagara paid a touching tribute to the memory of their fallen foe and fired minute guns as well "as a mark of respect to a brave enemy.".

On the 6th of November, 1812, Aboriginal warriors met at the Council House where they too bemoaned the death of Brock. The references made to the beloved general were most poignant. There were present representatives of the Six Nations, Hurons, Chippewas, and Pottawattomies, as well as Colonel William Claus. Deputy Superintendent-General, Captain Norton, Captain J. B. Rousseaux, and several other officers of the Indian Department. Little Cayuga was the chief speaker.

In His Own Words"Brothers, we, therefore, now seeing you darkened with grief, your eyes dim with tears and your throats stopped with the force of your affection, with these strings of wampum we wipe away your tears that you may see clearly the surrounding objects, we clear the passage in your throats that you may have free utterance for your thoughts, and we wipe clear from blood the place of your abode, that you may sit there in comfort without having renewed the remembrance of your loss by the remaining stains of blood. That the remains of your late beloved friend and commander, General Brock, shall receive no injury, we cover it with this belt of wampum, which we do from the grateful sensations which his friendship towards us inspired us with, also in conformity to the custom of our ancestors."

With the address were presented eight strings of white wampum and a large white belt: and five strings of white wampum were placed over his grave that it might receive no injury.

[*] The jacket, a well-used one which he wore while a brigadier general, is on display at the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa. The bullet hole is below the lapel and midway between the second set of buttons. The pellet did not penetrate the back of the coat.]

[**] The last words of dying heroes are always the subject of debate. While some accounts indicate Brock died without uttering a word, Glegg's letter suggests otherwise. Some versions state Brock's dying words were " Push on brave York volunteers." Other reports indicate he shouted this as he galloped south to the scene of the American attack.

|

[***] Bastion: A projecting part of a fortification consisting of four sides (two faces and two flanks) allowing the defenders' fire to cover the main walls of the fort.

[****] Alfred, a ten year old stallion, had been a gift from Sir James Craig to Brock, given, said Craig, because Brock was "a kind and careful master." A memorial to Alfred is located near the spot where Brock fell. It states that the horse was killed along with its rider, John Macdonell who mounted it following Brock's death. The description above of the first funeral indicates otherwise for according to it the horse was very much alive.

[*****]Living History

The Reverend George Addison, currently chaplain at Brock University, is a direct descendant of William Addison, brother of the Reverend Robert Addison, Major General Isaac Brock's Chaplain and clergyman who officiated at the funeral of Isaac Brock in 1812.

Sally Greenaway the 4th Great-grand niece of Sir Isaac Brock met George Addison, the 4th Great-grand nephew of Robert Addison, on July 31st, 2006 when Sally visited the area to view the sites associated with her illustrious ancestor which included a tour of Brock University. Sally Greenaway is the direct descendant of Savery Brock, Isaac Brock's brother.

|

|

Sally Greenaway and Reverend George Addison |

Copyright © 2013 Website Administrator